Abstract

Among the determinants of economic freedom, the presence of different ethnic groups within a country has sometimes been explored by the empirical literature, without conclusive evidence on the sign of the relation, its drivers, and the conditions under which it holds. This paper offers new evidence by empirically modelling how ethnic fragmentation is related to economic freedom, as measured by the Economic Freedom Index and by each of its numerous areas, components and sub-components. The results provide insights on the components driving the effect and, interestingly, detect notable differences between developed and developing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The role of institutions in promoting economic growth is a major field of study for economists since the second half of the twentieth century (North, 1990; Rodrik, 2007). Indices of economic freedom represent a widely accepted way to measure the quality of the institutions that are relevant for economic growth (Gwartney, 2009; Williamson and Mathers, 2011), at least if we assume a liberal view of economics and the functioning of economies. Yet, institutions are not exogenous, as they depend on the decisions and policies enacted by the national (and sometimes international) governing bodies. Such bodies are not independent of the internal situations of the countries that they rule: as Reilly (2000) highlights, one of the major factors that affect policies is the presence of different ethnic groups within a country. Indeed, these typically claim the right to protection for their cultural traits and representation in elected bodies; in some cases, ethnic differences result in tensions and conflicts, so hampering economic activity (Alesina and La Ferrara, 2005). As a consequence, institutions, as measured by economic freedom indices, may also mediate the effect of ethnic diversity on economic growth; in this regard, the present study aims at inquiring into the effects that ethnic fragmentation has on economic freedom and its different areas, components and sub-components.

Literature exists on the relationship between ethnic fragmentation and economic freedom. However, as the next section will show in more detail, there is no conclusive evidence about how ethnic fragmentation affects economic freedom: some scholars find positive influence, while others show the opposite. Moreover, all the existing indices of economic freedom are composite measures of various institutional dimensions, as they result from aggregations of sub- and sub-sub-indices that assess the quality of different institutional aspects. While among these aspects multiple correlations generally exist, they may be only partial and, in some cases, they may take opposite signs. The extant literature has then analyzed the relationship between ethnic fragmentation and single components of the aggregated indices of economic freedom, again finding mixed evidence. Few studies, conversely, have inquired into the effect of ethnic fragmentation on a broader set of components (Heckelman and Wilson, 2018; Alhassan and Kilishi 2019; Soysa and Almas 2019; Murphy, 2015; Nikolaev and Salahodjaev, 2017). For example, Alhassan and Kilishi (2019) consider a sample of 43 Sub-Saharan countries and inquire how ethnic, linguistic and religious fragmentation affects economic freedom (they use the index calculated by the Heritage Foundation) and four of its components.Footnote 1 Analogously, Heckelman and Wilson (2018) estimate the impact of ethnic and linguistic fractionalization on five dimensions of economic freedom in a sample of 117 countries observed at six points in time between 1975 and 2002, while de Soysa and Almas (2019) analyze the effects of ethnic diversity on economic freedom and five subcomponents for 150 countries over 24 years (1991–2015). However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous work has adopted a more detailed approach to investigate the relationship between ethnic fragmentation and the full set of the numerous components and sub-components of economic freedom in a large sample of countries. The first novelty of the analysis presented here is therefore the level of detail. The empirical analysis indeed will show how ethnic fragmentation relates to economic freedom and all its many dimensions (measured by 50 different sub-indicators), as defined in the report Economic Freedom of the World, annually published by the Fraser Institute. The reason why this paper goes so in depth is to understand whether the effects detected (or not) on the global indices are driven by any particular components and sub-components.

The second novelty is that the analysis also presents and discusses the results separately for developed and developing countries. On the one hand, the stage of economic development may play a role, affecting the perception of ethnic divisions (Sundaram and Hui 2003). On the other hand, in most developing economies, ethnic differences are a characteristic of the country, as different ethnic groups were present when the postcolonial country was founded; instead, many developed countries are ethnically diversified more as a consequence of immigration waves than because various ethnic groups were already present. The dynamics that govern the relation between ethnic fractionalization and economic freedom can then differ between the two groups of countries. As some works suggest (see the next section), this difference may be crucial.

The main results of the analysis show that: (1) the effect of ethnic fragmentation on economic freedom differs according to the component of economic freedom considered; (2) such effect also differs between developed and developing countries. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a general review of the relevant literature on the potential positive and negative impacts of ethnic fractionalization on economic freedom, which will orient the interpretation of the results. Section 3 presents the methodology and data used in the empirical analysis. Section 4 reports and discusses the main findings, while the last section concludes.

2 Literature review

Economists have widely studied the relationship between ethnic fragmentation and growth. Alesina and La Ferrara (2005) present an extensive review of the literature, showing that ethnic fragmentation is generally found to reduce economic growth. In particular, the relationship between the two is mediated by the public policies adopted by governments, as ethnic fragmentation and divisions largely influence economic policies reducing their effectiveness and efficiency. Easterly and Levine (1997) identify political instability, distorted exchange rates, and high government deficits as major institutional drawbacks that lower economic growth and are explained by ethnic fragmentation. Analogously, Papyrakis and Mo (2014) find that ethnic fractionalization reduces economic growth, the most important transmission channel being represented by corruption. These results are consistent with those found by Mauro (1995), who shows that the efficiency of judicial systems correlates negatively with ethnolinguistic fragmentation; this in turn, increases political instability and corruption, thus hindering both the quality of institutions and the economic performance. The author concludes that ethnolinguistic fragmentation hampers economic growth through its effects on the aforementioned institutional variables. Alesina et al. (1999) provide further empirical evidence on the negative effects of ethnic fragmentation studying the provision of local public goods in the U.S.A. In general, the literature finds a negative correlation between ethnic fragmentation and the quality of government and economic governance (La Porta et al. 1999), and more recently, Churchill and Smyth (2017) show that ethnic diversity increases poverty, and thus reduces growth.

Further research refines the empirical evidence provided by the cited works, inquiring into the relationship between ethnic fragmentation and some institutional variables related to economic growth, showing that this last depends on the quality of institutions (North, 2002 and Acemoglu et al., 2005), which in turn requires appropriate policies, as good institutions are created by good policies (Glaeser et al., 2004).Footnote 2 Alonso and Garcimartín (2013) show that ethnic fragmentation reduces the quality of institutions through engendering more income inequality and less growth. Moreover, works exist that highlight the mediation effect of institutions between ethnic diversity and economic outcomes (Montalvo and Reynal-Querol, 2005 and Chadha and Nandwani, 2018). There are several institutions that favour growth, and there are many different ways to measure them (Woodruff, 2006 and Chong and Gradstein, 2007); one is represented by the various existing indices of economic freedom (Hall and Lawson, 2014), which aim at summarizing the quality of the institutions that are relevant for growth in a liberal perspective. The concept of economic freedom is of particular importance in institutional approaches, and many articles and books have appeared on it, showing that economic freedom fosters growth (Gwartney et al., 1999; Berggren, 2003; Gwartney, 2009 and Hall and Lawson, 2014), political freedom (Friedman, 1982)Footnote 3 and happiness (Hall and Lawson, 2014). In particular, the several components of economic freedom (Gwartney et al., 2005) may guide the choices of policy-makers. Moreover, given the evidence on the relationship between ethnic diversity and economic growth, and the suggestions that this effect is not direct, but mediated by institutional factors (Glaeser et al., 2004 and, more recently, Karnane and Quinn, 2019), investigating the impact of ethnic fragmentation on economic freedom seems relevant.

As mentioned above, the indices of economic freedom are comprehensive measures, which include several indicators of different institutional aspects affecting the structure of an economy. Several different indices were proposed over time; however, de Haan and Sturm (2000) suggest that they measure almost the same phenomenon and are therefore almost equivalent to each other. The domains of such indices represent the soundness of the legal framework and the level and quality of regulation of economic activities,Footnote 4 the weight of governmental interventions in the economy, the freedom to trade internationally and the money soundness.Footnote 5 Ethnic fragmentation may affect some of these institutional variables, and thus the composite index, as the political instability due to ethnic fragmentation may hinder, for instance, the protection of property rights (Svensson, 1998 and Busse and Hefeker, 2007). More generally, Polidano (2000), Alesina et al. (2011) and Root (2018) show that ethnolinguistic fractionalization may decrease the level of economic freedom by worsening, in particular, government effectiveness and the quality of regulation. More recently, Lawson et al. (2020) present a survey of the literature on factors that affect economic freedom: the authors confirm that, in general, articles present evidence on ethnic diversity as a factor reducing economic freedom. Faria et al. (2016) claim instead that genetic diversities are associated with an increase in economic freedom up to a certain point, after which they have an opposite effect.

Further empirical evidence shows that ethnic fragmentation worsens the rule of law and the protection of property rights (Baggio and Papyrakis 2010). Moreover, Glaeser and Saks (2006), Papyriakis and Mo (2014) and de Soysa and Almas (2019) highlight that ethnic diversity is generally associated with high levels of corruption. Papyriakis and Mo (2014), in particular, shows that the results do not change qualitatively if an index of either ethnic polarization or fractionalization is used.

Other components of the index of economic freedom may be negatively affected by ethnic fragmentation. Although in presence of high ethnic fractionalization governments tend to provide less public goods (Alesina et al., 1999) and transfers (Alesina et al., 2003 and Alesina and Glaeser, 2004), Annett (2001) shows that where ethnic diversity leads to conflicts, governments may increase public expenditure with the aim of appeasing oppositions and tensions. The author also shows that such policies are, on average, successful, with positive effects on growth. The evidence is however inconclusive, as opposite tendencies are at work, and it is not clear which prevails (Stichnoth and Van der Staeten, 2013). Considering instead international trade, Mohr and Shoobridge (2011) hypothesize that firms with ethnically diversified workforce are more able to trade internationally, as they have more experience with different tastes and preferences. Empirical analyses seem to provide ground for this hypothesis (Parrotta et al., 2016).

The evidence on the negative influence of ethnic fragmentation on economic freedom is however challengeable. Sunde et al. (2008) use countries whose mean absolute latitude is smaller than 23.5 degreesFootnote 6 to inquire into the effects of ethnic fragmentation on the quality of the rule of law and show that ethnic fragmentation has almost no effect on this component of economic freedom. Similarly, investigating convergence in economic freedom, Hall (2016) finds no significant effects of ethnic fractionalization. Analyzing a sample of 117 countries between 1975 and 2012, Heckelman and Wilson (2018) find that ethnic and linguistic fragmentation boosts economic freedom in the most democratic countries. Analogously, using a number of different measures of ethnic diversity, de Soysa et al. (2011) notice that ethnic diversity promotes economic freedom through the reduction of power concentration and political dissent. The positive association between diversity and various components of economic freedom is confirmed also in de Soysa and Almas (2019), consistently with Masella (2013), who observes that high ethnic fragmentation reduces nationalist sentiments among small minorities. This may in turn reduce the level of social conflicts, thus leading to an environment that is favourable to growth and economic freedom. Considering Sub-Saharan Africa, between 1995 and 2017, Alhassan and Kilishi (2019) find that ethnic diversity increases aggregate economic freedom, although this result is not robust in all the analyses presented in their article and the effects on the single components of the index are not statistically significant. However, the authors claim that ethnic diversity may provide impetus to economic freedom, through the development of stronger institutions. Clark et al. (2015) show that the increase in ethnic fragmentation experienced by advanced economies as a consequence of immigration flows does not affect or—at most—slightly improves the quality of institutions such as protection of property rights and rule of law. In this case, ethnic diversity is “imported” rather being connatural to the country; therefore the differences between developed and developing countries may depend on the origin of ethnic fragmentation (Wright 2012). In addition, the empirical literature provides evidence that people’s support to economic liberal policies is, on average, negatively correlated with per-capita income in a sample of advanced countries (Migheli 2014), which are generally characterized by low levels of ethnic fragmentation. However, when the two largest emerging economies by population size are considered, the opposite seems to hold (Migheli 2010). This confirms the importance of treating developed and developing countries separately.

Finally, many authors use ethnic fractionalization as a control variable when modelling economic freedom or its individual components; however they find limited significance (Norton 2000; March et al. 2017) or contrasting results and do not address potential endogeneity of ethnic fractionalization, as they focus on other main explanatory variables, like democracy (Hall 2016), aid (Kilby, 2005; Heckelman and Knack, 2008; Young and Sheehan, 2014; Schlosky and Young, 2017), inequality (Murphy, 2015), and historical presence of infectious diseases (Nikolaev and Salahodjaev, 2017).

From the findings of extant literature, it is clear that ethnic fractionalization can have a number of potential negative and positive impacts on the overall degree of economic freedom and its different dimensions, the ultimate effect being thus uncertain. Such findings are synthesized in Table 1, which provides an outlook of the extant theoretical and empirical literature that can facilitate the interpretation of the empirical results presented in Sect. 4.

3 Data and methodology

The empirical analysis aims at testing whether a relation between economic freedom and ethnic fractionalization exists, considering an initial panel of 82 developing and developed countries observed between 2000 and 2013. Given the limitations of the existing data sources, the sample size and the time coverage depend on data availability. The analysis first pools all the countries together, and then splits them into developing (low- and middle-income) and developed (high-income) economies.Footnote 7 The list of countries is reported in the appendix (Table 9). As emerged from the literature review, the dynamics that relate economic freedom to ethnic fractionalization can indeed differ according to the level of development (Lawson et al. 2020), and, consequently, studying them separately may provide more insightful results.

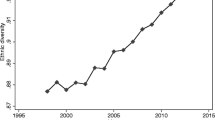

Economic freedom is measured through the index computed by the Fraser Institute, which monitors and surveys the level of economic freedom in the world through the publication of the report Economic Freedom of the World (EFW). The report was first presented in 1996 (Gwartney et al. 1996) and then published yearly since 2000 (Gwartney et al. 2019). According to the Institute, “economic freedom is present when economic activity is coordinated by personal choice, voluntary exchange, open markets, and clearly defined and enforced property rights. People are economically free when they are permitted to choose for themselves and engage in voluntary transactions as long as they do not harm the person or property of others” (Gwartney et al., 2016, p. 5).

The EFW Report provides a numerical assessment—between 0 and 10—of the degree of market liberalization in a country, where higher values represent greater economic freedom. Specifically, the index measures the degree of economic freedom calculated as the average of the scores obtained in five different areas, which are, in turn, average scores of relevant components and sub-components.Footnote 8 The definition of the five areas, based on Gwartney et al. 2019, is as follows. Size of government captures the size of government spending, taxation, and government-controlled enterprises in an economy. Legal system and property rights is about separation of powers and their proper functioning, and closely relates to the notion of rule of law. Sound money is mostly about inflation, which, according to the index proponents, affects the capacity of individuals to use economic freedom effectively by eroding the value of their wages and savings and introducing uncertainty about future values. Freedom to trade internationally covers freedom to trade and do business with firms and individuals in other nations and includes tariff and non-tariff trade barriers and controls to the movements of capital and people. Finally, regulation refers to regulation of the credit and labour markets and regulations of business activities. Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients between the aggregate index and each of its macro-components and the analogous coefficients calculated between the macro-components. Some correlations are small, and one is negative; the figures thus suggest that the exclusive use of the aggregated index may hide some of the effects of its components. Partial compensations of the effects, for instance, are possible because of the negative correlation between the size-of-government and the legal-system-and-property-rights areas.

The degree of ethnic fractionalization is retrieved from Drazanova (2019), whose work is based on the percentages of main ethnic groups provided by the CREG dataset (Nardulli et al. 2012).Footnote 9 The shares of country population by ethnic group (s) are calculated, cleaned, and aggregated by Drazanova (2019) to compute an index (EFR) corresponding to the probability that two randomly selected individuals from country i at time t are not from the same ethnic group. This index is given by the value of one minus a Herfindal-Hirshman index, also in line with Alesina et al. (2003):

The index is then used as an independent variable in regressions, where the dependent variable is the level of economic freedom; a series of control variables are also included in the specifications presented in this paper, so that the estimated equations take the following general form:

where i and t denote country and years respectively; EFIit is the level of economic freedom, alternatively measured by either the composite index of economic freedom or its single areas, components and sub-components; EFRit is the degree of ethnic fractionalization; XK,it is a vector of K control variables that the extant literature has found to affect the level of economic freedom; uit is the error term.

The selection of control variables is largely based on the studies reviewed by Lawson et al. (2020), who survey and discuss the main findings of the existing literature on the determinants of economic freedom. As countries with a higher level of democracy and political and human rights have been proven to be characterized by greater economic freedom, the set of control variables includes both aspects. The first is captured by a dummy variable representing the nature of the country regime, based on data from the Polity IV database, where regimes scoring from 6 to 10 are classified as democracies.Footnote 10 The level of political and human rights is taken from the Political Terror Scale dataset, described in detail in Wood and Gibney (2010), which provides measures of violation of physical integrity rights carried out by States or their agents.Footnote 11

Inequality is another factor that was proven to affect economic freedom, as high concentration of economic power fosters rent-seeking behaviors that preserve the status quo from the effects of liberal reforms (Alonso and Garcimartín 2013; Krieger and Meierrieks 2016; Lawson et al. 2020). Moreover, even if Lawson et al. (2020) show that the results of the extant literature are mixed, it seems that also the level of per capita income can affect the reform orientation of a country. Therefore, the real GDP per capita (from World Development Indicators—WDI) and the Gini index (from World Inequality Database—WID)Footnote 12 are included as regressors.

Finally, the amount of foreign aid that a country receives is an additional factor that can influence the level of economic freedom, especially when it is conditional on the implementation of political and institutional reforms (see Lawson et al. 2020, for a review of relevant literature). As developing countries are the main beneficiaries of development aid, the analysis controls for this effect through the amount of Net Official Development Assistance (ODA) as a percentage of GNI (source: WDI) limited to the sub-sample of developing economies. Further documentation on variables and data sources is available in Table 10, while Table 11 presents descriptive statistics (see Appendix).

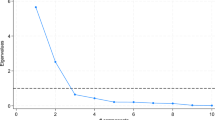

To perform a series of tests for identifying the most appropriate estimation model, Eq. 2 is estimated using country fixed-effects regressions to control for time-invariant country characteristics and taking the composite EFI as the dependent variable (Table 3, Columns 2, 5, 8, 11). The same estimates are also run using random-effect regressions (Table 3, Columns 1, 4, 7, 10), then a Hausman specification test (Hausman, 1978) is used to select the most efficient between the two estimators. After selecting it, the model is estimated again, using a two-stage least squares (2SLS) instrumental variables (IV) approach and treating ethnic fractionalization as endogenous, because of the potential reverse causality with economic freedom (Table 3, Columns 3, 6, 9, 12). Indeed, if the level of ethnic fractionalization can affect the degree of economic freedom, also the opposite may occur. In other words, the sense of membership to ethnic groups may be stronger when the absence of formal institutions is cause of insufficient provision of some goods and services (for example justice, protection of property rights, etc.), that conversely are provided by the ties between the members and the traditions of the group. For example, country institutions, such as a stronger legal system or a better protection of property rights, could substitute the informal institutions based on ethnicity, which in turn may partially lose their raison d’être (Ahlerup and Olsson 2012).

While under some circumstances the lagged levels of the explanatory variables can be taken as instruments (DeJong and Ripoll 2006; Reed 2015; Dithmer and Abdulai 2017), their large use in the recent literature has been highly debated (Bellemare et al. 2017), especially when the underlying process is persistent over time (Panizza and Presbitero 2014) and the lag length is short. This also limits their validity as internal instruments in the Generalized Method of Moments estimator (Arellano and Bond 1991) for linear dynamic panel data models (Panizza and Presbitero 2014).Footnote 13 The first best is then to find an alternative valid instrument. The political and economics literature provides several explanations for the level of ethnic diversity and fragmentation in a country (Alesina et al. 2003; Kaufmann 2011 and 2015; Ahlerup and Olsson 2012), among which geographical size, latitude, the date of country formation, founding date of the largest ethnic group, level of democracy and population density. As most of the mentioned variables are either time invariant or expected to be highly correlated with our dependent variable (like the level of democracy), population density as an instrument for ethnic fractionalization appears appropriate. Indeed, the geographic proximity with other people and cultures seems to affect ethnic diversity, fractionalization and identity. On the one hand, higher population density can lead people to conform (Wimmer et al. 2009; Kaufmann 2011; Ahlerup and Olsson 2012). On the other hand, under some circumstances (for example when resources are scarce), high population density can favour the rise of conflicts (Hauge and Ellingsen 1998; Acemoglu et al. 2019) which, in turn, reinforce social and ethnic identity (Sambanis and Shayo 2013). The relevance of the selected instrument is verified through the Anderson-Rubin-Wald test (Anderson and Rubin 1949), while the endogeneity of ethnic fractionalization is tested by means of Davidson and MacKinnon’s test of exogeneity (Davidson and MacKinnon 1993) and Hausman specification test (Hausman 1978). Such tests led to the selection of the most appropriate estimation method.

The exclusive use of population density as an instrument for ethnic fractionalization can nonetheless be questionable, so that testing the robustness of the results to the adoption of alternative strategies seems necessary. One could indeed argue that population density may sometimes be a rough proxy for the level of industrialization and structural change, which in turn can directly correlate with the degree of economic freedom, thus violating the exclusion restriction. To minimize the potential correlation of population density with the error term, its 40-year lagged value is used as an alternative instrument to its current values.Footnote 14 Moreover, the robustness of the main results is further checked using alternative time-variant instruments, drawn from the existing literature on the determinants of ethnic fractionalization: per capita arable land, accounting for geographic factors that may have influenced spatial concentration and endogenous group formation (Ashraf and Galor 2013); time distance from the country foundation, based on the hypothesis that, in older countries, ethnic fusion or, conversely, ethnic conflicts, which reinforce ethnic identity, have had more time to take place affecting the degree of ethnic fractionalization (Kaufmann 2011 and 2015); the world and regional average levels of ethnic fractionalization, which can capture potential common trends at a global or regional level due to international issues like inter-country migration and global/regional economic and political dynamics (Gurr 2000; Campos and Kuzeyev 2007); the 30-year lagged values of ethnic fractionalization.Footnote 15The relevance of each of these alternative instruments is assessed through the Anderson-Rubin-Wald test and results are presented in Sect. 4.2 (Table 7).Footnote 16

Finally, a common practice to check the validity of the exclusion restrictions is to add the instrument to the set of right-hand side variables in the IV estimations. The exclusion restrictions for our main instrument, population density, is then assessed when it is included as a regressor in the IV estimations that use the above-mentioned alternative instruments for ethnic fractionalization. The validity of the exclusion restrictions is confirmed if the coefficient of the variable is either not statistically significant or close to zero (Table 8).

4 Results

Table 3 reports the panel estimates of Eq. 2 under different specifications for the whole sample and for the two sub-samples of developing and developed countries. Hausman specification test indicates a preference for the fixed-effects model over the random-effects estimator (columns 2, 5, 8 and 11). When ethnic fractionalization is instrumented with the measure of population density (columns 3, 6, 9 and 12), the Anderson-Rubin-Wald test confirms the relevance of the instrument. Moreover, both Hausman and Davidson-MacKinnon tests reveal a preference for the fixed-effects 2SLS-IV estimator, rejecting the hypothesis of exogeneity and confirming that ethnic fractionalization should be treated as endogenous. As a consequence, the fixed-effects instrumental variable estimator is preferred to the fixed-effects OLS regression in the whole sample as well as in the two sub-samples of countries. This choice is confirmed also when the lagged values of ethnic fractionalization are used as an alternative instrument: its relevance is confirmed again by the related Anderson-Rubin-Wald test (Table A4 in Appendix). Tables 4 and 5 report the results of 2SLS-IV regressions when the different areas, components and sub-components of the economic freedom index (EFI) are taken as dependent variables. While Table 4 shows the entire set of results for the five areas of economic freedom, Table 5 reports only the coefficients of ethnic fractionalization and their level of statistical significance for each component and sub-component of the five areas (full results are available upon request).

Considering the global EFI, ethnic fractionalization has a statistically significant effect in most of the different specifications and sub-samples, confirming that the level of economic freedom may be influenced by the degree of fractionalization (Table 3). In addition, the level of democracy and of respect of human and political rights turns out to play an important role in determining economic freedom. This is consistent with the extant empirical literature on the determinants of economic freedom, which finds that countries with freer political institutions and greater civil liberties have also higher degrees of economic freedom (see Lawson et al. 2020, for an accurate survey).

The coefficient of ethnic fractionalization has positive sign and is statistically significant in the whole sample and in the sub-sample of developing countries, but it takes the opposite sign–always being statistically significant–in the sub-sample of developed economies. This supports the idea that the dynamics that govern the relation between ethnic fractionalization and economic freedom differ according to the level of development. The results for the whole sample and the sub-sample of developing economies are consistent with some evidence already provided by the literature (and discussed in Sect. 2), which tries to explain the phenomenon claiming that ethnically diverse societies may find impetus in this diversity to improve their institutions in order to generate growth, as this last may appease social tensions due to ethnic differences (Alhassan and Kilishi, 2019). Nonetheless, the difference between developing and developed countries is a major reason to analyze the individual areas and components of the index more in depth and also calls for an assessment of the robustness of these initial results to the use of different specifications and samples. From a statistical point of view, indeed, the estimated effect on a composite variable represents the average effect on all its components. This could imply that, for instance, positive and negative forces may be at work and mutually cancel or reinforce their effects.

4.1 Decomposing the index of economic freedom

When considering the five areas included in the index, it emerges that the significant impact found on the overall level of economic freedom actually stems from the effects that fractionalization has on some areas only, as it does not show any statistical association with other areas (Table 4). Also in this case, results differ across the two sub-samples of countries. In particular, in developing countries ethnic fractionalization seems to have no impact on government size, while it increases all the remaining areas of economic freedom. The neutral effect on the size of government can be explained through the evidence already provided by the literature (Stichnoth and van der Straeten 2013): as discussed in Sect. 2, ethnic diversity may have the effect of increasing some items of public budgets, while decreasing others.

The positive association between ethnic fractionalization and the other areas of EFI may be explained through two channels. On the one hand, as ethnic diversity causes social tensions, the governments of ethnically fractionalized countries may have tried to foster economic growth by means of liberalizations with the aim of appeasing tensions through economic well-being (Olson 1982 and 2000). On the other hand, there may be another explanation for the positive contribution of ethnic fractionalization to economic freedom. Historically, countries with high levels of ethnic fractionalization have been more exposed to the risk of civil wars (Montalvo and Reynal-Querol 2005) and generally, when a civil war occurs, the higher the level of ethnic fragmentation, the higher the price paid by the country for the war (Costalli et al. 2017). Therefore, more ethnically fractionalized countries in the past may have resorted to international aid more often than the other developing countries. As international financial organizations provided aid conditional on the adoption of neoliberal reforms during the last twenty years of the twentieth century (the so-called Washington Consensus), there may be a positive correlation between ethnic fractionalization and the level of EFI (see Duffield 2002).Footnote 17 In Table 3 (columns 7, 8, 9) and Table 4, the effect of aid on EFI is tested for the period 2000–13, but no unambiguous and statistically significant effect is found. However, the liberal wave of the Washington Consensus that inspired the reforms suggested to developing economies was predominant in the 1980s and, especially, in the 1990s (Rodrik 2006 and Babb 2013), while in the subsequent years other reforms–more focused on the specific situation of each country/area and less centred on liberal policies–have been recommended by international donors. Therefore, the evidence presented here may not capture the effect of the first wave of reforms.

In developed countries, instead, ethnic fractionalization seems to influence the EFI negatively only through the freedom to trade internationally and the protection of personal and property rights. The absence of a statistically significant link with the degree of market regulation may depend on two opposite forces identified by the literature, especially regarding labour market freedom. On the one hand, the more liberal a country is, the larger the flows of immigration it attracts (i.e. it imports more ethnic diversity), as Wright (2012) shows. Therefore, one should expect to find a positive link between the level of labor market freedom and that of ethnic fractionalization.Footnote 18 On the other hand, the reluctance of the citizens of economically advanced countries to accept immigrants increases with the ethnic distance between themselves and the immigrants (Brader et al. 2008 and Ford 2011). Moreover, in liberal economies, firms may tend to prefer immigrant to domestic workers (Wright 2012),Footnote 19 thus increasing social tensions. This suggests that, when ethnic differences depend on immigration, they generate social tensions. As part of the response to these tensions during the first and a half decade of the twenty-first century, high-income countries tightened their market and social regulations (Ruhs 2018). The lack of a link between ethnic fractionalization and the degree of market regulations may therefore result from these opposite trends of openness and closure in the labour market.

Conversely, the negative relationship between ethnic fractionalization and trade freedom may depend, as the literature suggests, on the fact that in developed countries natives tend to react to immigration by increasing the consumption of national goods – giving rise to nationalist consumption (Balabanis et al. 2001 and Lekakis et al. 2017). Such behavior may explain why, as ethnic fractionalization increases, trade restrictions do as well: the governments of ethnically fractionalized countries may accommodate the increasing consumption nationalism through commercial closures and barriers against imported goods.

The association between ethnic fractionalization and the level of protection of personal and property rights, with ethnic fractionalization limiting rights, is instead unexpected in the light of the extant literature. Before commenting on this result, therefore, it is necessary to further unpack this indicator, studying the relationship between its sub-components and ethnic fractionalization; the same strategy will also apply to the other four areas of the index of economic freedom to understand whether their effects are actually the balance between different forces. What emerges is that as ethnic fractionalization increases, the quality of courts and the independence of judicial systems in developed countries seems to worsen. A possible explanation here is that where ethnic diversity is mainly an imported phenomenon, as it is in most of the economically advanced countries, the legal systems tend to accommodate natives’ opposition to immigration, being sterner with the members of minority (immigrated) ethnic groups (Steffensmeieri and Demuth 2000; Demuth and Steffensmeier 2004 and Leiber and Fix 2019). Such discriminations are likely to be stronger where immigration (and thus ethnic fragmentation) is larger. Ethnic discriminations may also affect the judicial systems of developing countries. However, as mentioned before, the more ethnically diverse countries are those that probably had more necessity to implement pro-growth reforms and that received more international aid in the past (and, therefore, more international pressures to improve their policies and their systems). In such process, aid may have been conditional on the reform of the judicial system that have decreased the ethnic bias in courts decisions.

In sum, Table 5 shows that all the five areas of the EFI represent aggregate measures, whose components and sub-components may be affected by ethnic fragmentation differently. These results suggest two main considerations: (1) the indices of economic freedom should be cautiously used by economists and policy-makers, as their composite nature may hide opposite dynamics; (2) ethnic fragmentation has diverging effects on the different areas, components and sub-components of the index of economic freedom, i.e. it affects different institutions diversely, depending on the characteristics and functions of the institutions themselves.

4.2 Robustness analysis

Table 6 shows the robustness analysis for regression in column 3 (full sample) and for the analogous regressions in columns 6 and 12 (developing and developed countries, respectively) of Table 3. To save space, only the estimates for the coefficient of ethnic fractionalization are reported, while full results are available upon request. First, the robustness of the results with regard to each specification is tested when the number of regressors is reduced. This allows for containing the problem of potentially bad controls. In row 1, the model includes only the main explanatory variable of interest, i.e. the index of ethnic fractionalization; the next specification includes the GDP per capita (row 2), and then also the Gini coefficient is included (row 3); finally, a model in which only the index of ethnic fractionalization and the two institutional variables (democracy and human rights) are present as regressors is estimated (row 4). The results are robust to all these specifications.

As a next step, the baseline model is estimated through the use of alternative methods. To assess the robustness of the results to the sample composition, the analyses employ jackknife (row 5) and bootstrap (row 6) techniques.Footnote 20 Both methods yield similar results which validate our previous findings. Moreover, since economic freedom may be persistent over time and the present changes in its level may depend on its previous levels, we also estimate a model where the dependent variable is expressed as the change in economic freedom, and the level of economic freedom at time t-1 is used as additional regressor, coherently with some existing studies (Haan and Sturm 2003; Lundström 2005; Pitlik and Wirth 2003; Pitlik 2008; Rode and Gwartney 2012). Also in this case, previous results are not significantly altered.

Furthermore, rows 8 to 13 examine alternative country samples. On one side, developing countries are divided into low and middle-income economies, and, on the other, non-OECD economies are excluded from the sample of developed countries. Next, former communist countries are left out from each of the three original samples. Moreover, while we found no outliers through the Hadi procedure (Hadi 1992), we alternatively exclude the ten countries with the most extreme values of economic freedom and ethnic fractionalization from the sample. Again, the value and the statistical significance of the coefficient for ethnic fractionalization do not notably change.

As specified in Sect. 3, the composition of the whole sample was the result of data availability, in particular with regard to the Gini coefficient. This led to an over-representation of African countries as well as to the exclusion of some other relevant economies. As a last step, we then try to extend the sample by dropping the Gini coefficient from the set of regressors (row 14). This allows for including a total of 130 countries. The analyses confirm the results for the developing countries. However, while the coefficient for ethnic fractionalization keeps its negative sign, it loses its statistical significance in the sub-sample of developed economies. Moreover, to explore the robustness of the results to the exclusion of specific developing regions, we alternatively exclude Sub-Saharan African, Asian and Latin American countries from the extended sample of developing economies (rows 15, 16 and 17 respectively). From this last step, it emerges that the statistical significance of previous results may be partially driven by the African countries. Indeed, while the results still hold when we alternatively exclude Asian and Latin American economies, the coefficient for ethnic fractionalization loses its statistical significance (although maintaining the positive sign) if Sub-Saharan African countries are left out. This may be partially due to the considerably lower average degree of ethnic fractionalization in the Latin American developing economies with respect to the Sub-Saharan African region (0.41 versus 0.68), as well as to the higher resistance of some Asian countries to the implementation of the full package of neo-liberal reforms during the Washington Consensus era and beyond (Beeson and Islam 2005; Lee 2006). However, conclusions should be cautiously drawn and this creates room for further research, as underlined in the next section.

Table 7 reports the results of the robustness analysis that employs the alternative instruments for ethnic fractionalization. While not reported to save space, the Anderson-Rubin-Wald tests always confirm the relevance of each alternative instrument, with the only exception of the 30-years lagged values of ethnic fractionalization when the full sample is analyzed. When the instruments are relevant, the results of the baseline models are fully confirmed and the coefficients are statistically significant in the majority of cases.

Finally, Table 8 shows the results when the IV estimations include our main instrument, population density, as a regressor. This procedure allows to test the validity of the exclusion restrictions, which is confirmed if the coefficient of the variable is either non-significant or close to zero. For the sub-samples of developing and developed countries, the coefficient for population density is not statistically significant and it only becomes statistically significant for the full sample, although its effect is very small (coefficient equal to 0.007). While these results are reassuring about the validity of our main instrument, at least in the two sub-samples of countries, they confirm the importance of verifying the robustness of the results by adopting also alternative instruments, since some weak correlation of the instrument with the error term may still exist.

5 Conclusions

The literature review and the empirical analysis provided in the paper highlight the complex relationship that exists between ethnic fractionalization and economic freedom. The main message that emerges is that high ethnic fragmentation is not necessarily linked to low levels of economic freedom, as some of the previous literature conversely suggests. In particular, some developing economies seem to exhibit the opposite pattern, while economically advanced countries show mixed evidence.

On the one hand, since ethnic diversity leads to social tensions, the governments of more fractionalized countries may have tried to promote economic growth through liberalizations with the aim of appeasing tensions through economic well-being (Olson 1982 and 2000; Alhassan and Kilishi, 2019). Moreover, a possible interpretation of the results is that also the liberal reforms proposed to aid-recipient countries in the wake of the Washington Consensus may have played a role. Indeed, more ethnically fragmented countries experienced more economic distress (because of tensions, riots, and civil wars) and, therefore, could have benefitted of international aids more than the others. As a consequence, these countries could also have received more international pressure to adopt liberal policies– at least in the 1980s and the 1990s. However, further research should inquire into these aspects more in depth.

On the other hand, while for most of the developing countries ethnic diversity is a condition inherited since their foundation and from colonial legacy (Vogt 2018); advanced economies, instead, have mostly imported their ethnic diversity through migration flows, which are generally directed towards economically freer countries. Nevertheless, in these countries, immigration may generate strong oppositions, asking for more regulation to protect the natives’ interests.

Further research, especially on the effects of immigration on economic freedom, is necessary to provide more support to these interpretations. Moreover, since the robustness analysis shows that the results for developing countries may be partially driven by African economies, further research should better investigate the different dynamics linking economic freedom and ethnic fractionalization at regional level, while the present conclusions are limited to the specific sample analyzed.

A second result of this paper is to provide evidence for the complex relationship between ethnic fractionalization and the index of economic freedom, through the effect on its different areas, components and sub-components. Indeed, the empirical analysis shows that the impacts of ethnic fractionalization on the composite index of economic freedom are the result of different effects; in particular, the value of some sub-components seems to decrease when ethnic fractionalization increases, while for others the opposite is true. This evidence is important for further research, which may consider focusing especially on those sub-components that have stronger and statistically significant links with ethnic fractionalization and on the reasons behind them.

Notes

Also Islam and Montenegro (2002) analyze how ethnic fragmentation is related to different indices of institutional quality and their components in large samples of countries. However, they do not specifically focus on economic freedom but rather on the quality of institutions in general.

The literature on this topic is vast; the aim of the paper is not, however, to survey it.

However, Pryor (2010) shows that Friedman’s claim should be mitigated, as economic freedom promotes political freedom through the educational system.

These domains are covered by most of the relevant indices. The legal framework is covered by the Fraser EFI index as “Legal system and property rights”, by the Heritage Foundation (HF) as “Rule of law” (heritage.org/index) and by the World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) (info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi). The level and quality of regulation is also covered by the three of them respectively as Regulation/Regulatory efficiency/Regulatory quality.

These domains are covered by the Fraser EFI and by the HF as Size of Government/Limited Government and Freedom to Trade internationally/Open markets respectively, while inflation and money soundness are a domain in the Fraser EFI (Sound Money) and a component of Monetary Freedom (under Regulatory efficiency) in the HF index. These domains are not covered by the WGI which includes instead: Voice and Accountability, Political Stability and Absence of Violence, Government Effectiveness, and Control of Corruption.

See Easterly (2003).

Our subsamples are based on the World Bank classification of countries operated according to their per capita GNI (Atlas methodology).

The number of components and sub-components ranges from four (for the area Sound Money) to eighteen (for the area Regulation). It should be noticed that a higher score always corresponds to more economic freedom, regardless the name of areas and components, which, in some cases, can be misleading. For example, countries scoring high in the area “Size of government” or in the component “Money growth” are the ones characterized by small size/growth, rather than big. Additional information can be found here: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/economic-freedom/approach

The Composition of Religious and Ethnic Groups project (CREG), initiated by the Cline Center for Democracy, is based on the Geo-Referencing of Ethnic Groups project (GREG), which was crosschecked and validated through the Britannica Book of the Year (BBOY), the CIA World Factbook (CIA-WF) and the World Almanac Book of Facts (WABF). The Encyclopaedia Britannica and the CIA World Factbook (CIA-WF) are also used by Alesina et al. (2003) for their proposed index. Compared to other similar indices, the main advantage of the CREG index is that the dynamics of ethnic groups are modelled and the shares are projected over time, thus allowing the calculation of a time variant index.

In the democ index, democracy is conceived as three elements: the presence of institutions and procedures through which citizens can express effective preferences about alternative policies and leaders, the existence of institutionalized constraints on the exercise of power by the executive, the guarantee of civil liberties to all citizens. See http://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html for details.

The dataset provides three separate indicators, each based on information contained in the annual reports published respectively by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the US Department of State Country Reports (Haschke 2017). Because of the high number of available observations, the authors prefer to rely on the last source.

The World Inequality Database initiative was started in 2011 and is funded by public and non-profit institutions, mostly European Universities and Research Centres: https://wid.world/data/.

The lag length was selected to maximize the time span under data availability constraints.

Also in this case, the choice of the lag length is driven by data availability.

To control for climatic factors, we also employed the average monthly temperature and the average monthly precipitation as alternative instruments for ethnic fractionalization (Ashraf and Galor, 2013). However, they turned out to be not relevant according to the Anderson-Rubin Wald tests.

Indeed, an ancillary regression of aid on ethnic fractionalization provides evidence of a positive and statistically significant association between these two variables.

However, this link works in the opposite direction of the phenomenon inquired in the analysis. Indeed, in this case, freedom affects ethnic fragmentation, and not vice-versa; therefore, if the IV approach used in the analysis is correct and solves the problems of reverse causality, this effect should not be detected – as indeed it is.

In addition, Finseraas et al. (2020) show that immigration in high-income countries has damaging effects on domestic workers especially in markets where labor unions are less diffused and have weaker bargaining power. Consequently, liberal markets may have seen an increase in labor force unionizing, with a decrease in economic freedom levels.

With jackknife method, the model estimation is replicated when each observation in the dataset is left out at a time, while bootstrapping iteratively resamples the dataset with replacements, drawing alternative random samples from the original data.

References

Acemoglu D, Fergusson L, Johnson S (2019) Population and conflict. Rev Econ Stud. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdz042

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson JA (2005) Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. In: Aghion P, Durlauf SN (eds) Handbook of economic growth. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 385–472

Ahlerup P, Olsson O (2012) The roots of ethnic diversity. J Econ Growth 17(2):71–102

Alesina A, Glaeser EL (2004) Fighting Poverty in the US and in Europe: a World of Difference. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Alesina A, La Ferrara E (2005) Ethnic diversity and economic performance. J Econ Literat 43(3):762–800

Alesina A, Baqir R, Easterly W (1999) Public goods and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ 114(4):1243–1284

Alesina A, Devleeschauwer A, Easterly W, Kurlat S, Wacziarg R (2003) Fractionalization. J Econ Growth 8(2):155–194

Alesina A, Easterly W, Matuszeki J (2011) Artificial states. J Eur Econ Assoc 9(2):246–277

Alhassan A, A., Kilishi, A.A. (2019) Weak economic institutions in Africa: a destiny or design? Int J Soc Econ 46(7):904–919

Alonso JA, Garciamartín C (2013) The determinants of institutional quality more on the debate. J Int Dev 25(2):206–226

Anderson TW, Rubin H (1949) Estimation of the parameters of a single equation in a complete system of stochastic equations. Ann Math Stat 20:46–63

Annett A (2001) Social fractionalization, political instability, and the size of government. IMF Staff Pap 48(3):561–592

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2):277–297

Ashraf Q, Galor O (2013) genetic diversity and the origins of cultural fragmentation. Am Econ Rev 103(3):528–533

Babb S (2013) The washington consensus as transnational policy paradigm: its origins, trajectory and likely successor. Rev Int Polit Econ 20(2):268–297

Baggio J, Payrakis E (2010) Ethnic diversity, property rights, and natural resources. Dev Econ 48(4):473–495

Balabanis G, Diamantapoulos A, Dentiste-Mueller R, Melewar TC (2001) The impact of nationalism, patriotism and internationalism on consumer ethnocentric tendencies. J Int Bus Stud 32:157–175

Beeson M, Islam I (2005) Neo-liberalism and East Asia: resisting the washington consensus. J Dev Stud 41(2):197–219

Bellemare MF, Pepinsky TB, Masaki T (2017) Lagged explanatory variables and the estimation of causal effects. J Polit 79(3):949–963

Berggren N (2003) The benefits of economic freedom: a survey. Independ Rev 8(2):193–211

Bond SR (2002) Dynamic panel data models: a guide to micro data methods and practice. Port Econ J 1:141–162

Brader T, Valentino NA, Suhay E (2008) What triggers public opposition to immigration? Anxiety, group cues, and immigration threat. Am J Polit Sci 52(4):959–978

Busse M, Hefeker C (2007) Political risk, institutions and foreign direct investments. Eur J Polit Econ 23(2):397–415

Campos NF, Kuzeyev VS (2007) On the dynamics of ethnic fractionalization. Am J Polit Sci 51(3):620–639

Casella A, Rauch J (eds) (2001) Networks and markets. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Casella A, Rauch J (2003) Overcoming informational barriers to international resource allocation: prices and ties. Econ J 113:21–42

Chadha N, Nandwani B (2018) Ethnic fragmentation, public good provision and inequality in India, 1988–2012. Oxf Dev Stud 46(3):363–377

Chong A, Gradstein M (2007) Inequality and institutions. Rev Econ Stat 89(3):454–465

Churchill SA, Smyth R (2017) Ethnic diversity and poverty. World Dev 95:285–302

Clark JR, Lawson R, Nowrasteh A, Powel B, Murphy R (2015) Does immigration impact institutions? Public Choice 163:321–335

Costalli S, Moretti L, Pischedda C (2017) The economic costs of civil war: Synthetic counterfactual evidence and the effects of ethnic fractionalization. J Peace Res 54(1):80–98

Davidson R, MacKinnon J (1993) Estimation and inference in econometrics. Oxford University Press, New York

De Haan J, Sturm JE (2000) On the relationship between economic freedom and economic growth. Eur J Polit Econ 16(2):215–241

De Haan J, Sturm JE (2003) Does more democracy lead to greater economic freedom? New evidence for developing countries. Eur J Polit Econ 19(3):547–563

De Soysa I (2011) Another misadventure of economists in the tropics? Social diversity, cohesion, and economic development. Int Area Stud Rev 14(1):3–29

De Soysa I, Almås S (2019) Does ethnolinguistic diversity preclude good governance? A comparative study with alternative data, 1990–2015. Kyklos 72(4):604–636

DeJong D, Ripoll M (2006) Tariffs and growth: an empirical exploration of contingent relationships. Rev Econ Stat 88(4):625–640

Demuth S, Steffensmeier D (2004) Ethnicity effects on sentence outcomes in large urban courts: comparisons among white, black, and Hispanic defendants. Soc Sci Q 85(4):994–1011

Dithmer J, Abdulai A (2017) Does trade openness contribute to food security? A dynamic panel analysis. Food Policy 69:218–230

Drazanova L (2019) Historical Index of Ethnic Fractionalisation Dataset.pdf, Historical Index of Ethnic Fractionalization Dataset (HIEF) https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/4JQRCL/2N5YVI&version=1.0

Duffield M (2002) Social reconstruction and the radicalization of development: aid as a relation of global liberal governance. Dev Chang 33(5):1049–1071

Easterly W (2003) The middle class consensus and economic development. J Econ Growth 6(4):317–335

Easterly W, Levine R (1997) Africa’s growth tragedy: public policies and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ 112(4):1203–1250

Faria HJ, Montesinos-Yufa HM, Morales DR, Navarro CE (2016) Unbundling the roles of human capital and institutions in economic development. Eur J Polit Econ 45:108–128

Finseraas H, Røed M, Schøne P (2020) Labour immigration and union strength. Eur Union Polit 21(1):3–23

Ford R (2011) Acceptable and unacceptable immigrants: how opposition to immigration in Britain is affected by Migrants’ region of origin. J Ethn Migr Stud 37(7):1017–1037

Friedman M (1982) Capitalism and freedom. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Glaeser EL, Saks RE (2006) Corruption in America. J Public Econ 90(6–7):1053–1072

Glaeser EL, La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Schleifer A (2004) Do institutions cause growth? J Econ Growth 9(3):271–303

Gibney M, Cornett L, Wood R, Haschke P, Arnon D (2017) The political terror scale 1976–2016. http://www.politicalterrorscale.org/.

Gurr TR (2000) People versus states: minorities at risk in the new century. United States Institute of Peace Press, Washington, D.C.

Gwartney J, Lawson R, Hall J, Murphy R (2019) Economic freedom of the world 2019 annual report. Fraser Institute https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/economic-freedom-of-the-world-2019.pdf

Gwartney, J. D., Lawson, R., Block, W., 1996. Economic freedom of the world, 1975–1995. Vancouver: The Fraser Institute.

Gwartney JD (2009) Institutions, economic freedom, and cross-country differences in performance. South Econ J 75(4):937–956

Gwartney JD, Lawson RA, Clark JR (2005) Economic freedom of the world, 2002. Independ Rev 9(4):573–593

Gwartney JD, Lawson RA, Holcombe RG (1999) Economic freedom and the environment for economic growth. J Inst Theor Econ 155(4):643–663

Hadi AS (1992) Identifying multiple outliers in multivariate data. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol) 54(3):761–771

Hall JC, Lawson RA (2014) economic freedom of the world: an accounting of the literature. Contemp Econ Policy 32(1):1–19

Hall JC (2016) Institutional convergence: exit or voice? J Econ Finance 40(4):829–840

Haschke P (2017) The political terror scale (PTS) codebook. University Of North Carolina, Asheville

Hausman JA (1978) Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica 46:1251–1271

Heckelman JC, Knack S (2008) Foreign aid and market-liberalizing reform. Economica 75(299):524–548

Heckelman JC, Wilson B (2018) Fractionalization and economic freedom. Public Finance Rev 46(2):158–176

Islam, R., Montenegro, C.E., 2002. What Determines the Quality of Institutions?. Policy Research Working Paper no. 2764. New York: The World Bank.

Karnane P, Quinn MA (2019) Political instability, ethnic fractionalization and economic growth. IEEP 16:435–461

Kaufmann E (2015) Land, history or modernization? explaining ethnic fractionalization. Ethn Racial Stud 38(2):193–210

Kaufmann E (2011) Ethnic and state history as determinant of ethnic fractionalization. SSRN: ssrn.com/abstract=1903676 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1903676

Krieger T, Meierrieks D (2016) Political capitalism: the interaction between income inequality, economic freedom and democracy. Eur J Polit Econ 45:115–132

La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Vishny RW (1999) The quality of government. J Law Econ Organ 15(1):222–279

Lawson R, Murphy R, Powell B (2020) The determinants of economic freedom: a survey. Contemp Econ Policy 38(4):622–642

Lee K (2006) The Washington consensus and east asian sequencing: understanding reform in east and South Asia. In: Fanelli JM, McMahon G (eds) Understanding market reforms. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Leiber MJ, Fix R (2019) Reflections on the impact of race and ethnicity on juvenile court outcomes and efforts to enact change. Am J Crim Justice 44:581–608

Lekakis EJ (2017) Economic nationalism and the cultural politics of consumption under austerity: the rise of ethnocentric consumption in Greece. J Consum Cult 17(2):286–302

Lundström S (2005) The effect of democracy on different categories of economic freedom. Eur J Polit Econ 21(4):967–980

Kilby C (2005) Aid and regulation. Q Rev Econ Finance 45(2–3):325–345

March RJ, Lyford C, Powell B (2017) Causes and barriers to increases in economic freedom. Int Rev Econ 64(1):87–103

Masella P (2013) National identity and ethnic diversity. J Popul Econ 26(2):437–454

Mauro P (1995) Corruption and growth. Q J Econ 110(3):681–712

Migheli M (2014) Preferences for government’s interventions in the economy: does gender matter? Int Rev Law Econ 39(1):39–48

Migheli M (2010) Supporting the free and competitive market in China and India: differences and evolution over time. Econ Syst 34(1):73–90

Mohr A, Shoobridge GE (2011) The role of multi-ethnic workforces in the internationalisation of SMEs. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 18(4):748–763

Montalvo JC, Reynal-Querol M (2005) Ethnic diversity and economic development. J Dev Econ 76(2):293–323

Murphy RH (2015) the impact of economic inequality of economic freedom. Cato J 35:117

Nardulli PF, Wong CJ, Singh A, Peyton B, Bajjalieh J (2012) The composition of religious and ethnic groups (CREG) project, cline center for democracy, University of Illinois at Urbana‐ChampaignCline https://clinecenter.illinois.edu/project/Religious-Ethnic-Identity/composition-religious-and-ethnic-groups-creg-project

Nikolaev B, Salahodjaev R (2017) Historical prevalence of infectious diseases, cultural values, and the origins of economic institutions. Kyklos 70(1):97–128

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

North, D.C., 2002. Institutions and Economic Growth: a Historical Introduction. In Frieden, J.A., Lake, D.A. (Eds.). International Political Economy. London: Routledge.

Norton SW (2000) The cost of diversity: endogenous property rights and growth. Const Polit Econ 11(4):319–337

Olson M (2000) Power and Prosperity. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Olson M (1982) The rise and decline of nations. Yale University Press, New Haven

Panizza U, Presbitero AF (2014) Public debt and economic growth: is there a causal effect? J Macroecon 41:21–41

Papyrakis E, Mo PH (2014) Fractionalization, polarization, and economic growth: identifying the transmission channels. Econ Inq 52(3):1204–1218

Parrotta P, Pozzoli D, Sala D (2016) Ethnic diversity and firms’ export behavior. Eur Econ Rev 89:248–263

Pitlik H, Wirth S (2003) Do crises promote the extent of economic liberalization? An empirical test. Eur J Polit Econ 19(3):565–581

Pitlik H (2008) The impact of growth performance and political regime type on economic policy liberalization. Kyklos 61(2):258–278

Polidano C (2000) Measuring public sector capacity. World Dev 28(5):805–822

Pryor FL (2010) Capitalism and freedom? Econ Syst 34(1):91–104

Reed WR (2015) On the practice of lagging variables to avoid simultaneity. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 77–6:897–905

Reilly B (2000) Democracy, ethnic fragmentation, and internal conflict. Int Secur 25(3):162–185

Rode M, Gwartney JD (2012) Does democratization facilitate economic liberalization? Eur J Polit Econ 28(4):607–619

Rodrik D (2007) One economics, many receipes. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Rodrik D (2006) Goodbye Washington consensus, hello washington confusion? A review of the World Bank’s “Economic Growth in the 1990s: learning from a decade of reforms.” J Econ Literat 44(4):973–987

Root HL (2018) Capital and Collusion. The political logic of global economic development. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Ruhs M (2018) Labor immigration policies in high-income countries: variations across political regimes and varieties of capitalism. J Legal Stud 47(S1):S89–S127

Sambanis N, Shayo M (2013) Social identification and ethnic conflict. Am Polit Sci Rev 107(2):294–325

Schlosky MT, Young A (2017) Can foreign aid motivate institutional reform? An evaluation of the HIPC Initiative. J Entrepreneurship Public Policy

Steffensmeier, D., Demuth, S. 2000. Ethnicity and Sentencing Outcomes in U.S. Federal Courts: Who Is Punished More Harshly? American Sociological Review 65(5), 705–729.

Stichnoth H, van der Straeten K (2013) Ethnic diversity, public spending, and individual support for the welfare state: a review of the empirical literature. J Econ Surv 27(2):364–389

Sunde U, Cervellati M, Fortunato P (2008) Are All democracies equally good? The role of interactions between political environment and inequality for rule of law. Econ Lett 99(3):552–556

Svensson J (1998) Investments, property rights and political instability: theory and evidence. Eur Econ Rev 42(7):1317–1341

Vogt M (2018) Ethnic stratification and the equilibrium of inequality: ethnic conflict in postcolonial states. Int Organ 72(1):105–137

Williamson CR, Mathers RL (2011) Economic freedom, culture, and growth. Public Choice 148(3–4):313–335

Wimmer A, Cederman LE, Min B (2009) Ethnic politics and armed conflict: a configurational analysis of a new global data set. Am Sociol Rev 74(2):316–337

Wood RM, Gibney M (2010) The political terror scale (PTS): a re-introduction and a comparison to CIRI. Hum Rights Q 32:367–400

Woodruff C (2006) Measuring institutions. In: Rose-Ackerman S (eds) International handbook of the economics of corruption. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Wright CF (2012) Immigration policy and market institutions in liberal market economies. Ind Relat J 43(2):110–136

Young AT, Sheehan KM (2014) Foreign aid, institutional quality, and growth. Eur J Polit Econ 36:195–208

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marson, M., Migheli, M. & Saccone, D. New evidence on the link between ethnic fractionalization and economic freedom. Econ Gov 22, 257–292 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-021-00259-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-021-00259-6