Abstract

Decisions on measures reducing environmental damage or improving environmental impact are usually constrained by financial limitations. Eco-efficiency analysis has emerged as a practical decision support tool by integrating environmental and economic performance. Environmental impact, as well as economic revenues and expenses, are usually distributed over a certain time scale. The temporal distribution of economic data is frequently assessed by discounting while discounting of environmental impact is rather uncommon. The scope of this paper is to reveal if this assumed inconsistency is common in eco-efficiency assessment literature, what reasons and interrelations with indicators exist and what solutions are proposed. Therefore, a systematic literature review is conducted and 35 publications are assessed. Theoretical eco-efficiency definitions and applied eco-efficiency indicators, as well as applied environmental and economic assessment methods, are compared here, but it is revealed that none of the empirical literature findings applied or discussed environmental discounting. It was, however, found in methodical literature. It is concluded that the theoretical foundation for the application of discounting on environmental impact is still insufficient and that even the theoretical foundation of economic discounting in studies is often poor. Further research and, eventually, a practical framework for environmental discounting would be beneficial for better-founded, more “eco-efficient” decisions.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Environmental decisions are often multi-dimensional. The most environmentally friendly alternative is not always affordable, meaning a trade-off between environmental impact and financial performance has to be made (Uhlman and Saling 2010). In consequence, a multi-dimensional assessment tool is required for assessing decisions regarding sustainability. An optimal choice between both the environmental and ecological dimensions can be called “eco-efficient” – this choice offers a minimum of environmental impact for a given financial budget or a minimum of costs for a certain environmental goal. Achieving eco-efficiency means “doing more with less” (Kuosmanen 2005). Nowadays, the majority of organizations tend to improve their “green” performance, with eco-efficiency being one of the main criteria (Rashidi and Saen 2015).

Usually, eco-efficiency is somehow quantified as the ratio of economic value added to the environmental damage index. The method includes the assessment of economic impacts, of environmental impacts, the discounting of both, and the aggregation of different environmental impacts to a single score (Kuosmanen 2005). Huppes and Ishikawa (2005) distinguish four main types of eco-efficiency: environmental productivity (positive value per negative environmental impact) and its inverse, environmental intensity of production, as well as environmental improvement cost (negative value per positive environmental impact) and its inverse, environmental cost-effectiveness. ISO 14045:2012 (ISO 2012), defines: “Eco-efficiency assessment is a quantitative management tool which enables the study of life-cycle environmental impacts of a product system along with its product system value for a stakeholder”. The environmental dimension has to be assessed by Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which is standardized in ISO 14040 and 14044. For the assessment of the economic dimension, ISO 14045 does not point to a standard but states “The value of the product system may be chosen to reflect, for example, its resource, production, delivery or use efficiency, or a combination of these. The value may be expressed in monetary terms or other value aspects”.

Kuosmanen (2005) recognized that, in many applications, economic costs and benefits as well as environmental impacts occur over long time spans. This results in the need for discounting to make reasonable long-term decisions by EEA. Lueddeckens et al. (2021) reviewed the perceptions and applications of discounting in LCA in the scientific literature. They found that there is an ongoing debate on discounting which partly results from misunderstandings of the discounting concept. Discounting is a decision instrument for intertemporal decisions on the utility of various things, e.g. money or environmental impact. Discounting is not limited to money, as it can be applied to any utility. Those utilities have different values for people at different points in time and an anthropocentric instrument like LCA or EEA should recognize that. Multidimensional information – the temporal distribution of the environmental or economic information – can be condensed to a single value, namely the net present value, through the application of discounting, the principle of which is the evaluation of utility. People have not only a preference for near-term utility, but also incur opportunity costs for their actions. For example, if one investment option would lead to an immediate reduction of environmental damage and another, same-priced option would lead to a little higher reduction but in many years in the future, then without discounting one would have to choose the future option, which is intuitively not preferable. Furthermore, the decision for this future option would, for example, mean rejecting the near-term option, which is a missed opportunity and would lead to opportunity costs. Additionally, due to economic growth, external costs today will have lower relative value in the future.

Kuosmanen (2005) stated that there is always discounting, at least implicitly, in both dimensions in an eco-efficiency analysis. There is no possibility to avoid a decision on the discounting function, as a decision for a zero discount rate would also be a value judgement that should be well founded (Lueddeckens et al. 2020). A discount rate of zero implies, that the author gives future environmental impact the same value as immediate impact.

There are numerous arguments supporting the consistent application of discounting in intertemporal decisions. Not doing so would violate basic principles of human decision-making, would ignore opportunity costs and economic development, and would be misleading in decisions. Nevertheless, the specific shaping of the discounting method needs further investigation. Lueddeckens et al. (2021) stated that discounting is an individual decision instrument, which depends on the alternative choices and opportunity costs of the individual decision maker. Nevertheless, a framework for the derivation of a discounting function should help the decision maker to provide reasonable and accepted results.

The development of such framework requires a survey of the status quo of the application of discounting in EEA literature so that the framework could base on previous knowledge and practice and further develop previous ideas. A review on discounting in EEA could not be found. Kuosmanen (2005) is an editorial and Lueddeckens et al. (2021) a narrative review, focusing on environmental discounting in general. In a systematic review, Lueddeckens et al. (2020) only searched for discounting in life cycle assessments. As only titles and abstracts were included in the search, EEA literature was potentially not found, although LCA will usually occur in the full text of EEA literature. The review’s scope was not to find practical instructions on how to discount but to discuss reasons, subjectivity and limitations of discounting in a theoretical way. A systematic review by Caiado et al. (2017) focused on sustainable development and how EEA could contribute to it. The research questions were “How does eco-efficiency contribute to sustainable development?”, “What are the barriers and synergies between sustainable development and eco-efficiency?” and “Based on these above questions, how can this knowledge be synthesized in an integrative conceptual framework of sustainability and eco-indicators?”. While answering the last question, Caiado et al. (2017) gave hints for an EEA framework that could contain discounting but they did not include discounting in their search term. Available EEA frameworks like the one of Huppes and Ishikawa (2005) and Uhlman and Saling (2010) do not mention discounting. A comprehensive overview of the application of discounting in EEA as a foundation for further framework developments is missing.

Therefore, a systematic literature review is conducted here to investigate how discounting is applied in current EEA literature, depending on the applied EE measures. The review is specifically motivated by the desire to uncover if discounting is applied in an inconsistent way, discounting the economic dimension but not the ecological one and, if so, for which reasons.

Methods

The method of choice for discovering current scientific knowledge on discounting in EEA in a comprehensive and comprehensible way is the systematic literature review, which is conducted in the following, sticking to Fink’s (2014) manual for this method. According to Littell et al. (2008), the aim of a systematic review is “to comprehensively locate and synthesize research that bears on a particular question, using organized, transparent, and replicable procedures at each step in the process.” This method is applied as a structured approach to answer the presented research question and to make it easy for future research to adapt this review, which could be expanded to future literature or to other linked research questions. For the transformation of the found information into new knowledge, the systematic review must be combined with analysis methods. Tranfield et al. (2003) suggest applying content analysis methods in order to extract relationships and opinions or in combination with meta-analysis to extract data. A content analysis is applied to answer the theoretical questions on methods and reasons for and against discounting as well as for analyzing methods for economic and environmental assessments and concrete discount functions. Zumsteg et al. (2012) introduced systematic literature reviews with content analysis for LCA meta-studies.

The four steps of a systematic review proposed by Fink (2014) are followed, in combination with the structure proposed by Tranfield et al. (2003).

In the first step, the research questions are defined, along with appropriate bibliographic databases and search terms. The search results were selected by practical review criteria and then synthesized. The research questions are as follows:

-

(1)

How is EEA defined?

-

(2)

Which measures are used to assess the environmental and economic dimensions?

-

(3)

What reasons and assumptions are given for the application or non-application of discounting in EEA, and based on which theories?

-

(4)

What are the discounting functions being used?

-

(5)

How is discounting interpreted, and are there, for example, scenario or sensitivity analyses?

The search term included eco AND efficien* or eco-efficien* in the title in order to identify literature on specific EEA or methodical literature like frameworks. Further, discoun* is searched in the full text, while in Web of Science, where this is not possible, only in title, abstract, and keywords. Results with and without discoun* are compared to get an idea of the presence of discounting in EEA literature.

Scopus and Web of Science databases are included because they have proven to list the most journals for environmental assessment issues (Caiado et al. 2017; Lueddeckens et al., 2021). The search was expanded to include Ebsco Environmental Source Complete, which is a special database for environmental topics and completed with Google Scholar.

In the second step of a systematic review according to Fink (2014), the procedure for the selection of literature has to be defined by inclusion and exclusion criteria. Only journal articles in English were included. They may be of conceptual, theoretical, or empirical nature and must be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal to ensure meaningful results. Other findings from grey literature (dissertations, master theses, book chapters, conference proceedings) were screened but provided no additional information of a quality comparable to the scientific literature. Reviews were also excluded. The search results were then screened for relevance to the research questions.

In the third step of a systematic review according to Fink (2014), positively identified papers enter the content analysis. Papers were analyzed by utilizing a tabular review protocol. The protocol contains bibliographic data, the object of the EEA, definition of EEA, and applied indicators, economic and ecological assessment methods, and information on discounting in the form of short summaries in bullet points and for quantifiable information (see Fig. 3) the numerical or Boolean value. Paragraphs in the reviewed papers containing relevant information were coded in the Citavi software, corresponding to the review protocol’s categories.

Finally, in the fourth step, the review ends with a synthesis of findings, which is discussed in the next section. Method and search results are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Results and discussion

The search in Scopus yielded only 12 results. Three of those and no new papers were found on Web of Science. Ebsco Environmental Search Complete also yielded only 3 results which were already found in Scopus. However, Google Scholar yielded 94 results. The complete search was conducted on the 10th of November 2020. Apparently, there are no suitable databases for searching for EEA or they were not available to the author. Google Scholar is not a database but a search engine that delivers diverse results according to the search engine’s algorithms. It is a less reliable source for a systematic review than scientific databases and it is not fully reproducible. One paper was only found in Scopus, but not by the search engine. All other database entries were also found by Google Scholar so there were 95 findings in total. Sixty of those were sorted out by quality criteria (peer-reviewed journal papers) or were not relevant or accessible. Non-relevant findings usually used the word “discount” in the meaning of an immediate discount a supplier may offer for instant payments, large order quantities, or other reasons. For three findings, the full text was not available to the author of this paper (see Appendix 1).

There were 5930 results without searching for discounting in Google Scholar. So only 1.6% of the EE literature in Google Scholar mentions discounting.

Bibliographic data

Many papers had been published quite recently, especially in the years 2019 and 2020 (Fig. 2), which indicates a growing interest in discounting in EEA. The most relevant journals were the Journal of Cleaner Production and the Journal of Industrial Ecology (Table 1). There were many findings in technical journals, often dealing with eco-efficiency of a specific technical application. For this reason, it might be hard to find a suitable literature database for a comprehensive search.

Assessed branches in the sample

The assessed objects in the reviewed EEA can be assigned to six categories: energy supply, production of goods, waste treatment, buildings, transportation/tourism, and water supply. Six publications are conceptual and do not focus on a special assessment object (Table 2).

EE definitions

None of the publications is older than the WBCSD definition of eco-efficiency from 1992. Of the 35 publications in total, 20 publications refer to its definition of eco-efficiency. Eleven publications cite the newer definition of ISO 14045 from 2012, while 7 cite both. This means 11 publications do not refer to those key definitions. Nevertheless, none of the publications contradict the WBCSD definition with regard to the content. Of the 25 publications from 2012 and later, more than half (13) does not refer to the ISO 14045 definition. This could indicate that this standard is not generally accepted or available or not suitable for every use case, e.g. if the environmental dimension is not assessed by life cycle assessment (4 of the 13 cases). All publications that cite ISO 14045 apply LCA for assessing the environmental dimension, as specified by ISO.

Alternative definitions for EE found in the literature are highlighted in the following. According to Kuosmanen (2005) “Eco-efficiency means ‘doing more with less,’ or producing economic output with minimal natural resources and environmental degradation.” Evin and Ucar (2019) stated that “Eco-efficiency is usually described as a ratio between two elements: environmental impact, to be reduced, and value of production, to be increased”. For Mangili et al. (2019), EE is the relationship between any environmental variable and any economic variable, with several possible EE indicators. Rodrigues and Freire (2017) define EE as “creating value while decreasing environmental impact”, and Tichavska and Tovar (2015) define it as “creating more goods and services by reducing the related environmental impact”.

EE-Indicators

The EE indicators used in the reviewed literature cannot completely be classified according to the four main types of EE by Huppes and Ishikawa (2005). Ten of 32 publications (Table 3) used the environmental productivity type or the environmental improvement costs type of indicators, expressed in money per LCA result. Six publications used the inverse, environmental intensity or environmental cost-effectiveness, of which four calculated in LCA result per money unit and two in LCA result per product quantity. This means 16 of 32, or half of the publications, can be classified into these four categories. As this approach would correspond best to the EE definition in ISO 14045, it would be reasonable to assume that these 16 publications would cite the norm when explaining their method. However, only 3 of these publications cite ISO 14045 while 13 don’t. Four of those 13 publications were published before 2012. Evenly widespread is the approach to summing up or multiplying an environmental and an economic score, where all of the reviewed publications gave both dimensions the same weight. In three publications, the indicator was 1/(LCA result × LCC result). Higher EE in this indicator requires smaller environmental damage or smaller costs. Two publications chose the product of economic productivity (product quantity per cost) and environmental productivity (product quantity per environmental damage) as an EE indicator. Quite similar to this is the portfolio method of presenting EE results, which was used in seven publications. In accordance with the BASF method (Saling 2016), the economic and environmental results were not weighted and were equally opposed. Two publications simply added up the LCA and LCC scores, weighting them equally with ½. Less common, with only one case each, was the use of qualitative scores and monetization of environmental impacts, which allowed for the summation of economic and environmental results.

Assessment methods

LCA is applied in 27 publications for the assessment of the environmental dimension. This included partial LCAs where the full range of indicators is not used. In 21 publications, the LCA results were either weighted or aggregated by data envelopment analysis. Frequent characterization and weighting methods include Eco-Indicator99, IMPACT2002 + , ReCiPe, and CML2002. Those authors who do not use weighting present EE indicators for every single impact category.

Life Cycle Costing (LCC) is applied in 23 publications for the assessment of the economic dimension in several varieties. Most authors called their methods LCC, but there are also mentions of TCO (total cost of ownership), DGC (dynamic generation costs), total economic value added, levelized costs of electricity, and the annuity method, which can be regarded as subcategories of LCC. Other assessment methods are cost–benefit analysis for a greater scale, financial calculations of investment costs, ongoing costs, and revenues without regarding the whole life cycle, and non-financial value indicators. These include landings and take-offs of planes (D’Agosto and Ribeiro 2004), passenger numbers, cargo tons and ship calls (Tichavska and Tovar 2015). Zhao et al. (2011) normalized the LCC to the Chinese GDP, as well as the LCA to Chinese environmental impacts. Mutanov et al. (2019) assessed environmental and economic indicators qualitatively on a 1–10 scale.

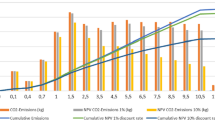

Discounting in EEA

In 32 publications, standard exponential discounting is applied to the financial data, but only 15 publications provided an explanation of the derivation of the discount rate. This means more than half of the publications discount at arbitrary rates. The mean discount rate is 7.3%, ranging from 2 to 18%, and it seems to depend on the year of publication (later publications have lower rates), the industry sector, the currency, and country. However, a statistical analysis was not performed because of the small number of findings. In five publications, inflation is considered in the discount rate. This outcome shows that discounting is a highly individual measure and that no general suggestions for a discount rate can be made.

Environmental discounting is only proposed by two conceptual publications (Kuosmanen 2005; Kulczycka and Smol 2015) but no practical examples were found in the assessed EEA literature. Ghimire and Johnston (2017) state that the “sustainability analysis of systems with high temporal variation (such as long vs short service lives) should be done carefully”. Unless the authors recognized temporal issues and discuss weighting of environmental impacts in detail, they did not recognize temporal weighting (discounting). The existence of “temporal issues” is also mentioned by Huppes and Ishikawa (2005), but the simplification of methods is regarded as important for ensuring widespread use. The authors state a “lack of agreement on discounting when long time horizons are involved” in relation to environmental impacts but also long-term financial issues. They regard discounting as the only practical problem in the well-established economic assessment methods. They also argue that the discounting problem is even more prominent in the environmental dimension due to long time horizons of impacts and major sustainability considerations of intergenerational justice. This is confirmed by Kulczycka and Smol (2015) who regard discounting as one of the main challenges in EEA. For the environmental dimension, a lower discount rate compared to the economic dimension is suggested because “the ecological effects of property are not subject to the same rules as the amount of capital used in economic processes”. The social discount rate is proposed, referring to the Stern report, which used 1.4% (1.3% for opportunity costs of growth, 0.1% for the possibility of the annihilation of mankind). Hellweg et al. (2005) state that expenses after the time horizon of 100 years would not play a big role in the assessment because of discounting. Interestingly, they argue that this would be similar to environmental impact – because the abatement costs for impacts after 100 years would be small due to discounting, future impacts could be discounted right away.

Kuosmanen (2005) finds discounting necessary in all dimensions of EEA due to opportunity costs and time preference. Nevertheless, he stated that “the ultimate objective of an eco-efficiency study should be borne in mind, meaning that discounting at too high rates could offend principles of sustainability”. Mutanov et al. (2019) discuss discounting only for the economic dimension and prefer not to use it on long time horizons. It is stated that decision makers would need a decision instrument without discounting because discounting would lead to false long-term decisions due to the large effect of a discount function on the outcome. In contrast, Zhang et al. (2019) waived economic discounting because it would have little effect within their short time horizon. They generally recommend not to discount in “environmental LCC”. According to Joachimiak-Lechman et al. (2019), discounting environmental damage is debatable and not recommended by specialists, which makes the LCA a “steady-state” analysis. Unfortunately, they do not cite any literature with which to confirm this viewpoint. The only authors besides Kuosmanen (2005) who find it inconsistent to discount only the economic but not the environmental dimension are Zhao et al. (2011). They state methodical differences in LCC and LCA that would justify discounting in LCC and disregarding discounting in LCA, but if both are applied together in an EEA, then they suggest a “steady state LCC” without discounting.

Figure 3 summarizes the aforementioned findings. The raw data can be found in the Appendix 2.

The Google Scholar search yielded further results that were excluded due to quality requirements, especially the need for a peer review in a scientific journal. Nevertheless, some interesting perspectives could be found in some of them. Kortelainen and Kuosmanen (2017) suggest to discount environmental impact if its monetary value is constant over time so that it can be monetized later. They suggested not to discount because of time preference because that would not exist for environmental issues in their opinion. The reason for discounting include, according to them, the opportunity costs of the environmental costs, the foregone interest of invested capital. To be consistent, they suggested to discount monetary and environmental costs at the same constant rate. According to Huppes and Ishikawa (2007), discounting is an even more prominent problem in the environmental than in the monetary dimension, especially because there is no consensus on discounting in long time horizons, which are, in some impact categories, longer than for the monetary calculation. Discounting could also offend considerations on intergenerational justice.

Appendix 2 provides details of the assessed literature.

Conclusions

The hypothesis made at the beginning proved true—discounting in the economic and ecological dimensions in EEA are handled inconsistently in the available EEA literature that mentions discounting. In most EEA, the economic dimension is discounted, while none of the authors discounted the ecological dimension. Only a minority of authors provided thoughts on discounting environmental impact. Astonishingly, most authors did not even provide explanations for their choice of the economic discount rate. It seems as though discounting is often regarded as a method that needs to be implemented somehow, someway, without considering the high impact discounting may have on assessment outcome and decisions made thereupon. The use of generic discount rates can also be a symptom of the authors having no “real world” decision problem that, for example, a company would have when choosing its supply parts. In the end, probably there was no individual discount rate and discounting was only applied in an illustrative manner. In this case, an explanation would be beneficial for understanding. Authors are advised to better justify their choice of discount functions as this choice can be very decisive in the outcome. Only 1.6% of the literature indexed in Google Scholar with EE in the title mention discounting, which is a strikingly small share when compared to the high impact and relevance of discounting. Discounting seems to have a low popularity among authors of EE literature and should become more popular in the future. The same applies to the acceptance of ISO 14045, although this finding is not representative, due to the limitation of the search term of this review. A not fully accepted ISO norm would be an obstacle for further standardisations, like a standardisation of a discounting procedure.

Unfortunately, this review could not find relations between the choice of assessment methods, understanding of EE or application of financial discounting and environmental discounting. There was also no relationship between the application of weighting of impact types and temporal weighting (discounting). An unexpected finding is that several authors proposed to solve the inconsistency problem by avoiding discounting completely, calling it “steady-state” analysis or “LCA-like LCC”, both without discounting.

Due to the highly individual nature of discounting, the avoidance of discounting in EEA seems appropriate if the EEA has an informative character. For example, if a decision maker compares different EEA, then this comparison would be distorted by discounted information, which may differ in both EEA and may also be different from the individual discount rates of the decision maker. In this case, temporally distributed information should be provided so that the decision-makers could discount themselves.

Nevertheless, a guideline for discounting in EEA with suggestions for the derivation of the discount rate would be very helpful and should be developed. The following ideas can be taken from this review, even though they do not represent consensus but only hints given in the assessed publications:

-

1.

Discounting methods must be comprehensible for both, decision makers and stakeholders, e.g. showing similarities to known financial discounting methods.

-

2.

The simplification of methods is regarded as important for ensuring widespread use.

-

3.

Intergenerational justice and the overall principle of sustainability is a concern when thinking of discounting – discounting very long-term impact should not lead to its complete marginalization. Declining (like hyperbolic) discount functions could fulfil this criterion.

-

4.

The theory of the social discount rate could be a hint for the development of environmental discounting, as the environment is a common good.

This systematic review is, like every systematic review, limited especially by its search strategy. Other search terms, for example in other languages, or other databases may have yielded different results. The reviewer’s bias and misinterpretations of the assessed literature can also influence the results. Nevertheless, within its limitations this review gives the first comprehensive overview of the state of the scientific knowledge about discounting in EEA and may prove helpful for researchers immersing in this topic with much potential for future research.

Outlook and future research

Thoughts on discounting are rarely mentioned in EE literature. Nevertheless, there may exist non-written knowledge. In future research, expert interviews could provide additional insights. A multidisciplinary approach might be beneficial, especially for generating knowledge about discounting the environmental dimension. Experts in the fields of LCA, business research, economics, social sciences and philosophy could be interviewed. For assessing the social discount rate as a proxy for environmental discounting, experts may also be found in central banks and ministries of finance.

Environmental Cost–Benefit-Analysis is a method that originates from economics and has similarities to EEA. A systematic review may discover knowledge on discounting that can be applied to EEA.

Furthermore, it could be interesting to compare opinions from scientific experts and practitioners in companies. Although it was recommended to apply discounting to intertemporal data for both economic and environmental data in decision-making by EEA, providing guidance on how to do that in practice goes beyond the scope of this paper. Discounting is ultimately an individual evaluation and depends on the decision maker. A discount function for every purpose cannot be provided. Nevertheless, a guideline or framework for environmental discounting should be developed to overcome the inconsistency compared to economic discounting in EEA. This review proofs that this research gap remains largely unaddressed.

References

Alizadeh S, Zafari-koloukhi H, Rostami F, Rouhbakhsh M, Avami A (2020) The eco-efficiency assessment of wastewater treatment plants in the City of Mashhad using emergy and life cycle analyses. J Clean Prod 249:119327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119327

Arceo A, Biswas WK, John M (2019) Eco-efficiency improvement of Western Australian remote area power supply. J Clean Prod 230:820–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.106

Arceo A, Rosano M, Biswas WK (2018) Eco-efficiency Analysis for remote area power supply selection in Western Australia. Clean Techn Environ Policy 20(3):463–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-017-1438-6

Anwar M, Siti NB, Alvarado V, Hsu S-C (2021) A socio-eco-efficiency analysis of water and wastewater treatment processes for refugee communities in Jordan. Resour Conserv Recycl 164:105196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105196

Belucio M, Rodrigues C, Antunes CH, Freire F, Dias LC (2020) Eco-efficiency in early design decisions: a multimethodology approach. J Clean Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124630

Breedveld L, Timellini G, Casoni G, Fregni A, Busani G (2007) Eco-efficiency of fabric filters in the Italian ceramic tile industry. J Clean Prod 15(1):86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.08.015

Burchart-Korol D, Krawczyk P, Czaplicka-Kolarz K, Smoliński A (2016) Eco-efficiency of underground coal gasification (UCG) for electricity production. Fuel 173:239–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.01.019

Caiado RGG, de Freitas Dias R, Mattos LV, Quelhas OLG, Leal W, Filho. (2017) Towards sustainable development through the perspective of eco-efficiency - a systematic literature review. J Clean Prod 165:890–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.166

Chakrabarty S, Islam T (2011) Financial viability and eco-efficiency of the solar home systems (SHS) In Bangladesh. Energy 36(8):4821–4827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2011.05.016

Cruz PL, Iribarren D, Dufour J (2019) Life cycle costing and eco-efficiency assessment of fuel production by coprocessing biomass in crude oil refineries. Energies 12(24):4664. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12244664

Czaplicka-Kolarz K, Burchart-Korol D, Krawczyk P (2010) Eco-efficiency analysis methodology on the example of the chosen polyolefins production. J Achieve Mater Manuf Eng 43(1):469–475

D’Agosto M, Ribeiro SK (2004) Eco-efficiency management program (EEMP)—a model for road fleet operation. Transp Res Part D Transp Environ 9(6):497–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2004.09.001

Evin D, Ucar A (2019) Energy impact and eco-efficiency of the envelope insulation in residential buildings in Turkey. Appl Therm Eng 154:573–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.03.102

Faragò M, Brudler S, Godskesen B, Rygaard M (2019) An eco-efficiency evaluation of community-scale rainwater and stormwater harvesting in Aarhus, Denmark. J Clean Prod 219:601–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.265

Fink A (2014) Conducting research literature reviews: from the internet to paper, 4th edn. SAGE, Los Angeles

Frischknecht R (2010) LCI modelling approaches applied on recycling of materials in view of environmental sustainability, risk perception and eco-efficiency. Int J Life Cycle Assess 15(7):666–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-010-0201-6

Ghimire SR, Johnston JM (2017) A modified eco-efficiency framework and methodology for advancing the state of practice of sustainability analysis as applied to green infrastructure. Integr Environ Assess Manag 13(5):821–831. https://doi.org/10.1002/ieam.1928

Hellweg S, Doka G, Finnveden G, Hungerbühler K (2005) Assessing the eco-efficiency of end-of-pipe technologies with the environmental cost efficiency indicator. J Ind Ecol 9(4):189–203. https://doi.org/10.1162/108819805775247864

Huppes G, Ishikawa M (2005) A framework for quantified eco-efficiency analysis. J Ind Ecol 9(4):25–41. https://doi.org/10.1162/108819805775247882

Huppes G (2007) Why we need better eco-efficiency analysis: from technological optimism to realism. Technikfolgenabschätzung Theorie Und Praxis 16(3):38–45

Huppes G, Ishikawa M (2007) An introduction to quantified eco-efficiency analysis. In: Tukker A, Charter M, Ehrenfeld J, Huppes G, Lifset R, de Bruijn T, Ishikawa M (eds) Quantified eco-efficiency, vol 22. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 1–38

ISO 14045 (2012) Environmental management – eco-efficiency assessment of product systems – principles, requirements and guidelines. International Organization for Standardization

Jankovic S, Vejzagic V, Vlašić D (2011) Tourist destination integral product eco-efficiency. IBER. https://doi.org/10.19030/iber.v10i1.928

Joachimiak-Lechman K, Selech J, Kasprzak J (2019) Eco-efficiency analysis of an innovative packaging production: case study. Clean Tech Environ Policy 21(2):339–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-018-1639-7

Kortelainen M, and T Kuosmanen (2017) Data envelopment analysis in environmental valuation: environmental performance, eco-efficiency cost-benefit analysis: working paper https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/15166799.pdf

Krawczyk P, Śliwińska A (2020) Eco-efficiency assessment of the application of large-scale rechargeable batteries in a coal-fired power plant. Energies 13(6):1384. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13061384

Kulczycka J, Smol M (2015) Application LCA for eco-efficiency assessment of investments projects. Acta Innov 16:29–38

Kuosmanen T (2005) Measurement and analysis of eco-efficiency: an economist’s perspective. J Ind Ecol 9(4):15–18. https://doi.org/10.1162/108819805775248025

Littell JH, J Corcoran, and VK Pillai. (2008) Systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Pocket guides to social work research methods. Oxford University Press: Oxford

Lueddeckens S, Saling P, Guenther E (2020) Temporal issues in life cycle assessment—a systematic review. Int J Life Cycle Assess 25(8):1385–1401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-020-01757-1

Lueddeckens S, Saling P, Guenther E (2021) Discounting and life cycle assessment: a distorting measure in assessments, a reasonable instrument for decisions. Int J Environ Sci Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-021-03426-8

Mami F, Revéret J-P, Fallaha S, Margni M (2017) Evaluating eco-efficiency of 3D printing in the aeronautic industry. J Ind Ecol 21(S1):S37–S48. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12693

Mangili PV, Junqueira PG, Santos LS, Prata DM (2019) Eco-efficiency and techno-economic analysis for maleic anhydride manufacturing processes. Clean Techn Environ Policy 21(5):1073–1090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-019-01693-1

Müller K, Holmes A, Deurer M, Clothier BE (2015) Eco-efficiency as a sustainability measure for kiwifruit production in New Zealand. J Clean Prod 106:333–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.07.049

Muradin M, Joachimiak-Lechman K, Foltynowicz Z (2018) Evaluation of eco-efficiency of two alternative agricultural biogas plants. Appl Sci 8(11):2083. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8112083

Mutanov G, Ziyadin S, Shaikh A (2019) Graphic model for evaluating the competitiveness and eco-efficiency of eco-innovative projects. JESI 6(4):2136–2158. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2019.6.4(41)

Tatari O, Kucukvar M (2012) Eco-efficiency of construction materials: data envelopment analysis. J Constr Eng Manag 138(6):733–741. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000484

Rashidi K, Saen RF (2015) Measuring eco-efficiency based on green indicators and potentials in energy saving and undesirable output abatement. Energy Econ 50:18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2015.04.018

Rodrigues C, Freire F (2017) Adaptive reuse of buildings: eco-efficiency assessment of retrofit strategies for alternative uses of an historic building. J Clean Prod 157:94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.104

Saling P (2016) The Basf eco-efficiency analysis: a 20-Year Susscess Story. Ludwigshafen: BASF SE

Tainter J (2003) A framework for sustainability. World Futures J Gen Evol 59(3–4):213–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604020310132

Tichavska M, Tovar B (2015) Environmental cost and eco-efficiency from vessel emissions in las Palmas port. Transp Res Part E Logist Transp Rev 83:126–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2015.09.002

Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P (2003) Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br J Manag 14(3):207–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00375

Uhlman BW, Saling P (2010) Measuring and communicating sustainability through eco-efficiency analysis. Chem Eng Prog 106(12):17–29

Valente A, Iribarren D, Gálvez-Martos J-L, Dufour J (2019) Robust eco-efficiency assessment of hydrogen from biomass gasification as an alternative to conventional hydrogen: a life-cycle study with and without external costs. Sci Total Environ 650(Pt 1):1465–1475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.089

Woon KS, Irene ML (2016) An integrated life cycle costing and human health impact analysis of municipal solid waste management options in Hong Kong using modified eco-efficiency indicator. Resour Conserv Recycl 107:104–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.11.020

Zhang C, Mingming Hu, Dong L, Gebremariam A, Miranda-Xicotencatl B, Di Maio F, Tukker A (2019) Eco-efficiency assessment of technological innovations in high-grade concrete recycling. Resour Conserv Recycl 149:649–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.06.023

Zhao W, Huppes G, van der Voet E (2011) Eco-efficiency for greenhouse gas emissions mitigation of municipal solid waste management: a case study of Tianjin, China. Waste Manag 31(6):1407–1415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2011.01.013

Zhao X, Zhang C, Bai S (2020) Eco-efficiency of end-of-pipe systems: an extended environmental cost efficiency framework for wastewater treatment. Water (switzerland) 12(2):454. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12020454

Zumsteg JM, Cooper JS, Noon MS (2012) Systematic review checklist: a standardized technique for assessing and reporting reviews of life cycle assessment data. J Ind Ecol 16(Suppl 1):S12–S21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00476.x

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The author declares that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript. The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Data availability

The data used for this review is publically available as cited in the references list. Appendix 2 provides an overview.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Search results (DOI) which could not be reviewed due to limited access: https://doi.org/10.4018/ijaeis.2014100103, https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5445-5.ch012, https://doi.org/10.30638/eemj.2019.

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lueddeckens, S. A review on the handling of discounting in eco-efficiency analysis. Clean Techn Environ Policy 25, 3–20 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-022-02397-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-022-02397-9