Abstract

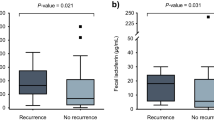

Calprotectin and lactoferrin are released by the gastrointestinal tract in response to infection and mucosal inflammation. Our objective was to assess the usefulness of quantifying faecal lactoferrin and calprotectin concentrations in Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) patients with or without free toxins in the stools. We conducted a single-centre 22-month case–control study. Patients with a positive CDI diagnosis were compared to two control groups: group 1 = diarrhoeic patients negative for C. difficile and matched (1:1) to CDI cases on the ward location and age, and group 2 = diarrhoeic patients colonised with a non-toxigenic strain of C. difficile. Faecal lactoferrin and calprotectin concentrations in faeces were determined for patients with CDI and controls. Of 135 patients with CDI, 87 (64.4%) had a positive stool cytotoxicity assay (free toxin) and 48 (35.6%) had a positive toxigenic culture without detectable toxins in the stools. The median lactoferrin values were 26.8 μg/g, 8.0 μg/g and 15.8 μg/g in CDI patients and groups 1 and 2, respectively. The median calprotectin values were 218.0 μg/g, 111.5 μg/g and 111.3 μg/g, respectively. Among patients with CDI, faecal lactoferrin and calprotectin levels were higher in those with free toxins in their stools (39.2 vs. 10.2 μg/g, p = 0.003 and 274.0 vs. 166.0 μg/g, p = 0.051, respectively). Both faecal calprotectin and lactoferrin were higher in patients with CDI, especially in those with detectable toxin in faeces, suggesting a correlation between intestinal inflammation and toxins in stools.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati GK, Dunn JR, Farley MM, Holzbauer SM, Meek JI, Phipps EC, Wilson LE, Winston LG, Cohen JA, Limbago BM, Fridkin SK, Gerding DN, McDonald LC (2015) Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med 372(9):825–834

Bartlett JG (2006) Narrative review: the new epidemic of Clostridium difficile-associated enteric disease. Ann Intern Med 145(10):758–764

Hensgens MP, Dekkers OM, Goorhuis A, LeCessie S, Kuijper EJ (2014) Predicting a complicated course of Clostridium difficile infection at the bedside. Clin Microbiol Infect 20(5):O301–O308

Leffler DA, Lamont JT (2015) Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 373(3):287–288

Barbut F, Surgers L, Eckert C, Visseaux B, Cuingnet M, Mesquita C, Pradier N, Thiriez A, Ait-Ammar N, Aifaoui A, Grandsire E, Lalande V (2014) Does a rapid diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection impact on quality of patient management? Clin Microbiol Infect 20(2):136–144

Davies KA, Longshaw CM, Davis GL, Bouza E, Barbut F, Barna Z, Delmée M, Fitzpatrick F, Ivanova K, Kuijper E, Macovei IS, Mentula S, Mastrantonio P, von Müller L, Oleastro M, Petinaki E, Pituch H, Norén T, Nováková E, Nyč O, Rupnik M, Schmid D, Wilcox MH (2014) Underdiagnosis of Clostridium difficile across Europe: the European, multicentre, prospective, biannual, point-prevalence study of Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalised patients with diarrhoea (EUCLID). Lancet Infect Dis 14(12):1208–1219

Crobach MJ, Planche T, Eckert C, Barbut F, Terveer EM, Dekkers OM, Wilcox MH, Kuijper EJ (2016) European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the diagnostic guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 22(Suppl 4):S63–S81

Polage CR, Gyorke CE, Kennedy MA, Leslie JL, Chin DL, Wang S, Nguyen HH, Huang B, Tang YW, Lee LW, Kim K, Taylor S, Romano PS, Panacek EA, Goodell PB, Solnick JV, Cohen SH (2015) Overdiagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection in the molecular test era. JAMA Intern Med 175(11):1792–1801

Planche T, Wilcox M, Walker AS (2015) Fecal-free toxin detection remains the best way to detect Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 61(7):1210–1211

Langhorst J, Boone J (2012) Fecal lactoferrin as a noninvasive biomarker in inflammatory bowel diseases. Drugs Today (Barc) 48(2):149–161

Boone JH, Archbald-Pannone LR, Wickham KN, Carman RJ, Guerrant RL, Franck CT, Lyerly DM (2014) Ribotype 027 Clostridium difficile infections with measurable stool toxin have increased lactoferrin and are associated with a higher mortality. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 33(6):1045–1051

Swale A, Miyajima F, Roberts P, Hall A, Little M, Beadsworth MB, Beeching NJ, Kolamunnage-Dona R, Parry CM, Pirmohamed M (2014) Calprotectin and lactoferrin faecal levels in patients with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI): a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 9(8):e106118

Popiel KY, Gheorghe R, Eastmond J, Miller MA (2015) Usefulness of adjunctive fecal calprotectin and serum Procalcitonin in individuals positive for Clostridium difficile toxin gene by PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 53(11):3667–3669

LaSala PR, Ekhmimi T, Hill AK, Farooqi I, Perrotta PL (2013) Quantitative fecal lactoferrin in toxin-positive and toxin-negative Clostridium difficile specimens. J Clin Microbiol 51(1):311–313

El Feghaly RE, Stauber JL, Deych E, Gonzalez C, Tarr PI, Haslam DB (2013) Markers of intestinal inflammation, not bacterial burden, correlate with clinical outcomes in Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 56(12):1713–1721

Kuijper EJ, Coignard B, Tüll P; ESCMID Study Group for Clostridium difficile; EU Member States; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2006) Emergence of Clostridium difficile-associated disease in North America and Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 12(Suppl 6):2–18

McDonald LC, Coignard B, Dubberke E, Song X, Horan T, Kutty PK; Ad Hoc Clostridium difficile Surveillance Working Group (2007) Recommendations for surveillance of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 28(2):140–145

Johnson S, Louie TJ, Gerding DN, Cornely OA, Chasan-Taber S, Fitts D, Gelone SP, Broom C, Davidson DM; Polymer Alternative for CDI Treatment (PACT) investigators (2014) Vancomycin, metronidazole, or tolevamer for Clostridium difficile infection: results from two multinational, randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 59(3):345–354

Cornely OA, Crook DW, Esposito R, Poirier A, Somero MS, Weiss K, Sears P, Gorbach S; OPT-80-004 Clinical Study Group (2012) Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double-blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 12(4):281–289

Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, Weiss K, Lentnek A, Golan Y, Gorbach S, Sears P, Shue YK; OPT-80-003 Clinical Study Group (2011) Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 364(5):422–431

Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB (2007) A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis 45(3):302–307

Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, Ananthakrishnan AN, Curry SR, Gilligan PH, McFarland LV, Mellow M, Zuckerbraun BS (2013) Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol 108(4):478–498

Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Kelly CP, Loo VG, McDonald LC, Pepin J, Wilcox MH; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America (2010) Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 31(5):431–455

Whitehead SJ, Shipman KE, Cooper M, Ford C, Gama R (2014) Is there any value in measuring faecal calprotectin in Clostridium difficile positive faecal samples? J Med Microbiol 63(Pt 4):590–593

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding/support

The study was sponsored by the Association Robert Debré pour la Recherche Médicale. Astellas provided a research grant to the Association Robert Debré pour la Recherche Médicale based on the study protocol.

Astellas had no role in the study design and conduct, and was not involved in the data collection, data management, or data analysis and interpretation. Astellas provided editorial assistance with grammar and English language editing.

Conflict of interest

Frédéric Barbut reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Astellas, personal fees from Pfizer, grants and personal fees from Sanofi Pasteur, grants and non-financial support from Anios, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from MSD, grants from bioMérieux, grants from Quidel Bühlmann, grants from Diasorin, grants from Cubist, grants from Biosynex and grants from GenePoc; Catherine Eckert reports non-financial support from Astellas and Mobidiag.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee and presented to the Infection Control Committee.

Informed consent

No.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 13 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barbut, F., Gouot, C., Lapidus, N. et al. Faecal lactoferrin and calprotectin in patients with Clostridium difficile infection: a case–control study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 36, 2423–2430 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-017-3080-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-017-3080-y