Abstract

Background

In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the progressive cognitive impairment is often combined with a variety of neuropsychiatric symptoms, firstly depression. Nevertheless, its diagnosis and management is difficult, since specific diagnostic criteria and guidelines for treatment are still lacking. The aim of this Delphi study is to reach a shared point of view among different Italian specialists on depression in AD.

Methods

An online Delphi survey with 30 questions regarding epidemiology, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatment of depression in AD was administered anonymously to a panel of 53 expert clinicians.

Results

Consensus was achieved in most cases (86%). In the 80% of statements, a positive consensus was reached, while in 6% a negative consensus was achieved. No consensus was obtained in 14%. Among the most relevant findings, the link between depression and AD is believed to be strong and concerns etiopathogenesis and phenomenology. Further, depression in AD seems to have specific features compared to major depressive disorder (MDD). Regarding diagnosis, the DSM 5 diagnostic criteria for MDD seems to be not able to detect the specific aspects of depression in AD. Concerning treatment, antidepressant drugs are generally considered the main option for depression in dementia, according to previous guidelines. In order to limit side effects, multimodal and SSRI antidepressant are preferred by clinicians. In particular, the procognitive effect of vortioxetine seems to be appealing for the treatment of depression in AD.

Conclusions

This study highlights some crucial aspects of depression in AD, but more investigations and specific recommendations are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dementia currently affects 24 million individuals worldwide, and, with population aging, its prevalence is expected to quadruple by 2050 [1]. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia in older adults, while other types such as vascular, Lewy body, and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) are less common. While progressive cognitive impairment is the hallmark of AD, neuropsychiatric symptoms affect almost all patients and are persistent [2]. Depression is one of the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD, associated with institutionalization and mortality [3].

A recent meta-analysis established that the prevalence of major depression was 15.9% and 14.8% in all-cause dementia and in AD, respectively [4]. Multiple lines of evidences suggest that the link between depression and neurodegenerative disease is strong. It is well known that the presence of chronic depression increases the risk of dementia later in life [5], while the emergence of new depressive symptoms in older adults can precede the diagnosis of cognitive decline and dementia. Further, the occurrence of major depressive disorder (MDD) in AD may accelerate cognitive and functional decline [6]. Finally, depression has a strong negative influence on conversion to AD in patients with mild cognitive impairment [7]. Despite these data, depression in AD is still underdiagnosed and, therefore, undertreated most likely as a consequence of the lack of consistent diagnostic criteria to assess depression in this context [8]. A major limitation to the diagnosis of depression in AD is the potential overlap between symptoms of depression and symptoms resulting from the cognitive and functional decline. Another limitation could be the paucity of instruments specifically designed to assess depression in dementia.

Once depression has been diagnosed in AD patients, the treatments are still controversial. Antidepressants represent the first choice of treatment for AD patients with depression. This is due to a lack of alternative treatment options and a perception that antidepressants are effective in this population [9]. On the other hand, there is not clear evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses to support this practice. A recent meta-analysis including 7 studies found no statistically significant difference between antidepressants and placebo [10]. At the same time, clear indications for preferring a specific antidepressant drug group over another are still lacking and antidepressant drug is chosen on the basis of clinical practice guidelines (CPG) or consensus on either AD or depression, or on the basis of the empirical expertise of clinicians [11]. However, the most recent multimodal antidepressant vortioxetine was not included in previous meta-analysis [10] but it may be considered as a promising alternative for the treatment of depression in patients with AD. In fact, in addition to blocking the serotonin transporter (SERT), vortioxetine has a complex interaction with different 5-HT receptors leading to the modulation of different neurotransmitters, including acetylcholine (Ach) [12]. Because of these pharmacodynamics characteristics, a possible role on improving cognitive deficits has been described and investigated. Some previous studies demonstrated the efficacy of vortioxetine on cognitive symptoms in elderly depressed patients [13,14,15,16]. Two studies investigated the efficacy on cognitive functions in patients with mild or moderate AD, with conflicting results [17, 18]. Finally, the role of antidementia medications (acetylcholinesterase inhibitors) on depressive symptoms is still debated [19, 20]. In summary the approach to depression in AD is quite different among physicians and clear guidelines are still lacking. Consequently this topic has been the objects of different Consensus Delphi in many countries [21] in different settings [22].

The aim of this Delphi study is to reach a shared point of view among different specialists on the diagnosis and management of depression in AD in Italy.

Methods

The Delphi method is an approach frequently used in scientific and medical contexts aimed at reaching consensus among a group of experts, when scientific evidence is limited or conflicting [23, 24]. Our study is a modified Delphi study with only one round, therefore different from the classic model which provides a series of “n” rounds to allow respondents to review their initial assessments until a certain degree of convergence of the panel’s views. The aim was to measure, within the Italian reality, the level of consensus/perception on some aspects of the management of depression in Alzheimer’s disease. The study consisted of the administration of an online survey to a panel of specialists in neurology, psychiatry, and geriatrics. A steering committee composed by nine distinguished physicians (7 neurologist, 1 psychiatrist, 1 geriatrician) in the field of Alzheimer’s disease formulated 30 questions. The questions were discussed during an online meeting, reflecting the more debated aspects of phenomenology, diagnosis, and management of depression in AD in order to encourage a food for thought among panelists. The questionnaire was administered anonymously and the 30 statements were grouped in 4 sections (Depression and neurodegenerative disease—Clinical features of depression in AD—Diagnostic criteria of depression in AD—Treatment of depression in AD). For each statement of the questionnaire, participants had to express their degree of agreement or disagreement according to the following 5-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = agree; 4 = more than agree; 5 = strongly agree. In accordance with the Delphi standards, a positive consensus were reached when the sum of items 3, 4, and 5 (agree) reaches 66%, while a negative consensus were obtained if more than 66% of answers were 1 ad 2 (disagree). No consensus was reached when the sum of the responses for a negative consensus (1 and 2) or a positive consensus (3, 4, and 5) was <66%. Participants responded to the 30 items of the questionnaire on only one round. The second round was not administered because there is no available literature on the 4 items that have not reached the consensus.

Populations

Nine distinguished physicians (7 neurologist, 1 psychiatrist, 1 geriatrician) in the field of Alzheimer’s disease constituted the Steering Committee that designed the study, drafted the questionnaire, analyzed, and discussed the results. Further, the Steering Committee identified the panel of specialists that participate to the Delphi method with the following skills: neurologist or geriatrician; at least 10-year experience on Alzheimer’s disease—visiting at least 10 patients per week; gender balance (50% women)—equally allocated in the various Italian areas—selected throughout the study group on the base of academic roles, scientific publications. Each member of the Steering Committee proposed 5 to 8 physicians with these skills as panelists.

Fifty-three physicians (41 neurologist, 12 geriatrist) were invited by email to answer to the online Delphi questionnaire. No personal data were collected from the panel of experts, with the exception of the email addresses that were used only for sending invitation and reminder emails. All the data from the questionnaire were analyzed in an anonymous way.

Results

The Delphi survey was presented to the panel of experts. Of 53 invited physicians, 46 completed the questionnaire. Data from the Delphi questionnaire are reported: overall, consensus was achieved in most cases (26 statements; 86%). Specifically, 24 statements (80%) obtained positive consensus, while only 2 statements (6%) achieved a negative consensus. Finally, no consensus was obtained in 4 statements (14 %). Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4 show all Delphi statements according to 4 sections (Depression and neurodegenerative disease—Clinical features of depression in AD—Diagnostic criteria of depression in AD—Treatment of depression in AD). No consensus or consensus, and if so, either agreement or disagreement is reported for each statement. The distribution of preferences among the five scores is also specified.

In the section “Depression and neurodegenerative disease,” participants achieved an agreement in 4 statements (80%), while 1 statement reached no consensus (20%) (Table 1). Regarding the section “Clinical features of depression in AD,” 6 statements (75%) achieved an agreement, 1 (12.5%) a disagreement, and 1 resulted in no consensus (12.5%) (Table 2). In the field of Diagnostic criteria of depression in AD (Table 3), 2 agreements (66.6%) and 1 no consensus (33.3%) was reported. Most participants agreed on the importance of specific diagnostic tools, while it was no consensus if the clinical judgment alone is enough to diagnose depression. Finally, regarding treatments, an agreement was obtained in 12 statements (86%), a disagreement in 1 statement (7%), and a no consensus in 1 statement (7%) (Table 4).

Discussion

The aim of this Delphi study was to reach a common point of view on depression in AD among a large numbers of specialists and to encourage a serious consideration on the most debated questions that make difficult the management of a depressed patient with AD. Globally considered, the results of the present study are in the expected direction, reflecting the current knowledge and the literature on depression in AD. Hereafter, the results are discussed according to the principal items.

Depression and neurodegenerative disease

Even if the issue of whether depression is an AD-associated prodromal condition or a risk factor is controversial [4], all the participants agreed on the presence of a temporal link between depression and neurodegenerative disease (s.1.1). This result is in line with a growing body of evidence and with the positioning of medical societies such as the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the American Psychiatric Association (APA), and the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP).

These medical societies recommend regular depressive symptom appraisal in older adults with dementia and assessment of other secondary causes. Most specialists also believed that depressive symptoms are directly related to the neuropathological features of Alzheimer’s disease (s.1.3). Nevertheless, previous studies investigating the link between depressive symptoms and neuropathological changes in clinical AD found conflicting results [25, 26]. Some prospective-cohort studies described that patients with AD and history or diagnosis of depression had higher levels of neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles [25]; instead other cross-sectional studies failed to associate CSF biomarkers of AD and depressive symptom in AD [26]. Regardless of the association between AD pathology and depression, depressive symptoms are recognized as an integral part of the symptomatology of AD that frequently affects patients (s.1.2, s.1.4); therefore, most specialists believed that AD does not affect only cognitive dimension. After all, since 1996 the spectrum of non-cognitive and non-neurological symptoms of dementia, such as agitation, aggression, psychosis, depression, and apathy, was described with the term “Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia” (BPSD) by the International Psychogeriatric Association (IPA) [27].

The most debated question of this section concerns the use of the diagnostic criteria of major depressive disorder (MDD) as described by DSM-V to diagnose depression in AD (s.1.5). No consensus was reached among the specialists, as well as a clear recommendation from scientific reports is still lacking. In fact, these criteria appear not specific in the context of AD, since they do not take in account the presence of the cognitive impairment and the overlap between cognitive and affective symptoms. Consequently, some peculiar features of depression in AD are not considered: in example, suicidal ideation and sense of guilt are infrequent, while anhedonia is often exacerbated [8]. A workgroup convened by the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) proposed standardized diagnostic criteria for depression in AD (NIMH-dAD) [28]. These are similar to the DSM-V criteria for major depression, but with the inclusion of irritability and social isolation replacing loss of libido, and with loss of pleasure in response to social contact replacing loss of interest. Nevertheless, the NIMH-dAD criteria are frequently unknown and are not regularly used by specialists.

Clinical features of depression in AD

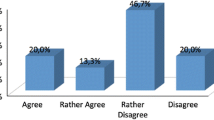

In the section “Clinical features of depression in AD,” the opinion of the specialists on the phenomenology of depression in AD is explored. Even if most of statements reached a consensus, the major number of preferences belongs to the point 3 (agree) of the 5-point Likert scale, suggesting a not very strong consensus on these themes.

The affective dimension of depression in AD is well defined in the opinion of specialists that identified the presence of anhedonia and the absence of suicidal ideation as remarkable features of depression in AD (statement 2.6, 2.7), according to the phenomenology of depression in AD as described by many authors [8].

The link between cognitive and affective symptoms is more debated. According to the Cumming’s hypothesis, affective symptoms of AD are ascribed to the cholinergic deficiency (s.2.1) [29].

Therefore, depression is considered as a distinct entity from cognitive impairment, such that depressive symptoms and the extent of cognitive impairment are not correlated in the opinion of the participants (s.2.5). Effectively, a systematic review did not find a significant association between severity of AD and prevalence of depressive symptoms in three of the four high quality included studies [30]. Even if frontal and prefrontal executive deficit is significantly impaired during, and between, depression episodes in not demented individuals with major depressive disorder, nevertheless no consensus was reached on the presence of executive deficits in depressed patients with AD (s.2.4). Probably the participants believed that it is not possible to distinguish executive deficits due to AD from that due to depression. This data reveals a more general limitation of clinical and neuropsychological assessment of depressed patients with AD that concerns the complex overlap between cognitive and affective dimension. As confirmation, most specialists believed that in patients with AD, depressive symptoms and anxiety can make difficult a suitable assessment of cognitive disturbances (s.2.2), underlying the challenge to separate cognitive and affective aspects and the complex interaction between the two. Actually different profiles between cognitive deficits in depression and dementia have been frequently described [31], but most specialists feel not confident in using these investigations in clinical practice. Finally, the bidirectional relationship between AD and major depressive disorder is investigated. In this context, answers of participants were in the expected direction. On one side, participants agreed on the increased risk of developing AD in patients with medical history of depressive disorder or bipolar disorder (s.2.3); on the other they believed that the risk of developing a major depressive disorder is not the same in patients with AD and in general population (s.2.8). Concerning the first statement, it is in line with most studies that demonstrate that a history of both depression and bipolar disorder is associated with significantly higher risk of dementia in older adults [4]. Further, when depression occurs late in life, it acts as a dementia risk factor (cause) or an early sign (prodrome) of an underlying neurodegenerative disease typically associated with AD. This interconnection seems to be dependent on age, depression severity, and success of antidepressant treatment [32]. It has been considered that late-onset depression might be a prodromal condition of AD due to short time lag between the onsets. A recent meta-analysis, which included 23 community-based prospective cohort studies, concluded that late-life depression significantly increased the risk of AD incidence for 1.65 fold, even after considering all possible confounders [33]. On the other hand, if there was a long time lag between the onsets, depression was usually considered more of a risk factor than a prodromal condition [4]. On the other hand, the participants appear to be aware of the high prevalence of depression in patients with AD (s.2.8), according to a recent meta-analysis [3] that indicates that individuals with dementia have an increased prevalence of major depressive disorder (14.8%) when compared to individuals without dementia, where depression prevalence is approximately 1.8% [34]. Further, the prevalence of depression in AD varies greatly in different investigations, depending on the diversity in research methodology, diagnostic criteria for depression, and patient samples. For example, studies using specific diagnostic criteria for depression in AD such as NIMH-dAD criteria [28] suggested higher depressive prevalence of around 50% [35], while those using categorical diagnostic criteria such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) indicated comparatively lower prevalence of around 10–40% [36].

Diagnostic criteria of depression in AD

All the experts agreed on the importance of recognizing the cognitive disturbances associated to depressive symptoms (s.3.2). Patients with major depressive disorder often experience impairment in cognitive functions in several domains, including executive functioning, processing speed, concentration/attention, learning, and memory [37], such that impairment in cognition is included in the diagnostic criterion for major depressive disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5. Nevertheless, low cognitive performance in depressed adults can be an artifact for AD diagnosis. On the other hand, the absence of cognitive improvement upon depressive symptom remission may suggest an ongoing neurodegenerative process; considering that around one third of the adult population with depression is diagnosed with concomitant mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [38], the recognition of cognitive impairment in depressed patients is crucial to drive the follow-up of these patients.

The most debated question is how depressive symptoms have to be diagnosed in patients with AD. In fact, no consensus was reached regarding the use of only clinical examination as diagnostic tool, while most specialists agreed on the utility of specific diagnostic scales. As already discussed, these results confirmed that the phenomenology of depressive symptoms in AD runs away a clear systematization and useful diagnostic tool and diagnostic criteria are still lacking. Consequently, the diagnostic scales as the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia, the Geriatric Depression Scale, or the Beck Depression Inventory, can be useful, but clinicians are still confident in their clinical judgment, underlying the difficulty to put depressive symptoms in the context of the cognitive impairment of AD.

Treatment of depression in AD

In this section, the opinion of specialists on different therapeutic alternatives for the treatment of depression in AD was explored. All the participants agreed that the choice of the antidepressant drug for a depressed patient with AD must be driven by its tolerability and safety profile (s.4.7). In fact, a growing body of evidence reveals that the use of antidepressant drugs is associated with an increased risk of adverse effects and events in older people, such as nausea, diarrhea, falls, hip fractures, cardiovascular events, all-cause mortality, and orthostatic hypotension [39]. Quite the opposite, the efficacy of antidepressant drugs in AD has not been proven by a recent review [40]. According to these data, the guidelines of the APA Work Group on Alzheimer’s Disease and other Dementias for treating depression in AD suggest the use of antidepressants with minimal and the least severe adverse effects as the first-line approaches [41]. Regarding the side effects of antidepressant drugs, there is a mild consensus on the association between use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and restless leg syndrome (s.4.9). A recent study found a potential harmful association between movement disorders and use of various antidepressants (mirtazapine, vortioxetine, amoxapine, phenelzine, tryptophan, fluvoxamine, citalopram, paroxetine, duloxetine, bupropion, clomipramine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, mianserin, sertraline, venlafaxine, and vilazodone) [42]. Nevertheless, the specialists do not believe that SSRI and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) such as multimodal one can worsen cognitive and motor symptoms in AD (s.4.3). Maybe this inconsistency is due to the belief that cognitive symptoms can take advantage from antidepressant therapy, as demonstrated by some previous studies [12]. Further, the increased occurrence of REM behavior disorder during antidepressant therapy can make difficult the differential diagnosis between Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. No consensus was reached in the field of tricyclic antidepressant. It is not clear, in fact, if specialists are confident in the use of these drugs according to the age of patients (s.4.2). Maybe some specialists believe that age from birth certificate is not a pressing criterion, while physiological age and other aspects need to be considered.

Once the antidepressant drug has been chosen, treatment regimens should last 3 months at least, in the opinion of most specialists. It is reasonable considering that the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on depression advise a minimum of 6-month treatment [43].

Concerning the ideal features of the antidepressant therapy in AD, the panel focuses on the efficacy on anhedonia (s.4.5), that is believed as the main symptom of depression in AD, as already discussed, and on cognitive symptoms (s.4.6). According to these preconditions, most specialists identified SSRI and the multimodal antidepressant as a valid therapeutic choice for treating depression in AD (s.4.4). This result is in line with most guidelines, based largely on clinical experience [40].

In the opinion of specialists, vortioxetine, the new multimodal antidepressant, may have some potential benefits on anhedonia and on cognitive symptoms. Effectively, a previous study on a large population of patients with MDD showed significant short- and long-term efficacy against anhedonia [44, 45]. Regarding the procognitive effects of vortioxetine, they were thought to be related to the agent’s modulation of neurotransmitters, and less likely related purely to improvements in depressive symptoms [12]. On the other hand, a previous study showed that in patients with AD vortioxetine had a beneficial effect on cognitive performances, even if compared with other antidepressant drugs [17]. This data has been confirmed in a very recent analysis of a post-marketing surveillance [46]. Quite the opposite, a recent double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with AD showed no differences in terms of depressive symptoms, cognitive function, and impact on daily living activities in subjects treated with vortioxetine compared to placebo [18]. Nevertheless, even if few and conflicting data are actually available on the efficacy of vortioxetine in AD, considering the mechanism of action of this drug and previous data on its procognitive effect [47,48,49], vortioxetine seems to be a promising alternative in patients with AD and depression in the opinion of most panelists.

It is believed by most specialists that serotoninergic antidepressant could act with antidementia medication—specifically cholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs)—on mood and cognition in a synergistic manner. A previous study confirmed that in AD patients treated with AChEIs, SSRIs may exert some degree of protection against the negative effects of depression on cognition [43]. The authors found that patients depressed and not treated with SSRIs worsened in terms of mean change of MMSE score compared with those depressed and treated with SSRI. Further, also cholinesterase inhibitors could have some effects on depression: donepezil has been found to be associated with improvement of depression in AD patients, which was measured mainly by screening tools for BPSD [50]. Also rivastigmine and galantamine have been proven to improve depressive symptoms in patients with AD [19, 20], even if with conflicting results [51]. On the other hand, in vitro studies demonstrated that SSRIs are able to interfere with the APP metabolism in vitro [52].

Finally, non-pharmacological therapies are considered. A mild consensus was reached on the effectiveness of cognitive-behavior therapy (s.4.11). Various international guidelines [41, 43] suggest that therapy for depression in dementia should include a variety of non-pharmacologic options, as cognitive behavioral therapy, reminiscence therapy, multi-sensory stimulation, animal-assisted therapy, exercise, and stimulation-oriented treatment, even though with a lower degree of evidence [11]. Probably all non-pharmacological therapies need to be more considered and an extensive knowledge and employment of these options is still lacking between specialists.

Conclusion

The results of this Delphi questionnaire highlight some crucial aspects of depression in AD. Depression in older adults represents a risk factor for dementia and in some conditions is considered a prodromal condition; the consequence in clinical practice is that depressed people have to be carefully evaluated regarding cognitive disturbances and their development. Further, depression in the context of AD seems to have specific features in comparison with major depressive disorder. Nevertheless, the accurate background and assessment of depressive symptoms in AD still represents a challenge for the clinicians, because the complex overlap between affective and cognitive symptoms makes the cognitive assessment and the administration of specific scales for mood difficult.

The complex interaction between depression and dementia is probably due to a shared pathogenetic background that includes different neurotransmitter systems, firstly the cholinergic system. In consequence of the specificity of depressive symptoms in AD and of their difficult assessment, the clinicians do not refer to any diagnostic criteria. In fact, the DSM 5 diagnostic criteria for MDD are not able to detect the specific aspects of depression in presence of dementia. Concerning treatment, although evidence is mixed, antidepressant drugs are generally considered the main option for depression in dementia, according to previous guidelines. In order to limit side effects, SSRIs and the most recent multimodal antidepressant are preferred by clinicians. In particular, the procognitive effect of vortioxetine such as the effect on anhedonia seems to be appealing for the treatment of depression in AD.

In summary, this work integrates the opinions of a group of Italian specialists in a wide debate on depression in AD and contributes to this topic trying to explain the most controversial etiological and clinical aspects of depression and dementia. Furthermore, some clinical aspects, as the use of reliable diagnostic criteria, are still unmet and require future investigations and specific recommendations.

References

Reitz C, Mayeux R (2014) Alzheimer disease: epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, risk factors and biomarkers. Biochem Pharmacol 88(4):640–651

Fernández M, Gobartt AL, Balañá M, COOPERA Study Group (2010) Behavioural symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and their association with cognitive impairment. BMC Neurol 10:87

Gaugler JE, Yu F, Krichbaum K, Wyman JF (2009) Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Med Care 47(2):191–198

Asmer MS, Kirkham J, Newton H, Ismail Z, Elbayoumi H, Leung RH et al (2018) Meta-analysis of the prevalence of major depressive disorder among older adults with dementia. J Clin Psychiatry 79(5):17r11772

Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, John V, Loewenstein D (2006) Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63(5):530–538

Curran EM, Loi S (2013) Depression and dementia. Med J Aust 199(S6):S40–S44

Defrancesco M, Marksteiner J, Kemmler G, Fleischhacker WW, Blasko I, Deisenhammer EA (2017) Severity of depression impacts imminent conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 59(4):1439–1448

Novais F, Starkstein S (2015) Phenomenology of depression in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer's Dis 47(4):845–855

Kessing LV, Harhoff M, Andersen PK (2007) Treatment with antidepressants in patients with dementia—a nationwide register-based study. Int Psychogeriatr 19(5):902–913

Orgeta V, Tabet N, Nilforooshan R, Howard R (2017) Efficacy of antidepressants for depression in Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 58(3):725–733

Goodarzi Z, Mele B, Guo S, Hanson H, Jette N, Patten S et al (2016) Guidelines for dementia or Parkinson’s disease with depression or anxiety: a systematic review. BMC Neurol 16(1):244

Mossello E, Boncinelli M, Caleri V, Cavallini MC, Palermo E, Di Bari M et al (2008) Is antidepressant treatment associated with reduced cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease? Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 25(4):372–379

McIntyre RS, Lophaven S, Olsen CK (2014) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of vortioxetine on cognitive function in depressed adults. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 17(10):1557–1567. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1461145714000546

Mahableshwarkar AR, Zajecka J, Jacobson W, Chen Y, Keefe RS (2015) A randomized, placebo-controlled, active-reference, double-blind, flexible-dose study of the efficacy of vortioxetine on cognitive function in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 40(8):2025–2037. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.52

Katona C, Hansen T, Olsen CK (2012) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of LuAA21004 in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 27(4):215–223. https://doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0b013e3283542457

Baune BT, Brignone M, Larsen KG (2018) A network meta-analysis comparing effects of various antidepressant classes on the digit symbol substitution test (DSST) as a measure of cognitive dysfunction in patients with major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 21(2):97–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyx070

Cumbo E, Cumbo S, Torregrossa S, Migliore D (2019) Treatment effects of vortioxetine on cognitive functions in mild Alzheimer’s disease patients with depressive symptoms: a 12 month, open-label, observational study. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 6(3):192–197

Jeong HW, Yoon KH, Lee CH, Moon YS, Kim DH (2022) Vortioxetine treatment for depression in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 20(2):311–319. https://doi.org/10.9758/cpn.2022.20.2.311

Herrmann N, Rabheru K, Wang J, Binder C (2005) Galantamine treatment of problematic behavior in Alzheimer disease: post-hoc analysis of pooled data from three large trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 13(6):527–534

Rösler M, Retz W, Retz-Junginger P, Dennler HJ (1998) Effects of two-year treatment with the cholinesterase inhibitor rivastigmine on behavioural symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Neurol 11(4):211–216

Agüera-Ortiz L, García-Ramos R, Grandas Pérez FJ, López-Álvarez J, Montes Rodríguez JM, Olazarán Rodríguez FJ, Olivera Pueyo J, Pelegrin Valero C, Porta-Etessam J (2021) Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: a Delphi Consensus on etiology, risk factors, and clinical management. Front Psychiatry 12:638651

Gibson C et al (2021) Clinical practice guidelines and principles of care for people with dementia: a protocol for undertaking a Delphi technique to identify the recommendations relevant to primary care nurses in the delivery of person-centred dementia care. BMJ Open 11(5)

Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM et al (2014) Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 67(4):401–409

Spranger J et al (2022) Reporting guidelines for Delphi techniques in health sciences: a methodological review. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 172:1–11

Rapp MA, Schnaider-Beeri M, Purohit DP, Perl DP, Haroutunian V, Sano M (2008) Increased neurofibrillary tangles in patients with Alzheimer disease with comorbid depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 16(2):168–174

Skogseth R, Mulugeta E, Jones E, Ballard C, Rongve A, Nore S et al (2008) Neuropsychiatric correlates of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 25(6):559–563

Finkel SI, Costa e Silva J, Cohen G, Miller S, Sartorius N (1996) Behavioral and psychological signs and symptoms of dementia: a consensus statement on current knowledge and implications for research and treatment. Int Psychogeriatr 8(Suppl 3):497–500

Olin JT, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Schneider LS, Lebowitz BD (2002) Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease: rationale and background. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 10(2):129–141

Cummings JL, Back C (1998) The cholinergic hypothesis of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 6(2 Suppl 1):S64–S78

Verkaik R, Nuyen J, Schellevis F, Francke A (2007) The relationship between severity of Alzheimer’s disease and prevalence of comorbid depressive symptoms and depression: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 22(11):1063–1086

Gainotti G, Marra C (1994) Some aspects of memory disorders clearly distinguish dementia of the Alzheimer’s type from depressive pseudo-dementia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 16(1):65–78

Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Byers AL, McCormick M, Schaefer C, Whitmer RA (2012) Midlife vs late-life depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: differential effects for Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69(5):493–498

Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, Dew MA, Reynolds CF (2013) Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry 202(5):329–335

Beekman AT, Copeland JR, Prince MJ (1999) Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry 174:307–311

Engedal K, Barca ML, Laks J, Selbaek G (2011) Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: specificity of depressive symptoms using three different clinical criteria. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 26(9):944–951

Benoit M, Berrut G, Doussaint J, Bakchine S, Bonin-Guillaume S, Frémont P et al (2012) Apathy and depression in mild Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional study using diagnostic criteria. J Alzheimers Dis 31(2):325–334

Beblo T, Sinnamon G, Baune BT (2011) Specifying the neuropsychology of affective disorders: clinical, demographic and neurobiological factors. Neuropsychol Rev 21(4):337–359

Ismail Z, Elbayoumi H, Fischer CE, Hogan DB, Millikin CP, Schweizer T et al (2017) Prevalence of depression in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 74(1):58–67

Coupland C, Dhiman P, Morriss R, Arthur A, Barton G, Hippisley-Cox J (2011) Antidepressant use and risk of adverse outcomes in older people: population based cohort study. BMJ 343:d4551

Dudas R, Malouf R, McCleery J, Dening T (2018) Antidepressants for treating depression in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8(8):CD003944. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858

APA Work Group on Alzheimer’s Disease and other Dementias, Rabins PV, Blacker D, Rovner BW, Rummans T, Schneider LS et al (2007) American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Am J Psychiatry 164(12 Suppl):5–56

Revet A, Montastruc F, Roussin A, Raynaud JP, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Nguyen TTH (2020) Antidepressants and movement disorders: a postmarketing study in the world pharmacovigilance database. BMC Psychiatry 20(1):308

Overview | Depression in adults: recognition and management | Guidance | NICE [Internet]. NICE; Available on: https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG90. Accessed 10th April 2023

McIntyre RS, Loft H, Christensen MC (2021) Efficacy of vortioxetine on anhedonia: results from a pooled analysis of short-term studies in patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 17:575–585

Mattingly GW, Necking O, Schmidt SN, Reines E, Ren H (2023) Long-term safety and efficacy, including anhedonia, of vortioxetine for major depressive disorder: findings from two open-label studies. Curr Med Res Opin 39(4):613–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2023.2178082

Cumbo E, Adair M, Åstrom DO, Christensen MC (2023) Effectiveness of vortioxetine in patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid Alzheimer’s disease in routine clinical practice: an analysis of a post-marketing surveillance study in South Korea. Front Aging Neurosci 14:1037816. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.1037816

Bishop MM, Fixen DR, Linnebur SA, Pearson SM (2021) Cognitive effects of vortioxetine in older adults: a systematic review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 11:20451253211026796

D’Agostino A, English CD, Rey JA (2015) Vortioxetine (brintellix): a new serotonergic antidepressant. P T Gennaio 40(1):36–40

Sanchez C, Asin KE, Artigas F (2015) Vortioxetine, a novel antidepressant with multimodal activity: review of preclinical and clinical data. Pharmacol Ther Gennaio 145:43–57

Rozzini L, Chilovi BV, Conti M, Bertoletti E, Zanetti M, Trabucchi M et al (2010) Efficacy of SSRIs on cognition of Alzheimer’s disease patients treated with cholinesterase inhibitors. Int Psychogeriatr 22(1):114–119

Gauthier S, Feldman H, Hecker J, Vellas B, Ames D, Subbiah P et al (2002) Efficacy of donepezil on behavioral symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 14(4):389–404

Pákáski M, Bjelik A, Hugyecz M, Kása P, Janka Z, Kálmán J (2005) Imipramine and citalopram facilitate amyloid precursor protein secretion in vitro. Neurochem Int 47(3):190–195

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Ethos srl for logistic support in conducting the Delphi study.

Panelists:

Federica Agosta, Elena Antelmi, Andrea Arighi, Alberto Benussi, Valentina Bessi, Angelo Bianchetti, Stefano Boffelli, Laura Bonanni, Gabriella Bottini, Amalia Cecilia Bruni, Giuseppe Bruno, Paolo Caffarra, Annachiara Cagnin, Stefano Cappa, Anna Rosa Casini, Antonio Cherubini, Alessandra Coin, Rosanna Colao , Laura De Togni, Andrea Fabbo, Carlo Ferrarese, Paolo Forleo, Domenico Fusco, Pietro Gareri, Franco Giubilei, Biancamaria Guarnieri, Alessandro Iavarone, Giuseppe Lanza, Claudio Liguori, Giancarlo Logroscino, Gemma Lombardi, Alba Malara, Alessandra Marcone, Massimiliano Massaia, Patrizia Mecocci, Fiammetta Monacelli, Roberto Monastero, Enrico Mossello, Antonella Notarelli, Lucilla Parnetti, Tommaso Piccoli, Anna Poggesi, Innocenzo Rainero, Elena Salvatore, Elio Scarpini, Michele Zamboni

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Brescia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This Delphi project was promoted by Lundbeck Italia, that did not exert any interference on the definition, analysis, and interpretation of the contents; the preparation of this article was conducted without interference by Lundbeck Italia that financed the work of an independent medical writer and covered the expenses for the open-access publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to formulating the questionnaire, analyzing the responses, and made critical revisions of the manuscript Exploring depression in Alzheimer’s disease: an Italian Delphi Consensus on phenomenology, diagnosis, and management.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed consent statement

Not applicable

Ethical approval

Not required. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

FB has received compensation for consultancy and speaker related activities from Zambon, UCB, Chiesi Pharma, Lundbeck, Sunovion, Bial, SynAgile, Biogen, Kiowa, and Impax. AA has received compensation for consultancy and speaker related activities from UCB, Boehringer Ingelheim, General Electric, Britannia, AbbVie, Kyowa Kirin, Zambon, Bial, Neuroderm, Theravance Biopharma, Roche, and Medscape; he receives research support from Bial, Lundbeck, Roche, Angelini Pharmaceuticals, Horizon 2020—Grant 825785, Horizon2020 Grant 101016902, Ministry of Education University and Research (MIUR) Grant ARS01_01081, and Cariparo Foundation. He serves as consultant for Boehringer–Ingelheim for legal cases on pathological gambling. AF is/has been a consultant and/or a speaker and/or has received research grants from Angelini, Apsen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lundbeck, Janssen, Viatris, Otsuka, Recordati, Sonofi, Aventis, and Sunovion. LFS has received speaker fees from Jazz Pharma, Lundbeck, Angelini, Valeas, Bioprojet, Fidia, and Idorsia and has served on scientific advisory boards for Jazz Pharma, Italfarmaco, Bioprojet, Bayer, and Idorsia. CM received funds from the following companies: Novo-nordisk, Angelini, Lundbeck, Roche, Biogen as consultant in scientific board and congress speaker. PB, GB, SS, and AP declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Padovani, A., Antonini, A., Barone, P. et al. Exploring depression in Alzheimer’s disease: an Italian Delphi Consensus on phenomenology, diagnosis, and management. Neurol Sci 44, 4323–4332 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06891-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06891-w