Abstract

Studies conducted in healthy subjects have clearly shown that different hypnotic susceptibility, which is measured by scales, is associated with different functional equivalence between imagery and perception/action (FE), cortical excitability, and information processing. Of note, physiological differences among individuals with high (highs), medium (mediums), and low hypnotizability scores (lows) have been observed in the ordinary state of consciousness, thus independently from the induction of the hypnotic state, and in the absence of specific suggestions. The potential role of hypnotic assessment and its relevance to neurological diseases have not been fully explored. While current knowledge and therapies allow a better survival rate, there is a constant need to optimize rehabilitation treatments and quality of life. The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of hypnotizability-related features and, specifically, to discuss the hypothesis that the stronger FE, the different mode of information processing, and the greater proneness to control pain and the activity of the immune system observed in individuals with medium-to-high hypnotizability scores have potential applications to neurology. Current evidence of the outcome of treatments based on hypnotic induction and suggestions administration is not consistent, mainly owing to the small sample size in clinical trials and inadequate control groups. We propose that hypnotic assessment may be feasible in clinical routine and give additional cues into the treatment and rehabilitation of neurological diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

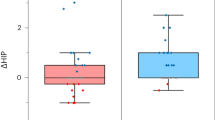

Hypnotizability is a psychophysiological trait predicting the proneness to modify perception, memory, and behavior according to specific suggestions, and to enter the hypnotic state. It is measured by scales [1, 2], is substantially stable through life [3], and is characterized by cerebral and cerebellar morpho-functional peculiarities [4, 5]. The various hypnotizability scores are also associated with different cortical dopaminergic, serotoninergic, and gabaergic tone and oxytocin availability [6]. In the cognitive-emotional domain, high hypnotizability is associated with greater attentional stability/deeper absorption [7], greater fantasy and expectancy proneness, acquiescence and consistency motivation, and emotional intensity [8]. Among the physiological correlates, which are observable also out of hypnosis (that is in the ordinary state of consciousness) and in the absence of specific suggestions, with respect to the persons scoring low on hypnotizability scales (lows), highly hypnotizable individuals (highs) display less close postural and visuomotor control, pre-eminent parasympathetic control of heart rate, less impaired post-occlusion flow-mediated dilation (FMD) of peripheral arteries during mental stress and nociceptive stimulation [2], paradoxical pain control by transcranial anodal stimulation of the cerebellum [9], lower interoceptive accuracy, and greater interoceptive sensitivity 10.

In this scoping review, we propose that hypnotic assessment can assist in the prognosis and treatment of a few neurological diseases. With respect to lows and medium hypnotizables (mediums), in fact, highs display stronger functional equivalence between imagery and perception/action (FE) and different modes of cortical information processing [11, 12], greater excitability of the motor cortex during resting and sensori-motor imagery conditions [13, 14], greater proneness to modulate the activity of the immune system [15,16,17,18,19,20] and peculiar abilities to control pain through imagery, despite the low efficacy of their opioid system [21, 22]. Although highs represent 15% of the entire population [23], mediums often exhibit physiological characteristics intermediate between highs and lows [13, 21], thus being able to take partial advantage from suggestions and hypnotic treatments. Studies aimed at improving their imagery abilities are in progress [24].

Functional equivalence between imagery and perception/action, information processing

The term “functional equivalence” (FE) refers to the similar brain activation occurring during actual and imagined perception/action [25, 26]. As previously mentioned, FE is stronger in highs than in lows [10, 11] and this does not depend on expectation and/or voluntary control. Behavioral investigations, in fact, have revealed that highs display the same earlier component of the vestibulo-spinal reflex when the head is physically rotated toward one side and when this posture is imagined. Since the earlier component of the vestibulospinal reflex is not controlled by expectation and volition, it was hypothesized that brain circuits were similarly activated in the two conditions. This hypothesis was supported by topological analyses of the EEG signals which showed that the global asset of brain activities during actual and imaginatively rotated posture of the head were significantly more similar between each other in highs than in lows [12]. Theoretically, together with the highs’ greater motor cortex excitability [13], these hypnotizability-related characteristics could make highs more prone than the general population to take advantage from imagery training and brain-computer interface (BCI) interventions [27].

Highs and lows differ also in the mode of information processing. Spectral analysis of EEG signals recorded during motor imagery failed to detect significant differences between basal and imagery conditions in highs, in contrast to lows 28. Topological analyses revealed that during sensori-motor imagery lows display significant task-related changes in specific areas, whereas highs exhibit largely distributed, very small changes in their brain activity with respect to resting conditions [12, 28]. In other words, in highs, the cortical representation of both motor action and motor imagery involves smaller changes across larger regions. On this basis, we hypothesize that the highs’ mode of information processing could make them more susceptible than lows’ to recovery after neurological injuries. It has been also shown that hypnotic sessions influence brain plasticity [29], thus theoretically increasing the odd of recovery hypothesized for highs’ owing to their greater FE[12] and to the greater excitability of their motor cortex [13].

Overall, experimental findings obtained in healthy participants suggest that being highly hypnotizable may be a favorable prognostic factor for imagery training aimed at neurorehabilitation. Current literature supports this hypothesis and indicates that imagery training with and without hypnosis is a useful complementary intervention in several movement disorders not only of functional origin [30]. Several studies and meta-analyses, in fact, show that in chronic post-stroke patients mental imagery is more efficacious than standard physical therapy [31], improving gait, balance [32], and motor learning [33]. Moreover, the ability to visualize upper limb mental motor images correlates with post-stroke movement, functionality, and strength, and mental visualization of motor ability correlates with upper limb motor function [34]. Contrasting reports can be due to great heterogeneity between trials in intensity, duration, and studied variables.

In patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) guided imagery increases walking speed and distance, reduces fatigue, improves the quality of life, and positively influences dynamic balance and perceived walking ability [35, 36]. Imagery has also been used to identify and manage emotional aspects of MS possibly associated with symptoms worsening [37] as well as to counteract fatigue and facilitate return-to-work [38]. Fatigue is one of the greatest burdens for people with MS, is present in most of them, and is considered one of the worst symptoms by about half of patients, often disabling and interfering with daily life activity. Different drugs have been proposed to reduce fatigue in patients with MS but have shown poor efficacy. Since MS fatigue has a central origin, with evidence of abnormal cortical activation during voluntary movements [39], imagery training could improve the treatment outcome. Nonetheless, although people with MS have preserved MI ability, impairments in the speed and accuracy of imagery tasks (but, interestingly, not in the vividness of MI) have been found, compared to healthy controls [40]. In this respect, being highs may be greatly helpful [12, 13]. Recently a blinded, randomized trial directed to patients with MS assessed the effects of a telerehabilitation-based motor imagery training (Tele-MIT). Tele-MIT significantly enhanced walking speed, dynamic balance during walking, balance confidence and perceived walking ability, improved quality of life, and reduced fatigue, anxiety, and depression [41]. Studies conducted in small samples and/or patients with low compliance not reporting beneficial effects of MI cannot be considered contrasting with the idea that MI can improve the daily life of patients with MS [42].

In Parkinsonian (PD) patients, motor imagery of gait in gait freezers improved gait velocity, stride length, stance time, swing time, single support time, and total double support time [43]. Dynamic Neuro-Cognitive Imagery (DNI™)—a codified method for imagery training—improved balance, walking, mood, and coordination, and patients felt more physically and mentally active [44]. Autogenic training—which is, like auto-hypnosis, aimed at achieving relaxation—improved PD symptoms [45] as well as cervical dystonia [46].

Also in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) a 4-week hypnosis-based treatment consisting of a hypnosis induction followed by a core phase of guided visual imagery with patient-tailored suggestions and a conclusive phase aiming at self-hypnosis, not only improved wellbeing and quality of life and reduced depression (also in the caregivers), but was even associated with a slower functionality loss at a 6-month follow-up, in a study with fifteen patients compared to fifteen one-to-one matched controls [47].

Immune system

A meta-analysis including 51 studies showed that hypnosis is effective in the control of autoimmune diseases [48]. Derangement of the immune system is found in a few neurological diseases. In MS the immune activity damages the myelin sheath around the axons, causing axonal damage and disruption in the propagation of nerve impulse. In the most frequent form of MS, named “relapsing–remitting MS,” the immune system is intermittently activated by disparate triggers causing exacerbations of the disease. Among various triggers (e.g., infections, post-partum…), psychological stress has been considered both for the onset and for relapse [49]. In this respect, relaxation training, which is more effective in highs [2], can counteract stress effects, and imagery has been used also to manage emotional aspects of MS possibly associated with symptoms worsening [37].

Another chronic neurological autoimmune disorder is myasthenia gravis (MG), in which, in the usual forms, autoantibodies are directed against acetylcholine receptors (AChR) or muscle-specific kinase receptors (MuSK) impairing the proper formation of end-plate potential in the muscle fibers and, thus, muscle contraction. In a recent study, patients affected with MG and a higher level of depression or stress had also a higher level of relapse rate, suggesting that emotional factors may influence the course of MG [50]. Thus, also MG treatment could be integrated by relaxation and imagery training and, theoretically, the outcome could be predicted by hypnotic assessment. The same may be suggested for other, rarer, autoimmune diseases such as nervous system vasculitis, optic neuritis, and neurosarcoidosis, a condition where inflammatory infiltrates are found throughout the nervous system.

Hypnotic treatments may influence the immune system by modulation of the autonomic activity. The highs’ higher parasympathetic tone during relaxation, with respect to lows 2 and their ability to further increase it after hypnotic induction [51] could enable them to improve the activity of the immune system through counteracting the sympathetic inhibition on humoral and cell immunity. Highs are expected to be more prone than lows and mediums to take advantage from positive/pleasant/relaxing imagery [2], inducing changes in the immune activity owing to their peculiar imagery abilities, i.e., stronger FE and deeper absorption in mental activities [7]. After imagery and relaxation training, indeed, highs show greater decreases than lows in the activity of Natural Killers lymphocytes and lymphocyte proliferative response [15, 16, 20]. Gruzelier et al. [52] showed that 10 sessions of hypnosis buffer the decline in NKP, CD8, and CD8/CD4 ratio occurring in students during examination sessions and increase cortisol levels. Also, effects on B-cells and helper T cells have been reported [16, 17] together with upregulation of the expression of immune-related genes in lymphocytes by hypnosis [18]. More recently, autogenic training increased the IgA levels in patients undergoing surgery for breast cancer [19]. In geriatric patients, autosuggestions improved quality of life, increased serum cortisol and interleukin-6 in geriatric patients who displayed also tendency to increase interleukin-2, interferon-γ, and N-acetylaspartate/creatine ratio in the prefrontal cortex [53].

In brief, a multidisciplinary approach including suggestions for relaxation, pleasant experiences, and/or motor imagery may improve the treatment outcome, which could be predicted by hypnotic assessment.

Pain control: suggestions for analgesia or motor imagery, drugs selection

Suggestions for analgesia and/or pleasant imagery reduce pain whichever the pain origin and duration [54,55,56]. They can be personalized (for instance, “experiencing wellness and fitness on a green grass carpet while trees swing and the wind caresses the face,” or “lying on warm sand while listening to the see,” or “relaxing on a soft snow carpet looking at mountains”) and can refer or not to pain. In the latter case, for instance, the patients can be invited to imagine that “her/his pain leaves the abdomen and flies on clouds which become darker and darker,” or “to imagine that a particular glove prevents any unpleasant information related to the painful body part to reach the brain, as if nerves has been cut”). Of note, suggestions are effective also out of the hypnotic state, thus being available to clinicians in every situation [21, 22]. Moreover, there is a large amount of experimental evidence indicating that suggestions reduce pain not only in highs, but in the general population [21, 22], although through specific hypnotisability-related mechanisms in highs, suggestions-induced placebo in lows, and possibly mixed mechanisms in mediums. An important difference, in this respect, is that the highs’ response to the suggestions for analgesia does not involve the release of endogenous opioids, whereas placebo-related analgesia depends on opioids [21, 22].

Suggestions for analgesia and self-hypnosis have been efficaciously used to reduce pain in post-stroke patients, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Parkinson’s disease, Guillain-Barré syndrome, HIV, post-polio syndrome, diabetes, and cancer [57]. Moreover, hypnotic treatment improved the efficacy of self-hypnosis in MS patients [58], led to a reduction of about 90% in the median number of migraine attacks, and outperformed standard prophylactic treatment with prochlorperazine [59], even in juvenile migraine, where self-hypnosis was superior to propranolol and placebo in reducing headache frequency [60]. In patients with chronic tension headache, hypnotherapy reduced the number of headache days, the number of headache hours, headache intensity, and anxiety scores [61]. In both migraine and tension headache patients’, hypnosis and placebo induced similar improvements and patients reduced their medication usage. Of note, hypnosis has been effective in reducing migraine symptoms even in people with low susceptibility to hypnosis [62], which is likely due to placebo-related mechanisms induced by suggestions in mediums and lows [21, 22]. These studies did not show any difference between one and four hypnotic sessions indicating that even a short treatment may be effective.

In the general population, both physical stimulation and motor imagery (MI) are used to control pain, in line with the concept of functional equivalence between imagery and perceptions (see the “Functional equivalence between imagery and perception/action, information processing” section). MI, in fact, produces functional cerebral reorganization similar to those obtained by physical practice [63] and may reverse, at least partially, the alterations in the body schema observed in neuropathic pain and pain perception. In highs, the effects of motor imagery are expected to be stronger than in the general population owing to their stronger functional equivalence between imagery and perception/action [12] and to their greater proneness to neural plasticity after hypnotic treatments [29]. For instance, pain intensity associated with spinal injuries (SCI) and associated with a reorganization of the SI could be efficaciously treated by suggestions of analgesia as well as by motor imagery training and the outcome should be better in highs[64]. The same can be hypothesized for phantom limb pain (PLP)[65] and complex regional pain syndrome type 1 (CRPS1) [66], associated with a maladaptive neuronal plasticity not limited to SI, but extended to the dorsal ganglion [67].

A specific motor imagery protocol—graded motor imagery (GMI) consisting of three sequential phases (identifying whether pictures of part of the body depict the left or right side, imagining own movements, and performing movements of the unaffected side of the body)—has been used in several patients. A non-randomized controlled trial on twenty-eight patients with first-ever stroke [68] treated with twenty sessions of one hour each of GMI or conventional rehabilitation, showed that patients on GMI had better scores over the control group in the pain section of Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA), a stroke-specific index designed to assess motor functioning and sensation in patients with post-stroke hemiplegia. In patients with CRPS1 and PLP, a short GMI training reduced pain up to six months after the end of the program, improved function, and, limitedly to CRSP1 patients, reduced swelling compared to standard treatment [69,70,71]. Interestingly, intensive 6-week training in MI, either once a week or once a fortnight, consisting of “body scan” exercise and imagination of movements and sensations in the phantom limb, reduced cortical reorganization and pain in PLP patients. Of note, patients who undertook the three stages in different orders did not respond, suggesting that the effect of GMI is dependent from a specific, sequential activation of a variety of cortical networks[70]. In contrast, another multicentred study aimed at using GMI in clinical practice which included both CRPS type 1 and 2 (patients with evidence of nerve injury) failed to show any significant improvement in pain [72].

In tetraplegic patients, a modified GMI protocol [73] induced a significant pain reduction, on the numeric rating scale of pain and on visual analog scale of pain, for the mean total score at the Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory and for its subsections assessing dysesthesia, paraesthesia, allodynia, and pressor pain. Moreover, after MI intervention, patients reported better sleep and less interference of pain on sleep compared to the control group. In brief, suggestions for analgesia and pleasant imagery as well as motor imagery are useful tools for pain control. Nonetheless, Gustin et al. found that, in a cohort of SCI patients, imaging movements of ankle plantar and dorsiflexion increased pain in patients who suffered from below-level neuropathic pain and might even induce unpleasant sensations in those who were otherwise symptom free [74]. The authors suggest that this unexpected finding may be due to increased sodium channel expression or inhibitory dysfunction at the lesion level.

In brief, suggestions for analgesia and pleasant imagery as well as motor imagery are useful tools for pain control.

Finally, we must underline that the pharmacological treatments of acute/chronic pain can be oriented by hypnotic assessment. Highs, in fact, exhibit the µ1 polymorphism (A118G, rs1799971) associated with low sensitivity to opiates [21, 22]. Such polymorphism requires higher opiate dosages and makes highs more sensitive to side opiate effects than prone to the experience of analgesia. Thus, hypnotic assessment in pain patients is useful to orient pharmacological therapies.

Limitations and conclusions

Imagery abilities such as the strength of the functional equivalence between imagery and perception/action, the proneness to control the immune system through relaxation by enhancing the parasympathetic tone, to reduce pain through cognitive strategies, and to take advantage from certain pharmacological pain, can be predicted by hypnotic assessment. Suggestions with and without induction of hypnosis also allow an improvement of the patients’ quality of life including physical symptoms and disease progression. Thus, we propose hypnotic assessment as a routine evaluation of neurological patients.

A limitation of the role of hypnotic assessment could be the fact that highs and lows represent 15% of the population each, while mediums represent its largest part [23]. Nonetheless, mediums often exhibit physiological characteristics intermediate between highs and lows [13, 21], thus being able to take partial advantage from suggestions and hypnotic treatments. Clinical studies should be conducted according to the recent guidelines for hypnosis research, which suggest to include mediums and explore both wake and hypnotic conditions with and without suggestions [75].

In conclusion, our opinion is that novel approaches to neurological patients suffering from sensory, motor, and cognitive symptoms of various origins should consider also hypnotizability among the classical psychophysiological traits potentially influencing symptoms and recovery and usually investigated in the context of the body-mind interaction.

Change history

22 August 2022

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

References

Elkins GR, Barabasz AF, Council JR, Spiegel D (2015) Advancing research and practice: The revised APA division 30 definition of hypnosis. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 63(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2014.961870

Santarcangelo EL, Scattina E (2016) Complementing the Latest APA Definition of Hypnosis: Sensory-Motor and Vascular Peculiarities Involved in Hypnotizability. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 64(3):318–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2016.1171093

Piccione C, Hilgard ER, Zimbardo PG (1989) On the degree of stability of measured hypnotizability over a 25-year period. J Pers Soc Psychol 56(2):289–295. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.289

Landry M, Lifshitz M, Raz A (2017) Brain correlates of hypnosis: A systematic review and meta-analytic exploration. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 81:75–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.020

Picerni E, Santarcangelo EL, Laricchiuta D et al (2019) Cerebellar Structural Variations in Subjects with Different Hypnotizability. Cerebellum 18(1):109–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-018-0965-y

Acunzo DJ, Oakley DA, Terhune DB (2021) The neurochemistry of hypnotic suggestion. Am J Clin Hypn 63(4):355–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2020.1865869

Raz A (2005) Attention and hypnosis: neural substrates and genetic associations of two converging processes. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 53(3):237–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207140590961295

Council JR, Green JP (2004) Examining the absorption-hypnotizability link: the roles of acquiescence and consistency motivation. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 52(4):364–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207140490883950

Bocci T, Barloscio D, Parenti L, Sartucci F, Carli G, Santarcangelo EL (2017) High Hypnotizability Impairs the Cerebellar Control of Pain. Cerebellum 16(1):55–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-016-0764-2

Rosati A, Belcari I, Santarcangelo EL, Sebastiani L (2021) Interoceptive Accuracy as a Function of Hypnotizability. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 69(4):441–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2021.1954859

Ruggirello S, Campioni L, Piermanni S, Sebastiani L, Santarcangelo EL (2019) Does hypnotic assessment predict the functional equivalence between motor imagery and action? Brain Cogn 136:103598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2019.103598

Ibáñez-Marcelo E, Campioni L, Phinyomark A, Petri G, Santarcangelo EL (2019) Topology highlights mesoscopic functional equivalence between imagery and perception: The case of hypnotizability. Neuroimage 200:437–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.044

Spina V, Chisari C, Santarcangelo EL (2020) High Motor Cortex Excitability in Highly Hypnotizable Individuals: A Favourable Factor for Neuroplasticity? Neuroscience 430:125–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.01.042

Cesari P, Modenese M, Benedetti S, EmadiAndani M, Fiorio M (2020) Hypnosis-induced modulation of corticospinal excitability during motor imagery. Sci Rep 10(1):16882. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74020-0

Zachariae R, Hansen JB, Andersen M et al (1994) Changes in cellular immune function after immune specific guided imagery and relaxation in high and low hypnotizable healthy subjects. Psychother Psychosom 61(1–2):74–92. https://doi.org/10.1159/000288872

Ruzyla-Smith P, Barabasz A, Barabasz M, Warner D (1995) Effects of hypnosis on the immune response: B-cells, T-cells, helper and suppressor cells. Am J Clin Hypn 38(2):71–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.1995.10403185

Wood GJ, Bughi S, Morrison J, Tanavoli S, Tanavoli S, Zadeh HH (2003) Hypnosis, differential expression of cytokines by T-cell subsets, and the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Am J Clin Hypn 45(3):179–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2003.10403525

Kovács ZA, Puskás LG, Juhász A et al (2008) Hypnosis upregulates the expression of immune-related genes in lymphocytes. Psychother Psychosom 77(4):257–259. https://doi.org/10.1159/000128165

Minowa C, Koitabashi K (2014) The effect of autogenic training on salivary immunoglobulin A in surgical patients with breast cancer: a randomized pilot trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract 20(4):193–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2014.07.001

Gruzelier JH (2002) A review of the impact of hypnosis, relaxation, guided imagery and individual differences on aspects of immunity and health. Stress 5(2):147–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890290027877

Santarcangelo EL, Consoli S (2018) Complex role of hypnotizability in the cognitive control of pain. Front Psychol 9(NOV). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02272

Santarcangelo EL, Carli G (2021) Individual Traits and Pain Treatment: The Case of Hypnotizability. Front Neurosci 15:683045. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.683045

De Pascalis V, Bellusci A, Russo PM (2000) Italian norms for the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale, Form C. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 48(3):315–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207140008415249

Kaczmarska AD, Jęda P, Guśtak E, Mielimąka M, Rutkowski K (2020) Potential Effect of Repetitive Hypnotic Inductions on Subjectively Rated Hypnotizability: A Brief Report. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 68(3):400–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2020.1747939

Marc J (1994) The representing brain: Neural correlates of motor intention and imagery. Behav Brain Sci 1994(17):187–245

Kosslyn SM, Thompson WL, Klm IJ, Alpert NM (1995) Topographical representations of mental images in primary visual cortex. Nature 378(6556):496–498. https://doi.org/10.1038/378496a0

Palumbo A, Gramigna V, Calabrese B, Ielpo N. Motor-Imagery EEG-Based BCIs in Wheelchair Movement and Control: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors (Basel) 2021;21(18). https://doi.org/10.3390/s21186285

Ibáñez-Marcelo E, Campioni L, Manzoni D, Santarcangelo EL, Petri G. (2019) Spectral and topological analyses of the cortical representation of the head position: Does hypnotizability matter? Brain Behav 9(6). https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1277

Halsband U, Gerhard WT (2019) Functional Changes in Brain Activity After Hypnosis: Neurobiological Mechanisms and Application to Patients with a Specific Phobia—Limitations and Future Directions. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 67(4):449–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2019.1650551

Garcin B (2018) Motor functional neurological disorders: An update. Rev Neurol (Paris) 174(4):203–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2017.11.003

López ND, Monge Pereira E, Centeno EJ, Miangolarra Page JC (2019) Motor imagery as a complementary technique for functional recovery after stroke: a systematic review. Top Stroke Rehabil 26(8):576–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2019.1640000

Kalra L, Dobkin BH (2021) Facilitating mental imagery to improve mobility after stroke: All in the head. Neurol 96(21):975–976. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000011993

Gregor S, Saumur TM, Crosby LD, Powers J, Patterson KK (2021) Study paradigms and principles onvestigated in motor learning research after stroke: A scoping review. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl 3(2):100111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arrct.2021.100111

Poveda-García A, Moret-Tatay C, Gómez-Martínez M (2021) The association between mental motor imagery and real movement in stroke. Healthc 9(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9111568

Case LK, Jackson P, Kinkel R, Mills PJ (2018) Guided imagery improves mood, fatigue, and quality of life in individuals with multiple sclerosis: An exploratory efficacy trial of healing light guided imagery. J Evid Based Integr Med 23:2515690X17748744. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515690X17748744

Gil-Bermejo-Bernardez-Zerpa A, Moral-Munoz JA, Lucena-Anton D, Luque-Moreno C (2021) Effectiveness of motor imagery on motor recovery in patients with multiple sclerosis: Systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020498

Brambila-Tapia AJL, Gutiérrez-García MM, Ruiz-Sandoval JL et al (2022) Using hypnoanalysis and guided imagery to identify and manage emotional aspects of multiple sclerosis. Explore (NY) 18(1):88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2020.10.002

Agostini F, Pezzi L, Paoloni M et al (2021) Motor imagery: A resource in the fatigue rehabilitation for return-to-work in multiple sclerosis patients-a mini systematic review. Front Neurol 12:696276. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.696276

Filippi M, Rocca MA, Colombo B et al (2002) Functional magnetic resonance imaging correlates of fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage 15(3):559–567. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2001.1011

Tabrizi YM, Mazhari S, Nazari MA, Zangiabadi N, Sheibani V (2014) Abnormalities of motor imagery and relationship with depressive symptoms in mildly disabling relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Phys Ther 38(2):111–118. https://doi.org/10.1097/NPT.0000000000000033

Kahraman T, Savci S, Ozdogar AT, Gedik Z, Idiman E (2020) Physical, cognitive and psychosocial effects of telerehabilitation-based motor imagery training in people with multiple sclerosis: A randomized controlled pilot trial. J Telemed Telecare 26(5):251–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X18822355

Bovend’Eerdt TJH, Dawes H, Sackley C, Izadi H, Wade DT (2009) Mental techniques during manual stretching in spasticity - A pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 23(2):137–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508097298

Huang H-C, Chen C-M, Lu M-K et al (2021) Gait-related brain activation during motor imagery of complex and simple ambulation in parkinson’s disease with freezing of gait. Front Aging Neurosci 13:731332. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.731332

Abraham A, Hart A, Andrade I, Hackney ME (2018) Dynamic neuro-cognitive imagery improves mental imagery ability, disease severity, and motor and cognitive functions in people with Parkinson’s disease. Bisio A, ed. Neural Plast 2018:6168507. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6168507

Ajimsha MS, Majeed NA, Chinnavan E, Thulasyammal RP (2014) Effectiveness of autogenic training in improving motor performances in Parkinson’s disease. Complement Ther Med 22(3):419–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2014.03.013

Isabel Useros-Olmo PT, AP, Martínez-Pernía D, Huepe DP (2020) The effects of a relaxation program featuring aquatic therapy and autogenic training among people with cervical dystonia (a pilot study). Physiother Theory Pract 36(4):488–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2018.1488319

Kleinbub JR, Palmieri A, Broggio A et al (2015) Hypnosis-based psychodynamic treatment in ALS: a longitudinal study on patients and their caregivers. Front Psychol 6:822. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00822

Torem MS (2007) Mind-body hypnotic imagery in the treatment of auto-immune disorders. Am J Clin Hypn 50(2):157–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2007.10401612

Artemiadis AK, Anagnostouli MC, Alexopoulos EC (2011) Stress as a risk factor for multiple sclerosis onset or relapse: A systematic review. Neuroepidemiology 36(2):109–120. https://doi.org/10.1159/000323953

Bogdan A, Barnett C, Ali A et al (2020) Prospective study of stress, depression and personality in myasthenia gravis relapses. BMC Neurol 20(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-020-01802-4

DeBenedittis G, Cigada M, Bianchi A, Signorini MG, Cerutti S (1994) Autonomic changes during hypnosis: a heart rate variability power spectrum analysis as a marker of sympatho-vagal balance. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 42(2):140–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207149408409347

Gruzelier J, Smith F, Nagy A, Henderson D (2001) Cellular and humoral immunity, mood and exam stress: the influences of self-hypnosis and personality predictors. Int J Psychophysiol Off J Int Organ Psychophysiol 42(1):55–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8760(01)00136-2

Sari NK, Setiati S, Taher A et al (2017) The role of autosuggestion in geriatric patients’ quality of life: a study on psycho-neuro-endocrine-immunology pathway. Soc Neurosci 12(5):551–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2016.1196243

Thompson T, Terhune DB, Oram C et al (2019) The effectiveness of hypnosis for pain relief: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 85 controlled experimental trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 99:298–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.02.013

Milling LS, Valentine KE, LoStimolo LM, Nett AM, McCarley HS (2021) Hypnosis and the Alleviation of Clinical Pain: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 69(3):297–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2021.1920330

Bicego A, Rousseaux F, Faymonville M-E, Nyssen A-S, Vanhaudenhuyse A (2022) Neurophysiology of hypnosis in chronic pain: A review of recent literature. Am J Clin Hypn 64(1):62–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2020.1869517

Castelnuovo G, Giusti EM, Manzoni GM et al (2016) Psychological Treatments and Psychotherapies in the Neurorehabilitation of Pain Evidences and Recommendations from the Italian Consensus Conference on Pain in Neurorehabilitation. Front Psychol 7:115. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00115

Hosseinzadegan F, Radfar M, Shafiee-Kandjani AR, Sheikh N (2017) Efficacy of Self-Hypnosis in Pain Management in Female Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 65(1):86–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2017.1246878

Anderson JAD, Basker MA, Dalton R (1975) Migraine and hypnotherapy. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 23(1):48–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207147508416172

Olness K, MacDonald JT, Uden DL (1987) Comparison of self-hypnosis and propranolol in the treatment of juvenile classic migraine. Pediatrics 79(4):593–597

Melis PM, Rooimans W, Spierings EL, Hoogduin CA (1991) Treatment of chronic tension-type headache with hypnotherapy: a single-blind time controlled study. Headache 31(10):686–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.1991.hed3110686.x

Friedman H, Taub HA (1984) Brief Psychological Training Procedures in Migraine Treatment. Am J Clin Hypn 26(3):187–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.1984.10404162

Jackson PL, Lafleur MF, Malouin F, Richards CL, Doyon J (2003) Functional cerebral reorganization following motor sequence learning through mental practice with motor imagery. Neuroimage 20(2):1171–1180. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00369-0

Wrigley PJ, Press SR, Gustin SM et al (2009) Neuropathic pain and primary somatosensory cortex reorganization following spinal cord injury. Pain 141(1–2):52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2008.10.007

Flor H, Elbert T, Knecht S et al (1995) Phantom-limb pain as a perceptual correlate of cortical reorganization following arm amputation. Nature 375(6531):482–484. https://doi.org/10.1038/375482a0

Maihöfner C, Handwerker HO, Neundörfer B, Birklein F (2003) Patterns of cortical reorganization in complex regional pain syndrome. Neurology 61(12):1707–1715. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000098939.02752.8E

Kajander KC, Wakisaka S, Bennett GJ (1992) Spontaneous discharge originates in the dorsal root ganglion at the onset of a painful peripheral neuropathy in the rat. Neurosci Lett 138(2):225–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3940(92)90920-3

Polli A, Moseley GL, Gioia E et al (2017) Graded motor imagery for patients with stroke: A non-randomized controlled trial of a new approach. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 53(1):14–23. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.16.04215-5

Moseley GL (2006) Graded motor imagery for pathologic pain: A randomized controlled trial. Neurology 67(12):2129–2134. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000249112.56935.32

Moseley GL (2005) Is successful rehabilitation of complex regional pain syndrome due to sustained attention to the affected limb? A randomised clinical trial Pain 114(1–2):54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.024

MacIver K, Lloyd DM, Kelly S, Roberts N, Nurmikko T (2008) Phantom limb pain, cortical reorganization and the therapeutic effect of mental imagery. Brain 131(8):2181–2191. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awn124

Johnson S, Hall J, Barnett S et al (2012) Using graded motor imagery for complex regional pain syndrome in clinical practice: failure to improve pain. Eur J Pain 16(4):550–561. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1532-2149.2011.00064.x

Kaur J, Ghosh S, Sahani AK, Sinha JK (2020) Mental Imagery as a Rehabilitative Therapy for Neuropathic Pain in People With Spinal Cord Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 34(11):1038–1049. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968320962498

Gustin SM, Wrigley PJ, Gandevia SC, Middleton JW, Henderson LA, Siddall PJ (2008) Movement imagery increases pain in people with neuropathic pain following complete thoracic spinal cord injury. Pain 137(2):237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.032

Jensen MP, Jamieson GA, Lutz A et al (2017) New directions in hypnosis research: strategies for advancing the cognitive and clinical neuroscience of hypnosis. Neurosci Conscious 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/nc/nix004

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università di Pisa within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

None.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fontanelli, L., Spina, V., Chisari, C. et al. Is hypnotic assessment relevant to neurology?. Neurol Sci 43, 4655–4661 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06122-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06122-8