Abstract

Background and aim

Peginterferon beta-1a (Plegridy) offers the advantage of a prolonged half-life with less-frequent administration and a higher patient adherence. However, the use of an interferon may lead to flu-like symptoms (FLS) and injection-site reactions (ISR) that results in drug discontinuation. The objective of this Delphi analysis was to obtain consensus on the characteristics and management of FLS/ISR of peginterferon beta-1a in patients with relapsing-remitting MS based on real-world clinical experiences.4

Methods

A steering committee of MS neurologists and nurses identified issues regarding the features and management of adverse events and generated a questionnaire used to conduct three rounds of the Delphi web survey with an Italian expert panel (54 neurologists and nurses).

Results

Fifty-three (100%), fifty-one (96.22%), and forty-two (79.24%) responders completed questionnaires 1, 2, and 3 respectively. Responders reported that, during the first 6 months of treatment, FLS generally occurred 6–12 h after injection; the fever tended to resolve after 12–24 h; otherwise, FLS lasted up to 48 h. FLS improved or disappeared after 6 months of treatment in most cases. Paracetamol was recommended as the first choice for managing FLS. Erythema was the most common ISR and usually resolved within 1 week after injection. Responders reported that the adherence to treatment increases after adequate patient education on the drug’s tolerability profile.

Conclusions

Patient education and counseling play a key role in promoting adherence to treatment especially in the first months also in patients switching from nonpegylated IFNs to peginterferon beta-1a.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Compliance and adverse events are a major issue in treating chronic disease such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and multiple sclerosis (MS) [1,2,3]. It has been estimated that about 50% of patients do not adhere to their therapy for chronic conditions [4].

First-line injectable disease-modifying therapies (DMT) for MS require frequently administration and sometimes are not so well accepted by the patients. Thus, when considering the efficacy of MS treatment efficacy of MS treatment, the clinicians have to take into account the risk of negative clinical outcome due to poor adherence. Several studies have shown that 13–30% of MS patients discontinued therapy [3, 5, 6].

Main reasons for poor patient adherence to interferon (IFN) beta treatment include frequency of administration and adverse events (AE) such as flu-like symptoms (FLS) and injection-site reactions (ISR) [7, 8].

The formulation of peginterferon beta-1a (Plegridy) approved for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS has a prolonged half-life and offers the advantage of a less-frequent administration (a subcutaneous dose of 125 mcg every 2 weeks) with a higher patient adherence [9]. The efficacy of peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks was demonstrated in the phase III ADVANCE study with greater effect on annualized relapse rate, sustained disability progression, and magnetic resonance endpoints (new or enlarging T2 lesions and gadolinium-enhanced lesions) than peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks and placebo. The safety profile of peginterferon beta-1a over the second year of treatment was similar to that observed during the first year [10, 11].

AE associated with peginterferon beta-1a administration were consistent with the widely known profiles of other IFN beta formulations. The most common AEs were ISR and FLS but they were less frequent compared to other IFNs due to a significant reduction in the number of injections [12].

The aim of this survey was to obtain consensus on the characteristics and management of peginterferon beta-1a (Plegridy)-related FLS/ISR in patients with relapsing-remitting MS based on neurologists’ and nurses’ clinical experience at 20 Italian centers.

Material and methods

An independent steering committee of three Italian neurologists and three nurses with several years of experience in treatment of MS identified issues surrounding the management of AE and generated the content for a 19-item questionnaire. An open-ended question (item 20) was used to explore pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for ISR.

This questionnaire was used to conduct a Delphi web survey with an expert panel (30 MS neurologists and 23 nurses) from 20 Italian MS centers. The panel was mainly made of clinicians from public Hospitals (only 5 neurologists were from University centers) with an average of 12 years in MS practice. The neurologists were coming from almost every region of Italy. Nurses were less than clinicians because in some centers nurse MS service was absent. The sample size cannot be calculated because of the exploratory nature of this research.

The Delphi technique is suggested to be an effective way to gain and measure group consensus in healthcare consensus development methods [13]. It is an anonymous structured approach, in which information is gathered from a group of participants through a number of rounds [14]. Anonymity can reduce the inhibition normally occurring in decision-making as individuals will be more open with their answers.

Three consensus rounds were executed over nearly 5 months (from June 2018 to October 2018). After the 2nd Round, the Board decided to modify item 11 with a new statement 11bis to better clarify the issue.

All responses were aggregated to maintain responder anonymity. Review and approval of this study by an ethics committee were not necessary since patient information was not obtained and all the data were regarding clinician opinion.

In each round, participants were invited to respond by scaling each statement on degree of agreement (1 = no agreement to 7 = maximum agreement).

The “interquartile interval” (IQR) was used to measure the deviation of the opinion of an expert from the opinion of the whole panel (median value). The IQR is the difference between the 3rd and 1st quartiles in which the middle 50% of the provided evaluations were located.

Consensus was defined as > 74% agreement. For all 19 questions, the following statistical parameters were calculated: 1st and 3rd quartile and interquartile range.

Results

Responses were obtained from 53 (100%) experts in the first round and 51 (96.22%) and 42 (79.24%) experts in the second and third rounds, respectively. The agreement between nurses and neurologists for individual items was not significantly different from agreement between neurologists.

The expert panel showed a high level of agreement in the 3 rounds. The comparative analysis showed no differences between neurologists and nurses. In the most cases, the median values of the 20 statements were similar as shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4.

All statements are presented in Table 1.

High consensus was achieved on 16 statements and 4 statements reached a negative consensus (items 5, 9, 11 and 14).

Responders stated that, during the first 6 months of treatment, patients generally experienced FLS 6–12 h after injection (Fig. 1). The fever tended to resolve after 12–24 h; otherwise, FLS lasted up to 48 h. These symptoms improved or disappeared after 6 months of treatment in most cases.

All experts indicated that, during the first 6 months of treatment, the main reason for discontinuing peginterferon beta-1a was FLS which had a moderate effect on activities of daily living; however, all agreed that the frequency and severity of FLS decreased over time. During the first 6 months of treatment, fever was usually higher than 37.5 °C but lasted shorter (12–24 h) than the other flu-like symptoms.

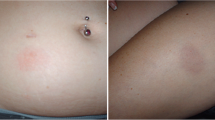

The most frequent ISR reported during the treatment of peginterferon beta-1a was erythema. This reaction usually resolved within 1 week after injection. Respondents agreed that impact of ISR depended on the frequency of injectable DMD administration and usually was not substantial.

Responders stated that patients experiencing IRS discontinued drug mainly due to cosmetic issue of redness.

Severity and duration of erythema, pain, and induration depended on injection site.

Consensus was achieved on the use of certain prophylactic therapy to prevent or manage FLS. Paracetamol was recommended as the first choice; other pharmacologic therapies such as naproxen sodium or ibuprofen were used as second choice.

It was agreed that some local symptomatic therapies (corticosteroids, vitamin K, antihistamines) were able to improve ISR. Non-pharmacological interventions included altering or cooling of the injection site and several local natural treatments such as Aloe vera gel, arnica gel, Calendula officinalis cream, and other emollient oils (Table 2)

The panelists agreed that educating patients about the characteristics and management of FLS and ISR was a critical issue because FLS and ISR were characterized by high inter-patient variability.

All patients beginning treatment should receive education that includes information about the frequency, severity, and management of FLS and ISR. This approach should be considered in treatment of naïve patients and patients switching from other IFNs to peginterferon beta-1a. Empowering patients through correct information on care management was considered essential to improve treatment adherence.

Consensus was not reached for 1 statement on FLS (item 5: During the first 6 months of treatment, fever was usually lower than 37.5 °C) and 3 statements regarding ISR. The experts did not agree that patients manifested IRS after every dose administration without improving over time. Nurses and neurologists appeared to be in disagreement about considering ISR as the main factor responsible of drug discontinuation. Moreover, there was no agreement that ISR did not impact patients’ quality of life.

Discussion

The objective of this Delphi analysis was to obtain consensus on the characteristics and management of FLS and ISR of peginterferon beta-1a in patients with relapsing-remitting MS based on Italian real-world clinical experiences. In summary, all the statements achieved a consensus in the survey. There was positive consensus on 16 statements and negative consensus on 4 statements.

Adherence to therapy is a critical issue to improving long-term outcomes in MS patients and long-term adherence rates for MS treatment rarely exceed 75% [7].

The use of subcutaneous IFNs can be accompanied by FLS and ISR leading to an impaired treatment adherence and to early dropouts. Thus, management of side effects is essential to maintain treatment and prevent disease progression [15, 16].

Two previous studies have described the characteristics and management of FLS and/or ISR in patients with relapsing-remitting MS based on neurologist experiences from the randomized, phase III studies of peginterferon beta-1a (ADVANCE and ALLOW) [17,18,19].

The survey on the ADVANCE study obtained consensus on the characteristics and management of FLS and ISR for patients with relapsing-remitting MS treating with peginterferon beta-1a, while the Delphi panel on the ALLOW study discussed the management of ISR for patients with relapsing-remitting MS switching from nonpegylated IFNs to peginterferon beta-1a.

To our knowledge, this is the first survey based on a panel of experts (neurologists and nurses) who have tried to obtain consensus on the characteristics and management of peginterferon beta-1a (Plegridy)-related FLS/ISR in patients with relapsing-remitting MS, based on real-world clinical experiences.

In contrast to the ADVANCE survey, we described a more delayed onset of FLS (6 to 12 h after injection compared to 1 to 8 h after dosing) with a longer duration (up 48 h vs 24 h).

This delayed onset of FLS confirms data from the ALLOW study (median time to FLS onset 10.4 h) (19) in which, however, the FLS duration was shorter than that in our survey. As shown by Halper et al, the reported of a FLS lasting 48 to 72 h may subtend the error to classify a FLS beginning in the evening of day 1 and lasting until the evening of day 2 has 48 h of duration instead of 24 (17). Frequency and duration of these AE generally reduced after 6 months of treatment according to the Delphi responders in the ADVANCE survey.

The use of prophylactic therapy to prevent or manage FLS was widely recommend as mentioned in the product labels for IFN beta therapies currently approved for the treatment of MS.

Although no significant difference was found between different treatment options (paracetamol, ibuprofen, and steroid prednisone) on FLS [20,21,22], paracetamol has been confirmed as the first choice in real-life experiences.

We confirmed that the most frequent ISR reported during the treatment of peginterferon beta-1a was erythema. As highlighted in the other two surveys, the duration of erythema was longer than described with other IFN therapies (resolution within 1 week after injection) but its impact on patients’ daily activities was mild.

Several non-pharmacological strategies were considered helpful in minimizing ISR in particular local natural treatments such as Aloe vera gel, arnica gel, Calendula officinalis cream, and other emollient oils.

Because FLS and ISR most often occur during therapy initiation, it is critical that patients be counseled on both the probability of symptoms and their management.

Results from this Delphi panel suggest that all patients beginning peginterferon beta-1a treatment should receive education that includes information about the frequency, severity, and management of FLS and ISR. This approach should be considered also in patients switching from other IFNs to peginterferon beta-1a.

Counseling and education have been shown to be a key point of patient care, as adherence rates are higher in patients with realistic expectations of treatment-related side effects [23, 24].

This study had some weaknesses related to the use of the Delphi technique. In particular, judgments are those of a selected group of neurologists and nurses from some Italian centers and may not be representative of practice in other countries or considered guidelines. However, the strength of our study includes access to real-world data, which improves the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusions

This study is the first study to provide a convergence of opinions between neurologist and nurses on FLS and ISR based on real-world experience in patients treated with pegylated interferon beta-1a.

The agreement obtained on FLS and ISR management is consistent with previously published recommendations suggesting that patient education and counseling play a key role in promoting adherence to treatment, especially in the first months, also in patients switching from nonpegylated IFNs to peginterferon beta-1a.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (CC) upon reasonable request.

Change history

22 January 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-021-05083-8

References

Polonsky WH, Henry RR (2016) Poor medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: recognizing the scope of the problem and its key contributors. Patient Prefer Adherence 10:1299–1307

Jung O, Gechter JL, Wunder C, Paulke A, Bartel C, Geiger H, Toennes SW (2013) Resistant hypertension? Assessment of adherence by toxicological urine analysis. J Hypertens 31:766–774

Klauer T, Zettl UK (2008) Compliance, adherence, and the treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 255(Suppl 6):87–92

Sabate E (2003) Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. World Health Organization, Switzerland

Hutchinson M (2005) Treatment adherence: what is the best that can be achieved? Int MS J 12:73

Treadaway K, Cutter G, Salter A, Lynch S, Simsarian J, Corboy J, Jeffery D, Cohen B, Mankowski K, Guarnaccia J, Schaeffer L, Kanter R, Brandes D, Kaufman C, Duncan D, Marder E, Allen A, Harney J, Cooper J, Woo D, Stüve O, Racke M, Frohman EM (2009) Factors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MS. J Neurol 256:568–576

Steinberg SC, Faris RJ, Chang CF, Chan A, Tankersley MA (2010) Impact of adherence to interferons in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a non-experimental, retrospective, cohort study. Clin Drug Investig 30:89–100

Costello K, Kennedy P, Scanzillo J (2008) Recognizing nonadherence in patients with multiple sclerosis and maintaining treatment adherence in the long term. Medscape J Med 10:225

Baker DP, Pepinsky RB, Brickelmaier M, Gronke RS, Hu X, Olivier K, Lerner M, Miller L, Crossman M, Nestorov I, Subramanyam M, Hitchman S, Glick G, Richman S, Liu S, Zhu Y, Panzara MA, Davar G (2010) PEGylated interferon beta-1a: meeting an unmet medical need in the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. Interferon Cytokine Res 30:777–785

Calabresi PA, Kieseier BC, Arnold DL, Balcer LJ, Boyko A, Pelletier J, Liu S, Zhu Y, Seddighzadeh A, Hung S, Deykin A, ADVANCE Study Investigators (2014) Pegylated interferon β-1a for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (ADVANCE): a randomised, phase 3, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol 13:657–665

Kieseier BC, Arnold DL, Balcer LJ, Boyko AA, Pelletier J, Liu S, Zhu Y, Seddighzadeh A, Hung S, Deykin A, Sheikh SI, Calabresi PA (2015) Peginterferon beta-1a in multiple sclerosis: 2-year results from ADVANCE. Mult Scler 21:1025–1035

Bhargava P, Newsome SD (2016) An update on the evidence base for peginterferon β1a in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 9:483–490

Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL et al (1998) Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess 2:i–iv 1-88

Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H (2000) Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs 32:1008–1015

Devonshire V, Lapierre Y, Macdonell R (2011) The Global Adherence Project (GAP): a multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 8:69–77

Giovannoni G, Southam E, Waubant E (2012) Systematic review of disease-modifying therapies to assess unmet needs in multiple sclerosis: tolerability and adherence. Mult Scler 18:932–946

Halper J, Centonze D, Newsome SD, Huang DR, Robertson C, You X, Sabatella G, Evilevitch V, Leahy L (2016) Management strategies for flu-like symptoms and injection-site reactions associated with peginterferon beta-1a: obtaining recommendations using the Delphi technique. Int J MS Care 18:211–218

Hendin B, Huang D, Wray S, Naismith RT, Rosenblatt S, Zambrano J, Werneburg B (2017) Subcutaneous peginterferon β-1a injection-site reaction experience and mitigation: Delphi analysis of the ALLOW study. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 7:39–47

Naismith RT, Hendin B, Wray S et al (2019) Patients transitioning from non-pegylated to pegylated interferon beta-1a have a low risk of new flu-like symptoms: ALLOW phase 3b trial results. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 5:2055217318822148

Reess J, Haas J, Gabriel K, Fuhlrott A, Fiola M (2002) Both paracetamol and ibuprofen are equally effective in managing flu-like symptoms in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients during interferon beta-1a (AVONEX) therapy. Mult Scler 8:15–18

Rice GP, Oger J, Duquette P (1999) Treatment with interferon beta-1b improves quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci 26:276–282

Río J, Nos C, Bonaventura I (2004) Corticosteroids, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen for IFNbeta-1a flu symptoms in MS: a randomized trial. Neurology 63:525–528

Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W (1996) Therapeutic expectations of patients with multiple sclerosis upon initiating interferon beta-1b: relationship to adherence to treatment. Mult Scler 2:222–226

Kolb-Mäurer A, Sunderkötter C, Kukowski B, Meuth SG, members of an expert meeting (2019) An update on peginterferon beta-1a management in multiple sclerosis: results from an interdisciplinary Board of German and Austrian Neurologists and dermatologists. BMC Neurol 19:130

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the neurologists and nurses who participated in the Delphi study: Lucia Alivernini, Marta Altieri, Annalisa Amidei, Antonella Andreotti, Pietro Osvaldo Luigi Annovazzi, Emilia Basta, Valeria Barcella, Elisabetta Bertini, Annarita Bitetti, Sebastiano Bucello, Martina Campobasso, Marco Capobianco, Patrizia Carta, Elena Cavone, Raffaella Cerqua, Marta Conti, Tommaso Corlianò, Emanuele D'Amico, Elisabetta Di Monte, Sabrina Fabbri, Damiano Faccenda, Paola Gazzola, Clara Guaschino, Shalom Haggiag, Pietro Iaffaldano, Claudia Liguori, Maria Liguori, Giacomo Lus, Simona Malucchi, Giorgia Mataluni, Marina Marchelli, Carmelina Moio, Elena Mutta, Marina Panealbo, Livia Pasquali, Federica Pinardi, Simona Pontecorvo, Pierangela Riani, Daniela Rivola, Marzia Anita Lucia Romeo, Luca Santarelli, Elisabetta Signoriello, Giuseppa Silvestro, Isabella Laura Simone, Rosa Tarantino, Mauro Zaffaroni, and Eleonora Zanella.

Funding

The Consensus Delphi “Pegylated interferon beta 1a (Plegridy) Italian real-world experience: a Delphi analysis of injection-site reaction and flu-like symptom management” was funded by Biogen Italia and managed with the support of Fullcro S.R.L.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception, design, and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants (neurologists and nurses) included in the study.

Code availability

Not applicable

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The original article contains an error. In Table 1, the statement 11bis has been deleted. The correct Table 1 is presented here.The original article contains an error. In Table 1, the statement 11bis has been deleted. The correct Table 1 is presented here.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cordioli, C., Callari, G., Fantozzi, R. et al. Pegylated interferon beta-1a (Plegridy) Italian real-world experience: a Delphi analysis of injection-site reaction and flu-like symptom management. Neurol Sci 42, 1515–1521 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04969-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04969-3