Abstract

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is associated with significant morbidity and economic burden. This study aimed to compare baseline characteristics and patterns of anti-inflammatory drug use and disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) use among patients with RA in Southern Italy versus the United States.

Method

Using Caserta Local Health Unit (Italy) and Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics® Data Mart (United States) claims databases, patients with ≥ 2 diagnosis codes for RA during the study period (Caserta: 2010–2018; Optum: 2010–2019) were identified. Baseline patient characteristics, as well as proportion of RA patients untreated/treated with NSAIDs/glucocorticoids/conventional DMARDs (csDMARDs)/biological/targeted synthetic DMARDs (b/tsDMARDs) during the first year of follow-up, and the proportion of RA patients with ≥ 1 switch/add-on between the first and the second year of follow-up, were calculated. These analyses were then stratified by age group (< 65; ≥ 65).

Results

A total of 9227 RA patients from Caserta and 195,951 from Optum databases were identified (two-thirds were females). During the first year of follow-up, 45.9% RA patients from Optum versus 79.9% from Caserta were exclusively treated with NSAIDs/glucocorticoids; 17.2% versus 11.3% from Optum and Caserta, respectively, were treated with csDMARDs, mostly methotrexate or hydroxychloroquine in both cohorts. Compared to 0.6% of RA patients from Caserta, 3.2% of the Optum cohort received ≥ 1 b/tsDMARD dispensing. Moreover, 61,655 (33.7%) patients from Optum cohort remained untreated compared to 748 (8.3%) patients from the Caserta cohort. The subgroup analyses stratified by age showed that 42,989 (39.8%) of elderly RA patients were untreated compared to 18,666 (24.9%) young adult RA patients in Optum during the first year of follow-up. Moreover, a higher proportion of young adult RA patients was treated with b/tsDMARDs, with and without csDMARDs, compared to elderly RA patients (Optum<65: 6.4%; Optum≥65: 1.0%; P-value < 0.001; Caserta<65: 0.8%; Caserta≥65: 0.1%; P-value < 0.001). Among RA patients untreated during the first year after ID, 41.2% and 48.4% RA patients from Caserta and Optum, respectively, received NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, and cs/b/tsDMARDs within the second year of follow-up. Stratifying the analysis by age groups, 50.6% of untreated young RA patients received study drug dispensing within the second year of follow-up, compared to only 36.7% of elderly RA patients in Optum. Interestingly, more young adult RA patients treated with csDMARDs during the first year after ID received a therapy escalation to b/tsDMARD within the second year after ID in both cohorts, compared to elderly RA patients (Optum<65: 7.8%; Optum≥65: 1.8%; Caserta<65: 3.2%; Caserta≥65: 0.6%).

Conclusions

Most of RA patients, with heterogeneous baseline characteristics in Optum and Caserta cohorts, were treated with anti-inflammatory/csDMARDs rather than bDMARDs/tsDMARDs during the first year post-diagnosis, especially in elderly RA patients, suggesting a need for better understanding and dealing with barriers in the use of these agents for RA patients.

Key Points |

|---|

• Substantial heterogeneity in baseline characteristics and access to bDMARD or tsDMARD drugs between RA patients from the United States and Italy exists. |

• Most of RA patients seem to be treated with anti-inflammatory/csDMARD drugs rather than bDMARD/tsDMARD drugs during the first year post-diagnosis. |

• RA treatment escalation is less frequent in old RA patients than in young adult RA patients. |

• An appropriate use of DMARDs should be considered to achieve RA disease remission or low disease activity. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that affects the joints, connective tissues, muscle, tendons, and fibrous tissue and is associated with significant morbidity and economic burden [1,2,3,4]. The estimated prevalence of RA worldwide varies between 0.3 and 1% and is more common in women and in developed countries [5]. In the United States (US), RA affects approximately 1.3 million adults [6, 7]. In Italy, the RA prevalence is 0.3–0.7%, confirming a higher prevalence in women than in men [8]. RA commonly affects patients aged 30–50 years old [9], and in patients aged above 60, the prevalence is equal to 2% [10].

Elderly RA patients present frequently comorbidity such as cognitive impairment, depression, and frailty [11]. High incidence of comorbidities and drug-related adverse effects in elderly patients also raise therapeutic challenges for the disease management and to achieve a clinical remission of the disease [12, 13].

Evidence from the literature indicates that, despite available treatments, several unmet needs still exist with regard to RA management [14, 15]. Patients with RA experience substantial levels of pain and are not satisfied with their levels of physical functioning even with ongoing treatment [16]. Currently, the main therapeutic target for RA patients is achieving clinical remission, with low disease activity as the best possible alternative [17], to prevent functional impairment and disability [18, 19]. According to national and international guidelines and recommendations [17, 20, 21], several treatments for RA are available: glucocorticoids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs), and biological DMARDs (bDMARDs).

According to the disease severity, the use of these agents aims at controlling systemic inflammation to slow or prevent the disease progression. Methotrexate is considered the standard of care for RA; in patients with at least one contraindication such as severe hepatic or renal impairment, serious, acute, or chronic infections, and other contraindications or intolerance to methotrexate, leflunomide, or sulfasalazine could be considered as options in the first-line strategy of treatment. Moreover, if the treatment target is not achieved with the first csDMARD strategy, addition/switch to a tsDMARD or a bDMARD is recommended [17, 20, 21].

Over the past 20 years, the management of RA has radically changed. The choice of therapies, which were previously mostly based on csDMARDs, has expanded with the marketing of bDMARDs and, more recently, with the new class of tsDMARDs [22]. In particular, the introduction of bDMARDs has revolutionized treatments for RA, with a substantial positive effect on the quality of care of RA patients who suffer from moderate-to-severe disease or who have failed to improve with other medications [23]. However, due to the high cost of these drugs, heterogeneity in access to bDMARDs in RA patients across Europe has been observed [24].

In 2013, the European Medicine Agency (EMA) approved the first infliximab biosimilar, while the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) did in 2016. In general, biosimilars provide a 20–30% purchase cost reduction in comparison to the reference product, representing a valid cost containing strategy [25]; although health resources are limited, it is widely shared that innovative medicines should be made available to all citizens; as new biologic drugs are expensive, correct management strategies must be implemented.

Although the use of biologics has revolutionized the RA therapeutic landscape, leading to major changes in therapeutic targets, concerns about decreased efficacy due to immune senescence and a low benefit-risk profile in the elderly have led to a relative underutilization of biologics [26]. A rapidly ageing population and increasing rates of RA make the paucity of data in older adults with RA an increasingly important clinical issue.

Moreover, since the efficacy and safety of b/tsDMARDs have been thoroughly investigated in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) [27], real-world studies exploring the pattern of use of RA treatments in routine rheumatology practice considering unselected patients potentially representing the entire spectrum of disease severity are needed. The main objective of this study is to evaluate and compare the baseline characteristics and the pattern of real-world use of drugs (e.g., anti-inflammatory drugs and DMARDs) for the treatment of RA in Southern Italy versus the United States. The second aim of this study is to compare the pattern of real-world use of drugs for the treatment of RA young adult versus elderly RA patients in both countries.

Materials and methods

Data sources

This is a retrospective, cross-national cohort study. Data were extracted from Caserta Local Health Unit (LHU)-Italy and Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics® Data Mart-United States claims databases (DBs), covering 1.1 million and 53.3 million individuals, respectively, from January 2010 to September 2019 (Caserta: Jan 2010–Dec 2018). In particular, collected Italian data included demographics, outpatient pharmacy, hospital discharge database, requests for outpatient diagnostic tests and specialist’s visits, exemptions from healthcare service co-payment, and emergency department visit databases. All databases can be linked through an anonymous subject identifier. In addition, general practitioner’s prescriptions (from Arianna database) with related indication for use as well as electronic therapeutic plans (filled by the specialist and including information on drug prescribed, indication for use, drug dosages, and therapy duration) and results of diagnostic tests are collected in Caserta database. The Caserta LHU claims and General Practitioner Arianna databases have been shown to provide accurate and reliable information for pharmacoepidemiological research, as documented elsewhere [28,29,30,31,32]. In Caserta LHU DB, drug dispensing is coded using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system or specific Italian market authorization code (AIC), while indications for use and causes of hospitalizations are coded using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification (ICD9-CM). In Optum DB, drug dispensing is coded using generic names or J/Q codes if applicable, while indications for use and causes of hospitalizations are coded using ICD9-CM or ICD-10 codes.

Moreover, in Italy, biological drugs are fully reimbursed by the National Health Service (NHS) and for each biologic drug prescription, specialists have to fill a therapeutic plan, which indicates the exact drug name, number of dispensed packages, dosing regimen, and indication for use. Electronic therapeutic plans were available in the Caserta LHUs. These data can be linked through unique and anonymous patient identifiers to other claims databases, which contain several types of information, including causes of hospitalization and reasons for healthcare service co-payment exemptions.

Optum Clinformatics® Data Mart (CDM) is derived from a database of de-identified administrative health claims for members of large commercial and Medicare Advantage health plans. The database includes approximately 17–19 million annual covered lives, for a total of over 62 million unique lives over a 13-year period (1/2007 through 12/2020). Clinformatics® Data Mart is statistically de-identified under the Expert Determination method consistent with HIPAA and managed according to Optum® customer data use agreements. CDM administrative claims submitted for payment by providers and pharmacies are verified, adjudicated, and de-identified prior to inclusion. This data, including patient-level enrollment information, is derived from claims submitted for all medical and pharmacy healthcare services with information related to healthcare costs and resource utilization. The population is geographically diverse, spanning all 50 states. Optum de-identified CDM contains longitudinal information on medical and pharmacy claims from a number of different managed care plans, including hospitalizations, outpatient visits, procedures, and pharmacy dispensing. All the medical/pharmacy claims through Optum insurance are recorded in the database as long as the patients were still enrolled in the insurance. As reported for Caserta LHU claims and General Practitioner Arianna databases, Optum Clinformatics® Data Mart has been shown to provide accurate and reliable information for pharmacoepidemiological research, as documented elsewhere [33,34,35,36].

Study population

All patients aged ≥ 18 years with at least two RA diagnoses separated by ≥ 7 days but < 365 days were eligible for the study cohort. The date of the second RA diagnosis was defined as the index date (ID), and patients were required to have at least 1-year pre- and post-index continuous enrollment in their databases to ensure comprehensive availability of data on their healthcare use over this period [36,37,38]. In the Optum database, RA diagnoses were identified based on RA ICD-9 codes (714.xx) or ICD-10 codes (M05.xx, M06.xx, M08.xx, M12.xx) from inpatient or outpatient medical claims. In the Caserta database, RA diagnoses were identified based on RA ICD-9 codes (714.xx) from discharge diagnosis or emergency department visits or electronic therapeutic plans or from the General Practitioner database (i.e., Arianna database) which can be linked through anonymous subject identifier with claims databases. All patients with any csDMARD, bDMARD, or tsDMARD dispensing any time prior to the first RA diagnosis date were excluded. The identification criteria for the study cohort are shown in Online Resource 1.

Exposure assessment

All the following drug classes were included: anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., NSAIDs and glucocorticoids), csDMARDs (e.g., methotrexate, sulfasalazine, leflunomide, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, cyclosporine, azathioprine, auranofin, and sodium aurotiosulfate), bDMARDs, both originators and biosimilars (e.g., etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, anakinra, abatacept, sarilumab, tocilizumab, and rituximab), and tsDMARDs (e.g., tofacitinib and baricitinib). Upadacitinib was not included because it was approved by EMA and by FDA in 2019. Online Resource 2 shows all the included drugs for this study.

Data analysis

In each cohort, the following baseline patient characteristics were assessed: sex, age (categorized as follows: 18–44, 45–64, 65–79, ≥ 80, mean ± standard deviation) at ID, index year, geographic area of patients, comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic pulmonary disease, lipid metabolism disorders, chronic renal failure, liver disease, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, malignancy, smoking, obesity, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel diseases) evaluated within 1 year prior to ID, number of unique prescription drugs based on generic names (categorized as 0, 1, 2, 3–5, 6–10, > 10) evaluated within 1 year prior to ID, and concomitant drugs (e.g., traditional NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, opioids, antidepressant drugs, antihypertensive drugs, insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents, and lipid lowering agents) evaluated within 1 year prior to ID.

The proportion of RA patients treated or untreated within 1 year after ID in each cohort was calculated. Patients were categorized as follows:

-

(a)

Untreated patients: patients without any study drug dispensing;

-

(b)

Exclusive NSAID users: patients with at least one NSAID dispensing AND no dispensing of oral/parenteral glucocorticoids/bDMARD/csDMARD/tsDMARD;

-

(c)

Glucocorticoid (± NSAID) users: patients with at least one oral/parenteral glucocorticoid dispensing AND no dispensing of csDMARD/bDMARD/tsDMARD;

-

(d)

csDMARD (± glucocorticoid ± NSAID) users: patients with at least one csDMARD dispensing AND no dispensing of bDMARD/tsDMARD; or

-

(e)

bDMARD/tsDMARD (± NSAID ± glucocorticoid ± csDMARD) users: patients with at least one bDMARD or tsDMARD dispensing.

Moreover, the proportion of each treatment type among RA patients, after excluding those who were never treated during the follow-up, was calculated. This analysis was then stratified by active substance, distinguishing between originator and biosimilar bDMARDs. Moreover, the proportion of RA patients with at least one switch/add-on between the first and the second year post-ID was calculated. Only RA patients with at least 2 years post-index continuous enrollment in the database were included.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses of the proportion of RA patients untreated or treated within 1 year after ID in each cohort and of the proportion of RA patients with at least one switch/add-on between the first and the second year post-ID were conducted according to age (< 65; ≥ 65).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for the aforementioned baseline variables. For comparisons between the two cohorts, a standardized mean difference (SMD) greater than 0.1 was considered as a sign of imbalance [39]. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

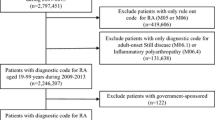

During the study period, 195,951 and 9227 subjects with a diagnosis of RA were identified from Optum and Caserta databases, respectively (Fig. 1). RA prevalence was higher in Caserta (1.1%) than in Optum (0.6%). Of these, more than two-thirds were female patients in both cohorts [Optum: N = 133,605 (68.2%); Caserta: N = 6117 (66.3%); SMD = 0.0408]. RA patients from Optum were older than those from Caserta (mean age ± SD: 66.8 ± 14.2 years in Optum vs. 57.1 ± 16.1 years in Caserta; SMD = 0.6788) (Table 1). In particular, 119,026 (60.7%) and 3203 (34.7%) RA patients were aged 65 years or over, in Optum and Caserta, respectively.

Flow chart of the study cohort. Legend: LHU, Local Health Unit; csDMARDs, conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; bDMARDs, biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; tsDMARDs, targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. *Data available until December 2018. °Data available until September 2019. Patients: (a) age ≥ 18 years; (b) ≥ 2 diagnoses of RA, separated by ≥ 7 days but < 365 days; (c) ≥ 1 year pre-index and 1-year post-index date continuous enrollment in their databases

In general, compared to the Caserta cohort, a higher proportion of the Optum cohort had comorbidities at baseline (80.0% vs. 63.2%). Specifically, hypertension [Optum: N = 131,949 (66.3%); Caserta: N = 4350 (47.1%); SMD = 0.4294] and hyperlipidemia [Optum: N = 115,589 (59.0%); Caserta: N = 1656 (17.9%); SMD = 0.8431] were the two most common comorbidities in both cohorts. In both cohorts, less than 2% of RA patients had other autoimmune disorders for which bDMARDs might be indicated (e.g., inflammatory bowel diseases and psoriasis). Interestingly, 40.2% of patients from both cohorts had received more than 10 drugs during the 1-year period prior to the ID. Half of RA patients from Optum had received at least one dispensing for opioids, compared to 14% of RA patients from Caserta (SMD = 0.7305). Contrarily, 7531 (81.6%) and 2242 (24.3%) in the Caserta cohort had received traditional NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors, respectively, versus 79,690 (40.7%) and 10,318 (5.3%) in the Optum cohort (SMDtraditional NSAIDs = 0.8397; SMDCOX-2 inhibitors = 0.8014).

DMARD treatment patterns

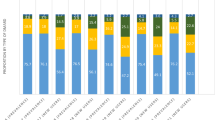

During the first year of follow-up, one-third (N = 61,655; 33.7%) of RA patients from Optum were untreated with NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, or any DMARDs, compared to 748 (8.3%) RA patients from Caserta (P-value < 0.001). Among treated patients, almost half (84,036; 45.9%) of RA patients from Optum versus more than two-thirds (N = 7199; 79.9%) from Caserta received NSAIDs/glucocorticoids dispensing (P-value < 0.001), but they did not receive specific RA treatments (e.g., csDMARDs, bDMARDs, or tsDMARDs); 17.2% of patients from Optum versus 11.3% of patients from Caserta were treated with csDMARDs (P-value < 0.001) (Fig. 2), mostly methotrexate or hydroxychloroquine in both cohorts. No sodium aurothiosulfate users were identified in both cohorts (Online Resource 3). Compared to 3.2% of RA patients from Optum, only 0.6% of RA patients from Caserta had at least one bDMARD/tsDMARD dispensing, with and without csDMARDs (P-value < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The most frequently used bDMARD was the adalimumab originator (Optum: 1.4%; Caserta: 0.2%; P-value < 0.001), followed by the etanercept originator (Optum: 1.1%; Caserta: 0.1%; P-value < 0.001). In both cohorts, no patients used anakinra, adalimumab biosimilars, or e rituximab biosimilars; no users of sarilumab were identified in Caserta (Online Resource 3). We found no tsDMARD users in Caserta versus 226 tsDMARD users (224 tofacitinib and 2 baricitinib) in Optum.

Frequency (%) of treatment lines within the first year after ID. Legend: DMARD, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; tsDMARD, targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; bDMARD, biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug

The subgroup analysis stratified by age showed that 42,989 (39.8%) of elderly RA patients were untreated compared to 18,666 (24.9%) young adult RA patients in Optum (P-value < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Specifically, 14,851 (13.7%) elderly RA patients versus 16,553 (22.1%) young adult RA patients from Optum received csDMARDs during the first year after ID (P-value < 0.001). Concerning the use of csDMARDs from the Caserta cohort, no statistically significant differences were observed in the two age groups compared. Regarding the use of bDMARDs/tsDMARDs, a higher proportion of young adult RA patients was treated with bDMARDs/tsDMARDs, with and without csDMARDs, compared to elderly RA patients (Optum < 65: 6.4%; Optum ≥ 65: 1.0%; P-value < 0.001; Caserta < 65: 0.8%; Caserta ≥ 65: 0.1%; P-value < 0.001).

Frequency (%) of treatment lines within the first year after ID, stratified by age group. Legend: DMARD, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; tsDMARD, targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; bDMARD, biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug

Among untreated RA patients during the first year after ID, 41.2% from Optum and 48.4% from Caserta received at least one study drugs dispensing within the second year of follow-up (P-value < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Proportion (%) of RA patients with at least one switch/add-on between the first and the second year after ID. Legend: DMARD, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; tsDMARD, targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; bDMARD, biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug

In general, almost two-thirds (63.3%) of US elderly RA patients versus 49.4% of young adult RA patients continued to be untreated between the first and the second year after ID (P-value < 0.001).

Stratifying the analysis by age groups, more than half (50.6%) of untreated young RA patients during the first year after ID received study drug dispensing within the second year of follow-up, compared to only 36.7% of elderly RA patients in Optum (P-value < 0.001). Among untreated patients from Caserta, no statistically significant differences were observed in the two compared age groups (P-value: 0.689) (Fig. 5). Interestingly, more young adult RA patients treated with csDMARDs during the first year after ID received a therapy escalation to b/tsDMARD within the second year after ID in both cohorts, compared to elderly RA patients (Optum < 65: 7.8%; Optum ≥ 65: 1.8%; P-value < 0.001; Caserta < 65: 3.2%; Caserta ≥ 65: 0.6%; P-value: 0.012).

Proportion (%) of RA patients with at least one switch/add-on between the first and the second year after ID, stratified by age. Legend: DMARD, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; tsDMARD, targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; bDMARD, biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug

Discussion

This large retrospective cross-national population-based cohort study investigated the baseline characteristics and the pattern of use of different pharmacological treatment lines (anti-inflammatory drugs, csDMARDs, bDMARDs, and tsDMARDs) in patients with RA from the US and Italy over the 10-year study period. Our data about RA prevalence suggest that it was higher in Caserta than in Optum, but in line with prevalence reported in literature [5, 7, 8]. As expected, the distribution by sex showed a female/male ratio equal to 2:1 in both cohorts. In general, a higher proportion of RA patients from Optum had comorbidities at baseline, and they were older than RA patients from Caserta. Specifically, hypertension and hyperlipidemia were the two most common comorbidities, followed by obstructive pulmonary disease, in both cohorts. This is in line with a prospective Swedish study [40] as well as a cohort study using a commercial and Medicare claims database with national beneficiaries [36], showing that 47.1% and 39.3% of RA patients had history of hypertension, followed by 31.9% patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

In both our cohorts, less than 2% of RA patients had history of other autoimmune disorders for which bDMARDs might be indicated (e.g., inflammatory bowel diseases and psoriasis), as reported by Jin et al. [36]. This is also due by the exclusion of all RA patients with at least one csDMARD, bDMARD, or tsDMARD dispensing any time prior to the first RA diagnosis date.

On average, RA patients from both cohorts had received more than 10 drugs within 1 year prior to the ID. Half of RA patients from Optum had received at least one dispensing for opioids, compared to 14% of RA patients from Caserta. It is known that abuse of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain is very common in the US. Recent years have seen an “opioid crisis” take place in the US, with widespread overuse and misuse of opioids, leading to a large number of overdose-related deaths [30, 41]. Zamora-Legoff et al., in a population-based study including RA patients from the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP), a special record-linkage system that records all inpatient and outpatient encounters among the residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, showed that over a third of RA patients used opioids, and in more than a tenth, the use was chronic [42]. Contrarily, our findings showed a higher use of traditional NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors at baseline among RA patients from Caserta than those in the US. The highest use of NSAIDs in Italy was confirmed by an Italian population-based study evaluating the clinical characteristics of elderly analgesic users in Caserta LHU and the frequency of potentially inappropriate analgesic use [30]. The study showed that, among 94,820 elderly persons receiving at least one analgesic drug, 36.6% were incident NSAID users, while 13.2% were incident weak opioid users and 8.1% were incident strong opioid users. Specifically, 9.2% of all elderly analgesic users were considered to have an inappropriate prescription for the NSAIDs (ketorolac or indomethacin) [30].

During the first year of follow-up, one-third of RA patients from Optum seem to be untreated with either NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, or any DMARDs, compared to 8% of RA patients from Caserta. Specifically, almost 40% of US elderly RA patients were untreated compared to 25% of US young adult RA patients during the first year after ID, while no statistically significant differences were observed in the two age groups compared in the Caserta cohort. Moreover, our results showed that, overall, among untreated RA patients, almost half of patients from both study cohorts received at least one study drug dispensing within the second year of follow-up; however, almost two-thirds of US elderly RA patients versus half of young adult RA patients continued to be untreated between the first and the second year after ID. This is in line with a previous study, showing that more than 50% of adults aged 45 years or older with some forms of arthritis remain untreated, despite many of them experiencing severe symptoms and poor physical function [43]. Nevertheless, an exploratory analysis showed that the proportion of untreated RA patients decreased to 6% in Optum and 2% in Caserta within 3 years after ID (data not shown). Regarding those treated, almost half of RA patients from Optum versus more than two-thirds of RA patients from Caserta received NSAIDs/glucocorticoids dispensing, but they did not receive RA-specific DMARD treatments. Among csDMARDs, mostly methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine were used in both cohorts. This is in line with national and international guidelines and recommendations [17, 20, 21]. Methotrexate remains the mainstay 1st-line DMARD in RA; not only is it an efficacious csDMARD by itself but it is also the basis for combination therapies, either with glucocorticoids or with other csDMARDs, bDMARDs, or tsDMARDs. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) guidelines recommend that in patients with a contraindication to methotrexate (or early intolerance), leflunomide or sulfasalazine should be considered as part of the (first) treatment strategy [17, 20]. However, our results showed a low use of leflunomide and sulfasalazine in both countries, compared to hydroxychloroquine. However, EULAR guidelines state that antimalarials, and especially hydroxychloroquine, have a limited role, mainly reserved for patients with mild RA [17] given the only weak clinical and no structural efficacy of hydroxychloroquine [44].

According to the guidelines, bDMARDs/tsDMARDs represent a 2nd line of therapy usually reserved for patients who have failed or have contraindications to csDMARDs [17, 20, 21]. Although RA treatment has made major advances over the past few decades, especially with the introduction of biologics as a treatment option for RA patients, most of the patients in our study were found to be initially treated with anti-inflammatory drugs or csDMARDs rather than bDMARDs. This may be due to the patients in the study having had less severe RA or a state of low disease activity that warranted no treatment with biologic agents. It could also be that patients may still have been kept on csDMARDs despite not achieving remission or low disease activity as recommended in the RA guidelines [17, 20]. Given that claims databases do not collect clinical data on effectiveness or disease activity, we were not able to evaluate these hypotheses.

However, our results are confirmed by an Italian retrospective observational study using claims databases from Veneto, Marche, Abruzzo, Apulia, and Calabria Regions [45]. The mentioned study showed that, as a first treatment, 5% of RA patient received bDMARDs versus 52% were not treated with DMARDs and received no treatment at all or only NSAIDs/glucocorticoids versus 43% of RA patients receiving csDMARDs (83% of csDMARD users continued with the same category of DMARDs during the follow-up).

Similar evidence from the US showed that only 2.6% of RA patients initiated b/tsDMARD treatment within 1 year of diagnosis [46], confirming the low use of bDMARDs/tsDMARDs in our two cohorts, especially in elderly patients from US. A recent retrospective, cohort study using the US Corrona RA registry showed that 54% of RA patients with persistent moderate-to-high disease activity after 6 months of treatment with a csDMARD drug did not receive their therapy escalation. Of the patients who completed a visit at 3–9 months after the index date, treatment advancement occurred in 29% of the patients, with 71% having no change. Dose escalation of the csDMARD, initiation of another csDMARD, and initiation of a bDMARD occurred in 13%, 8%, and 10% of patients of the total population [47].

Our results showed that treatment escalation was less frequent in old RA patients than in young adult RA patients. Different studies have suggested that old RA patients may be less aggressively treated than they should be [10, 26, 48, 49]. The Ruban study reported that despite higher disease activity at diagnosis, elderly-onset RA (EORA) patients were less likely to receive combination DMARD therapies or biologic agents compared with young-onset RA (YORA) patients, even though these drugs (biologics in particular) have been shown to have similar efficacy in older and younger individuals [49]. Howard et al. showed that time to first biologic DMARD is strongly associated with age. The ≥ 75 s were more likely to be on less intensive therapies compared to the < 65 s (csDMARD monotherapy or steroid alone, versus csDMARD combination therapy or bDMARD).

This may in part be due to access, as public payers take longer than private payers to recognize criteria for use and issue approval of advanced therapeutic agents. Indeed, the access to bDMARDs/tsDMARDs still represents an insight. In Italy, although bDMARDs/tsDMARDs are fully reimbursed by the NHS, the access barrier is due to the guidelines, which recommend these high-cost treatments if the treatment target is not achieved with the csDMARD strategy. On the contrary, in the US, the access barrier to these high-cost treatments could be explained by the high median out-of-pocket cost (e.g., $ 40 for bDMARDs and $ 50 for tsDMARDs).

Our study showed that the most frequently used bDMARD was the adalimumab originator, followed by the etanercept originator. A very low proportion of RA patients received infliximab biosimilars, while no users of adalimumab biosimilar and rituximab biosimilar in both cohorts were identified. The first reimbursement approval by the Italian NHS was in July 2017 for rituximab biosimilar and August 2018 for adalimumab biosimilar. Concerning rituximab biosimilar dispensing, it may not be traced in Caserta DB because it was rarely used by Caserta LHU hospitals. Adalimumab biosimilar dispensing may not be traced in the Caserta database because the mean/median times lag between the Italian Drug Agency (AIFA) and Campania Drug Formulary Committee approval could reach some months. In the US, even though five adalimumab and two rituximab biosimilars have been approved by FDA, they were not marketed during the study period [50]. No users of anakinra in both cohorts as well as no users of sarilumab (Italian reimbursement at the end of 2018) in Caserta were identified during the study years. Anakinra was approved for the treatment of moderate‐severe RA but not generally used for RA anymore due to its lower effectiveness when compared to studies using other biologic therapies [51]. Concerning tsDMARDs (i.e., tofacitinib and baricitinib), less than 0.2% of RA users from Optum versus no users in Caserta were identified because of recent reimbursement approval of these drugs.

The main strength of this population-based study is the large size and generalizability of the study cohort and the availability of the claims data from the US as well as a Local Health Unit from Southern Italy for the past decade. We acknowledge some limitations of our study, due to the descriptive nature of the analysis, based on data collected through administrative claims databases. However, real-world observational studies provide evidence on how specific drugs are used in the market and what impact they have in the long-term on the already limited health resources. This is in contrast with randomized controlled trials where data are limited to the experimental conditions of the trial design, and where results may not translate fully to the real-world [52,53,54,55,56]. Second, we cannot exclude a potential misclassification of RA patients from the US, thus resulting in a high proportion of untreated RA patients during the first year of follow-up. However, we defined our cohort selection based on previous studies [36,37,38] and we required all Optum patients to have continuous insurance enrollment during the study period to avoid misclassification due to insurance switching. Furthermore, the traceability of some pharmacy claims, such as NSAIDs/glucocorticoids, might not have been captured by the two databases because they are used as over-the-counter drugs or privately purchased; consequently, the proportion of untreated RA patients could be overestimated; an exploratory analysis was carried using a database provided by IMS Health on pharmacy sales data for all pharmacies in Caserta LHU in the years 2014–2018. Prescription data from IMS are aggregate prescription-level data through which it is possible to distinguish between units of drugs dispensed through the NHS and those purchased privately by citizens. This analysis showed that more than half of NSAIDs and glucocorticoids packages acquired in community pharmacies were bought privately and could not have been captured by the NHS administrative drug dispensing databases. On the contrary, csDMARDs, bDMARDs, and tsDMARDs were fully reimbursed and then traceable. Third, another limitation is represented by the lack of data in the administrative claims databases on clinical outcome measures, such as the effectiveness of treatment, disease severity, and other potential confounders, that could have influenced our results. Finally, our findings from Caserta may not be fully representative of those in the whole Italian general population. However, the applied methodology and the Caserta LHU claims database as well as the Arianna database have been shown to provide accurate and reliable information for pharmacoepidemiological research, as documented elsewhere [28,29,30,31].

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study showed substantial heterogeneity in baseline characteristics and access to bDMARD or tsDMARD drugs between RA patients from the United States and Italy. Most RA patients in our study were treated with anti-inflammatory drugs or csDMARDs, especially elderly, rather than bDMARDs or tsDMARDs during the first year post-diagnosis, suggesting a need for better understanding and dealing with barriers in the use of these agents for diagnosed RA patients. In particular, regardless of age, appropriate use of DMARDs should be considered to achieve RA disease remission or low disease activity. With the increasing spectrum of therapeutic options and the new information on existing drugs, this study could be helpful to provide insights into the management of RA patients in clinical practice.

Data availability

Concerning Caserta Local Health Unit database, fully anonymized dataset is available only upon request to the corresponding author, as there is an agreement between the University of Messina and the data provider (Caserta Local Health Unit) not to share the data publicly.

References

Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK et al (2008) Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum 58(1):15–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.23177

Michaud K, Messer J, Choi HK, Wolfe F (2003) Direct medical costs and their predictors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a three-year study of 7,527 patients. Arthritis Rheum 48(10):2750–62

Yi E, Ahuja A, Rajput T, Thomas AG, Park Y (2020) Clinical, economic, and humanistic burden associated with delayed diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatol Ther 7(1):65–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-020-00194-8

Erol K, Gok K, Cengiz G, Kilic G, Kilic E, Ozgocmen S (2018) Extra-articular manifestations and burden of disease in patients with radiographic and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Acta Reumatol Port 43(1):32–39

World Health Organization (2021) Chronic rheumatic conditions. Available online: https://www.who.int/chp/topics/rheumatic/en/#:~:text=Rheumatic%20or%20musculoskeletal%20conditions%20comprise,and%20conditions%20resulting%20from%20trauma. Accessed on 10 May 2021

Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TMM, Gabriel SE (2010) Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955–2007. Arthritis Rheum 62(6):1576–1582. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.27425

Hunter TM, Boytsov NN, Zhang X, Schroeder K, Michaud KM, Araujo AB (2017) Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the United States adult population in healthcare claims databases, 2004–2014 (2017). Rheumatol Int 37(9):1551–1557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-017-3726-1

Rossini M, Rossi E, Bernardi D, Viapiana O, Gatti D, Idolazzi L et al (2014) Prevalence and incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Italy. Rheumatol Int 34(5):659–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-014-2974-6

Olofsson T, Petersson IF, Eriksson JK et al (2017) Predictors of work disability after start of anti-TNF therapy in a national cohort of Swedish patients with rheumatoid arthritis: does early anti-TNF therapy bring patients back to work? Ann Rheum Dis 76:1245–1252

Tutuncu Z, Kavanaugh A (2007) Rheumatic disease in the elderly: rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 33(1):57–70

Xu X, Li QJ, Xia S, Wang MM, Ji W (2016) Tripterygium glycosides for treating late-onset rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Altern Ther Health Med 22:32–39

Villa-Blanco JI, Calvo-Alen J (2009) Elderly onset rheumatoid arthritis differential diagnosis and choice of first-line and subsequent therapy. Drugs Aging 26:739–750

Leon L, Gomez A, Vadillo C et al (2018) Severe adverse drug reactions to biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis in clinical practice. Clin Exp Rheumatol 36:29–35

Giacomelli R, Afeltra A, Alunno A et al (2017) International consensus: what else can we do to improve diagnosis and therapeutic strategies in patients affected by autoimmune rheumatic diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritides, systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome and Sjogren’s syndrome)?: the unmet needs and the clinical grey zone in autoimmune disease management. Autoimmun Rev 16(9):911–924

Winthrop KL, Strand V, van der Heijde DM (2016) The unmet need in rheumatology: reports from the Targeted Therapies meeting, 2016. Clin Exp Rheumatol 34(4 Suppl 98):69–76

Taylor PC, Moore A, Vasilescu R, Alvir J, Tarallo M (2016) A structured literature review of the burden of illness and unmet needs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a current perspective. Rheumatol Int 36(5):685–695

Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, Burmester GR, Dougados M, Kerschbaumer A et al (2020) EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 79(6):685–699. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216655

Köhler BM, Günther J, Kaudewitz D, Lorenz HM (2019) Current therapeutic options in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Med 8(7):938

Van De Laar CJ, Oude Voshaar MAH, Fakhouri WKH, Zaremba-Pechmann L, De Leonardis F, De La Torre I, Van De Laar MAFJ (2020) Cost-effectiveness of a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor vs a biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (BDMARD) in a treat-to-target strategy for rheumatoid arthritis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 12:213–222

Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, Burmester GR, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M et al (2017) EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 76(6):960–977. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715

Parisi S, Bortoluzzi A, Sebastiani GD, Conti F, Caporali R, Ughi N et al (2019) The Italian Society for Rheumatology clinical practice guidelines for rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatismo 71(S1):22–49. https://doi.org/10.4081/reumatismo.2019.1202

Drosos AA, Pelechas E, Voulgari PV (2020) Treatment strategies are more important than drugs in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 39(4):1363–1368

Scheinberg MA, Kay J (2012) The advent of biosimilar therapies in rheumatology—“O brave new world”. Nat Rev Rheumatol 8(7):430–436. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2012.84

Putrik P, Ramiro S, Kvien TK, Sokka T, Pavlova M, Uhlig T et al (2014) Inequities in access to biologic and synthetic DMARDs across 46 European countries. Ann Rheum Dis 73(1):198–206. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202603

Genazzani AA, Biggio G, Caputi AP, Del Tacca M, Drago F, Fantozzi R et al (2007) Biosimilar drugs: concerns and opportunities. BioDrugs 21(6):351–356. https://doi.org/10.2165/00063030-200721060-00003

Kobak S, Bes C (2018) An autumn tale: geriatric rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 10(1):3–11

Angelini J, Talotta R, Roncato R, Fornasier G, Barbiero G, Dal Cin L, Brancati S, Scaglione F (2020) JAK-inhibitors for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a focus on the present and an outlook on the future. Biomolecules 10(7):1002

Ingrasciotta Y, Sultana J, Giorgianni F, Caputi AP, Arcoraci V, Tari DU et al (2014) The burden of nephrotoxic drug prescriptions in patients with chronic kidney disease: a retrospective population-based study in Southern Italy. PLoS ONE 9(2):e89072. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089072

Ingrasciotta Y, Sultana J, Giorgianni F, Fontana A, Santangelo A, Tari DU et al (2015) Association of individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and chronic kidney disease: a population-based case control study. PLoS ONE 10(4):e0122899. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122899

Ingrasciotta Y, Sultana J, Giorgianni F, Menditto E, Scuteri A, Tari M et al (2019) Analgesic drug use in elderly persons: a population-based study in Southern Italy. PLoS ONE 14(9):e0222836. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222836

Viola E, Trifirò G, Ingrasciotta Y, Sottosanti L, Tari M, Giorgianni F et al (2016) Adverse drug reactions associated with off-label use of ketorolac, with particular focus on elderly patients. An analysis of the Italian pharmacovigilance database and a population based study. Expert Opin Drug Saf 15(sup2):61–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2016.1221401

Oppelt KA, Kuiper JG, Ingrasciotta Y, Ientile V, Herings RMC, Tari M et al (2021) Characteristics and absolute survival of metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with biologics: a real-world data analysis from three European countries. Front Oncol 11:630456. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.630456

Khosrow-Khavar F, Kim SC, Lee H, Lee SB, Desai RJ (2022) Tofacitinib and risk of cardiovascular outcomes: results from the Safety of TofAcitinib in Routine care patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (STAR-RA) study. Ann Rheum Dis 81(6):798–804. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221915

Desai RJ, Pawar A, Khosrow-Khavar F, Weinblatt ME, Kim SC (2021) Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with tofacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 61(1):121–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keab294

Jin Y, Chen SK, Liu J, Kim SC (2020) Risk of incident type 2 diabetes mellitus among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 72(9):1248–1256. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24343

Jin Y, Desai RJ, Liu J, Choi NK, Kim SC (2017) Factors associated with initial or subsequent choice of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 19(1):159. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1366-1

Desai RJ, Solomon DH, Jin Y, Liu J, Kim SC (2017) Temporal trends in use of biologic DMARDs for rheumatoid arthritis in the United States: a cohort study of publicly and privately insured patients. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 23(8):809–814. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.8.809

Kim SY, Servi A, Polinski JM, Mogun H, Weinblatt ME, Katz JN et al (2011) Validation of rheumatoid arthritis diagnoses in health care utilization data. Arthritis Res Ther 13(1):R32. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3260

Austin PC (2009) Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 28(25):3083–3107. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3697

Innala L, Sjöberg C, Möller B, Ljung L, Smedby T, Södergren A et al (2016) Comorbidity in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis—inflammation matters. Arthritis Res Ther 18:33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-0928-y

Skolnick P (2018) The opioid epidemic: crisis and solutions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 58:143–159. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010617-052534

Zamora-Legoff JA, Achenbach SJ, Crowson CS, Krause ML, Davis JM 3rd, Matteson EL (2016) Opioid use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis 2005–2014: a population-based comparative study. Clin Rheumatol 35(5):1137–1144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-016-3239-4

Theis KA, Brady TJ, Sacks JJ (2019) Where have all the patients gone? Profile of US adults who report doctor-diagnosed arthritis but are not being treated. J Clin Rheumatol 25(8):341–347. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000000896

Van der Heijde DM, Van Riel PL, Nuver-Zwart IH, Van de Putte LB (1990) Sulphasalazine versus hydroxychloroquine in rheumatoid arthritis: 3-year follow-up. Lancet 335(8688):539. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(90)90771-v

Perrone V, Losi S, Rogai V, Antonelli S, Fakhouri W, Giovannitti M et al (2021) Treatment patterns and pharmacoutilization in patients affected by rheumatoid arthritis in Italian settings. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(11):5679. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115679

Bonafede M, Johnson BH, Shah N, Harrison DJ, Tang D, Stolshek BS (2018) Disease-modifying antirheumatic drug initiation among patients newly diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Manag Care 24(8 Spec No.):SP279–SP285

Harrold LR, Patel PA, Griffith J, Litman HJ, Feng H, Schlacher CA et al (2020) Assessing disease severity in bio-naïve patients with RA on treatment with csDMARDs: insights from the Corrona Registry. Clin Rheumatol 39(2):391–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04727-7

Kato E, Sawada T, Tahara K et al (2017) The age at onset of rheumatoid arthritis is increasing in Japan: a nationwide database study. Int J Rheum Dis 20(7):839–845

Ruban TN, Jacob B, Pope JE, Keystone EC, Bombardier C, Kuriya B (2016) The influence of age at disease onset on disease activity and disability: results from the Ontario Best Practices Research Initiative. Clin Rheumatol 35(3):759–763

Gherghescu I, Delgado-Charro MB (2020) The biosimilar landscape: an overview of regulatory approvals by the EMA and FDA. Pharmaceutics 13(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13010048

Mertens M, Singh JA (2009) Anakinra for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD005121. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005121.pub3

Saturni S, Bellini F, Braido F, Paggiaro P, Sanduzzi A, Scichilone N et al (2014) Randomized controlled trials and real life studies. Approaches and methodologies: a clinical point of view. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 27(2):129–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pupt.2014.01.005

Garrison LP, Neumann PJ, Erickson P, Marshall D, Mullins CD (2007) Using real-world data for coverage and payment decisions: the ISPOR Real-World Data Task Force Report. Value Health 10:326–335

Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (2011) Demonstrating value with real world data: a practical guide. Available online: http://www.abpi.org.uk/our-work/library/guidelines/Pages/real-world-data.aspx. Accessed on 19 Apr 2017

Nallamothu BK, Hayward RA, Bates ER (2008) Beyond the randomized clinical trial: the role of effectiveness studies in evaluating cardiovascular therapies. Circulation 118:1294–1303

Fakhouri W, Lopez-Romero P, Antonelli S, Losi S, Rogai V, Buda S et al (2018) Treatment patterns, health care resource utilization and costs of rheumatoid arthritis patients in Italy: findings from a retrospective administrative database analysis. Open Access Rheumatol 10:103–111. https://doi.org/10.2147/OARRR.S164738

Funding

This study was in part supported by the internal resources of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The protocol for this study using Optum data received ethics approval from the Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts).

Informed consent

The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Conflict of interest

Ylenia Ingrasciotta is the CEO of the academic spin-off “INSPIRE srl” of the University of Messina, which has received funding for conducting observational studies from contract research organizations (RTI Health Solutions, Pharmo Institute N.V.) and from pharmaceutical Companies (Chiesi Italia, Kyowa Kirin s.r.l., Daiichi Sankyo Italia S.p.A.). Gianluca Trifirò has served on advisory boards/seminars funded by SANOFI, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Abbvie, Servier, Mylan, Gilead, and Amgen; he was the scientific director of a II level Master on pharmacovigilance, pharmacoepidemiology, and real-world evidence, which has received non-conditional contributions from various pharmaceutical companies; he coordinates a pharmacoepidemiology team at the University of Messina, which has received funding for conducting observational studies from various pharmaceutical companies (Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, PTC Pharmaceuticals). He is also chief of the academic spin-off “INSPIRE srl,” which has received funding for conducting observational studies from contract research organizations (RTI Health Solutions, Pharmo Institute N.V.) from pharmaceutical Companies (Chiesi Italia, Kyowa Kirin s.r.l., Daiichi Sankyo Italia S.p.A.). Seoyoung C. Kim has received research grants to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Pfizer, Roche, AbbVie, and Bristol-Myers Squibb for unrelated studies. She is also supported by NIH-K24AR078959. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Seoyoung C. Kim and Gianluca Trifirò share equal contribution as senior author.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10067_2022_6478_MOESM1_ESM.jpg

Online Resource 1. Depiction of the study cohort identification criteria. Legend: Dx: RA diagnosis; MARD: Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug (JPG 193 KB)

10067_2022_6478_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Online Resource 2. Study drugs approved for the treatment of RA. Legend: DMARD: Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug; csDMARD: Conventional Synthetic Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug; tsDMARD: Targeted Synthetic Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug; bDMARD: Biological Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug; AIC= Italian market authorization code; ATC= anatomical therapeutic chemical classification system (PDF 318 KB)

10067_2022_6478_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

Online Resource 3. Frequency (%) of different compound within the first year after ID. Legend: csDMARD: Conventional Synthetic Disease- Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug; tsDMARD: Targeted Synthetic Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug; bDMARD: Biological Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug. Note: Only compounds with proportions ≥0.05% were showed (PDF 188 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ingrasciotta, Y., Jin, Y., Foti, S.S. et al. Real-world patient characteristics and use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-national study. Clin Rheumatol 42, 1047–1059 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06478-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06478-4