Abstract

Infective endocarditis (IE) may be misdiagnosed as ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV), especially when antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are detected. Distinguishing IE from AAV is crucial to guide therapy. However, little is known about ANCA positivity in IE patients. We present a case report and systematic review of the literature on patients with ANCA-positive IE, aiming to provide a comprehensive overview of this entity and to aid clinicians in their decisions when encountering a similar case. A systematic review of papers on original cases of ANCA-positive IE without a previous diagnosis of AAV was conducted on PubMed in accordance with PRISMA-IPD guidelines. A predefined set of clinical, laboratory, and kidney biopsy findings was extracted for each patient and presented as a narrative and quantitative synthesis. A total of 74 reports describing 181 patients with ANCA-positive IE were included (a total of 182 cases including our own case). ANCA positivity was found in 18–43% of patients with IE. Patients usually presented with subacute IE (73%) and had positive cytoplasmic ANCA-staining or anti-proteinase-3 antibodies (79%). Kidney function was impaired in 72%; kidney biopsy findings were suggestive of immune complexes in 59%, while showing pauci-immune glomerulonephritis in 37%. All were treated with antibiotics; 39% of patients also received immunosuppressants. During follow-up, 69% of patients became ANCA-negative and no diagnosis of systemic vasculitis was reported. This study reviewed the largest series of patients with ANCA-positive IE thus far and shows the overlap in clinical manifestations between IE and AAV. We therefore emphasize that clinicians should be alert to the possibility of an underlying infection when treating a patient with suspected AAV, even when reassured by ANCA positivity.

Key Points • This systematic review describes - to our knowledge - the largest series of patients with ANCA-positive infective endocarditis (IE) thus far (N=182), and shows a high degree of overlap in clinical manifestations between IE and ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV). • ANCA positivity was found in 18-43% of patients with infective endocarditis. Of patients with ANCA-positive IE, the majority (79%) showed cytoplasmic ANCA-staining or anti-PR3-antibodies. We emphasize that clinicians should be alert to the possibility of an underlying infection when treating a patient with suspected AAV, even when reassured by ANCA positivity. • In patients with IE and ANCA-associated symptoms such as acute kidney injury, an important clinical challenge is the initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. All patients with data in this series received antibiotics; 39% also received immunosuppressive therapy. In many of these patients, ANCA-associated symptoms resolved or stabilized after infection was treated. ANCA titers became negative in 69% , and a diagnosis of AAV was made in none of the cases. We therefore recommend that (empiric) antibiotic treatment remains the therapeutic cornerstone for ANCA-positive IE patients, while a watchful wait-and-see approach with respect to immunosuppression is advised. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Infective endocarditis (IE) is an uncommon disease with an annual incidence of 3–10 per 100,000 persons. Although relatively rare, it is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, with mortality in the first year estimated at 25–30% [1]. Early diagnosis and treatment are key to improving clinical outcomes. Diagnosis may, however, be difficult as the clinical manifestations of IE are often non-specific, e.g., (low-grade) fever, malaise, and weight loss. Moreover, presenting symptoms are highly variable, including also vascular and immunological phenomena such as petechiae and glomerulonephritis [2]. In the absence of classic IE manifestations, such findings may point the clinician toward an auto-immune instead of an infectious disease, in particular when antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) directed against proteinase-3 (PR3) or myeloperoxidase (MPO) are detected. These antibodies are important diagnostic markers of ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV). Distinguishing IE from AAV is crucial to guide appropriate treatment: While immunosuppressive therapy is the gold standard for vasculitis, this may be detrimental in patients with IE, whose treatment should first aim to eradicate the causative pathogen.

Little is known about the incidence of ANCA positivity in patients with IE, their clinical presentation and renal pathology, the use of immunosuppressive therapy, and their prognosis. In the present review, we first present a case of Streptococcus gallolyticus endocarditis with ANCAs directed against PR3, who presented with arthritis, purpura, and glomerulonephritis and who was treated with antibiotics and, at a later stage, immunosuppressants. We then describe our systematic review of the literature of cases with ANCA-positive IE, focusing on the clinical presentation, renal pathology, treatment, and outcomes, in order to provide a comprehensive overview and more insight into this disease.

Case presentation

A 59-year-old woman presented with a 2-month history of fatigue, weight loss, taste change, dyspnea on exertion, a 2–3-week history of spiking fever, and a 1-day history of a painful, swollen left lower leg. Her medical history included an appendectomy almost 50 years ago and an ovariectomy due to benign adhesions, but it was otherwise unremarkable. She did not use any medication. She quit smoking over twenty years ago and denied intravenous drug use. Her dental health was moderate to poor with tooth loss and occasional transient dental pain.

Significant physical findings included a new grade 3/6 systolic heart murmur heard best over the right second intercostal space, edema of the left foot and ankle with impaired dorsiflexion of the ankle joint, a confluent petechial rash of the anterior left lower leg (Online resource 1), and few petechial hemorrhages of the toes.

Laboratory studies revealed normocytic anemia (hemoglobulin 4.5 mmol/l), mean corpuscular volume of 84 fL without evidence of iron-, folic acid-, or vitamin B12 deficiencies, a white blood cell count of 10.33 × 109/L, C-reactive protein level (CRP) of 54 mg/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of (ESR) 91 mm/hour, a serum creatinine level of 138 μmol/L, and blood urea nitrogen of 5.4 mmol/L. Urinalysis revealed 248 erythrocytes/μL with dysmorphic red blood cells and red blood cell casts on microscopy. The specific antibody assay was positive for anti-PR3 antibodies (14.7 IU/ml, reference <5.0 IU/ml); anti-MPO antibodies and anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies were negative. Rheumatoid factor (IgM) was strongly elevated (>200 IU/ml). Tests for anti-nuclear antibodies and antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens were negative. Serum complement C3 and C4 levels were normal. Serum immunoglobulin (Ig) IgG and IgM levels were increased (28.1 g/L and 2.87 g/L, respectively), with levels of IgG-kappa and IgG-lambda M-proteins too low to be quantitated and normal IgA levels.

Electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia with frequent premature atrial complexes, an incomplete right bundle branch block, and signs of left ventricular hypertrophy. A diseased, bicuspid aortic valve with mild regurgitation and an attached mass, reminiscent of but not typical for endocarditis, as well as evidence of coarctation of the aorta were seen on transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms. Three blood cultures were positive for Streptococcus gallolyticus, subspecies pasteurianus (formerly Streptococcus bovis biotype II). Renal ultrasound ruled out postrenal obstruction, but did show splenomegaly. Ultrasound of the ankle revealed subcutaneous edema, as seen in cellulitis, but no signs of arthritis or synovitis.

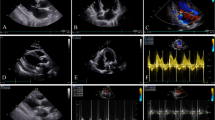

The patient was diagnosed with anti-PR3 antibody-positive infective endocarditis with a not previously diagnosed congenital heart disease, glomerulonephritis, arthritis, and petechiae. She was treated with intravenous benzylpenicillin for a total of 6 weeks. During the first week of antibiotic treatment, her kidney function remained stable. A kidney biopsy was performed, demonstrating crescentic glomerulonephritis (40% cellular, fibrocellular, and fibrous crescents), focal but active lymphocytic tubulointerstitial inflammation, tubular erythrocyte depositions, and mild interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy (Fig. 1A, B). Arteries and arterioles were unremarkable (no endothelialitis/arteriitis). Upon electron microscopy, no subepithelial humps or other glomerular basement membrane abnormalities were observed (Fig. 1C). Immunofluorescence revealed low but notable granular mesangial IgM and C3c staining and kappa- and lambda light chain positivity (all intensity 1+, Fig. 1D–G). IgG, IgA, C1q, and C4d expression was absent. As these findings were not typical of a pauci-immune pattern, both an ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis and an infection-related immune-complex glomerulonephritis were considered.

Representative images of renal biopsy findings. Hematoxylin-eosin staining shows a glomerulus with fibrocellular crescent formation (indicated by the black arrow) at 40× magnification (A). Jones silver staining shows a fibrocellular crescent without abnormalities in the intact portion of the glomerular basement membrane (B, 20× magnification). Electron microscopy showed a few tiny subendothelial depositions (red arrows) without remodeling of the glomerular basement membrane (C). Immunofluorescence revealed granular mesangial and focal subendothelial staining of IgM (D), C3c (E), kappa- (F), and lambda light chain (G; D–G all 20× magnification, all scored as maximum intensity 1+).

Oral prednisone of 60 mg/day was started on the eleventh day of antibiotic treatment (by then, six blood cultures had returned negative). The fever, malaise, and swelling and pain of the ankle joint gradually resolved. The patient was discharged after 15 days with continued antibiotic treatment at home (total duration of 6 weeks). Oral prednisone was gradually tapered off and stopped over the course of approximately four months. Kidney function improved slightly with a serum creatinine level of 100 μmol/L eleven months after presentation. Dental consultation revealed periodontitis; the affected molars were removed. The patient was referred to a cardiologist for further analysis of her congenital heart disease. Considering the association of Streptococcus gallolyticus bacteremia and colorectal tumors, a colonoscopy was performed, revealing a cT1N0M0 carcinoma of the ascending colon [3]. Subsequently, she underwent a laparoscopic right-sided hemicolectomy four months after presentation. Anti-PR3 antibody titers decreased before and after surgery, but remained elevated at 12.3 IU/ml.

Systematic review of literature

Materials and methods

A systematic review of original full-text articles was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-IPD guidelines [4]. All papers reporting on original cases of ANCA-positive, infective endocarditis without a previous diagnosis of AAV were considered, without search restrictions regarding study design, number of cases described, or publication date. The following predefined dataset for each patient was extracted: age, gender, medical history, symptoms at presentation, time from onset symptoms until diagnosis, findings during a physical examination at admission, results of laboratory tests (echocardiograms), renal biopsies (histological and immunofluorescent), treatment, and clinical outcomes. Data are presented as a narrative and quantitative synthesis with descriptive statistics. Further details regarding the search strategy and data collection can be found in Online resource 2.

Results

Literature search and epidemiology

The literature search is depicted in Online resource 3. A total of 74 reports were included in the systematic review, describing 181 patients with ANCA-positive IE (total study set 182 patients including our case). These included 59 case reports [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63], 7 case series [64,65,66,67,68,69,70], 7 retrospective [71,72,73,74,75,76,77], and 1 prospective [78] cohort studies. It is of interest to note that in six of these studies, ANCA testing was performed in cohorts of patients with infective endocarditis, yielding ANCA positivity in 18–43% of cases (median 26%; only the ANCA-positive IE patients of these studies were included in the remainder of the review) [71,72,73,74,75, 78].

Among the 182 cases with ANCA-positive IE, 79% was cytoplasmic ANCA/PR3-positive, compared to 11% perinuclear ANCA/MPO-positive and 8% double-positive. Detailed results of ANCA testing are shown in Online resource 4. Anti-PR3- and/or anti-MPO antibody titers were described in 54 cases: Median increase was 4.5 times the upper reference limit with 50% of titers falling between 2.6 and 8.5 times the upper reference limit, and 40% of cases having titers below 4 times the upper reference limit [6, 7, 9, 10, 13, 16, 24,25,26, 28, 30,31,32,33,34, 36, 38, 39, 41, 42, 46, 47, 49, 51, 52, 54, 56, 60, 65, 66, 68,69,70, 74].

Clinical characteristics and laboratory findings

Clinical characteristics and laboratory findings of the included cases are summarized in Table 1 [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78]. Median age was 55 years, ranging from 6 to 83 years (based on 95 cases). The majority of cases were males (79%) and concerned subacute IE (73%, 56/77 cases; ‘subacute’ defined as such by the authors or when symptoms started ≥1 month prior to presentation). Patients often presented with constitutional symptoms (89%) and a new heart murmur (64%). At presentation, the most common laboratory findings were increased inflammatory markers ESR and/or CRP (97%), anemia (89%), and impaired kidney function (72%). One or more auto-antibodies other than ANCA were frequently found (78%, 71/91 patients tested), with the rheumatoid factor being most commonly identified (63%). Seventeen patients were positive for >1 auto-antibody (33%, 19/57 patients). Circulating immune complexes were described in only four patients, with three yielding positive results (two at admission, one during hospital stay). Cardiac ultrasound revealed vegetations in 79%.

Pathogens

A micro-organism was detected in 131 of 148 cases with data (89%) [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72, 74, 76,77,78]. Details regarding the micro-organisms found are listed in Table 2. Gram-positive bacteria were identified in 88 cases (69%), compared to 42 cases with gram-negative bacteria (33%). In one case, blood cultures were positive for gram-positive as well as gram-negative bacteria. Among the gram-positive bacteria, Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species were identified most frequently, i.e., in 37 (43% of gram-positive) and 30 cases (35%), respectively. Among the gram-negative bacteria, Bartonella species were found in 40 cases (93% of gram-negative).

Renal biopsy findings

In kidney biopsy, the most commonly identified pattern of injury was crescentic glomerulonephritis (51%), followed by proliferative glomerulonephritis (18%) (Table 3) [5,6,7,8, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16, 19,20,21,22, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, 34, 36,37,38,39, 43, 44, 47, 49, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60, 62,63,64, 69, 70, 72, 75,76,77]. Positivity of C1q and/or immunoglobulins, suggestive for immune complexes, was seen in 31% (16/49 cases), while a pauci-immune staining pattern with or without a trace of complement and/or immunoglobulins was reported in 37% (18/49 cases; Online resource 5) [5,6,7, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16, 20, 22, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, 34, 36, 38, 39, 44, 49, 51, 54, 56,57,58, 60, 62, 63, 69, 70, 72, 75,76,77]. Electron microscopy showed electron-dense deposits in 69% (16/23 cases) [5, 12, 13, 15, 16, 20, 22, 26, 28, 30, 31, 44, 52,53,54,55,56,57,58, 60, 62, 69, 77]. Deposits were most commonly identified in subendothelial and mesangial areas (14/16, 88%). Only one case reported a single small subepithelial hump on electron microscopy [57].

Treatment

All cases with treatment details provided (n = 110) received antibiotics [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72, 76, 77]. Of these cases, 43 patients (39%) also received immunosuppressive treatment. This consisted of only corticosteroids (n = 25, 58%), cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids (n = 14, 33%), rituximab and corticosteroids (n = 1, 2%), plasmapheresis and corticosteroids (n = 1, 2%), and immunosuppressant not otherwise specified (n = 2, 5%). In 15% (17/110 cases), immunosuppression was started at a later stage as AAV was suspected. In another 15% (16/110 cases) where immunosuppression was the first treatment and IE was diagnosed later, immunosuppressants were (tapered off and) stopped in 90% (9/10 cases; further details regarding treatments, see Online resource 6). Overall, in patients treated with both antibiotics and immunosuppression, maintenance treatments were given in 14% (n = 6), compared to 65% (n = 23) without (not reported in 9 cases).

Six patients received intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) with reasons for this treatment provided in four cases [7, 13, 58, 66, 69, 76]. In one case, IVIG (2mg/kg) was the initial treatment as the diagnosis was uncertain and kidney biopsy was not possible due to the patient’s clinical condition. When blood cultures returned positive, antibiotics were started [13]. In two patients, corticosteroids and IVIG were started when renal function progressively declined in spite of antibiotics [7, 69]. Finally, one patient who was treated for the suspicion of auto-immune vasculitis with plasmapheresis and corticosteroids was suspected of a complicating infection: Plasmapheresis was stopped, and IVIG started. Immunosuppression was stopped altogether after the diagnosis of IE [58].

Outcomes

Regarding clinical outcomes (Table 4), 84% of patients were alive at the last follow-up, which was a median of 6 months after discharge (range 4 days to 6 years based on 53 cases). Only one patient returned after four months with infective endocarditis with blood cultures positive for the same micro-organism; it is, however, unclear whether this concerned a relapse of disease or re-infection as no typing was described [7]. When kidney function was impaired at presentation, this was restored after treatment in 45% (30/67 cases), and improved but not to pre-existent or normal creatinine levels in 28% (19/67). When looking at treatments given, renal function recovered in 53% receiving only antibiotics (17/32 cases), compared to 43% of cases (12/28) treated with antibiotics and immunosuppressants. These data should be interpreted with caution as immunosuppressants were mostly administered in the patients with persistent deterioration of their renal function. During follow-up, ANCA titers became negative in 69%. The median duration of follow-up was 4 months based on 41 cases. No diagnosis of vasculitis was described during follow-up (data available in 48 cases).

Discussion

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are a hallmark of a subset of small vessel vasculitides, collectively termed ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV). ANCAs, however, are not limited to these vasculitides. Indeed, ANCAs are also detected in various other diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease, and infectious diseases including tuberculosis and endocarditis [79]. We described a case with anti-PR3 antibody-positive infective endocarditis. Multiple case reports and series of this entity have been published; to our knowledge, a comprehensive overview of these cases was lacking. We systematically reviewed the published cases, resulting in the largest series of patients with ANCA-positive IE described thus far (n = 182), aiming to provide an improved understanding of this disease and to aid clinicians in their decisions when encountering a similar case.

Previous studies reported features predominantly seen in IE as compared to AAV, namely, extracardiac manifestations limited to skin and kidneys, splenomegaly, hypocomplementemia, dual ANCA positivity (specifically high PR3/low MPO), increased circulating immune complexes and/or immune complex deposition in histological specimen, other positive auto-antibodies, cryoglobulins, and positive blood cultures [45, 76]. Indeed, skin manifestations (mostly concerning purpura), impaired kidney function, and splenomegaly were frequently found in this much larger series of IE cases (38%, 72%, and 44%, respectively), while in AAV often also pulmonary and central nervous system findings were seen, and splenomegaly is rare. This study also confirms hypocomplementemia as a feature predominantly seen in IE (68% in this study, compared to 11–23% previously described in AAV) [80, 81]. While dual anti-PR3- and anti-MPO-positivity in this series was rare (8%) and therefore does not seem discriminative between IE and AAV, low ANCA titers may aid in this distinction. Forty percent of ANCA-positive IE in our analysis had titers below four times the upper limit of normal, which was previously described as a reasonable cut-off point to discriminate between AAV and other diagnosis with 84% of AAV having titers above this cut-off [82]. Increased circulating immune complexes could not be substantiated as this was described in only three cases; C1q- and/or immunoglobulin positivity, suggestive of immune complexes, were, however, a common finding in renal biopsies (59%). Furthermore, despite the high occurrence of other auto-antibody positivity (78%), this does not seem indicative of ANCA-positive IE. Frequencies identified in this study are similar to or lower than those previously reported for AAV: Rheumatoid factor, anti-phospholipid, and anti-nuclear antibodies were found in 63%, 38%, and 24% of ANCA-positive IE, respectively, compared to 39–60%, 21–26%, and 50% of AAV [83,84,85,86,87]. Finally, sex may be added as a discriminative factor, as 79% of ANCA-positive IE cases concerned males, which is in line with male-to-female ratios in IE regardless of ANCA positivity (i.e., 3:2 to 9:1), but higher compared to the 1:1 ratio noted in AAV [88,89,90].

With pending blood culture results and frequent decline of kidney function, a kidney biopsy was performed in 71 cases, aiming to establish the diagnosis and guide treatment. Similar to the clinical characteristics, much overlap exists in renal pathology findings between glomerulonephritis in (subacute) infective endocarditis and ANCA-mediated glomerulonephritis. One or more features favoring the diagnosis of AAV were commonly identified with crescentic glomerulonephritis reported in 51%, and a negative or pauci-immune immunofluorescence pattern in 37%. Interestingly, in none of the kidney biopsies, an immune infiltrate consisting of predominantly plasma cells is described, while AAV often contains many plasma cells whose role remains to be elucidated. Features favoring the diagnosis of glomerulonephritis associated with IE are the presence of proliferative glomerulonephritis (18%) and of immune complexes and/or complement depositions (63%).

This diagnostic uncertainty was also reflected in the treatment decisions made. While all patients, whose treatment details were provided, received antibiotics at some point in the course of the disease, 39% of patients also received immunosuppressive treatment. This therapy was administered more often to patients with an impaired kidney function at presentation (40% compared to 21% of patients with normal renal function) and, as was the case in our patient, to patients with renal biopsy findings reminiscent of ANCA-mediated glomerulonephritis. From our study, we can deduct that in many of the described cases with ANCA-associated symptoms, such as acute kidney injury, these symptoms resolved or stabilized after the infection was successfully treated. Importantly, no diagnosis or long-lasting features of AAV were reported during reported follow-up of IE patients. Moreover, in 89% of ANCA-positive IE patients, ANCA titers were negative or decreased after a median follow-up of four months. Given the counterproductive effects of immunosuppression in resolving IE, we therefore strongly recommend that (empiric) antibiotic treatment remains the therapeutic cornerstone for ANCA-positive IE patients while a watchful wait-and-see approach with respect to immunosuppression is advised.

The pathogenesis of ANCA in IE, as well as in AAV, is not fully understood. The bacteria causing IE may play a role. Infections induce neutrophil activation and degranulation, and a process called NETosis. In NETosis, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), i.e., net-like structures composed of DNA, nuclear and granular proteins including MPO and PR3, are released by neutrophils to trap and kill pathogens. NETs thus express potential auto-antigens and have been shown in mice to stimulate ANCA production [91, 92]. This is supported by the presence of other auto-antibodies directed against NET components in the published IE patients with anti-nuclear antibodies in 24% and anti-phospholipid antibodies in 38% (others such as anti-dsDNA-, anti-histone antibodies described too infrequently to draw conclusions). Moreover, a mechanism called molecular mimicry has been postulated, where bacterial antigens may induce the production of antibodies that also have an affinity for self-antigens [93]. S. aureus has been implicated as such an exogenous antigen source, as chronic S. aureus nasal colonization has been associated with higher relapse risk in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (a subset of AAV) [94,95,96]. Furthermore, various pathogens including S. aureus include DNA sequences homologous to PR3-antisense DNA, possibly leading to the production of antigens mimicking the complementary peptide (cPR3). In mice, immunization with cPR3 leads to the production of anti-cPR3- as well as anti-PR3-antibodies [97]. Taken together, these mechanisms may explain why 18–43% of patients with IE showed ANCA positivity in our study. Regarding the patient described in the case report, it should be noted that she not only had IE but also had an early stage colon carcinoma. Although malignancy-associated AAV has been very rarely described and pathogenic events causing vasculitis in cancer patients remain poorly understood, a role in or contribution to the clinical manifestations cannot be ruled out [98].

Interestingly, ANCA positivity seemed particularly high in patients with Bartonella endocarditis, namely 60% in one study, compared to 23% in gram-positive IE in the same study [74]. In other studies with cohorts consisting predominantly of gram-positive IE, percentages of ANCA positivity were similar (18% in Mahr et al. with 70% gram-positive IE [78]; 24% in Langlois et al. with 80% gram-positive IE [72]). One preclinical study showed that B. quintana lipopolysaccharide delayed neutrophil apoptosis, leading to increased antigenic exposure and antibody generation [99]. Whether ANCA positivity is indeed more prevalent among Bartonella endocarditis and what the underlying mechanism is, remains to be elucidated.

In this study, all published cases of ANCA-positive IE were reviewed, resulting in – to our knowledge – the largest case series described thus far and the first systematic review. Only case reports, case series, and cohort studies were included in this report yielding a high risk of selection and publication bias. Furthermore, most studies were retrospective in nature with the quality of the studies depending on the availability and accuracy of records; this resulted in many missing data. We should therefore be careful with drawing conclusions. Despite these limitations, considering the relative rarity of both IE and AAV and the absence of higher-quality evidence, this study provides a valuable overview of the characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with ANCA-positive IE. Previous studies showed that immunoassays for PR3- and MPO-ANCAs had a high diagnostic performance to discriminate AAV from disease controls [100]. The control group contains patients with infectious diseases not otherwise specified. As a considerable number of patients with IE are ANCA-positive, we recommend the inclusion specifically of a group of patients with IE in future studies investigating the diagnostic performance of ANCA tests. This study emphasizes that clinicians should be alert to the possibility of an underlying infection when treating a patient with suspected AAV, even when reassured by the presence of ANCA, especially when the clinical condition and/or renal function continue to deteriorate despite (high dose) immunosuppressive therapy.

References

Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD (2016) Infective endocarditis. Lancet 387:882–893. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00067-7

Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ et al (2015) 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the task force for the management of infective endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 36:3075–3128. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319

Pasquereau-Kotula E, Martins M, Aymeric L, Dramsi S (2018) Significance of Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus association with colorectal cancer. Front Microbiol 9(614). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00614

Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M et al (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD statement. JAMA 313:1657–1665. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.3656

Zhang W, Zhang H, Wu D et al (2020) Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive infective endocarditis complicated by acute kidney injury: a case report and literature review. J Int Med Res 48:300060520963990. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060520963990

Chukwurah VO, Takang C, Uche C et al (2020) Lactobacillus acidophilus endocarditis complicated by pauci-immune necrotizing glomerulonephritis. Case Rep Med 2020:1607141. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1607141

Shi XD, Li WY, Shao X et al (2020) Infective endocarditis mimicking ANCA-associated vasculitis: does it require immunosuppressive therapy?: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 99:e21358. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000021358

Nallarajah J, Mujahieth MI (2020) Bacillus cereus subacute native valve infective endocarditis and its multiple complications. Case Rep Cardiol 2020:8826956. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8826956

Zhang Q, Shi B, Zeng H (2020) Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)-positive patient with infective endocarditis and chronic hepatitis B virus: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 14:90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-020-02373-1

Chavin HC, Sierra M, Vicente L et al (2020) Bartonella endocarditis associated with glomerulonephritis and neuroretinitis. Medicina (B Aires) 80:177–180

Elashery AR, Stratidis J, Patel AD (2020) Double-valve heart disease and glomerulonephritis consequent to abiotrophia defectiva endocarditis. Tex Heart Inst J 47:35–37. https://doi.org/10.14503/THIJ-17-6575

Lacombe V, Planchais M, Boud'Hors C et al (2020) Coxiella burnetii endocarditis as a possible cause of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 59:e44–e45. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez648

Bele D, Kojc N, Perse M et al (2020) Diagnostic and treatment challenge of unrecognized subacute bacterial endocarditis associated with ANCA-PR3 positive immunocomplex glomerulonephritis: a case report and literature review. BMC Nephrol 21:40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-1694-2

Yanai K, Kaku Y, Hirai K et al (2019) Proteinase 3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis complicated by infectious endocarditis: a case report. J Med Case Rep 13:356. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2287-1

Aboud H, Bejjanki H, Clapp WL, Koratala A (2019) Pauci-immune proliferative glomerulonephritis and fungal endocarditis: more than a mere coincidence? BMJ Case Rep 12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2018-229059

Vercellone J, Cohen L, Mansuri S et al (2018) Bartonella endocarditis mimicking crescentic glomerulonephritis with PR3-ANCA positivity. Case Rep Nephrol 2018:9607582. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9607582

di Fonzo H, Villegas Gutsch M, Castroagudin A et al (2018) Agranulocytosis induced by vancomycin. Case Report and Literature Review. Am J Case Rep 19:1053–1056. https://doi.org/10.12659/AJCR.909956

Williams JM, Parimi M, Sutherell J (2018) Bartonella endocarditis in a child with tetralogy of Fallot complicated by PR3-ANCA positive serology, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and acute kidney injury. Clin Case Rep 6:1264–1267. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.1589

Penafiel-Sam J, Alarcon-Guevara S, Chang-Cabanillas S et al (2017) Infective endocarditis due to Bartonella bacilliformis associated with systemic vasculitis: a case report. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 50:706–708. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0042-2017

Cervi A, Kelly D, Alexopoulou I, Khalidi N (2017) ANCA-associated pauci-immune glomerulonephritis in a patient with bacterial endocarditis: a challenging clinical dilemma. Clin Nephrol Case Stud 5:32–37. https://doi.org/10.5414/CNCS109076

Hirano K, Tokui T, Inagaki M et al (2017) Aggregatibacter aphrophilus infective endocarditis confirmed by broad-range PCR diagnosis: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 31:150–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.01.041

Raybould JE, Raybould AL, Morales MK et al (2016) Bartonella endocarditis and pauci-immune glomerulonephritis: a case report and review of the literature. Infect Dis Clin Pract (Baltim Md) 24:254–260. https://doi.org/10.1097/IPC.0000000000000384

Kamar FB, Hawkins TL (2016) Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody induction due to infection: a patient with infective endocarditis and chronic hepatitis C. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2016:3585860. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/3585860

Van Haare HS, Wilmes D et al (2015) Necrotizing ANCA-positive glomerulonephritis secondary to culture-negative endocarditis. Case Rep Nephrol 2015:649763. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/649763

Shah SH, Grahame-Clarke C, Ross CN (2014) Touch not the cat bot a glove*: ANCA-positive pauci-immune necrotizing glomerulonephritis secondary to Bartonella henselae. Clin Kidney J 7:179–181. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sft165

Kawamorita Y, Fujigaki Y, Imase A (2014) Successful treatment of infectious endocarditis associated glomerulonephritis mimicking c3 glomerulonephritis in a case with no previous cardiac disease. Case Rep Nephrol 2014:569047. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/569047

Ghosh GC, Sharma B, Katageri B, Bhardwaj M (2014) ANCA positivity in a patient with infective endocarditis-associated glomerulonephritis: a diagnostic dilemma. Yale J Biol Med 87:373–377

Rousseau-Gagnon M, Riopel J, Desjardins A et al (2013) Gemella sanguinis endocarditis with c-ANCA/anti-PR-3-associated immune complex necrotizing glomerulonephritis with a ‘full-house’ pattern on immunofluorescence microscopy. Clin Kidney J 6:300–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sft030

Veerappan I, Prabitha EN, Abraham A et al (2012) Double ANCA-positive vasculitis in a patient with infective endocarditis. Indian J Nephrol 22:469–472. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-4065.106057

Peng H, Chen WF, Wu C et al (2012) Culture-negative subacute bacterial endocarditis masquerades as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis) involving both the kidney and lung. BMC Nephrol 13:174. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-13-174

Konstantinov KN, Harris AA, Hartshorne MF, Tzamaloukas AH (2012) Symptomatic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive disease complicating subacute bacterial endocarditis: to treat or not to treat? Case Rep Nephrol Urol 2:25–32. https://doi.org/10.1159/000339409

Salvado C, Mekinian A, Rouvier P et al (2013) Rapidly progressive crescentic glomerulonephritis and aneurism with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody: Bartonella henselae endocarditis. Presse Med 42:1060–1061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2012.07.031

Fukasawa H, Hayashi M, Kinoshita N et al (2012) Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis associated with PR3-ANCA positive subacute bacterial endocarditis. Intern Med 51:2587–2590. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.51.8081

Reza Ardalan M, Trillini M (2012) Infective endocarditis mimics ANCA associated glomerulonephritis. Caspian J Intern Med 3:496–499

Agard C, Brisseau JM, Grossi O et al (2012) Two cases of atypical Whipple’s disease associated with cytoplasmic ANCA of undefined specificity. Scand J Rheumatol 41:246–248. https://doi.org/10.3109/03009742.2011.648656

Forbes SH, Robert SC, Martin JE, Rajakariar R (2012) Quiz page January 2012 - acute kidney injury with hematuria, a positive ANCA test, and low levels of complement. Am J Kidney Dis 59:A28–A31. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.06.032

Uh M, McCormick IA, Kelsall JT (2011) Positive cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antigen with PR3 specificity glomerulonephritis in a patient with subacute bacterial endocarditis. J Rheumatol 38:1527–1528. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.101322

Hanf W, Serre JE, Salmon JH (2011) Rapidly progressive ANCA positive glomerulonephritis as the presenting feature of infectious endocarditis. Rev Med Interne 32:e116–e118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revmed.2010.12.017

Robert SC, Forbes SH, Soleimanian S, Hadley JS (2011) Complements do not lie. BMJ Case Rep 2011. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.08.2011.4705

Riding AM, D'Cruz DP (2010) A case of mistaken identity: subacute bacterial endocarditis associated with p-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. BMJ Case Rep 2010. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.09.2010.3299

Wilczynska M, Khoo JP, McCann GP (2010) Unusual extracardiac manifestations of isolated native tricuspid valve endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep 2010. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.11.2009.2502

Teoh LS, Hart HH, Soh MC et al (2010) Bartonella henselae aortic valve endocarditis mimicking systemic vasculitis. BMJ Case Rep 2010. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.04.2010.2945

Sugiyama H, Sahara M, Imai Y et al (2009) Infective endocarditis by Bartonella quintana masquerading as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated small vessel vasculitis. Cardiology 114:208–211. https://doi.org/10.1159/000228645

Zeledon JI, McKelvey RL, Servilla KS et al (2008) Glomerulonephritis causing acute renal failure during the course of bacterial infections. Histological varieties, potential pathogenetic pathways and treatment. Int Urol Nephrol 40:461–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-007-9323-6

Chirinos JA, Corrales-Medina VF, Garcia S et al (2007) Endocarditis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol 26:590–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-005-0176-z

Stollberger C, Finsterer J, Zlabinger GJ et al (2003) Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-negative antiproteinase 3 syndrome presenting as vasculitis, endocarditis, polyneuropathy and Dupuytren's contracture. J Heart Valve Dis 12:530–534

de Corla-Souza A, Cunha BA (2003) Streptococcal viridans subacute bacterial endocarditis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA). Heart Lung 32:140–143. https://doi.org/10.1067/mhl.2003.2

Galaria NA, Lopressti NP, Magro CM (2002) Henoch-Schonlein purpura secondary to subacute bacterial endocarditis. Cutis 69:269–273

Haseyama T, Imai H, Komatsuda A et al (1998) Proteinase-3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) positive crescentic glomerulonephritis in a patient with Down’s syndrome and infectious endocarditis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13:2142–2246. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/13.8.2142

Holmes AH, Greenough TC, Balady GJ et al (1995) Bartonella henselae endocarditis in an immunocompetent adult. Clin Infect Dis 21:1004–1007. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/21.4.1004

Wagner J, Andrassy K, Ritz E (1991) Is vasculitis in subacute bacterial endocarditis associated with ANCA? Lancet 337:799–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(91)91427-v

Paudyal S, Kleven DT, Oliver AM (2016) Bartonella Henselae endocarditis mimicking ANCA associated vasculitis. Case Rep Internal Med 3:3. https://doi.org/10.5430/crim.v3n2p29

Vikram HR, Bacani AK, DeValeria PA et al (2007) Bivalvular Bartonella henselae prosthetic valve endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol 45:4081–4084. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01095-07

Khalighi MA, Nguyen S, Wiedeman JA, Palma Diaz MF (2014) Bartonella endocarditis-associated glomerulonephritis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Kidney Dis 63:1060–1065. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.10.058

Turner JW, Pien BC, Ardoin SA et al (2005) A man with chest pain and glomerulonephritis. Lancet 365:2062. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66701-3

Osafune K, Takeoka H, Kanamori H et al (2000) Crescentic glomerulonephritis associated with infective endocarditis: renal recovery after immediate surgical intervention. Clin Exp Nephrol 4:6

Alawieh R, Satoskar A, Obole E et al (2020) Infection-related glomerulonephritis mimicking lupus nephritis. Clin Nephrol 94:212–214. https://doi.org/10.5414/CN110202

Mohandes S, Satoskar A, Hebert L, Ayoub I (2018) Bacterial endocarditis manifesting as autoimmune pulmonary renal syndrome: ANCA-associated lung hemorrhage and pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis. Clin Nephrol 90:431–433. https://doi.org/10.5414/CN109495

Bauer A, Jabs WJ, Sufke S et al (2004) Vasculitic purpura with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive acute renal failure in a patient with Streptococcus bovis case and Neisseria subflava bacteremia and subacute endocarditis. Clin Nephrol 62:144–148. https://doi.org/10.5414/cnp62144

Dukkipati R, Lawson B, Nast CC, Shah A (2021) Bartonella-associated endocarditis with severe active crescentic glomerulonephritis and acute renal failure. Case Rep Nephrol 2021:9951264. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9951264

Spindel J, Parikh I, Terry M, Cavallazzi R (2021) Leucocytoclastic vasculitis due to acute bacterial endocarditis resolves with antibiotics. BMJ Case Rep 14. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2020-239961

Yoshifuji A, Hibino Y, Komatsu M et al (2021) Glomerulonephritis caused by Bartonella spp. infective endocarditis: the difficulty and importance of differentiation from anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-related rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Intern Med 60:1899–1906. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.5608-20

Messiaen T, Lefebvre C, Zech F et al (1997) ANCA-positive rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis: there may be more to the diagnosis than you think! Nephrol Dial Transplant 12:839–841. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/12.4.839

Ouellette CP, Joshi S, Texter K, Jaggi P (2017) Multiorgan involvement confounding the diagnosis of Bartonella henselae infective endocarditis in children with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J 36:516–520. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000001510

Hirai K, Miura N, Yoshino M et al (2016) Two cases of proteinase 3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA)-related nephritis in infectious endocarditis. Intern Med 55:3485–3489. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.55.7331

Satake K, Ohsawa I, Kobayashi N et al (2011) Three cases of PR3-ANCA positive subacute endocarditis caused by attenuated bacteria (Propionibacterium, Gemella, and Bartonella) complicated with kidney injury. Mod Rheumatol 21:536–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10165-011-0434-7

Tiliakos AM, Tiliakos NA (2008) Dual ANCA positivity in subacute bacterial endocarditis. J Clin Rheumatol 14:38–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0b013e318164187a

Choi HK, Lamprecht P, Niles JL et al (2000) Subacute bacterial endocarditis with positive cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and anti-proteinase 3 antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 43:226–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<226::AID-ANR27>3.0.CO;2-Q

McAdoo SP, Densem C, Salama A, Pusey CD (2011) Bacterial endocarditis associated with proteinase 3 anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody. NDT Plus 4:208–210. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndtplus/sfr030

Subra JF, Michelet C, Laporte J et al (1998) The presence of cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (C-ANCA) in the course of subacute bacterial endocarditis with glomerular involvement, coincidence or association? Clin Nephrol 49:15–18

Ying CM, Yao DT, Ding HH, Yang CD (2014) Infective endocarditis with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody: report of 13 cases and literature review. PLoS One 9:e89777. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089777

Langlois V, Lesourd A, Girszyn N et al (2016) Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies associated with infective endocarditis. Medicine (Baltimore) 95:e2564. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002564

Zhou Z, Ye J, Teng J et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of infective endocarditis in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody or antiphospholipid antibody: a retrospective study in Shanghai. BMJ Open 10:e031512. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031512

Aslangul E (2015) Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity in gram-positive and Bartonella-induced infective endocarditis: comment on the article by Mahr et al. Arthritis Rheumsatol 67:1407–1408. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39046

Boils CL, Nasr SH, Walker PD et al (2015) Update on endocarditis-associated glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 87:1241–1249. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2014.424

Bonaci-Nikolic B, Andrejevic S, Pavlovic M et al (2010) Prolonged infections associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies specific to proteinase 3 and myeloperoxidase: diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Clin Rheumatol 29:893–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-010-1424-4

Satoskar AA, Suleiman S, Ayoub I et al (2017) Staphylococcus infection-associated GN - spectrum of IgA staining and prevalence of ANCA in a single-center cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12:39–49. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.05070516

Mahr A, Batteux F, Tubiana S et al (2014) Brief report: prevalence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in infective endocarditis. Arthritis Rheumatol 66:1672–1677. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.38389

Falk RJ, Merkel PA (2022) Clinical spectrum of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies. UpToDate, Topic 3060 Version 32.0, accessed 22-04-2022

Garcia L, Pena CE, Maldonado RA et al (2019) Increased renal damage in hypocomplementemic patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis: retrospective cohort study. Clin Rheumatol 38:2819–2824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04636-9

Chalkia A, Thomas K, Giannou P et al (2020) Hypocomplementemia is associated with more severe renal disease and worse renal outcomes in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis: a retrospective cohort study. Ren Fail 42:845–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886022X.2020.1803086

Houben E, Bax WA, van Dam B et al (2016) Diagnosing ANCA-associated vasculitis in ANCA positive patients: a retrospective analysis on the role of clinical symptoms and the ANCA titre. Medicine (Baltimore) 95:e5096. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000005096

Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY et al (1992) Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med 116:488–498. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-116-6-488

Moon JS, Lee DD, Park YB, Lee SW (2018) Rheumatoid factor false positivity in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis not having medical conditions producing rheumatoid factor. Clin Rheumatol 37:2771–2779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3902-4

Jordan N, D'Cruz DP (2016) Association of lupus anticoagulant with long-term damage accrual in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Care Res 68:711–715. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22723

Yoo J, Ahn SS, Jung SM et al (2019) Persistent antiphospholipid antibodies are associated with thrombotic events in ANCA-associated vasculitis: a retrospective monocentric study. Nefrologia 39:395–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nefro.2018.10.014

Zhao X, Wen Q, Qiu Y, Huang F (2021) Clinical and pathological characteristics of ANA/anti-dsDNA positive patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated vasculitis. Rheumatol Int 41:455–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04704-3

Hill EE, Herijgers P, Claus P et al (2007) Infective endocarditis: changing epidemiology and predictors of 6-month mortality: a prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J 28:196–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehl427

Lerner PI, Weinstein L (1966) Infective endocarditis in the antibiotic era. N Engl J Med 274:199–206 contd. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM196601272740407

Kitching AR, Anders HJ, Basu N et al (2020) ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 6:71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0204-y

Kraaij T, Kamerling SWA, van Dam LS et al (2018) Excessive neutrophil extracellular trap formation in ANCA-associated vasculitis is independent of ANCA. Kidney Int 94:139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2018.01.013

Sangaletti S, Tripodo C, Chiodoni C et al (2012) Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate transfer of cytoplasmic neutrophil antigens to myeloid dendritic cells toward ANCA induction and associated autoimmunity. Blood 120:3007–3018. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-03-416156

Ramponi G, Folci M, De Santis M et al (2021) The biology, pathogenetic role, clinical implications, and open issues of serum anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Autoimmun Rev 20:102759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102759

Stegeman CA, Tervaert JW, Sluiter WJ et al (1994) Association of chronic nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and higher relapse rates in Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med 120:12–17. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-120-1-199401010-00003

Laudien M, Gadola SD, Podschun R et al (2010) Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and endonasal activity in Wegener s granulomatosis as compared to rheumatoid arthritis and chronic Rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Clin Exp Rheumatol 28:51–55

Salmela A, Rasmussen N, Tervaert JWC et al (2017) Chronic nasal Staphylococcus aureus carriage identifies a subset of newly diagnosed granulomatosis with polyangiitis patients with high relapse rate. Rheumatology (Oxford) 56:965–972. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex001

Pendergraft WF, Preston GA, Shah RR et al (2004) Autoimmunity is triggered by cPR-3(105-201), a protein complementary to human autoantigen proteinase-3. Nat Med 10:72–79. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm968

Mahr A, Heijl C, Le Guenno G, Faurschou M (2013) ANCA-associated vasculitis and malignancy: current evidence for cause and consequence relationships. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 27:45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2012.12.003

Matera G, Liberto MC, Quirino A et al (2003) Bartonella quintana lipopolysaccharide effects on leukocytes, CXC chemokines and apoptosis: a study on the human whole blood and a rat model. Int Immunopharmacol 3:853–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1567-5769(03)00059-6

Damoiseaux J, Csernok E, Rasmussen N et al (2017) Detection of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs): a multicentre European Vasculitis Study Group (EUVAS) evaluation of the value of indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) versus antigen-specific immunoassays. Ann Rheum Dis 76:647–653. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209507

Facklam R (2002) What happened to the streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin Microbiol Rev 15:613–630. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.15.4.613-630.2002

Acknowledgements

We thank J.W.M. Plevier of the Walaeus Library (LUMC) for developing the search strategy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception. The literature search and data analysis were performed by I.C. Van Gool and M.P. Bauer. The manuscript was drafted by I.C. Van Gool. All authors critically reviewed and edited previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent to participate

The patient described in the case report gave her consent for the publication of clinical information and images related to the case.

Disclosures

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Gool, I.C., Kers, J., Bakker, J.A. et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in infective endocarditis: a case report and systematic review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol 41, 2949–2960 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06240-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06240-w