Abstract

Introduction/objectives

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is a common inflammatory disorder that is usually managed with oral glucocorticoids, which although effective can cause significant adverse events. Support group survey data suggests length of glucocorticoid treatment and managing side effects are key priority areas of management for patients. Recognising that not all patients will access patient support organisations, our objective was to identify priorities for PMR management and research among primary care PMR patients.

Method

All adults aged ≥ 50 years registered with 150 English general practices who had a first read code for PMR in their medical records in the preceding 3 years were mailed a self-completion questionnaire (n = 704). Survey items included questions regarding patient priorities for PMR management (from a pre-defined list of 10 items) and suggestions for future research (8 items, plus a free-text option), which were developed in collaboration with PMRGCAuk.

Results

Five hundred fifty patients responded (78%). The mean (SD) age was 74.1 (8.5) years and 361 (66%) were female. Priority research areas were focused on how to better manage pain, stiffness and fatigue (431, 78%), improving the diagnosis of PMR (393, 71%) and steroid management (342, 62%).

Conclusions

This survey of PMR patients suggests that symptom management, early diagnosis and managing medication are key areas for patients for future research. Researchers and funding organisations should be aware of these priorities if we are to generate research findings that are relevant to the widest range of stakeholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is an inflammatory disorder of older adults with a lifetime prevalence of 2.4% in women and 1.7% in men [1]. It classically causes pain and stiffness in the shoulders and hip girdles, which can lead to significant levels of physical disability [2]. The mainstay of treatment is oral glucocorticoids, which whilst effective are often required for prolonged periods [3]. This places patients at potential risk of adverse events and is a key concern for both patients [4] and clinicians [5].

There is increasing evidence that there is a mismatch between what research patients want to see undertaken and research being performed [6]. To address this disparity, the James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnerships were created, where partnerships of patients, carers and health professionals discussed and agreed on important priorities for treatment and research in a range of health conditions, such as type 1 diabetes and stroke. An evaluation of these partnerships [6] suggested that drug trials were preferred by researchers, and non-drug treatments are preferred by patients, carers and clinicians.

Involving patients in research is both best practice [7] and increasingly becoming key to securing research funding with many major funding bodies. However, reviews suggest that although patients should play an active role in setting research priorities, such participation remains the exception rather than the rule [8]. The charity PMRGCAuk was established in 2010 as an online community of patients with PMR or giant cell arteritis. The charity had previously surveyed its membership [9] to identify key priorities for PMR patients for information and support together with areas they wished to see prioritised for future research. Responses suggested that managing glucocorticoids was the key priority for the majority of respondents [9].

Patients who choose to join or access patient support groups or charities may be different to the wider population with a specific condition, with data from cancer survivors suggesting that those accessing support groups were likely to be female [10,11,12], younger [11, 13] and of Caucasian ethnicity [10, 12]. To investigate the broadest range of patient experience, we sought to survey a primary care population of people with PMR, using similar questions to those identified as important in the survey by PMRGCAuk [9]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine patient priorities for living with PMR and their priorities for PMR research within a primary care population.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

A cross-sectional questionnaire study was developed to investigate the impact of PMR. Adults (age ≥ 50 years) with a first read-coded diagnosis of PMR between January 1, 2010 and January 1, 2013 were identified via an electronic search of primary care records from 150 participating general practices across England. The research lead from each practice screened the list of identified patients and removed those in potentially vulnerable groups (e.g. those with significant cognitive impairment or a terminal diagnosis). Those eligible to participate (n = 704) were mailed a study pack, including a questionnaire and consent to participate; non-responders were sent a reminder postcard at 2 weeks and a repeat study pack at 4 weeks. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from NRES-West Midlands-Staffordshire (Ref 13/WM/0133).

Primary care records were used to establish disease duration, taken as time from date of diagnosis to date of questionnaire response. Other results in this article are derived from the questionnaire data. This questionnaire included items relating to sociodemographics (age, gender and personal circumstances), PMR characteristics (e.g. whether currently experiencing symptoms) and health information-seeking behaviour (e.g. whether a doctor had provided written information on PMR). Following collaborative work with the charity PMRGCAuk, we used two questionnaire items related to priorities around PMR which the charity had identified from surveys of users of their telephone helpline [9]. The first item presented ten aspects of living with PMR (e.g. managing pain, see Table 2); participants were asked to select five as priorities. Specifically, the question was “What in your opinion are the most important aspects of living with PMR that people need help with? This help might be information or support?” The second item presented nine areas for further PMR research (e.g. diagnosis, see Table 3): participants were asked to select any number of these as priorities.

Data analysis

Responders and non-responders to the questionnaire were compared in terms of age and gender using a t test (equal variances assumed) and a chi-squared test respectively, to check for evidence of response bias. Other statistics calculated were descriptive: the count and percentage of participants that had selected each aspect of living with PMR or research area as a priority were recorded.

The second questionnaire item regarding research priorities included a free-text ‘other’ option. Responses to the ‘other’ option were categorised using content analysis. Content analysis is a systematic method for interpreting meaning in textual data [14]. First, a single author (CM) read the free-text responses repeatedly in order to gain familiarity with them as a whole. The words capturing the key concept in each response were highlighted. During this process, codes emerged that reflected the key concept in multiple responses. For example, “Why PMR develops and ways to prevent it” and “Causal factors - I blame mine on gall bladder removal” were both coded as “Causes of PMR”. The process was iterative; at each stage, responses could be recoded and codes could be relabelled, created or removed, until all responses were coded to the author’s satisfaction.

A second author (SM) independently coded a random sample of 20 responses using the codes identified by CM. The two authors then compared and discussed their choices. Although there was disagreement on the coding of only one response, the purpose of this exercise was not calculating a statistical rate of agreement. Instead, the emphasis was on bringing the authors’ different perspectives to bear on data interpretation. Disagreement or uncertainty regarding the coding of individual responses was resolved by consensus to establish final categories (Table 4). Responses that were illegible were coded as “do not know” or which had no clear connection to research priorities were removed at this stage.

Results

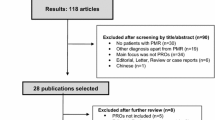

Of the 704 patients that were mailed a questionnaire, 550 (78%) consented to participate (Fig. 1). Non-responders and refusals were older than participants (mean (SD) 75.2 (9.2) years versus 74.1 (SD 8.5), p = 0.17) and more often female (n = 112 (73%) versus n = 361 (66%), p = 0.14), although these differences were not statistically significant. Consistent with other PMR studies, the majority of the sample was female (n = 361, 66%), with a mean age of 74.1 (SD 8.5) years (Table 1). Median (IQR) time since diagnosis was 2.0 (1.3, 2.6) years. Sixty-eight percent (n = 374) of participants were still experiencing PMR symptoms at the date of response. Access to PMR-related information was mixed; 50% of participants (n = 273) reported receiving written information whilst 43% (n = 234) had used the Internet to research PMR. Only 10 participants (2%) had contacted a patient support group.

Priorities for living with PMR

Priorities selected as among the five most important aspects of living with PMR can be seen in Table 2. Ninety-seven percent of participants (n = 533) indicated at least one priority for living with PMR, with the majority selecting five priorities (although 22 selected more than 5 priorities, 58 selected fewer). Managing stiffness (n = 415, 75%) and managing pain (n = 406, 74%) were most commonly identified as areas that required support. Ninety percent of participants (n = 497) selected at least one of these two options. Other frequently selected priorities were management of steroids and other medications (n = 400, 73%), outlook for recovery (n = 376, 68%) and things participants could do to help themselves (n = 355, 65%). Priorities did not differ by disease duration, using a cutoff of greater or less than 2 years, including stiffness (75% vs 76%), pain (73% vs 76%), steroid management (73% vs 77%), outlook for recovery (72% vs 72%) and things patients could do to help themselves (65% vs 63%).

Priorities for PMR research

Areas selected as priorities for PMR research, of which any number could be selected, are displayed in Table 3. Ninety-seven percent of participants (n = 535) indicated at least one research priority, with a median of 4 priorities (interquartile range 3–5) being selected. Pain, stiffness and fatigue were the research area most commonly prioritised (n = 431, 78%), followed by diagnosis (n = 393, 71%), steroid management (n = 342, 62%) and things patients could do themselves for their condition (n = 335, 60%). The risk of developing giant cell arteritis, a key concern for clinicians, was not frequently prioritised by patients and was selected by only 138 (25%). Eight percent of participants (n = 42) used the ‘other’ option to describe research priorities beyond those pre-specified. Eight of these responses were inadmissible: one was illegible, two were “do not know” and five had no clear connection to research priorities. Using content analysis, 10 codes were identified (Table 4) from 35 priorities (one participant indicated two distinct priorities). Treatment side effects (n = 7), causes of PMR (n = 6) and delay in diagnosis (n = 6) were the most frequently cited free-text priorities.

Discussion

PMR is commonly managed in primary care and can have significant long-term impacts for patients. Understanding patient priorities around living with PMR and research priorities is important to ensure research findings generated are relevant to all stakeholders.

This is the first survey of primary care PMR patients to investigate perspectives on the challenges of living with PMR and their priorities for future research. These results highlight that patients are concerned especially with managing symptoms such as pain and stiffness and management of steroids and that these are the areas that patients would prioritise for future research. These findings are similar to previous work surveying PMRGCAuk support group members [4] which highlighted that concerns about steroids are an important issue for patients. Developing giant cell arteritis, a key concern for clinicians [15], was rarely considered as one of the important aspects of living with PMR or as a research priority. It is not clear to what extent this indicates a mismatch between patient and clinical priorities, rather than a lack of patient information regarding giant cell arteritis and its effects.

There are several strengths and weaknesses that need to be considered when interpreting the results of this study. This was a large cohort of PMR patients (550 patients) recruited from across England and as such, the results are likely to be highly generalisable. A limitation is that these patients were included on the basis of a primary care diagnostic code for PMR, rather than having been assessed in specialist services, although the demographics of this population are similar to those seen in both primary [16, 17] and secondary [18] care PMR cohorts. By including patients with a range of disease durations (median 2 years), we may also have captured a different patient experience than those with recent onset disease, although our results suggest that symptom management and medication remains important issues for patients with a longer duration of disease.

In summary, a large primary care survey of people with PMR suggests that management of symptoms such as pain, stiffness and fatigue, diagnosis and managing steroids are key research priorities for patients. Researchers and funding organisations should be aware of these priorities if we are to generate research findings that are relevant to the widest range of stakeholders.

References

Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Myasoedova E, Michet CJ, Ernste FC, Warrington KJ, Davis JM 3rd, Hunder GG, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE (2011) The lifetime risk of adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum 63:633–639. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30155

González-Gay MA, Matteson EL, Castañeda S (2017) Polymyalgia rheumatica. Lancet 390:1700–1712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31825-1

Dasgupta B, Borg FA, Hassan N, Barraclough K, Bourke B, Fulcher J, Hollywood J, Hutchings A, Kyle V, Nott J, Power M, Samanta A, on behalf of the BSR and BHPR Standards, Guidelines and Audit Working Group (2010) BSR and BHPR guidelines for the management of polymyalgia rheumatica. Rheumatol 49:186–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kep303a

Muller S, O’Brien A, Helliwell T, Hay CA, Gilbert K, Mallen CD, Busby K, on behalf of PMRGCAuk (2018) Support available for and perceived priorities of people with polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis: results of the PMRGCAuk members’ survey 2017. Clin Rheumatol 37:3411–3418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4220-1

Helliwell T (2016) Polymyalgia rheumatica in primary care: an exploration of the challenges of diagnosis and management using survey and qualitative methods. PhD Dissertation, Keele University

Crowe S, Fenton M, Hall M, Cowan K, Chalmers I (2015) Patients’, clinicians’ and the research communities’ priorities for treatment research: there is an important mismatch. Res Involv Engagem 1:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-015-0003-x

National Institute for Health Research INVOLVE http://www.invo.org.uk/resource-centre/. Accessed Sept 2018

Sacristán JA, Aguarón A, Avendaño-Solá C, Garrido P, Carrión J, Gutiérrez A, Kroes R, Flores A (2016) Patient involvement in clinical research: why, when, and how. Patient Prefer Adherence 10:631–640. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S104259

Gilbert K (2014) 7. PollyWotsit and the giant dragon: the patient’s perspective on PMR and GCA. Rheumatol 53:i4–i5. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keu189

Stevinson C, Lydon A, Amir Z (2011) Cancer support group participation in the United Kingdom: a national survey. Support Care Cancer 19:675–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0887-9

Grande GE, Myers LB, Sutton SR (2006) How do patients who participate in cancer support groups differ from those who do not? Psychooncology 15:321–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.956

Owen JE, Goldstein MS, Lee JH, Breen N, Rowland JH (2007) Use of health-related and cancer-specific support groups among adult cancer survivors. Cancer 109:2580–2589. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22719

Boyes A, Turon H, Hall A, Watson R, Proietto A, Sanson-Fisher R (2018) Preferences for models of peer support in the digital era: a cross-sectional survey of people with cancer. Psychooncology 27:2148–2154. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4781

Hsieh FH, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15:1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Helliwell T, Muller S, Hider SL, Prior JA, Richardson JC, Mallen CD (2018) Challenges of diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis in general practice: a multimethods study. BMJ Open 8:e019320. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019320

Barraclough K, Liddell WG, du Toit J, Foy C, Dasgupta B, Thomas M, Hamilton W (2008) Polymyalgia rheumatica in primary care: a cohort study of the diagnostic criteria and outcome. Fam Pract 25:328–333. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmn044

Muller S, Hider SL, Helliwell T, Lawton S, Barraclough K, Dasgupta B, Zwierska I, Mallen CD (2016) Characterising those with incident polymyalgia rheumatica in primary care: results from the PMR cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 18:200. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1097-8

Hutchings A, Hollywood J, Lamping DL, Pease CT, Chakravarty K, Silverman B, Choy EH, Scott DG, Hazleman BL, Bourke B, Gendi N, Dasgupta B (2007) Clinical outcomes, quality of life, and diagnostic uncertainty in the first year of polymyalgia rheumatica. Arthritis Care Res 57:803–809. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22777

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff at Keele University’s Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre and the staff and patients of the participating practices and NIHR Clinical Research Networks.

Funding

This study represents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre of Excellence at Keele University. CM is funded by a NIHR School for Primary Care Research studentship. CDM is funded by the National Institute for Health Research Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West Midlands, the NIHR School for Primary Care Research and a NIHR Research Professorship in General Practice (NIHR-RP-2014-04-026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from NRES-West Midlands-Staffordshire (Ref 13/WM/0133) and the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants gave their informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Disclosures

None.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Morton, C., Muller, S., Bucknall, M. et al. Examining management and research priorities in patients with polymyalgia rheumatica: a primary care questionnaire survey. Clin Rheumatol 38, 1767–1772 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-04405-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-04405-0