Abstract

Purpose

The processing of the round ligament of uterus in laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) repair of inguinal hernia in women has contended. This study aimed to explore whether there is any difference in the surgical outcome and postoperative complications between the two processing modalities, preservation, and transection of the round ligament of uterus, in adult female inguinal hernia patients undergoing TAPP.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of 84 female patients (117 sides) who underwent TAPP in XXX Hospital from July 2013 to August 2022. Patient characteristics and technical details of the surgical procedure were collected and divided into two groups according to whether the round ligament of uterus was severed intraoperatively or not. There were 52 cases (77 sides) in the group with preservation of the round ligament of uterus and 32 cases (40 sides) in the group with transection of the round ligament of uterus, comparing the general condition, surgical condition, and the occurrence of postoperative related complications between the 2 groups.

Results

The operative time for unilateral primary inguinal hernia was (129.2 ± 35.1) and (89.5 ± 42.6) minutes in the preservation and transection groups, respectively. There were no statistical differences between the two groups in terms of age, length of hospital stay, ASA, BMI, history of lower abdominal surgery, type and side of hernia, intraoperative bleeding, and time to surgery for primary bilateral hernia (P > 0.05). In addition, there was likewise no statistical difference in the occurrence of postoperative Clavien–Dindo classification, VAS, seroma, mesh infection, labia majora edema, chronic pain or abnormal sensation in the inguinal region, and hernia recurrence in the two groups as well (P > 0.05).

Conclusion

There is no evidence that the transection of the round ligament of the uterus during TAPP has an impact on postoperative complications in patients. However, given the important role of the uterine round ligament in the surgical management of patients with uterine prolapse and the high incidence of uterine prolapse in older women, hernia surgeons should also be aware of the need to protect the round ligament of uterus in older women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Based on the embryonic development of the female reproductive system and the anatomy of the inguinal region, which makes the incidence of inguinal hernia in women much smaller than in men [1]. It is estimated that only 8–16% of inguinal hernia repairs occur worldwide each year in female inguinal patients, about 2–3 million times [2]. Therefore, there are fewer research data related to inguinal hernia in women, as well as surgical data. Since laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair was performed in 1990 [3], the processing of the round ligament of uterus has contended. Some hernia surgeons believe that transection of the round ligament of uterus is beneficial to simplify the mesh placement operation [4]. With the improvement of laparoscopic techniques and the recognition of the round ligament of uterus in maintaining the uterus in an anteverted forward position by hernia surgeons, there is a greater tendency to protect the round ligament of uterus [5]. However, intraoperatively, the round ligament of uterus is often found to be adherent to the hernia sac and peritoneum, making the release of the round ligament of uterus from the hernia sac and peritoneum in the anterior peritoneal space a difficult surgical task during the laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal repair of inguinal hernia (TAPP) in women. The question of how to process the round ligament of uterus requires a comprehensive analysis of intraoperative operations and postoperative complications, but there is a lack of studies on whether transection of the round ligament of uterus affects surgical outcomes and increases the incidence of postoperative complications. Therefore, this study reviewed 84 patients (117 sides) with adult female inguinal hernia who voluntarily underwent TAPP in XXX Hospital from July 2013 to August 2022. A retrospective controlled study was conducted to explore whether there was any difference in the efficacy and postoperative complication rate between preservation and transection of the round ligament of uterus during TAPP in adult female inguinal hernia patients.

Materials and methods

Design overview

During the study period, clinical data related to female patients who underwent TAPP in XXX Hospital were retrospectively collected, and the occurrence of postoperative complications was collected by telephone follow-up. They were divided into transection (T group) and preservation (P group) groups according to whether the surgeon performed transection or preservation of the round ligament during TAPP. Finally, a retrospective controlled study was conducted on the collected data. The ethics committee of XXX Hospital approved the retrospective study. Data were accessed anonymously, waiving the requirement for study participant consent. All methods were performed by relevant guidelines and regulations.

Patient selection

Ninety-three cases of all female patients who underwent TAPP in XXX Hospital were collected from July 2013 to August 2022, and finally, 84 cases were successfully followed up. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) female patients aged 30–80 years, (2) patients who underwent TAPP, and (3) patients with intraoperative confirmed inguinal hernia. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with inguinal incarcerated hernia; (2) laparoscopic conversion to open hernia repair in patients; (3) patients with incomplete data; and (4) patients with a history of the previous hysterectomy.

Data collection and evaluation parameters

Data were reviewed from clinical cases, including age, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, body mass index (BMI), history of previous lower abdominal surgery, type and side of hernia, initial or recurrence, length of hospital stay, duration of surgery, whether the round ligament of uterus was transected, and intraoperative bleeding. Postoperative complications were evaluated according to the Clavien–Dindo classification. Patients were followed up by telephone for the occurrence of complications, including whether the seroma occurred, whether mesh infection occurred, whether labia majora edema occurred, whether dysmenorrhea occurred, whether difficulty in urination occurred, whether abnormal sensation or chronic pain in the inguinal region occurred, and whether recurrence of inguinal hernia.

Surgery steps

The surgeries are all performed by different surgical groups in the same center. As a treatment center for hernia diseases, the center often holds academic discussions and organizes standardized surgical classes, and the surgical groups in this center are almost identical in terms of treatment philosophy and surgical technique.

The management of the round ligament is determined by the intraoperative situation. If this procedure is successful and it is easier to separate the ligament from the hernia sac then the ligament will be protected and parietalized. If it is difficult to separate the hernial sac from the uterine ligament or the uterine ligament is inadvertently damaged during the separation of the hernial sac, then a direct transection of the uterine ligament is chosen. However, if the separation of the hernia sac goes smoothly and there is the only difficulty in the parietilisation of the uterine ligament, the Keyhole approach is chosen.

Placement of trocars

After general anesthesia had been induced, a pneumoperitoneum at 12–15 mmHg was created with a Veress needle at the upper edge of the umbilicus, and a 10 mm trocar placed for insertion of a 30° laparoscope. The junction of the external border of the rectus abdominis muscle on the affected side with the horizontal line of the umbilicus and the junction of the external border of the rectus abdominis muscle on the opposite side with the horizontal line below the umbilicus were placed on two 5 mm trocars as the operation holes.

Incision of the peritoneum

The peritoneum was incised in an arc from 2 cm above the internal ring-opening from the medial umbilical fold lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine. The subabdominal vessels are protected, and the peritoneal flaps at the upper and lower margins are freed. Access to the anterior peritoneal space.

Separation of the anterior peritoneal space

After dissecting the peritoneum. Do not rush to separate the hernia sac. Firstly, the gap between its two sides is separated. The lateral gap (lateral to the inferior abdominal wall vessels) is easier to separate, and the incised lateral peritoneal flap is freed inferiorly to the middle level of the iliopsoas muscle, and reveals the lateral edge of the inguinal hernia. Care is taken not to damage the nerves in the "triangle of pain". All operations are performed posteriorly to the transverse abdominal fascia. Next is the separation of the medial space (medial to the inferior abdominal wall vessels) by separating the incised medial peritoneal flap downward and medially into the Retzius’ space, fully exposing the pectineal ligament and pubic symphysis and separating it beyond the midline. The separation of the Retzius' space should be performed in the loose tissue between the transverse abdominal fascia and the umbilical cystic fascia to avoid damage to the bladder; there are important blood vessels within and near the Retzius' space and care should be taken when separating the adhesions between the hernia sac and the round ligament of the uterus.

Separation range

Medially to the pubic symphysis and over the midline, laterally to the iliopsoas muscle and anterior superior iliac spine, superiorly to 2–3 cm above the joint tendon, medially and inferiorly to approximately 2 cm below the pectineal ligament, and externally and inferiorly to approximately 6 cm from the opening of the internal ring.

Management of the round ligament of the uterus

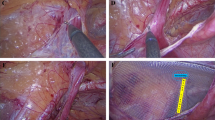

Inner ring opening shaping (Keyhole)

An opening is cut in the mesh so that the round ligament of the uterus passes through it. The mesh is laid flat between the round ligament of the uterus and the abdominal wall. Finally, the mesh opening is closed with a non-absorbable suture, taking care to protect the uterine ligament from compression (Fig. 1).

Transection of the round ligament of the uterus

The location of the transection of the uterine round ligament was within 1 cm of the inner ring opening and 1 cm of the lower boundary of the separation range. After closing the uterine round ligament with a bioclip, the uterine round ligament was cut with electric scissors at a distance of 0.5 cm from the bioclip.

Mesh placement

The area covered by the mesh is the area of separation of the anterior peritoneal space as described above. In case of a bilateral hernia, the two meshes should be crossed and overlapped at the midline. The inner lower part of the mesh should be placed in the Retzius' space and the outer lower part should be more than 0.5 cm away from the peritoneum to avoid recurrence of herniation due to curling below the mesh.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 18.0 for Windows was used for statistical analysis. The measurement data were expressed as mean and standard deviation using t-test and variance analysis. Enumeration data were analyzed using the χ 2 test. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient general information

As shown in Table 1, a total of 84 female patients undergoing TAPP were collected, including 42 with preservation of the round ligament of uterus of the uterus and 32 with transection. There were no statistical differences between the two groups in terms of age, ASA, BMI, hospital days, history of lower abdominal surgery, and follow-up time.

Patient surgery

As shown in Table 2, there was no statistical difference between the two groups in terms of hernia type and side, intraoperative bleeding, and operative time for bilateral primary hernia, but there was a statistical difference between the operative time for unilateral primary hernia in the P group (129.2 ± 35.1 min) and the T group (89.5 ± 42.6 min), P < 0.05.

Postoperative complications, hernia recurrence follow-up

As shown in Table 3, there were 20 cases of Grade I in the Clavien-Dindo classification in group P, of which 23 sides had chronic pain or sensory abnormalities in the inguinal region after surgery, and 7 cases of Grade I in the Clavien–Dindo classification in group T, of which 2 sides had seroma in the inguinal region after surgery; 23 The patients on one side had chronic pain or sensory abnormalities in the inguinal region after surgery. No postoperative mesh infection, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, labia majora edema, or hernia recurrence occurred in either group. There were no statistically significant differences in postoperative VAS, Clavien–Dindo classification, seroma, chronic pain, or sensory abnormalities in the groin area in either group.

Discussion

Compared with conventional open hernia repair, laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (LIHR) has the advantage of a shorter hospital stay, a lower recurrence rate and a lower incidence of various complications such as chronic pain [6], and is recommended by international inguinal hernia guidelines as the procedure of choice for the treatment of female inguinal hernia [7]. One of the basic principles of successful LIHR is to place the mesh directly on the abdominal wall. Intraoperatively, the round ligament of uterus is an important factor affecting the smooth placement of the mesh on the abdominal wall, and the intraoperative management of the round ligament of uterus is aimed at smoothly fitting the mesh directly to the abdominal wall. The parietilisation is the basic intraoperative operation for the management of the round ligament of uterus, but it is sometimes difficult due to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), uterine pathology, previous surgery, and other factors that cause severe adhesions between the round ligament and the peritoneum.

There is no unified and definitive opinion on how the round ligament of uterus of the uterus should be treated during TAPP. Proponents of transection argue that the round ligament of uterus is often adherent to the hernia sac and peritoneum in the anterior peritoneal space, making separation difficult [8], and that forced separation may result in damage to the peritoneum and the round ligament of uterus, resulting in significant bleeding that is not worth. Transection of the round ligament of uterus may facilitate the placement of the mesh to some extent [9]. On the other hand, the preservation side believes that the bilateral round ligament of uterus has a certain role in maintaining the uterus in an anteversion position, preventing uterine prolapse and blood supply during pregnancy [10] and that a decrease in the tension of the round ligament of uterus will have an impact on maintaining the uterus in anteversion position, which may cause uterine prolapse and difficulty in urination in women [11]. Based on these two views, there is a lack of awareness of the protection of the round ligament of uterus in middle-aged and elderly female patients without fertility requirements in LIHR [4]. There are fewer studies on whether transection of the round ligament of uterus during TAPP has an impact on surgical outcomes and recent postoperative complications. Hernia surgeons prefer to protect the round ligament of uterus in young unmarried women and to eliminate bias due to this aspect of the concept, female inguinal hernia patients aged 30–80 years were included in this study. The results showed that in female inguinal hernia patients undergoing TAPP, there was no statistical difference between preserving and transecting the round ligament of uterus in terms of postoperative complications such as: seroma, mesh infection, labia majora edema, chronic pain, sensory abnormalities and hernia recurrence in the inguinal region, but the operative time for unilateral primary inguinal hernia was longer in preservation group than transection group. For bilateral primary inguinal hernias, the result of no statistical difference in operative time between the two groups may be biased by the low number of bilateral inguinal hernia TAPP procedures in the transection group. The present study confirms that the presence or absence of the round ligament of uterus during TAPP does not significantly affect the surgical outcome or the incidence of postoperative complications. The results are consistent with the characteristics of the female TAPP procedure and the following knowledge of the embryonic developmental process, anatomy, and physiological function of the round ligament of uterus.

Reviewing the anatomy and physiology of the round ligament of uterus, it is a round cord-like ligament of about 10–12 cm in length composed of smooth muscle and connective tissue, in which the smooth muscle is autonomously rhythmic and direct or indirect stimulation can cause contraction of the round ligament of uterus [12], which has a role in fetal output during labor. For the starting point of the round ligament of the uterus, most scholars believe that it starts with the uterine horn, while for its termination point, the conclusions of different scholars are not uniform [13]. There is little vascular distribution around the round ligament of uterus [14], and only a few lymphatic vessels are present inside [15]. Reviewing the embryonic development of the round ligament of uterus, a gubernaculum structure is formed at the caudal end of the ovary during the 8th–17th weeks of female fetal embryonic development and connects the ovary to the inguinal region tissue. This structure crosses the mesonephric duct during ovarian descent and fuses with the wall of the uterus at the entry point of the fallopian tube. The cephalic end of this gubernaculum structure develops as the proper ligament of ovary, the caudal end develops as the round ligament of uterus, and the primitive mesenchymal tissue within the intermediate mesoderm between the cephalic ends of the ovary develops as the ovarian suspensory ligament [16]. That is, both the round ligament of uterus and the proper ligament of ovary originate from the same gubernaculum structure and only partially heal to the uterus during development. The round ligament of uterus, like other ligamentous structures that hold the uterus in place, is important in maintaining the position of the uterus.

Even though studies have shown that the uterine ligament does not play a major role in the development and progression of uterine prolapse and does not affect fertility [17,18,19], there is a lack of multicenter, retrospective clinical studies with large samples and a need for long-term follow-up and review. To date, it is uncertain whether transection of the uterine round ligament has a significant effect on fertility and the incidence of uterine prolapse in female patients. Until higher quality clinical studies are available, the TAPP procedure is still worth the effort and time to protect the round ligament of the uterus.

Of concern is that in older women, the uterine prolapse has a higher incidence [20] and the round ligament of uterus has an important role in the surgical treatment of uterine prolapse [21]. It is the ideal body structure, and an intact set of round ligaments can be of great help in treatment of uterine prolapse. Although synthetic and biomaterials can be used in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction disorders, such as uterine prolapse, possibly they can lead to a series of serious complications such as polypropylene meshes that can lead to mesh erosion, exposure, pain and inflammation, while biopatches have poor mechanical properties and degrade rapidly, leading to poor anatomical reduction, which in turn limits their clinical use [22]. Hernia surgeons should be proactive in protecting the round ligament of uterus. As much as possible, inguinal hernia repair in female patients should be performed to protect the round ligament of uterus for possible subsequent uterine prolapse surgery.

With the improvement of surgical techniques, some methods of preserving the round ligament of uterus have gradually matured and been skillfully applied in TAPP. The main surgical approaches to preserve the round ligament in inguinal hernia surgery are the inner ring mouth shaping (Keyhole) and T-shaped incision of the peritoneum with sutures [23], compared with the Keyhole method, which has obvious significance for protecting the peritoneum. However, this surgical approach destroys the integrity of the mesh and the round ligament of the uterus passes through which amounts to a new abdominal wall defect with the possibility of recurrence of the inguinal hernia after surgery. Our team found that the use of self-fixing meshes in the "Y" shaped laying method has some advantages over the conventional laying method as it can effectively shorten the laying time of the self-fixing mesh without increasing the risk of complications [24] (Fig. 2).

Self-fixing mesh "Y" lay-up method. a The round ligament of uterus is placed at the root of the "Y" bifurcation of the mesh in the TAPP, b The left half of the mesh is unfolded to the left in the TAPP, c The right half of the curled mesh is laid flat in the TAPP, d The mesh cut-out is sutured in the TAPP

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is no evidence that the transection of the uterine round ligament during TAPP affects the development of postoperative complications in patients. However, considering the important role of the uterine round ligament in the surgical management of patients with uterine prolapse and the higher incidence of uterine prolapse in older women. Hernia surgeons should be more aware of the need to protect the round ligament of uterus in older women.

Data availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

04 October 2023

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-023-02906-9

References

Kark AE, Kurzer M (2008) Groin hernias in women. J hernias abdominal wall surg. 12(3):267–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-007-0330-4

Weber A, Valencia S, Garteiz D, Burguess A (2001) Epidemology of hernias in the female. In: Bendavid R, Abra-hamson J, Arregui ME, Flament JB, Phillips EH (eds) Abdominal wall hernias: principles and processing. Springer, New York, New York

Neumayer L, Giobbie-Hurder A, Jonasson O, Fitzgibbons R Jr, Dunlop D, Gibbs J, Reda D, Henderson W, Program VACS (2004) Open mesh versus laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia. N EnglJ Med. 350(18):1819–1827. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa040093

Luk Y, Chau PL, Law TT, Ng L, Wong KY (2021) Laparoscopic total extraperitoneal groin hernia repair in females: comparison of outcomes between preservation or division of the uterine round ligament. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 31(1):6–10. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2020.0270

Schmidt L, Andresen K, Öberg S, Rosenberg J (2018) Dealing with the round ligament of uterus in laparoscopic groin hernia repair: a nationwide survey among experienced surgeons. Hernia j hernias abdom wall surg 22(5):849–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1802-4

O’Reilly EA, Burke JP, O’Connell PR (2012) A meta-analysis of surgical morbidity and recurrence after laparoscopic and open repair of primary unilateral inguinal hernia. Ann Surg 255(5):846–853. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824e96cf

Hernia Surge Group (2018) International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia j hernias abdominal wall surg 22(1):1–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x

Cobb WS (2013) Technique: laparoscopic TAPP and IPOM. In: Jacob BP, Ramshaw B (eds) The SAGES manual of hernia repair. Springer, New York New York

Claus C, Cavazolla LT, Furtado M, Malcher F, Felix E (2021) Challenges To The 10 golden rules for a safe minimally invasive surgery (mis) inguinal hernia repair: can we improve? Arquivos brasileiros de cirurgia digestive. 34(2):1597. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-672020210002e1597

Mollaeian M, Mollaeian A, Ghavami-Adel M, Abdullahi A, Torabi B (2012) Preserving the continuity of round ligament along with hernia sac in indirect inguinal hernia repair in female children does not increase the recurrence rate of hernia Experience with 217 cases. Pediat surg int 28(4):363–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-011-3025-y

Fauconnier A, Dubuisson JB, Foulot H, Deyrolles C, Sarrot F, Laveyssière MN, Jansé-Marec J, Bréart G (2006) Mobile uterine retroversion is associated with dyspareunia and dysmenorrhea in an unselected population of women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 127(2):252–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.11.026

Chaudhry SR, Chaudhry K (2022) Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis. StatPearls Publishing, Uterus Round Ligament. In StatPearls

Bellier A, Cavalié G, Marnas G, Chaffanjon P (2018) The round ligament of the uterus Questioning its distal insertion. Morphologie bulletin Associat des anat. 102(337):55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.morpho.2018.04.001

Hebert J, Jagtiani M, Hsu A, Schmelzer D, Wolodiger F (2017) Exploring a third confirmed case of hemoperitoneum following open inguinal hernia repair caused by sampson artery hemorrhage. Case reports surg 2017:1487526. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1487526

Kleppe M, Kraima AC, Kruitwagen RF, Van Gorp T, Smit NN, van Munsteren JC, DeRuiter MC (2015) Understanding lymphatic drainage pathways of the ovaries to predict sites for sentinel nodes in ovarian cancer. Int j gynecol cancer 25(8):1405–1414. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000514

Acién P, Sánchez del Campo F, Mayol MJ, Acién M (2011) The female gubernaculum: role in the embryology and development of the genital tract and in the possible genesis of malformations. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 159(2):426–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.07.040

Martins P, Silva-Filho AL, Fonseca AM, Santos A, Santos L, Mascarenhas T, Jorge RM, Ferreira AM (2013) Strength of round and uterosacral ligaments: a biomechanical study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 287(2):313–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-012-2564-3

Yen CF, Wang CJ, Lin SL, Lee CL, Soong YK (2002) Combined laparoscopic uterosacral and round ligament procedures for treatment of symptomatic uterine retroversion and mild uterine decensus. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 9:359–366

Liu Y, Liu J, Xu Q, Zhang B, Wang M, Zhang G, Yan Z (2022) Objective follow-up after transection of uterine round ligament during laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernias in women: assessment of safety and long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc 36(6):3798–3804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08696-4

Doshani A, Teo RE, Mayne CJ, Tincello DG (2007) Uterine prolapse. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 335(7624):819–823. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39356.604074.BE

Lin LL, Ho MH, Haessler AL, Betson LH, Alinsod RM, Liu CY, Bhatia NN (2005) A review of laparoscopic uterine suspension procedures for uterine preservation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 17:541–546

Lin M, Lu Y, Chen J (2022) Tissue-engineered repair material for pelvic floor dysfunction. Front bioeng biotechnol. 10:968482. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.968482

He Z, Hao X, Feng B, Li J, Sun J, Xue P, Yue F, Yan X, Wang J, Zheng M (2019) Laparoscopic Repair for Groin Hernias in Female Patients: A Single-Center Experience in 15 Years. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 29(1):55–59. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2018.0287

Tian L, Zheng B, Geng X, Yang W, Wang X (2021) Application of self fixing mesh with “Y-shaped” placement in laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal repair of inguinal hernia of female inguinal hernia. Clincal Medicine of Chian 37(04):344–348

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZZ and LY conceived and designed the study, and the subsequent statistical analysis. ZZ wrote the article. LY, CT, and LT participated in the revision and review of the article. YL and XZ were involved in the collection of patient data. XY conducted the telephone follow-up of patients and discussion of the study results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

In view of the retrospective nature of the study and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care the Medical Ethics Committee of the Shaanxi Provincial People's Hospital approved the study.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any study with animals performed by any of the authors. All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants of the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-023-02906-9

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Z., Tong, C., Tian, L. et al. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Retrospective study of preservation and transection of the round ligament of uterus during laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair in adult women. Hernia 27, 1195–1202 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-023-02765-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-023-02765-4