Abstract

Globally, seagrass ecosystems are considered major blue carbon sinks and thus indirect contributors to climate change mitigation. Quantitative estimates and multi-scale appraisals of sources that underlie long-term storage of sedimentary carbon are vital for understanding coastal carbon dynamics. Across a tropical–subtropical coastal continuum in the Western Indian Ocean, we estimated organic (Corg) and inorganic (Ccarb) carbon stocks in seagrass sediment. Quantified levels and variability of the two carbon stocks were evaluated with regard to the relative importance of environmental attributes in terms of plant–sediment properties and landscape configuration. The explored seagrass habitats encompassed low to moderate levels of sedimentary Corg (ranging from 0.20 to 1.44% on average depending on species- and site-specific variability) but higher than unvegetated areas (ranging from 0.09 to 0.33% depending on site-specific variability), suggesting that some of the seagrass areas (at tropical Zanzibar in particular) are potentially important as carbon sinks. The amount of sedimentary inorganic carbon as carbonate (Ccarb) clearly corresponded to Corg levels, and as carbonates may represent a carbon source, this could diminish the strength of seagrass sediments as carbon sinks in the region. Partial least squares modelling indicated that variations in sedimentary Corg and Ccarb stocks in seagrass habitats were primarily predicted by sediment density (indicating a negative relationship with the content of carbon stocks) and landscape configuration (indicating a positive effect of seagrass meadow area, relative to the area of other major coastal habitats, on carbon stocks), while seagrass structural complexity also contributed, though to a lesser extent, to model performance. The findings suggest that accurate carbon sink assessments require an understanding of plant–sediment processes as well as better knowledge of how sedimentary carbon dynamics are driven by cross-habitat links and sink–source relationships in a scale-dependent landscape context, which should be a priority for carbon sink conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Understanding the strength and variability of sedimentary carbon storage is crucial for accurately assessing coastal carbon dynamics (Lavery and others 2013; Watanabe and Kuwae 2015) and for developing efficient management strategies to absorb atmospheric CO2, thereby contributing to climate change mitigation (Duarte and others 2011). In recent years, an increasing number of studies have quantified or compiled data on Corg stored in sediment (reviewed by Kennedy and others 2010; Mcleod and others 2011; Alongi 2012), constituting the “blue carbon” of vegetated coastal habitats (that is, salt marshes, mangroves, and seagrass meadows), adding valuable information to global estimates of natural carbon sinks (Fourqurean and others 2012). Contemporary knowledge gained from direct measurements of spatial and regional variability in the Corg stock levels of coastal habitats is growing (Lavery and others 2013), especially for seagrass habitats (for example, Lavery and others 2013; Serrano and others 2014; Miyajima and others 2015; Armitage and Fourqurean 2016; Dahl and others 2016a; Röhr and others 2016; Samper-Villarreal and others 2016). Evidence of the rapid degradation and loss of vegetated blue carbon habitats (Davy and others 2009; Waycott and others 2009; Spalding and others 2010; Mcleod and others 2011; Macreadie and others 2015; Serrano and others 2016a) due to anthropogenic activity stresses the urgent need for widespread assessments of natural blue carbon sinks to spur directed conservation and restoration efforts (Laffoley and Grimsditch 2009; Duarte and others 2013) as well as for predictive modelling of habitat–carbon dynamics under global change (Macreadie and others 2013) linked to accurate estimates of future economic impacts (Pendleton and others 2012).

Seagrass meadows are among the Earth’s most productive aquatic ecosystems (Duarte and Cebrián 1996) and provide efficient habitats for the long-term burial of sedimentary Corg (Smith 1981; Duarte and others 2005, 2010; Serrano and others 2016b), well exceeding the accumulation rates of terrestrial ecosystems (Mateo and others 2006; Mcleod and others 2011). Seagrass meadows are responsible for approximately 10–15% of global oceanic organic carbon storage (Duarte and others 2005; Kennedy and Björk 2009), which is thought to be the highest accumulation rate of blue carbon (Kennedy and others 2010; Mcleod and others 2011), and this carbon is potentially stored in sediment for centuries to millennia (Mateo and others 1997; Serrano and others 2012). The high carbon sink capacity of seagrass systems depends on carbon flow pathways and is linked to multiple intricate processes (Duarte and Cebrián 1996; Cebrian 1999). Carbon dioxide is captured by seagrasses (and algae) through photosynthesis, and the extent to which plant biomass accumulates as decay-resistant refractory matter is determined by the fate of plant primary production (that is, grazing, export, and burial; Cebrian 1999). Most seagrass meadows are net autotrophic systems (with gross primary production exceeding respiration; Duarte and others 2010) in which the photosynthetic activity supports high net primary production and efficient sequestration of carbon biomass. The proportion of seagrass biomass that accumulates as Corg stored in sediment depends on a low decomposition rate (Duarte and others 2011), as favoured by low oxygen levels (Barko and Smart 1983), although degradation continues even under anoxic conditions (Canfield and others 1993; Canfield 1994). High belowground biomass could potentially increase sedimentary Corg storage due to correspondingly high root production and rapid turnover (Duarte and others 1998). Along with the metabolic source of sedimentary Corg from seagrass tissue (Duarte and others 2011), seagrass canopies also trap suspended organic matter, retaining it in the sediment as accumulated organic matter (Hendriks and others 2008; Kennedy and others 2010). The efficiency with which seagrass sediment stores Corg is greatly influenced by its properties, such as density, porosity, and grain size (Avnimelech and others 2001; Dahl and others 2016a). Carbon sequestration and storage capacity are therefore driven partly by processes influencing the amount of derived allochthonous (that is, terrestrial and oceanic) carbon in seagrass sediment (Agawin and Duarte 2002) and partly by sediment composition.

The level of Corg stored in seagrass sediment can vary considerably among seagrass habitats (Lavery and others 2013; Alongi and others 2015), depending on multiple interrelated biogeochemical and physical factors operating at a range of scales (for example, Watanabe and Kuwae 2015; Samper-Villarreal and others 2016). Some recent studies have emphasized that the strength of processes responsible for the accumulation of blue carbon stocks (Duarte and Cebrián 1996; Kennedy and others 2010; Duarte and others 2011) is influenced by variables such as structural complexity (Trevathan-Tackett and others 2015), nutrient dynamics (Armitage and Fourqurean 2016), hydrodynamics (Samper-Villarreal and others 2016), water depth (Serrano and others 2014), small-scale patch heterogeneity (Ricart and others 2015), and size of the meadow (Ricart and others 2017). Such cause–effect links are important to understand when assessing seagrass carbon storage over broader geographical ranges to improve management at both local and regional levels (Lavery and others 2013; Macreadie and others 2013). To date, comparatively few studies have explored the relative contribution of multiple factors to patterns of variability in Corg storage in seagrass sediment (for example, Samper-Villarreal and others 2016), with even fewer exploring the influence of factors at scales ranging from the local to landscape levels.

The notion of seagrass meadows as carbon sinks has generally been based on their ability to accumulate organic carbon in the sediment, while the importance of inorganic sedimentary carbon as carbonate (Ccarb) for their carbon sink function has until recently received little attention (Mazarrasa and others 2015). In fact, tropical seagrass meadows can harbour significant amounts of calcifiers, especially solitary green calcareous macroalgae such as Halimeda spp. (Gullström and others 2006) and coralline algal crusts living epiphytically on seagrass leaves (Walker and Woelkerling 1988). There are also reports that seagrasses might develop carbonate structures within their leaves (Enríquez and Schubert 2014). Such within-meadow carbonate production is promoted by the photosynthetic activities of the seagrasses themselves (Semesi and others 2009), partly counteracting the sequestration of carbon in the system. This is because while the calcification process precipitates CaCO3, it simultaneously reduces the seawater pH, driving CO2 from the water column to the atmosphere (Frankignoulle and Gattuso 1993). The amount of carbon lost from seawater as CO2 in proportion to the amount of carbon precipitated as CaCO3 depends on the buffering capacity of the water and is highly variable in marine plant systems. On average, this has been estimated to be approximately 0.6 in “normal” seawater (Ware and others 1992), so that for every mol of CaCO3 formed, pH decreases, resulting in the eventual release of approximately 0.6 mol of CO2 to the atmosphere. The large amounts of CaCO3 in the sediment of many seagrass meadows (Mazarrasa and others 2015) undoubtedly constitute a major carbon stock; parts of this stock could, however, be considered a source of CO2, as suggested earlier by, for example, Mateo and Serrano (2012). Thus, to understand net carbon sequestration rates in seagrass meadows, the strength and variability of both primary productivity and within-meadow calcification must be considered.

Geographical comparison across the globe indicates that estimates of sedimentary blue carbon in seagrass habitats are clearly regionally biased (Duarte and others 2011), with the coastal zone of the Western Indian Ocean (WIO) region being nearly unexplored (compare Dahl and others 2016b). In the WIO, seagrass is a significant habitat engineer of nearshore coastal waters with 14 known seagrass species represented (Gullström and others 2002; Duarte and others 2012) and widespread meadows potentially containing extensive blue carbon-rich seagrass habitats. In the present study, we assessed the natural variability of sedimentary Corg and Ccarb stocks in seagrass meadows, focusing on habitat-building species in locations spread along the East African coast from tropical Tanzania to subtropical areas of southern Mozambique. Using partial least squares (PLS) modelling, we explored the relative importance of environmental attributes at different spatial scales (that is, metre-level within-meadow patch scale and km-level landscape scale). Specifically, we assessed the influence of (1) plant structure (for example, seagrass canopy height and above- and belowground seagrass biomass), (2) nutrients in plants (that is, nitrogen and carbon in leaves or in the root–rhizome complex), (3) sediment properties (that is, sediment density and porosity), and (4) landscape configuration and composition (for example, area of nearby habitats and distance to mangroves or open ocean) on sedimentary Corg and Ccarb in seagrass meadows.

Materials and Methods

Study Areas

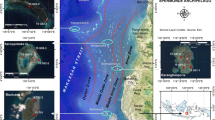

The study was carried out in three major areas on the East African coast, namely Zanzibar (Unguja Island) belonging to Tanzania (6°02-19′S, 39°12-27′E), mainland Tanzania (6°28-48′S, 38°58′-39°18′E), and Inhaca Island, southern Mozambique (25°59′-26°02′S, 32°55-56′E), between January and June 2012. At each location, the sampling was performed in the upper subtidal in seagrass meadows dominated by Enhalus acoroides, Thalassodendron ciliatum, Thalassia hemprichii, or Cymodocea rotundata/serrulata as well as unvegetated areas near the studied seagrass meadows. Four sites were sampled in Zanzibar—Pongwe, Chwaka Bay, Mbweni (here called ZanMbweni), and Fumba; three sites on the mainland coast of Tanzania—Mbegani, Ocean Road, and Mbweni (here called MainMbweni); and two sites on Inhaca Island—Sangala and Saco (Figure 1).

Sampling of Sediment, Seagrass Biomass, and Biometric Data

At every site, six sediment cores were collected (at least 50 m apart) using a push corer (ø = 8 cm, h = 50 or 100 cm) in the middle of each seagrass habitat and adjacent unvegetated area. The sediment cores were sliced and divided into three depth sections: 0–5, 5–25, and 25–50 cm or deeper at some locations (to a maximum of 86 cm). As sediment compaction might influence the relative content of sedimentary carbon (Glew and others 2001), this was assessed by recording the difference in length from the upper part of the core to the sediment surface, inside and outside the corer, when pressed down into the sediment. This core shortening was calculated to be on average 14.6 ± 9.9% (±SD) and has been corrected for in the data. The sediment was homogenized and cleaned of larger shells, infauna, and plant material before drying. A subsample of 60 mL for each depth section was dried at 60°C for approximately 48 h until the weight had stabilized. Sediment density (g DW mL−1) was calculated by dividing sediment dry weight with the volume of the sediment (Supplementary Table 1). Porosity of the sediment (%) was estimated by calculating water content in the sediment by subtracting the wet weight from the dry weight of the sediment (Supplementary Table 1). Material for seagrass biomass and biometric assessments was collected near (<10 m) each core sampled in the seagrass meadows. Three biomass samples were collected using a closed quadrat (0.25 × 0.25 m) randomly placed around the sediment core. Before seagrass biomass collection, the number of shoots was counted in each quadrat. The biomass samples were washed and cleaned of epiphytes and then separated into above- and belowground biomass before being dried at 60°C for 24–48 h until the samples reached constant weight. A larger quadrat of 0.5 × 0.5 m was used to estimate the percentage seagrass cover (n = 10). Shoot height (mm) was determined by random measures of 20 shoots around each sediment core. For details on seagrass-related data, see Supplementary Table 2.

Sediment and Biomass Carbon and Nitrogen Analysis

Each dried sediment sample (see above) was further homogenized by grinding with a mortar and pestle before carbon and nitrogen analysis in an organic elemental analyser (model CHNS-932; Leco, Saint Joseph, MI, USA) (Verardo and others 1990). Each sediment sample was divided into two subsamples for analysis of the total carbon and Corg contents (as percentage of sediment DW). The subsample for Corg determination was pre-treated with 1 and 3 M aqueous hydrochloric acid (HCl) to remove the Ccarb and was dried before analysis. The Ccarb content was then determined from the difference between the total carbon and Corg contents. To estimate areal carbon stocks (g DW m−2), we calculated the total mass of carbon (that is, Corg and Ccarb in grams) per square meter as a function of the depth at the base of each depth section. These Corg and Ccarb values were then used to perform a linear regression as a function of sediment depth. We finally extracted Corg and Ccarb values at a depth of 50 cm according to the regression line. This procedure was performed separately for each habitat in every study site. The seagrass biomass samples were ground; carbon and nitrogen were then separately analysed in the above- and belowground plant parts using the organic elemental analyser (Supplementary Table 2).

Landscape and Habitat Mapping Using Remote Sensing and GIS

The landscape composition and configuration were mapped for each site according to the protocol outlined by Knudby and others (2014), briefly summarized below. For each site, 16 spectral and spatial features were extracted from a Landsat satellite image for n georeferenced field observations divided into nine pre-defined habitat types (that is, coral, seagrass < 40% cover, seagrass ≥ 40% cover, algae, pavement, sand, optically deep water, land, and mangrove). Field observations that were tidally mismatched (for example, coral misidentified as terrestrial in the image) or covered by cloud or cloud shadow were removed, after which a random forest classifier was calibrated and applied to the parts of the image unaffected by cloud or cloud shadow, producing a partial habitat map. Repeating this process with i satellite images covering the site produced i partial habitat maps, each based on an image with a unique combination of cloud cover (below which habitat cannot be mapped), tidal stage, water quality, and sea surface state. These were then combined into a single complete habitat map using a voting procedure in which each image pixel was assigned the habitat type most frequently observed in the partial habitat maps. Map accuracy was quantified using the overall accuracy, based on tenfold cross-validation, which randomly splits the full dataset into 10 subsets of equal size and then uses each subset in turn as validation data and the rest as calibration data (Efron and Gong 1983; Efron and Tibshirani 1994). Three maps were finally produced: one for Zanzibar (n = 1309, i = 20, accuracy = 0.70), one for mainland Tanzania (n = 6592, i = 59, accuracy = 0.68), and one for Inhaca Island (n = 587, i = 17, accuracy = 0.78).

Various spatial metrics, comprising both distance- and area-based measurements at the landscape scale (Table 1), were derived from the image-based habitat maps using ArcGIS 10.4 software (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA). Landscape units were produced using radial buffer zones spatially delimited with diameters of 400 m, 1 km, or 5 km. Distances to mangrove and to open ocean (> 10 m depth) were measured from the centroid of the buffer zone to the edge of the selected habitat, while habitat area was assessed within the buffer zone of the landscape unit. Landscape boundaries were not overlapping. Landscape unit sizes were chosen to represent relevant spatial scales to cover potential carbon exchange within the coastal landscape.

Data Analyses

Spatial variations in sedimentary Corg and Ccarb contents among habitats and across sites were tested separately (as all habitats were not found in all sites; see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2) using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Before the analyses, the assumption of homogeneity of variance was checked using Levene’s test, and when necessary the data were log10(x + 1) transformed. In scale-dependent analyses (at metre-level patch scale and km-level landscape scale), the relative importance of environmental predictors (Table 1) for the sedimentary Corg and Ccarb contents of seagrass habitats was assessed by modelling projections to latent structures (that is, variables with the best predictive power) by means of partial least squares (PLS) regression analysis (Wold and others 2001) on untransformed data using SIMCA 13.0.3 software (UMETRICS, Malmö, Sweden). PLS modelling is particularly applicable when the number of predictor variables is large and when one must deal with multi-collinearity. This type of regression technique is useful for applications with ecological data (Carrascal and others 2009).

Results

Variability of Sedimentary Corg Stocks

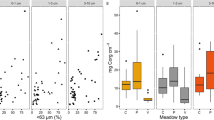

Seagrass habitats had higher mean sedimentary Corg stock levels than did nearby unvegetated habitats in all sites except Mbegani (Figures 2, 3A; Supplementary Table 1). The mean Corg storage in seagrass sediment ranged from 2134 to 7305 g m−2 and was up to about five times the levels in nearby unvegetated sediments (ranging from 740–2610 g m−2) (Figure 3A). When comparing habitats, there was a clear difference in mean sedimentary Corg stock levels (ANOVA, F 4,204 = 25.17, p < 0.001; Figure 2). A significantly higher Corg content was found in E. acoroides meadows than in T. hemprichii (Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.05) or Cymodocea spp. (p < 0.01) meadows, though the Corg content did not significantly differ from that in T. ciliatum meadows. The Corg contents in T. ciliatum, T. hemprichii, and Cymodocea spp. meadows did not differ significantly from each other (Tukey’s HSD test, p = 0.22–0.82). Unvegetated habitats had clearly lower sedimentary Corg contents than did any seagrass habitats (Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.001 for all pairwise tests). As with the habitat comparison, an across-site analysis of mean Corg in seagrass sediment also indicated clear variability (ANOVA, F 8,147 = 20.50, p < 0.001; Figure 3A). In general, the sedimentary Corg content in seagrass habitats was higher in most tropical sites (that is, in Zanzibar and mainland Tanzania) than in subtropical sites (that is, Sangala and Saco in Mozambique), with the highest average levels found in Chwaka Bay, followed by Pongwe, ZanMbweni, and Fumba (all sites in Zanzibar) (Figure 3A). Regarding the vertical distribution of sedimentary Corg, no clear patterns of variability could be discerned in the depth profiles (Supplementary Figure 1). At most sites, however, the sedimentary Corg content was higher in the various sediment depth layers in seagrass habitats than in unvegetated areas (Supplementary Figure 1).

Mean (±SE) organic carbon (Corg) and inorganic carbon (Ccarb) in sediments in seagrass meadows (with seagrasses separated at the species/genus level) and unvegetated areas with the various study sites (Figure 1) pooled. The Corg and Ccarb values are based on linear regression calculations (Corg or Ccarb as a function of depth) to a sediment depth of 50 cm. Note that all habitats were not found in all sites (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Mean (±SE) organic carbon (Corg) and inorganic carbon (Ccarb) in sediments in seagrass meadows (with the various seagrasses, that is, Th, Ea, Tc, and Cym spp., merged; for seagrass name abbreviations, see Figure 2) and unvegetated areas across all study sites (see Figure 1 for site locations). The Corg and Ccarb values are based on linear regression calculations (Corg or Ccarb as a function of depth) to a sediment depth of 50 cm.

Variability of Sedimentary Ccarb Stocks

In general, in the sediment, the mean Ccarb level (31,071 ± 4131 g m−2; mean ± SE) was considerably higher (4–16 times depending on habitat type) than the mean Corg level (3498 ± 259 g m−2; mean ± SE) (Figure 2). As found for the sedimentary Corg, the mean sedimentary Ccarb stock was higher in most seagrass habitats and sites (ranging from 5585 to 85,478 g m−2) than in nearby unvegetated areas (ranging from 1800 to 88,951 g m−2) (Figures 2, 3B). An among-habitat comparison revealed clear differences in sedimentary Ccarb among seagrass habitats (ANOVA, F 4,204 = 8.22, p < 0.05; Figure 2). The mean sedimentary Ccarb content was clearly lower in Cymodocea spp. meadows and unvegetated areas than in the three other seagrass habitats (Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.05 to p < 0.001; Figure 2), which themselves did not differ from each other (Tukey’s HSD test, p = 0.11–0.91). Unvegetated habitats had a higher mean sedimentary Ccarb level than did meadows dominated by Cymodocea spp. (Figure 2), but this difference was not significant (Tukey’s HSD test, p = 0.12). The mean Ccarb in sediment differed significantly among sites (ANOVA, F 8,147 = 88.14, p < 0.001; Figure 3B). In general, the sedimentary Ccarb content was markedly higher in the four sites in Zanzibar (that is, Pongwe, Chwaka, ZanMbweni, and Fumba) than in the sites on the Tanzanian mainland (that is, Mbegani, MainMbweni, and Ocean road) and Inhaca Island (that is, Sangala and Saco) (Figure 3B). As found for Corg, the depth profiles of sedimentary Ccarb displayed no clear trends of variation, with a generally (but not consistently) higher sedimentary Ccarb content in seagrass habitats than in unvegetated areas (Supplementary Figure 2).

Correlations Between Sedimentary Corg and Ccarb Stocks

In all habitats, there were positive correlations between the amounts of sedimentary Corg and Ccarb (p < 0.05), with a Ccarb:Corg ratio ranging from 1.8 in the subtropics (Sangala) to 15.9 in tropical Zanzibar (Pongwe) (Figure 4). Strong correlative relationships were found between sedimentary Corg and Ccarb in seagrass meadows composed of E. acoroides (R 2 = 0.89; Figure 4A) and Cymodocea spp. (R 2 = 0.76; Figure 4D), while the relationships were slightly less strong in meadows composed of T. hemprichii and T. ciliatum (R 2 = 0.63 and 0.45, respectively; Figure 4C, B). The relationship between Corg and Ccarb content was the weakest in sediment from unvegetated areas (R 2 = 0.36; Figure 4E).

Relationships between organic carbon (Corg) and inorganic carbon (Ccarb) in sediment from seagrass meadows (with seagrasses separated at the species/genus level; for full seagrass names, see Figure 2) and unvegetated areas, with the various study sites (Figure 1) pooled. The Corg and Ccarb values are based on linear regression calculations (Corg or Ccarb as a function of depth) to a sediment depth of 50 cm.

PLS Modelling Performance

All four PLS models indicated relationships between selected environmental metrics and the sedimentary Corg or Ccarb content (Figure 5). The cross-validated variance (Q2 statistics) of the models ranged from 20 to 76%, which is higher than the significant limit level of 5%, so all models displayed high or relatively high predictability. The cumulative fraction of all predictor variables combined (R2y cum) in the models explained between 51 and 99% of the variation, so the models displayed a high degree of determination and fit.

Coefficient plots of partial least squares (PLS) regression models of organic carbon (Corg) and inorganic carbon (Ccarb) contents (%) in seagrass sediment (all studied seagrass species combined) at the patch (A, B) and landscape (C, D) scales. Predictor variables are ranked in order of importance from left (most influential) to right (least influential). Grey bars represent predictors with VIP (variable influence on the projection) values above 1, which are those variables that have an above average influence on the response variable (that is, Corg and Ccarb stocks), whereas white bars are those variables contributing less than average to the overall model. Note that BgDW in (A) is above 1. See Table 1 for abbreviations.

Influence of Environmental Predictors on Sedimentary Corg Content

Sedimentary Corg content in seagrass habitats was strongly negatively correlated with sediment density, which was the most important predictor in models at both the patch and landscape scales (Figure 5A, C). Belowground seagrass biomass was positively correlated with sedimentary Corg content, although it was a less strong predictor than was sediment density (Figure 5A, C). Aboveground seagrass biomass and sediment porosity were also positively correlated with sedimentary Corg content, but contributed moderately or weakly to the performance of models (Figure 5A, C). Several landscape variables seem to be important for the sedimentary Corg content in seagrass meadows, including area of mangrove (negatively correlated), area of unvegetated sediment (negatively correlated), and seagrass area (positively correlated) (Figure 5C).

Influence of Environmental Predictors on Sedimentary Ccarb Content

As found in the Corg model analyses, the primary predictor of sedimentary Ccarb content in seagrass habitats was sediment density, which was strongly negatively associated with the level of Ccarb (Figure 5B, D). Seagrass shoot density (negatively correlated) and canopy height (positively correlated) were important predictors in the patch-scale model (Figure 5B). From a landscape-scale perspective, areas of mangrove and of unvegetated sediment were strongly negatively related to sedimentary Ccarb content (Figure 5D). Sediment porosity (positively correlated) contributed moderately to the model performance at landscape scale (Figure 5D).

Discussion

Our spatially widespread survey (across a tropical–subtropical coastal continuum) indicated that the patterns of variability in sedimentary Corg and Ccarb in seagrass habitats were largely related to sediment properties and partly related to seagrass structural complexity. We found low to moderate Corg and Ccarb contents in the seagrass sediments. The levels of these two carbon pools corresponded well to each other, indicating that the capture of organic carbon is linked to calcification at a broad spatial scale across latitudes. The findings further indicated the strong influence of the spatial arrangement of the coastal landscape, with higher levels of Corg and Ccarb stored in seagrass sediment within landscapes comprising large areas of seagrass meadows, relative to other major coastal habitats (that is, mangrove forest and unvegetated areas). When attempting to predict the sedimentary carbon sink capacity of tropical coasts, it is therefore important not only to understand the intricate plant–sediment (or plant–plant) processes but also to envision how the mechanisms underlying cross-habitat carbon exchange may vary in the context of larger, km-scale landscapes with differing configurations and compositions.

The present survey is the first major study focusing on seagrass blue carbon of the Western Indian Ocean and showed that seagrass habitats in this region can be important Corg sinks, with sedimentary carbon levels ranging from 0.20 to 1.44% on average, matching those found in previous studies (Lavery and others 2013; Rozaimi and others 2016; Samper-Villarreal and others 2016), but lower than the global mean of 2.0% (median of 1.4%) reported by Fourqurean and others (2012). Clear differences were seen among seagrass habitats, with the highest sedimentary Corg stocks found in meadows composed of the largest seagrass species, and meadows dominated by smaller species in turn having higher sedimentary Corg than do unvegetated areas. This emphasizes the influence of the intrinsic properties of the seagrass species themselves—depending, for example, on variation in morphology and/or biomass—on the sedimentary Corg storage capacity. Sediment Corg stocks also varied across the region, with the highest levels found in tropical seagrass meadows and lowest levels in the subtropical area. There is, however, considerable variation within the tropical region, with some sites having substantially higher sedimentary Corg contents and others having levels equalling those of the subtropical sites. This suggests an influence of large-scale factors such as surrounding environmental conditions and landscape structure.

As clearly indicated by the PLS models, sedimentary Corg stock levels were strongly negatively linked to sediment density and to some extent positively linked to porosity in seagrass habitats. These associations have previously been established in a range of sediments (Avnimelech and others 2001), including temperate seagrass sediments (Dahl and others 2016a; Röhr and others 2016). Higher Corg storage in seagrass sediment is therefore related to less sediment compaction and higher sediment porosity. The remineralization process in which organic matter is sequestered into the long-term storage of decay-resistant refractory carbon is also related to the belowground seagrass biomass. In accordance with this, belowground seagrass biomass was found to be a significant variable in the PLS models, being positively related to sedimentary Corg content. This relationship is expected, given that high primary production will benefit the accumulation of refractory Corg in the sediment (Cebrian 1999) and that the root–rhizome system often dominates the total seagrass plant biomass (Duarte and Chiscano 1999). In addition, high root production and turnover can contribute significantly to overall seagrass production (Duarte and others 1998). This results in the high inflow of decay-resistant detritus because of a high content of nutrient-poor organic compounds such as lignin (Klap and others 2000), in turn increasing the accumulation of sedimentary Corg in seagrass meadows. Aboveground variables such as shoot biomass, canopy height, shoot density, and coverage had little or no influence on sedimentary Corg content and are clearly less important than is belowground seagrass biomass. This calls into question the importance of the aboveground structural complexity of seagrass habitats for carbon trapping and emphasizes the importance of the belowground component for seagrass meadow productivity. The great influence of the belowground compartment may explain some of the observed differences in sedimentary Corg content among different seagrass habitats (comparing the larger E. acoroides and T. ciliatum with the smaller T. hemprichii and Cymodocea spp.), as large seagrass species tend to develop higher belowground biomass than do seagrass species of smaller size (Duarte and Chiscano 1999).

Regarding the size of the accumulated sediment stock of Ccarb, we found that the particular seagrass species dominating the studied habitat played a negligible role. Thus, site-specific environmental conditions, landscape configuration, and/or latitude would be more important factors explaining variability in sedimentary Ccarb. In our study, the Zanzibar sites had substantially higher Ccarb contents than did both mainland Tanzanian sites (at the same latitude) and the sites on Inhaca Island in Mozambique. Sediments in Chwaka Bay and Pongwe, on the east coast of Zanzibar, have previously been demonstrated to comprise almost 100% biogenic calcium carbonate, whereas the sediment on the west coast was found to be a mixture of calcium carbonate and siliciclastic components (Shaghude and Wannäs 2000). In Chwaka Bay, the sediment is entirely biogenic with at least 50% of the Ccarb coming from calcareous Halimeda algae (Muzuka and others 2001, Shaghude and Wannäs 2000). Halimeda contributes greatly to calcium carbonate production in tropical and subtropical coastal areas (Rees and others 2007), including seagrass meadows of Chwaka Bay (Gullström and others 2006; Kangwe and others 2012), which could explain their high sedimentary Ccarb contents. In contrast to Zanzibar, the low Ccarb contents in seagrass sediment at the two Inhaca sites correspond to earlier findings that calcareous epiphytic algae and carbonate-producing Halimeda are of minor importance as contributors to sedimentary particulate inorganic carbon in these seagrass systems (Perry 2003; Perry and Beavington-Penney 2005).

There was generally a higher amount of CaCO3 in the sediment of seagrass habitats than in adjacent unvegetated areas and a clear relationship between the accumulation of Corg and of Ccarb, with Corg:Ccarb ratios of 0.1–0.3 in seagrass habitats and 0.06 in unvegetated areas (that is lower than the global mean of 0.74, but comparable to the global median of 0.2; Mazarrasa and others 2015). The amount of CaCO3 attributed to seagrass meadows has great implications for their carbon sink function. The process of calcification is a source of CO2, since during CaCO3 precipitation seawater pH will decrease until CO2 is eventually released to the atmosphere. At the same time as seagrass primary productivity fixes carbon as organic matter, pH increases, often substantially, in the surrounding seawater (for example, Frankignoulle and Distèche 1984; Frankignoulle and Bouquegneau 1990; Buapet and others 2013; Hendriks and others 2014), thereby enhancing the rate of calcification (for example, Frankignoulle and Gattuso 1993; Semesi and others 2009). Seagrass meadows can therefore, like coral reefs (Smith and Gattuso 2009), simultaneously release and store CO2, and high production of carbonate could convert a seagrass meadow from a sink to a source. Considering the general relationship between fixed and released CO2 in calcification (where 1 mol of carbonate formed results in the release in ~0.6 mol of CO2 to the atmosphere; Ware and others 1992), it follows that 1.67 mol of carbon fixed in carbonate will counteract the sink effect of 1 mol of carbon fixed as Corg. The sediment we studied contained 1.8–15.9 times more Ccarb than Corg (that is, within the reported global range of seagrass sediment stocks; Mazarrasa and others 2015), which in theory could mean that all our seagrass meadows are carbon sources if the net accumulation of CaCO3 in the sediment can be considered to be produced by the seagrass plant system. However, calcium carbonate production by seagrass systems is promoted in various ways. A substantial part of the CaCO3 in sediments has, for example, been reported to be produced directly within the leaves of Thalassia testudinum (Enríquez and Schubert 2014), and although this has not been reported for the species growing in our study area, it strongly suggests seagrass plant involvement in calcification. Seagrasses also promote calcification in other organisms (for example, calcareous algae or corals) by changing the carbon chemistry of the surrounding seawater, which has been demonstrated in, for example, Mediterranean Posidonia meadows (for example, Frankignoulle and Disteche 1984) and Indo-Pacific seagrass meadows, where the calcification could potentially be increased by 18% in nearby coral reefs (Unsworth and others 2012). In Chwaka Bay, seagrasses have been estimated to increase the calcification rate of various calcareous algae species by up to about six times (Semesi and others 2009). Seagrasses also constitute a substrate for calcareous epiphytic algae, which can be major contributors to the Ccarb level in seagrass sediment (Walker and Woelkerling 1988). Finally, by providing habitat for a wide range of organisms, seagrass meadows facilitate calcium carbonate production by harbouring high abundances of calcareous animals such as molluscs, echinoderms, and foraminifera (Orth and others 1984; Prager and Halley 1999; Debenay and others 1999).

Given that calcareous algae contribute substantially to the Ccarb content of seagrass meadows at some of our tropical study sites and that seagrass photosynthesis promotes their calcification rates, it is reasonable to assume that part of the carbonate produced by calcareous algae should be included when estimating these sites’ carbon sink–source balance. In addition, tropical and subtropical nearshore ecosystems are generally oversaturated in CO2 and considered net sources to the atmosphere (Borges and others 2005; Chen and Borges 2009). It is therefore probable that the carbon sink function of Chwaka Bay and Pongwe is counteracted by the CO2 released during the high production of carbonate. Generally, this would mean that highly productive tropical seagrass meadows with high carbonate production rates may not be as efficient carbon sinks as are seagrass habitats with proportionally lower carbonate contents.

Apart from plant–sediment- and plant–plant-related processes occurring within the seagrass habitat, the surrounding environmental conditions and landscape configuration may also influence the accumulation of carbon in the sediment. Spatial heterogeneity is a fundamental focus in ecology (Pickett and Cadenasso 1995) and is potentially very important for the variability of the carbon storage capacity in the coastal environment, where strong cross-habitat exchanges of carbon may occur (Bouillon and Connolly 2009; Hyndes and others 2014). Tropical seagrass ecosystems are part of a highly productive shallow-water environment and can receive large inputs from various terrestrial carbon sources (often through river input) as well as from adjacent similarly productive ecosystems such as mangroves (Bouillon and Connolly 2009). The amount of allochthonous carbon trapped within seagrass sediments has been estimated to account for 50–72% of the Corg pool of the surface sediment (Gacia and others 2002; Kennedy and others 2010). This could partly explain why different landscape configuration predictors (that is, area-based variables) were significantly related to the carbon (both Corg and Ccarb) content in the seagrass sediment. The proportions of different habitats in the area surrounding each survey location varied considerably, so we assume that the nature and strength of the carbon exchange might vary with the coastal landscape configuration and composition. We found a clear habitat-area effect at the landscape (km) scale on both Corg and Ccarb sedimentary pools, with negative relationships between mangrove and carbon content as well as between unvegetated area and carbon content. We interpret this as suggesting that when an area comprises large, continuous seagrass meadows, it will contain more carbon (Corg and Ccarb) in the sediment per area (Figrure 6). In the case of organic carbon, this is strengthened by the fact that the area of seagrass cover in the model was positively correlated with the sedimentary Corg level. The ongoing loss and fragmentation of seagrass areas worldwide (Waycott and others 2009) will affect the natural accumulation process of carbon. For instance, if a seagrass landscape is patchy (that is, highly fragmented or consisting of small meadow units), an increased area of edge effects might induce a reduced amount of accumulated Corg in the sediment (Ricart and others 2015, 2017; Oreska and others 2017). In contrast, landscapes with a high total area of seagrass cover were found to store more Corg in the sediment. Such effects of landscape structure on coastal sedimentary Corg and Ccarb stocks might in turn depend on multiple processes (for example, prevailing hydrodynamic conditions) that intricately affect the movement and exchange of carbon (Bouillon and Connolly 2009; Hyndes and others 2014; Watanabe and Kuwae 2015; Samper-Villarreal and others 2016). To understand the drivers of tropical coasts as intrinsically valuable carbon sinks, and thus to preserve them, it is critical to extend studies to a larger range of spatial (and temporal) scales and to further study and assess the underlying mechanisms of how cross-habitat carbon exchange varies in a landscape context.

Semi-conceptual illustration showing two coastal seascapes with clearly different landscape configuration, where the homogenous seascape (to the right) contains a higher organic carbon (Corg) stock per area in the seagrass sediment than the heterogeneous seascape (to the left). This indicates that high Corg stocks per area in seagrass meadows are related to seascapes with low proportions of mangrove and unvegetated habitats and large seagrass meadow area. This relationship was slightly weaker for Ccarb stocks as seagrass meadow area was of less importance as predictor compared to Corg. The results presented in this illustration are based on performance of the PLS modelling (see Figure 5).

References

Agawin NSR, Duarte CM. 2002. Evidence of direct particle trapping by a tropical seagrass meadow. Estuaries 25:1205–9.

Alongi DM. 2012. Carbon sequestration in mangrove forests. Carbon Manag 3:313–22.

Alongi DM, Murdiyarso D, Fourqurean JW, Kauffman JB, Hutahaean A, Crooks S, Lovelock CE, Howard J, Herr D, Fortes M. 2015. Indonesia’s blue carbon: a globally significant and vulnerable sink for seagrass and mangrove carbon. Wetl Ecol Manag 24:1–11.

Armitage AR, Fourqurean JW. 2016. Carbon storage in seagrass soils: long-term nutrient history exceeds the effects of near-term nutrient enrichment. Biogeosciences 13:313–21.

Avnimelech Y, Ritvo G, Meijer LE, Kochba M. 2001. Water content, organic carbon and dry bulk density in flooded sediments. Aquac Eng 25:25–33.

Barko J, Smart R. 1983. Effects of organic matter additions to sediment on the growth of aquatic plants. J Ecol 71:161–75.

Borges AV, Delille B, Frankignoulle M. 2005. Budgeting sinks and sources of CO2 in the coastal ocean: diversity of ecosystems counts. Geophy Res Lett 32:L14601.

Bouillon S, Connolly RM. 2009. Carbon exchange among tropical coastal ecosystems. In: Nagelkerken I, Ed. Ecological connectivity among tropical coastal ecosystems. Berlin: Springer. p 45–70.

Buapet P, Rasmusson LM, Gullström M, Björk M. 2013. Photorespiration and carbon limitation determine productivity in temperate seagrasses. PLoS ONE 8:e83804.

Canfield DE. 1994. Factors influencing organic carbon preservation in marine sediments. Chem Geol 114:315–29.

Canfield DE, Jørgensen BB, Fossing H, Glud R, Gundersen J, Ramsing NB, Thamdrup B, Hansen JW, Nielsen LP, Hall POJ. 1993. Pathways of organic carbon oxidation in three continental margin sediments. Mar Geol 113:27–40.

Carrascal LM, Galván I, Gordo O. 2009. Partial least squares regression as an alternative to current regression methods used in ecology. Oikos 118:681–90.

Cebrian J. 1999. Patterns in the fate of production in plant communities. Am Nat 154:449–68.

Chen C-TA, Borges AV. 2009. Reconciling opposing views on carbon cycling in the coastal ocean: continental shelves as sinks and near-shore ecosystems as sources of atmospheric CO2. Deep Sea Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr 56:578–90.

Dahl M, Deyanova D, Gütschow S, Asplund ME, Lyimo LD, Karamfilov V, Santos R, Björk M, Gullström M. 2016a. Sediment properties as important predictors of carbon storage in Zostera marina meadows: a comparison of four European areas. PLoS ONE 11:e0167493.

Dahl M, Deyanova D, Lyimo LD, Näslund J, Samuelsson GS, Mtolera MSP, Björk M, Gullström M. 2016b. Effects of shading and simulated grazing on carbon sequestration in a tropical seagrass meadow. J Ecol 104:654–64.

Davy AJ, Bakker JP, Figueroa ME. 2009. Human modification of European salt marshes. In: Silliman BR, Grosholz E, Bertness MD, Eds. Human impacts on salt marshes: a global perspective. Berkeley: University of California Press. p 311–35.

Debenay J-P, André J-P, Lesourd M. 1999. Production of lime mud by breakdown of foraminiferal tests. Mar Geol 157:159–70.

Duarte CM, Cebrián J. 1996. The fate of marine autotrophic production. Limnol Oceanogr 41:1758–66.

Duarte CM, Chiscano CL. 1999. Seagrass biomass and production: a reassessment. Aquat Bot 65:159–74.

Duarte CM, Kennedy H, Marbà N, Hendriks I. 2011. Assessing the capacity of seagrass meadows for carbon burial: current limitations and future strategies. Ocean Coast Manag 83:32–8.

Duarte CM, Losada IJ, Hendriks IE, Mazarrasa I, Marbà N. 2013. The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Nat Publ Gr 3:961–8.

Duarte CM, Marbà N, Gacia E, Fourqurean JW, Beggins J, Barrón C, Apostolaki ET. 2010. Seagrass community metabolism: assessing the carbon sink capacity of seagrass meadows. Global Biogeochem Cycles 24:GB4032.

Duarte CM, Merino M, Agawin NSR, Uri J, Fortes MD, Gallegos ME, Marbá N, Hemminga MA. 1998. Root production and belowground seagrass biomass. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 171:97–108.

Duarte CM, Middelburg JJ, Caraco N. 2005. Major role of marine vegetation on the oceanic carbon cycle. Biogeosciences 1:1–8.

Duarte MC, Bandeira S, Romeiras MM. 2012. Systematics and ecology of a new species of seagrass (Thalassodendron, Cymodoceaceae) from southeast African coasts. Novon a J Bot Nomencl 22:16–24.

Efron B, Gong G. 1983. A leisurely look at the bootstrap, the jackknife, and cross-validation. Am Stat 37:36–48.

Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. 1994. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman and Hall. p 456.

Enríquez S, Schubert N. 2014. Direct contribution of the seagrass Thalassia testudinum to lime mud production. Nat Commun 5:3835.

Fourqurean JW, Duarte CM, Kennedy H, Marbà N, Holmer M, Mateo MA, Apostolaki ET, Kendrick GA, Krause-Jensen D, McGlathery KJ, Serrano O. 2012. Seagrass ecosystems as a globally significant carbon stock. Nat Geosci 5:505–9.

Frankignoulle M, Bouquegneau JM. 1990. Daily and yearly variations of total inorganic carbon in a productive coastal area. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 30:79–89.

Frankignoulle M, Distèche A. 1984. CO2 chemistry in the water column above a Posidonia seagrass bed and related air-sea exchanges. Oceanol acta 7:209–19.

Frankignoulle M, Gattuso J-P. 1993. Air-sea CO2 exchange in coastal ecosystems. In: Wollast R, Mackenzie FT, Chau L, Eds. Interactions of C, N, P and S biogeochemical cycles and global change. Berlin: Springer. p 233–48.

Gacia E, Duarte CM, Middelburg JJ. 2002. Carbon and nutrient deposition in a Mediterranean seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) meadow. Limnol Oceanogr 47:23–32.

Glew JR, Smol JP, Last WM. 2001. Sediment core collection and extrusion. In: Last WM, Smol JP, Eds. Tracking environmental change using lake sediments, Vol. 1. New York: Springer. p 73–105.

Gullström M, de la Torre Castro M, Bandeira SO, Björk M, Dahlberg M, Kautsky N, Rönnbäck P, Öhman MC. 2002. Seagrass ecosystems in the western Indian Ocean. Ambio 31:588–96.

Gullström M, Lundén B, Bodin M, Kangwe J, Öhman MC, Mtolera MSP, Björk M. 2006. Assessment of changes in the seagrass-dominated submerged vegetation of tropical Chwaka Bay (Zanzibar) using satellite remote sensing. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 67:399–408.

Hendriks IE, Olsen YS, Ramajo L, Basso L, Steckbauer A, Moore TS, Howard J, Duarte CM. 2014. Photosynthetic activity buffers ocean acidification in seagrass meadows. Biogeosciences 11:333–46.

Hendriks IE, Sintes T, Bouma TJ, Duarte CM. 2008. Experimental assessment and modeling evaluation of the effects of the seagrass Posidonia oceanica on flow and particle trapping. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 356:163–73.

Hyndes GA, Nagelkerken I, McLeod RJ, Connolly RM, Lavery PS, Vanderklift MA. 2014. Mechanisms and ecological role of carbon transfer within coastal seascapes. Biol Rev 89:232–54.

Kangwe J, Semesi IS, Beer S, Mtolera M, Björk M. 2012. Carbonate Production by Calcareous Algae in a seagrass-dominated system: the example of Chwaka Bay. In: de la Torre-Castro M, Lyimo TJ, Eds. People, nature and research: past, present and future of Chwaka Bay, Zanzibar. Zanzibar Town: WIOMSA. p 143–56.

Kennedy H, Beggins J, Duarte CM, Fourqurean JW, Holmer M, Marbà N, Middelburg JJ. 2010. Seagrass sediments as a global carbon sink: isotopic constraints. Global Biogeochem Cycles 24:GB4026.

Kennedy H, Björk M. 2009. Seagrass meadows. In: Laffoley D, Grimsditch G, Eds. The management of natural coastal carbon sinks. Gland: IUCN. p 23–9.

Klap VA, Hemminga MA, Boon JJ. 2000. Retention of lignin in seagrasses: angiosperms that returned to the sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 194:1–11.

Knudby A, Nordlund LM, Palmqvist G, Wikström K, Koliji A, Lindborg R, Gullström M. 2014. Using multiple Landsat scenes in an ensemble classifier reduces classification error in a stable nearshore environment. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf 28:90–101.

Laffoley D, Grimsditch GD. 2009. The management of natural coastal carbon sinks. Gland: IUCN. p 53.

Lavery PS, Mateo M-Á, Serrano O, Rozaimi M. 2013. Variability in the carbon storage of seagrass habitats and its implications for global estimates of blue carbon ecosystem service. PLoS ONE 8:e73748.

Macreadie PI, Baird ME, Trevathan-Tackett SM, Larkum AWD, Ralph PJ. 2013. Quantifying and modelling the carbon sequestration capacity of seagrass meadows—a critical assessment. Mar Pollut Bull 83:430–9.

Macreadie PI, Trevathan-tackett SM, Skilbeck CG, Sanderman J, Curlevski N, Jacobsen G, Seymour JR. 2015. Losses and recovery of organic carbon from a seagrass ecosystem following disturbance. Proc R Soc B 282:20151537.

Mateo MA, Cebrián J, Dunton K, Mutchler T. 2006. Carbon flux in seagrass ecosystems. In: Larkum AWD, Orth RJW, Duarte CM, Eds. Seagrasses: biology, ecology and conservation. Dordrecht: Springer. p 159–92.

Mateo MA, Romero J, Pérez M, Littler MM, Littler DS. 1997. Dynamics of millenary organic deposits resulting from the growth of the Mediterranean seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 44:103–10.

Mateo MA, Serrano O. 2012. The carbon sink associated to Posidonia oceanica. In: Pergent G, Bazairi H, Bianchi CN, Eds. Mediterranean seagrass meadows: resilience and contribution to climate change mitigation. Gland: IUCN. p 80.

Mazarrasa I, Marbà N, Lovelock CE, Serrano O, Lavery PS, Fourqurean JW, Kennedy H, Mateo MA, Krause-Jensen D, Steven ADL, Duarte CM. 2015. Seagrass meadows as a globally significant carbonate reservoir. Biogeosciences 12:4993–5003.

Mcleod E, Chmura GL, Bouillon S, Salm R, Björk M, Duarte CM, Lovelock CE, Schlesinger WH, Silliman BR. 2011. A blueprint for blue carbon: toward an improved understanding of the role of vegetated coastal habitats in sequestering CO2. Front Ecol Environ 9:552–60.

Miyajima T, Hori M, Hamaguchi M, Shimabukuro H, Adachi H, Yamano H, Nakaoka M. 2015. Geographic variability in organic carbon stock and accumulation rate in sediments of East and Southeast Asian seagrass meadows. Global Biogeochem Cycles 29:397–415.

Muzuka ANN, Kangwe JW, Nyandwi N, Wannäs KO, Mtolera MSP, Björk M. 2001. Preliminary results on the sediment sources, grain size distribution and percentage cover of sand-producing Halimeda species and associated flora in Chwaka Bay. In: Richmond MD, Francis J, Eds. Marine science development in Tanzania and Eastern Africa. Proceedings of the 20th anniversary conference on advances in marine science in Tanzania, Institute of Marine Science (IMS)/Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association (WIOMSA), Zanzibar, Tanzania. p 51–9.

Oreska MPJ, McGlathery KJ, Porter JH. 2017. Seagrass blue carbon spatial patterns at the meadow-scale. PLoS ONE 12:e0176630.

Orth RJ, Heck KL, van Montfrans J. 1984. Faunal communities in seagrass beds: a review of the influence of plant structure and prey characteristics on predator-prey relationships. Estuaries and Coasts 7:339–50.

Pendleton L, Donato DC, Murray BC, Crooks S, Jenkins WA, Sifleet S, Craft C, Fourqurean JW, Kauffman JB, Marbà N, Megonigal P, Pidgeon E, Herr D, Gordon D, Baldera A. 2012. Estimating global ‘blue carbon’ emissions from conversion and degradation of vegetated coastal ecosystems. PLoS One 7:e43542.

Perry CT. 2003. Coral reefs in a high-latitude, siliciclastic barrier island setting: reef framework and sediment production at Inhaca Island, southern Mozambique. Coral Reefs 22:485–97.

Perry CT, Beavington-Penney SJ. 2005. Epiphytic calcium carbonate production and facies development within sub-tropical seagrass beds, Inhaca Island, Mozambique. Sediment Geol 174:161–76.

Pickett STA, Cadenasso ML. 1995. Landscape ecology: spatial heterogeneity in ecological systems. Science 269:331.

Prager EJ, Halley RB. 1999. The influence of seagrass on shell layers and Florida Bay mudbanks. J Coast Res 15:1151–62.

Rees SA, Opdyke BN, Wilson PA, Henstock TJ. 2007. Significance of Halimeda bioherms to the global carbonate budget based on a geological sediment budget for the Northern Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Coral Reefs 26:177–88.

Ricart AM, Pérez M, Romero J. 2017. Landscape configuration modulates carbon storage in seagrass sediments. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 185:69–76.

Ricart AM, York PH, Rasheed MA, Pérez M, Romero J, Bryant CV, Macreadie PI. 2015. Variability of sedimentary organic carbon in patchy seagrass landscapes. Mar Pollut Bull 100:476–82.

Röhr ME, Boström C, Canal-Vergés P, Holmer M. 2016. Blue carbon stocks in Baltic Sea eelgrass (Zostera marina) meadows. Biogeosciences 13:6139–53.

Rozaimi M, Lavery PS, Serrano O, Kyrwood D. 2016. Long-term carbon storage and its recent loss in an estuarine Posidonia australis meadow (Albany, Western Australia). Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 171:58–65.

Sadd JL. 1984. Sediment transport and CaCO3 budget on a fringing reef, Cane Bay, St. Croix, US Virgin Islands. Bull Mar Sci 35:221–38.

Samper-Villarreal J, Lovelock CE, Saunders MI, Roelfsema C, Mumby PJ. 2016. Organic carbon in seagrass sediments is influenced by seagrass canopy complexity, turbidity, wave height, and water depth. Limnol Oceanogr 61:938–52.

Semesi IS, Beer S, Björk M. 2009. Seagrass photosynthesis controls rates of calcification and photosynthesis of calcareous macroalgae in a tropical seagrass meadow. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 382:41–7.

Serrano O, Lavery P, Masque P, Inostroza K, Bongiovanni J, Duarte C. 2016a. Seagrass sediments reveal the long-term deterioration of an estuarine ecosystem. Glob Change Biol 22:1523–31.

Serrano O, Lavery PS, Rozaimi M, Mateo MÁ. 2014. Influence of water depth on the carbon sequestration capacity of seagrasses. Global Biogeochem Cycles 28:950–61.

Serrano O, Mateo MA, Renom P, Julià R. 2012. Characterization of soils beneath a Posidonia oceanica meadow. Geoderma 185–186:26–36.

Serrano O, Ruhon R, Lavery PS, Kendrick GA, Hickey S, Masqué P, Arias-Ortiz A, Steven A, Duarte CM. 2016b. Impact of mooring activities on carbon stocks in seagrass meadows. Sci Rep 6:23193.

Shaghude YW, Wannäs KO. 2000. Mineralogical and biogenic composition of the Zanzibar Channel sediments, Tanzania. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 51:477–89.

Smith SV. 1981. Marine macrophytes as a global carbon sink. Science 211:838–40.

Smith SV, Gattuso J-P. 2009. Coral reefs. In: Laffoley D, Grimsditch G, Eds. The management of natural coastal carbon sinks. Gland: IUCN. p 39–45.

Spalding MD, Kainuma M, Collins L. 2010. World atlas of mangroves. London, United Kingdom: Earthscan. p 336.

Trevathan-Tackett SM, Kelleway J, Macreadie PI, Beardall J, Ralph P, Bellgrove A. 2015. Comparison of marine macrophytes for their contributions to blue carbon sequestration. Ecology 96:3043–57.

Unsworth RKF, Collier CJ, Henderson GM, McKenzie LJ. 2012. Tropical seagrass meadows modify seawater carbon chemistry: implications for coral reefs impacted by ocean acidification. Environ Res Lett 7:24026.

Walker DI, Woelkerling WJ. 1988. Quantitative study of sediment contribution by epiphytic coralline red algae in seagrass meadows in Shark Bay, Western Australia. Mar Ecol Prog Ser Oldend 43:71–7.

Ware JR, Smith SV, Reaka-Kudla ML. 1992. Coral reefs: sources or sinks of atmospheric CO2? Coral Reefs 11:127–30.

Watanabe K, Kuwae T. 2015. How organic carbon derived from multiple sources contributes to carbon sequestration processes in a shallow coastal system? Glob Change Biol 21:2612–23.

Waycott M, Duarte CM, Carruthers TJB, Orth RJ, Dennison WC, Olyarnik S, Calladine A, Fourqurean JW, Heck KL, Hughes AR, Kendrick GA, Kenworthy WJ, Short FT, Williams SL. 2009. Accelerating loss of seagrasses across the globe threatens coastal ecosystems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:12377–81.

Wold S, Sjöström M, Eriksson L. 2001. PLS-regression: a basic tool of chemometrics. Chemom Intell Lab Syst 58:109–30.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Damboia Cossa, Marcia Nrepo, and Alima Taju for help with the fieldwork in Mozambique. We also thank Mathew Silas, Said Mgeleka, Gustav Palmqvist, Karolina Wikström, Alan Koliji, Regina Lindborg, Linus Hammar, Linda Eggertsen, Sandra Andersson, and Johan Haglund for help with the groundtruthing of habitat maps. Furthermore, we thank the staff at the Institute of Marine Sciences in Zanzibar and at the Estação de Biologia Marítima on Inhaca Island for facilitating laboratory work. The research was funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) through the Bilateral Marine Science Programme between Sweden and Tanzania and through a 3-year research project grant (SWE-2010-194).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author contributions

MG, MB, and HWL conceived and designed the study. MG, LDL, GSS, ME, EA, LMR, SB, and LMN performed field research and laboratory analyses. MG, LDL, MD, GSS, AK, and MB analysed data. MG led the writing of the paper with substantial input from MB, MD, and LDL; other authors commented on and edited the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gullström, M., Lyimo, L.D., Dahl, M. et al. Blue Carbon Storage in Tropical Seagrass Meadows Relates to Carbonate Stock Dynamics, Plant–Sediment Processes, and Landscape Context: Insights from the Western Indian Ocean. Ecosystems 21, 551–566 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-017-0170-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-017-0170-8