Abstract

A small group of youth and emerging adults deals with severe and enduring mental health problems (SEMHP). Current mental health care struggles to recognize and treat this group timely and adequately, leaving these youth between the cracks of the system. A first step to improve care for this group is to gain a deeper understanding of the characteristics of youth with SEMHP. Therefore, this study aimed at reviewing current literature about this target group and what is known so far about their characteristics. We included 39 studies with a focus on youth aged 12–25 years with SEMHP. After critical appraisal, a content analysis and in-depth thematic analysis were conducted. According to the included studies, youth with SEMHP were characterized by severe distress and recurrent comorbid mental health problems, with pervasive suicidality. Further, underlying trauma, family conflicts, peer rejection, deep feelings of hopelessness, and psychosocial malfunctioning characterized SEMHP. It was described that for youth with SEMHP a pervasive pattern of dysfunction in multiple domains is present leading to a detrimental impact. Subsequently, this pattern exerts a reciprocal influence on the mental health problems, causing a vicious circle further worsening SEMHP. Our findings emphasize the need for a holistic approach and to look beyond the traditional classification system in order to meet the needs of these youth with wide-ranging comorbid mental health problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Attention is urgently needed for youth and emerging adults (referred to as youth in this paper), who fall between the cracks of current mental health care. While for most youth in mental health services, mental health problems are treatable and transient, a small group of youth experiences severe and enduring mental health problems (SEMHP). Severe and enduring mental health problems include socio-emotional, behavioral, and academic difficulties, often resulting in severe self-harm or suicidal attempts [1, 2]. For youth with SEMHP, the current mental health care all too often seems unsuitable [3]. Current mental health care tends to focus on classifications: the assignment of a mental disorder to a set of criteria that interferes with daily functioning. However, youth with SEMHP are often assigned to multiple classifications without adequate attention to the underlying mental health problems. These classifications do not provide information about the causes and are therefore limited in guiding the diagnostic process [4]. At present, we lack the means to recognize SEMHP youth timely and correctly. Therefore, an approach beyond the classifications is needed. A first step to improve care for this group, is to gain a deeper understanding of the characteristics of youth with SEMHP.

Growing evidence, supporting the need for a different approach, shows the presence of an underlying dimension in adults with severe and enduring mental disorders: a common vulnerability for psychopathology, the P-factor [5, 6]. In a pediatric sample, similar results were found for the younger age group [2]. According to the P-factor theory, mental health disorders are interconnected and caused by transdiagnostic genetical and environmental factors [7]. The P-factor theory implies that individuals with a diversity of severe and enduring symptoms, are likely to share the same underlying vulnerability. Various circumstances—for instance, (sexual) abuse, personal loss, poverty or being bullied- may trigger the development of (severe and enduring) mental health problems, subsequently resulting in a diversity of classifications. The current focus in mental health care on specific classifications [8], lacks focus on underlying psychopathology, personal characteristics and factors that trigger a set of symptoms [5]. Moreover, although clinical practice does describe youths’ problems as severe and enduring, it remains unclear how we define or evaluate this severity [9]. To better understand youth with SEMHP, it is needed to look beyond standard symptoms and further discover explanatory factors and characteristics related to severe and enduring.

For adults with severe and enduring problems, Delespaul et al. formulated a description that enables to recognize them, based on clear inclusion and exclusion criteria [10]. This description includes: (a) a psychiatric disorder requiring care; (b) with severe disabilities in social functioning (which may fluctuate); (c) where the disability is both cause and effect; (d) which is not transient; and (e) where coordinated care from professionals is required [10]. Although helpful, these criteria are at best only partly applicable for youth, as it is difficult to establish whether youth’ mental health problems are temporary or may vanish due to their maturation [11]. In order to formulate a description of SEMHP that fits youth, further research on their characteristics is crucial.

The aim of this study was to explore the characteristics of youth with SEMHP from current literature. Since little research has been done on this specific group, we choose to conduct a descriptive systematic review. Based on a content and thematic analysis, an overview of characteristics will be provided on three levels: (a) current descriptions of severe mental health problems and enduring mental health problems; (b) contributing factors to the development and continuation of SEMHP; c) the impact of SEMHP.

Methods

This systematic review was performed following the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). A research protocol was prospectively registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (Prospero) in 2021 (CRD42021239131). To identify and describe themes in this systematic review, we conducted a content- and thematic analysis, consisting of the following five steps: framing questions, identifying relevant work, assessing the quality of studies, summarizing the evidence, and interpreting the findings [12].

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a research librarian from the Leiden University Medical Center. Four databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library) were searched using the search terms presented in Appendix A. Search terms were related to the following concepts of interest: (a) youth, such as children, pediatrics, teenagers, adolescents and youth; (b) mental health problems, mental disorders, psychiatric disorders; (c) severe and enduring including their synonyms; (d) biopsychosocial factors; (e) impact. Keywords were generated for each of these concepts by examining terminology used in recent review papers in mental health problems literature [13, 14]. These key words were combined with MeSH terms from the PubMed and Cochrane databases and Subject Headings for the PsychINFO database. In addition, we performed a search by hand: checking the reference lists of the included studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included, studies had to meet the following eligibility criteria:

-

Studies focused on youth and emerging adults (youth) aged 12–25 years. Studies with a broader age range were included as long as the mean age of the participants fell between 12 and 25 years.

-

Studies focused on the characteristics of youth with severe and enduring mental health problems (SEMHP). A “characteristic” was defined as a feature belonging typically to a person or their environment serving to identify them. The definition of severe and enduring in terms of mental health problems was based on a definition of severe psychiatric problems for adults established by Delespaul [10], serving as a starting point. Thus, severe mental health problems were defined as: (a) serious/severe interrelated mental health problems that; (b) necessitate care; (c) with severe disabilities in social functioning. And enduring mental health problems were defined as (a) not transient/structural/persistent; or (b) recurring.

-

Studies were peer-reviewed, including qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method studies.

-

Studies were published between 1992 and 2023 [15], in a peer-reviewed, English-language journal. Full-text had to be available.

Studies were excluded according to the following criteria:

-

Studies were not peer-reviewed, including but not limited to: editorials and letters, graduate-level thesis, conference abstracts and notes.

-

Studies focused on physical diseases (medical conditions) or medical treatment.

-

Studies focused on youth with a specific single mental health problem or mental disorder (e.g. solely a gaming disorder).

-

Studies focused on treatment without any description of the target group.

-

Studies focused on specific non-western population (e.g. native Indians).

Study selection

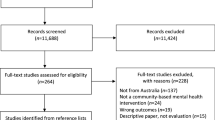

The initial database search returned 2034 published abstracts after removing duplicates. At the first stage, the main author (CB) screened the titles and excluded all studies concerning straightforward specific medical conditions. In the second stage, two researches (CB & RS) independently screened titles and abstracts and excluded studies based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were discussed in order to reach consensus. If consensus could not be reached, a third researcher (HE) was consulted. An overview of the study selection process is presented in Fig. 1: PRISMA Flowchart [16].

Data extraction and analysis approach

An extraction form, based on the Cochrane Data Extraction Template [17], was applied in the data extraction process. This form included study characteristics (i.e. research questions, study methodology, setting), source of evidence from eligible studies, and a description of the target population (i.e. type of mental health problems). In order to avoid publication bias, all studies were checked for using the same dataset. This was the case for eight studies, which were counted as one in the evaluation of evidence.

Subsequently, a combined thematic and content analysis was performed. The content analysis was conducted in order to quantify and examine the presence and meaning of themes [18]. In addition, the thematic analysis was conducted for identifying, examining and reporting themes within the data [19]. For both the thematic and content analysis, the same set of analytical interventions were operated as follows: preparation of the data (familiarizing), organizing the data (open coding, grouping codes), and synthesizing themes and reporting the results in categories [20]. The coding process was supervised by a second reviewer, experienced in qualitative literature reviews (LAN). For the thematic and content analysis, the results section of the included studies were coded. To code the data, a software program (Atlas.ti.9) was used. First, open coding was conducted in order to identify relevant text units. Also, selective coding was performed based on the biopsychosocial model [21]. Then, axial coding took place by grouping together similar codes using descriptive themes. We pre-defined the themes: Biological factors, Psychological factors and Sociological factors, based on the biopsychical model [21]. Also, we pre-defined the theme Descriptions and subthemes Severe and Enduring to gain more insight into the meaning of these terms. Then, to answer the research questions, all themes and subthemes were divided into the folowingthree pre-defined categories (a) the meaning of severe and enduring mental health problems (severe and enduring); (b) contributing factors to the development and continuation of SEMHP (contributing factors); and (c) the impact of youth experiencing SEMHP (impact). In order to prevent interpretation bias, a second reviewer (LAN) evaluated the identified themes on relevance and potential overlap.

Quality assessment

The quality of the individual studies (case reports, case series, cross-sectional studies, qualitative studies, reviews, and cohort studies) was appraised using standardized checklists of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [22]. The Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) was applied on randomized controlled trials [23], and case control studies [24]. The researchers used a predeveloped ranking system [25] in order to assess the study quality based on the checklist. The quality ranking system included the following three categories: high (more than 8 items checked), medium (6–8 items checked), and low (less than 6 items checked). An overview of the study characteristics and critical appraisal scores can be found in Appendix B.

Strength of evidence

The strength of evidence of each subtheme was calculated [26], based on the following predefined criteria [25]:

-

Size of evidence: the size of evidence was calculated using the number of studies within a subtheme. Subthemes consisting of 15 or more studies were graded as large (+); between 5 and 15 studies as medium (±); and less than 5 studies as small (−).

-

Quality of studies: based on the critical appraisal checklists for individual studies the overall quality of the subtheme was assessed. High (+); was awarded to subthemes consisting of > 75% of studies appraised as high quality. Medium (±); was awarded to subthemes consisting of 25–75% of high quality studies. Low (−); was awarded to subthemes consisting of > 25% high quality studies.

-

Context: the context of each subtheme was categorized into mixed or specific. Mixed (+) was assigned to subthemes consisting of studies including multiple contexts: comorbid psychiatric classifications with multiple mental health problems. Specific (−) was assigned to subthemes consisting of studies focusing on a specific context: a psychiatric classification with multiple mental health problems (e.g. eating disorder with suicidality).

-

Consistency: subthemes including evidence pointing to similar conclusions were considered consistent (+); subthemes including studies on different subpopulations (youth with different psychiatric classifications, e.g. MDD with PTSD versus ED with suicidality), with inconsistent results were considered mixed (i.e. not consistent and not inconsistent, ±); and subthemes including studies directly countering findings based on the same subpopulation were considered inconsistent (−).

-

Perspective (source of evidence): subthemes in which the source of evidence came from two or more perspectives (participants): youth, parents, professionals (e.g. practitioners) were considered mixed (+); and subthemes in which the source of evidence came from one perspective were considered single (−).

-

Area of life: Subthemes with findings from different settings (e.g. in-patient and out-patient) were considered mixed (+); and subthemes with findings from one setting (e.g. household) were considered specific (−).

Based on the scores assigned in each subscale (i.e. size of evidence, quality of studies, context, consistency, perspective and area of life), the overall strength of evidence was calculated: very strong (++++), strong (+++), medium (++), limited (+), or no evidence (−).

Results

Study characteristics

This systematic review included 39 studies. Most studies were cross-sectional or cohort studies. Critical appraisal of individual studies resulted in 19 high quality studies, 18 medium quality studies, and two low quality studies. The included studies covered a variety of target group descriptions and classifications. An overview of all study characteristics can be found in Appendix B.

Outcomes

The thematic analysis included three overarching categories, seven main themesand 20 subthemes (see Table 1 for an overview of categories, themes, and subthemes). The strength of evidence was evaluated for each subtheme based on the predeveloped rating scheme, with most subthemes being strong (n = 14) or medium (n = 9), and only one subtheme with limited to no evidence. A detailed description of the strength of evidence per subtheme can be found in Appendix C.

Category 1. Severe and enduring

This category includes subthemes focused on the descriptions of severe and enduring in terms of mental health problems. In addition to the descriptions of severe mental health problems, a separate main theme focusses on clinical associations including suicidality and comorbidity, which were frequently described in relation to severe and enduring.

Main theme: Descriptions of severe and enduring mental health problems in youth

Descriptions of severe mental health problems

Descriptions of severe in terms of mental health problems [27,28,29,30,31] were related to: (a) ‘a lot’ or ‘extreme’ impairment in daily activities, with serious consequences on the ability to return home, to finish school and to develop personal autonomy to pursue life goals [28,29,30], in combination with (b) severe/ very severe distress [27, 29, 31]. Moreover, some studies mentioned (c) shortened life expectancy [28]; and (d) symptom recognition by both parents and adolescents [29].

Descriptions of enduring mental health problems

Descriptions of enduring in terms of mental health problems included: (a) persistent or recurrent [32, 33]; (b) early onset of mental health problems [27, 32]; (c) duration of illness [29, 34, 35]; (d) duration of treatment: > 6 months [29, 32]. In three studies, mental health problems were reported as enduring after a duration of 12 months [29, 34, 35]. However, in two out of these three studies no association was found between experiencing SEMHP and the duration [34, 35].

Main theme: clinical associations with the descriptions of severe and enduring mental health problems

Since suicidality and comorbidity were often described in relation to severe and enduring, we devoted separate themes to these clinical associations. Studies in the subtheme suicidality [29, 30, 34, 36,37,38,39] all reported an association between SEMHP and increased suicidality. Studies in the subtheme comorbidity [30, 34, 40, 41] all described the presence of co-occurring psychiatric classifications as part of SEMHP.

Category 2. Contributing factors

Contributing factors are identified as risk factors for the development or the continuation of SEMHP. These contributing factors were categorized based on the biopsychosocial model [21], including biological factors (e.g. heredity), psychological factors (e.g. trauma), and sociological factors (e.g. socio-economic factors).

Main theme: biological factors

Heredity

The role of heredity was reported in seven studies [27, 29, 42,43,44,45,46]. In most studies familial psychiatric history was associated with substance abuse problems, major depression, and antisocial personality disorder as the highest risk [27, 29, 43,44,45]. Although this evidence seems clear, there were two studies [42, 46] that showed no evidence for any association between family history of substance abuse or major depression and youth experiencing SEMHP.

Age

The role of age was reported in nine studies [30, 32, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. However, evidence for the association between age and SEMHP in youth was mixed. First, the influence of age seems to be disorder-specific, for example an increased risk of substance use disorder as youth their age increases [30, 46, 48]. Second, youth were found to be the most vulnerable to co-occurring problems [47], such as suicidal behavior [51]. On the contrary, two studies reported increased mental health problems in younger children [32, 52]. Lastly, some studies reported no differences in age between youth with one specific psychiatric disorder and youth with comorbid psychiatric disorders [46, 49, 50].

Gender

The role of gender was reported in 16 studies [27, 30, 38, 39, 41, 43, 45, 46, 48, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. However, the evidence was mixed, and seemed related to the type of mental health problem (see Table 2). In seven studies, no association was found between gender and mental health problems in youth with SEMHP. More specifically, contradictory results were found for the relation between being female and suicidal behavior/experiencing mixed psychiatric disorders (see Table 2).

Main theme: psychological factors

Trauma

The role of trauma was reported in 12 studies as a contributing factor to SEMHP [27,28,29, 42,43,44,45, 47, 49, 50, 53, 57]. All studies confirmed a substantially elevated exposure to traumatic events for youth with SEMHP. Traumatic exposure for these youth consisted of (a) high rates of a history of abuse and/or neglect (sexual, physical, emotional) [27, 29, 42,43,44,45, 49, 57]; (b) more than twice as likely to report (domestic) violence than youth with a single classification or no classification [28, 44, 47, 49, 50]; and (c) death of a loved one [43, 44].

Main theme: sociological factors

Socio-economic factors

Socio-economic factors were mentioned in 21 studies [27, 28, 30, 32, 36,37,38, 42, 44, 46, 48, 50, 53, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. Distinctions between the different types of socioeconomic status in relation to SEMHP can be found in Table 3. Inconsistent results were found for low SES and low household income as a risk factor for the continuation of SEMHP. Furthermore, high SES and high household income were associated as protective factors in youth with SEMHP.

Family functioning

The role of family functioning was mentioned in 14 studies [28, 31, 35, 39, 43, 44, 46, 48, 51, 55,56,57, 60, 61]. Distinctions between the different types of risk factors in family functioning in relation to SEMHP can be found in Table 4. A single-parent home was reported as a risk factor associated with SEMHP, but only for youth with substance use disorder, conduct disorder and major depressive disorder [39, 56].

Peer support

A lack of peer support was mentioned in five studies [31, 39, 45, 53, 63]. Decreased social support in terms of peer-rejection was related to mental health problems in general [31, 39, 45, 63]. Also, one study reported higher quality of social interaction and support of peers in youth with non-specific mental health problems, compared to youth with internalizing and externalizing mental health problems [53].

Ethnical factors

Ethnicity was mentioned in six studies [27, 36, 45, 48, 58, 60]. Ethnicity seems to play an role in youth with SEMHP, however the relation remains unclear. This because the evidence was mixed, depending on the type of mental health problem. It was found that anxiety disorders were more prevalent among ethnic minorities [36, 60], while mood disorders were more prevalent among Caucasian youth with parents with higher levels of education [36, 60]. Also, an increased risk of treatment drop-out was found for youth with SEMHP of a foreign nationality [27]. Another study found that Hispanic youth often experience symptoms of a comorbid psychiatric disorder, both internalizing and externalizing [48]. However, two studies found no association between ethnicity and youth experiencing SEMHP [45, 58].

Category 3. Impact of youth experiencing severe and enduring mental health problems

This category ‘impact’ should be interpreted as the consequences of experiencing SEMHP for youth themselves, their environment and the society they are living in.

Main theme: Impact on youth

Academic functioning

All eight studies within this theme confirmed problems in academic functioning due to experiencing SEMHP [28,29,30, 34, 53,54,55, 60]. These youth experienced academic failure [34], impaired school work [30, 54], problems with school attendance [29, 53] and problems with finishing school [28].

Psychosocial functioning

All 11 studies [28,29,30, 34, 44, 49, 53,54,55, 57, 60] confirmed problems in psychosocial functioning associated with experiencing SEMHP. Psychosocial functioning included an adolescent’s ability to function socially and emotionally, in which SEMHP were causing e.g. poor quality of life, low self-esteem, and problems with autonomy, family and emotions. Experiencing these psychosocial impairment resulted in a considerable risk potential for an accumulation of complicating factors and future chronicity [30].

Hopelessness

Feelings of hopelessness in youth were mentioned in five studies [33, 36,37,38, 63]. These feelings of hopelessness were higher in youth with SEMHP [33, 36, 38], particularly in youth with severe dysregulated profiles and internalizing problems, in combination with suicidal behavior [33, 36]. Also, hopelessness was associated when youth with SEMHP experienced the following: a negative view of the self, negative view of the world, negative internal attribution, family problems, and/or low positive problem solving orientation [63]. However, there was one study that reported no association with hopelessness after controlling for depression [37].

Suicide attempts

Multiple suicide attempts due to experiencing SEMHP was mentioned in 15 studies [27, 29, 34, 36, 37, 39, 44, 45, 47, 50, 51, 54,55,56,57]. Suicide attempt as means to regulate intense emotions [37] was associated with SEMHP, especially when anxiety and depression were involved [29, 36, 50, 51, 54,55,56,57].

In one study, no differences in attempted suicide rates were found between youth with substance use disorder (SUD) and youth without SUD [57].

Substance abuse

Substance abuse in youth was mentioned in seven studies [27, 28, 36, 39, 49, 64, 65]. Five studies found prior mental health problems as a risk factor for comorbid substance use disorder in youth with SEMHP [28, 36, 49, 64, 65], and one study describes substance abuse as means of self-medication [27]. In reverse, one study claimed no unidirectional relation of substance abuse due to experiencing SEMHP, but rather a bi-directional relation, dependent on personal characteristics, the environment and circumstances [39].

Criminal behavior

Seven studies confirmed criminal behavior due to experiencing SEMHP [27, 38, 44, 47, 49, 53, 65]. More specifically, 25% of youth with SEMHP reported having been in contact with the legal system [53]. Subgroups most involved were youth with externalizing and overly impulsive problems [44, 53].

Main theme: The societal effects of youth with severe and enduring mental health problems

Costs

One study mentioned the societal impact of youth with SEMHP in terms of costs [28], namely that the indirect cost of mental health are high due to unemployment/absence from work/chronic sick leaves.

Policies

Two studies mentioned the societal impact of youth with SEMHP in terms of policies [28, 53]. These studies underline that treatment for youth with multiple and severe psychiatric disorders became even more complex and less accessible [28, 53]. The studies mentioned two policy issues in developed countries such as Portugal and the Netherlands: (a) there were disparities between political investments in mental health services compared with other areas of healthcare [28]; and (b) limited access to the required services [53].

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the characteristics of youth with severe and enduring mental health problems (SEMHP) in the existing literature. It appears that there is knowledge of contributing factors and the impact of various combinations of classifications on youth functioning in separate publications. However, it seems that no previous study combined these results before in order to describe a target group experiencing heterogenous and severe mental health problems. In this systematic review, we are one of the first to look beyond the classifications and focus on the underlying characteristics of youth with SEMHP.

Our results indicate that youth with SEMHP are characterized by co-occurring mental health problems, frequently in combination with pervasive suicidality. The severity of their mental health problems are interpreted by the experienced serious impairment in functioning in combination with severe distress. The endurance of their mental health problems is interpreted by the recurrent character often with an early onset. An important contributing factor associated with SEMHP was an underlying trauma, which seems to be a pervasive factor. Also, a low household income; problems in family functioning, such as separated parents and family conflict; and lack of support by family and peers were identified as contributing factors to SEMHP. As a result, youths’ development is hindered on multiple domains such as academic and psychosocial functioning with often reported substance abuse, criminal behavior and deep feelings of hopelessness.

Overall, several studies reviewed outline a pervasive pattern of dysfunction in multiple domains leading to a detrimental impact on youths’ daily life. Even more, classifications do not seem to describe the core of SEMHP. By solely focusing on the classifications, without attention for the underlying mental health problems, youth may feel unheard and unrecognized. The section below discusses the most relevant characteristics of youth with SEMHP per category in light of this review results, followed by a discussion of future directions and strengths and limitations.

Severe and enduring

In the current mental health system, the concept of severity in terms of mental health problems often refers to the intensity of symptoms using a ranking system [9, 66, 67]. However, in this study we suggest a different interpretation of severity, focusing on the level of impairment and distress experienced by youth with SEMHP. Similar to the results of Fonagy et al. [9], we identified clinical associations with SEMHP including a varying range of co-occurring mental health problems, often in combination with suicidality, but also with deep feelings of hopelessness. This implies that no specific DSM classification can be ascribed to the target group of youth with SEMHP, and that there is a need for a different description. Moreover, to gain a better understanding of youth with SEMHP, more research is needed into co-occurring mental health problems. In addition to the P-factor theory, currently different approaches [4, 68], such as Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) model [69] and the Research Domain Criteria (RDoc) system [68], focus on the underlying connections between conditions in a dimensional model [69], while similarly taking into account explanatory underlying transdiagnostic mechanisms [4, 68]. Future studies should explore to what extent these approaches fit the target group whose characteristics we have identified.

Contributing factors

Our results show a pervasive pattern of (childhood) trauma associated with youth with SEMHP. This finding is supported by various prior studies through the years, in combination with the effects of parental mental illness on youth [9, 70, 71]. Therefore, in order to provide adequate mental healthcare for youth with SEMHP, identifying and treating trauma in both youth and their parents is crucial. This requires sufficient time, skilled practitioners and resources. Moreover, attention should be paid to psychosocial environment (e.g. lack of support by family and peers) of youth with SEMHP. While for most youth puberty is a time of detachment from parents and greater reliance on peers [72], for youth without strong social connections, puberty is a high risk period which can be the beginning of severe and enduring mental health problems [9, 73, 74]. Although the underlying trauma and social connections seems crucial in youth with SEMHP, it is lacking in the current description of the SEMHP population [10]. In diagnosing youth with SEMHP, a holistic approach is needed including youths’ psychosocial support system so that factors such as trauma, peer rejection and/or family conflicts are identified faster and youth can be supported better.

Impact

Experiencing SEMHP has an enormous impact on youths’ feelings and behavior. Similar to the description of Delespaul [10] our results show severe disabilities in social functioning for youth with SEMHP, such as hindered academic and psychosocial functioning combined with poor quality of life, low self-esteem, suicidal behavior and deep feelings of hopelessness. The impact of SEMHP on youth seem to perpetuate the problem, where the disability is both cause and effect [10]. This vicious cycle is a considerable risk potential for an accumulation of complicating factors and future chronicity [30]. Therefore, practitioners should not only focus on the symptoms related to illness, but also (and maybe preferably) on the interaction of symptoms with functioning in different areas of life. This interaction may also differ between individuals, and that is why it is so important to start a conversation with youth themselves, instead of (only) targeted treatment based on a protocol.

Strengths and limitations

This review has several strengths. First, we reduced the risk of reporting bias by prospectively registering our review protocol in PROSPERO. Second, to increase applicability and generalizability a wide range of (a) mental health problems; (b) perspectives; (c) mental health care settings were included. Third, we reduced the selection bias by independent screening of the articles by two researchers. Fourth, in order to guarantee the quality, we critically appraised the individual studies and assessed the strength of evidence per subtheme. Only two articles that were included were of low quality and for only one subtheme the evidence appeared weak due to lack of studies.

Undeniably, our results should be interpreted in the context of various limitations. Our search terms were very broad without clear demarcation for the terms severe and enduring, making it difficult to measure whether studies were about the same group. We decided to refer to these youth as youth with severe and enduring mental health problems (SEMHP). In doing so, we did not apply any cut-off scores for severity in terms of grading scores, such as the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score [75]. We aimed to go beyond the traditional way of classifying symptoms based on a list of criteria and time restraints, as the DSM-5 does [4]. We also decided to explore the term enduring without any cut-off score for the duration of mental health problems. Hence, the lack of numeric scores to assess which study should be included, can be seen as a limitation of this review. However, we believe that our carefully chosen set of descriptive inclusion criteria fits the heterogeneous nature of the SEMHP population. Furthermore, our target group experiences heterogenous mental health problems resulting into inclusion of studies with various mental health problems with unquestionably different outcomes and expressions. However, because we have not limited ourselves to a specific mental health problem or one combination of comorbid mental health problems, we can learn more about any common denominator, and that is what makes this study so unique. Moreover, while the screening process and the thematic analysis were performed with multiple researchers, the coding process has been done by only one researcher. Despite supervision by a senior researcher, this is a limitation of this paper because it might add subjectivity to the results. In addition, we have made a distinction between factors that affect the development and continuation of SEMHP (contributing factors) and the consequences of experiencing SEMHP (impact). We have tended to describe directional relations, whereas there is no evidence for this. This review shows that there is no specific evidence for a causal relationship, however we do know that there is an interaction between these factors, consequences and SEMHP. That is the strength of this study, as well as the complexity. Moreover, with respect to ethnicity, our results should be interpreted with caution. None of our articles reported third-world countries which undoubtably also have youth with severe and enduring mental health problems [76]. However, for Western youth, interpretation of the data seems sufficient. Finally, since this review is not a meta-analysis, we were unable to draw conclusions about causal relationships, strength of the associations, or whether one factor is more important than another. Therefore, further research of the personal and environmental factors is needed to identify potential moderators.

Conclusion

This review is the first to thematically explore and describe characteristics of youth with severe and enduring mental health problems (SEMHP). While the traditional classification system has long been used to describe mental problems, this review suggests shifting the focus to a more descriptive diagnoses including personal and environmental factors. In particular, trauma and suicidality seem key elements in understanding youth with SEMHP and therefore should be included in diagnostic decision making. Also, the pervasive patterns of dysfunction in multiple domains leading to a crucial impact, such as hindered academic and psychosocial functioning, substance abuse and deep feelings of hopelessness should be taken into account by practice. In order to understand the vicious cycle of (mental health) problems experienced by youth with SEMHP, more research is needed into the comorbid mental health problems and what underlies them. This should be done in cooperation with these youth.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chadda RK (2018) Youth & mental health: challenges ahead. Indian J Med Res 148:359

Patalay P, Fonagy P, Deighton J, Belsky J, Vostanis P, Wolpert M (2015) A general psychopathology factor in early adolescence. Br J Psychiatry 207:15–22

Colizzi M, Lasalvia A, Ruggeri M (2020) Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health: is it time for a multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic model for care? Int J Ment Heal Syst 14:1–14

van der Heijden P, Hendriks M, Witteman C, Egger J (2020) Transdiagnostische modellen voor diagnostiek van psychische stoornissen: implicaties voor de opleiding van psychologen.

Lahey BB, Applegate B, Hakes JK, Zald DH, Hariri AR, Rathouz PJ (2012) Is there a general factor of prevalent psychopathology during adulthood? J Abnorm Psychol 121:971

Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Goldman-Mellor SJ, Harrington H, Israel S, Meier MH, Ramrakha S, Shalev I, Poulton R (2014) The p factor: one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clin Psychol Sci 2:119–137

Caspi A, Moffitt TE (2018) All for one and one for all: mental disorders in one dimension. Am J Psychiatry 175:831–844

American Psychiatric Association A, Association AP (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Fonagy P, Campbell C, Constantinou M, Higgitt A, Allison E, Luyten P (2021) Culture and psychopathology: an attempt at reconsidering the role of social learning. Dev Psychopathol 34:1–16

Delespaul P (2013) Consensus regarding the definition of persons with severe mental illness and the number of such persons in the Netherlands. Tijdschr Psychiatr 55:427–438

Patalay P, Gage SH (2019) Changes in millennial adolescent mental health and health-related behaviours over 10 years: a population cohort comparison study. Int J Epidemiol 48:1650–1664

Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G (2003) Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med 96:118–121

van der Put CE, Assink M, Gubbels J (2020) Differences in risk factors for violent, nonviolent, and sexual offending. J Foren Psychol Res Pract 20:341–361

Witt K, Milner A, Spittal MJ, Hetrick S, Robinson J, Pirkis J, Carter G (2019) Population attributable risk of factors associated with the repetition of self-harm behaviour in young people presenting to clinical services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 28:5–18

Goldberg DP, Huxley P (1992) Common mental disorders: a bio-social model. Tavistock/Routledge

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 10:1–11

Harris J (2011) Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions

Morgan DL (1993) Qualitative content analysis: a guide to paths not taken. Qual Health Res 3:112–121

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101

Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T (2013) Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 15:398–405

Engel GL (1977) The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 196:129–136

Joanna Briggs Institute (2020) The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews, Checklist. [online]

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2022) CASP (Randomised Controlled Trial) Checklist. [online]

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2022) CASP (Case Control Study) Checklist. [online]

Nooteboom LA, Mulder EA, Kuiper CH, Colins OF, Vermeiren RR (2021) Towards integrated youth care: a systematic review of facilitators and barriers for professionals. Admin Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res 48:88–105

Ryan R, Hill S (2016) How to GRADE the quality of the evidence. Cochrane consumers and communication group 3

Bielas H, Barra S, Skrivanek C, Aebi M, Steinhausen HC, Bessler C, Plattner B (2016) The associations of cumulative adverse childhood experiences and irritability with mental disorders in detained male adolescent offenders. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Mental Health 10:1–10

Goncalves R, Marques M, Cartaxo T, Santos V (2020) Hard routes of mental health in Portugal: what can we offer to an adolescent with serious mental illness and multiple social risk factors? BMJ Case Rep 13:e229120

Mekori E, Halevy L, Ziv SI, Moreno A, Enoch-Levy A, Weizman A, Stein D (2017) Predictors of short-term outcome variables in hospitalised female adolescents with eating disorders. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 21:41–49

Wittchen H-U, Nelson CB, Lachner G (1998) Prevalence of mental disorders and psychosocial impairments in adolescents and young adults. Psychol Med 28:109–126

Hirota T, Paksarian D, He J-P, Inoue S, Stapp EK, Van Meter A, Merikangas KR (2022) Associations of social capital with mental disorder prevalence, severity, and comorbidity among US adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 51:970–981

Reiss F, Meyrose AK, Otto C, Lampert T, Klasen F, Ravens-Sieberer U (2019) Socioeconomic status, stressful life situations and mental health problems in children and adolescents: Results of the German BELLA cohort-study. PLoS ONE 14:e0213700

Rice SM, Simmons MB, Bailey AP, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, Davey CG, Phelan M, Blaikie S, Edwards J (2014) Development of practice principles for the management of ongoing suicidal ideation in young people diagnosed with major depressive disorder. SAGE Open Med 2:2050312114559574

Bühren K, Schwarte R, Fluck F, Timmesfeld N, Krei M, Egberts K, Pfeiffer E, Fleischhaker C, Wewetzer C, Herpertz-Dahlmann B (2014) Comorbid psychiatric disorders in female adolescents with first-onset anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev 22:39–44

Ciao AC, Accurso EC, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Lock J, Le Grange D (2015) Family functioning in two treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 48:81–90

Berona J, Horwitz AG, Czyz EK, King CA (2017) Psychopathology profiles of acutely suicidal adolescents: associations with post-discharge suicide attempts and rehospitalization. J Affect Disord 209:97–104

Esposito C, Spirito A, Boergers J, Donaldson D (2003) Affective, behavioral, and cognitive functioning in adolescents with multiple suicide attempts. Suicide Life Threat Behav 33:389–399

Scott K, Lewis CC, Marti CN (2019) Trajectories of symptom change in the treatment for adolescents with depression study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 58:319–328

Swadi H, Bobier C (2003) Substance use disorder comorbidity among inpatient youths with psychiatric disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 37:294–298

Bartoli F, Cavaleri D, Moretti F, Bachi B, Calabrese A, Callovini T, Cioni RM, Riboldi I, Nacinovich R, Crocamo C, Carrà G (2020) Pre-discharge predictors of 1-year rehospitalization in adolescents and young adults with severe mental disorders: a retrospective cohort study. Medicina (Kaunas) 56:613

Gerdner A, Håkansson A (2022) Prevalence and comorbidity in a Swedish adolescent community sample - gambling, gaming, substance use, and other psychiatric disorders. BMC Psychiatry 22:594

King CA, Knox MS, Henninger N, Nguyen TA, Ghaziuddin N, Maker A, Hanna GL (2006) Major depressive disorder in adolescents: family psychiatric history predicts severe behavioral disinhibition. J Affect Disord 90:111–121

Libby AM, Orton HD, Stover SK, Riggs PD (2005) What came first, major depression or substance use disorder? Clinical characteristics and substance use comparing teens in a treatment cohort. Addict Behav 30:1649–1662

Mueser KT, Taub J (2008) Trauma and PTSD among adolescents with severe emotional disorders involved in multiple service systems. Psychiatr Serv 59:627–634

Peyre H, Hoertel N, Stordeur C, Lebeau G, Blanco C, McMahon K, Basmaci R, Lemogne C, Limosin F, Delorme R (2017) Contributing factors and mental health outcomes of first suicide attempt during childhood and adolescence: results from a nationally representative study. J Clin Psychiatry 78:e622–e630

Rowe CL, Liddle HA, Greenbaum PE, Henderson CE (2004) Impact of psychiatric comorbidity on treatment of adolescent drug abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat 26:129–140

Chan Y-F, Dennis ML, Funk RR (2008) Prevalence and comorbidity of major internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents and adults presenting to substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 34:14–24

Gattamorta KA, Mena MP, Ainsley JB, Santisteban DA (2017) The comorbidity of psychiatric and substance use disorders among Hispanic adolescents. J Dual Diagn 13:254–263

Hoeve M, McReynolds LS, Wasserman GA (2015) Comorbid internalizing and disruptive behavior disorder in adolescents: offending, trauma, and clinical characteristics. Crim Justice Behav 42:840–855

Lehto-Salo P, Närhi V, Ahonen T, Marttunen M (2009) Psychiatric comorbidity more common among adolescent females with CD/ODD than among males. Nord J Psychiatry 63:308–315

Zubrick SR, Hafekost J, Johnson SE, Lawrence D, Saw S, Sawyer M, Ainley J, Buckingham WJ (2016) Suicidal behaviours: prevalence estimates from the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 50:899–910

Göbel K, Ortelbach N, Cohrdes C, Baumgarten F, Meyrose A-K, Ravens-Sieberer U, Scheithauer H (2022) Co-occurrence, stability and manifestation of child and adolescent mental health problems: a latent transition analysis. BMC Psychology 10:1–15

Broersen M, Frieswijk N, Kroon H, Vermulst AA, Creemers DHM (2020) Young patients with persistent and complex care needs require an integrated care approach: baseline findings from the multicenter youth flexible ACT study. Front Psychiatry 11:609120

Häberling I, Baumgartner N, Emery S, Keller P, Strumberger M, Nalani K, Schmeck K, Erb S, Bachmann S, Wöckel L et al (2019) Anxious depression as a clinically relevant subtype of pediatric major depressive disorder. J Neural Transm (Vienna Austria: 1996) 126:1217–1230

Lewinsohn PM, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Rohde P, Gotlib IH, Hops H (1994) Adolescent psychopathology: II. Psychosocial risk factors for depression. J Abnormal Psychol 103:302

Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC (2013) Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiat 70:300–310

Wunderlich U, Bronisch T, Wittchen HU (1998) Comorbidity patterns in adolescents and young adults with suicide attempts. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 248:87–95

Georgiades K, Paksarian D, Rudolph KE, Merikangas KR (2018) Prevalence of mental disorder and service use by immigrant generation and race/ethnicity among US adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 57:280–287

McCarty CA, Russo J, Grossman DC, Katon W, Rockhill C, McCauley E, Richards J, Richardson L (2011) Adolescents with suicidal ideation: health care use and functioning. Acad Pediatr 11:422–426

Merikangas KR, He J-p, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J (2010) Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49:980–989

Merikangas KR, He J-p, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, Georgiades K, Heaton L, Swanson S, Olfson M (2011) Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in US Adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCSA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 50:32–45

Wentz E, Gillberg C, Gillberg IC, Råstam M (2001) Ten-year follow-up of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa: psychiatric disorders and overall functioning scales. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 42:613–622

Becker-Weidman EG, Reinecke MA, Jacobs RH, Martinovich Z, Silva SG, March JS (2009) Predictors of hopelessness among clinically depressed youth. Behav Cogn Psychother 37:267–291

Conway KP, Swendsen J, Husky MM, He J-P, Merikangas KR (2016) Association of lifetime mental disorders and subsequent alcohol and illicit drug use: results from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55:280–288

Woody C, Baxter A, Wright E, Gossip K, Leitch E, Whiteford H, Scott JG (2019) Review of services to inform clinical frameworks for adolescents and young adults with severe, persistent and complex mental illness. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 24:503–528

Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Friedman M, Boerescu DA, Attiullah N, Toba C (2012) How can we use depression severity to guide treatment selection when measures of depression categorize patients differently? J Clin Psychiatry 73:4239

Zimmerman M, Morgan TA, Stanton K (2018) The severity of psychiatric disorders. World Psychiatry 17:258–275

Insel TR (2009) Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact: a strategic plan for research on mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66:128–133

Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, Bagby RM, Brown TA, Carpenter WT, Caspi A, Clark LA (2017) The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): a dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. J Abnorm Psychol 126:454

Manning C, Gregoire A (2006) Effects of parental mental illness on children. Psychiatry 5:10–12

Stowkowy J, Goldstein BI, MacQueen G, Wang J, Kennedy SH, Bray S, Lebel C, Addington J (2020) Trauma in youth at-risk for serious mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis 208:70–76

Backes EP, Bonnie RJ (2019) The promise of adolescence: realizing opportunity for all youth

Coffey C, Veit F, Wolfe R, Cini E, Patton GC (2003) Mortality in young offenders: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 326:1064

Patton GC, Viner R (2007) Pubertal transitions in health. The Lancet 369:1130–1139

Hall RC (1995) Global assessment of functioning: a modified scale. Psychosomatics 36:267–275

Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, Rohde L, Srinath S, Ulkuer N, Rahman A (2011) Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet 378:1515–1525. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11):60827-60821. (Published Online October 17, 2011)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Claudia Pees (Walaeus library Leiden University Medical Centre) for her contribution during the literature search.

Funding

The overarching research project was supported by FNO Geestkracht, the Netherlands (project number: 103601). The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest and that the funder had no any role in the execution and report of this study, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in the review process and preparation of the manuscript. CB is the guarantor, she designed the study protocol and search strategy, selected studies, extracted and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. RS collaborated with CB in the study selection and quality assessment. HE and LAN were involved as independent researchers during the study selection and quality assessment phase. LAN verified the results through reflective discussion meetings. RV, HE, LN and LAN revised the protocol, monitored the review process, and revised the paper. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial or personal relationships with any individuals or organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bansema, C.H., Vermeiren, R.R.J.M., de Soet, R. et al. A systematic review exploring characteristics of youth with severe and enduring mental health problems (SEMHP). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33, 1313–1325 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02216-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02216-6