Abstract

Background and objectives

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) behavior is one of the characteristics of borderline personality disorder (BPD) in adolescents. Prior studies have shown that adolescents with BPD may have a unique pattern of brain alterations. The purpose of this study was to investigate the alterations in brain structure and function including gray matter volume and resting-state functional connectivity in adolescents with BPD, and to assess the association between NSSI behavior and brain changes on neuroimaging in adolescents with BPD.

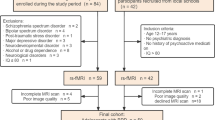

Methods

53 adolescents with BPD aged 12–17 years and 39 age–gender matched healthy controls (HCs) were enrolled into this study. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was acquired with both 3D-T1 weighted structural imaging and resting-state functional imaging. Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) analysis for gray matter volume and seed-based functional connectivity (FC) analysis were performed for assessing gray matter volume and FC. Clinical assessment for NSSI, mood, and depression was also obtained. Correlative analysis of gray matter alterations with self-injury or mood scales were performed.

Results

There were reductions of gray matter volume in the limbic-cortical circuit and default mode network in adolescents with BPD as compared to HCs (FWE P < 0.05, cluster size ≥ 1000). The diminished gray matter volumes in the left putamen and left middle occipital gyrus were negatively correlated with NSSI in adolescents with BPD (r = − 0.277 and P = 0.045, r = − 0.422 and P = 0.002, respectively). Furthermore, there were alterations of FC in these two regions with diminished gray matter volumes (voxel P < 0.001, cluster P < 0.05, FWE corrected).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that diminished gray matter volume of the limbic-cortical circuit and default mode network may be an important neural correlate in adolescent BPD. In addition, the reduced gray matter volume and the altered functional connectivity may be associated with NSSI behavior in adolescents with BPD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- BPD:

-

Borderline personality disorder

- NSSI:

-

Non-suicidal self-injury

- DMN:

-

Default mode network

- VBM:

-

Voxel-based morphometry

- GM:

-

Gray matter

References

Ellison WD et al (2018) Community and clinical epidemiology of borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Clin N Am 41(4):561–573

Mirkovic B et al (2021) Borderline personality disorder and adolescent suicide attempt: the mediating role of emotional dysregulation. BMC Psychiatry 21(1):393

Bohus M et al (2021) Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 398(10310):1528–1540

Levine AZ et al (2020) Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide: differences between those with and without borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 34(1):131–144

Kreisel SH et al (2015) Volume of hippocampal substructures in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 231(3):218–226

Aguilar-Ortiz S et al (2018) Abnormalities in gray matter volume in patients with borderline personality disorder and their relation to lifetime depression: a VBM study. PLoS ONE 13(2):e0191946

Yang X et al (2016) Default mode network and frontolimbic gray matter abnormalities in patients with borderline personality disorder: a voxel-based meta-analysis. Sci Rep 6:34247

Chanen AM et al (2008) Orbitofrontal, amygdala and hippocampal volumes in teenagers with first-presentation borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 163(2):116–125

Richter J et al (2014) Reduced cortical and subcortical volumes in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 221(3):179–186

Brunner R et al (2010) Reduced prefrontal and orbitofrontal gray matter in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder: is it disorder specific? Neuroimage 49(1):114–120

Goodman M et al (2011) Anterior cingulate volume reduction in adolescents with borderline personality disorder and co-morbid major depression. J Psychiatr Res 45(6):803–807

Malejko K et al (2018) Somatosensory stimulus intensity encoding in borderline personality disorder. Front Psychol 9:1853

Dusi N et al (2021) Imaging associations of self-injurious behaviours amongst patients with borderline personality disorder: a mini-review. J Affect Disord 295:781–787

Niedtfeld I et al (2010) Affect regulation and pain in borderline personality disorder: a possible link to the understanding of self-injury. Biol Psychiatry 68(4):383–391

Malejko K et al (2019) Neural signatures of social inclusion in borderline personality disorder versus non-suicidal self-injury. Brain Topogr 32(5):753–761

Kraus A et al (2010) Script-driven imagery of self-injurious behavior in patients with borderline personality disorder: a pilot FMRI study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 121(1):41–51

Wong HM, Chow LY (2011) Borderline personality disorder subscale (Chinese version) of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders: a validation study in Cantonese-speaking Hong Kong Chinese. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 21(2):52–57

Kaufman J et al (1997) Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(7):980–988

Oldfield RC (1971) The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9(1):97–113

Wechsler D (1999) Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio

Wood A et al (1995) Properties of the mood and feelings questionnaire in adolescent psychiatric outpatients: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 36(2):327–334

Li J et al (2018) Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS): factor structure, reliability, and validity. Psychol Assess 30(5):e1–e9

Martin J et al (2013) Psychometric properties of the functions and addictive features scales of the Ottawa Self-Injury Inventory: a preliminary investigation using a university sample. Psychol Assess 25(3):1013–1018

Xiao Q et al (2020) Gray matter voxel-based morphometry in mania and remission states of children with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 268:47–54

Kurth F, Gaser C, Luders E (2015) A 12-step user guide for analyzing voxel-wise gray matter asymmetries in statistical parametric mapping (SPM). Nat Protoc 10(2):293–304

Bennett CM, Wolford GL, Miller MB (2009) The principled control of false positives in neuroimaging. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 4(4):417–422

Nichols TE (2012) Multiple testing corrections, nonparametric methods, and random field theory. Neuroimage 62(2):811–815

Nichols T, Hayasaka S (2003) Controlling the familywise error rate in functional neuroimaging: a comparative review. Stat Methods Med Res 12(5):419–446

Han H, Glenn AL (2018) Evaluating methods of correcting for multiple comparisons implemented in SPM12 in social neuroscience fMRI studies: an example from moral psychology. Soc Neurosci 13(3):257–267

Yi X et al (2023) Altered regional homogeneity and its association with cognitive function in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci 48(1):E1–E10

Xiao Q et al (2023) Altered brain activity and childhood trauma in Chinese adolescents with borderline personality disorder. J Affect Disord 323:435–443

Lan Z et al (2021) Aberrant effective connectivity of the ventral putamen in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Investig 18(8):763–769

Klein M et al (2019) Genetic markers of ADHD-related variations in intracranial volume. Am J Psychiatry 176(3):228–238

Grant JE, Isobe M, Chamberlain SR (2019) Abnormalities of striatal morphology in gambling disorder and at-risk gambling. CNS Spectr 24(6):609–615

Videler AC et al (2019) A life span perspective on borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 21(7):51

Chen CF, Chen WN, Zhang B (2022) Functional alterations of the suicidal brain: a coordinate-based meta-analysis of functional imaging studies. Brain Imaging Behav 16(1):291–304

Kimmel CL et al (2016) Age-related parieto-occipital and other gray matter changes in borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis of cortical and subcortical structures. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 251:15–25

Kluetsch RC et al (2012) Alterations in default mode network connectivity during pain processing in borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69(10):993–1002

Augustine JR (1996) Circuitry and functional aspects of the insular lobe in primates including humans. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 22(3):229–244

Takahashi T et al (2009) Insular cortex volume and impulsivity in teenagers with first-presentation borderline personality disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 33(8):1395–1400

Pico-Perez M et al (2017) Emotion regulation in mood and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of fMRI cognitive reappraisal studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 79(Pt B):96–104

Albert J et al (2019) Response inhibition in borderline personality disorder: neural and behavioral correlates. Biol Psychol 143:32–40

Irle E et al (2007) Size abnormalities of the superior parietal cortices are related to dissociation in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 156(2):139–149

Jin X et al (2016) A Voxel-based morphometric MRI study in young adults with borderline personality disorder. PLoS ONE 11(1):e0147938

Reich DB et al (2019) Amygdala resting state connectivity differences between bipolar II and borderline personality disorders. Neuropsychobiology 78(4):229–237

Villarreal MF et al (2021) Distinct neural processing of acute stress in major depression and borderline personality disorder. J Affect Disord 286:123–133

Choate AM, Fatimah H, Bornovalova MA (2021) Comorbidity in borderline personality: understanding dynamics in development. Curr Opin Psychol 37:104–108

Funding

This research was funded by the Youth Fund of National Natural Science Foundation of China (82201702), National Natural Science Foundation of China (U22A20377), the Youth Science Foundation of Xiangya Hospital: 2020Q20, Xiangya-Peking University, Wei Ming Clinical and Rehabilitation Research Fund (no. xywm2015I35), Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2022JJ30979), and China Post-Doctoral Science Foundation (2022M713536).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiao Qian's main contributions are the collection of patients and control groups, the experimental design and paper writing. Xiaoping Yi’s main contributions are the design of parameter for MRI, guidance of MRI technology, and paper revision. Yan Fu' and Jun Ding's main contributions are magnetic resonance data collection and analysis. Furong Jiang 's main contribution is scale assessment. Zaide Han 's main contribution is the analysis of magnetic resonance data and the guidance of magnetic resonance technology. Zhejia Zhang 's main contribution is the analysis of magnetic resonance data. Yinping Zhang's main contribution is the guidance of magnetic resonance technology. Bihong T. Chen 's main contributions are the guidance of paper writing and revision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedure complied with the ethical standard of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the our Research Ethics Committee (IRB: 2022020227). Written informed consent was obtained from legal guardians of all adolescent participants.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yi, X., Fu, Y., Ding, J. et al. Altered gray matter volume and functional connectivity in adolescent borderline personality disorder with non-suicidal self-injury behavior. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33, 193–202 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02161-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02161-4