Abstract

Short sleep duration has been linked to adverse behavioral and cognitive outcomes in schoolchildren, but few studies examined this relation in preschoolers. We aimed to investigate the association between parent-reported sleep duration at 3.5 years and behavioral and cognitive outcomes at 5 years in European children. We used harmonized data from five cohorts of the European Union Child Cohort Network: ALSPAC, SWS (UK); EDEN, ELFE (France); INMA (Spain). Associations were estimated through DataSHIELD using adjusted generalized linear regression models fitted separately for each cohort and pooled with random-effects meta-analysis. Behavior was measured with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Language and non-verbal intelligence were assessed by the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence or the McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities. Behavioral and cognitive analyses included 11,920 and 2981 children, respectively (34.0%/13.4% of the original sample). In meta-analysis, longer mean sleep duration per day at 3.5 years was associated with lower mean internalizing and externalizing behavior percentile scores at 5 years (adjusted mean difference: − 1.27, 95% CI [− 2.22, − 0.32] / − 2.39, 95% CI [− 3.04, − 1.75]). Sleep duration and language or non-verbal intelligence showed trends of inverse associations, however, with imprecise estimates (adjusted mean difference: − 0.28, 95% CI [− 0.83, 0.27] / − 0.42, 95% CI [− 0.99, 0.15]). This individual participant data meta-analysis suggests that longer sleep duration in preschool age may be important for children’s later behavior and highlight the need for larger samples for robust analyses of cognitive outcomes. Findings could be influenced by confounding or reverse causality and require replication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Healthy sleep is important for children’s physical and mental health and can have a positive influence on future health trajectories of a child [1,2,3]. There is growing evidence that shorter sleep duration is associated with more behavioral problems and poorer cognitive outcomes, especially in school-aged children and adolescents [4,5,6]. Compared with the literature in schoolchildren there is a paucity of studies in younger children of preschool age investigating this relationship [7, 8].

Early childhood is a sensitive period where both brain maturation and sleep habits are developing with continuation throughout childhood [9]. Insufficient sleep in these early years of life can have lasting impacts on a child’s development [8]. Chaput et al. [7] reported in a systematic review of 25 studies that shorter sleep duration was associated with poorer emotional regulation in children aged 0 to 4 years, while for sleep duration and cognitive development (16 studies) results were less clear. Authors concluded that the evidence was mainly based on cross-sectional studies and the high level of between-study heterogeneity made meta-analysis infeasible. Another systematic review of 26 studies on sleep and its relation to behavior and cognition in preschoolers by Reynaud et al. [8] suggested that a higher quantity and quality of sleep was associated with better behavioral outcomes and receptive vocabulary, but found no association for other cognitive outcomes. They concluded that mainly cross-sectional designs (69% of studies), incomplete adjustment for confounders, weak effect sizes and small sample sizes (< 500) limited the validity of the results. Both reviews showed that only a few studies in preschoolers have examined the relationship between sleep duration and later behavioral or cognitive outcomes. They tend to suggest negative associations between sleep duration and internalizing and externalizing problems as well as mixed results for language and non-verbal intelligence in healthy preschoolers [10,11,12,13,14]. With our study involving five European pregnancy and birth cohorts with available data on sleep duration and behavior and cognition, we aimed to examine these previously reported results in a larger sample of preschool aged children. The objective of our study was to investigate the associations between sleep duration in early childhood (~ 3.5 years) and later behavioral problems (internalizing and externalizing) and cognitive outcomes (language and non-verbal intelligence) in children (~ 5 years) using individual participant data.

Methods

Study design and study population

Our study used harmonized data from an international cross-cohort collaboration, the European Union Child Cohort Network established in the Horizon 2020 Project LifeCycle [15,16,17]. A cohort was eligible for our study if it had harmonized preschool sleep at 2 to 4 years of age and behavior (internalizing, externalizing) or/and cognition data (language, non-verbal intelligence) from ages 4 to 6 years. Five cohorts participated: ALSPAC (Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, United Kingdom, n = 4847 eligible children) [18, 19], EDEN (Étude des Déterminants pré et postnatals du développement et de la santé de l’Enfant, France, n = 1015 eligible children) [20], ELFE (Étude Longitudinale Française depuis l’Enfance, France, n = 9100 eligible children) [21], INMA (INfancia y Medio Ambiente Project, Spain, n = 1348 eligible children) [22] and SWS (Southampton Women’s Survey, United Kingdom, n = 134 eligible children) [23]. Further details on each cohort are provided in Online Resource 1.

Preschool sleep duration

All cohorts measured child’s preschool sleep duration using different parental questionnaires (Online Resource 2 Table 1). Parents reported the time their child usually went to sleep (ALSPAC, ELFE, SWS) or to bed (EDEN) and woke up in the morning, as well as the duration of daytime naps. In INMA the parents were asked to provide night and daytime sleep duration.

Cohorts harmonized total sleep duration in hours per day in preschool age (2-4 years) by summing nighttime and daytime sleep durations following a harmonization protocol. Sleep was assessed at a mean age of 3.1 years (SD: 0.1) in SWS, 3.2 years (SD: 0.1) in EDEN, 3.5 years (SD: 0.1, SD: 0.2) in ALSPAC and ELFE, respectively, and 4.4 years (SD: 0.2) in INMA.

To investigate a potential non-linear association between sleep duration and behavioral or cognitive outcomes, we categorized total sleep duration into thirds within each cohort based on tertiles (1st third includes children with the shortest sleep durations).

Internalizing and externalizing behavior problems

Data on behavior was available in three cohorts: ALSPAC, EDEN and ELFE. All cohorts used the parent version of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to measure internalizing and externalizing problems in children. The SDQ is a standardized questionnaire for children from 4 to 16 years with 25 items assessed on a three-point Likert scale [24]. The questionnaire covers five scales: emotional symptoms, peer problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity and prosocial behavior, ranging from 0 to 10 each [24]. The emotional and peer problems subscales were combined into the internalizing score, while the externalizing score includes the scales conduct and hyperactivity problems, as suggested for analyses in low-risk samples in the general population [25]. The SDQ is at least as good in detecting internalizing and externalizing problems compared to semi-structured interviews [26].

We used internalizing and externalizing percentile scores, which range from 0 to 100 and indicate the relative position of each child within his/her cohort and age group [17]. Higher percentile scores indicate more behavioral problems. Behavior was assessed at a mean age of 4.1 years (SD: 0.1) in ALSPAC, 5.5 years (SD: 0.5) in ELFE and 5.6 years (SD: 0.1) in EDEN.

Language and non-verbal intelligence

Data on language and non-verbal intelligence were available in four cohorts: ALSPAC, EDEN, INMA and SWS. In ALSPAC, EDEN and SWS, language and non-verbal intelligence were assessed by trained psychologists using the verbal and performance intelligence scale of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI). The WPPSI is an intelligence test for children aged 2 to 7 years that provides subtests on verbal and performance intelligence domains [27]. The verbal score includes the subtests Information, Vocabulary and Word Reasoning, while the performance score includes the subtests Block Design, Matrix Reasoning and Picture Concepts. In INMA, language and non-verbal intelligence were assessed by a psychologist using the verbal and perceptual-performance domains of the McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities (MSCA) [28]. This instrument is similar to the WPPSI and measures intelligence in children aged 2 to 8 years. The verbal scale consists of the subtests Pictorial Memory, Word Knowledge, Verbal Memory, Verbal Fluency and Opposite Analogies, while the perceptual-performance scale consists of the subtests Block Building, Puzzle Solving, Tapping Sequence, Right-left Orientation, Draw-a-design, Draw-a-child and Conceptual Grouping.

To allow comparison between the two tests, cohort-specific z-scores were calculated and standardized within each cohort to a mean of 100 and a SD of 15, following a harmonization protocol and the lead of other studies [29, 30]. Scores were measured at a mean age of 5.6 years (SD: 0.1) in EDEN and 4.9 years (SD: 0.6) in INMA. In ALSPAC (4.1 years (SD: 0.03)) and SWS (4.4 years (SD: 0.1)) they were measured in a subgroup of children.

Covariates

Potential confounders were identified based on the literature and selected with creating directed acyclic graphs [31,32,33,34] (Online Resource 2 Fig. 1).

The selected variables included sex, birthweight (kg), gestational age (weeks), birth order (first/later born), maternal age at birth (years), maternal education level according to International Standard Classification of Education 97/2011 (low/middle/high) [35, 36], whether the mother was born abroad (yes/no), maternal smoking in pregnancy (yes/no), the predicted equivalized total disposable household income at baseline [37], maternal postpartum depression (yes/no) (not harmonized in INMA/SWS) and child’s passive smoke exposure in the first year of life (yes/no) (not harmonized in INMA). Cohort-specific information on variable collection and missing data is shown in Online Resource 2 Tables 2–3.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed in R (version 3.5.2) using DataSHIELD (version 6.1.0), a data analysis platform that enables federated analysis of data from different cohorts without physically sharing individual-level data [38,39,40].

We performed complete case analysis, including only participants with data on sleep, the specific outcome, and all covariates (Fig. 1). Of the 35,093 eligible children, 34.0% (11,920) had complete data for behavioral analyses, ranging from 20.0% in ALSPAC to 46.1% in EDEN. Of the 22,253 eligible children, 13.4% (2979–2981) had complete data for cognitive analyses, ranging from 3.5% in SWS to 60.2% in INMA.

Flow chart illustrating participants included in the study aN is based on all children with data on sex; bThe original sample for behavior analyses consists of data from ALSPAC, EDEN and ELFE: N = 35,093; cThe original sample for cognition analyses consists of data from ALSPAC, EDEN, INMA and SWS: N = 22,253. The same populations were used in both basic and adjusted models. ALSPAC Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, EDEN Étude des Déterminants pré et postnatals du développement et de la santé de l’Enfant, ELFE Étude Longitudinale Française depuis l’Enfance, INMA Infancia y Medio Ambiente Project, SWS Southampton Women’s Survey

We used two-stage individual participant data (IPD) meta-analysis to study the associations of sleep duration at age 3.5 years with behavioral and cognitive outcomes in children aged 5 years. Sleep duration was analyzed as continuous (decimal hours) and categorical variable (reference: 2nd third) to investigate the possibility that both shorter and longer sleep duration might be associated with the outcomes. For each outcome we constructed two models: a basic model adjusted for sex and age at outcome measurement and a model adjusted for other potential confounders. We conducted generalized linear regression analyses in each cohort and combined the effect estimates using random-effects meta-analysis. For this we used the “rma” command with the restricted maximum likelihood estimator of the “metafor” package in R. Heterogeneity between cohorts was described using I2 and τ2 [41].

We performed several sensitivity analyses: (1) using a one-stage IPD meta-analysis approach, (2) using raw scores of internalizing/externalizing behavior, (3) excluding twins and children with congenital malformation or cerebral palsy as this could possibly effect sleep, behavior and cognition, (4) adjusting for TV watching duration at preschool age, and (5) excluding INMA because of their later sleep measurement.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population in each cohort divided by outcome. In both French cohorts mothers had higher education levels compared to mothers in the other cohorts. Children’s sleep duration differed between countries, with children from France showing a longer sleep duration than children from the UK or Spain. It should be noted, however, that children in INMA were older than children in the other cohorts. Overall mean sleep duration was 11h54min per day (SD: 1h01min) (Online Resource 2 Table 3).

Characteristics of the analyzed and excluded samples were different. Children in the analyzed sample had longer sleep durations, slightly lower behavior percentile scores and higher language or non-verbal intelligence scores than excluded children. Mothers in the analyzed sample had higher education levels, smoked less during pregnancy and were less likely to be born abroad compared to excluded mothers (Online Resource 2 Table 3).

Associations between sleep duration and internalizing and externalizing behavior

Analyses examining the association between sleep duration and behavioral outcomes included 11,920 children from three cohorts (Fig. 1). Figs. 2a, b show that one hour of longer mean sleep duration per day at age 3.5 years was associated with lower internalizing and externalizing behavior percentile scores at 5.1 years (internalizing behavior: mean difference = − 1.27, 95% CI − 2.22, − 0.32; externalizing behavior: mean difference = – 2.39, 95% CI − 3.04, − 1.75). Heterogeneity between cohorts was moderate for internalizing behavior (I2 = 42.0%) and low for externalizing behavior (I2 = 0.0%) in adjusted models. ALSPAC showed a stronger negative association between sleep duration and behavioral outcomes than EDEN or ELFE. There was no evidence for a non-linear association between sleep duration and behavior (Online 2 Resource Table 9). Sensitivity analyses showed similar results (Online Resource 2 Tables 4–5, 8; Figs. 2–8).

Association between total sleep duration per day at mean age of 3.5 years and 2a) internalizing behavior (percentile score), 2b) externalizing behavior (percentile score) at mean age of 5.1 years using two-stage IPD meta-analysis – adjusted models Adjusted for sex of the child, age at outcome measurement, maternal age at birth, maternal education, postpartum depression, mother born abroad, birthweight, gestational age, siblings position, passive smoke exposure in the first year of life, EUSILC-based household income, ALSPAC Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, CI Confidence interval, EDEN Étude des Déterminants pré et postnatals du développement et de la santé de l'Enfant, ELFE Étude Longitudinale Française depuis l'Enfance, N Number of children included in the analysis; I2 and τ2 statistics represent between cohort heterogeneity

Sleep duration and language and non-verbal intelligence

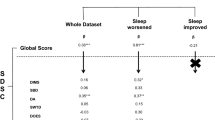

Analyses investigating the association between sleep duration and language or non-verbal intelligence included 2979 and 2981 children, respectively, from four cohorts (Fig. 1). Figures 3a, b show trends of inverse associations between sleep duration at age 3.7 years with either language or non-verbal intelligence scores at 4.9 years, however, estimates were imprecise due to the relative small sample size and confidence intervals included null (language: mean difference = − 0.28, 95% CI − 0.83, 0.27; non-verbal intelligence: mean difference = − 0.42, 95% CI − 0.99, 0.15). Trends were mainly driven by ALSPAC, the oldest cohort. Between cohort heterogeneity in adjusted models was low (language: I2 = 0.0%, non-verbal intelligence: I2 = 4.4%). There was no evidence for a non-linear association between sleep duration and cognitive outcomes (Online Resource 2 Table 9). Sensitivity analyses delivered similar results (Online Resource 2 Tables 6–8; Figs. 9–13).

Association between total sleep duration per day at mean age of 3.7 years and 3a) language (standardized score), 3b) non-verbal intelligence (standardized score) at mean age of 4.9 years using two-stage IPD meta-analysis–adjusted model Adjusted for sex of the child, age at outcome measurement, maternal age at birth, maternal education, mother born abroad, birthweight, gestational age, siblings position, smoking in pregnancy, EUSILC-based household income ALSPAC: Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, CI confidence interval, EDEN: Étude des Déterminants pré et postnatals du développement et de la santé de l’Enfant, INMA INfancia y Medio Ambiente Project, SWS Southampton Women’s Survey, N number of children included in the analysis, I2 and τ2 statistics represent between cohort heterogeneity

Discussion

In this meta-analysis of IPD from five European cohorts, we observed that a longer mean sleep duration per day in preschool age was associated with lower subsequent scores of internalizing and externalizing behavior at 5 years of age, while the associations between sleep duration and language or non-verbal intelligence were imprecise with trends toward an inverse association.

Our results extend the knowledge from the few available longitudinal studies on the association of sleep duration with behavior in normally developing preschoolers [10,11,12]. In a Norwegian cohort (N = 32,662) a dose–response association was found between parent-reported short sleep duration (≤ 10 h, 11-12 h vs. ≥ 13 h) at 18 months and the risk of internalizing and externalizing problems at age 5 years assessed by the Child Behavior Checklist [10]. Jansen et al. [11] showed that parent-reported sleep duration of less than 12.5 h at age 2 years was a risk factor for anxiety or depressive symptoms at age 3 years measured with the Child Behavior Checklist in 4782 children. In a sample of 1492 children a short sleep duration pattern before the age of 3.4 years was associated with higher hyperactivity-impulsivity scores at age 6 years [12]. All mentioned studies adjusted for pre-existing behavioral symptoms, to account at least partially for reverse causality, because pre-existing behavioral and cognitive traits are likely to influence sleep duration and correlate with equivalent traits at older ages [42]. Outcome at time of exposure measurement and exposure at time of outcome measurement were not available in the present study. Outcome misclassification needs to be additionally considered, as parents of children with more behavioral problems at an earlier age might report sleep duration as shorter than it is. This should be taken into account when interpreting our results.

The effect estimates obtained for internalizing and externalizing behavior percentile scores in our study were relatively small. Even though this difference may not be clinically relevant, it may reflect large differences at the population-level. Experimental studies with young children showed that even light levels of sleep deprivation over just a few days can impair the ability of emotion- and self-regulation, which are potential risk factors for problem behavior [43, 44].

There are some biological mechanisms that may explain the associations of sleep and behavioral outcomes. A systematic review of sleep and its associations with brain functions and structures in children suggested for example that shorter sleep duration is associated with greater reactivity in brain regions that are involved in emotion processing [45]. Also studies in adults showed that sleep deprivation led to a stronger amygdala response to negative and neutral emotional images [46, 47]. This could result in less cognitive control over emotion processing leading to more irritability and negative affect [48]. In our study, we found an association with internalizing and externalizing problems which are closely related to emotional processes.

Previous studies reported mixed results of the association between sleep duration and cognition in preschool children [12,13,14, 49]. Touchette et al. [12] reported that children with persistently short sleep durations during preschool age scored lower on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary test at age 5 years, and children with a short sleep duration pattern before the age of 3.4 years had lower non-verbal intelligence skills assessed with the Wechsler Intelligence Scale at age 6 years. In contrast to our study, where only one time-point was analyzed, Touchette et al. [12] measured sleep at five time-points and created sleep patterns. Another study in 2800 children reported that children sleeping within the recommended sleep duration range of 11 to 14 h at age 2 years had better non-verbal intelligence as well as language scores at age 6 years than children with shorter or longer sleep [14]. Authors concluded that children with average sleep duration also most likely have normal levels in other developmental areas such as cognitive outcomes. Dionne et al. [13] showed in a sample of 1029 children that parental reports of night sleep duration at 30 months were not associated with receptive vocabulary assessed by the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test at age 5 years, but with a higher day/night sleep ratio at 18 months, indicating less mature sleep consolidation. A study in 194 children showed a trend of an inverse association of mother-reported sleep duration at 24 months with verbal and non-verbal intelligence at age 3 years measured with the WPPSI [49].

The different findings show that further longitudinal studies with multiple sleep duration measurements, other sleep variables as day/night sleep ratio and larger sample sizes are needed to get a clearer picture of this potential relationship.

Strengths and limitations

Our study’s major strength is the federated analysis approach which allowed analyses of IPD from five cohorts including children from three European countries. The consistent harmonization of variables between cohorts as well as the consistent adjustment for confounders in the analyses reduced between-study heterogeneity and strengthens reproducibility of the findings across cohorts. Another strength is that outcomes were measured with validated questionnaires (SDQ) and tests performed by trained psychologists (WPPSI, MCSA).

One limitation of our study is the complete case analysis. For behavioral analyses 34.0% of the original sample contributed, whereas this was just 13.4% for cognitive outcomes, in part because language and non-verbal intelligence were measured only in subgroups in ALSPAC and SWS. This potential loss of information leads to loss of statistical power and increases the uncertainty of the estimates. Complete case analysis assumes that the chance of being a complete case is independent of the outcome after adjusting for covariates [50]. We acknowledge that with the amount of missing data and the demonstrated differences between those included and not, it is plausible that selection bias has had some influence on our findings.

Sleep duration was based on parental reports in all cohorts. Studies have shown the tendency of parents to overestimate their child’s real sleep duration compared to device-based measured sleep [51, 52]. While questions used to measure sleep duration were different across cohorts, the mean sleep duration in our study was similar to values in a meta-analysis of preschoolers (mean 11h54min) [53] and is within the range of 10 to 13 h recommended by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine for children aged 3 to 5 years [3], suggesting that it is rather cultural background that might play an important role in the specific country differences. The variation in sleep duration between the three countries that contributed to this study, are consistent with other studies showing that children from northern and middle European countries sleep longer than children in southern or eastern Europe [54, 55].

Methodological aspects in data acquisition might have affected the measured sleep duration, outcomes and covariates. However, great efforts were undertaken to harmonize data between cohorts [15,16,17]. The variable catalog with data source information is openly available at https://data-catalogue.molgeniscloud.org/catalogue/catalogue/#/networks-catalogue/EUChildNetwork/variables. The downside of the federated analysis approach is that it tends to use the lowest common denominator of available information for data harmonization, which can lead to residual confounding. Many confounders were reduced to binary variables (for example passive smoking (yes/no), birth order (first/later born) etc.) and ethnicity was approximated by whether the mother was born abroad or not, which will capture only a modest part of the complex influence of confounders on child sleep and outcomes.

Conclusion

Using IPD from five European cohorts, we showed that longer sleep duration at 3.5 years of age was associated with both lower internalizing and externalizing problem behavior scores at 5 years of age, while the evidence of an association of sleep duration with either language or non-verbal intelligence was imprecise. Our results suggest that longer sleep duration at early preschool ages may be important for later behavioral outcomes. These findings could be due to confounding or reverse causality and need replication.

Data availability

The data used in the analysis is not freely available as access is managed by each individual cohort. Researchers who want to use data from the EU Child Cohort Network can send a request to lifecycle@erasmusmc.nl (more information under https://lifecycle-project.eu/).

Code availability

Statistical analysis was performed in R (version 3.5.2) using DataSHIELD (version 6.1.0).

Abbreviations

- ALSPAC:

-

Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EDEN:

-

Étude des Déterminants pré et postnatals du développement et de la santé de l’Enfant

- ELFE:

-

Étude Longitudinale Française depuis l’Enfance

- IPD:

-

Individual participant data

- INMA:

-

INfancia y Medio Ambiente Project

- MSCA:

-

McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SDQ:

-

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- SWS:

-

Southampton Women’s Survey

- WPPSI:

-

Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence

References

Gruber R, Carrey N, Weiss SK et al (2014) Position statement on pediatric sleep for psychiatrists. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 23(3):174–195

Tarokh L, Hamann C, Schimmelmann BG (2014) Sleep in child and adolescent psychiatry: overlooked and underappreciated. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 23(6):369–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0554-7

Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C et al (2016) Consensus statement of the American academy of sleep medicine on the recommended amount of sleep for healthy children: methodology and discussion. J Clin Sleep Med 12(11):1549–1561. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6288

Astill RG, Van der Heijden KB, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Van Someren EJ (2012) Sleep, cognition, and behavioral problems in school-age children: a century of research meta-analyzed. Psychol Bull 138(6):1109–1138. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028204

Chaput JP, Gray CE, Poitras VJ et al (2016) Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 41(6 Suppl 3):S266-282. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0627

Matricciani L, Paquet C, Galland B et al (2019) Children’s sleep and health: a meta-review. Sleep Med Rev 46:136–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2019.04.011

Chaput JP, Gray CE, Poitras VJ et al (2017) Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in the early years (0–4 years). BMC Public Health 17(Suppl 5):855. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4850-2

Reynaud E, Vecchierini MF, Heude B et al (2018) Sleep and its relation to cognition and behaviour in preschool-aged children of the general population: a systematic review. J Sleep Res 27(3):e12636. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12636

Jiang F (2019) Sleep and Early Brain Development. Ann Nutr Metab 75(Suppl 1):44–54. https://doi.org/10.1159/000508055

Sivertsen B, Harvey AG, Reichborn-Kjennerud T et al (2015) Later emotional and behavioral problems associated with sleep problems in toddlers: a longitudinal study. JAMA Pediatr 169(6):575–582. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0187

Jansen PW, Saridjan NS, Hofman A et al (2011) Does disturbed sleeping precede symptoms of anxiety or depression in toddlers? The Generation R Study. Psychosom Med 73(3):242–249. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820a4abb

Touchette E, Petit D, Seguin JR et al (2007) Associations between sleep duration patterns and behavioral/cognitive functioning at school entry. Sleep 30(9):1213–1219. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/30.9.1213

Dionne G, Touchette E, Forget-Dubois N et al (2011) Associations between sleep-wake consolidation and language development in early childhood: a longitudinal twin study. Sleep 34(8):987–995. https://doi.org/10.5665/SLEEP.1148

Kocevska D, Rijlaarsdam J, Ghassabian A et al (2017) Early childhood sleep patterns and cognitive development at age 6 years: the Generation R Study. J Pediatr Psychol 42(3):260–268. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsv168

Jaddoe VWV, Felix JF, Andersen AN et al (2020) The LifeCycle Project-EU Child Cohort Network: a federated analysis infrastructure and harmonized data of more than 250,000 children and parents. Eur J Epidemiol 35(7):709–724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-020-00662-z

Pinot de Moira A, Haakma S, Strandberg-Larsen K et al (2021) The EU Child Cohort Network’s core data: establishing a set of findable, accessible, interoperable and re-usable (FAIR) variables. Eur J Epidemiol 36:565–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00733-9

Nader JL, Lopez-Vicente M, Julvez J et al (2021) Cohort description: Measures of early-life behaviour and later psychopathology in the lifecycle project - EU child cohort network. J Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20210241

Boyd A, Golding J, Macleod J et al (2013) Cohort profile: the ‘children of the 90s’–the index offspring of the avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Int J Epidemiol 42(1):111–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys064

Fraser A, Macdonald-Wallis C, Tilling K et al (2013) Cohort profile: the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children: ALSPAC mothers cohort. Int J Epidemiol 42(1):97–110. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys066

Heude B, Forhan A, Slama R et al (2016) Cohort Profile: The EDEN mother-child cohort on the prenatal and early postnatal determinants of child health and development. Int J Epidemiol 45(2):353–363. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv151

Charles MA, Thierry X, Lanoe JL et al (2020) Cohort profile: the French national cohort of children (ELFE): birth to 5 years. Int J Epidemiol 49(2):368–369j. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz227

Guxens M, Ballester F, Espada M et al (2012) Cohort profile: the INMA–INfancia y Medio Ambiente–(Environment and Childhood) project. Int J Epidemiol 41(4):930–940. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr054

Inskip HM, Godfrey KM, Robinson SM et al (2006) Cohort profile: the Southampton Women’s Survey. Int J Epidemiol 35(1):42–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyi202

Goodman R (1997) The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38(5):581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Goodman A, Lamping DL, Ploubidis GB (2010) When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): data from British parents, teachers and children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 38(8):1179–1191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x

Goodman R, Scott S (1999) Comparing the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the Child Behavior Checklist: is small beautiful? J Abnorm Child Psychol 27(1):17–24. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022658222914

Wechsler D. (1967) Manual for the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio: TX: The Psychological Corporation

McCarthy D (1972) McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities. Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX

Levie D, Korevaar TIM, Bath SC et al (2018) Thyroid function in early pregnancy, child IQ, and autistic traits: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 103(8):2967–2979. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-00224

Boucher O, Julvez J, Guxens M et al (2017) Association between breastfeeding duration and cognitive development, autistic traits and ADHD symptoms: a multicenter study in Spain. Pediatr Res 81(3):434–442. https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2016.238

Letourneau NL, Duffett-Leger L, Levac L et al (2011) Socioeconomic status and child development: a meta-analysis. J Emot Behav Disord 21(3):211–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426611421007

Rogers A, Obst S, Teague SJ et al (2020) Association between maternal perinatal depression and anxiety and child and adolescent development: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 174(11):1082–1092. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2910

Zhang H, Lee ZX, White T, Qiu A (2020) Parental and social factors in relation to child psychopathology, behavior, and cognitive function. Transl Psychiatry 10(1):80. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-0761-6

Lipsky AM, Greenland S (2022) Causal directed acyclic graphs. JAMA 327(11):1083-1084. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.1816

Unesco (1997) International Standard Classification of Education, ISCED 1997

Unesco (2011) International Standard Classification of Education, ISCED 2011

Pizzi C, Richiardi M, Charles MA et al (2020) Measuring child socio-economic position in birth cohort research: the development of a novel standardized household income indicator. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051700

Gaye A, Marcon Y, Isaeva J et al (2014) DataSHIELD: taking the analysis to the data, not the data to the analysis. Int J Epidemiol 43(6):1929–1944. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu188

Wilson RC, Butters OW, Avraam D et al (2017) DataSHIELD – new directions and dimensions. Data Science Journal 16(21):1–21. https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2017-021

Budin-Ljosne I, Burton P, Isaeva J et al (2015) DataSHIELD: an ethically robust solution to multiple-site individual-level data analysis. Public Health Genomics 18(2):87–96. https://doi.org/10.1159/000368959

Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DGe. (2021) Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT TJ, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editor. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 62 (updated February 2021): Cochrane

Sourander A, Helstela L (2005) Childhood predictors of externalizing and internalizing problems in adolescence. A prospective follow-up study from age 8 to 16. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 14(8):415–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-005-0475-6

Berger RH, Miller AL, Seifer R et al (2012) Acute sleep restriction effects on emotion responses in 30- to 36-month-old children. J Sleep Res 21(3):235–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00962.x

Miller AL, Seifer R, Crossin R, Lebourgeois MK (2015) Toddler’s self-regulation strategies in a challenge context are nap-dependent. J Sleep Res 24(3):279–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12260

Dutil C, Walsh JJ, Featherstone RB et al (2018) Influence of sleep on developing brain functions and structures in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 42:184–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2018.08.003

Yoo SS, Gujar N, Hu P et al (2007) The human emotional brain without sleep-a prefrontal amygdala disconnect. Curr Biol 17(20):R877-878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.007

Krause AJ, Simon EB, Mander BA et al (2017) The sleep-deprived human brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 18(7):404–418. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2017.55

Walker MP, van der Helm E (2009) Overnight therapy? the role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychol Bull 135(5):731–748. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016570

Plancoulaine S, Stagnara C, Flori S et al (2017) Early features associated with the neurocognitive development at 36 months of age: the AuBE study. Sleep Med 30:222–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.10.015

Hughes RA, Heron J, Sterne JAC, Tilling K (2019) Accounting for missing data in statistical analyses: multiple imputation is not always the answer. Int J Epidemiol 48(4):1294–1304. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz032

Dayyat EA, Spruyt K, Molfese DL, Gozal D (2011) Sleep estimates in children: parental versus actigraphic assessments. Nat Sci Sleep 3:115–123. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S25676

Werner H, Molinari L, Guyer C, Jenni OG (2008) Agreement rates between actigraphy, diary, and questionnaire for children’s sleep patterns. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 162(4):350–358. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.162.4.350

Galland BC, Taylor BJ, Elder DE, Herbison P (2012) Normal sleep patterns in infants and children: a systematic review of observational studies. Sleep Med Rev 16(3):213–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2011.06.001

Hense S, Barba G, Pohlabeln H et al (2011) Factors that influence weekday sleep duration in European children. Sleep 34(5):633–639. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/34.5.633

Guerlich K, Gruszfeld D, Czech-Kowalska J et al (2022) Sleep duration and problem behaviour in 8-year-old children in the Childhood Obesity Project. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31:519–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01731-8

Acknowledgements

All study-specific acknowledgments and funding are presented in Online Resource 1. Additionally, the authors would like to acknowledge all people involved in the DataSHIELD project and the Molgenis Team.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research (LifeCycle Project ID: ECCNLC201914) was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement N: 733206, LifeCycle project. Kathrin Guerlich was granted a LifeCycle Fellowship (Grant Agreement N: 733206, LifeCycle project). Berthold Koletzko is the Else Kröner Seniorprofessor of Paediatrics at LMU – University of Munich, financially supported by Else Kröner-Fresenius-Foundation, LMU Medical Faculty and LMU University Hospital. Deborah A Lawlor and Ahmed Elhakeem work in a Unit that receives support from the University of Bristol and UK Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00011/6). Deborah A Lawlor is a British Heart Foundation Chair (CH/F/20/90003) and a National Institute of Health Research Senior Investigator (NF-0616–10102). Mònica Guxens is funded by a Miguel Servet II fellowship (CPII18/00018) awarded by the Spanish Institute of Health Carlos III. Jordi Julvez holds Miguel Servet-II contract (CPII19/00015) awarded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Co-funded by European Social Fund "Investing in your future"). Tim Cadman was funded a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship. Funding details for each cohort are provided in Online Resource 1. No funder had any influence on the study design, data collection, statistical analyses or interpretation of findings. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily of any funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KG made substantial contributions to the design of the work, analyzed the data and drafted and finalized the manuscript. DA, TC, LC, M-AC, AE, SF-B, MG, BH, JI, HI, JJ, DAL, MM, TS, JS, MT made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and critically reviewed the manuscript. BK made substantial contributions to the design of the work and critically reviewed the manuscript. SP and VG made substantial contributions to the design of the work, participated in the data analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Deborah A Lawlor has received support from Roche Diagnostics and Medtronic Ltd for research unrelated to that presented here.

All other authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

All research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participating cohorts received ethical approval from their local ethics committees (more details in Online Resource 1).

Consent to participate

Parents and children gave their written informed consent.

Consent to publish

Representatives from all participating cohorts reviewed the manuscript and gave consent for publication.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guerlich, K., Avraam, D., Cadman, T. et al. Sleep duration in preschool age and later behavioral and cognitive outcomes: an individual participant data meta-analysis in five European cohorts. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33, 167–177 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02149-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02149-0