Abstract

Objectives

We present this systematic review and meta-analyses to evaluate current evidence on the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress in patients with oral lichen planus and their magnitude of association.

Material and methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, PsycInfo, and Google Scholar for studies published before January 2021. We evaluated the quality of studies using a specific method for systematic reviews addressing prevalence questions, designed by the Joanna Briggs Institute. We carried out meta-analyses and performed heterogeneity, subgroups, meta-regression, and small-study effects analyses.

Results

Fifty-one studies (which recruited 6,815 patients) met the inclusion criteria. Our results reveal a high prevalence of depression (31.19%), anxiety (54.76%), and stress (41.10%) in oral lichen planus. Furthermore, OLP patients presented a significantly higher relative frequency than control group without OLP for depression (OR = 6.15, 95% CI = 2.73–13.89, p < 0.001), anxiety (OR = 3.51, 95% CI = 2.10–5.85, p < 0.001), and stress (OR = 3.64, 95% CI = 1.48–8.94, p = 0.005), showing large effect sizes. Subgroups meta-analyses showed the relevance of the participation of psychologists and psychiatrists in the diagnosis of depression, anxiety, and stress in patients with OLP. Multivariable meta-regression analysis showed the importance of the comorbidity of depression-anxiety in patients with OLP.

Conclusions

Our systematic review and meta-analysis show that patients with OLP suffer a higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress, being more frequent than in general population.

Clinical relevance

In the dental clinic, especially dentists should be aware of depression, anxiety, and stress in OLP patients to achieve a correct referral.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease that presents with white reticular lesions accompanied or not by erythematous, erosive, plaque, bullous, or papular lesions [1]. The importance of the disease lies in its frequency, affecting 1% of the general population as recently has been documented, with a higher prevalence in Europe (1.38%) [2]. Furthermore, OLP is now considered undoubtedly an oral potentially malignant disorder with a risk of progression to cancer in 2.28% of the affected population [1, 3,4,5].

A widely recognized and generally accepted feature of OLP is related to its possible association with some psychological disorders [6, 7] among which are essentially anxiety, depression, and stress [8,9,10]. A systematic review has reported the presence of psychological disorders in patients suffering from OLP [11], and more recently, a meta-analysis corroborates the association between cutaneous and oral lichen planus with depression and anxiety [12]. The aforementioned meta-analysis [12], the only one published to date, even being the work that provides the greatest scientific evidence on the subject, presents critically low methodological quality. As will be discussed later, there is significant bias in the selection of included papers that impacts on the strength of this review.

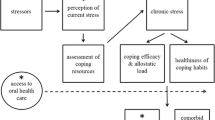

Encountering cases with OLP is not uncommon in clinical dental practice. The management of OLP has multiple aspects, all of which are important and complex, such as its chronic nature and consequently the frequent need to prescribe prolonged treatments with immunosuppressants, i.e., topical corticosteroids; its potential to evolve into oral cancer, requiring lifelong follow-up; its association with systemic diseases, among which are diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hepatitis C, and some autoimmune diseases Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and thymoma [13,14,15,16,17]; and also its association with psychological disorders. The recognition of psychological disorders in patients with OLP is especially complex due to the difficulty to exploring this aspect in the dental clinic. As a consequence of the reticence of many patients to reveal or recognize their psychiatric diseases, particularly if this topic is not specifically investigated, the patient will probably keep it hidden. Furthermore, many patients with OLP, even admitting to being subjected to an altered emotional state, have not previously been diagnosed by a psychologist or a psychiatrist. In addition, probably, it is likely that patients, due to fear of the adverse effects of the treatment or even embarrassment, do not make the decision to ask for medical advice. Finally, it must be recognized that many dentists may not feel authorized or qualified, or even not knowing how to refer a patient for a psychological evaluation. Another relevant dimension concerns the extent to which it could affect the emotional state of the patient with OLP to be informed of the risk of developing oral cancer.

All these questions justify carrying out a thorough investigation on the subject with the aim of knowing, based on scientific evidence, what is the real magnitude of the problem, what are the clinical aspects of a patient with OLP that should make the dentist suspect the presence of an associated psychological disorder, and what should be the attitude in the management of these patients in the dental clinic. To achieve these objectives, a systematic review and meta-analysis have been carried out to qualitatively and quantitatively evaluate the prevalence and magnitude of the association between OLP and psychological disorders, as well as the associated factors, following strict criteria validated in international consensus that guarantee obtaining of results based on scientific methodology leading to a high quality of evidence.

Material and methods

Framework design

This systematic review and meta-analysis closely followed the criteria of Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [18] and Joanna Briggs Institute (University of Adelaide, Australia) for systematic reviews formulating focused questions of prevalence and for proportion meta-analyses. It was also designed, conducted, and validated according to A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR2) high standards [19], and reporting complied with MOOSE and PRISMA guidelines [20, 21].

To assess the prevalence of mental disorders among OLP patients, Condition, Context and Population (CoCoPop) framework was designed: condition, proportion of cases with depression, anxiety, and/or stress, expressed as percentage; context, their associated characteristics (i.e., geographical area, suspicion method for depression, anxiety, and stress, specialist implied in the diagnosis of metal disorders, publication language, sex, age, tobacco, alcohol, type of OLP, year of publication, risk of bias, and human development index); population, participants with OLP diagnosed by clinical and/or histopathological criteria.

To assess the magnitude of association between mental disorders and OLP, PECOTS framework was designed: population, participants with OLP diagnosed by clinical and/or histopathological criteria; exposure, cases with depression, anxiety, and/or stress; comparison, healthy controls (i.e., non-affected by the precedent mental disorders); outcome, magnitude of association using odds ratios as effect size measure, with 95% confidence intervals; timing, no restrictions by follow-up period or publication date; setting, observational studies published in any language.

Protocol

In order to minimize risk of bias and improve the transparency, precision, and integrity of our systematic review and meta-analysis, a protocol on its methodology has been a priori designed and submitted in PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews (www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO; registration code CRD42020222371). Our protocol also complied with PRISMA-P statement in order to ensure scientific rigor [22].

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE (through PubMed), Embase, PsycInfo, Web of Science, and Scopus databases for studies published before the search date (upper limit, January 2021), with no lower date limit. Searches were built to maximize sensitivity and combined thesaurus terms used by the databases (i.e., MeSH and Emtree) with free terms (Table 1, Appendix p.5). Only keywords synonyms or related to oral lichen planus were included, to retrieve the maximum number of possible registers. An additional screening was performed handsearching the reference lists of retrieved included studies and using Google. All references were managed using Mendeley v.1.19.4 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands); duplicates were also removed via this software.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were the following: (1) original studies, without publication language (studies published in English [n = 47], Chinese [n = 1], French [n = 1], Italian [n = 1], and Spanish [n = 1] were identified and included) or date restrictions; (2) studies analyzing the prevalence of depression, anxiety, or stress in patients with OLP (with or without a control group), and/or the magnitude of association (control group needed); (3) observational study design; (4) when results derived from the same study population, we included the most recently reported or those providing more data; the use of the same population in different studies was determined by verifying the name and affiliation of authors, location of the study, source of patients, and recruitment period.

The exclusion criteria were the following: (1) retractions, reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, editorials, letters, meeting abstracts, personal comments, or book chapters; (2) animal research or in vitro studies; (3) absence of healthy control group for the magnitude of association analysis; (4) lack of essential data for statistical analyses; (5) presence of aggregated data for OLP and cutaneous or genital lichen planus.

Study selection process

Eligibility criteria were applied independently by two authors (TDPC and PRG). Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus with a third author (MAGM). Evaluators were first trained and calibrated for the process of identification and selection of studies, performing several screening rounds (50 papers each). The reliability of the study selection process was estimated calculating inter-agreement scores and Cohen’s kappa (κ) values. Articles were selected in two stages: screening titles and abstracts for those apparently meeting inclusion criteria (stage I, 100% of agreement; κ = 1.00), and reading the full-text of previously selected articles, excluding those not meeting eligibility criteria (stage II, 99.70% of agreement; κ = 0.95).

Data extraction

One author (TDPC) independently extracted data from the selected articles. A standardized full-text analysis was performed using Excel v.16.46 spreadsheets (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). Datasets were crosschecked by a second author (PRG). All discrepancies were also solved by consensus. Data were gathered on the first, last, and corresponding author; publication year; country and continent; source of patient recruitment; recruitment and follow-up periods; sample size; absolute and relative frequencies of mental disorders; study design; location and clinical appearance of lesions; diagnostic criteria for OLP; suspicion method for mental disorders; specialists implied; sex; age; and tobacco and alcohol consumption.

Evaluation of quality and risk of bias of primary-level studies

Two authors (TDPC and PRG) evaluated the quality and risk of using a specific method for systematic reviews addressing prevalence questions (Joanna Briggs Institute, University of Adelaide, Australia) [23]. The following items were critically appraised: (1) Was the sample representative of the target population?; (2) Were study participants recruited in an appropriate way?; (3) Was the sample size adequate?; (4) Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail?; (5) Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample?; (6) Were objective, standard criteria used for the measurement of the condition?; (7) Was the condition measured reliably?; (8) Was the statistical analysis appropriate?; (9) Were all important confounding factors/subgroups/differences identified and accounted for?; (10) Were subpopulations identified using objective criteria?. Each domain was categorized as “Yes” (low RoB), “Unclear” (moderate RoB), and “No” (High RoB). Furthermore, a specific score was attributed to individual items (low RoB = 3; moderate RoB = 2; high RoB = 1) to obtain an overall RoB estimate.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of mental disorders among patients with OLP was calculated extracting the raw numerators (number of cases with depression, anxiety, and stress) and denominators (patients with OLP). These proportions and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CI), constructed using the score method [24], were meta-analyzed to obtain pooled proportions (PP) expressed as percentage. The influence of studies with extreme values (0, 100, or close to 0 or 100) was minimized by using Freeman-Tukey double-arcsine transformation, to stabilize the variance of the study-specific prevalence [25]. The magnitude of association between OLP and mental disorders (i.e., depression, anxiety, and stress) was also separately explored estimating and combining odds ratios (OR) with 95% CI. All meta-analyses were performed using random-effects models, weighed by the inverse-variance based on the DerSimonian and Laird method [26], to account for the possibility that there are different underlying results among study subpopulations (e.g., differences in geographic areas, sex, age, suspicion method, etc.). Forest plots were constructed to graphically represent the overall effect and for subsequent visual inspection analyses (p < 0.05 was considered significant).

Heterogeneity between studies was assessed applying the χ2-based Cochran’s Q test (given its low statistical power, p < 0.10 was considered significant). I2 statistic was also quantified (values of 50–75% were interpreted as moderate-to-high degree of inconsistency across the studies) to estimate what proportion of the variance in observed effects reflects variation in true effects, rather than sampling error [27, 28]. Preplanned stratified meta-analyses were performed to identify potential sources of heterogeneity and to determine subgroups-specific prevalence [29]. The potential effect of study covariates on the prevalence of mental disorders in OLP was also explored using meta-regression [30]. We performed univariable and multivariable random-effects meta-regression analyses using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method [31]. The covariates identified to be statistically significant (p < 0.05) in a first-step univariable analysis were included in a multivariable meta-regression model. Considering the low number of studies with data available for some meta-regression analyses, the p values were calculated using a permutation test based on Monte Carlo simulations (1,000 permutations) [32]. Weighted bubble plots were also constructed to graphically represent the fitted meta-regression lines.

Finally, secondary analyses were carried out to test the stability and reliability of meta-analysis results. Therefore, sensitivity analyses were carried out to explore the influence individual primary-level studies on the pooled estimates [33]. For this, the meta-analyses were repeated sequentially, omitting one study at a time (“leave-one-out” method). Furthermore, funnel plots were constructed to evaluate small-study effects, such as publication bias [34]. In addition, the Egger [35] regression test was applied performing a linear regression of the effect estimates on their standard errors, weighting by 1/(variance of the effect estimate), considering a pEgger value of < 0.10 as significant. In addition, trying to confirm the absence of small-study effects, a nonparametric “trim and fill” method was used to identify and potentially correct the funnel plot asymmetry [36]. The statistical analysis was designed by PRG and executed by TDPC, using Stata software (version 16.1, Stata Corp, USA).

Validation of methodological quality

Two independent authors (PRG and TDPC) critically designed and validated the methodology followed in this systematic review and meta-analysis using AMSTAR2 tool [19], created as an instrument to develop, evaluate, and validate high-quality systematic reviews through 16 items (the 16-item checklist is listed in the Appendix, pp. 62–65). An overall rating is obtained based on weaknesses in critical domains (i.e., items 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15) and noncritical domains. The overall confidence on the methodology of the systematic review is rated in one of the four levels: “High,” “Moderate,” “Low,” and “Critically low” (the full explanation is also listed in the Appendix, p. 66).

Results

Literature search

The flow diagram (Fig. 1) illustrates the results of the study selection process. We identified a total of 12,917 records published before January 2021 (Appendix Table 1, p. 5): 3,578 from PubMed, 3,227 from Embase, 2,931 from Web of Science, 3,171 from Scopus, 10 from PsycInfo, and 3 from handsearching methods (2 from the bibliographic reference lists [37, 38] and one from Google Scholar [6]). After removal of duplicate records, 4,925 were potentially eligible. Once the titles and abstracts had been screened, 1,670 studies were evaluated in full-text, of which 1,445 studies did not comply with the inclusion criteria. Finally, 51 studies were included in the qualitative and quantitative analysis (references for included and excluded studies—with their reasons for exclusion reasons—are listed in the Appendix, pp. 69–73).

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the general characteristics of the 51 meta-analyzed studies, which recruited 6,815 patients. Supplementary Table 2 displays in more detail the characteristics and variables collected (Appendix Table 2, pp. 6–8).

Thirty-three studies (4,031 patients) reported data on the prevalence of depression in OLP patients. Regarding the prevalence by continents, 10 studies (441 patients) took place in Asia, 16 (2,902 patients) in Europe, 3 (170 patients) in North America, 3 (148 patients) in South America, and only one multicentric across various continents. Besides, prevalence by depression suspicion method was also performed: 6 studies (503 patients) diagnosed this disorder using hospital and anxiety depression scale (HADS), 5 studies (163 patients) by depression, anxiety and stress scale-21 items (DASS-21), 4 studies (948 patients) by anamnesis, 4 studies (670 patients) by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), 2 studies (161 patients) by Beck depression inventory II (BDI-II), 1 study (100 patients) by Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), and another study (91 patients) by Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D). However, 8 studies (1,280 patients) did not describe how the suspicion was made and 2 studies (115 patients) used multiple tests. Depression was diagnosed in collaboration with a psychologist in 2 studies (161 patients), with a psychiatrist in 3 studies (169 patients), and with the rest of specialists—including dentists, dermatologists, and/or oral medicine/pathologists—in 28 studies (3,701 patients).

Thirty-one studies (3,336 patients) reported data on the prevalence of anxiety in OLP patients. With regard to the prevalence by continents, 9 studies (535 patients) took place in Asia, 16 (2,236 patients) in Europe, 1 (10 patients) in North America, 4 (185 patients) in South America, and only one multicentric across various continents. In addition, prevalence by anxiety suspicion method was also performed: 6 studies (348 patients) by State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), 5 (703 patients) by Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), another 5 (458 patients) by HADS, and further 5 (163 patients) by DASS-21 test. Moreover, 2 studies (117 studies) diagnosed this disorder by anamnesis and 2 more (274 patients) by Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS). However, 4 studies (1,101 patients) did not describe how the suspicion was made and one study (45 patients) used multiple tests. Anxiety was diagnosed in collaboration with a psychologist in 2 studies (161 patients), by a psychiatrist in another 2 studies (102 patients), and by the rest of specialists—including dentists, dermatologists, and/or oral medicine/pathologists—in 27 studies (3,073 patients).

Twenty-four studies (3,450 patients) reported data on the prevalence of stress in OLP patients. Regarding the prevalence by continents, 9 studies (527 patients) took place in Asia, another 9 (1,691 patients) in Europe, 2 (768 patients) in North America, further 2 (30 patients) in South America, and two multicentric across various continents. Moreover, prevalence by stress suspicion method was also performed: 5 studies (163 patients) by DASS-21 test, 4 (558 patients) by anamnesis, 2 (302 patients) by Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) and Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ), HADS, General Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ), and Test of Recent Experience were used in one study (112, 49, 49 and 9 patients) respectively. Stress was diagnosed in collaboration with a psychologist in 2 studies (161 patients) and by the rest of specialists—including dentists, dermatologists, and/or oral medicine/pathologists—in 22 studies (3,289 patients).

Qualitative analysis

According to our risk of bias (RoB) analysis, all the studies were not conducted with the same scrupulousness, being the items Q2, Q9, and Q10, and those with the highest risk of bias (Fig. 2). The Q2 item investigates whether the studies recruited patients adequately, not reporting most of them random sampling methods from the study population. The Q9 item targets biases due to the lack of control of potentially confounding factors in the studies (design, measurement, and/or communication). The Q10 item assesses whether the relevant data from the study subpopulations (sex, age, alcohol and tobacco consumption) were reported appropriately.

Quality plot graphically representing the risk of bias in individual studies, critically appraising ten domains, using a method specifically designed for systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence (developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute, University of Adelaide, South Australia). Green, low risk of potential bias; yellow, moderate; red, high

Quantitative analysis (meta-analysis)

The results of the meta-analyses were graphically depicted in forest plots (Fig. 3, Appendix) and detailed in Table 2.

Depression

Prevalence of depression in OLP patients

The pooled proportion (PP) was 31.19% (95% CI = 22.27–40.82), with a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 97.14%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Magnitude of association between depression and OLP

Patients with OLP showed a significantly higher frequency of depression than the general population control group (OR = 6.15, 95% CI = 2.72–13.89, p < 0.001; Appendix p. 9).

Subgroup meta-analyses and meta-regressions

In the stratified analyses (Appendix pp. 10–14), we found significant differences between continents (p < 0.001), finding the highest prevalence in South America (PP = 55.58%, 95% CI = 47.20–63.81) and Asia (PP = 43.35%, 95% CI = 22.91–64.97). We also observed significant results between the tests used to diagnose depression. After adjustment in a multivariable meta-regression model, only anxiety maintained the statistical significance (p = 0.02), probably being the most influential covariate associated with the OLP depression comorbidity (Table 2; Fig. 4).

Bubble plot graphically representing the potential effect of the covariate anxiety (expressed as the percentage of patients with signs of anxiety, in x-axis) on the prevalence of depression among OLP patients (expressed as proportions, in y-axis). The fitted meta-regression line (red line) was depicted with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (black area), together with bubbles (grey circles) representing the estimates from primary-level studies (sized according to the precision of each estimate, the inverse of its within-study variance, in a z-axis)

Anxiety

Prevalence of anxiety in OLP patients

The estimated PP was 54.76% (95% CI = 42.06–67.17), with a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 98.00%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Magnitude of association between anxiety and OLP

Patients with OLP showed a significantly higher frequency of anxiety than the general population control group (OR = 3.51, 95% CI = 2.10–5.85, p < 0.001; Appendix p. 25).

Subgroup meta-analyses and meta-regressions

In the subgroup analyses (Appendix pp. 26–30), we found significant differences between continents (p < 0.001); South America outnumbered the rest of continents with the highest prevalence (PP = 99.88%, 95% CI = 95.71–100.00). Moreover, significant differences were observed between the tests used to diagnose anxiety. The prevalence did not vary significantly for the rest of the factors investigated (age, sex, tobacco and alcohol consumption) in the univariate meta-regression analyses (Appendix pp. 31–38) except for HDI (p = 0.03) (Table 3).

Stress

Prevalence of stress in OLP patients

The PP was 41.10% (95% CI = 32.18–50.32), with a significant degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 96.11%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Magnitude of association between stress and OLP

Patients with OLP showed a significantly higher frequency of anxiety than the general population control group (OR = 3.64, 95% CI = 1.48–8.94, p = 0.005; Appendix p. 39).

Subgroup meta-analyses and meta-regressions

In the stratified analyses (Appendix pp. 40–44), we found significant differences between continents (p < 0.001), finding the highest prevalence in South America. Prevalence did not vary significantly for the rest of the factors investigated (age, sex, tobacco, alcohol, and HDI) in the univariate meta-regression analyses (Appendix pp. 45–52) (Table 4).

Quantitative evaluation (secondary analyses)

Sensitivity analysis

The consecutive repetition of meta-analyses using the “leave-one-out” method (Appendix, pp. 56–61) did not vary the overall results considerably. Hence, the reported pooled estimations are not influenced by a specific primary-level study.

Analysis of small‐study effects

Egger’s regression test indicated statistically significant asymmetry for the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress in OLP patients (pEgger = 0.09, 0.01, and 0.02, respectively). Funnel plots (Appendix pp. 53–55) appeared to be slightly asymmetric for the studies plotted at the bottom, singularly for anxiety variable; however, due to a considerable degree of inter-study heterogeneity, the visual inspection analysis was complex. Nevertheless, the nonparametric trim and fill method did not detect the presence of unpublished studies, so the final estimates were not adjusted based on imputation techniques for missing studies. In summary, the presence of small-study effects was suspected, but publication bias was potentially ruled out.

Validation of methodological quality

The methods applied in this systematic review and meta-analysis were implemented, critically appraised, and validated using AMSTAR2 [39], obtaining an overall rating of “high” (15 out of 16 points) (the checklist, explanation, and scoring table are included in the Appendix, pp. 62–66).

Discussion

The results of our systematic review and meta-analysis show a strong association between OLP and psychological disorders, i.e., depression, anxiety, and stress. Patients with OLP present a risk of suffering from depression (p < 0.001), anxiety (p < 0.001), and stress (p < 0.005) significantly higher than the general population, with a prevalence of depression of 31.19%, anxiety of 54.76%, and stress of 41.10% among OLP patients. Our results were derived from the analysis of 51 studies that collected information from 6,815 patients with OLP. A meta-analysis on the subject that included patients with OLP [12] has recently been published, reporting a prevalence of depression and anxiety of 26% and 27% of the cases, respectively. It must be noted that this meta-analysis [12] presents critically low methodological quality, according to AMSTAR2, which is essentially due to a significant selection bias derived from having designed a low-sensitive search strategy that only identified 16 studies for analysis—a number of studies considerably lower than the 51 studies included in our present meta-analysis. Therefore, the results of Jalenque et al. [12] seem incomplete.

Our results also interestingly reveal that the studies reporting the higher prevalences of depression also report the higher frequencies of anxiety (p = 0.001), which seems to indicate a comorbidity among depression, anxiety, and OLP. Specialists involved in the diagnosis and treatment of OLP, especially dentists—as they are in the first line of care for patients with oral diseases—must be aware of these important comorbidities in order to implement appropriate measures that allow patients with OLP to receive the specialized care required for these emotional disorders. As previously mentioned, it may not be straightforward for a dentist to bring out psychological disorders in patients with OLP, whose main reason for consultation is the presence of oral mucosal lesions. In the experience of the authors (MAGM, SW), patients often do not disclose these conditions out of shame, feelings of stigmatization or fear of family incomprehension, and the adverse effects of psychotropic drugs. Occasionally, patients consider their emotional disorders as non-pathological situations derived from stress or everyday problems in life. Finally, sometimes dentists may not feel themselves authorized or trained to identify and refer patients to a psychiatrist or psychologist. The treatment of psychological disorders is a relevant issue since many of them considerably decrease the quality of life of the patient, which in itself can be notably deteriorated by OLP. Furthermore, although there is no scientific evidence on the subject, hypothetically, in some patients, the control of psychological disorders could also improve the OLP control, since it is frequent to note the worsening of OLP symptoms in periods in which the emotional symptoms increase. The training and insight of the dentist will make it possible to suspect the presence of emotional factors, and through an anamnesis carried out with subtlety, the patient will recognize the existence of these abnormalities.

According to our qualitative evaluation using a specific critical appraisal checklist designed by the Joanna Briggs Institute for systematic reviews addressing prevalence questions, although our included primary-level studies had similar study design, all were not conducted with the same rigor. Most potential biases were caused by the failure considering three specific items (i.e., Q2, Q9, and Q10). To meet Q2, future studies should recruit study participants in an appropriate way, always reporting how sampling was performed, and preferably using random sampling methods. On the other hand, Q9 and Q10, respectively, target biases due to potentially confounding factors and non-identified subpopulations, both items sharing similarities. Future studies should be better designed, correctly measuring and clearly reporting data related to age, sex, OLP type and location of lesions, medical history, and tobacco/alcohol habits. Furthermore, studies do not report treatment for these conditions or if OLP patient relapses are precipitated by worsening of the emotional status of patients. On the other hand, future studies should also focus on these issues. On the other hand, we tested the influence of risk of bias on the overall results using meta-regression, and no significant differences were observed. The overall results do not depend on the influence of the subset of studies with lowest quality, increasing the quality of evidence of the results reported in our meta-analysis. We strongly encourage future studies assessing the prevalence of psychological disorders in OLP, to consider the recommendations given in this systematic review and meta-analysis to improve and standardize future research (Table 5).

Our systematic review and meta-analysis also presents some limitations that should be discussed. First, an inherent limitation of the included studies, as previously commented, was the lack of reporting of relevant datasets that limited the number of observations in secondary analyses (e.g., influence of sex, age, alcohol, tobacco, etc.). Future studies should report datasets in a more rigorous way—preferably individual patient data—given the clinical and methodological relevance of these variables. Second, we observed considerable inter-study heterogeneity. As stated in our study protocol, it was expected, and planned random-effects models were applied in all meta-analyses to account for heterogeneity. In addition, we conducted several stratified meta-analyses by selecting more homogeneous subgroups, identifying that factors such as geographic areas, specific questionnaires, and the participation of a psychologist or psychiatrist to reach mental disorders’ diagnosis constitute important explanatory sources of heterogeneity. Finally, we performed random-effects meta-regression analyses and applied the REML method to produce an adjusted R2 statistic, which estimates the proportion of the inter-study variance explained by covariates. This analysis showed that anxiety is a very relevant source of heterogeneity (approximately explaining 75.25% of heterogeneity), significantly associated with an increased prevalence of depression among OLP patients. Despite the above limitations, the robust nature of our systematic review and meta-analysis is remarkable, as evidenced by our careful process of identification and selection of studies (see flow diagram), where more than 10,000 registers were screened and more than 1,500 papers subject to full-text reading; the absence of restrictions by publication language or date limits; robust qualitative recommendations for future studies on this topic; and potential translational opportunities derived from our comprehensive statistical analysis.

In conclusion, OLP patients suffer depression, anxiety, and stress more frequently than the general population. The physicians involved in the management of OLP, especially dentists, should be aware of these comorbidities in order to implement the appropriate measures for their referral.

Change history

13 August 2022

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

References

González-Moles MÁ, Ramos-García P, Warnakulasuriya S (2020) An appraisal of highest quality studies reporting malignant transformation of oral lichen planus based on a systematic review. Oral Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13741

González-Moles MÁ, Warnakulasuriya S, González-Ruiz I et al (2020) Worldwide prevalence of oral lichen planus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13323

Warnakulasuriya S, Kujan O, Aguirre-Urizar JM et al (2020) Oral potentially malignant disorders: a consensus report from an international seminar on nomenclature and classification, convened by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer. Oral Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13704

Ramos-García P, Ángel González-Moles M, Warnakulasuriya S (2021) Oral cancer development in lichen planus and related conditions -3.0 evidence level-: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Oral Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13812

González-Moles MÁ, Ruiz-Ávila I, González-Ruiz L et al (2019) Malignant transformation risk of oral lichen planus: a systematic review and comprehensive meta-analysis. Oral Oncol 96:121–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.07.012

Hampf BG, Malmström MJ, Aalberg VA et al (1987) Psychiatric disturbance in patients with oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 63:429–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(87)90254-4

Kövesi G, Bánóczy J (1973) Follow-up studies in oral lichen planus. Int J Oral Surg 2:13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0300-9785(73)80012-2

Rojo-Moreno JL, Bagán JV, Rojo-Moreno J et al (1998) Psychologic factors and oral lichen planus. A psychometric evaluation of 100 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 86:687–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90205-0

Chaudhary S (2004) Psychosocial stressors in oral lichen planus. Aust Dent J 49:192–195

Lundqvist EN, Wahlin YB, Bergdahl M, Bergdahl J (2006) Psychological health in patients with genital and oral erosive lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 20:661–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01559.x

Cerqueira JDM, Moura JR, Arsati F, et al (2018) Psychological disorders and oral lichen planus: a systematic review. J Investig Clin Dent 9:e12363. https://doi.org/10.1111/jicd.12363

Jalenques I, Lauron S, Almon S, et al (2020) Prevalence and odds of signs of depression and anxiety in patients with lichen planus: systematic review and meta-analyses. Acta Derm Venereol 100:adv00330. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-3660

Ramos-Garcia P, Roca-Rodriguez MDM, Aguilar-Diosdado M, Gonzalez-Moles MA (2021) Diabetes mellitus and oral cancer/oral potentially malignant disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis 27:404–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13289

Petti S, Rabiei M, De Luca M, Scully C (2011) The magnitude of the association between hepatitis C virus infection and oral lichen planus: meta-analysis and case control study. Odontology 99:168–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-011-0008-3

Lodi G, Pellicano R, Carrozzo M (2010) Hepatitis C virus infection and lichen planus: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Oral Dis 16:601–612. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01670.x

Li D, Li J, Li C et al (2017) The association of thyroid disease and oral lichen planus: a literature review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 8:310. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00310

Miyagaki T, Sugaya M, Miyamoto A, et al (2011) Oral erosive lichen planus associated with thymoma treated with etretinate. Australas J Dermatol 54:e25–e27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-0960.2011.00818.x

Higgins JP, Green S (2008) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series. In: Cochrane Handb. Syst. Rev. Interv. Cochrane B. Ser.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al (2017) AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ J 4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC et al (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. J Am Med Assoc 283:2008–2012. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 350:g7647

Aromataris E MZ (2020) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI

Agresti A, Coull BA (1998) Approximate is better than “exact” for interval estimation of binomial proportions. Am Stat 52:119–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.1998.10480550

Freeman M, Tuckey J (1950) Transformations Related to the Angular and the Square Root. Ann Math Stat 21:607–611. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177729756

DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7:177–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 21:1539–1558. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327:557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

Borenstein M, Higgins JPT (2013) Meta-analysis and subgroups. Prev Sci 14:134–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0377-7

Thompson SG, Higgins JPT (2002) How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med 21:1559–1573. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1187

Thompson SG, Sharp SJ (1999) Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Stat Med 18:2693–2708. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19991030)18:20%3c2693::aid-sim235%3e3.0.co;2-v

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG (2004) Controlling the risk of spurious findings from meta-regression. Stat Med 23:1663–1682. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1752

Viechtbauer W, Cheung MW-L (2010) Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 1:112–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.11

Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al (2011) Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 343:d4002

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315:629–634

Duval S, Tweedie R (2000) A non-parametric “trim and fill” method of assessing publication bias in meta-analysis. J Am Stat Assoc 95:89–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2000.10473905

Kalkur C, Sattur AP, Guttal KS (2015) Role of depression, anxiety and stress in patients with oral lichen planus: a pilot study. Indian J Dermatol 60:445–449. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5154.159625

Birckel E, Lipsker D, Cribier B (2020) Efficacy of photopheresis in the treatment of erosive lichen planus: a retrospective study. Ann Dermatol Venereol 147:86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annder.2019.02.011

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G et al (2017) AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 358:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Granada / CBUA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This is a systematic review and no ethical approval was required.

Informed consent.

This is a systematic review and no informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

De Porras-Carrique, T., González-Moles, M.Á., Warnakulasuriya, S. et al. Depression, anxiety, and stress in oral lichen planus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Invest 26, 1391–1408 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-021-04114-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-021-04114-0