Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to examine different central bearing point methods in patients with and without temporomandibular disorders (TMD) by an experienced and unexperienced examiner.

Material and methods

The 20 fully dentulous subjects were screened for TMD based on the Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD and distinguished into functional impaired and functional healthy groups. The mandibular relationship was recorded by an electronic central bearing tracing device (IPR-System, IPR GmbH, Oldenburg, Germany) with an integrated pressure sensor. Three bite registration methods were performed using this device: initial neuromuscular position, final neuromuscular position after dynamic sequences with the intraoral pin (=neuromuscular deprogramming), and centric relation guided manually by an experienced and an unexperienced examiner.

Results

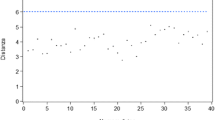

The neuromuscular positions before and after neuromuscular deprogramming were not significantly different (paired t test as a group comparison test: transverse: p = 0.369; sagittal: p = 0.486). Both positions were significantly anterior in comparison to the manually guided centric relation (paired t test as a group comparison test: p < 0.0001). The neuromuscular positions before and after deprogramming tend to have high scattering values.

Conclusion

By means of the central bearing point method, the manually guided centric relation is the one which is sufficiently reproducible. It seems doubtful to take the significant anterior neuromuscular position for a definite reconstruction.

Clinical relevance

Using the central bearing point method, the manually guided centric relation should be preferred, whereas the neuromuscular position should not be used for definite reconstructions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ash MM, JR (1995) Philosophy of occlusion: past and present. Dent Clin N Am 39:233–255

Hanau RL (1929) Occlusal changes in centric relation. J Am Dent Assoc 16:1903–1911

Linsen SS, Stark H, Samai A (2012) The influence of different registration techniques on condyle displacement and electromyographic activity in stomatognathically healthy subjects: a prospective study. J Prosthet Dent 107:47–54

Shafagh I, Amirloo R (1979) Replicability of chinpoint-guidance and anterior programmer for recording centric relation. J Prosthet Dent 42:402–404

Gysi A (1910) The problem of articulation. Dental Cosmos 52:1–19

Wood GN (1988) Centric relation and the treatment position in rehabilitation occlusions: a physiologic approach. Part 2: the treatment position. J Prosthet Dent 60:15–18

Denen HE (1938) Movements and positional relations of the mandible. J Am Dent Assoc 25:548–556

Lucia VO (1960) Centric relation—theory and practice. J Prosthet Dent 10:849–856

Boos R (1959) Centric relation and functional areas. J Prosthet Dent 9:191–196

Helkimo M, Ingervall B, Carlsson G (1971) Variation of retruded and muscular position of mandible under different recording conditions. Acta Odontol Scand 29:423–437

Trage R (1977) Untersuchung zur position des unterkiefers beim vollbezahnten. Dtsch Zahnärztl Z 32:108–110

Linsen SS, Stark H, Klitzschmüller M (2013) Reproducibility of condyle position and influence of splint therapy on different registration techniques in asymptomatic volunteers. Cranio 31:32–39

Remien J, Ash M (1974) Myo-monitor centric: an evaluation. J Prosthet Dent 31:137–145

Azarbal M (1977) Comparison of Myo-monitor centric position to centric relation and centric occlusion. J Prosthet Dent 38:331–337

Rieder CE (1978) The prevalence and magnitude of mandibular displacement in a survey population. J Prosthet Dent 39:324–329

Weffort SY, de Fantini SM (2010) Condylar displacement between centric relation and maximum intercuspidation in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. Angle Orthod 80:835–842

Abraham AP, Veeravalli PT (2012) A positional analyzer for measuring centric slide. J Indian Prosthodont Soc 12:216–221

Hellmann D, Becker D, Giannakopoulos NN, Eberhard L, Fingerhut C, Rammelsberg P, Schindler H (2014) Precision of jaw-closing movements for different jaw gaps. Eur J Oral Sci 122:49–56

Hupfauf L (1971) Vergleichende untersuchungen verschiedener registrierverfahren. Dtsch Zahnärtzl Z 26:158–162

Woda A, Pionchon P, Palla S (2001) Regulation of mandibular postures: mechanisms and clinical implication. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 12:166–178

Kinderknecht KE, Wong GK, Billy EJ, Li SH (1992) The effect of a deprogrammer on the position of the terminal transverse horizontal axis of the mandible. J Prosthet Dent 68:123–131

Piehslinger E, Celar A, Celar R, Jaeger W, Slavicek R (1993) Reproducibility of the condylar reference position. Journal of Orofacial Pain 7:68

Celenza FV (1973) The centric position: replacement and character. J Prosthet Dent 30:591–598

Utz K-H, Müller F, Lückerath W, Fuß E, Koeck B (2002) Accuracy of check-bite registration and centric condylar position. J Oral Rehabil 29:458–466

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Jonas (Denal laboratory Bernau, Germany) for the construction of the intraoral templates of the central bearing system and to deliver us the OrthaS®-Chair.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards (Ethical approval number: (EA4/025/09)).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

The author 2 received research grants from Company: IPR-Systeme GmbH, Bremer Heerstr. 291, 26135 Oldenburg (grant number: 20090299).

Informed consent

All participants gave their informed consents.

Additional information

Posterpresentations at the annual German Dentist Day (2010) and at the meeting of the Society of Oral Physiology (Store Kro, 2013).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zorn, A., Peroz, I. Electronic central bearing point as registration method in individuals with and without temporomandibular disorders. Clin Oral Invest 20, 2421–2427 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-016-1735-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-016-1735-1