Abstract

Recent advances in variable-resolution (VR) global models provide the tools necessary to investigate local and global impacts of land cover by embedding a high-resolution grid over areas of interest in a seamless and computationally efficient manner. We used two eddy covariance tower clusters in the Eastern USA to evaluate surface energy fluxes (latent heat, λE; sensible heat, H; net radiation, Rn; and ground heat, G) and surface properties (aerodynamic resistance to heat transfer, raero; Bowen ratio, β; and albedo, α) by uncoupled point simulations of the land-only Community Land Model (PTCLM4.5) and two coupled land–atmosphere Community Earth System Model (CESM1.3) simulations. The CESM simulations included a 1° uniform grid global simulation and global 1° simulation with a 0.25° refined VR grid over the Eastern USA. Tower clusters included the following plant functional types—broadleaf deciduous temperate (hardwood) forest, C3 non-Arctic grass (grass), a cropland, and needleleaf evergreen temperate (pine) forest. During the growing season, diurnal cycles of λE and H for grass and the cropland were simulated well by PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3; however, λE (H) was biased low (high) at the hardwood and pine forested sites, contributing to biases in β. Growing season Rn was generally well simulated by CLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3; however, modeled elevated albedo (indicative of snow cover) persisted longer in winter and spring leading to large biases in Rn and α. The introduction of a VR grid does not adversely impact surface energy fluxes compared to 1° uniform grids and highlights the usefulness of this approach for future efforts to predict land–atmosphere fluxes across heterogeneous landscapes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The need to accurately represent fluxes of energy between the land surface and atmosphere is a crucial part of predicting weather (Viterbo and Beljaars 1995; Koster et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2012) and climate (Dirmeyer et al. 2012; Lorenz et al. 2012; Cheruy et al. 2014). From a biophysical perspective, the vegetation type and soil moisture state strongly control land–atmosphere energy exchange and are capable of altering the boundary layer growth and structure (Weaver et al. 2002; Baidya Roy 2003; Findell and Eltahir 2003; Adegoke et al. 2007; Courault et al. 2007; Davin and Noblet-Ducoudré 2010; Garcia-Carreras et al. 2010; Dirmeyer et al. 2014), the timing and intensity of convection (Juang et al. 2007b; Findell et al. 2011; Taylor et al. 2012; Collow et al. 2014; Tawfik et al. 2015), and surface air temperature (Juang et al. 2007a; Lee et al. 2011; Luyssaert et al. 2014). Land cover is also an important control on the severity of extreme events such as heat waves (Seneviratne et al. 2006; Fischer et al. 2007; Teuling et al. 2010; Hirschi et al. 2011; Miralles et al. 2014) and droughts (Dirmeyer 1994; Myoung and Nielsen-Gammon 2010; Santanello and Peters-Lidard 2013; Teuling et al. 2013). While it is vital for land surface models to return observed surface fluxes across various climate zones and vegetation types, it is necessary to capture these surface fluxes in coupled land–atmosphere models in order to fully capture the effects of land cover on climate.

Land cover plays an important role in regulating climate through biophysical differences in albedo, Bowen ratio, and aerodynamic roughness (Bonan 2008; Davin et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2011; Luyssaert et al. 2014; Zhao and Jackson 2014; Bright et al. 2017). Previous studies have demonstrated that the temperate mid-latitudes region is characterized by complex responses to land use and land cover change. The complexity is due to the contrasting effects of radiative (albedo) and nonradiative processes (Bowen ratio, aerodynamic roughness) that can be of opposite sign and equal in magnitude, as demonstrated in both modeling and observational studies (Bonan 2008; Davin et al. 2007; Wickham et al. 2013; Zhao and Jackson 2014). A recent intermodel benchmarking comparison project has shown that most land surface models (LSMs) have difficulty capturing observed sensible heat flux, oftentimes being outperformed by a single variable linear regression model that uses incoming shortwave radiation as its only input (Best et al. 2015). This suggests that some valuable input information may be muted by LSMs when calculating sensible heat flux using processed-based modeling approaches. Latent heat flux was found to have similar deficiencies across models, consistently being outperformed by a three-variable linear regression model (Best et al. 2015).

While offline simulations provide an excellent test bed for evaluation, ultimately LSMs must be coupled to broader Earth system models (ESMs) to evaluate the influence of land cover on surface temperature (Pitman et al. 2009; Davin et al. 2007; Davin and Noblet-Ducoudré 2010; Lawrence and Chase 2010; Boisier et al. 2012, among others) and broader climate responses to land use and land cover change (LULCC). The Land-Use and Climate, IDentification of robust impacts (LUCID) project compared the climate response across multiple ESMs and found that the temperate mid-latitudes emerged as a region with diverging signals in responses to LULCC (Pitman et al. 2009; de Noblet-Ducoudré et al. 2012). One of the key reasons the models diverged was the parameterization of processes simulating evapotranspiration and the representation of key surface properties that vary with LULCC like albedo (Pitman et al. 2009). Several modeling studies have also focused on more targeted and idealized land cover change experiments such as deforestation over the Amazon (Shukla et al. 1990; Dickinson and Kennedy 1992) or cropland expansion (Feddema et al. 2005; Diffenbaugh 2009). Using the Weather and Research Forecast Model (WRF), Collow et al. (2014) showed that the complete removal of vegetation over the Southern Great Plains produced significantly less precipitation compared to natural vegetation. An additional modeling experiment was performed by Collow et al. (2014) where soil moisture was uniformly increased. They found that the drying caused by vegetation removal produced a greater precipitation response than the uniform addition of soil moisture. This is similar to an earlier work by Blyth et al. (1994) who found a 30% increase in precipitation over France when comparing a completely forested landscape to bare ground. However, the question still remains as to whether the fluxes from the models themselves are reliable enough to accurately address these land cover change questions. It is therefore important to understand how representation of surface properties and parameterization of surface fluxes in ESMs compare to surface observations.

While ESMs have progressively moved from coarser (~ 2.5°) to finer resolution (~ 1°), the computational cost to capture regional details in topography and land cover precludes the practice of running global simulations at ~ 0.25°. The recently developed variable-resolution Community Earth System Model (VR-CESM1.3) provides the framework to run global coupled land–atmosphere simulations with defined regions at higher spatial resolution at a fraction of the computational cost of globally uniform high-resolution grids (Zarzycki et al. 2014, 2015). In the Sierra Nevada, increased spatial resolution from 1° to 0.25° improved representation of snow dynamics and surface climate (Huang et al. 2016; Rhoades et al. 2016).

Here we evaluate surface energy fluxes and surface properties from the uncoupled Community Land Model (CLM4.5; Oleson et al. 2013) in single-point mode (PTCLM4.5) and the coupled VR-CESM1.3 against measurements from two closely spaced eddy covariance flux tower clusters in the Eastern USA. The tower clusters include four plant functional types (PFTs) common to the region: (1) needleleaf evergreen temperate (NET) forest, broadleaf deciduous temperate (BDT) forest, C3 non-Arctic grass (C3NAG), and rain-fed crop (CRO; e.g., corn). The goal of this evaluation is to determine the fidelity of CLM4.5 in capturing the observed flux climatology across PFTs under observationally forced conditions (PTCLM4.5) and a freely interacting land–atmosphere simulation (VR-CESM1.3). This evaluation is unique in that PFT-level output is evaluated from the VR-CESM1.3 simulations rather than the standard grid cell level comparisons used in validating coupled model simulations, which calculate a weighted average across multiple PFTs (Dirmeyer et al. 2006; Lorenz et al. 2012). For this reason and others, subgrid data reporting has been added as a key component in the Land Use Model Intercomparison Project (LUMIP; Lawrence et al. 2016). The PFT-level evaluation approach provides a more direct assessment with respect to observations because the modeled fluxes and surface properties corresponding to a particular land cover type, instead of a weighted grid cell average of several PFTs, can be directly compared to measurements.

With this evaluation, our goal is to answer the following questions: Does land cover type affect the ability of CLM4.5 to capture observed flux climatology? Do these results change if the model is forced with observations or driven with a freely interacting land–atmosphere simulation? Answering these questions will key opportunities to improve parameterization of CLM4.5 and other similar models, and will open the path to using variable-resolution models for land cover and land use studies.

2 Methods

2.1 Eddy covariance flux tower sites

2.1.1 University of New Hampshire (UNH), Durham, New Hampshire

The tower cluster in Durham, New Hampshire was installed in 2014 and includes three eddy covariance flux towers that collect data over a cornfield (UNH-crop), a hayfield consisting of C3 non-Arctic grass (UNH-grass), and a broadleaf deciduous temperate forest (UNH-hardwood) (Fig. 1). The sampling period included uninterrupted snow cover from January 2015 through late March 2015 at all three sites, with snow cover persisting through early April 2015 at the UNH-hardwood site.

The towers sampled meteorological and near-surface eddy covariance fluxes at half-hourly intervals (Table 1). Turbulent sensible (H) and latent heat (λE) fluxes were measured using a LI-COR® LI-7200 enclosed path CO2/H2O analyzer and Gill® Windmaster sonic anemometer at 1 m above the cornfield and hayfield canopies and 5 m above the forest canopy. Turbulent fluxes were calculated using the EddyPro® open source software (EddyPro®, 2014). Radiative fluxes were measured using Kipp & Zonen CNR4 net radiometers that measure incoming and outgoing longwave and shortwave radiation at each tower.

Gap filling for missing meteorological data (air temperature, incoming shortwave, precipitation, relative humidity, and wind speed) in the flux tower cluster was performed using two United States Climate Reference Network (USCRN) stations that provide subhourly meteorological data, available from 2002 to present. The USCRN Durham 2N station is located 400 m west of the UNH-grass tower; the USCRN Durham 2SSW is located in a hayfield 400 m east of the UNH-hardwood tower (Fig. 1). Meteorological data from the Durham 2N station were used to fill missing meteorological data in the UNH-grass tower and the UNH-crop tower. Missing data from the UNH-hardwood tower was filled using meteorological data from the Durham 2SSW tower. Any remaining missing data in the flux tower record (< 0.01% of the half-hourly data) were filled using linear interpolation. Filled meteorological variables include air temperature (Ta), relative humidity (RH), precipitation (PRCP), incoming shortwave radiation (SWin), and wind speed (WS). Missing pressure data in the flux towers were filled using the National Weather Service Automatic Surface Observing System (NWS/ASOS) data collected at Portsmouth International Airport at Pease in Portsmouth, NH (PSM). The amount of missing data gap-filled with USCRN data varied by site and by variable. At a maximum, no more than 26% of meteorological data were gap-filled at UNH-grass, less than 20% at UNH-corn, and less than 5% at UNH-hardwood.

2.1.2 Duke Forest, Durham, North Carolina

The Duke Forest tower cluster includes three ecosystems: an open pasture (Duke-grass), a hardwood forest (Duke-hardwood), and a loblolly pine forest (Duke-pine) (Fig. 1). Meteorological and surface energy flux data analyzed here were collected between 2004 and 2008. Details on data processing and quality control of the Duke Forest tower sites are described in Novick et al. (2009, 2015). Briefly, turbulent fluxes were measured using eddy covariance systems composed of a CSAT3 sonic anemometer (Campbell Scientific, Logan, UT, USA) and an open-path gas analyzer (LI-7500, Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA). Incoming and outgoing short- and longwave radiation were measured with Kipp & Zonen CNR4 net radiometers (Kipp & Zonen, Delft, the Netherlands). Wind and scalar concentration measurements were collected at 10 Hz, and fluxes were processed in real time. The Webb–Pearman–Leuning correction (Webb et al. 1980) for air density fluctuations was applied to the half-hourly λE fluxes. The data were then screened to remove measurements collected during suboptimal meteorological conditions using the online eddy covariance processing tool (http://www.bgc-jena.mpg.de/~MDIwork/eddyproc), which employs the friction velocity filtering method of Reichstein et al. (2005). The footprint model of Hsieh et al. (2000), extended to two dimensions by Detto et al. (2006), was used to estimate the flux footprint for every half-hour averaging period, and data were removed when the footprint was not representative of the study ecosystem (see Novick et al. 2015 for details). Gapfilling of missing meteorological data at these sites is accomplished by parameterizing linear relationships between similar instruments located across the three sites, and then using these linear transformations to estimate missing observations when one of the sensors malfunctioned.

2.2 Model simulations

2.2.1 Community land model point simulations (PTCLM)

The Community Earth System Model (CESM; Hurrell et al. 2013) is a state-of-the-art global climate model jointly developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and the Department of Energy (DOE). The CESM consists of interactive components representing the land surface, atmosphere, ocean, and sea ice. The CLM (Lawrence et al. 2011; Oleson et al. 2013) is the land surface model of the CESM (Hurrell et al. 2013). It simulates the surface energy and water fluxes over vegetated, urban, glacier, lake, wetland, and bare ground land unit types. Vegetated lands are further subdivided into one of 16 PFTs, four of which are examined here: (1) BDT (UNH-hardwood and Duke-hardwood), (2) NET (Duke-pine), C3NAG (UNH-grass and Duke-grass), and a generic crop (UNH-crop).

The CLM version 4.5 (CLM4.5; Oleson et al. 2013) was run in offline point (PTCLM4.5) simulation mode with satellite phenology; explicit biogeochemistry was not simulated. In point mode, CLM4.5 is not coupled to other CESM model components (i.e., atmosphere, ocean, sea ice), and the entire point is a single PFT and, therefore, a single set of PFT-specific parameters (see Oleson et al. 2013). It simulates the biogeophysical exchange of surface energy and water forced with flux tower meteorology including precipitation, surface air temperature, wind speed, surface air pressure, and incoming shortwave and longwave radiation. PTCLM4.5 site characteristics, PFTs, and simulation periods are listed in Table 1. A 50-year spin-up using tower meteorology forcing was conducted for each site to allow soil moisture and soil temperature to reach equilibrium, and output produced at 1 h intervals.

2.2.2 Variable-resolution Community Earth System Model (VR-CESM)

Variable-resolution capabilities have been recently implemented in the CESM framework (VR-CESM1.3), allowing for regional refinement within a global grid (Zarzycki et al. 2014). VR-CESM has been shown to improve aspects of regional climate (e.g., tropical cyclones, snow cover extent) requiring high resolution without adversely impacting the mean global circulation (Zarzycki and Jablonowski 2014; Zarzycki et al. 2015; Rhoades et al. 2016). Here, we ran VR-CESM1.3 simulations using CLM4.5 coupled to the Community Atmosphere Model (CAM5.1; Neal et al. 2010). All model components use the same variable-resolution grid. The SSTs and sea ice were prescribed using historical observations following the Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project (AMIP; Gates 1992) protocols. Other than the surface constraints imposed by these forcings, the atmosphere and land models are allowed to evolve freely and develop balanced climatological states specific to the coupled system assessed here.

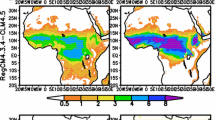

Two VR-CESM1.3 simulations were completed, one with a 1° uniform grid and a second with a 0.25° refined mesh over the USA within a 1° global grid (Fig. 2). Each CLM grid cell was subdivided into columns of land cover type (vegetated, urban, lake, and glacier), derived from the MODerate resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) data (Lawrence and Chase 2010). The vegetated column of the grid cell is further subdivided into at most four of 16 available vegetated PFTs. Four PFTs most common to the Eastern USA (BDT, NET, C3NAG, and CROP) are investigated here (Table 1).

At the column level, all PFTs within a CLM4.5 grid cell receive the same upper boundary fluxes (e.g., incoming shortwave radiation) from the lowest model level in the atmosphere produced in CAM5.1. After a 50-year CLM4.5 spin-up period to bring soil moisture and temperature to equilibrium, VR-CESM1.3 simulations were run from 1979 to 2008 with surface energy fluxes output at the PFT level every 3 h, providing high temporal resolution model output to compare against flux tower observations. Ideally, model simulations would be conducted to overlap in time with the flux tower measurements from the UNH cluster; however, AMIP forcing files were not available beyond 2008.

2.3 Comparison of flux towers and models

Diurnal cycles of surface energy fluxes from PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3 were evaluated against flux tower estimates of latent heat (λE), sensible heat (H), and net radiation (Rn). Flux tower estimates of daily albedo (α), Bowen ratio (β), and aerodynamic resistance to heat transfer (raero) were also used to assess performance of PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3. The following equations were used to calculate α, β, and raero:

where SWout is outgoing shortwave radiation, SWin is incoming shortwave radiation, ρ is the density of air (1.225 kg m−3), Cp is the specific heat of air (1004.5 J kg−1 K−1), Ts is the radiative skin temperature, and Ta is standard reference height air temperature. The radiative skin temperature Ts is calculated from outgoing longwave radiation:

where LWout is outgoing longwave radiation, ε is emissivity, and σ is the Stefan–Boltzman constant (5.67e−8 J m−2 s−1 K−4). Daily albedo values were calculated from Eq. 1. Growing season (June through August) β was calculated using daytime values only.

In addition to raero calculated using Eq. 3, CLM calculates aerodynamic resistance calculated explicitly using the Monin–Obukhov similarity theory for heat (rah) and momentum (ram):

where Va is the momentum gradient profile, u* is friction velocity, and θatm, θs, and θ* are potential temperature at 2-m reference height, surface, and scaled for instability, respectively (Oleson et al. 2013). The additional aerodynamic variables ram and rah were not included in the VR-CESM model output but were included for the PTCLM model output at hourly intervals. Due to energy balance requirements in PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3, the calculation of raero using Eq. 3 can lead to unrealistically high (≫ 500 s m−1) or negative values. Values of raero greater than 500 s m−1 and less than 0 s m−1 were therefore removed from the analysis. This resulted in removal of less than 10% of the VR-CESM raero values. The same limits were applied to flux tower calculations of raero and PTCLM calculations of rah and ram. Setting an upper limit for aerodynamic resistance terms allowed us to maintain consistency among towers, PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3.

For VR-CESM1.3 simulations, diurnal cycles of surface energy fluxes (λE, H, and Rn) and raero were averaged at the subgrid PFT level over the period 1979–2008. The 30-year averages were compared to the diurnal cycle obtained from the observational records available at the tower clusters listed in Table 1. Daily albedo was calculated using Eq. 1 and averaged by PFT for snow-covered (\( {\overline{\alpha}}_{\mathrm{SC}} \)), snow-free/dormant (\( {\overline{\alpha}}_{\mathrm{SF}} \)), and summer (June through August) growing season (\( {\overline{\alpha}}_{\mathrm{GS}} \)) periods. A vegetated land unit was considered snow-covered when all 3-h time steps within a given day had the fraction of snow cover (FSNO) equal to 1, and snow-free when all FSNO values in a given day were equal to 0. Because FSNO is a grid cell–level variable and the fractional snow cover is not calculated at the PFT level, days with FSNO between 0 and 1 were not included in the analysis.

3 Results

The overall performance of PTCLM4.5’s simulations of hourly surface energy fluxes (λE, H, Rn) is summarized in a Taylor diagram (Taylor 2001; Fig. 3). Taylor diagrams succinctly display the root-mean-square difference (RMSD), correlation coefficient (r), and normalized standard deviation of the simulations relative to the observed quantities. A perfect simulation would therefore plot closest to the gray dot on the x-axis along the radial direction in Fig. 3.

Taylor diagram (Taylor 2001) summarizing correlation coefficients (arc axis), centered root-mean-square difference (gray, dashed circles), and normalized standard deviations (y-axis) between PTCLM4.5 and flux tower observations of surface energy fluxes: latent heat (blue), sensible heat (red), and net radiation (black). Open symbols are UNH flux tower sites; closed symbols are Duke flux tower sites. Squares are grass, circles are hardwood forest, diamonds are pine forest, and triangles are crop. A perfect simulation would plot closest to the gray dot on the x-axis along the radial direction

Net radiation is simulated well by PTCLM4.5, with correlations exceeding 0.97, RMSDs less than 0.25, and normalized standard deviations 1 ± 0.06 at all flux tower sites. For λE and H, performance of PTCLM4.5 is stratified more so by cluster location than by PFT, though biases associated with instrumentation and data quality may confound this interpretation. The modeled PTCLM4.5 λE have higher correlations and RMSDs with observations at the Duke flux tower sites than the UNH sites. Likewise, modeled PTCLM4.5 H is more highly correlated with the Duke tower observations than H from the UNH sites, and the spread in normalized standard deviations is larger at the UNH sites.

The overall performance as indicated by the Taylor diagram (Fig. 3) is an important first step in understanding how well the coupled and uncoupled models simulate surface energy fluxes. However, the surface energy fluxes and surface properties relevant to LULCC signals vary on seasonal, monthly, and diurnal time scales not well represented in a Taylor diagram. In the next section, the uniform 1° CESM and 0.25° VR-CESM are compared to tower observations to evaluate the timing and magnitude of the diurnal cycle of λE, H, and Rn.

3.1 Coarse 1° CESM and 0.25° VR-CESM comparison with observed surface energy fluxes

When driven by the same AMIP forcing files, surface energy fluxes from the 1° uniform CESM simulations did not differ considerably from the 0.25° VR-CESM simulations at the UNH sites (Fig. 4) or the Duke sites (Fig. 5). At the UNH sites, summer latent heat fluxes (Fig. 4a–c), sensible heat flux (Fig. 4d–f), and net radiation (Fig. 4g–i) from the uniform 1° CESM and 0.25° VR-CESM are nearly indistinguishable. While both model simulations capture the diurnal magnitude observed in tower measurements at the UNH-grass site (Fig. 4a), the models tend to overestimate (underestimate) the magnitude of latent (sensible) heat flux and at UNH-crop and underestimate (overestimate) latent (sensible) heat at UNH-hardwood relative to tower observations (Fig. 4c). The differences between the coarse 1° uniform CESM and 0.25° VR-CESM surface energy fluxes were slightly larger at the Duke forested sites and generally within ± 30 W m−2 (Fig. 5). Both coupled CESM model simulations greatly overestimate sensible heat flux (+ 150 W m−2) at the Duke-hardwood site. A comparison of the coarse 1° uniform CESM and 0.25° VR-CESM wintertime surface energy fluxes can be found in the Electronic supplementary material (UNH: Fig. S1; Duke: Fig. S2).

Summer (June–August) surface energy fluxes from eddy covariance towers (black), 1° uniform CESM (red), and 0.25° VR-CESM (blue). Diurnal cycle shown in local time for latent heat (λE), sensible heat (H), and net radiation (Rn) at the UNH-grass (a, d, g), UNH-crop (b, e, h), and UNH-hardwood (c, f, i) sites. All fluxes in watts per square meter. Shading and error bars indicate ± 1σ

Summer (June–August) surface energy fluxes from eddy covariance towers (black), 1° uniform CESM (red), and 0.25° VR-CESM (blue). Diurnal cycle shown in local time for latent heat (λE), sensible heat (H), and net radiation (Rn) at the Duke-grass (a, d, g), Duke-hardwood (b, e, h), and Duke-pine (c, f, i) sites. All fluxes in watts per square meter. Shading and error bars indicate ± 1σ

The analysis comparing 1° uniform CESM and 0.25° VR-CESM demonstrates that that VR-CESM does not adversely impact simulation of mean climatology for latent heat diurnal patterns compared to the fixed resolution model; however, both models have challenges in accurately simulating the diurnal cycle in latent and sensible heat at forested sites. A more detailed analysis comparing the coupled VR-CESM simulations, the uncoupled PTCLM simulations, and tower observations follows in Section 3.2.

3.2 Uncoupled PTCLM vs. coupled VR-CESM modeled surface energy fluxes compared to tower observations

3.2.1 Diurnal cycle of latent heat flux (λE)

The VR-CESM modeled summer diurnal cycle of λE was in good agreement with observations from the UNH-grass site (Fig. 6a). Midday λE at the UNH-crop site was within the observed range of variability for both models, though the mean is biased high in PTCLM4.5 (+ 62 W m−2) and VR-CESM1.3 (+70 W m−2) (Fig. 6b). Conversely, λE at the UNH-hardwood forested site was biased low in both PTCLM4.5 (by − 130 W m−2) and VR-CESM1.3 (by − 140 W m−2) (Fig. 6c). For all PFTs in the UNH tower cluster, coupling to the atmosphere in VR-CESM1.3 had little impact on simulated summer latent heat flux compared to the uncoupled PTCLM4.5 simulations forced by tower meteorology.

a–l Summer diurnal cycle of latent heat flux (λE), sensible heat (H), net radiation (Rn), and ground heat flux (G) for C3 non-Arctic grass (UNH-grass; left column), crop (UNH-crop; middle column), and broadleaf deciduous temperate forest (UNH-hardwood; right column) at UNH. Hourly averaged fluxes shown for flux towers (black), PTCLM4.5 (red), and 3-hourly fluxes for VR-CESM (blue). Shading and error bars indicate ± 1σ. Tower and PTCLM4.5 values were averaged over the period 2014–2015. All VR-CESM values are averaged over the period 1979–2008

PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3 capture the summer diurnal cycle of λE very well at the Duke-grass site (Fig. 7a). At the Duke-hardwood site, daytime λE is biased low in the uncoupled PTCLM4.5 (− 75 W m−2) and the coupled VR-CESM1.3 (− 50 W m−2) simulations (Fig. 7b). The daytime λE simulated for the Duke-pine site is also biased low in PTCLM4.5 (− 55 W m−2), though the bias is reduced in the VR-CESM1.3 simulations to − 30 W m−2 (Fig. 7c).

a–l Summer diurnal cycle of latent heat flux (λE), sensible heat (H), net radiation (Rn), and ground heat flux (G) for C3 non-Arctic grass (Duke-grass; left column), broadleaf deciduous temperate forest (Duke-hardwood; middle column), and needleleaf evergreen temperate forest (Duke-pine; right column) at UNH. Hourly averaged fluxes shown for flux towers (black), PTCLM4.5 (red), and 3-hourly fluxes for VR-CESM (blue). Shading and error bars indicate ± 1σ. Tower and PTCLM4.5 values were averaged over the period 2014–2015. All VR-CESM simulations were averaged over the period 1979–2008

Because exposed leaf area index (LAI) exerts a first-order control on simulation of latent heat in CLM4.5, we compared measured LAI values for the Duke sites (Stoy et al. 2006) to PTCLM4.5 LAI values (Table 2). LAI ranges from under 1.5 to just under 4 m2 m−2 at Duke-grass, between 6 and 7 m2 m−2 at Duke-hardwood, and between 4 and 6 m2 m−2 at Duke-pine, with the lowest Duke-pine LAI measurements following ice storm damage sustained in December 2002. Model LAI was underestimated at the Duke-hardwood site and may contribute to the low daytime bias in modeled λE. In general, modeled LAI values were within the range of observed values at the Duke-pine and Duke-grass sites. The lower end of the range in LAI at the Duke-grass site is a dynamic response to hay harvesting, which occurs once or twice a year but not necessarily at the same time each year. LAI measurements were not available for the UNH tower sites.

3.2.2 Diurnal cycle of sensible heat flux

Summer H for UNH-crop was simulated reasonably well by PTCLM4.5 compared to tower estimates (Fig. 6e). When coupled to the atmosphere in VR-CESM, UNH-crop H was underestimated by − 25 W m−2. Coupling to the atmosphere had little effect on BDT and NET H, which was overestimated by + 100 W m−2 at UNH-hardwood forest (Fig. 6f), + 160 W m−2 at Duke-hardwood forest (Fig. 7e), and + 105 W m−2 at Duke-pine forest (Fig. 7f). For the Duke-grass site, PTCLM4.5 overestimated sensible heat flux by about + 45 W m−2, while VR-CESM1.3 underestimated sensible heat flux by + 37 W m−2 (Fig. 7d).

3.2.3 Diurnal cycle of net radiation

The diurnal cycle of summer net radiation was generally well captured by both PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3 compared to the flux tower observations at both the UNH (Fig. 6g–i) and Duke (Fig. 7g–i) sites. At the UNH BDT site, midday PTCLM4.5 Rn was biased low by − 40 W m−2 (Fig. 6f). The Duke-grass summer Rn was biased high at midday by 30 W m−2 (Fig. 7d). At all the other sites, summer Rn simulated by PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3 were within ± 20 W m−2 of flux tower estimates. Although Rn was very well captured in both models, the biases in H and λE resulted in a combined effect of compensating errors that are discussed later in the Bowen ratio section (Section 3.2.6).

In winter, PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3 midday Rn was biased low (− 60 to − 80 W m−2) relative to flux tower estimates at all three sites in Durham, NH (Fig. S3g–h). The low bias in PTCLM4.5 was related to the simulation of snow cover, discussed in more detail in the albedo section below (Section 3.2.5). The low bias in Rn and retention of snow cover in PTCLM4.5 resulted in a reduced sensible heat flux (Fig. S3d–f). With CLM4.5 coupled to the atmosphere in VR-CESM1.3, the bias in net radiation was alleviated (Fig. S3g–i). At the Duke sites, modeled winter net radiation does not appear to be affected by snow cover in the manner that affected the UNH tower sites (Fig. S4g–i).

3.2.4 Diurnal cycle of ground heat flux (G)

Measured ground heat fluxes at the Duke-grass (Fig. 5j) and Duke-DBT (Fig. 7k) were relatively small in summer, typically less than 20 and 8 W m−2, respectively, at midday and greater than − 7 and − 3 W m−2, respectively, at night. PTCLM4.5 simulated a much more pronounced diurnal cycle in G at the Duke-grass site, up to 100 W m−2 around local noon and − 35 W m−2 at night during the summer months. Modeled biases from the VR-CESM1.3 simulation of G were greater still at the Duke-grass site, but lower at the Duke-hardwood site. The UNH sites and the Duke-pine site did not have ground heat flux tower measurements available for comparison with PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3. Nonetheless, we can still evaluate differences in simulation of ground heat flux between PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3. In comparison to PTCLM4.5 forced by tower meteorology, coupling to the atmosphere in VR-CESM1.3 tended to increase G at the UNH open sites (Fig. 6j–k) and decreased G at the UNH-hardwood site (Fig. 6l) and Duke-pine site (Fig. 7l).

3.2.5 Daily and seasonal albedo

When forced with tower meteorology, PTCLM4.5 summertime albedo at the UNH-grass site was underestimated by 0.05, though generally well simulated during senescence and the dormant, snow-free season in late fall (Fig. 8a). When both the tower and PTCLM4.5 had snow cover, surface albedo was generally well captured at UNH-grass. However, albedo was greatly overpredicted in PTCLM4.5 when snow cover persisted longer during the spring melt season, as well as during a melt event that occurred between mid-December 2014 and late January 2015. The same pattern with respect to snow-covered albedo was apparent at the UNH-crop site (Fig. 8b). At the UNH-hardwood forest, summertime albedo was simulated well by PTCLM4.5, though overestimated in winter when PTCLM4.5 overestimated the albedo of the snow-covered canopy (Fig. 8c).

The annual cycle of albedo predicted by PTCLM4.5 was comparable to the flux tower measurements at the Duke-grass site (Fig. 9a). Snow cover in mid-February 2004 led to a spike in albedo in the Duke-grass flux tower albedo record that was not simulated by PTCLM4.5. Similarly, there were three occasions when PTCLM4.5 simulated snow cover at Duke-grass and subsequent increases in albedo that were not observed in the flux tower albedo record. At the Duke-hardwood site, the PTCLM4.5 annual cycle showed relatively constant albedo through the growing season, whereas the flux tower observations indicated a gradual decrease in albedo from the start of the growing season through senescence (Fig. 9b). Mid-winter albedo at the Duke-pine site was biased low by PTCLM4.5 and biased low (− 0.05) in spring and summer (Fig. 9c).

At the UNH-grass and Duke-grass sites, the climatological (1979–2008) mean snow-free, dormant (\( {\overline{\alpha}}_{\mathrm{SF}} \)) and growing season (\( {\overline{\alpha}}_{\mathrm{GS}} \)) albedo from VR-CESM1.3 did not differ significantly from PTCLM4.5, though both models underestimated \( {\overline{\alpha}}_{GS} \)relative to the flux tower estimates at UNH-grass (Fig. 10a) and Duke-grass (Fig. 8d).

Mean snow-covered albedo (\( {\overline{\alpha}}_{\mathrm{SC}} \)) was simulated well by PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3 at UNH-grass (Fig. 10a) and UNH-crop (Fig. 10c) but was biased high at UNH-hardwood (Fig. 10b). The Duke sites had too few occasions with deep (> 10 cm) snow cover to calculate meaningful statistics for \( {\overline{\alpha}}_{\mathrm{SC}} \).

3.2.6 Monthly and summer Bowen ratio (β)

The PTCLM4.5 simulated monthly average β derived from the daytime average H and λE was compared against observations from 2004 to 2008 at the Duke flux tower sites (Fig. 11). The observed β at Duke-grass was generally well captured by PTCLM4.5 from January 2004 through September 2005 (Fig. 11a). At the Duke-hardwood flux tower site, the mid-winter β peak was underpredicted by PTCLM4.5, while the summertime minimum in β was overestimated by PTCM4.5 (Fig. 11b). At the Duke-pine site, β tended to be biased high in PTCLM4.5, particularly in winter (Fig. 11c). At the UNH towers, winter snow cover frequently led to large negative β values when surface air temperature was warmer than the skin temperature of the snow and/or frozen ground and sensible heat flux was negative. As such, only mean summertime β values are presented (Table 3).

The climatological mean summertime β during the day was calculated for the VR-CESM1.3 simulations (1979–2008) and compared to summertime β at the flux tower sites and PTCLM4.5 simulations (Table 3). In general, modeled β at the forested sites was biased high relative to the flux tower estimates. PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM BDT β was nearly double the β calculated from the flux tower data at UNH-hardwood and Duke-hardwood sites. For the Duke-pine site, both PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3 overpredicted summertime β. At the Duke-grass flux tower site, β was simulated reasonably well by PTCLM4.5 when forced with tower meteorology, but was biased low in the VR-CESM1.3 coupled simulations. The UNH-crop tower had a low bias in modeled PTCLM4.5 summertime β that worsened in VR-CESM1.3. It is worth noting that 2007 was a severe drought year, and temporal shifts in the Bowen ratio at the Duke-hardwood (Fig. 11b) and Duke-pine (Fig. 11c) may be due to inadequate drought response in PTCLM.

3.2.7 Diurnal cycle of aerodynamic resistance to heat transfer (r aero, r ah, and r am)

The diurnal cycle of raero was evaluated to explore the ability of the uncoupled PTCLM4.5 and coupled VR-CESM1.3 to represent the efficacy of heat transfer to and from the atmosphere (see Eq. 3). The diurnal cycle of raero was calculated using Eq. 3 for the flux towers, PTCLM4.5, and VR-CESM1.3 during the summertime growing season (Fig. 12) and in winter (Fig. 13). In summer, PTCLM4.5 tended to overpredict raero at night, while VR-CESM1.3 had a tendency to underpredict raero. The largest nighttime bias in growing season raero occurred at the Duke-pine site (Fig. 12f). The underpredicted raero suggests that VR-CESM1.3 is more efficient at exchanging heat between CLM4.5 and CAM5.1 than the uncoupled PTCLM4.5 runs. This may be due to observational constraints placed on PTCLM4.5.

Summer diurnal cycle of aerodynamic resistance to heat transfer (ra), calculated using Eq. 3 for flux towers (black), PTCLM4.5 (red), and VR-CESM1.3 (cyan). Shaded regions show ± 1σ

a–f Winter (December–February) diurnal cycle of aerodynamic resistance to heat transfer (ra), calculated using Eq. 3 for flux towers (black), PTCLM4.5 (red), and VR-CESM1.3 (cyan). Shaded regions show ± 1σ

In winter, raero was overpredicted by PTCLM4.5 at all UNH flux tower sites (Fig. 13a–c). At both the UNH sites and the Duke sites, the diurnal cycle of raero was less pronounced in VR-CESM1.3 compared to PTCLM4.5 and tower estimates. The winter diurnal cycle of raero was simulated well by PTCLM4.5 at the Duke-grass site (Fig. 13d) and the Duke-hardwood site (Fig. 13e) but underpredicted by VR-CESM1.3 at night. For the Duke-pine site, PTCLM4.5 overestimated raero at night (Fig. 13f).

The PTCLM aerodynamic resistance terms explicitly using the Monin–Obukhov similarity theory for heat (rah) and momentum (ram) were also evaluated against the tower raero and PTCLM raero (Fig. 14). The UNH-grass site shows widespread agreement among tower raero and PTCLM raero, ram, and rah, while the Duke-grass site tends to have higher raero values compared to MO-derived rah and ram. At the UNH-hardwood and Duke-hardwood sites, the PTCLM aerodynamic resistance terms explicitly using the Monin–Obukhov similarity theory for heat (rah) and momentum (ram) tend to be higher at night compared to tower and PTCLM raero values calculated using Eq. 3. The Duke-pine ram and rah diurnal cycles are very similar, though morning raero values in PTCLM tend to be lower than PTCLM ram and rah.

Summer (June–August) diurnal cycle of aerodynamic resistance terms for UNH-grass (a–d), UNH-crop (e–h), UNH-hardwood (i–l), Duke-grass (m–p), Duke-hardwood (q–t), and Duke-pine (u–x). Tower (left-most column) and PTCLM (middle-left column) raero calculated using Eq. 3. PTCLM ram and rah calculated using Monin–Obukhov similarity theory (see Oleson et al. 2013)

4 Discussion

Land surface models are commonly used for assessing the climate impacts of land cover, but care must be taken to understand the limitations of the models. In the PTCLM4.5 simulations forced by tower meteorology, each PFT received slightly different forcing data. In coupled VR-CESM1.3 simulations, forcing data were provided by a freely evolving atmosphere at the grid cell level such that all PFTs contained within the same grid cell received the same atmospheric forcing. In this setup, PFT-level output from VR-CESM1.3 provides an ideal model configuration for understanding the influence of land cover on surface climate because it eliminates confounding effects due to differences in forcing data, isolating and clarifying the effects of land cover.

The diurnal cycle of Rn was captured well at all PFTs in both PTCLM4.5 and VR-CESM1.3; however, modeled albedo remained high during periods of snowmelt when tower albedo indicated snow-free conditions. We suspect this offset is related to melt patterns below the net radiometer footprint identified in March 2017 (Fig. 15). Snowmelt occurs earlier in the footprint of the net radiometer, which has a taller canopy with stiffer, untilled vegetation that is not as susceptible to compaction as the grasses that were tilled just beyond the footprint of the tower. Detailed snowpack conditions are not available for 2014–2016, so we cannot draw any conclusions on the fidelity of snowpack simulation in PTCLM at the open field sites at this time. Site visits in winter 2016/2017 confirmed that a large melt puddle forms below the net radiometer footprint well before the rest of the field begins to melt out (Fig. 15).

During the growing season, the diurnal cycle of net radiation is simulated well in PTCLM and VR-CESM; however, the partitioning of sensible and latent heat revealed strong biases in the forested sites. Based on flux tower observations, summertime λE tended to be higher over forested lands compared to deforested lands, but this pattern was not reflected in either PTCLM4.5 or VR-CESM1.3. Watershed scale studies (e.g., Ford et al. 2011) generally confirm that λE is greater in forested landscapes compared to deforested lands, so the discrepancy between the observations and the model is more likely due to model simulation of λE than due to observational biases. When we forced PTCLM4.5 with flux tower meteorology, modeled summertime H was overestimated and λE was underestimated relative to the flux tower estimates at the forested sites at UNH and Duke. Given the compensating biases in latent and sensible heat, it is not surprising that the modeled PTCLM4.5 summer β for forests was higher than the flux tower β (Table 3). Despite the biases in H and λE, the amplitude of the seasonal cycle in monthly β was generally well captured at the Duke sites (Fig. 11).

There are several possible reasons for the biases in latent and sensible heat for the forested PFTs simulated in this study. In CLM4.5, latent and sensible heat fluxes depend on PFT-specific aerodynamic parameters that determine resistance to heat, moisture, and momentum transfer and PFT-specific photosynthetic parameters that determine stomatal resistance, photosynthesis, and transpiration (Oleson et al. 2013). While these values may represent average values across PFTs on a global scale, the species at individual flux tower sites evaluated using PTCLM4.5 may differ from global PFT averages. Recent work with CLM5 has shown that the choice of empirical or optimized stomatal conductance models has little effect on evapotranspiration; however, species-specific parameters can result in high sensitivity and biases in evapotranspiration (Franks et al. 2018).

The addition of a multilayer canopy model in newer versions of CLM4.5 demonstrates reduced biases in latent and sensible heat (Bonan et al. 2018). Additionally, the influence of biogeochemical cycling on simulation of surface energy fluxes could be explored in more detail in future versions of CLM. The PTCLM4.5 and CESM1.3 simulations in this study were run in satellite phenology (CLM4.5-SP) mode; the biogeochemistry model (CLM4.5-BGC) was not active. For CESM1.3, this means that leaf area and stem area indices (LAI, SAI) and vegetation heights were prescribed in CLM4.5-SP from MODIS-based climatological estimates of LAI and SAI. For PTCLM4.5-SP, one can prescribe LAI, SAI, and canopy top and bottom heights to more closely match observations, though the values will not change dynamically with meteorological forcing and nutrient availability (e.g., nitrogen). Experiments running CLM4.5 in BGC mode were not conducted here but would be important to compare with SP mode in future versions of CLM to evaluate the impact on energy and water fluxes, as has been done in CLM4.0 (Lawrence et al. 2011).

Soil column sharing among PFTs within the vegetated land unit of a VR-CESM1.3 grid cell also affects partitioning of latent and sensible heat in CLM4.5 (Schultz et al. 2016). In a grid cell corresponding to the location of the Duke sites, the effect of soil column partitioning reduced (increased) H and λE by 10 W m−2 and increased (reduced) ground heat flux (G) by 20 W m−2 for forested (grass) PFTs. Soil column partitioning could therefore explain about 10% of the bias in latent heat and sensible heat at the Duke-hardwood and UNH-hardwood sites and the Duke-pine site.

While large biases in modeled growing season G were identified at the Duke-grass open field site and Duke-hardwood hardwood site, it should be noted that large uncertainties in the measurement of G at the Duke Ameriflux sites—resulting from a combination of soil heterogeneity that may not be representative of the eddy covariance footprint and a lack of energy balance closure, estimated at 20% imbalance (Wilson et al. 2002)—could account for much of the model bias.

We do not suspect that biases in H and λE would be alleviated by improvement in simulation of rah or ram because the largest differences in aerodynamic resistance parameters (raero, rah, and ram) occurred at night over forested canopies. We see little divergence in modeled rah and ram for any of the simulated land cover types; however rah and ram are generally much greater at night compared to raero. This could be due to u* filtering and exclusion of stable boundary layer conditions at night in the observations, biasing raero values low relative to rah and ram. Additionally, the PTCLM4.5 parameterization of vegetation properties such as canopy height is uniform in the model, but variable in the observations.

5 Conclusions

We tested the ability of the coupled VR-CESM1.3 and uncoupled PTCLM4.5 to simulate key surface properties and energy fluxes for common plant functional types in the Eastern USA. Results demonstrated model biases in turbulent fluxes for forested PFTs that in some cases were improved with coupling to the atmosphere and that the variable-resolution grids do not adversely impact simulation of surface energy fluxes compared to the uniform 1° CEMS grid.

Future experiments should include VR-CESM runs conducted with CLM-BGC, in which LAI, SAI, and other vegetation-related variables dynamically respond to surface climate forcing, and in-depth evaluation of carbon fluxes could be evaluated. Additionally, the VR-CESM simulations presented here were limited to the PFTs available in tower clusters in the Eastern USA. Additional simulations that evaluate tropical and high-latitude PFTs have not been evaluated here but would be important to consider for future simulations.

In contrast to uncoupled simulations forced by reanalysis data, VR-CESM1.3 has the advantage of a freely evolving coupled climate system that is necessary for investigating feedbacks between LULCC and other anthropogenic forcings (e.g., greenhouse gases). The model grid configuration of VR-CESM1.3 with PFT-level (subgrid) output shows potential as a research tool for understanding how land cover influences surface climate without the confounding effects of differences in forcing and changes in atmospheric circulation imposed through traditional deforestation experiments (Lawrence et al. 2016).

References

Adegoke JO, Pielke R, Carleton AM (2007) Observational and modeling studies of the impacts of agriculture-related land use change on planetary boundary layer processes in the central US. Agric For Meteorol 142(2–4):203–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2006.07.013

Baidya Roy S (2003) A preferred scale for landscape forced mesoscale circulations? J Geophys Res 108(D22). https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD003097

Best MJ, Abramowitz G, Johnson HR, Pitman AJ, Balsamo G, Boone A, Cuntz M, Decharme B, Dirmeyer PA, Dong J, Ek M, Guo Z, Haverd V, van den Hurk BJJ, Nearing GS, Pak B, Peters-Lidard C, Santanello JA Jr, Stevens L, Vuichard N (2015) The plumbing of land surface models: benchmarking model performance. J Hydrometeorol 16(3):1425–1442. https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-14-0158.1

Blyth EM, Dolman AJ, Noilhan J (1994) The effect of forest on mesoscale rainfall: an example from HAPEX-MOBILHY. J Appl Meteorol 33(4):445–454. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1994)033<0445:TEOFOM>2.0.CO;2

Boisier JP, de Noblet-Ducoudré N, Pitman AJ, Cruz FT, Delire C, van den Hurk BJJM, van der Molen MK, Müller C, Voldoire A (2012) Attributing the impacts of land-cover changes in temperate regions on surface temperature and heat fluxes to specific causes: results from the first LUCID set of simulations. J Geophys Res 117:D12116. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD017106

Bonan GB (2008) Forests and climate change: forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 320:1444–1449. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1155121

Bonan GB, Patton EG, Harmon IN, Oleson KW, Finnigan JJ, Lu Y, Burakowski EA (2018) Modeling canopy-induced turbulence in the Earth system: a unified parameterization of turbulent exchange within plant canopies and the roughness sublayer (CLM-ml v0). Geosci Model Dev 11:1467–1496. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-1467-2018

Bright RM, Davin E, O’Halloran T, Pongratz J, Zhao K, Cescatti A (2017) Local temperature response to land cover and management change driven by non-radiative processes. Nat Clim Chang 7:296–302. https://doi.org/10.1038/NCLIMATE3250

Cheruy F, Dufresne JL, Hourdin F, Ducharne A (2014) Role of clouds and land-atmosphere coupling in midlatitude continental summer warm biases and climate change amplification in CMIP5 simulations. Geophys Res Lett 41:6493–6500. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL061145

Collow TW, Robock A, Wu W (2014) Influences of soil moisture and vegetation on convective precipitation forecasts over the United States Great Plains. J Geophys Res Atm 119:9338–9358. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JD021454

Courault D, Drobinski P, Brunet Y, Lacarrere P, Talbot C (2007) Impact of surface heterogeneity on buoyancy-driven convective boundary layer in light winds. Bound-Layer Meteorol 124:383–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-007-9172-y

Davin EL, de Noblet-Ducoudré N (2010) Climate impact of global-scale deforestation: radiative versus nonradiative processes. J Clim 23:97–112. https://doi.org/10.1175/2009JCLI3102.1

Davin EL, de Noblet-Ducoudré N, Friedlingstein P (2007) Impact of land cover change on surface climate: relevance of the radiative forcing concept. Geophys Res Lett 34:L13702. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL02678

de Noblet-Ducoudré N et al (2012) Determining robust impacts of land-use-induced land cover changes on surface climate over North America and Eurasia: results from the first set of LUCID experiments. J Clim 25:3261–3281. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00338.1

Detto M, Montaldo N, Albertson JD, Mancini M, Katul G (2006) Soil moisture and vegetation controls on evapotranspiration in a heterogeneous Mediterranean ecosystem on Sardinia, Italy. Water Resour Res 42:W08419. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005WR004693

Dickinson RE, Kennedy P (1992) Impacts on regional climate of Amazon deforestation. Geophys Res Lett 19:1947–1950

Diffenbaugh NS (2009) Influence of modern land cover on the climate of the United States. Clim Dyn 33:945–958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-009-0566-z

Dirmeyer PA (1994) Vegetation stress as a feedback mechanism in midlatitude drought. J Clim 7:1463–1483

Dirmeyer PA, Koster RD, Guo Z (2006) Do global models properly represent the feedbacks between land and atmosphere? J Hydrometeorol 7:1177–1198. https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM532.1

Dirmeyer PA et al (2012) Evidence for enhanced land-atmosphere feedback in a warming climate. J Hydrometeorol 13:981–995. https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-11-0104.1

Dirmeyer PA, Wang Z, Mbuh MJ, Norton HE (2014) Intensified land surface control on boundary layer growth in a changing climate. Geophys Res Lett 41:1290–1294. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013GL058826

Feddema JJ, Oleson KW, Bonan GB, Mearns LO, Buja LE, Meehl GA, Washington WM (2005) The importance of land-cover change in simulating future climates. Science 310:1674–1678. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1118160

Findell KL, Eltahir EAB (2003) Atmospheric controls on soil moisture-boundary layer interactions. Part II: feedbacks within the continental United States. J Hydrometeor 4:570–583. https://doi.org/10.1175/1525-7541(2003)004<0570:ACOSML>2.0.CO;2

Findell KL, Gentine P, Lintner BR, Kerr C (2011) Probability of afternoon precipitation in eastern United States and Mexico enhanced by high evaporation. Nat Geosci 4:434–439. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1174

Fischer EM, Seneviratne SI, Lüthi D, Schär C (2007) Contribution of land-atmosphere coupling to recent European summer heat waves. Geophys Res Lett 34:L06707. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL029068

Ford CR, Laseter SH, Swank WT, Vose JM (2011) Can forest management be used to sustain water-based ecosystem services in the face of climate change? Ecol Appl 21:2049–2067. https://doi.org/10.1890/10-2246.1

Franks PJ, Bonan GB, Berry JA, Lombardozzi DL, Michele Holbrook N, Herold N, Oleson KW (2018) Comparing optimal and empirical stomatal conductance models for application in Earth system models. Glob Chang Biol, in press 24:5708–5723

Garcia-Carreras L, Parker DJ, Taylor CM, Reeves CE, Murphy JG (2010) Impact of mesoscale vegetation heterogeneities on the dynamical and thermodynamic properties of the planetary boundary layer. J Geophys Res 115:D03102. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JD012811

Gates WL (1992) An AMS continuing series: global change--AMIP: The Atmopsheric Model Intercomparison Project. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(1992)073<1962:ATAMIP>2.0.CO;2

Guo Z, Dirmeyer PA, DelSole T (2012) Rebound in atmospheric predictability and the role of the land surface. J Clim 25:4744–4749. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00651.1

Hirschi M, Seneviratne SI, Alexandrov V, Boberg F, Boroneant C, Christensen OB, Formayer H, Orlowsky B, Stepanek P (2011) Observational evidence for soil-moisture impact on hot extremes in southeastern Europe. Nat Geosci 4:17–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1032

Hsieh C-I, Katul G, Chi T-w (2000) An approximate analytical model for footprint estimation of scalar fluxes in thermally stratified atmospheric flows. Adv Water Resour 23:765–772

Huang X, Rhoades AM, Ullrich PA, Zarzycki CM (2016) An evaluation of the variable-resolution CESM for modeling California’s climate. J Adv Model Earth Syst 8:845–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015MS000559

Hurrell JW et al (2013) The community earth system model: a framework for collaborative research. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 93:1339–1360. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00121.1

Juang J-Y, Porporato A, Stoy PC, Siqueira MS, Oishi AC, Detto M, Kim H-S, Katul G (2007a) Hydrologic and atmospheric controls on initiation of convective precipitation events. Water Resour Res 43:W03421. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006WR004954

Juang J-Y, Katul GG, Siqueira MBS, Stoy PC, Novick K (2007b) Separating the effects of albedo from eco-physiological changes on surface temperature along a successional chronosequence in the southeastern United States. Geophys Res Lett 34:L21408. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL031296

Koster RD et al (2011) The second phase of the global land-atmosphere coupling experiment: soil moisture contributions to subseasonal forecast skill. J Hydrometeorol 12:805–822. https://doi.org/10.1175/2011JHM1365.1

Lawrence PJ, Chase TN (2010) Investigating the climate impacts of global land cover change in the community climate system model. Int J Climatol 30:2066–2087. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.2061

Lawrence DL et al (2011) Parameterization improvements and function and structural advances in version 4 of the community land model. J Adv Model Earth Syst 3:M03001, 27 pp. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011MS000045

Lawrence DL et al (2016) The Land Use Model Intercomparison Project (LUMIP) contribution to CMIP6: rationale and experimental design. Geosci Model Dev 9:2973–2998. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-2973-2016

Lee X et al (2011) Observed increase in local cooling effect of deforestation at higher latitudes. Nature 479:384–387. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10588

Lorenz R, Davin EL, Seneviratne SI (2012) Modeling land-climate coupling in Europe: impact of surface representation on climate variability and extremes. J Geophys Res Atmos 117:D20109. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JD017755

Luyssaert S et al (2014) Land management and land-cover change have impacts of similar magnitude on surface temperature. Nat Clim Chang 4:389–393. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2196

Miralles DG, Teuling AJ, van Heerwaarden CC, Vilá-Guerau de Arellano J (2014) Mega-heatwave temperatures due to combined soil desiccation and atmospheric heat accumulation. Nat Geosci 7:345–349. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2141

Myoung B, Nielsen-Gammon JW (2010) The convective instability pathway to warm season drought in Texas. Part II: free-tropospheric modulation of convective inhibition. J Clim 23:4474–4488. https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JCLI2947.1

Neal RB et al (2010) Description of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model (CAM5.0). NCAR Tech. Note NCAR/TN-4861STR. 268 pp. Available online at www.cesm.ucar.edu/models/cesm1.1/cam/docs/description/cam5_desc.pdf. Accessed 1 Sept 2017

Novick KA, Oren R, Stoy P, Siqueira MBS, Katul GG (2009) Nocturnal evapotranspiration in eddy covariance records from three co-located ecosystems in the southeastern US: the effect of gapfilling methods on estimates of annual fluxes. Agric For Meteorol 149:1491–1504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2009.04.005

Novick KA, Oishi AC, Ward EJ, Siqueira MBS, Juang J-Y, Stoy PC (2015) On the difference in the net ecosystem exchange of CO2 between deciduous and evergreen forests in the southeastern United States. Glob Chang Biol 21:827–842. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12723

Oleson KA et al (2013) Technical description of version 4.5 of the Community Land Model (CLM). NCAR/TN-503+STR. Available at: http://www.cesm.ucar.edu/models/cesm1.2/clm/CLM45_Tech_Note.pdf. Accessed 28 Dec 2015

Pitman AJ et al (2009) Uncertainties in climate responses to past land cover change: first results from the LUCID intercomparison study. Geophys Res Lett 36:L14814. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL039076

Reichstein M et al (2005) On the separation of net ecosystem exchange into assimilation and ecosystem respiration: review and improved algorithm. Glob Chang Biol 11:1424–1439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.001002.x

Rhoades AM, Huang X, Ullrich PA, Zarzycki CM (2016) Characterizing Sierra Nevada snowpack using variable-resolution CESM. J Appl Meteor Climatol 55:173–196. https://doi.org/10.1175/JAMC-D-15-0156.1

Santanello JA Jr, Peters-Lidard CD (2013) Diagnosing the nature of land-atmosphere coupling: a case study of dry/wet extremes in the U.S. Southern Great Plains. J Hydrometeorol 14:3–24. https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-12-023.1

Schultz NM, Lee X, Lawrence PJ, Lawrence DM, Zhao L (2016) Assessing the use of sub-grid land model output to study impacts of land cover change. J Geophys Res Atmos 121:6133–6147. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JD025094

Seneviratne SI, Lüthi D, Litschi M, Schär C (2006) Land-atmosphere coupling and climate change in Europe. Nature 443:205–209. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05095

Shukla J, Nobre C, Sellers P (1990) Amazon deforestation and climate change. Science 247:1322–1325

Stoy PC et al (2006) Separating the effects of climate and vegetation on evapotranspiration along a successional chronosequence in the southeastern US. Glob Chang Biol 12:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01244.x

Tawfik AB, Dirmeyer PA, Santanello JA (2015) The heated condensation framework. Part I: description and Southern Great Plains case study. J Hydrometeorol 16:1929–1945. https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-14-0117.1

Taylor KE (2001) Summarizing multiple aspects of model performance in a single diagram. J Geophys Res 106(D7):7183–7192. https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JD900719

Taylor CM, de Jeu RAM, Guichard F, Harris PP, Dorigo WA (2012) Afternoon rain more likely over drier soils. Nature 489:423–426. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11377

Teuling A et al (2010) Contrasting response of European forest and grassland energy exchange to heatwaves. Nat Geosci 3:722–727. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo950

Teuling AJ et al (2013) Evapotranspiration amplifies European summer drought. Geophys Res Lett 40:2071–2075. https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50495

Viterbo P, Beljaars ACM (1995) An improved land surface parameterization scheme in the ECMWF model and its validation. J Clim 8:2716–2748

Weaver CP, Baidya Roy S, Avissar R (2002) Sensitivity of simulated mesoscale atmospheric circulations resulting from landscape heterogeneity to aspects of model configuration. J Geophys Res 107:8041. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD000376

Webb EK, Pearman GI, Leuning R (1980) Correction of flux measurements for density effects due to heat and water vapour transfer. Q J R Meteorol Soc 106:85–100

Wickham JD, Wade TG, Riiters KH (2013) Empirical analysis of the influence of forest extent on annual and seasonal surface temperatures for the continental United States. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 22:620–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12013

Wilson K et al (2002) Energy balance closure at FLUXNET sites. Agric For Meteorol 113:223–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1923(02)00109-0

Zarzycki CM, Jablonowski C (2014) A multidecadal simulation of Atlantic tropical cyclones using a variable-resolution global atmospheric general circulation model. J Adv Model Earth Syst 6:805–828. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014MS000352

Zarzycki CM, Levy MN, Jablonowski C, Overfelt JR, Taylor MA, Ullrich PA (2014) Aquaplanet experiments using CAM’s variable-resolution dynamical core. J Clim 27:5481–5503. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00004.1

Zarzycki CM, Jablonowski C, Thatcher DR, Taylor MA (2015) Effects of localized grid refinement on the general circulation and climatology in the community atmosphere model. J Clim 28:2777–2803. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00599.1

Zhao K, Jackson RB (2014) Biophysical forcings of land-use changes from potential forestry activities in North America. Ecol Monogr 84:329–353

Acknowledgments

We would like to recognize the computational support provided by the NCAR Computational and Information Systems Laboratory for computing, processing, and data storage. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments to improve the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the support of the National Science Foundation Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) through the New Hampshire EPSCoR Ecosystems and Society Program (EPS-1101245) and the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (AES/Hatch Accession #1006997). The National Center for Atmospheric Research is sponsored by the National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 393 kb)

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Burakowski, E.A., Tawfik, A., Ouimette, A. et al. Simulating surface energy fluxes using the variable-resolution Community Earth System Model (VR-CESM). Theor Appl Climatol 138, 115–133 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-019-02785-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-019-02785-0