Abstract

In the year 2005, we obtained first evidence for the existence of weakly bound quantum states of three resonantly interacting particles, as predicted 35 years earlier by Vitaly Efimov. In our laboratory, the striking signature of an Efimov state was a giant three-body loss resonance observed in a gas of cesium atoms that was evaporatively cooled to temperatures of about 10 nanokelvin. Here, I will give a short personal account on what prepared the ground for this observation, on how things finally happened in our laboratory, and on how our experiments then developed further.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It has been a great honor for me to receive the inaugural Faddeev medal together with Vitaly Efimov at the International Conference on Few-Body Problems in Caen in July 2018, and I am very grateful to the few-body community for this tremendous recognition. Faddeev was a truly outstanding mathematical physicist. My scientific profile is a completely different one. As an experimental physicist, my world is the laboratory, which is full of lasers, optics, electronics, vacuum equipment, and other things. So, I would have never expected to receive an award named after an eminent mathematical physicist, but it happened thanks to Efimov’s paradigmatic theoretical work [1, 2] in the field of few-body physics.

In this short article, I will give a personal account on how it finally happened in the laboratory that first traces of Efimov’s mysterious states were found. I will focus on our early work on ultracold cesium atoms and a few more recent developments. For comprehensive overviews of the whole field, including references to experimental investigations on many other systems, the reader is referred to excellent review articles [3,4,5,6,7].

2 How the Ground was Prepared

It was in the 1990’s when I first heard about Efimov states. In a colloquium talk at Heidelberg university, J. P. Toennies reported on He molecular beam diffraction experiments [8] and pointed out prospects for observing an Efimov state in the He\(_3\) trimer. I did not understand what kind of states he was talking about, but it sounded bizarre, mysterious, and very interesting. In 1999, I heard again about Efimov states. This was in a talk presented by V. Vuletić at the International Conference on Laser Spectroscopy in Innsbruck [9]. He reported on the observation of narrow magnetic-field dependent resonances in an ultracold cesium gas at a few \(\mu \)K, and discussed Efimov quantum states as a possible explanation.Footnote 1

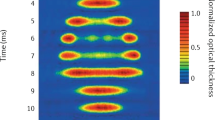

Then, stimulated by theoretical and experimental advances in ultracold quantum gases and a portion of good luck, it finally happened in our cesium laboratory (see Fig. 1) in September 2005. Here I will summarize the main ingredients of this story.

2.1 Three-Body Recombination in Ultracold Gases

The detailed understanding of loss processes plays a very important role for experiments on ultracold quantum gases. For example, efficent evaporative cooling into the quantum-degenerate regime, where Bose–Einstein condensates or degenerate Fermi gases are formed, is only possible if loss processes are sufficiently weak. In the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, this motivated theoretical studies on the role of three-body recombination in Bose gases. In a three-body recombination process, two of the three colliding atoms form a dimer, the binding energy of which is released into the kinetic motion of the recombination products. For ultracold gases, the energy release in such a process is usually large compared to the depth of the atom trap that contains the gas. Therefore, three-body recombination usually leads to trap losses. This is an unwanted effect, if one wants to achieve efficient evaporative cooling, but trap loss can also serve as a probe for resonant few-body phenomena.

In ultracold gases, the interaction strength is (in most cases) characterized by a single parameter, the s-wave scattering length a. In 1996, Fedichev et al. [11] pointed out that three-body loss in Bose gases is subject to a general scaling proportional to \(a^4\). For experiments on Bose gases at large scattering length this implies fast losses. In the years 1999–2001, the work of Esry et al. [12] and Bedaque et al. [13], and Braaten and Hammer [14], revealed additional structure on top of this general \(a^4\)-scaling behavior. For \(a>0\), additional recombination minima were identified and, for \(a<0\), pronounced loss resonances were predicted. In both cases, the additional structure shows a logarithmically periodic dependence on the scattering length a with the Efimov period of 22.7. The loss resonances for \(a<0\) were identified as Efimov resonances. Here an Efimov three-body state crosses the threshold of three free atoms, which opens up a very fast recombination path. In such a process, three colliding atoms couple to an Efimov state, which then rapidly decays into a dimer and a free atom.

2.2 Towards BEC of Cesium and a Strange Observation

After the demonstration of Bose–Einstein condensation (BEC) in ultracold gases of Rb and Na atoms in 1995 [15, 16], other groups tried to achieve BEC of Cs by using basically the same magnetic trapping and evaporative cooling techniques. However, Cs turned out to be special and the experiments suffered from fast, depolarizing two-body collisional losses [17, 18]. The reason for this unusual behavior was then understood as a result of resonant quantum-mechanical scattering in combination with strong higher-order coupling effects for heavy atoms [19, 20].

In an optical dipole trap [21], the atoms can be prepared in the lowest internal Zeeman sub-level where they are immune against two-body losses, and full advantage can be taken from the tunability of the scattering length provided by Feshbach resonances [10]. Back in the 1990’s we started our Cs experiments with the goal to achieve BEC in an optical dipole trap [22]. In such traps, three-body collisions remain as the dominant source of losses and thus we had to understand the role of three-body decay. Our main findings from these experiments are published in Ref. [23]. After identifying the optimum conditions for evaporative cooling we finally achieved BEC of Cs in October 2002 [24].

Early, unpublished observation of the low-field Cs Efimov resonance. The data were taken in August 2002 and show the fraction of Cs atoms remaining after a 10-s hold time in a CO\(_2\) laser trap as a function of the applied magnetic bias field. The sample was prepared with initially \(1.3 \times 10^6\) atoms at a temperature of 450 nK. The solid red line is smoothed curve through the whole set of points. In Ref. [23] we showed the points above 10 G, but rejected the data at lower field because of a distortion of the trapping potential caused by the magnetic levitation field [24] applied in these experiments. It later turned out that the loss feature near 7.5 G was not an effect of trap distortion, but marked an Efimov resonance

In experiments carried out in summer 2002, we scanned a range of magnetic fields up to 100 G and measured three-body losses. In Ref. [23] we published our observations made between 10 and 100 G. In this early work, we rejected the data taken below 10 G, because we considered them as not reliable. At low magnetic bias field, the trapping potential of our magnetic ‘levitation’ trap gets distorted by the curvature of the magnetic field, which made the interpretation of the observations unclear. In Fig. 2, we now show the original data from these experiments in a range between 3 and 50 G, including the region of unpublished data below 10 G. A broad loss feature shows up around 7.5 G, which looks different from the narrow Feshbach resonances observed at higher fields. We of course noticed this peculiar feature, but suspected it to be an artefact caused by the distorted trapping potential. We then focused our attention on attaining Cs BEC and almost forgot about the strange 7.5 G loss feature.

2.3 Workshop in Seattle as Key Event

Three years later, in August 2005, I attended the workshop on New Developments in Quantum Gases at the Institute for Nuclear Theory at the University of Washington in Seattle. My main interest was in strongly interacting Fermi gases as one of the main workshop topics. Very interesting talks were presented also on advances in three-body theory, including the role of Efimov states. Some presentations and discussions reminded me on the strange feature we had observed 3 years before, and this made me think about it again.

On the last day of the workshop, Vitaly Efimov presented a talk with the title “How to find a new effect?” He packaged his messages in a collection of personal anecdotes, and one of them was about the Young Pioneers’ motto “Always be ready!”. My interpretation of this message was that one should be always open to unexpected things and one should be always ready to take the opportunity. This was a clear signal for me to revisit the strange loss feature in Cs, and I immediately called my team to conduct a new series of experiments. This turned out to be the starting point of many years of research on Efimov states in ultracold gases.

3 Experiments on Ultracold Cesium Gases

3.1 First Evidence for an Efimov State

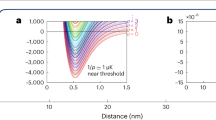

Our first experiments dedicated to Efimov states were carried out in Sept. 2005 [25]. We optimized our optical trapping schemes, eliminated the problems with the magnetic field curvature, and cooled our Cs samples much further down (to about 10 nK). With an optimized system, we then observed the three-body recombination resonance at 7.5 G again, and the signal was much more clear than in our previous experiments. The results are shown in Fig. 3 on a scattering length scale; here a magnetic field of 7.5 G corresponds to \(a = -850\,a_0\), where \(a_0\) is Bohr’s radius. In the low magnetic field region of Cs, the scattering length is large and negative, which is right in the regime where three-body Efimov resonances were to be expected. Our observation closely resembled the prediction from Ref. [12] and, moreover, it could be fitted very well with an analytic expression provided by Refs. [3, 14].

Efimov resonances observed in ultracold cesium. The left-hand panel shows the original observation from our first article [25], published in 2006. The solid lines are fits by effective field theory for zero temperature [3]. The Efimov resonance was found at a scattering length of about \(-850\,a_0\) (corresponding to a magnetic field of 7.5 G). The right-hand panel shows the observation of a higher resonance (near \(-20{,}000\,a_0\)) from Ref. [26], which was published in 2014. The solid line shows a fit by a finite-temperature theory. Three-body losses are quantified in terms of a recombination length \(\rho _3\) [12] or the three-body loss coefficient \(L_3 \propto \rho _3^4\). For details refer to the original publications [25, 26]

We also investigated a region of higher magnetic fields (above 17 G), where the s-wave scattering length becomes positive. Here we found a recombination minimum as another feature related to Efimov physics (see inset in the left-hand panel of Fig. 3), which turned out to be very useful for efficient evaporative cooling [24, 27]. All these observations corresponded very well to the key theoretical predictions on manifestations of Efimov states in ultracold gases [3, 12,13,14]. In particular, the observed recombination resonance was found in striking agreement with the prediction for an Efimov state coupling to three colliding atoms. This made us very confident in our interpretation!

3.2 Exploring the Efimov Scenario

A central feature of Efimov’s scenario is the discrete scale invariance of the infinite series of quantum states, for which the famous factor of 22.7 was predicted. Experimentally, however, it is very difficult to take even one step on the ladder. This is because extremely large values of the scattering length are required, and the reduction of the energy scale by a factor of \(1/22.7^2 \approx 1/500\) makes the situation extremely sensitive to finite-temperature effects. Using the particularly favorable scattering properties of cesium atoms in a region of high magnetic fields (around 800 G) [28] and employing a finite-temperature analysis [29], we could finally identify a higher Efimov three-body resonance [26] (see right-hand panel in Fig. 3) and extract an experimental value for the scaling factor. Our corresponding result was a factor of 21.0 (1.3), consistent with the theoretical prediction.

We have also investigated the case of positive scattering length (\(a>0\)), where a weakly bound dimer state is present. We prepared samples of weakly bound Cs\(_2\) dimers together with free atoms and studied the inelastic collisional properties. Here, an atom colliding with a dimer can couple to an Efimov trimer, which causes rapid losses. In Refs. [30, 31], we clearly identified such atom-dimer scattering resonances and investigated their connections to Efimov’s scenario.

An important question for any real three-body system is where the series of Efimov states starts. In theory, this is described by a free three-body parameter, which cannot be derived from universal theories at large scattering lengths. In our experimental work [32], we compared four different Efimov resonances in cesium and showed that the resonances appeared essentially at the same values of the scattering length. This ruled out a random three-body parameter and suggested (together with observations in other systems) that the appearance of Efimov states in real atomic systems is governed by the van-der-Waals potential, which describes the interaction at long range. These observations triggered theoretical investigations, which then confirmed and explained a novel kind of universality in real atomic systems [33,34,35].

3.3 Beyond Three-Body Physics

Guided by theoretical work that suggested the existence of universal four-body states tied to Efimov trimers [36, 37], we conducted experiments on four-body recombination in cesium and observed signatures of the two predicted universal four-body states [38]. We later extended this work to five-body recombination and universal five-body states [39]. Our work provided strong evidence for the existence of a whole scenario of universal N-body states as predicted in theoretical work [40]. This shows that the relevance of Efimov’s scenario goes far beyond three-body physics and underlines it paradigmatic role for the whole field of few-body physics.

4 Conclusion

Our work on Cs has been complemented by many observations on Efimov states in other ultracold atomic systems [5,6,7], and also the elusive Efimov trimer of He has been observed in a molecular beam experiment [41]. Thanks to parallel advances in theory and experiment we have gained remarkable understanding of three-body phenomena in ultracold gases [5,6,7], and we have understood their great relevance in the general context of many-body quantum systems. Few-body physics has opened up a new branch in cold-atom physics, which in turn has provided new momentum for advancing our general knowledge on few-body quantum systems.

Notes

It soon turned out that the observed resonances were something else (narrow Feshbach resonances caused by higher partial waves [10]), but ironically their experiments were indeed very close to conditions under which an Efimov state occurs, only their samples were somewhat too hot to observe it.

References

V. Efimov, Phys. Lett. B 33, 563 (1970)

V. Efimov, Sov. J. Nucl. Phys. 12, 589 (1971)

E. Braaten, H.W. Hammer, Phys. Rep. 428, 259 (2006)

A.S. Jensen, Few-Body Syst. 51, 77 (2011)

C.H. Greene, P. Giannakeas, J. Pérez-Ríos, Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035006 (2017)

P. Naidon, S. Endo, Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 056001 (2017)

J.P. D’Incao, J. Phys, J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 51, 043001 (2018)

W. Schöllkopf, J.P. Toennies, Science 266, 1345 (1994)

V. Vuletić, A.J. Kerman, C. Chin, S. Chu, in Laser Spectroscopy, XIV International Conference, Innsbruck, Austria, June 7-11, 1999, ed. by R. Blatt, J. Eschner, D. Leibfried, F. Schmidt-Kaler (World Scientific, Singapore, 1999)

C. Chin, R. Grimm, P.S. Julienne, E. Tiesinga, Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1225 (2010)

P.O. Fedichev, M.W. Reynolds, G.V. Shlyapnikov, Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 2921 (1996)

B.D. Esry, C.H. Greene, J.P. Burke, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1751 (1999)

P.F. Bedaque, E. Braaten, H.W. Hammer, Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 908 (2000)

E. Braaten, H.W. Hammer, Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 160407 (2001)

M.H. Anderson, J.R. Ensher, M.R. Matthews, C.E. Wieman, E.A. Cornell, Science 269, 198 (1995)

K.B. Davis, M.O. Mewes, M.R. Andrews, N.J. van Druten, D.S. Durfee, D.M. Kurn, W. Ketterle, Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 3969 (1995)

J. Söding, D. Guéry-Odelin, P. Desbiolles, G. Ferrari, J. Dalibard, Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1869 (1998)

J. Arlt, P. Bance, S. Hopkins, J. Martin, S. Webster, A. Wilson, K. Zetie, C.J. Foot, J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 31(7), L321 (1998)

C. Chin, V. Vuletić, A.J. Kerman, S. Chu, Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2717 (2000)

P.J. Leo, C.J. Williams, P.S. Julienne, Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2721 (2000)

R. Grimm, M. Weidemüller, Yu.B. Ovchinnikov, Adv. At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 42, 95 (2000)

H. Engler, I. Manek, U. Moslener, M. Nill, Yu.B. Ovchinnikov, U. Schlöder, U. Schünemann, M. Zielonkowski, M. Weidemüller, R. Grimm, Appl. Phys. B 67, 709 (1998)

T. Weber, J. Herbig, M. Mark, H.-C. Nägerl, R. Grimm, Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 123201 (2003)

T. Weber, J. Herbig, M. Mark, H.-C. Nägerl, R. Grimm, Science 299, 232 (2003)

T. Kraemer, M. Mark, P. Waldburger, J.G. Danzl, C. Chin, B. Engeser, A.D. Lange, K. Pilch, A. Jaakkola, H.-C. Nägerl, R. Grimm, Nature (London) 440, 315 (2006)

B. Huang, L. Sidorenkov, R. Grimm, J.M. Hutson, Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 190401 (2014)

T. Kraemer, J. Herbig, M. Mark, T. Weber, C. Chin, H.-C. Nägerl, R. Grimm, Appl. Phys. B 79, 1013 (2004)

M. Berninger, A. Zenesini, B. Huang, W. Harm, H.-C. Nägerl, F. Ferlaino, R. Grimm, P.S. Julienne, J.M. Hutson, Phys. Rev. A 87, 032517 (2013)

B. Huang, L.A. Sidorenkov, R. Grimm, Phys. Rev. A 91, 063622 (2015)

S. Knoop, F. Ferlaino, M. Mark, M. Berninger, H. Schöbel, H.-C. Nägerl, R. Grimm, Nat. Phys. 5, 227 (2009)

A. Zenesini, B. Huang, M. Berninger, H.-C. Nägerl, F. Ferlaino, R. Grimm, Phys. Rev. A 90, 022704 (2014)

M. Berninger, A. Zenesini, B. Huang, W. Harm, H.-C. Nägerl, F. Ferlaino, R. Grimm, P.S. Julienne, J.M. Hutson, Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 120401 (2011)

J. Wang, J.P. D’Incao, B.D. Esry, C.H. Greene, Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 263001 (2012)

R. Schmidt, S. Rath, W. Zwerger, Eur. Phys. J. B 85, 1 (2012)

P. Naidon, S. Endo, M. Ueda, Phys. Rev. A 90, 022106 (2014)

H.W. Hammer, L. Platter, Eur. Phys. J. A 32, 113 (2007)

J. von Stecher, J.P. D’Incao, C.H. Greene, Nat. Phys. 5, 417 (2009)

F. Ferlaino, S. Knoop, M. Berninger, W. Harm, J.P. D’Incao, H.-C. Nägerl, R. Grimm, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 140401 (2009)

A. Zenesini, B. Huang, M. Berninger, S. Besler, H.-C. Nägerl, F. Ferlaino, R. Grimm, C.H. Greene, J. von Stecher, New J. Phys. 15(4), 043040 (2013)

J. von Stecher, J. Phys. B 43, 101002 (2010)

M. Kunitski, S. Zeller, J. Voigtsberger, A. Kalinin, L.P.H. Schmidt, M. Schöffler, A. Czasch, W. Schöllkopf, R.E. Grisenti, T. Jahnke, D. Blume, R. Dörner, Science 348, 551 (2015)

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck. Over the almost 10 years of our experimental research on Efimov states in cesium, many members of our group have given essential contributions. I would like to highlight the particularly important roles of H. -C. Nägerl and F. Ferlaino, who guided our projects as co-investigators at different stages. I would like to thank C. Chin for many insights on the mysteries of cesium and for his participation in our first experiments. Moreover, I would like to thank a great team of postdocs (S. Knoop, A. Zenesini, L. Sidorenkov), Ph.D. students (T. Kraemer, M. Mark, J. G. Danzl, B. Engeser, A. D. Lange, K. Pilch, M. Berninger, B. Huang), diploma/master students (P. Waldburger, H. Schöbel, W. Harm, S. Besler) and guests (A. Jaakkola, K. M. O’Hara), who all have contributed to our research program at various stages. Finally, I would like to acknowledge invaluable support by our theory collaborators (J. D’Incao, P. S. Julienne, J. M. Hutson, J. von Stecher, C. Greene, D. S. Petrov), who guided us on uncharted scientific terrain and showed us new directions. I am greatly indebted to the Austrian Science Fund FWF for supporting our work on cesium quantum gases and Efimov states in various funding programs (Project Numbers P15114, P23106, F1516, Z106).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article belongs to the Topical Collection “Ludwig Faddeev Memorial Issue”.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Grimm, R. Efimov States in an Ultracold Gas: How it Happened in the Laboratory. Few-Body Syst 60, 23 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00601-019-1495-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00601-019-1495-y