Abstract

Purpose

This study investigated the impact of sidedness of colorectal cancer (CRC) in elderly patients on the prognosis.

Methods

In a sub-analysis of a multicenter case–control study of CRC patients who underwent surgery at ≥ 80 years old conducted in Japan between 2003 and 2007, both short- and long-term outcomes were compared between right-sided colon cancers (RCCs) and left-sided colorectal cancers (LCCs). RCCs were defined as those located from the cecum to the transverse colon.

Results

Among the 1680 patients who underwent curative surgery, 812 and 868 had RCCs and LCCs, respectively. RCCs were more frequent than LCCs in those who were female, had renal comorbidities, and had a history of abdominal surgery. Regarding tumor characteristics, RCCs were larger, invaded more deeply, and were diagnosed as either mucinous or signet ring-cell carcinoma more frequently than LCCs. Regarding the prognosis, patients with RCCs had a significantly longer cancer-specific survival (CS-S) and cancer-specific relapse-free survival (CS-RFS) than those with LCCs. Furthermore, sidedness was determined to be an independent prognostic factor for CS-S and CS-RFS.

Conclusion

RCCs, which accounted for half of the cases in patients ≥ 80 years old, showed better long-term outcomes than LCCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

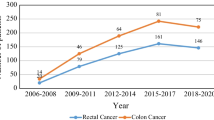

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1, 2], and its incidence is expected to increase with the rapid aging of society. In general, the risk of postoperative complications is higher among elderly patients who undergo surgery than among younger patients because elderly patients tend to have more preoperative comorbidities and are frailer than younger patients. Therefore, safe and effective treatment of elderly patients with CRC is a challenge that must be met [3]. However, whether or not laparoscopic surgery is beneficial and safe in such patients remains unclear.

Although laparoscopic surgery has the advantage of facilitating early recovery after surgery in the general population, its long operation time, use of pneumoperitoneum, and extreme head-down position during laparoscopic surgery remain concerns, as these affect circulatory dynamics and perioperative morbidity rates among the elderly. To address this issue, we conducted a multicenter observational study of 2065 elderly patients ≥ 80 years old who had undergone CRC surgery and demonstrated the safety of laparoscopic surgery with comparable long-term outcomes to open surgery, with the identification of some risk factors affecting short- and long-term outcomes [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

It was recently revealed that metastatic CRCs originating from the right-sided colon have a lower survival rate than those originating from the left-sided colon [11]. Similarly, other studies have shown that right-sided colon cancers (RCCs) have different prognoses from left-sided colorectal cancers (LCCs) [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Therefore, the location of the primary tumor is now recognized as a prognostic factor.

Most recently, many translational studies have elucidated that the different prognoses of RCCs and LCCs partially depend on the biological characteristics of the tumor, defined by molecular aberrations, including microsatellite instability (MSI) [12, 14, 15, 23, 26,27,28,29,30,31]. MSI-high CRCs are associated with a lower rate of distant or lymph node metastases [17, 26, 32] and lower recurrence rates after curative surgery, resulting in a longer survival after curative surgery than microsatellite stable CRCs [12, 26,27,28, 33]. However, once distant metastases develop, they are refractory due to resistance to 5-FU-based chemotherapy [28, 34,35,36,37].

MSI-high CRCs are also more frequently observed in cases of RCC [19, 26, 27] and in the elderly than in other patients [27]. From this standpoint, RCCs are expected to have a better prognosis after curative surgery than LCCs in the elderly population. Currently, evidence regarding whether RCCs or LCCs exhibit a better prognosis after surgery in elderly patients is lacking. A surveillance program and treatment strategy among elderly patients after surgery for CRC that considers surgical complications and prognoses based on differences in tumor location should be established. However, little is known regarding the impact of tumor location on short- and long-term outcomes after curative surgery for CRCs among the elderly.

In the present study, we analyzed a database from a large multicenter study focused on individuals ≥ 80 years old to elucidate the impact of CRC tumor location on survival outcomes among an elderly population.

Methods

Study design and participants

As described above, we previously reported a multicenter observational study of 2065 elderly patients ≥ 80 years old with a history of CRC surgery to assess the safety and efficacy of laparoscopic surgery [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Data were retrospectively collected between 2003 and 2007 from 41 institutes in the Japan Society of Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery. In the present study, using this dataset in accordance with the approval of the Ethics Review Board of the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum, we examined how the sidedness of CRCs influences the short-term surgical outcomes and survival among elderly patients ≥ 80 years old.

From the original cohort, we included all patients who were histologically diagnosed with colorectal adenocarcinoma and treated with either open or laparoscopic surgery. Patients with metastatic CRC at the time of the diagnosis and those who underwent non-curative surgery were excluded. As surveillance after surgery was performed in accordance with the standard protocols of individual institutions owing to the retrospective nature of this observational study, cases with missing data on relapse were excluded. A total of 1,680 patients who underwent curative surgery for pathological TNM stage 0 to III CRC were included and divided into RCC and LCC groups based on their embryologic origin. Specifically, RCCs were defined by a location from the cecum to the splenic flexure (midgut), whereas LCCs were defined by a location from the descending colon to the rectum (hindgut). Patient characteristics and short-term operative outcomes were studied in patients with stage 0–III CRC, and a survival analysis was performed in patients with stage II and III CRC (Fig. 1).

Statistical analyses

The following parameters were compared between the RCC and LCC groups: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance States Scale (ECOG-PS), American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) class, preoperative comorbidity, history of abdominal surgery, Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) TNM staging system (UICC TNM 7th edition), tumor diameter, and histological type of the tumor. The following short-term outcomes were also compared: approach (open versus laparoscopic), surgical duration, blood loss, blood transfusion, postoperative complications, and length of hospital stay.

Regarding long-term outcomes, the overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) were compared between the RCC and LCC groups. In addition to the OS and RFS, we analyzed the cancer-specific survival (CS-S) and cancer-specific RFS (CS-RFS), as older CRC patients may die of old age or other severe comorbidities independently of post-operative complications or CRC. In the CS-S and CS-RFS analyses, patients with a cause of death other than CRC were right-censored. Subsequently, multivariate analyses for the OS, RFS, CS-S, and CS-RFS were conducted using a Cox proportional hazards model balanced with the following variables: tumor location, age, sex, BMI, ASA class, comorbidity, previous abdominal surgery, TNM stage, histological findings, and surgical approach. The results are reported as the median and interquartile range for quantitative variables and as frequencies for categorical variables.

Comparisons were conducted using Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test for quantitative variables and Fisher’s exact test (binary) or Pearson’s Chi-squared test (more than three variables) for categorical variables. Survival time analyses were summarized using Kaplan–Meier curves and corresponding hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The results of the multivariate analysis for the OS, RFS, CS-S, and CS-RFS are presented as odds ratios (ORs) or HRs and 95% CIs, with corresponding p-values.

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package Social Statistics software program for Windows (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Analyzing The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Pancancer atlas, colorectal adenocarcinoma (COADREAD) dataset

The following parameters were extracted from the TCGA-Pancancer Atlas COADREAD dataset: age, sex, International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition (ICD-O-3) site code, MSIsensor score, and MSI MANTIS score. The tumor location was identified by the ICD-O-3 site code, and for cases unidentifiable by ICD-O-3, manual curation was performed by referring to the anatomical neoplasm subdivision in the dataset. MSI-high was defined as an MSIsensor score ≥ 3.5 or MSI MANTIS score ≥ 0.4 [38].

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients and tumors

Among the 1680 patients included in this study, 812 (48.3%) and 868 (51.7%) had RCCs and LCCs, respectively. The tumor locations are described in detail in Supplementary Table 1. There were significantly more females in the RCC group than in the LCC group. In this cohort, the rates of renal comorbidity and a history of abdominal surgery were also higher in the RCC group than in the LCC group. In contrast, there were no significant differences in the age, BMI, PS, ASA class, or comorbidities between the RCC and LCC groups.

Regarding the TNM staging system, tumors were larger and more invasive (higher T stage) in the RCC group than in the LCC group, although there were no significant differences in TNM stage or lymph node metastasis. Of note, the ratios of mucinous adenocarcinoma and signet ring cell carcinoma in the historical findings were greater among RCCs than among LCCs (Table 1).

The comparison of short-term outcomes between RCCs and LCCs

The surgical approach (open versus laparoscopic) and blood transfusion performance were not significantly different between the RCCs and LCCs. Surgeries for LCCs took longer to perform, had more blood loss, and required longer hospital stays than surgeries for RCCs. There was a trend toward fewer postoperative complications in LCCs than in RCCs, although the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2). According to the multivariate analyses, female sex, early tumor stage, and laparoscopic approach were independently associated with a lower morbidity rate (Table 3).

The comparison of long-term outcomes between RCCs and LCCs after curative surgery

In survival analyses, there were no marked differences in the OS or RFS between the RCC and LCC groups (Fig. 2A and B). However, the RCC group showed a better CS-S and CS-RFS rates than the LCC group (Fig. 2C and D). Next, we investigated the effect of sidedness on the pathological stages II and III. Although there was a consistent tendency toward a better prognosis in RCCs than in LCCs, these differences were not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, in the multivariate analysis using a Cox proportional hazard model, tumor sidedness was determined to be an independent prognostic factor associated with the CS-S and CS-RFS, with both being more favorable in the RCC group than in the LCC group. In addition to tumor sidedness, a lower BMI and higher TNM stage (for the CS-S) and renal comorbidity and a higher TNM stage (for the CS-RFS) were determined to be independent prognostic factors in this cohort (Table 4).

The comparison of survival outcomes between right- and left-sided colorectal cancers (pathological stage II–III). The overall survival (A), relapse-free survival (B), cancer-specific survival (C), and cancer-specific relapse-free survival (D). The data were summarized as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values based on a log-rank test

Frequency of MSI-high cases among the elderly by sidedness of CRC in the TCGA-COADREAD dataset

We next examined the impact of the MSI status on differences in the CS-S and CS-RFS in the elderly population. However, due to the study design and ethical review board, MSI status data and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks were unavailable. Therefore, instead of analyzing the MSI status in our cohort, we performed a public dataset analysis of the TCGA Cancer Atlas COADREAD dataset. Using this dataset, we analyzed the association between age, sex, and MSI status estimated using the MSIsensor and MSI MANTIS scores. MSI-high cases were more frequently observed among patients ≥ 80 years old with RCC than in those < 80 years old (Table 5).

Discussion

Sidedness of CRC is reportedly associated with genomic instability [12, 14, 15, 23, 26,27,28,29]. MSI-high CRCs is predominantly observed in the right-sided colon and more frequently in elderly females than in males [14, 15, 31, 32]. Consistent with these reported features of MSI-high CRCs, there were more females in the RCC group than in the LCC group in the present study (Table 1). Furthermore, the ratio of RCCs to LCCs was 1:1 in our cohort, although it was reported to be 3:7 in the general population. This is also consistent with previous studies reporting that RCCs were more frequent among the elderly than among younger patients [39]. In addition, mucinous adenocarcinomas and signet-ring cell carcinomas, both of which are characteristic histological features of MSI-high CRCs [31, 32], were found more frequently in the RCC group than in the LCC group. Taken together, these findings suggest that the elderly population has more MSI-high CRCs in the right-sided colon than the general population. In addition, our TCGA dataset analysis showed that MSI-high cases were remarkably frequent in RCC cases among elderly patients ≥ 80 years old (Table 5), although we did not examine MSI in our cohort.

This high frequency of MSI-high CRC in the elderly may have affected the survival outcomes after curative surgery in our cohort because of the low potential for distant metastasis and recurrence. Although there were no significant differences in the OS or RFS between the RCC and LCC groups, the RCC group tended to have better survival than the LCC group according to the CS-S and CS-RFS (Fig. 2). In subsequent multivariate analyses, tumor sidedness and TNM stage were common independent risk factors for the CS-S and CS-RFS (Table 4). However, despite the better prognosis in the RCC group than in the LCC group in our cohort, others have reported that RCCs have a worse prognosis than LCCs after surgery [17, 23]. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis including 15 independent studies concluded that RCCs had a worse OS than LCCs [24]. This discrepancy may be explained by the extremely high frequency of MSI-high CRC in patients who were ≥ 80 years old and had RCC. In our TCGA dataset analysis (Table 5), MSI-high CRC was more frequent in RCCs than in LCCs in all studied populations. Furthermore, MSI-high cases were much more frequent in patients ≥ 80 years old than in those < 80 years old. Although there are some issues regarding race and geographical differences in the TCGA dataset because of the worldwide nature of the TCGA Cancer Atlas project, the results from the TCGA dataset potentially support our conclusion that RCCs have a better prognosis than LCCs among elderly patients in Japan.

The definition of LCC remains controversial, although the present study also included the rectum. We included rectal cancers in the left-sided group based on a previous report that tumor sidedness simplifies the continuum in the mutational profile and consensus molecular subtype (CMS), which influences the OS. The relative prevalence of the CMS and MSI-high status is reportedly comparable among sigmoid, rectosigmoid, and rectal cancers [40]. Our results also indicated that the CS-S in rectal cancers from rectum/above and rectum/below the peritoneal reflection cancers, despite the fact that there were no cases of preoperative radiotherapy for middle and lower rectal cancers, were not inferior to those of cancers from other anatomic sites, as shown in Supplementary Table 2, indicating that the prognosis of LCC is not worse than that of RCC due to the inclusion of the rectum.

As the present study targeted an elderly population, we focused on the association between the pre-operative conditions and short-term outcomes. Regarding differences in tumor sidedness, surgeries for LCCs appeared to be more invasive than those for RCCs based on surgical duration, blood loss, incidence of complications, and length of hospital stay (Table 2). However, tumor location had no notable impact on the morbidity rate in the multivariate analysis. Furthermore, laparoscopic surgery reduced the risk of post-operative complications in both the RCC and LCC groups (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Although care should be taken when dealing with male patients and those with a high TNM stage, a laparoscopic procedure can be safely chosen regardless of the tumor location (Table 3).

Several limitations associated with the present study warrant mention. First, because of the retrospective nature of the study, some biases could not be avoided, despite our efforts to reduce the impact of such biases using multivariate analyses. However, because all elderly patients who underwent surgery were enrolled during the investigation period (for five years, 2003–2007), and because there did not seem to be any extreme trends in the proportion of RCCs and LCCs among institutions (Supplementary Fig. 3), the results are thought to represent the current situation in Japan to some degree. Second, almost no patients received adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III disease after curative surgery. MSI-high CRCs have been reported to be resistant to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), which may affect survival outcomes [35]. The combination of oxaliplatin and 5-FU was reported to improve the RFS in MSI-high CRCs among the general population [35], although no survival benefits were achieved by adding oxaliplatin to 5-FU-based adjuvant chemotherapy in the elderly population [41,42,43]. In addition, the latest clinical trial revealed a notable effect of a novel immune checkpoint inhibitor on CRCs with deficient mismatch repair in a neoadjuvant setting in MSI-high patients [44]. The optimum adjuvant chemotherapy regimen for elderly patients with CRC should be elucidated in future studies. The MSI status has increased in importance as a promising biomarker, so now might be an ideal time to consider the routine investigation of MSI in CRCs and the expansion of insurance coverage after curative surgery.

In conclusion, RCCs showed a better CS-S in elderly patients ≥ 80 years old than LCCs. Although the MSI status was not investigated, the results suggest that MSI-high CRC, which is predominantly seen in the elderly and in RCCs, may affect survival outcomes. Further analyses, including assessments of molecular aberrations, are needed to identify the prognostic factors of CRCs in both the elderly and general populations.

References

Hori M, Matsuda T, Shibata A, Katanoda K, Sobue T, Nishimoto H, et al. Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2009: a study of 32 population-based cancer registries for the Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2015;45:884–91.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J cancer. 2015;134:E359–86.

Yamamoto S, Hinoi T, Niitsu H, Okajima M, Ide Y, Murata K, et al. Influence of previous abdominal surgery on surgical outcomes between laparoscopic and open surgery in elderly patients with colorectal cancer: subanalysis of a large multicenter study in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:695–704.

Hinoi T, Kawaguchi Y, Hattori M, Okajima M, Ohdan H, Yamamoto S, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients: a multicenter matched case-control study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2040–50.

Niitsu H, Hinoi T, Kawaguchi Y, Ohdan H, Hasegawa H, Suzuka I, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer is safe and has survival outcomes similar to those of open surgery in elderly patients with a poor performance status: subanalysis of a large multicenter case–control study in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:43–54.

Yamamoto S, Hinoi T, Niitsu H, Hattori M, Suzuka I, Fukunaga Y, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients: does history of abdominal surgery influence the surgical outcome? Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech. 2016;30:S250. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed17&NEWS=N&AN=72236161.

Adachi T, Hinoi T, Kinugawa Y, Enomoto T, Maruyama S, Hirose H, et al. Lower body mass index predicts worse cancer-specific prognosis in octogenarians with colorectal cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:779–87.

Okamura R, Hida K, Hasegawa S, Sakai Y, Hamada M, Yasui M, et al. Impact of intraoperative blood loss on morbidity and survival after radical surgery for colorectal cancer patients aged 80 years or older. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:327–34.

Takahashi M, Niitsu H, Sakamoto K, Hinoi T, Hattori M, Goto M, et al. Survival benefit of lymph node dissection in surgery for colon cancer in elderly patients: a multicenter propensity score-matched study in Japan. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2018;11:346–54.

Kochi M, Hinoi T, Niitsu H, Ohdan H, Konishi F, Kinugasa Y, et al. Risk factors for postoperative pneumonia in elderly patients with colorectal cancer: a sub-analysis of a large, multicenter, case-control study in Japan. Surg Today. 2018;48:756–64.

Holch JW, Ricard I, Stintzing S, Modest DP, Heinemann V. The relevance of primary tumour location in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of first-line clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2017;70:87–98.

Krajewska M, Kim H, Kim C, Kang H, Welsh K, Matsuzawa S, et al. Analysis of apoptosis protein expression in early-stage colorectal cancer suggests opportunities for new prognostic biomarkers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5451–61.

Burton S, Norman AR, Brown G, Abulafi AM, Swift RI. Predictive poor prognostic factors in colonic carcinoma. Surg Oncol. 2006;15:71–8.

Sinicrope FA, Rego RL, Foster N, Sargent DJ, Windschitl HE, Burgart LJ, et al. Microsatellite instability accounts for tumor site-related differences in clinicopathologic variables and prognosis in human colon cancers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2818–25.

Deschoolmeester V, Van Damme N, Baay M, Claes K, Van ME, Baert FJ, et al. Microsatellite instability in sporadic colon carcinomas has no independent prognostic value in a Belgian study population. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2288–95.

Wray CM, Ziogas A, Hinojosa MW, Le H, Stamos MJ, Zell JA. Tumor subsite location within the colon is prognostic for survival after colon cancer diagnosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1359–66.

Benedix F, Kube R, Meyer F, Schmidt U, Gastinger I, Lippert H. Comparison of 17,641 patients with right- and left-sided colon cancer: differences in epidemiology, perioperative course, histology, and survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:57–64.

Derwinger K, Gustavsson B. Variations in demography and prognosis by colon cancer location. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:2347–50.

Suttie SA, Shaikh I, Mullen R, Amin AI, Daniel T, Yalamarthi S. Outcome of right- and left-sided colonic and rectal cancer following surgical resection. Color Dis. 2011;13:884–9.

Weiss JM, Pfau PR, O’Connor ES, King J, LoConte N, Kennedy G, et al. Mortality by stage for right- versus left-sided colon cancer: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results-medicare data. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4401–9.

Ishihara S, Watanabe T, Akahane T, Shimada R, Horiuchi A, Shibuya H, et al. Tumor location is a prognostic factor in poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and signet-ring cell carcinoma of the colon. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:371–9.

Powell AGMT, Wallace R, Mckee RF, Anderson JH, Going JJ, Edwards J, et al. The relationship between tumour site, clinicopathological characteristics and cancer-specific survival in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. Color Dis. 2012;14:1493–9.

Bae JM, Kim JH, Cho NY, Kim TY, Kang GH. Prognostic implication of the CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancers depends on tumour location. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1004–12.

Yahagi M, Okabayashi K, Hasegawa H, Tsuruta M, Kitagawa Y. The worse prognosis of right-sided compared with left-sided colon cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:648–55.

Ishihara S, Murono K, Sasaki K, Yasuda K, Otani K, Nishikawa T, et al. Impact of primary tumor location on postoperative recurrence and subsequent prognosis in nonmetastatic colon cancers: a multicenter retrospective study using a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2018;267:917–21.

Jernvall P, Mäkinen MJ, Karttunen TJ, Mäkelä J, Vihko P. Microsatellite instability: impact on cancer progression in proximal and distal colorectal cancers. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:197–201.

Samowitz WS, Coleman LW, Leppert M, Curtin K, Ma KN, Slattery ML, et al. Microsatellite instability in sporadic colon cancer is associated with an improved prognosis at the population level. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:917–23.

Popat S, Hubner R, Houlston RS. Systematic review of microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:609–18.

Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, de Reynies A, Schlicker A, Soneson C, et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2015;21:1350–6.

Missiaglia E, Jacobs B, D’Ario G, Di Narzo AF, Soneson C, Budinska E, et al. Distal and proximal colon cancers differ in terms of molecular, pathological, and clinical features. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1995–2001.

Iacopetta B. Are there two sides to colorectal cancer? Int J Cancer. 2002;101:403–8.

Söreide K, Janssen EA, Söiland H, Körner H, Baak JP. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2006;93:395–406.

Halling KC, French AJ, McDonnell SK, Burgart LJ, Schaid DJ, Peterson BJ, et al. Microsatellite instability and 8p allelic imbalance in stage B2 and C colorectal cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1295–303.

Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–20.

Tougeron D, Mouillet G, Trouilloud I, Lecomte T, Coriat R, Aparicio T, et al. Efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer with microsatellite instability: a large multicenter AGEO study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv438.

Hong SP, Min BS, Kim TI, Cheon JH, Kim NK, Kim H, et al. The differential impact of microsatellite instability as a marker of prognosis and tumour response between colon cancer and rectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1235–43.

Kim CG, Ahn JB, Jung M, Beom SH, Kim C, Kim JH, et al. Effects of microsatellite instability on recurrence patterns and outcomes in colorectal cancers. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:25–33.

Kautto EA, Bonneville R, Miya J, Yu L, Krook MA, Reeser JW, et al. Performance evaluation for rapid detection of pan-cancer microsatellite instability with MANTIS. Oncotarget. 2017;8:7452–63.

Saltzstein SL, Behling CA. Age and time as factors in the left-to-right shift of the subsite of colorectal adenocarcinoma: a study of 213,383 cases from the California Cancer Registry. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:173–7.

Loree JM, Pereira AAL, Lam M, Willauer AN, Raghav K, Dasari A, et al. Classifying colorectal cancer by tumor location rather than sidedness highlights a continuum in mutation profiles and consensus molecular subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:1062–72.

Sanoff HK, Carpenter WR, Sturmer T, Goldberg RM, Martin CF, Fine JP, et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival of patients with stage III colon cancer diagnosed after age 75 years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2624–34.

Tournigand C, André T, Bonnetain F, Chibaudel B, Lledo G, Hickish T, et al. Adjuvant therapy with fluorouracil and oxaliplatin in stage II and elderly patients (between ages 70 and 75 years) with colon cancer: subgroup analyses of the multicenter international study of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin in the adjuvant treatment of colon cancer trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3353–60.

McCleary NJ, Meyerhardt JA, Green E, Yothers G, De Gramont A, Van Cutsem E, et al. Impact of age on the efficacy of newer adjuvant therapies in patients with stage II/III colon cancer: findings from the ACCENT database. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2600–6.

Cercek A, Lumish M, Sinopoli J, Weiss J, Shia J, Lamendola-Essel M, et al. PD-1 blockade in mismatch repair-deficient, locally advanced rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2201445.

Acknowledgements

We owe our deepest gratitude to the following members of the Japan Society of Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery for their cooperation: Eiji Kanehira, Kunihisa Shiozawa, Ageo Central General Hospital; Hiroyuki Bando, Daisuke Yamamoto, Ishikawa Prefectural Central Hospital; Seigo Kitano, Masafumi Inomata, Tomonori Akagi, Oita University; Junji Okuda, Keitaro Tanaka, Osaka Medical College; Masayoshi Yasui, Osaka National Hospital; Kosei Hirakawa, Kiyoshi Maeda, Osaka City University; Akiyoshi Kanazawa, Osaka Red Cross Hospital; Junichi Hasegawa, Junichi Nishimura, Osaka Rosai Hospital; Shintaro Akamoto, Kagawa University; Masashi Ueno, Hiroya Kuroyanagi, Cancer Institute Hospital; Masaki Naito, Kitasato University; Takashi Ueki, Kyushu University; Yoshiharu Sakai, Koya Hida, Yousuke Kinjo, Kyoto University; Yukihito Kokuba, Kyoto Prefectural University; Madoka Hamada, Kochi Health Sciences Center; Norio Saito, Masaaki Ito, National Cancer Hospital East; Shigeki Yamaguchi, Jou Tashiro, Saitama Medical University International Medical Center; Toshimasa Yatsuoka, Saitama Cancer Center; Tomohisa Furuhata, Kenji Okita, Sapporo Medical University; Yoshiro Kubo, Shi- koku Cancer Center; Shuji Saito, Yosuke Kinugasa, Shizuoka Cancer Center; Fumio Konishi, Saitama Medical Center Jichi Medical University; Kazuhiro Sakamoto, Michitoshi Goto, Juntendo University; Junichi Tanaka, Showa University Northern Yokohama Hospital; Nobuyoshi Miyajima, Tadashi Suda, Tsukasa Shimamura, St. Marianna University; Yoshihisa Saida, Toshiyuki Enomoto, Toho University Ohashi Medical Center; Takeshi Naito, Tohoku University; Yasuhiro Munakata, Ken Hayashi, Nagano Municipal Hospital; Yasukimi Takii, Satoshi Maruyama, Niigata Cancer Center Hospital; Yohei Kurose, Fukuyama City Hospital; Yasuhiro Miyake, Minoh City Hospital; Shoichi Hazama, Yamaguchi University; Shoich Fujii, Shigeru Yamagishi, Yokohama City University Medical Center; Masazumi Okajima, Hiroshima City Hiroshima Citizens Hospital; Seiichiro Yamamoto, National Cancer Center Hospital; Hisanaga Horie, Jichi Medical University; Kohei Murata, Suita Municipal Hospital; and Kenichi Sugihara, Tokyo Medical and Dental University Graduate School. This study was supported by the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Hiroshima University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

595_2024_2827_MOESM1_ESM.docx

The comparison of survival outcomes between right- and left-sided colorectal cancers by pathological stage II and III. The cancer-specific survival for stage II (A), cancer-specific relapse-free survival for stage II (B), cancerspecific survival for stage III (C), and cancer-specific relapse-free survival for stage III (D). The data were summarized as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values based on a log-rank test. Supplementary file1 (DOCX 181 KB)

595_2024_2827_MOESM2_ESM.docx

The comparison of the morbidities as postoperative complications in patients ≥80 years old between the open surgery and laparoscopic surgery groups for each type of CRC. Supplementary file2 (DOCX 47 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sada, H., Hinoi, T., Niitsu, H. et al. Right-sided versus left-sided colorectal cancer in elderly patients: a sub-analysis of a large multicenter case–control study in Japan. Surg Today (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-024-02827-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-024-02827-9