Abstract

Purpose

Treatment success can be defined by asking a patient how they perceive their condition compared to prior to treatment, but it can also be defined by establishing success criteria in advance. We evaluated treatment outcome expectations in patients undergoing surgery or non-operative treatment for cervical radiculopathy.

Methods

The first 100 consecutive patients from an ongoing randomized controlled trial (NCT03674619) comparing the effectiveness of surgical and nonsurgical treatment for cervical radiculopathy were included. Patient-reported outcome measures and expected outcome and improvement were obtained before treatment. We compared these with previously published cut-off values for success. Arm pain, neck pain and headache were measured by a numeric rating scale. Neck disability index (NDI) was used to record pain-related disability. We applied Wilcoxon signed-rank test to compare the expected outcome scores for the two treatments.

Results

Patients reported mean NDI of 42.2 (95% CI 39.6–44.7) at baseline. The expected mean NDI one year after the treatment was 4 (95% CI 3.0–5.1). The expected mean reduction in NDI was 38.3 (95% CI 35.8–40.8). Calculated as a percentage change score, the patients expected a mean reduction of 91.2% (95% CI 89.2–93.2). Patient expectations were higher regarding surgical treatment for arm pain, neck pain and working ability, P < 0.001, but not for headache.

Conclusions

The expected improvement after treatment of cervical radiculopathy was much higher than the previously reported cut-off values for success. Patients with cervical radiculopathy had higher expectations to surgical treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neck pain is among the leading causes of years lived with disability worldwide [1]. Cervical radiculopathy usually involves both neck pain and arm pain. Two systematic reviews have found no clear benefits of surgery over nonsurgical treatments [2, 3]. Actually, one review indicated that cervical radiculopathy is a self-limiting condition in most cases [4].

Patient expectations might be important for post-treatment outcomes and satisfaction [5,6,7]. Satisfaction is not necessarily equivalent to fulfilled expectations [8]. However, having one’s expectations fulfilled alone was the most significant predictor of a good outcome for patients undergoing lumbar decompression surgery [9].

In assessing the success rate after treatment, the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) is generally used as a guideline. The estimate of MCID focuses on patient’s perception of benefit alone. A single question is used to rate the perception of change after treatment. The validity of the anchor is rarely questioned despite that it represents the retrospective perception of global change, often ranging from completely recovered to worse. This method has been criticized as being “tautological” because one subjective measure is validated by another subjective measure [10, 11]. MCID was originally defined as “the smallest difference in score in domain of interest which patients perceive as beneficial and which would mandate, in the absence of troublesome side effects and excessive cost, a change in patient´s management” [12]. The wording was later revised and replaced by minimal important difference (MID) [13, 14]. Later research has focused on the difference between those who rate themselves as slightly improved compared to unchanged. The benefit, side effects, costs and change in health care utilization, or continued drug consumption that can be measured objectively are not incorporated in the anchor [15]. In an editorial from 2010, Eugene Carragee predicted that the anchor-based method would be a historical oddity, like a success rate based on the surgeon’s impression of his own good work [10]. In contrast, the literature in this field reflects an opposite trend.

The concept of success has been aligned to an improvement that reflects a substantial amount of change rather than minimal change [16, 17]. Success may simply be defined as the achievement of a desired result, meeting a defined range of expectations [18, 19]. A recent study, based on the data from the Norwegian Registry for Spine Surgery (NORspine), found 13.5 points change on NDI as a criteria for success after surgery for cervical radiculopathy [20]. The criteria for success were obtained as the patient perceived benefit of an operation by asking the patient at follow-up using global perceived effect scale (GPE) as an anchor [20]. Similarly, the benefit of the treatment can be explored by defining the criteria for success through the improvement a patient expects apriori.

The improvement a patient expects in order to undergo surgery or non-operative treatment for cervical radiculopathy has to our knowledge not been examined. Therefore, we wanted to evaluate treatment outcome expectations by asking the patients to fill in their expected improvement at baseline and compare these with previously published cut-off values for success.

Methods

Study population

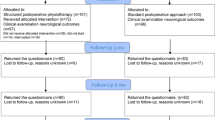

This is a cross-sectional study. This report is consistent with the Strengthening The Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [21]. The first 100 consecutive patients from an ongoing randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of surgical and nonsurgical treatment for cervical radiculopathy were included [22]. The aim of this study was to compare treatment outcome expectations with established cut-off values for success. We did not compare the treatment outcome expectations with the actual outcome at one year because reported expectations were derived from the ongoing clinical trial. The study participants were outpatient clinic patients referred to Oslo University Hospital for treatment of cervical radiculopathy consistent with disc herniation or spondylosis at levels C5/C6 and/or C6/C7 between October 2018 and August 2020. Demographics and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were obtained at the baseline before treatment and before patients were allocated to either surgery or conservative treatment. All scores were filled in by the patient with no involvement of the authors. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The trial was approved by the Norwegian ethics committee, REK 2017/2125, and registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov—as NCT03674619—on September 17, 2018.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged 20–65 years

-

Study 1 Neck and arm pain for at least 3 months, and a corresponding herniation involving one cervical nerve root (C6 or C7)

Study 2 Neck and arm pain for at least 3 months, with corresponding spondylosis involving C6 and/or C7

-

Arm pain intensity of at least 4 on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain)

-

Willing to accept randomisation to either of the treatment alternatives

-

Neck disability index (NDI) > 30%

Exclusion criteria

Patients with any previous cervical fractures or cervical spine surgery; signs of myelopathy; rapidly progressive paresis or paresis < grade 4; pregnancy; arthritis involving the cervical spine; infection or active cancer; generalized pain syndrome; serious psychiatric or somatic disease that excludes one of the treatment alternatives; concomitant shoulder disorders that may interfere with the outcome; abuse of medication/narcotics; inability to understand written Norwegian; and unwillingness to accept one of the treatment alternatives.

Outcome measures

The Neck Disability Index consists of ten questions about pain-related disability, including items such as headaches, concentration problems, reading issues and sleep disturbances. Each item is rated on a 6-point scale from 0 (no disability) to 5 (full disability). The numeric response for each item is summed for a score varying from 0 to 50 and then transformed into a total score ranging from 0 to 100% (higher scores representing more severe symptoms). The Norwegian version has been validated in patients with neck pain and with cervical radiculopathy [23, 24].

Arm pain, measured by a numeric rating scale (NRS) from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain) [25].

Neck pain, measured by a numeric rating scale (NRS) from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain) [25].

Patient expectations ahead of treatment. The patients were asked to fill out the Neck Disability Index—imagining that they were at one year post-treatment—and to select the lowest category (poorest result) they would be content with for each item. This is the written instruction that was given: “We will now ask about your expectations. Imagine that it’s been one year since you were included in the study and that you are satisfied. Please tick off one box for each of the following ten questions. For each question choose the one category that you can be satisfied with.”

The patients were also asked to answer a Global Score about what they expect their symptoms to be like one year post-treatment (ranging from much worse to much better) [26]. This was registered separately for arm pain, neck pain, headaches and ability to work. The seven response options were much worse, worse, slightly worse, unchanged, slightly better, better, and much better. We asked the patients to report what they would expect in case they received the surgical versus the nonsurgical treatment.

Fear-avoidance beliefs, evaluated using the Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) [27,28,29].

Emotional distress assessed by the 10-question version of the Hopkins Symptom Check List (HSCL-10) [30].

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as means with standard deviation (SD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), or median with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical data are presented as numbers (n) and percentages (%). We applied Wilcoxon signed-rank test to compare the expected outcome scores for the two treatments. Expected NDI percentage change was calculated by subtracting expected NDI score from baseline NDI score divided by baseline NDI score and multiplied by 100. All the statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS (version 26) statistical package. A P value < 0.01 was set as the level of statistical significance.

Out of the 100 patients included in this study, one failed to complete the expected NDI and was excluded from the analyses. Another nine patients misinterpreted the expected NDI questionnaire. They thought they were asked about the symptoms at the present time point rather than symptoms one year ahead in time. These patients scored almost identically for NDI and for expected NDI in one year. We cross-checked their expectations for arm pain, neck pain, headaches and working ability, and they expected almost no pain and much better working ability one year ahead in time. After a discussion within the study group, these patients were excluded from the analyses.

Results

The study population comprised of 53 females and 47 males aged from 29 to 63 years. 20% were daily smokers, 69% were married or cohabitants, 58% used painkillers daily, 44% were sick-listed 50% or more. Median duration of arm pain was 7.7 months (Table 1).

Patients reported mean NDI of 42.2 (95% CI 39.6 to 44.7) at baseline. Mean reported arm pain at baseline was 6.1 (95% CI 5.7–6.5) measured by NRS (Table 2).

The expected mean NDI one year after the treatment was 4 (95% CI 3.0–5.1). The expected mean reduction in NDI was 38.3 (95% CI 35.8–40.8). Calculated as a percentage change score, the patients expected a mean reduction of 91.2% (95% CI 89.2–93.2) (Table 2).

Patient expectations were higher for surgical treatment for arm pain, neck pain and working ability, P < 0.001 (Fig. 1). For expected headache in one year, there was no significant difference in expected scores, P = 0.537.

Discussion

Neck Disability Index (NDI) is a frequently used patient-reported outcome measure in cervical radiculopathy. The score ranges from 0 to 100, and the higher the score, the worse the pain and disability. A systematic review reported minimal important difference (MID) to vary from 10 to 38 [31]. A cohort study of patients who underwent a cervical fusion for degenerative spine conditions calculated MID of 15 and substantial clinical benefit (SCB) of 20 [15]. A difference of 10 is most commonly used for sample size calculation in trials comparing various surgical procedures for cervical radiculopathy [32].

Compared to the previously reported criteria for success for Norwegian patients undergoing anterior cervical decompression and fusion for cervical radiculopathy, our patients have much greater expectations for success [20]. Figure 2 shows that almost all of our patients, in order to be satisfied, expect a higher improvement than the proposed criteria of 13.5 NDI points.

Expected NDI change score. The expected mean reduction in NDI one year after the treatment was 38.3 (95% CI 35.8–40.8). For comparison, 13.5 points change on NDI (red line) as the proposed criteria for success after surgery for cervical radiculopathy [20]

Figure 3 demarcates the gap between the expected improvement observed and the previously reported criteria for success that were described as of particular importance in distinguishing between a successful outcome or not. NDI percentage change score of 35% or more was thought to be a highly sensitive cut-off value for success in the study by Mjåset et al., but in our study, the patients expect that NDI improves 91% after treatment for cervical radiculopathy [20].

Expected NDI percentage change score. The patients expected a mean reduction in NDI of 91.2% (95% CI 89.2–93.2). For comparison, 35% change in NDI (red line) as the proposed criteria for success after surgery for cervical radiculopathy [20]

Compared to NDI percentage change in other interventional studies, the expected improvement remains relatively high. Reported mean NDI after treatment varies between 21 and 28, representing a percentage change of 30–60%, depending on the baseline score [32,33,34,35].

We estimated the patients’ expectation of an outcome. By doing this, we simulated scoring the desired result. When the expectation score is achieved after treatment, the aim is fulfilled and outcome may be regarded as a success. By using this method, the lower level of the 95% confidence interval for the expected outcome was 35.8 on the NDI as compared with 13.5 in a recent study on criteria for success after surgery for cervical radiculopathy [20]. The corresponding lower level of percentage improvement was 89.2% compared with 35% [20]. This observed major discrepancy questions the use of MID as success criteria for spine surgery [36, 37]. In a more recent systematic review, Copay et al. consider MID values that are lower than the measurement error or minimal detectable difference (MDC) as problematic and debates the concept of MID [38, 39]. We agree that it is questionable to report that a reduction from 10/10 to 8/10 on VAS is a success, even to 7/10 which is more according to a 30% improvement suggested in many studies [37]. The interpretation has many aspects because the scales are statistically treated as linear, while an improvement from 5/10 to 3/10 is likely to be different from an improvement from 10/10 to 8/10. More importantly, we must take into consideration side effects, costs and change in health care utilization and continued drug consumption when discussing whether a treatment was successful.

MID is defined and estimated in a variety of ways in the literature, and there is a lack of formal agreement on which methods that are superior [38, 39]. The validity of using a subjective anchor to estimate success after treatment may be questioned because of bias and estimate error of the anchor. Likewise, we assume that it is difficult for the patient to score their expected NDI one year post treatment. Nevertheless, both ways of estimating success may be within the definition of the term. The measurement error is the minimal difference that reliably can be estimated in an individual patient. When MID or success rate is used in a shared decision with the patient before treatment, we also have to consider the individual measurement error of an outcome in order to inform the patient about the expected outcome.

Limitations and strengths of the study

The main limitation of this study is the use of a non-validated method to explore the patient expectations. Although the NDI itself is validated in Norwegian patients with cervical radiculopathy, the question about expectations to treatment is not validated. We did not change the NDI in any way. In this study, we emphasised that the following questions were related to patient expectations and not the present situation. This proved to be insufficient in 9% of the participants, as they obviously did not pay attention to the introduction and answered the questions in the same matter they did with the baseline NDI. Asking patients about their expectations to treatment is not straight forward. There is always uncertainty related to how an individual interprets the question. Are they telling us about their realistic expectations, minimal expectations or perhaps their hopes? Even though all patients were provided with balanced information prior to inclusion and randomization in the study, these are surgical patients referred to neck surgery. Patients were informed that the two treatments are both very good and probably equally effective. One cannot exclude that this led to higher expectations regardless of treatment. Regarding the outcome after surgery, we applied the results from a recent multicenter RCT where our hospital contributed with most patients [32]. This trial compared the efficacy of an artificial disc with the traditional surgical method used in the present study. Furthermore, we applied the results from a systematic review concluding that there is sparse evidence to conclude that the efficacy of surgery is superior to conservative treatment [3]. By informing the patients in this way, we used the existing evidence but because the definition of success is debated, we might have been too optimistic in informing the patients. On the other hand, our information adds to all the other information the patients had received preceding inclusion in the present study. All scores were filled in by the patient with no involvement of the authors. Having in mind that having one’s expectations fulfilled alone was the most significant predictor of a good outcome for patients undergoing lumbar decompression surgery [9], one must not underestimate the importance of patient expectations. It would be interesting to compare the expected outcome with actual outcome scores at one year. However, the data were derived from an ongoing RCT. The author of the current paper and the statistician are blinded to treatment allocation. We chose not to extract the primary outcome data until the end of trial. This is in line with good reporting practice and the CONSORT recommendations [40]. Patients in this study come from Health Region South-East in Norway covering a population of about 2.9 million inhabitants. That constitutes the majority of patients registered in the (NORspine), so these patients are in fact very similar to the ones used in the recent study on criteria for success after surgery for cervical radiculopathy [20].

We were surprised to find that so many patients expected complete or almost complete relief, but the instructions in filling out the questionnaire were very clear and we actually asked them to fill in the lowest value they would accept to be satisfied with the treatment outcome. A validation using qualitative methods interviewing a randomly selected group of patients would have been interesting but this is rarely conducted in studies using the retrospective anchor method and was considered to be out of the scope of the present study.

Some of the strengths of this study are that we had a relatively large and homogenous group of patients who had undergone thorough evaluation by a neurosurgeon and a specialist in physical medicine and rehabilitation. They reported a high level of pain and disability at baseline all measured by validated tools; NRS for arm pain, neck pain and headache, and NDI for pain-related disability.

Conclusions

The mean expectation of about 90% improvement on the primary outcome as observed in this study suggests that a level of 30% improvement is critically low as a definition of success. Future studies using both qualitative and quantitative methods are warranted to explore this field. This is important because readers, researchers and stakeholders often interpret the success as a substantial improvement as different from or at worst slightly above the measurement error.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M et al (2012) Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380:2163–2196. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2

Nikolaidis I, Fouyas IP, Sandercock PA, Statham PF (2010) Surgery for cervical radiculopathy or myelopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001466.pub3

van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Ostelo R, van Tulder MW, Peul W, Koes BW et al (2013) Surgery versus conservative care for neck pain: a systematic review. Eur Spine J 22:87–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-012-2553-z

Iyer S, Kim HJ (2016) Cervical radiculopathy. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 9:272–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-016-9349-4

Barron CJ, Moffett JA, Potter M (2007) Patient expectations of physiotherapy: definitions, concepts, and theories. Physiother Theory Pract 23:37–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593980601147843

Mondloch MV, Cole DC, Frank JW (2001) Does how you do depend on how you think you’ll do? A systematic review of the evidence for a relation between patients’ recovery expectations and health outcomes. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J 165:174–179

Mahomed NN, Liang MH, Cook EF, Daltroy LH, Fortin PR, Fossel AH et al (2002) The importance of patient expectations in predicting functional outcomes after total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol 29:1273–1279

Nilsdotter AK, Toksvig-Larsen S, Roos EM (2009) Knee arthroplasty: are patients’ expectations fulfilled? A prospective study of pain and function in 102 patients with 5-year follow-up. Acta Orthop 80:55–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453670902805007

Mannion AF, Junge A, Elfering A, Dvorak J, Porchet F, Grob D (2009) Great expectations: really the novel predictor of outcome after spinal surgery? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34:1590–1599. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31819fcd52

Carragee EJ (2010) The rise and fall of the “minimum clinically important difference.” Spine J 10:283–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2010.02.013

Gatchel RJ, Mayer TG (2010) Testing minimal clinically important difference: additional comments and scientific reality testing. Spine J 10:330–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2010.01.019

Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH (1989) Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials 10:407–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6

Schünemann HJ, Guyatt GH (2005) Commentary–goodbye M(C)ID! Hello MID, where do you come from? Health Serv Res 40:593–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00374.x

Devji T, Carrasco-Labra A, Qasim A, Phillips M, Johnston BC, Devasenapathy N et al (2020) Evaluating the credibility of anchor based estimates of minimal important differences for patient reported outcomes: instrument development and reliability study. BMJ 369:m1714. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1714

Carreon LYMDM, Glassman SDMD, Campbell MJMD, Anderson PAMD (2010) Neck Disability Index, short form-36 physical component summary, and pain scales for neck and arm pain: the minimum clinically important difference and substantial clinical benefit after cervical spine fusion. Spine J 10:469–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2010.02.007

Solberg T, Johnsen LG, Nygaard OP, Grotle M (2013) Can we define success criteria for lumbar disc surgery? Estimates for a substantial amount of improvement in core outcome measures. Acta Orthop 84:196–201. https://doi.org/10.3109/17453674.2013.786634

Glassman SD, Copay AG, Berven SH, Polly DW, Subach BR, Carreon LY (2008) Defining substantial clinical benefit following lumbar spine arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90:1839–1847. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.G.01095

Wikipedia tfe (2021) Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Success_(concept). Accessed 14 April 2021

Press CU (2021) Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/success. Accessed 14 April 2021

Mjaset C, Zwart JA, Goedmakers CMW, Smith TR, Solberg TK, Grotle M (2020) Criteria for success after surgery for cervical radiculopathy-estimates for a substantial amount of improvement in core outcome measures. Spine J 20:1413–1421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2020.05.549

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP (2008) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61:344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

Taso M, Sommernes JH, Kolstad F, Sundseth J, Bjorland S, Pripp AH et al (2020) A randomised controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of surgical and nonsurgical treatment for cervical radiculopathy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21:171. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-3188-6

Johansen JB, Andelic N, Bakke E, Holter EB, Mengshoel AM, Roe C (2013) Measurement properties of the norwegian version of the neck disability index in chronic neck pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 38:851–856. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31827fc3e9

Sundseth J, Kolstad F, Johnsen LG, Pripp AH, Nygaard OP, Andresen H et al (2015) The neck disability index (NDI) and its correlation with quality of life and mental health measures among patients with single-level cervical disc disease scheduled for surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 157:1807–1812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-015-2534-1

Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, Wright V, Branco JA, Anderson JA (1978) Studies with pain rating scales. Ann Rheum Dis 37:378–381. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.37.4.378

Grovle L, Haugen AJ, Hasvik E, Natvig B, Brox JI, Grotle M (2014) Patients’ ratings of global perceived change during 2 years were strongly influenced by the current health status. J Clin Epidemiol 67:508–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.001

Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ (1993) A fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and diasability. Pain 52:157–168

Dedering A, Borjesson T (2013) Assessing fear-avoidance beliefs in patients with cervical radiculopathy. Physiother Res Int 18:193–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.1545

Grotle M, Vollestad NK, Veierod MB, Brox JI (2004) Fear-avoidance beliefs and distress in relation to disability in acute and chronic low back pain. Pain 112:343–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.020

Strand BH, Dalgard OS, Tambs K, Rognerud M (2003) Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: a comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI-5 (SF-36). Nord J Psychiatry 57:113–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480310000932

MacDermid JC, Walton DM, Avery S, Blanchard A, Etruw E, McAlpine C et al (2009) Measurement properties of the neck disability index: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 39:400–417. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2009.2930

Sundseth J, Fredriksli OA, Kolstad F, Johnsen LG, Pripp AH, Andresen H et al (2017) The Norwegian Cervical Arthroplasty Trial (NORCAT): 2-year clinical outcome after single-level cervical arthroplasty versus fusion-a prospective, single-blinded, randomized, controlled multicenter study. Eur Spine J 26:1225–1235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4922-5

Kuijper B, Tans JT, Beelen A, Nollet F, de Visser M (2009) Cervical collar or physiotherapy versus wait and see policy for recent onset cervical radiculopathy: randomised trial. BMJ 339:b3883. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b3883

Dedering A, Peolsson A, Cleland JA, Halvorsen M, Svensson MA, Kierkegaard M (2018) The effects of neck-specific training versus prescribed physical activity on pain and disability in patients with cervical radiculopathy: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 99:2447–2456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.06.008

Engquist M, Löfgren H, Öberg B, Holtz A, Peolsson A, Söderlund A et al (2013) Surgery versus nonsurgical treatment of cervical radiculopathy: a prospective, randomized study comparing surgery plus physiotherapy with physiotherapy alone with a 2-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 38:1715–1722. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31829ff095

Hermansen E, Myklebust TA, Austevoll IM, Rekeland F, Solberg T, Storheim K et al (2019) Clinical outcome after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in patients with insignificant lower extremity pain. A prospective cohort study from the Norwegian registry for spine surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 20:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2407-5

Austevoll IM, Gjestad R, Grotle M, Solberg T, Brox JI, Hermansen E et al (2019) Follow-up score, change score or percentage change score for determining clinical important outcome following surgery? An observational study from the Norwegian registry for Spine surgery evaluating patient reported outcome measures in lumbar spinal stenosis and lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 20:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-2386-y

Copay AG, Chung AS, Eyberg B, Olmscheid N, Chutkan N, Spangehl MJ (2018) Minimum clinically important difference: current trends in the orthopaedic literature, part I. JBJS Rev 6:e1. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.RVW.17.00159

Copay AG, Eyberg B, Chung AS, Zurcher KS, Chutkan N, Spangehl MJ (2018) Minimum clinically important difference: current trends in the orthopaedic literature, part II. JBJS Rev 6:e2. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.RVW.17.00160

The L (2010) CONSORT 2010. The Lancet 375:1136. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60456-4

Acknowledgements

When designing this trial, we discussed several issues with the former leader of the Norwegian Patient Organization for Spinal Pain. We are grateful for their feedback on this manuscript. We thank the secretaries at Department of Neurosurgery and Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. We would also like to thank all the patients participating in the project.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital). The authors are grateful to the Southern and Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority for funding this study. The sponsor had no role in designing this trial, writing the manuscript, or in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors listed have contributed sufficiently to the project to be included as authors, and all those who are qualified to be authors are listed in the author by-line. JIB had the original idea for this study and secured funding. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MT. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and stand by the integrity of the entire work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

The trial was approved by the Norwegian ethics committee, REK 2017/2125.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taso, M., Sommernes, J.H., Bjorland, S. et al. What is success of treatment? Expected outcome scores in cervical radiculopathy patients were much higher than the previously reported cut-off values for success. Eur Spine J 31, 2761–2768 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-022-07234-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-022-07234-7