Abstract

Purpose

To determine the content of current Dutch expert hospital physiotherapy practice for patients undergoing lumbar spinal fusion (LSF), to gain insight into expert-based clinical practice.

Methods

At each hospital where LSF is performed, one expert physiotherapist received an e-mailed questionnaire, about pre- and postoperative physiotherapy and discharge after LSF. The level of uniformity in goals and interventions was graded on a scale from no uniformity (50–60 %) to very strong uniformity (91–100 %).

Results

LSF was performed at 34 of the 67 contacted hospitals. From those 34 hospitals, 28 (82 %) expert physiotherapists completed the survey. Twenty-one percent of the respondents saw patients preoperatively, generally to provide information. Stated postoperative goals and administered interventions focused mainly on performing transfers safely and keeping the patient informed. Outcome measures were scarcely used. There was no uniformity regarding advice on the activities of daily living.

Conclusion

Dutch perioperative expert physiotherapy for patients undergoing LSF is variable and lacks structural outcome assessment. Studies evaluating the effectiveness of best-practice physiotherapy are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the past decades surgical interventions, especially lumbar spinal fusion (LSF), have gained popularity [1]. In the United States the number of LSFs increased between 1998 and 2007 by 237 % (from 174,223 to 413,171 procedures) [2]. LSF is a procedure in which two or more vertebrae are fixated to restrict painful spinal motion.

Regaining function after LSF is very important for the patient. Clinical rehabilitation, in particular physiotherapy, may be an important factor in regaining functional independence. There is little knowledge on the optimal physiotherapy practice in patients undergoing LSF. In a systematic review of the literature, Rushton et al. [3] demonstrated that studies on the effectiveness of physiotherapy after LSF are of low quality and too heterogeneous to pool. Consequently, physiotherapists have to depend on their own competence and experience in their day-to-day practice. This results in highly variable clinical care with unknown effectiveness, as demonstrated by Rushton et al. [4] in the UK. Thus, best clinical physiotherapy practice in LSF remains to be elucidated [3, 5].

We hypothesised that studying clinical practice for patients undergoing LSF provided by expert physiotherapists would establish a better understanding of the current best practice. These data could serve as temporary guidelines for hospital physiotherapists working with people undergoing LSF and as a usual care arm in future randomised studies. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to describe the content of Dutch inpatient expert physiotherapy before and after LSF.

Methods

Design and population

In this cross-sectional survey study, we asked expert physiotherapists who perform inpatient treatment before and after LSF to complete a survey on their practice routines. To select the expert physiotherapists, we contacted all heads of physiotherapy departments who were registered with the Dutch Association for Physiotherapy in Hospitals (NVZF) by e-mail (02/06/2014). The NVZF represents 67 general hospitals, academic hospitals and specialised care centres in the Netherlands [6]. Hospitals where LSF was not performed were excluded. Department heads were informed about the content of the study and were asked to forward the survey to their expert physiotherapist concerning LSF (i.e. the physiotherapist they would want to be treated by if they underwent LSF). Return of the questionnaire was considered as informed consent. A reminder was sent after 1 month. This manuscript is reported according to the STROBE guideline for cross-sectional studies [7] and the CHERRIES checklist for reporting the results of internet E-surveys [8]. Assessment by a medical ethics review board was not necessary.

Survey

The survey comprised 46 questions (nine open and 37 multiple-choice) on four domains: (1) demographic data (nine questions), (2) preoperative diagnostics and treatment (seven questions), (3) postoperative diagnostics and treatment (26 questions), and (4) information for discharge (four questions). The questions in the survey were based on a similar study in the UK by Rushton et al. [4]. However, we adapted the survey to the Dutch healthcare context. Moreover, we based the answer options for the questions on diagnostic procedures on the ICF core set for LBP [9]. Finally, we added 17 questions in order to obtain information regarding multidisciplinary cooperation, discharge criteria and referral information after discharge. The survey (translated into English; i.e., not an official cross-cultural adaptation) is available as an appendix to this manuscript.

Data collection

To collect the data, we used Qualtrics (http://www.qualtrics.com), a commonly used internet-based program for administering surveys [10]. To minimise the chance of incomplete responses due to skipped and/or forgotten questions, the function “Force Response” was used. “Skip Logic” was added to increase the efficiency of the questionnaire (completion time was approximately 15 min). Respondents were able to review and change their given answers using a back button. To prevent multiple answers from the same individual we checked from which hospital the questionnaire originated and their IP-address. In the case of duplicate entries, only the first entry was kept for analysis. The IP-addresses were deleted before the data was analysed. The questionnaire was pre-tested by five peers.

Data analysis

First of all, two researchers (ES and EJ) categorised the answers of the open questions and labelled them. Differences in categories between the two assessors were resolved by a third researcher (TH). In case of disagreement, the respondent was re-approached for further clarification. All data was analysed anonymously and presented as such. Completeness of the questionnaire was checked; forms were not included in the analysis if over 50 % of the data was missing.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study population and the survey answers [i.e. numbers and percentages, means and standard deviations (SD), and medians and interquartile ranges (IQR)]. To determine the level of uniformity between the physiotherapists on relevant goals and interventions used in expert standard practice, we used categories ranging from No uniformity to Very strong uniformity (see Table 1). Uniformity shows the percentage of participants choosing one answer option (per question). The more participants choosing one answer option, the higher the level of uniformity for a specific goal or intervention.

Results

A total of 67 expert physiotherapists in 67 different hospitals were approached to participate in this study. In 33 of the hospitals LSF surgery was not performed and they were therefore excluded from the study. Of the resulting 34 respondents, 29 (85 %) responded to our survey. One survey was excluded from the analysis due to missing data. Thus, a total of 28 questionnaires (82 % of eligible respondents) were included in the analysis. Figure 1 shows the number of respondents at each stage of the study. Table 2 provides information concerning the respondents’ demographics.

Preoperative physiotherapy

The majority of the respondents, representing 22 hospitals (79 %), did not provide preoperative physiotherapy care for patients undergoing LSF. In the six cases where preoperative care was provided, it was mainly group-based (five respondents) and aimed at informing the patient about the postoperative phase (six respondents). Regarding preoperative diagnostics and instructions there was no uniformity or low uniformity in goals and interventions such as performing a preoperative functional assessment (67 %), instructing patients on how to perform postoperative transfers (50 %) or taking a history (67 %) (see Table 3).

Postoperative inpatient physiotherapy

Inpatient physiotherapy for patients recovering from LSF was standard care in 22 hospitals (79 %). In four (14 %) cases, patient-specific needs were first assessed to establish the necessity of inpatient physiotherapy. In the remaining two cases it was unclear how physiotherapy was initiated and under which circumstances it was provided. Commonly, patients were treated once (50 %) or twice (34 %) a day by a physiotherapist for an average (SD) of 3.8 (1.3) days and a median (IQR) of 20 (18–25) min per session. In the majority of the hospitals (61 %) mono-disciplinary care was provided (i.e., by the physiotherapist). In the case where multidisciplinary treatment was reported in hospitals, the other professions most frequently involved were: family caregivers (11 %), nurses (11 %), and occupational therapists (7 %).

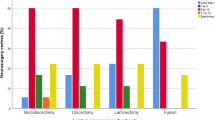

Respondents agreed to a great extent on the goals and interventions that are part of the inpatient rehabilitation process after LSF surgery (Table 4). Postoperative goals with strong to very strong uniformity were: getting the patient to function safely (93 %), getting the patient out of bed (93 %), informing the patient on the rehabilitation process (93 %), getting the patient to walk (96 %) with an optimal gait pattern (93 %), getting the patient to climb stairs (89 %) and getting the patient to carry out (bed) transfers (89 %). Postoperative interventions with very strong uniformity were: getting out of bed (93 %), walking (96 %) and climbing stairs (93 %). Interventions with strong uniformity were: taking patient history (86 %), giving advice on functional activities and restrictions (89 %), instructing and training patients about transfers (89 %), answering questions (89 %) and giving instructions for exercises at home (82 %).

No uniformity or low uniformity among respondents was seen for several goals and interventions, including: performing a physical examination (57 %), instructing how to lift and carry objects (32 %), and instructing how to use the restroom (32 %). Moreover, there was no uniformity regarding when to resume the activities of daily life after discharge (Table 5). Finally, a minority of respondents used questionnaires (4 %) or observational measurements (18 %) to guide or evaluate their therapy during the inpatient rehabilitation.

Discharge information

Of the responding physiotherapists 32 % always referred patients for outpatient physiotherapy and 50 % only if deemed necessary. Typically, according to the respondents, the decision to refer depends on the patient’s physical capacity, coping ability or on the physician’s advice. Our respondents stated that the majority of patients are discharged to their home with a referral to primary care physiotherapy (78 %). At which practice the rehabilitation process after discharge is continued is mainly decided by the patient (67 %) and primarily based on the distance from their house to the practice (67 %).

Discussion

This study assessed current inpatient treatment before and after LSF surgery in Dutch hospitals from the perspective of expert physiotherapists. We established that preoperative physiotherapy is uncommon and mainly limited to providing information on postoperative rehabilitation. Inpatient postoperative physiotherapy is common after LSF surgery and in most cases a standard procedure. Physiotherapists primarily aim to help patients to function safely (i.e., get out of bed, get into a chair, walk and climb stairs) by practicing functional activities (typically after an anamnesis) and providing information. Questionnaires and performance measures were scarcely used, and there was no uniformity among physiotherapists concerning giving advice on resuming the activities of daily life. Outpatient care is prescribed mainly if deemed necessary by the hospital physiotherapist.

Strengths and limitations

A number of strengths and weaknesses are apparent in this study. The strengths include the validity of our findings regarding the Dutch inpatient physiotherapy practice, as 74 % (67 out of 91) of the Dutch hospitals [6] were approached with a response rate of 93 %. Furthermore, we focused only on expert physiotherapists, allowing an overview of expert based care as reported both before and after LSF. We believe we were successful in doing so, as the majority of physiotherapists had 8 or more years of experience treating patients undergoing LSF.

Some limitations include the external validity of our findings. After all, the data might not be generalisable to some other countries due to differences in cross-cultural health care, educational systems and curricula, although the findings might be relevant to other European countries due to their similarities in culture and healthcare systems. Furthermore, questionnaires rely on self-reported data and therefore do not guarantee an accurate reflection of daily clinical practice. Ideally, observations of clinical practice would be performed; however, due to time and budgetary constraints, this method was not feasible. Finally, we aimed to include expert physiotherapists through asking the department heads to select the therapist who they would want to be treated by after an LSF procedure. A better method for selecting experts would be based on their clinical outcomes; unfortunately this data is not available [11].

Comparison to the literature

There is just one other study that describes the current practice of physiotherapy for patients undergoing LSF [4]. This study investigated physiotherapy practice for patients undergoing LSF in the UK [4]. The authors administered a nationwide survey, targeting all physiotherapists that were involved in the management of patients before or after LSF within the UK National Health Service trusts. Our findings overlap considerably with theirs. For instance, in both the UK and the Netherlands: (a) physiotherapy care is provided structurally after surgery (70 vs. 79 %, respectively); (b) few centres used questionnaires and performance measures to evaluate or monitor the treatment (6 and 19 vs. 4 and 18 %, respectively); and (c) interventions such as providing information (98 vs. 89 %, respectively), answering questions (95 vs. 89 %, respectively), and instructing and supervising walking (98 vs. 96 %, respectively) were most common.

A notable difference between practice in the Netherlands and the UK is the use of therapeutic protocols; 49 % in the UK and 82 % in the Netherlands. In the Netherlands it is common for hospital physiotherapists to protocolise their postoperative care [12]. Through the use of protocols, physiotherapists who are unfamiliar with working practices in other departments, can still deliver care as best as possible. Unfortunately, these protocols carry the risk that all therapists will deliver protocolised and therapist centred (one-size-fits-all) care instead of the currently favoured patient centred and personalised care [13, 14], as demonstrated by the high number of expert therapists using protocols to guide their day-to-day practice therapy in our study. We specifically included expert physiotherapists in our survey population to distil best (physiotherapy) practice in LSF [13, 14]. Interestingly, we found that factors essential for clinical reasoning (such as functional diagnosis) were often not evaluated, therapy was either never or always provided (regardless of the patient’s need), and therapy was typically delivered on time-based principles (not goal-based). It seems that now is the time for best practice guidelines to be established.

General findings

In the Netherlands it may be necessary to reconsider the approach of the (expert) hospital physiotherapist in the management of individuals undergoing LSF. Considering that: (1) there is a (small) number of hospitals where LSF surgery is routinely performed without involving physiotherapists in the clinical care pathway, possibly due to the lack of evidence on benefits of clinical physiotherapy after lumbar surgery [14]; (2) physiotherapy in the management of LSF is mainly characterised by one-size-fits-all care, rather than care based on evaluating the specific functional needs of the patients [15, 16]; and (3) there is no uniformity or low uniformity in the different aspects of the content of the physiotherapy management (e.g. the necessity of preoperative care, multidisciplinary treatment and the contents of advice); the current physiotherapy practice needs to be reconsidered.

A shift from postoperative care to preoperative care in patients undergoing major surgery and at-risk for poor outcomes could decrease costs, improve functional outcomes, and in some cases, prevent complications and death [17]. This may hold true for individuals undergoing LSF surgery as well [18, 19]. Preoperatively predicting which patients will not benefit from LSF has proven to be quite challenging, as most medical and surgical factors have very little predictive value [20, 21]. Our data demonstrates that pre- or postoperative risk-stratification and/or optimisation are not utilised in daily clinical practice. Nonetheless, evidence tells us that functional measures are vital for risk assessment and provision of optimal care before and after major surgery [22–24].

An interesting finding was that there is little agreement on the “dos and don’ts” after LSF surgery. Even though nearly all physiotherapists report that they provide information and recommendations, we found there is not only little uniformity in the content of recommendations but also in when to resume the activities of daily life. Topics that are almost never discussed are: (when to) return to sports and (when to) return to work, despite these being absolutely crucial for reintegration and participation in society. This apparent dissensus among health professionals on the timing of postoperative activities might be caused or at least maintained by the scarce, and somewhat counter-intuitive, literature on this topic [25, 26].

Conclusion

Literature on the current rehabilitation policy of physiotherapy treatment before and after LSF is scarce. Nonetheless, many patients who undergo LSF are treated by a physiotherapist. Expert physiotherapy practice before and after LSF in the Netherlands is mainly aimed at getting patients back onto their feet by teaching and training transfers, walking and stair climbing. However, in terms of diagnostic procedures, the type of recommendations given to the patient, outcome evaluation/monitoring and discharge logistics we found considerable differences between therapists’ responses. Considering the latter, we think that best evidence/practice guidelines are needed to help guide physiotherapists in the management of people undergoing LSF.

References

Nederlandse Vereniging van Neurochirurgen.(2009) Spondylodese (vastzetten van de rug). NVvN, Leiden, the Netherlands

Rajaee SS, Bae HW, Kanim LE, Delamarter RB (2012) Spinal fusion in the United States: analysis of trends from 1998 to 2008. Spine 37:67–76. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820cccfb

Rushton A, Eveleigh G, Petherick E-J, Heneghan N, Bennett R, James G et al (2012) Physiotherapy rehabilitation following lumbar spinal fusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 2:1–11. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000829

Rushton A, Heneghan N, Heap A, White L, Eveleigh G, Wright C (2014) Survey of current physiotherapy practice for patients undergoing lumbar spinal fusion in the UK. Spine 39:E1380–E1387. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000573

Staal JB, Hendriks EJM, Heijmans M, Kiers H, Rutten AML-BG, van Tulder MW et al (2013) KNGF-richtlijn Lage rugpijn. KNGF 7:1–13

Stichting Dutch Hospital Data. Kengetallen Nederlandse Ziekenhuizen (2012) Dutch Hospital Data, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP (2008) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61:344–349. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

Eysenbach G (2004) Improving the quality of Web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 6:e34. doi:10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34

Kirschneck M, Kirchberger I, Amann E, Cieza A (2011) Validation of the comprehensive ICF core set for low back pain: the perspective of physiotherapists. Manual Therapy 16:364–372. doi:10.1016/j.math.2010.12.011

Qualtrics (2013) Qualtrics: Online Survey Software & Insight Platform. Provo, Utah, USA

Milidonis MK, Godges JJ, Jensen GM (1999) Nature of clinical practice for specialists in orthopaedic physiotherapy. J Orthop Sports Physiother 29:240–247. doi:10.2519/jospt.1999.29.4.240

Oosting E, Hoogeboom TJ, Elings J, Van Der Sluis G, Van Meeteren NL (2009) Inhoud en methodologische kwaliteit van ziekenhuisprotocollen fysiotherapie na totale knieartroplastiek. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Fysiotherapie. 119:186

Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E (2011) Hospitalization-associated disability “she was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure”. JAMA 306:1782–1793. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1556

Chen CY, Chang CW, Lee ST, Chen YC, Tang SF, Cheng CH, Lin YH (2015) Is rehabilitation intervention during hospitalization enough for functional improvements in patients undergoing lumbar decompression surgery? A prospective randomized controlled study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 129(Suppl 1):S41–S46

Shepard KF, Hack LM, Gwyer J, Jensen GM (1999) Describing expert practice in physiotherapy. Qual Health Res 9:746–758. doi:10.1177/104973299129122252

Lopopolo RB (1999) Hospital restructuring and the changing nature of the physiotherapist’s role. Physiotherapy 79:171–185

Hoogeboom TJ, Dronkers JJ, Hulzebos EHJ, van Meeteren NLU (2014) Merits of exercise therapy before and after major surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 27:161–166. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000000062

Nielsen PR, Jørgensen LD, Dahl B, Pedersen T, Tønnesen H (2010) Prehabilitation and early rehabilitation after spinal surgery: randomized clinical trial. Clin Rehabil 24:137–148. doi:10.1177/0269215509347432

Nielsen PR, Andreasen J, Asmussen M, Tønnesen H (2008) Costs and quality of life for prehabilitation and early rehabilitation after surgery of the lumbar spine. BMC Health Services Res 8:209. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-8-209

Willems P, Staal J, Walenkamp G, de Bie R (2013) Spinal fusion for chronic low back pain: systematic review on the accuracy of tests for patient selection. Spine J 13:99–109. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2012.10.001

Willems P, de Bie R, Oner C, Castelein R, de Kleuver M (2011) Clinical decision making in spinal fusion for chronic low back pain Results of a nationwide survey among spine surgeons. BMJ Open 1:e000391. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000391

Malani P (2009) Functional status assessment in the preoperative evaluation of older adults. JAMA 302:1582–1583. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1453

Hingorani AD, van der Windt DA, Riley RD, Abrams K, Moons KGM, Steyerberg EW, Schroter S, Sauerbrei W, Altman DG, Hemingway H (2013) Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 4: stratified medicine research. BMJ 5793:1–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.e5793

Oestergaard LG, Maribo T, Bünger CE, Christensen FB (2012) The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure’s semi-structured interview: its applicability to lumbar spinal fusion patients. A prospective randomized clinical study. Eur Spine J 21:115–121. doi:10.1007/s00586-011-1957-5

Oestergaard LG, Nielsen CV, Bünger CE, Svidt K, Christensen FB (2013) The effect of timing of rehabilitation on physical performance after lumbar spinal fusion: a randomized clinical study. Eur Spine J 22:1884–1890. doi:10.1007/s00586-013-2717-5

Oestergaard LG, Nielsen CV, Bünger CE, Sogaard R, Fruensgaard S, Helmig P, Christensen FB (2012) The effect of early initiation of rehabilitation after lumbar spinal fusion: a randomized clinical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 37:1803–1809

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all at Zuyd University of Applied Sciences (in particular Dr. Ronnie Minnaard), Maastricht University Medical Centre+, the Dutch Association for Physiotherapy in Hospitals (NVZF) (in particular Helen Andersson), and the Association of Physiotherapy Managers (VLF) who were involved in this study. Finally, we want to thank all of the respondents who were willing to participate in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or financial involvement in any organisation or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. Due to the nature of this study, assessment by a medical ethics review board was not necessary.

Additional information

E. R. C. Janssen and E. E. M. Scheijen contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Janssen, E.R.C., Scheijen, E.E.M., van Meeteren, N.L.U. et al. Determining clinical practice of expert physiotherapy for patients undergoing lumbar spinal fusion: a cross-sectional survey study. Eur Spine J 25, 1533–1541 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4433-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4433-4