Abstract

The use of low-dose aspirin (LDA) is well known to be associated with an increased risk of serious upper gastrointestinal complications, such as peptic ulceration and bleeding. Until recently, attention was mainly focused on aspirin-induced damage of the stomach and duodenum. However, recently, there has been growing interest among gastroenterologists on the adverse effects of aspirin on the small bowel, especially as new endoscopic techniques, such as capsule endoscopy (CE) and balloon-assisted endoscopy, have become available for the evaluation of small bowel lesions. Preliminary CE studies conducted in healthy subjects have shown that short-term administration of LDA can induce mild mucosal inflammation of the small bowel. Furthermore, chronic use of LDA results in a variety of lesions in the small bowel, including multiple petechiae, loss of villi, erosions, and round, irregular, or punched-out ulcers. Some patients develop circumferential ulcers with stricture. In addition, to reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal lesions in LDA users, it is important for clinicians to confirm the differences in the gastrointestinal toxicity between different types of aspirin formulations in clinical use. Some studies suggest that enteric-coated aspirin may be more injurious to the small bowel mucosa than buffered aspirin. The ideal treatment for small bowel injury in patients taking LDA would be withdrawal of aspirin, however, LDA is used as an antiplatelet agent in the majority of patients, and its withdrawal could increase the risk of cardiovascular/cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality. Thus, novel means for the treatment of aspirin-induced enteropathy are urgently needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low-dose aspirin (LDA) is among the most commonly prescribed drugs worldwide. Low-dose aspirin is widely used in clinical practice for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and thrombotic cerebrovascular events [1–3]. However, use of LDA has also come to be well-recognized to be associated with the risk of serious upper gastrointestinal complications, such as peptic ulceration and bleeding [4, 5]. With the aging of our society, the use of LDA has continued to increase, and the propensity of aspirin, even at low doses, to cause gastrointestinal injury has become a clinical problem that needs attention.

Until recently, most studies on aspirin-induced damage focused on lesions in the stomach and duodenum, and the potential of LDA to cause injury to the small bowel remained under debate. One of the reasons was the difficulty in assessing the small bowel, and aspirin-induced enteropathy still remained to be characterized in detail. Recent advances in diagnostic endoscopy such as capsule endoscopy (CE) and double-balloon endoscopy [6, 7] enable direct visualization of the small bowel and have shed some light on the small bowel injury induced by aspirin and other conventional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [8–14]. Some case reports and clinical studies have revealed that chronic use of LDA has the potential to cause a variety of severe lesions in the small bowel, including erosions, ulcerations, and circumferential strictures [14–18]. In turn, these lesions can be associated with complications such as acute bleeding, obstruction, and occult gastrointestinal bleeding [14, 16]. The aim of this review is to discuss the current status of small bowel injury in LDA users.

Is LDA really harmful to the small bowel in humans?

The pathogenesis of NSAID/aspirin-enteropathy is multifactorial and complex than formerly thought, but still remains to be clearly understood [19]. In patients taking NSAIDs, the small bowel mucosa is exposed multiple times to the drugs: initially, the topical exposure before and during absorption of the drug, then, exposure during systemic distribution of the drug, and finally, for the case of some drugs, but not aspirin, repetitive topical exposure during its enterohepatic circulation. Such repetitive exposure plays an important role in the pathogenesis of NSAID/aspirin-induced enteropathy [20, 21]. NSAIDs have a direct toxic effect on enterocytes, as described by the so-called “three hit hypothesis” [22]. First, NSAIDs solubilize the lipid component of phospholipids on the mucosal surface, causing direct damage to the epithelial cell mitochondria [23]. Second, the mitochondrial damage depletes intercellular energy, leading to calcium efflux and formation of free radicals, and in turn, disruption of the intercellular junctions occurs, with an increase in the mucosal permeability in the small bowel mucosa. Third, the mucosal barrier becomes weakened and overcome by the intraluminal contents (such as bile acids, luminal bacteria and their degradation products, food macromolecules, and other toxins), resulting in inflammation [21]. The second important pathogenetic mechanism of NSAID-induced enteropathy is the systemic effect associated with prostaglandin depletion. While the pathogenesis of enteropathy was initially thought to be associated with cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 inhibition only, it has been demonstrated in experiments carried out in mice that COX-1 deficiency or inhibition and COX-2 inhibition are not detrimental to the small bowel integrity [24]. Dual inhibition of the COX enzymes, in the absence of the topical effect, leads to the characteristic small bowel damage seen with indomethacin administration. In regard to aspirin, experimental studies have shown that aspirin does not induce gastric mucosal injury despite inhibiting prostaglandin biosynthesis [25].

Although aspirin use, including LDA use, has been shown to increase the risk of gastroduodenal ulcers, it is generally believed that aspirin is safe for the small bowel beyond the duodenum. The topical effect of aspirin was estimated to be mainly limited to the gastroduodenum due to the rapid absorption of aspirin in the stomach and the duodenum, and the lack of enterohepatic recirculation [26]. Experimental studies have shown that aspirin does not induce damage of the small bowel. For the case of human beings, a number of noninvasive tests have been developed to evaluate the indirect parameters of mucosal damage such as measurement of the intestinal permeability or surrogate markers of inflammation in stools. Studies investigating intestinal damage have been performed in a limited number of aspirin users and shown little evidence of increased intestinal permeability [27–30]. Increased intestinal mucosal permeability has been observed in patients taking high-dose aspirin [27, 31], however, data showing that “low-dose” aspirin induces intestinal damage are scarce and controversial. Leung et al. [15] reported a case of severe enteropathy induced by LDA, which changed our perception based on intestinal permeability and fecal inflammatory marker studies that aspirin does not cause small bowel damage.

In a pilot CE study, we examined the incidence of small bowel injury in healthy volunteers administered with low-dose enteric-coated aspirin for 14 days [13]. Healthy subjects (n = 10) were randomly assigned, by a cross-over method including a washout period of at least 4 weeks, to receive LDA (enteric-coated aspirin 100 mg/day) for 14 days (aspirin group) or no drug for 14 days (control group). All subjects underwent CE at the end of each administration period. Small bowel lesions were found at a significantly higher incidence following administration of aspirin for 2 weeks as compared to that in the group not given any drug (80 vs. 20 %; p = 0.023); however, there was no significant difference in the incidence of small bowel mucosal breaks (30 vs. 0 %; p = 0.210). The main conclusion from this crossover, but small-scale, study was that short-term administration of LDA was associated with only ‘mild’ mucosal inflammation of the small bowel. On the other hand, Smecol et al. [32] carried out a multidimensional assessment (permeability test, fecal calprotectin, and CE) to evaluate whether short-term administration of LDA can cause injury to the small bowel mucosa. They reported increased fecal calprotectin levels after administration of 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin for 14 days in 20 healthy volunteers. Ten of the 20 healthy subjects exhibited increased intestinal permeability over the cut-off value (lactulose/mannitol ratio >0.025) after aspirin intake. CE revealed ten patients (50 %) with mucosal damage that had not been apparent in the baseline CE (six patients had petechiae, three had erosions, and one had bleeding stigmata in two ulcers). In a preliminary study conducted by Shiotani et al. [33], 12 of 20 healthy volunteers (60 %) showed large erosions or ulcers after administration of 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin for only 1 week. Murakami et al. [34] also performed CE in 11 healthy male subjects who had been administered 100 mg of aspirin for 4 weeks. In their study, each subject underwent CE after 1 week and 4 weeks of treatment with LDA. The study showed that the number of subjects with mucosal breaks in the jejunum (defined as multiple erosions and/or ulcers) was 1 at 1 week and 1 at 4 weeks, and that with mucosal breaks in the ileum was 6 at 1 week and 7 at 4 weeks. Data from these pilot studies suggest that short-term use of LDA is associated with an increased incidence of small bowel mucosal injury. The clinical significance of the small bowel injury detected by CE following short-term administration of LDA is not yet clear. While in clinical practice, LDA treatment is usually indicated for a long-term, the results of these short-term studies do not automatically indicate the potential long-term mucosal effects of LDA treatment. The most recent studies carried out to evaluate the small bowel injuries induced by chronic LDA use are outlined below.

Characteristics of small bowel injury seen in chronic LDA users

Chronic blood-loss anemia and occult bleeding is not a rare complication of LDA, although gastroduodenal or colonic mucosal injury is often absent in such cases [16, 35]. Some patients on LDA develop serious bleeding with no identifiable source, iron deficiency anemia, or even abdominal symptoms. These data suggest that LDA can cause small bowel mucosal injury.

The characteristics of small bowel injury seen in chronic LDA users have been reported recently [14, 36–41]. Representative endoscopic findings in patients taking LDA are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The reported prevalence of small bowel injury in long-term LDA users is 88.5–100 % [14, 36, 41]. We found that among 22 chronic LDA users, the most common lesions in the small bowel were erosions (14 patients 63.6 %) and ulcers (ten patients 45.5 %) [14]. In this study, the enteropathy included multiple petechiae/red spots, loss of villi, scars, mucosal erosions, and round, irregular or punched-out ulcers. Two patients had circumferential ulcers with stricture formation. In their study, Watanabe et al. [36] reported mucosal breaks (erosions/ulcers) in ten of 11 patients, but found no case of strictures. In the study reported by Shiotani et al. [37], among 22 chronic LDA uses, small erosions were detected in 15 (68.2 %) cases and large erosions in seven (31.8 %). The high prevalence of small bowel injury in these reports could be related to the selection criteria of the subjects. In two reports, only symptomatic patients who had developed gastrointestinal bleeding and abdominal pain were investigated. In the other study, patients were restricted to individuals who had developed gastric ulcers, and predisposing factors in the patient’s background including genetic differences might increase the susceptibility of the small bowel to aspirin-induced injury. Among 1,035 patients registered in the Japanese Study Group for Double-Balloon Endoscopy (JSG-DBE) database, Matsumoto et al. [17] demonstrated that aspirin was less harmful to the small bowel mucosa than other NSAIDs; they identified mucosal breaks in only six out of 20 patients (30 %) who were taking aspirin. Aspirin-induced gastrointestinal toxicity is seemingly dose-dependent [42], and LDA may be less harmful to the small bowel mucosa than full-dose aspirin or other NSAIDs. Further studies are needed to investigate the prevalence of small bowel injury in chronic LDA users.

Previous reports discussing the characteristics of small bowel injury in chronic LDA users mostly suggested that ulcers are observed mainly in the distal part of the small bowel [14, 38–40]. We showed using the Lewis scoring system, which can quantify small bowel mucosal changes associated with any inflammatory process [43], that the mucosal injuries in chronic LDA users tended to be of greater severity in the distal part of the small bowel [40]. However, other studies have failed to identify any such trend in the anatomic distribution of the small bowel mucosal breaks in LDA users [41, 44]. A possible reason for this discrepancy among studies is that in relation to the CE findings, some of these studies did not differentiate mucosal breaks from other terms, such as erosions or ulcers, in order to simplify the evaluation of aspirin-induced small bowel mucosal injury. Another possible reason is the interindividual differences among the patients enrolled in the studies. Some studies [41, 44] included asymptomatic patients with unexplained iron deficiency anemia, while others [14, 39, 40] included symptomatic patients, with symptoms such as gastrointestinal bleeding and abdominal pain. These results may also be influenced by the difference in the intestinal microbial flora between the proximal and distal small bowel [45]. The luminal bacterial load increases from the proximal to the distal small bowel and these changes may play a role in the pathogenesis of NSAID/aspirin-induced injury [46, 47]. However, the actual influence of enterobacteria on aspirin-induced small bowel injury remains poorly understood and further investigations are needed.

As stated above, CE has revealed numerous inflammatory lesions and has shed some more light on the small bowel injury induced by aspirin. Despite these investigations, the precise clinical significance of aspirin-associated injury remains unclear. Almost all the patients taking LDA show some degree of bowel injury, however, it has not been investigated as to whether these lesions of the small bowel can actually explain the iron deficiency anemia of unknown cause in patients on LDA. In one study, we demonstrated that in patients with small bowel mucosal injury, the hemoglobin concentration improved significantly in parallel with the small bowel mucosal lesions in patients treated with probiotics [41], suggesting that these mucosal injuries might induce microbleeding and actually be the cause of the anemia of unknown cause. Further studies are needed to elucidate the correlation between the severity of the small bowel injury and changes in the blood hemoglobin concentration in chronic LDA users.

Difference in the incidence of small bowel injury between patients receiving buffered aspirin and those receiving enteric-coated aspirin

In order to reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal injury in LDA users, it is important for clinicians to confirm the differences in the gastrointestinal toxicity between different types of aspirin formulations in clinical use. To potentially avoid gastric mucosal injury caused by the topical irritant effect of aspirin, two types of formulations (buffered aspirin and enteric-coated aspirin) have been developed and are widely used. Buffered products contain agents such as calcium carbonate, magnesium oxide, and magnesium carbonate, which lower the hydrogen ion concentration of the aspirin particles. The low hydrogen ion concentration increases the gastric solubility of aspirin, thereby decreasing the contact time between aspirin and the gastric mucosa [48]. On the other hand, it has been postulated that enteric-coated formulations of aspirin, which are designed to cancel disintegration in an acid environment and pass through the stomach without undergoing dissolution, may also reduce the risk of gastric injury. Several studies have reported that enteric-coated aspirin causes less severe gastroduodenal injury than uncoated aspirin [49–52]; however, the precise difference in the severity of the small bowel toxicity between these two types of formulations remains unknown.

Enteric-coated formulations show dissolution in the small bowel, with the small bowel rather than the stomach or duodenum being exposed to their potential toxicity. In all of the above-mentioned investigations carried out in volunteers administered LDA, enteric-coated aspirin was the formulation used. Small bowel injuries in these studies have been assumed to be caused by the topical irritant effect of aspirin. In view of this mechanism, it could be explained why enteric-coated aspirin is more toxic for the small bowel mucosa than other types of aspirin. Our study, which included 16 enteric-coated aspirin users and six non-coated aspirin users, demonstrated a higher frequency of small bowel ulcers in patients taking enteric-coated aspirin than in those taking non-coated aspirin (56.3 vs. 16.7 %) [14]. In a subsequent study, we examined the difference in the severity of the small bowel mucosal injury depending on the type of aspirin formulation prescribed in chronic 70 LDA users with suspected small bowel bleeding [53]. Of the 70 patients, 15 were prescribed buffered aspirin, and 55 were prescribed enteric-coated aspirin. The median duration of use of LDA in the patients was 72 months (range, 7–348) in the buffered aspirin group and 60 months (range, 4–411) in the enteric-coated aspirin group. The number of patients with at least one ulcer was significantly higher in the patients taking enteric-coated aspirin than in those taking buffered aspirin (38.2 vs. 6.7 %; p = 0.026). The number of small bowel ulcers was also significantly higher in the patients taking enteric-coated aspirin than in those taking buffered aspirin (p = 0.037). The Lewis scores showed that the aspirin-induced mucosal injury was significantly more severe in the enteric-coated aspirin group than in the buffered aspirin group, especially in the distal part of the small bowel. However, these results should be interpreted with caution. The number of patients taking buffered aspirin (n = 15) in these studies, including in our study, was considerably smaller than the number of patients taking enteric-coated aspirin (n = 55). Moreover, the aspirin doses used were different between people taking buffered aspirin and those taking enteric-coated aspirin. Although aspirin-induced gastrointestinal toxicity is seemingly dose-dependent [42], it remains unclear whether 81 mg of aspirin per day might be less injurious to the small bowel mucosa than 100 mg of aspirin per day. Further studies are required to elucidate these issues.

There has been growing interest among clinicians to clarify the differences in the risk of LDA-associated small bowel bleeding between different types of aspirin formulations. Although it is important to know whether the type of aspirin formulation might affects the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, especially from the small bowel, there have been no reports of small bowel bleeding associated with the use of either enteric-coated or buffered aspirin. Hirata et al. [54] reported that the percentage of patients with clinically significant anemia suspected to have small bowel blood loss tended to be higher among users of enteric-coated aspirin (2 %) than among users of buffered aspirin (0.3 %). Furthermore, they showed that use of enteric-coated aspirin may be associated with an increased incidence of anemia suspected to be caused by blood loss from the small bowel. In their study, presumed small bowel bleeding was a diagnosis made by exclusion rather than by direct confirmation of the source of blood loss. Further studies using small bowel endoscopic techniques, such as CE and balloon-assisted endoscopy, would be desirable to elucidate the influence of the type of aspirin on the risk of small bowel bleeding in chronic LDA users.

Risk factors for small bowel mucosal breaks in chronic LDA users

For the prevention of small bowel injury in patients receiving LDA, it is important to identify the risk factors for the development of such injury in these patients. In regard to the upper gastrointestinal complications associated with aspirin use, it is well recognized that not all patients receiving LDA are at an equivalent risk of developing these complications, and several factors such as advanced age, history of peptic or bleeding ulcer, concomitant use of NSAIDs/other antiplatelet agents/anticoagulants, presence/absence of severe co-morbidities, and high-dose aspirin use, have been reported to influence the risk [55]. Some key strategies have been proposed to minimize the upper-gastrointestinal adverse effects of LDA, such as reducing the influence of modifiable risk factors, reducing the aspirin dose, and concomitant use of a gastroprotective agent, preferably a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). However, there are few data on the risk factors for the development of small bowel injury among patients receiving LDA.

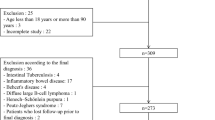

Recently, we conducted the prospective CE study to evaluate the risk factors for the development of small bowel mucosal breaks (ulcers and/or erosions) in 198 chronic LDA users [56]. Of the 198 patients, 24 were taking buffered aspirin, and the remaining 174 were taking enteric-coated aspirin. In regard to concomitant use of acid suppressants, 72 patients were taking PPIs [omeprazole (n = 29), lansoprazole (n = 27), or rabeprazole (n = 16)] and 35 were taking histamine-2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) [famotidine (n = 22), lafutidine (n = 10), or nizatidine (n = 3)] for more than 1 month for primary or secondary prevention of gastric or duodenal ulcers. The daily doses of the PPIs were as follows: omeprazole 20 mg (n = 23), 10 mg (n = 6); lansoprazole 30 mg (n = 4), 15 mg (n = 23); rabeprazole 20 mg (n = 1), 10 mg (n = 15). The analysis identified PPI use (odds ratio 2.04, 95 % confidence interval 1.05–3.97) and use of enteric-coated aspirin (odds ratio 4.05, 95 % confidence interval 1.49–11.0) as independent risk factors for the presence of mucosal breaks in LDA users. The small bowel injuries in the patients taking PPIs did not show a dose–response relationship. In the analysis using the Lewis scoring index, use of PPI and use of enteric-coated aspirin were identified as significant risk factors for the development of “mild” mucosal changes, with odds ratios of 5.81 and 3.28, respectively. The analysis revealed that concomitant PPI use was associated with a higher risk of small bowel mucosal breaks in LDA users. In regard to conventional NSAIDs, a recent cross-sectional CE study carried out in over 100 rheumatoid arthritis patients who chronically used NSAIDs users showed that old age, use of PPIs and use of H2RAs were associated with an increased risk of severe NSAID-induced small bowel damage, with odds ratios of 4.16, 5.22, and 3.95, respectively [57]. Although PPIs have been demonstrated to reduce the incidence of gastroduodenal injury associated with the use of NSAIDs or aspirin [58], their protective effect against small bowel injuries remains controversial.

The pathogenesis of NSAID/aspirin-induced enteropathy is likely to be multifactorial. Recent experimental studies have demonstrated that enterobacteria play a crucial role in the development of NSAID-induced small bowel injury [59–61]. Gastric acid can suppress most bacteria, and chronic acid suppression by PPIs could lead to small bowel bacterial overgrowth [62–64]. Therefore, acid suppression by intake of PPIs could exacerbate the small bowel injury induced by NSAIDs or aspirin. Some recent studies have suggested the possibility that acid suppression may exacerbate NSAID/aspirin-induced small bowel injury. Wallace et al. [65] demonstrated that PPIs exacerbated NSAID-induced small bowel injury by inducing dysbiosis. Moreover, we demonstrated in a randomized controlled CE study that co-administration of probiotics alleviated the severity of the small bowel lesions in both LDA and PPI users [41]. However, because experimental studies have reported contradictory results on the relationship between small bowel injury and use of PPIs [66, 67], further studies are required to confirm this notion. This interesting finding is in conflict with the known decrease in the risk of aspirin-induced gastric ulcers and ulcer complications associated with PPI use. It is necessary for clinicians to recognize this dilemma of PPI therapy, and novel means for treatment of aspirin-induced gastroenteropathy are urgently needed.

Prevention and treatment of small bowel injury induced by LDA

The ideal treatment for small bowel injury in patients taking LDA would be withdrawal of aspirin, however, LDA is used as an antiplatelet agent in the majority of patients, and its withdrawal could increase the risk of cardiovascular/cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality. Thus, novel means for the treatment of small bowel injury associated with LDA use are urgently needed.

To date, several investigations have been carried out to identify means to prevent or treat aspirin-induced small bowel injury (Table 1). In their study carried out in 11 patients who had been on low-dose enteric-coated aspirin for more than 3 months for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and were found to have gastric ulcers, Watanabe et al. [36] reported the efficacy of misoprostol against the aspirin-induced enteropathy. Misoprostol significantly decreased the number of red spots and the number of mucosal breaks (erosions/ulcers), with complete disappearance of the multiple mucosal breaks in four of seven patients. However, misoprostol is often poorly tolerated because of its side effects, such as diarrhea and abdominal pain. Indeed, in this pilot study, three of the 11 patients who received misoprostol discontinued the drug owing to the development of severe watery diarrhea.

Recently, we conducted a randomized controlled trial in which we performed CE to examine the efficacy of probiotic treatment on small bowel mucosal injury in chronic LDA users [41]. Probiotics are living microorganisms that are components of the natural flora, and are important for the health and well-being of the host [68]. Probiotic bacteria have been demonstrated to have possible therapeutic effects against intestinal inflammation [69, 70]. Patients taking low-dose enteric-coated aspirin at the dose of 100 mg once daily (for more than 3 months) plus omeprazole at 20 mg once daily, who were found to have unexplained iron deficiency anemia (decline in the blood hemoglobin concentration to below 13 g/dl in men and 12 g/dl in women with iron deficiency) were eligible for inclusion in the study and for the baseline CE. Thirty-five patients participated in this trial and underwent a baseline CE examination at study entry. Among the 35 patients, 29 were found to be eligible for inclusion in this analysis; of these, 15 were randomly assigned to the Lactobacillus casei (L. casei) group and 14 to the control group. Patients in the L. casei group received viable L. casei at doses of 45 × 108–63 × 109 colony-forming units (CFU) daily for 3 months, while patients in the control group received no probiotics. After the randomization, four patients, including two from the L. casei group and two from the control group, were excluded from our final analysis. Thus, post-treatment CE for analysis of the changes in the small bowel lesions was carried out in 13 patients of the L. casei group and 12 patients of the control group. In the L. casei group, the number of mucosal breaks had decreased significantly from a median of 3 at the baseline CE to a median of 1 in the post-treatment CE (p = 0.008). In the control group, no significant difference in the median number of mucosal breaks was observed between the baseline and post-treatment CE. A decrease in the percentage of patients with at least one mucosal break was observed in response to probiotic treatment in the L. casei group (84.6 % (11/13) in the baseline CE vs. 53.8 % (7/13) in the post-treatment CE), however, the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.202). On the other hand, in the control group, the percentage of patients with mucosal breaks increased slightly during the study period; there was no significant difference within the group between these time-points (p > 0.999). In this analysis, the change in the number of mucosal breaks from the baseline CE to the post-treatment CE was significantly greater in the L. casei group (−5.3 ± 10.2) than that in the control group (0.8 ± 7.9) (p = 0.039). No side effects or significant changes from the baseline values of any of the laboratory parameters examined were recorded in either group of patients. Recent studies have supported the potential therapeutic role of probiotics in small bowel inflammation induced by NSAIDs or aspirin. Watanabe et al. [60] reported that the L. casei strain Shirota protected against indomethacin-induced small bowel injury in rats, and that its probiotic effects may be mediated by the anti-inflammatory effects of lactic acid. More recently, Montalto et al. [71] showed that treatment with a probiotic mixture (VSL#3) containing L. casei significantly reduced the fecal calprotectin concentrations in healthy volunteers receiving indomethacin. From these data, it would appear that probiotics have the potential to prevent aspirin-induced small bowel injury.

Rebamipide has been used across Asia for the treatment of gastric ulcers and gastric lesions such as erosions and edema associated with acute gastritis [72–74]. It has been well documented that rebamipide increases the endogenous prostaglandin levels, scavenges free radicals, and suppresses inflammation in the gastric mucosa [75–77]. Through these actions, rebamipide has been also shown to be useful in prevention aspirin-induced gastrointestinal injuries. Mizukami et al. [34] reported that rebamipide had a preventive effect against aspirin-induced small bowel mucosal breaks in the ileum as compared to placebo. Moreover, in a randomized controlled trial carried out in patients on LDA and/or an NSAID for more than 3 months, rebamipide was shown to be effective in healing the small bowel erosions and ulcers [78]. From these data, it is reasonable to speculate that to some extent, rebamipide might serve to reduce the incidence/severity of small bowel injury in patients receiving LDA.

References

Awtry EH, Loscalzo J. Aspirin. Circulation. 2000;101:1206–18.

Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high-risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71–86.

Patrono C, García Rodríguez LA, Landolfi R, Baigent C. Low-dose aspirin for the prevention of atherothrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2373–83.

Weil J, Colin-Jones D, Langman M, Lawson D, Logan R, Murphy M, et al. Prophylactic aspirin and risk of peptic ulcer bleeding. BMJ. 1995;310:827–30.

Patrono C. Aspirin as an antiplatelet drug. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1287–94.

Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405:417.

Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashiwaza T, Miyata T, Iino S, et al. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:216–20.

Graham DY, Opekun AR, Willingham FF, Qureshi WA. Visible small-intestinal mucosal injury in chronic NSAID users. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:55–9.

Maiden L, Thjodleifsson B, Theodors A, Gonzalez J, Bjarnason I. A quantitative analysis of NSAID-induced small bowel pathology by capsule endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1172–8.

Maiden L, Thjodleifsson B, Seigal A, Bjarnason II, Scott D, Birgisson S, et al. Long-term effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygenase-2 selective agents on the small bowel: a cross-sectional capsule enteroscopy study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1040–5.

Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Zlotnick S, Fort JG, Investigators. Video capsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omeprazole, and placebo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:133–41.

Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Aisenberg J, Bhadra P, et al. Small bowel mucosal injury is reduced in healthy subjects treated with celecoxib compared with ibuprofen plus omeprazole, as assessed by video capsule endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1211–22.

Endo H, Hosono K, Inamori M, Kato S, Nozaki Y, Yoneda K, et al. Incidence of small bowel injury induced by low-dose aspirin: a crossover study using capsule endoscopy in healthy volunteers. Digestion. 2009;79:44–51.

Endo H, Hosono K, Inamori M, Nozaki Y, Yoneda K, Fujita K, et al. Characteristics of small bowel injury in symptomatic chronic low-dose aspirin users: the experience of two medical centers in capsule endoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:544–9.

Leung WK, Bjarnason I, Wong VW, Sung JJ, Chan FK. Small bowel enteropathy associated with chronic low-dose aspirin therapy. Lancet. 2007;369:614.

Manetas M, O’Loughlin C, Kelemen K, Barkin JS. Multiple small-bowel diaphragms: a cause of obscure GI bleeding diagnosed by capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:848–51.

Matsumoto T, Kudo T, Esaki M, Yano T, Yamamoto H, Sakamoto C, et al. Prevalence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced enteropathy determined by double-balloon endoscopy: a Japanese multicenter study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:490–6.

Stattery J, Warlow CP, Shorrock CJ, Langman MJ. Risks of gastrointestinal bleeding during secondary prevention of vascular events with aspirin—analysis of gastrointestinal bleeding during the UK-TIA trial. Gut. 1995;37:509–11.

Higuchi K, Umegaki E, Watanabe T, Yoda Y, Morita E, Murano M, et al. Present status and strategy of NSAIDs-induced small bowel injury. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:879–88.

Davies NM, Saleh JY, Skjodt NM. Detection and prevention of NSAID-induced enteropathy. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2000;3:137–55.

Reuter BK, Davies NM, Wallace JL. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy in rats: role of permeability, bacteria, and enterohepatic circulation. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:109–17.

Bjarnason I, Hayllar J, MacPherson AJ, Russell AS. Side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the small intestine in humans. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1832–47.

Somasundaram S, Sigthorsson G, Simpson RJ, Watts J, Jacob M, Tavares IA, et al. Uncoupling of intestinal mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and inhibition of cyclooxygenase are required for the development of NSAID-enteropathy in the rat. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:639–50.

Sigthorsson G, Simpson RJ, Walley M, Anthony A, Foster R, Hotz-Behoftsitz C, et al. COX-1 and 2, intestinal integrity, and pathogenesis of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1913–23.

Ligumsky M, Golanska EM, Hansen DG, Kauffman GL. Aspirin can inhibit gastric mucosa cyclo-oxygenase without causing lesions in rat. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:756–61.

Somasundaram S, Rafi S, Hayllar J, Sigthorsson G, Jacob M, Price AB, et al. Mitochondrial damage: a possible mechanism of the “topical” phase of NSAID induced injury to the rat intestine. Gut. 1997;41:344–53.

Bjarnason I, Williams P, Smethurst P, Peters TJ, Levi AJ. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and prostaglandins on the permeability of the human small intestine. Gut. 1986;27:1292–7.

Sigthorsson G, Tibble J, Hayllar J, Menzies I, Macpherson A, Moots R, et al. Intestinal permeability and inflammation in patients on NSAIDs. Gut. 1998;43:506–11.

Catanoso M, Lo Gullo R, Giofré MR, Pallio S, Tortora A, Lo Presti M, et al. Gastro-intestinal permeability is increased in patients with limited systemic sclerosis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30:77–81.

Jenkins RT, Rooney PJ, Jones DB, Bienenstock J, Goodacre RL. Increased intestinal permeability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a side-effect of oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy? Br J Rheumatol. 1987;26:103–7.

Twiss IM, Burggraaf J, Schoemaker RC, van Elburg RM, den Hartigh J, Cohen AF, et al. The sugar absorption test in the evaluation of the gastrointestinal intolerance to bisphosphonates: studies with oral pamidronate. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:431–7.

Smecuol E, Pinto Sanchez MI, Suarez A, Argonz JE, Sugai E, et al. Low-dose aspirin affects the small bowel mucosa: results of a pilot study with a multidimensional assessment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:524–9.

Shiotani A, Haruma K, Nishi R, Fujita M, Kamada T, Honda K, et al. Randomized, double-blind, pilot study of geranylgeranylacetone versus placebo in patients taking low-dose enteric-coated aspirin. Low-dose aspirin-induced small bowel damage. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:292–8.

Mizukami K, Murakami K, Abe T, Inoue K, Uchida M, Okimoto T, et al. Aspirin-induced small bowel injuries and the preventive effect of rebamipide. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:5117–22.

Mehdizadeh S, Lo SK. Treatment of small-bowel diaphragm disease by using double-balloon enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:1014–7.

Watanabe T, Sugimori S, Kameda N, Machida H, Okazaki H, Tanigawa T, et al. Small bowel injury by low-dose enteric-coated aspirin and treatment with misoprostol: a pilot study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1279–82.

Shiotani A, Honda K, Murao T, Ishii M, Fujita M, Matsumoto H, et al. Combination of low-dose aspirin and thienopyridine exacerbates small bowel injury. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:281–6.

Watari I, Oka S, Tanaka S, Aoyama T, Imagawa H, Shishido T, et al. Effectiveness of polaprezinc for low-dose aspirin-induced small-bowel mucosal injuries as evaluated by capsule endoscopy: a pilot randomized controlled study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:108.

Watari I, Oka S, Tanaka S, Igawa A, Nakano M, Aoyama T, et al. Comparison of small-bowel mucosal injury between low-dose aspirin and non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a capsule endoscopy study. Digestion. 2014;89:225–31.

Endo H, Hosono K, Higurashi T, Sakai E, Iida H, Sakamoto Y, et al. Quantitative analysis of low-dose aspirin-associated small bowel injury using a capsule endoscopy scoring index. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:56–61.

Endo H, Higurashi T, Hosono K, Sakai E, Sekino Y, Iida H, et al. Efficacy of Lactobacillus casei treatment on small bowel injury in chronic low-dose aspirin users: a pilot randomized controlled study. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:894–905.

Cryer B, Feldman M. Effects of very low dose daily, long-term aspirin therapy on gastric, duodenal, and rectal prostaglandin levels and on mucosal injury in healthy humans. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:17–25.

Gralnek IM, Defranchis R, Seidman E, Leighton JA, Legnani P, Lewis BS. Development of a capsule endoscopy scoring index for small bowel mucosal inflammatory change. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:146–54.

Ehrhard F, Nazeyrollas P, Brixi H, Heurgue-Berlot A, Thiéfin G. Proximal predominance of small bowel injury associated with uncoated low-dose aspirin therapy: a video capsule study in chronic users. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:1265–72.

Fujimori S, Gudis K, Takahashi Y, Seo T, Yamada Y, Ehara A, et al. Distribution of small intestinal mucosal injuries as a result of NSAID administration. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40:504–10.

Watanabe T, Higuchi K, Kubota A, Nishio H, Tanigawa T, Shiba M, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small intestinal damage is Toll-like receptor 4 dependent. Gut. 2008;57:181–7.

Konaka A, Kato S, Tanaka A, Kunikata T, Korolkiewicz R, Takeuchi K. Roles of enterobacteria, nitric oxide and neutrophil in pathogenesis of indomethacin-induced small intestinal lesions in rats. Pharmacol Res. 1999;40:517–24.

Banoob DW, McCloskey WW, Webster W. Risk of gastric injury with enteric- versus nonenteric-coated aspirin. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:163–6.

Dammann HG, Burkhardt F, Wolf N. Enteric coating of aspirin significantly decreases gastroduodenal mucosal lesions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1109–14.

Blondon H, Barbier JP, Mahé I, Deverly A, Kolsky H, Bergmann JF. Gastroduodenal tolerability of medium dose enteric-coated aspirin: a placebo controlled endoscopic study of a new enteric-coated formation versus regular formation in healthy volunteers. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2000;14:155–7.

Lanza FL, Royer GL Jr, Nelson RS. Endoscopic evaluation of the effects of aspirin, buffered aspirin, and enteric-coated aspirin on gastric and duodenal mucosa. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:136–8.

Petroski D. Endoscopic comparison of three aspirin preparations and placebo. Clin Ther. 1993;15:314–20.

Endo H, Sakai E, Higurashi T, Yamada E, Ohkubo H, Iida H, et al. Differences in the severity of small bowel mucosal injury based on the type of aspirin as evaluated by capsule endoscopy. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:833–8.

Hirata Y, Kataoka H, Shimura T, Mizushima T, Mizoshita T, Tanida S, et al. Incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cardiovascular disease: buffered aspirin versus enteric-coated aspirin. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:803–9.

Lanas A, Scheiman J. Low-dose aspirin and upper gastrointestinal damage: epidemiology, prevention and treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:163–73.

Endo H, Sakai E, Taniguchi L, Kessoku T, Komiya Y, Ezuka A, et al. Risk factors for small-bowel mucosal breaks in chronic low-dose aspirin users: data from a prospective multicenter capsule endoscopy registry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.03.024.

Watanabe T, Tanigawa T, Nadatani Y, Nagami Y, Sugimori S, Okazaki H, et al. Risk factors for severe nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small intestinal damage. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:390–5.

Arora G, Singh G, Triadafilopoulos G. Proton pump inhibitor for gastroduodenal damage related to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or aspirin: twelve important questions for clinical practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:725–35.

Konaka A, Kato S, Tanaka A, Kunikata T, Korolkiewicz R, Takeuchi K. Roles of enterobacteria, nitric oxide and neutrophil in pathogenesis of indomethacin-induced small intestinal lesions in rats. Pharmacol Res. 1999;40:517–24.

Watanabe T, Nishio H, Tanigawa T, Yamagami H, Okazaki H, Watanabe K, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota prevents indomethacin-induced small intestinal injury: involvement of lactic acid. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G506–13.

Watanabe T, Higuchi K, Kobata A, Nishio H, Tanigawa T, Shiba M, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small intestinal damage is Toll-like receptor 4 dependent. Gut. 2008;57:181–7.

Lombardo L, Foti M, Ruggia O, Chiecchio A. Increased incidence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth during proton pump inhibitor therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:504–8.

Compare D, Pica L, Rocco A, De Giorgi F, Cuomo R, Sarnelli G, et al. Effects of long-tern PPI treatment on producing bowel symptoms and SIBO. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41:380–6.

Jacobs C, Coss Adame E, Attaluri A, Valestin J, Rao SS. Dysmotility and proton pump inhibitor use are independent risk factors for small intestinal bacterial and/or fungal overgrowth. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:1103–11.

Wallace JL, Syer S, Denou E, de Palma G, Vong L, McKnight W, et al. Proton pump inhibitors exacerbate NSAID-induced small intestinal injury by inducing dyspiosis. Gastroenterology. 2011;114:1314–22.

Yoda Y, Amagase K, Kato S, Tokioka S, Murano M, Kakimoto K, et al. Prevention by lansoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, of indomethacin-induced small intestinal ulceration in rats through induction of heme oxygenase-1. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;61:287–94.

Higuchi K, Yoda Y, Amagase K, Kato S, Tokioka S, Murano M, et al. Prevention of NSAID-induced small bowel intestinal mucosal injury: prophylactic potential of lansoprazole. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2009;45:125–30.

Fuller R. Probiotics in human medicine. Gut. 1991;32:439–42.

Rembacken BJ, Snelling AM, Hawkey PM, Chalmers DM, Axon AT. Non-pathogenic Escherichia coli versus mesalazine for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354:635–9.

Sood A, Midha V, Makharia GK, Ahuja V, Singal D, Goswami P, et al. The probiotic preparation, VSL#3 induces remission in patients with mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1202–9.

Montalto M, Gallo A, Curigliano V, D’Onofrio F, Santoro L, Covino M, et al. Clinical trial: the effects of a probiotic mixture on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy—a randomized, double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:209–14.

Park SH, Cho CS, Lee OY, Jun JB, Lin SR, Zhou LY, et al. Comparison of prevention of NSAID-induced gastrointestinal complications by rebamipide and misoprostol: a randomized, multicenter, controlled trial—STORM STUDY. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2007;40:148–55.

Terano A, Arakawa T, Sugiyama T, Suzuki H, Joh T, Yoshikawa T, et al. Rebamipide, a gastro-protective and anti-inflammatory drug, promotes gastric ulcer healing following eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori in a Japanese population: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:690–3.

Kim HK, Kim JI, Kim JK, Han JY, Park SH, Choi KY, et al. Preventive effects of rebamipide on NSAID-induced gastric mucosal injury and reduction of gastric mucosal blood flow in healthy volunteers. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1776–82.

Kent TH, Cardelli RM, Stamler FW. Small intestinal ulcers and intestinal flora in rats given indomethacin. Am J Pathol. 1969;54:237–49.

Sakurai K, Sasabe H, Koga T, Konishi T. Mechanism of hydroxyl radical scavenging by rebamipide: identification of mono-hydroxylated rebamipide as a major reaction product. Free Radic Res. 2004;38:487–94.

Chitapanarux T, Praisontarangkul OA, Lertprasertsuke N. An open-labeled study of rebamipide treatment in chronic gastritis patients with dyspeptic symptoms refractory to proton pump inhibitors. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2896–903.

Kurokawa S, Katsuki S, Fujita T, Saitoh Y, Ohta H, Nishikawa K, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial, healing effect of rebamipide in patients with low-dose aspirin and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug induced small bowel injury. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:239–44.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Endo, H., Sakai, E., Kato, T. et al. Small bowel injury in low-dose aspirin users. J Gastroenterol 50, 378–386 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-014-1028-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-014-1028-x