Abstract

Purpose

Prostate cancer (PC) treatment causes sexual dysfunction (SD) and alters fertility, male identity, and intimate relationships with partners. In Japan, little attention has been paid to the importance of providing care for SD associated with PC treatment. This study is aimed at clarifying the care needs of Japanese men regarding SD associated with PC treatment.

Methods

One-to-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with 44 PC patients to identify their care needs. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results

Four core categories emerged from the analysis. (1) “Need for empathy from medical staff regarding fear of SD”: patients had difficulty confiding in others about their sexual problems, and medical staff involvement in their SD issues was lacking. (2) “Need for information that provides an accurate understanding of SD and coping strategies before deciding on treatment”: lack of information about SD in daily life and difficulty understanding information from medical institutions, caused men to regret their treatment. (3) “Need for professional care for individuals and couples affected by SD”: men faced loss of intimacy because of their partners’ unwillingness to understand their SD issues or tolerate non-sexual relationships. (4) “Need for an environment that facilitates interaction among men to resolve SD issues”: men felt lonely and wanted to interact with other patients about their SD concerns.

Conclusion

These findings may help form care strategies tailored to these needs and applicable to other societies with strong traditional gender norms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Prostate cancer (PC) is the most common type of cancer in men worldwide [1]. Most patients are in their 60s or older, but in recent years, the number of patients in their 40s has been increasing. Japanese patients’ 5-year survival rate from PC is better than that from other carcinomas [2, 3]. As PC treatment ensures a long post-treatment life expectancy, managing side effects is crucial.

PC treatment reduces men’s sexual function and alters their fertility, masculine identity, and relationships with their partners, leading to distress [4, 5]. Care for SD associated with PC treatment has been studied in other countries that provide pharmacotherapy, erectile aids, and psychological support [6, 7]. Recently, self-compassion [8] was shown to alleviate gender-role conflict and distress in PC patients [9]; experts have also examined mindfulness interventions [10]. Many couples recognize and address the importance of communication and the appropriate use of erectile aids and medications to maintain sexual intimacy and a positive attitude toward each other. These trends influence the evolution of their identity as a couple [11].

However, few studies have examined this issue in Japan, where care is insufficient [12, 13]. Physicians rarely attend educational workshops on cancer and sexuality for healthcare providers [14]. Moreover, few nurses are experienced in providing care for PC patients [12]. Consequently, PC patients cope with SD by self-medicating or by changing their cognitions. Some use erectile drugs purchased over the Internet or interrupt treatment at one’s discretion, leading to the deterioration of health. Some decide that their partners do not need sex, leading to separation from the partner [5]. Japanese individuals generally do not publicly complain about sexual problems [15, 16]. Further, many patients lived through the postwar reconstruction period and grew up honoring silent masculinity, which expects men to endure their suffering alone rather than seek help [17]. This makes it difficult for healthcare professionals to identify patients’ care needs. This research is aimed at identifying and developing a deep understanding of PC patients’ needs regarding SD, including the types of care for SD associated with PC treatment from patients’ perspectives. Our research question was “What are Japanese men’s care needs regarding SD-related to PC treatment?”

Methods

Study design and participants

SD associated with PC treatment care needs are guided by individuals’ complex and diverse backgrounds. We used a qualitative inductive research design [18] wherein the complex phenomenon was studied in its natural everyday context, to discover new aspects and generate effective and flexible theories regarding diverse and complex issues.

Participant selection criteria included Japanese men with PC who consented to participate. Exclusion criteria were physical or mental inability to be interviewed and being younger than 20 years. Sampling was conducted with consideration given to population diversity, including various treatment options; a wide range of ages; the full range of married, unmarried, partnered, divorced, or widowed men; various social roles; and urban and rural residents. Sampling was terminated when we reached data saturation and could confirm that no new information would be obtained from additional data.

Procedures

We recruited participants from PC patient associations nationwide and from five hospitals/clinics in urban and rural areas. Research cooperation request forms with the researchers’ contact information were placed at each facility. One-on-one participant interviews were conducted in private conference rooms where privacy could be ensured.

Before the interview, the investigator explained the study purpose and procedures and notified individuals that the interviews would be recorded and that anonymous quotations from the interviews would be included in published results. Volunteers who agreed to participate provided written informed consent. The interviews focused on situations that prompted participants to consider their SD care needs (Table 1).

The interviewer was a middle-aged woman researcher who had attended the Sex Counseling Training Course of the Japan Society for Sexology. The interviewer treated sexuality as a normal part of life and did not judge interviewees on the basis of her values; instead, she motivated them to speak freely and as precisely as possible to provide an accurate picture of their experiences. The interviewer summarized or repeated what she heard to confirm her understanding and focused on interviewees’ emotional dynamics. The interviews, transcriptions, and data analyses were conducted in Japanese to obtain comprehensive narratives. The principal researcher managed recruitment, informed consent, interviews, and initial analysis. Participants were identified with numbers instead of names to ensure privacy. Interviews were conducted from February 2019 to November 2020. Recordings and transcripts remain on a password-protected computer for the study, which complies with the Consolidated Standards for Reporting of Qualitative Research (COREQ) [19].

We conducted qualitative content analysis on the interview data [20] and engaged in thorough discussions until we reached a consensus on the themes that emerged. Researchers explained the research methodology to interviewees and described the categories in detail, quoting interviewees when necessary. Several interviewees confirmed the data integrity, and all were satisfied with the relevance of the data.

Results

Participant characteristics

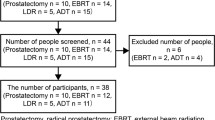

Forty-eight individuals participated; four were excluded on the basis of selection and exclusion criteria. Ten of the remaining 44 participants received radical prostatectomy and 13 received external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT); five received brachytherapy (LDR); 12 had combined androgen blockade (CAB); three received combined treatment; and one was in watchful waiting (Table 2). Ages at diagnosis ranged from 47 to 82, with a median of 66.0. Participants described changes in sexual function related to treatment, such as decreased libido, no or poor erection, no or reduced semen, tender orgasm, changed semen properties, ejaculatory pain, or discomfort.

Care needs of Japanese men for sexual dysfunction associated with PC treatment

The following themes emerged from participants’ care need narratives: “need for empathy from medical staff regarding fear of SD”; “need for information that provides an accurate understanding of SD and coping strategies before deciding on treatments”; “need for professional care for individuals and couples with SD”; and “need for an environment that facilitates interaction among men to resolve SD issues” (Table 3).

Need for empathy from medical staff regarding fear of SD

Men commonly perceived sexual functionality to be an important condition to be a “man” and maintain their gender identity within the Japanese socio-cultural context; thus, they expressed their need for medical doctors to provide care for their SD-related identity crisis following PC treatment. However, medical doctors who provide PC treatment in Japanese hospitals are commonly careless about patients’ gender identity crises; they focus on curing cancer and extending life and tend to neglect their patients’ other needs.

I cried when the doctor told me that the treatment would make it impossible for me to have children. I could not ask the doctor any more questions because he said the treatment would cure my cancer. He indicated that life extension, not sex, should be the top priority for cancer patients. (EBRT)

Some medical doctors even make harmful comments regarding patients’ sexual functionality, showing disrespect for their gender identity.

When I searched for the effects of CAB on sexual function on the Internet and told my doctor about it, he said, “At your age, you don’t need it.” Medical institutions are responsible for curing [the] body. But when it comes to issues between the body and mind, they say, “Don’t talk to us because we are too busy.” So even if I wanted to ask questions about SD, I couldn’t. (CAB)

A serious gap exists between medical doctors’ priorities and patients’ needs, which increases patients’ suffering.

Nurses could be an alternative path for patients in seeking mental care and support; however, this route is also restricted because of the gender-related context; men-to-women sexual conversation may be perceived by women as sexual harassment. Since nurses are usually women, male patients fear talking to nurses about their SD gender identity crisis.

I hesitate to discuss sexual problems with nurses, mostly female. I fear they might take it as sexual harassment and despise me. (Prostatectomy)

Patients need care for their SD-related gender identity crisis; however, healthcare professionals’ limited knowledge of patient needs and mental health, their disrespectful attitudes, and the taboo nature of men-to-women sexual conversation are barriers to gender identity crisis care. To remove these barriers, participants insisted that healthcare professionals increase their awareness of patients’ gender identity issues and be willing to discuss patients’ sexual life and help them improve its quality.

I would like nurses to honor the patient’s values when they talk about sexual concerns. (CAB)

Healthcare providers should ask, “How do you feel when you have sex? What do you do when you have trouble getting an erection?” I would be more likely to share my concerns if they asked me, “What are you feeling during sex?” (Prostatectomy)

Need for information that provides an accurate understanding of SD and coping strategies before deciding on treatments

Participants identified a need for information; they recognized that to overcome an SD-related identity crisis, they must decide on treatment methods based on an accurate understanding of treatment-induced SD and how to manage it. However, in Japan, this type of information is not always provided to patients, who must choose from multiple treatment options. The information provided by medical institutions is biased toward treatments that the institution specializes in, since it is left to the discretion of the physician. Detailed explanations of all treatment options are not provided, which forces patients to choose treatments without knowing how each will affect their sexual function.

It would be good if the doctor explained the pros and cons of surgery, external-beam radiation, and brachytherapy when selecting treatment. (Prostatectomy)

Additionally, healthcare providers sometimes avoid negative language and offer euphemisms, which may prevent patients from accurately assessing their SD risk before treatment, making treatment decisions more difficult. This may even cause patients definitive distress from which they may not recover after treatment.

Before the surgery, the doctor explained that I would no longer be able to have children. After the surgery, I understood the doctor meant that I would not be able to get an erection, have sperm, or have children because I would become impotent. I suffered so much that I considered seeing a psychiatrist. (Prostatectomy)

Before the treatment, the doctor explained to me that it was the same as castration, but I had no idea what that meant. I was very worried that I would never be able to get an erection or ejaculate again and might lose my sex life, an important part of my daily life. Castration is a term used for dogs and cats. I was treated like an animal and could not ask the doctor anything. I tried to convince myself that, to move forward, I needed to be prepared to never have sex again and that I would not need my sexual function once my cancer was cured! (LDR)

Further, in Japanese society, sexuality is focused solely on reproduction; this fosters indifference regarding SD in the elderly, who constitute the majority of PC patients. Consultation services and resources for patients seeking information outside of medical institutions are overwhelmingly lacking.

There are few books on PC. I can only get information from the Internet. Only one Internet bulletin board focused on SD. I tried talking openly about my illness to anyone. But I could not get the necessary information about SD. (LDR)

Thus, patients are left with no information on how to cope with SD after treatment.

I want to know about medications and surgery to treat SD and their costs. (Prostatectomy)

I like to know whether there are any good ways to deal with marital dysfunction and other marital problems. (CAB)

Patients know that accurate information before treatment will help them determine the best treatment for their needs. However, the reproduction-oriented Japanese view of sexuality, physician discretion, and deductive information lead to treatment decisions that patients regret. To remove these barriers, participants argued that they need information that promotes an accurate understanding of SD and potential coping strategies before making treatment decisions.

I think the doctor needs to explain in clear terms before treatment, “If you have surgery, you will become impotent and will no longer be able to have sex.” Then patients will understand that they will not be able to have sex. That way they can work on adapting to their changed bodies after treatment. (Prostatectomy)

Need for professional care for individuals and couples with SD

Participants’ SD-related identity crises were exacerbated by partners who did not understand the distress of SD and the change in intimate relationships owing to the loss of intercourse, which requires professional care.

My wife did not understand my desire to preserve my sexual function, and our marriage became a wake-up call. With professional intervention, I believe I would have been able to move forward in my relationship with my wife, including deciding on a course of treatment. (Prostatectomy)

My girlfriend told me that she didn’t want a man who couldn’t get an erection, and I was too shocked to talk to anyone about it, so I gave up on remarriage (CAB).

Men sought support in the hope that they and their partner could adapt to changes in their sexual life by applying coping strategies they had developed in their previous joint lives.

Each treatment produces distinct symptoms. Each person has different values. Sexuality is personal. Each patient’s relationship with his wife is also unique. Each couple has built up individual coping strategies over the years. Those strategies deserve respect. (EBRT)

Need for an environment that facilitates interaction among men to resolve SD issues

Participants stated that they could not publicly discuss their SD nor could they expect help from medical professionals, leaving them with no solution for various related conflicts.

Unlike visual or hearing impairments, SD is a taboo subject and must be resolved in private. (LDR)

Even medical professionals cannot solve an individual’s sexual problems. I must manage my sexual functioning problems on my own. (LDR)

These experiences have also revealed the need for a place to feel private and safe to talk about their concerns, sort out their feelings, and interact with others with the same problems, to gain insight from others’ experiences.

I think it would be good to have a place where people can discuss their sexual issues. It will help them sort out their feelings by speaking out. They hear other people’s opinions and realize that they share similar feelings. (CAB)

I think we need a place where people can exchange opinions anonymously without experiencing abuse, harassment, or irresponsible behavior. (Prostatectomy)

Discussion

This study explored care needs for SD associated with PC treatment among Japanese men in the gender-related socio-cultural context of Japan, where sexual functionality is a key constituent of male identity, but sexual topics are taboo, even in healthcare settings. Participants identified four care needs from their experiences, summarized as empathy from medical staff regarding SD fears; accurate information to facilitate treatment decisions; professional care for individuals and couples with SD; and an environment that facilitates interaction among men to resolve SD issues. Discussing these needs can help caregivers understand patient experiences more precisely and develop ways to improve patient care.

Medical professionals need to empathize with patients’ fear of sexual dysfunction

Participants spoke of medical professionals’ lack of involvement in their suffering from SD. Nursing is an interpersonal process [21]. When nurses and patients recognize each other as unique, empathy for the other emerges, which is enhanced by each person’s desire to understand the other. When a nurse wishes to alleviate the cause of the patient’s suffering, empathy develops into sympathy, which allows the nurse to provide the knowledge-supported skills necessary to involve the person. Healthcare providers are not motivated to understand men’s experiences with SD because talking about sex embarrasses them, and they are biased about older adults’ sexuality, especially older adults with cancer [22]. Healthcare providers need proper education to empathize with their patients’ SD fears and recognize their sexual feelings, values, and behaviors. However, most nursing colleges in Japan do not offer human sexuality courses [23]. Education that is systematized to encourage healthcare professionals to empathize with patients’ SD fears would help achieve this goal.

Information is crucial to understanding sexual dysfunction and potential coping strategies before deciding on treatments

Participants noted that they lacked the necessary information about SD when deciding on PC treatment. The basic bioethics philosophy, introduced in Japan in the 1980s, advocates for respecting medical recipients’ value judgments. Frye emphasizes that autonomy is an ethical principle in nursing, asserting that the amount of information provided to make an informed choice is an external condition of autonomy [24]. However, in Japan, patients do not receive satisfactory explanations on all treatment options and are only informed of the treatment options that their medical institution specializes in. Patients do not uniformly blame medical institutions for not providing sufficient information; although they feel frustrated with their post-treatment SD, they are forced to acknowledge that their lives have been saved, and they must pay the medical institution for their services. Patients need explanations to visualize their SD and post-treatment life, understand coping strategies, and thoroughly examine treatment options.

Patients with sexual dysfunction and their partners require professional care

Participants stated that they needed to consult with competent professionals to address their diverse and personal concerns about SD. The lack of SD medical care and information has caused patients to lose intimacy with their partners. Wright et al. [25] noted that therapeutic discussions with family members about their expressed beliefs help them recognize or reaffirm their strengths and find solutions to their suffering. Individual consultation based on therapeutic conversation allows for resolution through the forces nurtured in the couple’s history. Japan has few sex therapists or sex counselors [26]. The government has asserted the need to create new occupations and task forces to support the increasing number of cancer patients [27]. Training sexuality specialists and creating sexuality-related medical teams so that patients and medical professionals can discuss difficult sexuality-related issues may be necessary.

Patients need an environment that facilitates interaction to address sexual dysfunction issues

Participants experienced loneliness when dealing with SD and needed peer support to help resolve their issues. Peer support helps resolve the sexual needs of men with PC and their partners’ sexual adjustment [28]. However, peer support does not function well in Japan, where public discussion of sexuality is not permitted.

In Japan’s Edo period, sex was a sign of the bond between heaven and earth and was considered beneficial for longevity [29]. The pursuit of sex and pleasure was viewed positively, as seen in customs such as night crawling, young men’s lodgings, girls’ lodgings, and shunga (spring pictures). However, the Meiji government, fearing that this culture would be seen as a national disgrace and that the country would be weakened by the spread of venereal diseases, enacted regulations to control sexual mores. People began to monitor each other, and the view that sex was something to be ashamed of and suppressed spread rapidly. Comprehensive sex education, which was introduced in the 1970s, has not penetrated this barrier; sex education in schools still lags behind. This historical and cultural background may contribute to PC patients’ loneliness in Japan. Comprehensive sexuality education is aimed at achieving health, happiness, and dignity, fostering respectful social and sexual relationships, considering how our choices affect our own and others’ well-being, and understanding and ensuring the protection of our rights throughout life [30]. As education is based on these guidelines’ advances, the Japanese public will begin to understand that everyone has the right to the best possible health, happiness, and well-being regarding sex, including enjoyable, satisfying, and safe sexual experiences.

This understanding will change the perception of sex as something to be ashamed of and suppressed to one in which sex is a human right and should be protected. We believe it will also change the way people think and act and promote exchanges to address the SD issue.

Reflexivity

Some participants may have remained silent about important sexual issues because the interviewer was a woman and health professional. Our analysis and interpretation may be particularly strict on medical professionals because we are a specialized group of oncology nurses.

Conclusion

This is the first study to explore the care needs of Japanese men for SD associated with PC treatment in the socio-cultural context of Japan. The findings identified the need for healthcare providers’ empathetic attitude, better information regarding PC treatments and their effects on sexual life, potential coping strategies, professional care for couples, and peer interaction regarding SD. Our study findings may facilitate care strategies tailored to these needs. Comprehensive sex education is needed to fully address patient care needs.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL et al (2021) Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71(3):209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research (2021) Cancer statistics in Japan 2021. Available from: https://ganjoho.jp/public/qa_links/report/statistics/pdf/cancer_statistics_2021.pdf .

Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V et al (2018) Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000–14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet 391(10125):1023–1075. https://doi.org/10.1016/2FS0140-6736(17)33326-3

Muermann MM, Wassersug RJ (2022) Prostate cancer from a sex and gender perspective: a review. Sex Med Rev 10(1):142–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2021.03.001

Hayashi S, Fumiko O, Kazuki S et al (2022) Sexual dysfunction associated with prostate cancer treatment in Japanese men: a qualitative research. Support Care Cancer. 30:3201–3213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06728-2

Chambers SK, Hyde MK, Smith DP et al (2017) New challenges in psycho-oncology research III: a systematic review of psychological interventions for prostate cancer survivors and their partners: clinical and research implications. Psycho-Oncol 26(7):873–913. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4431

Latini DM, Hart SL, Coon DW et al (2009) Sexual rehabilitation after localized prostate cancer current interventions and future directions. Cancer J 15(1):34–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/2FPPO.0b013e31819765ef

Neff K (2003) Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2(2):85. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Lennon J, Hevey D, Kinsella L (2018) Gender role conflict, emotional approach coping, self-compassion, and distress in prostate cancer patients: a model of direct and moderating effects. Psycho-Oncol 27(8):2009–2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4762

Bossio JA, Miller F, O'Loughlin JI, Brotto LA (2019) Sexual health recovery for prostate cancer survivors: the proposed role of acceptance and mindfulness-based interventions. Sex Med Rev 7(4):627–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.03.001

Collaco N, Wagland R, Alexis O, Gavin A, Glaser A, Watson EK (2021) The experiences and needs of couples affected by prostate cancer aged 65 and under: a qualitative study. J Cancer Surviv 15(2):358–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00936-1

Sakai K, Mizuno M, Hamamoto Y et al (2012) Sexuality as an aspect of nursing care for prostate cancer patients and the awareness of nurses providing such care. J Jpn Soc Nurs Res 35(4):57–64

Hayashi S, Oishi F (2018) A literature review on sexual dysfunction in patients receiving treatment for prostate cancer. Annu Rep Res Inst Life Health Sci 14:81–91

Takahashi M, Kai I, Hisata M, Higashi Y (2006) Attitudes and practices of breast cancer consultations regarding sexual issues: a nationwide survey of Japanese surgeons. J Clin Oncol 24(36):5763–5768. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2006.06.9146

Tan HM, Marumo K, Yang DY et al (2009) Sex among Asian men and women: the global better sex survey in Asia. Int J Urol 16(5):507–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02283.x

Moreira ED Jr, Brock G, Glasser DB et al (2005) Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract 59:6–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00382.x

Tanaka T (2015) Being a man is hard: men’s studies of hope in the midst of despair. Kadokawa Publishing Company, Tokyo. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB18866560

Flick U, Oda H (2011) Qualitative Sozialforschung. Shunjusha Publishing Company, Tokyo. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB05058687

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6):349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Berelson B, Inaba M (1957) Content analysis. Social psychology course. Vol. 7 Mass communication with the masses 3. Misuzu Shobo, Ltd, Tokyo. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BN09286746

Travelbee J (1971) Interpersonal aspects of nursing. F.A, Davis, Philadelphia. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA39319376

Hayashi S, Oishi F, Ando S (2021) Two conflicting attitudes of nurses and their backgrounds in support for sexual dysfunction associated with prostate cancer treatment. J Jpn Soc Cancer Nurs 35:187–197

Mizuno M, Fukuda H (2009) Education on sexuality in the basic nursing education course: analysis of syllabi. Matern Health 49(4):612–619

Frye ST, Johnstone MJ (2010) Ethics in nursing practice: a guide to ethical decision making (2010). Japan Nursing Association Publishing Company Ltd., Tokyo. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB01730655

Wright LM, Watson WL, Bell JM/Sugishita T (2002) Beliefs: the heart of healing in families and illness. Japanese Nursing Association Publishing Company, Ltd., Tokyo. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA5683047X

Japan Society of Sexual Science. List of sex counselors and therapists (2021) https://sexology.jp/counselors_list/. Accessed 9 June 2022

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Cancer control promotion basic plan (2018) https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10900000-Kenkoukyoku/0000196975.pdf. Accessed 9 June 2022

Chambers SK, Occhipinti S, Stiller A et al (2019) Five-year outcomes from a randomised controlled trial of a couples-based intervention for men with localised prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 28(4):775–783. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5019

Frühstück S (2003) Colonizing sex: sexology and social control in modern Japan. University of California Press, Berkeley. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BC07954153

Unesco/Haruo Asai, Ushitora K, Tashiro M et al (2020) International technical guidance on sexuality education An evidence-informed approach. Akashi Publishing Company, Tokyo. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BC01688636

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to the patients who agreed to participate in this study and generously provided valuable information. We also express our sincere appreciation to all concerned for their understanding of this study and the many arrangements and accommodations they made to provide a research venue and facilitate its smooth progress. We also thank Dr. Makoto Endo at Endoiin for collaboration during the early stages of this work and for useful discussions. We are grateful to Ms. Tae Hasegawa at Miyakojima iGRT Clinic for collaboration during the early stages of this work.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant number [JP20K10773].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Saeko Hayashi, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Nagoya University (March 13, 2020/No. 19-151).

Consent to participate

Verbal and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Participants provided consent to use anonymous quotes for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hayashi, S., Sato, K., Oishi, F. et al. Care needs of Japanese men for sexual dysfunction associated with prostate cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 31, 378 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07837-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07837-w