Abstract

Rationale

Patient support lines (PSLs) assist in triaging clinical problems, addressing patient queries, and navigating a complex multi-disciplinary oncology team. While providing support and training to the nursing staff who operate these lines is key, there is limited data on their experience and feedback.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of oncology nurses’ (ONs’) perspectives on the provision of care via PSLs at a tertiary referral cancer center via an anonymous, descriptive survey. Measures collected included nursing and patient characteristics, nature of questions addressed, perceived patient and nursing satisfaction with the service, common challenges faced, and initiatives to improve the patient and nursing experience. The survey was delivered online, with electronic data collection, and analysis is reported descriptively.

Results

Seventy-one percent (30/42) of eligible ONs responded to the survey. The most common disease site, stage, and symptom addressed by PSLs were breast cancer, metastatic disease, and pain, respectively. The most common reported issue was treatment-related toxicity (96.7%, 29/30). Sixty-seven percent (20/30) of respondents were satisfied with the care provided by the service; however, many areas for potential improvement were identified. Fifty-nine percent (17/29) of respondents recommended redefining PSLs’ responsibilities for improved use, with 75% (6/8) ONs identifying high call volumes due to inappropriate questions as a barrier to care. Sixty percent (18/30) of ONs reported having hospital-specific management plans for common issues would improve the care provided by the PSL.

Conclusion

Despite high rates of satisfaction with the care provided by the PSL, our study identified several important areas for improvement which we feel warrant further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since their establishment in 1975, patient support lines have been a valuable resource in answering and triaging non-urgent patient medical queries and providing emotional support as patients and caregivers navigate life-changing diagnoses and interact with a complex multi-disciplinary oncology team [1]. Patients have reported on the positive impact of access to familiar nursing staff and expedited follow-up with oncologists facilitated by support lines [2]. As such, it is important to provide the nursing staff that operate these lines with ongoing support and training.

Literature examining methods to improve nursing and patient experience on cancer helplines and to ensure appropriate quality control was published as early as the1980s [3]. This helped guide research on a stress-coping model to emotionally support patients through new cancer diagnoses or complications thereof [3]. Since then, several studies have detailed patient experience on support lines, the psychosocial impact of support lines and most effective communication methods [1, 4, 5]. As such, several guidelines have been developed to standardize nursing management via patient support lines or cancer helplines, including those from the College of Nurses of Ontario (CNO), Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology (CANO), and Pan-Canadian Oncology Symptom Triage and Remote Support (COSTaRS) project [6,7,8].

The Ottawa Hospital Cancer Centre (TOHCC) is an academic tertiary center providing access to specialized cancer care and clinical trials. TOHCC serves a population of approximately 1.5 million patients in Eastern Ontario, Canada, with over 25,000 visits per year [9]. The center provides care via two telephone support lines, the TOHCC patient support line (PSL) and the Wellness Beyond Cancer PSL. The TOHCC PSL was established in 2015 to assist patients with questions regarding active cancer care. It operates Monday to Friday, from 9 am to 4 pm, with the recent introduction of an after-hours and weekend service provided through a provincial nursing service (CAREchart@home). The volume of calls received by the PSL increased significantly during the pandemic, from an average of 3600 to 5200 per month. The Wellness Beyond Cancer PSL was established in 2012 to address concerns related to patients who have been discharged from the cancer center following the completion of their cancer treatment. It is available from 8 am to 4 pm, Monday to Friday [9]. Both PSLs are supported by a cohort of oncology nurses (ONs, n = 42), clerical staff. and administrative support (clinical care leader and clinical manager). One of the guidelines used by ONs who operate PSLs is the Pan-Canadian Oncology Symptom Triage and Remote Support (COSTaRS) practice guides, which were adapted to The Ottawa Hospital Cancer Centre in 2016 [10].

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in December 2019, there has been a rapid shift to virtual care and increased demand for telehealth services, one of which is patient support lines [11,12,13]. This change, in concurrence to prior literature, has highlighted the importance of providing the nursing staff operating these helplines with adequate knowledge, support, and confidence to assess and triage patients' medical and emotional concerns [14]. However, there is limited, current, data on oncology nurses’ experience and feedback on ongoing improvement strategies of patient support lines [15, 16].

In the current study, we surveyed oncology nurses (ONs) who deliver care via TOHCC and WBCP PSLs for their perspective on the quality and efficacy of care delivered via the support lines, the nature of questions asked, and issues addressed, as well as challenges faced. This data will be used to identify key areas for improvement to optimize patient and nursing experience, and the quality of care delivered by the service.

Methods

Study population

All oncology nurses (ONs) providing care via TOHCC and WBCP PSLs were included in this cross-sectional study, for a sample size of 42, with a target participation rate of 80%.

Study outcomes

The primary outcomes of the study were to learn about nurses’ experience on PSLs. In addition, we wanted to identify areas for improvement to optimize the quality of care and patient and nursing satisfaction with the service.

Survey development

The survey was developed by healthcare providers (HCPs) and researchers at the TOHCC with experience in questionnaire development and the provision of care via the PSL. It followed the structure provided by the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) outlined by Eysenbach [17] as reported in Table 1. We conducted preliminary screens within the research group and with oncology nurses to ensure the survey was functional and to eliminate any technical limitations. An introductory section explained the purpose of the survey and indicated that completion implied consent to participate. The first section of the survey consisted of 5 closed questions that confirmed eligibility and collected demographic information including years worked as an ON, years of experience providing care via TOHCC support lines, and number of days per week spent providing care on the PSL. The second section included 4 closed questions that collected data on the most common disease sites and stage encountered, and the nature of questions addressed by the service, including high-level issues and specific symptoms managed. The third section included 12 closed and 4 open questions that sought nurses’ perceptions on the quality and efficacy of care provided by TOHCC PSLs and barriers to providing the desired standard of care. Finally, nurses’ insights on potential strategies to improve the quality of care provided by the support line were explored. Thus, in total there were 21 closed questions and 4 open questions. The entire survey was presented on one screen.

Survey implementation

This was a closed descriptive survey where nurses providing care via PSLs were invited to voluntarily participate in an online survey via an email from the clinical manager of the TOHCC Clinics and Wellness Beyond Cancer Program (SN). No incentives were offered for completion of survey. The email contained a hyperlink to the electronic survey on Microsoft® Forms and an information sheet regarding the study. The Microsoft® Forms software collected, stored, and aggregated the data into a Microsoft® Excel sheet that was used for analysis. Both software programs were accessed from the hospital’s Microsoft® OneDrive to ensure data was collected and stored securely. A reminder email with the electronic survey link was sent 4 weeks later to increase participation [18, 19]. The survey was conducted between September 9, 2021, and October 8, 2021, with the reminder email sent on October 4, 2021. The survey was completed anonymously, and no personal identifiers were collected. Completion of survey was indicative of consent for analysis and publication. We did not offer completeness checks, non-response options for some of the questions, or a review step as a part of the survey. As we required completion of survey to indicate consent, we cannot offer participation or completion rates. The study and survey were approved by the Ottawa Hospital Science Network Research Ethics Board (OHSN-REB) on August 17, 2021.

Data collection and analysis

Responses were stored in a password-protected database accessible to the study team only. Data was further managed on an Excel spreadsheet and saved to a secure server at the Ottawa Hospital. Statistical analysis was completed by study staff and data will be reported descriptively. Planned analysis for open-ended questions was to present data ad verbatim as shown in the “Supplementary information” and summarized descriptively in the manuscript. No statistical correction was performed. We included all surveys that were submitted, even if respondents did not complete all questions.

Results

Participant demographics

The response rate was 71.4%, with 30 of the 42 eligible nursing staff completing the survey. Sixty-three percent (19/30) of nurses had worked as an oncology nurse for greater than 10 years. Forty-three percent (13/30) of nurses had provided care on TOHCC PSLs for less than 5 years, 37% (11/30) for 5–10 years, and 20% (6/30) for greater than 10 years. The majority (83%, 25/30) provided care via the PSL at least one day per week (Table 2).

Characteristics of support line users and calls

From nurses’ experience, the most common disease sites contacting the TOHCC PSLs are breast (60%, 18/30) and gastrointestinal cancers (40%, 12/30). When asked to rank the most common disease stage of patients using the service, 70.8% (17/24) ranked metastatic disease as the most common, followed by patients receiving adjuvant treatment for early-stage disease. Participants identified the 5 most common issues dealt with by the support line as toxicities of chemotherapy (96.7%, 29/30), requests for prescription refills or questions about drug coverage (83.3%, 25/30), cancer symptoms (66.7%, 20/30), abnormal test results (60%, 18/30), and questions about booking information (43.3%, 13/30). The 5 most common cancer- and treatment-related symptoms addressed by the PSL were identified as pain (96.7%, 29/30), nausea/vomiting (90%, 27/30), constipation/diarrhea (86.7%, 26/30), shortness of breath (70%, 21/30), and fever (30%, 9/30). Further details on questions and symptoms addressed on TOHCC PSL are detailed in Table 3.

Nursing experience on the support line

Results showed that 67% of nurses were satisfied (agree 15/30, strongly agree 5/30) with the quality and efficacy of the care they provided via TOHCC PSLs. However, 33.3% were either neutral (5/30) or expressed dissatisfaction (disagree 5/30, strongly disagree 0/30) with care provided. Patients were perceived to be satisfied with the care they received via TOHCC PSLs by 70% of nurses (agree 17/30, strongly agree 4/30), with 23.3% (7/30) being neutral and only 6.7% of nurses feeling patients were dissatisfied with the care provided (Table 4). Of the 8 nurses detailing the reason for patients’ and/or nursing dissatisfaction, high call volumes were reported to be a leading cause by 6 nurses, as it decreased the time allocated for providing support to patients and their caregivers, appropriately answering patient queries, and preventing emergency department visits. A lack of support from either management of physicians was cited by 3 nurses as a factor reducing nursing ability to answer patient queries. The frequent closure of an outpatient unit where patients could be quickly assessed by a physician was identified as a barrier to providing satisfactory care by 2 nurses, as patients then needed to be referred to the emergency department for minor issues. Finally, 1 nurse recommended that nursing staff scheduled to operate the support line on a given day have experience across different disease sites, to ensure a broader range of expertise was available to address patient needs.

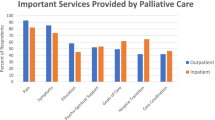

While majority of nurses agreed that the PSL was appropriately used by physicians (73%, agree 19/30, strongly agree 3/30), fewer felt that patients used the service appropriately (39.7%, agree 11/30, strongly agree 1/30) (Table 4). The top 5 appropriate uses of TOHCC PSL as per respondents were management of urgent treatment-related toxicity (96.7%, 29/30), management of cancer-related symptoms (96.7%, 29/30), and management of urgent test results, or those guiding cancer treatment (70%, 21/30), provision of emotional support (43% 13/30) and addressing medication queries (30%, 9/30). Additional responses are detailed in Table 4.

The survey found that 80% (24/30) of nurses did not feel that there was a decreased volume of calls to the PSL when patients were provided with greater access to their electronic medical record (EMR), including immediate release of test results (Table 4). Of note, all respondents noted increased anxiety and stress related to test results that were often viewed prior to appointment times leading to increased volume of calls requesting explanation of results, earlier appointments, or to speak with their oncologist sooner. Only 2 nurses felt that increased patient access to their EMR had improved the volume of calls due to patients learning the treatment plan from physician progress notes or answering their questions via chart review.

Insights on strategies to improve care

The barriers to care identified by TOHCC PSL nurses are detailed in Table 4, with the primary reason cited as high volume of inappropriate/non-urgent calls making it challenging to deal with acute issues (80%, 24/30). As such, 58.6% (17/29) nurses reported a need to redefine the goals and responsibilities of the support line to ensure appropriate use of the PSL by patients and physicians.

An alternative strategy to improve care investigated in the survey was the utility of consensus guidelines in addressing patient queries on the PSL. The majority of nurses agreed that TOHCC specific, consensus guidelines, for the management of common patient issues and symptoms such as treatment related toxicity and pain, respectively, would improve the efficacy and quality of care provided (60%, 18/30), and nursing experience (56.7%, 17/30) on the PSL. However, 36.7% nurses were unsure of their utility. To help develop these guidelines, nurses reported experience with similar established guidelines from the Pan-Canadian Oncology Symptom Triage and Remote Support (COSTaRS) project, (33.3%, 10/30), Cancer Care Ontario (CCO) (20%, 6/30), and Cancer Association of Nurses in Ontario (CANO) (3.3%, 1/30) [7, 8, 20].

Nurses were asked to rank 4 other potential interventions to improve the delivery of care via TOHCC PSLs. The intervention ranked first by majority of respondents was, “identifying issues that do not need nursing input that could be delegated to another service for management” (33%, 8/24). Of 24 respondents, 6 ONs identified the “introduction of medical directives to give nurses greater power/autonomy in patient care as appropriate” as their most important initiative. Finally, “having a TOHCC Frequently Asked Questions webpage/document to refer patients to for simple/common issues” and “having a single contact number for the cancer center to reduce duplication of calls/work” were each identified by 20% of respondents (5/24) respectively, as the most important initiative to improve care via the PSL. Details of second and later choices are reported in Table 5.

Alternative potential improvement strategies proposed by nursing respondents were increased training for clerks operating PSLs, physician consensus, and patient education in appropriate use of the PSL, increased staff on high volume days, improved quality of TOHCC website, and the introduction of nurse-led clinics to further support patients. The recommendations from nurses are detailed in Table 6.

Discussion

Cancer support lines provide a critical service to patients and caregivers, helping them to navigate complex diagnoses, treatment plans, and healthcare systems, while providing important psychosocial support [1, 21,22,23]. The TOHCC and WBC PSLs were created with the aim to address these areas of patient care. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increased demand for the service, which served as an important way to help immunocompromised cancer patients maintain social distancing and reduce their contact with high-risk clinical environments [24].

There has been much research to date on nursing directed care via PSLs and other telehealth initiatives to manage symptoms in cancer patients. Despite their widespread use, a recent Cochrane systematic review of randomized studies of nursing-led telephone interventions for symptom control in cancer patients could not confirm the effectiveness of these interventions due to a lack of high quality, standardized data, with additional research in the field highlighted as a priority [25]. However, other studies have reported on the benefits of PSLs [26, 27], with additional areas of study including characteristics of calls received [28, 29], best practices for training of care providers [30,31,32], and patient perspectives on services provided [33, 34]. There is, however, limited data on nursing feedback on their experience and initiatives to improve the service. Furthermore, most of the research was conducted before the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which has seen a significant increase in demand for remote/virtual healthcare including PSLs. Our study adds to data on nursing-led PSLs by providing ON perspectives on the delivery of care, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Overall, nursing and perceived patient satisfaction with TOHCC and WBC PSLs was high. However, several areas for improvement were reported, such as high volume of inappropriate calls and time constraints with each call, with recommendations to consider redefining the responsibilities of the PSL to patients and physicians, identify issues that could be delegated to non-nursing staff and develop TOHCC-specific PSL management guidelines. The knowledge gained from this survey will be used to develop initiatives to improve the care provided by our service and may be applied to cancer support lines in other institutions.

Firstly, it identified the most common disease site, stage, and symptoms addressed by the PSL which would be important areas for ongoing nursing training and education. Interestingly, despite the availability of numerous cancer symptom management guidelines [8, 18, 35, 36], which nurses were familiar with, and the existing integration of COSTaRs in the EPIC EMR system at TOHCC, there was still keen interest in developing hospital specific guides for the management of common issues, to incorporate local practices and needs. Given the significant research directed toward the development of the aforementioned standardized guidelines, we feel this is an important finding warranting further investigation to determine what specific needs nurses feel are not addressed by existing guidelines.

The study also identified other potential parties for education, namely, physicians, patients, and administration, to ensure PSL services are used appropriately and to their maximum potential. Indeed, many nurses supported redefining the goals and responsibilities of the PSL to ensure nurses were dealing with appropriate clinical, rather than clerical or administrative issues. On review of the literature, this has not been commonly addressed as an area for optimization, with previous reviews instead focusing on variability in patient access and comfort with technology to support remote/virtual healthcare, limited telemedicine modalities used, few nursing training opportunities, and funding, as potential areas of optimization [37, 38] As such, we believe this as an area requiring further research to ensure PSLs have clearly defined goals, with optimal administrative and managerial support and setup.

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a rapid shift to remote/virtual care, including telehealth, by all healthcare providers including nurses, directed by clinical practice guidelines, such as ASCO’s guide to cancer care delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic [39]. Paterson et al. conducted a literature review examining the role of telehealth during the pandemic across disciplines, reporting increased use of telehealth, support lines, and EMR systems during the pandemic with limitations including lack of physical assessments, poor electronic literacy, and access to smart devices, amongst others [11]. Margolius et al. supported this and reported increased use of PSLs for COVID-19-related concerns, and their importance in providing ongoing rapid and efficient care despite pandemic restrictions [13]. Similarly, Nath et al. reported increased use of inbox messaging and EMRs to contact physicians across different specialties in an ambulatory clinic setting in the context of the pandemic [12]. Interestingly, our nursing respondents did not feel that patients having increased access to their EMR reduced calls to the support line. Rather, it was perceived by nurses as a source of increased calls due to patient stress and anxiety related to the information provided, which often required medical expertise in understanding or interpreting. A review of literature does not however support this claim. While several studies note HCPs’ perception of increased patient anxiety and call volumes due to difficulty with data interpretation with increased EMR access among patients, most studies did not find this to be the case and the call volumes did not change significantly [40,41,42,43]. This highlights the need for better education amongst healthcare providers on the benefits of patient EMR access and the development of initiatives to better use medical record systems to support, guide and communicate with patients. This will be increasingly important as the role of virtual care develops and expands during, and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are however limitations to our data. It is a single-center study, and despite the overall high response rate, there were some incomplete responses that may have limited the perspectives gained. However, in this case, we do not think it would have changed the results, and we have reviewed the questions to help inform future surveys to ensure questions and design are clear to minimize any potential barriers to response. Similarly, some of the questions with “other” as an option could have been followed with an open-ended question or comment section to capture more information. Our question on quality or efficacy did not delineate between the two, but given a broad consistency across responses, we suspect that the ONs interpreted the question accurately. Additionally, we are lacking feedback from patients and physicians regarding their experience of, and expectations for PSLs, which would offer a more comprehensive assessment of the service, and initiatives to improve the care provided. Furthermore, we did not collect data points on age, sex, oncology nursing certification, or level of nursing education, which may have provided additional information on demographics and diversity. Finally, our study would benefit from analyzing our data in combination with variance in call volumes to identify innovative solutions for times when the demand for the service is high, e.g., post weekends or holidays. These areas will however be the focus of future research efforts, as we strive to optimize the potential of this critical patient service.

Conclusion

Despite high rates of ON, and perceived patient satisfaction with the care provided by the PSL, there was a clear need for improvement in several areas, such as high call volumes and time constraints. Our study also identified TOHCC-specific algorithms adapted from international and Canadian guidelines to guide management of common issues addressed by the PSL as a potential strategy to improve care. Furthermore, there is ongoing need for improved strategies to better incorporate EMRs in patient care. These findings will inform future initiatives to improve the delivery of care via TOHCC support lines and may be applicable to cancer support lines at other centers.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request with approval of the Ottawa Hospital Science Network Research Ethics Board.

References

Clinton-McHarg T et al (2014) Do cancer helplines deliver benefits to people affected by cancer? A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 97(3):302–309

Stacey D et al (2016) Patient and family experiences with accessing telephone cancer treatment symptom support: a descriptive study. Support Care Cancer 24(2):893–901

Bramwell L (1989) Cancer nursing-a problem-finding survey. Cancer Nurs 12(6):320–328

Leydon GM et al (2013) “How can I help?” Nurse call openings on a cancer helpline and implications for call progressivity. Patient Educ Couns 92(1):23–30

Woods CJ et al (2015) Closing calls to a cancer helpline: expressions of caller satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns 98(8):943–953

College of Nurses of Ontario (2020) Telepractice Practice Guideline. https://www.cno.org/globalassets/docs/prac/41041_telephone.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2022

Stacey D, for Pan-Canadian Oncology Symptom Triage and Remote Support (COSTaRS) Team (2020) Remote Symptom Practice Guides for Adults on Cancer Treatments. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cano-acio.ca/resource/resmgr/files/costars_2020_en.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2022

Stacey D et al (2020) Pan-Canadian Oncology Symptom Triage and Remote Support (COSTaRS) practice guides - what’s changed in Version 2020? Can Oncol Nurs J 30(4):269–276

Leydon GM et al (2019) Specialist call handlers’ perspectives on providing help on a cancer helpline: a qualitative interview study. Eur J Cancer Care 28(5):e13081

Jibb LA et al (2019) Research priorities for the pan-Canadian Oncology Symptom Triage and Remote Support practice guides: A modified nominal group consensus. Curr Oncol 26(3):173–182

Paterson C et al (2020) The role of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic across the interdisciplinary cancer team: implications for practice. Semin Oncol Nurs 36(6):151090

Nath B et al (2021) Trends in electronic health record inbox messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic in an ambulatory practice network in New England. JAMA Netw Open 4(10):e2131490–e2131490

Margolius D et al (2021) On the front (phone) lines: results of a COVID-19 hotline. J Am Board Fam Med 34:S95–S102

Stacey D et al (2015) Training oncology nurses to use remote symptom support protocols: A retrospective pre-/post-study. Oncol Nurs Forum 42(2):174–182

Heckel L et al (2019) Are cancer helplines effective in supporting caregivers? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer 27:3219–3231

Rushton M et al (2015) Wellness beyond cancer program: building an effective survivorship program. Curr Oncol 22(6):419–434

Eysenbach G (2004) Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 6(3):34

McPeake J et al (2014) Electronic surveys: how to maximise success. Nurse Res 21(3):24–26

Sammut R et al (2021) Strategies to improve response rates to web surveys: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud 123:104058

Cancer Care Ontario (2021) Managing Symptoms, Side Effects & Well-Being. https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/symptom-management. Accessed January 20, 2022

Carlson LE et al (2012) Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol 30:1160–1177

Holland J, Reznik I (2005) Pathways for psychosocial care of cancer survivors. Cancer 1.104(11 Suppl):2624–37

Dumont S et al (2006) Caring for a loved one with advanced cancer: determinants of psychological distress in family caregivers. J Palliat Med 9:912–921

Curigliano G et al (2020) Managing cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: an ESMO multidisciplinary expert consensus. Ann Oncol 31(10):1320–1335

Ream E, et al. (2020) Telephone interventions for symptom management in adults with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6.6:CD007568

Torres-Vigil I et al (2021) The role of empathic nursing telephone interventions with advanced cancer patients: a qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 50:101863

Zhang Q et al (2018) Effects of nurse-led home-based exercise & cognitive behavioral therapy on reducing cancer-related fatigue in patients with ovarian cancer during and after chemotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 78:52–60

Flannery M et al (2009) Examining telephone calls in ambulatory oncology. J Oncol Pract 5(2):57–60

Nail LM et al (1989) Nursing care by telephone: describing practice in an ambulatory oncology center. Oncol Nurs Forum 16(3):387–395

Ciccolini K et al (2022) Oncology nursing telephone triage workshop: impact on nurses’ knowledge, confidence, and skill. Cancer Nurs 45(2):E463–E470

Gleason K et al (2013) Ambulatory oncology nurses making the right call: assessment and education in telephone triage practices. Clin J Oncol Nurs 17(3):335–336

Sevean P et al (2008) Bridging the distance: educating nurses for telehealth practice. J Contin Educ Nurs 39(9):413–418

Stacey D. et al. (2020) Quality of telephone nursing services for adults with cancer and related non-emergent visits to the emergency department. Can Oncol Nurs J 30.3:193–199

Liptrott S et al (2018) Acceptability of telephone support as perceived by patients with cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care 27(1):10

NCCN Guidelines. Supportive Care (2020) https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_3. Accessed January 20, 2022

Oncology Nursing Society (2017) Acute pain. https://www.ons.org/pep/acute-pain. Accessed January 2, 2022

Prasad A et al (2020) Optimizing your telemedicine visit during the COVID-19 pandemic: practice guidelines for patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 42(6):1317–1321

Chan RJ et al (2021) The efficacy, challenges, and facilitators of telemedicine in post-treatment cancer survivorship care: an overview of systematic reviews. Ann Oncol 32(12):1552–1570

American Society of Clinical Oncology (2021) ASCO special report: a guide to cancer care delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/2020-ASCO-Guide-Cancer-COVID19.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2022

Rodriguez E et al (2011) Nurse and physician perspectives on patients with cancer having online access to their laboratory results. Oncol Nurs Forum 38:4

Alpert JM et al (2018) Implications of patient portal transparency in oncology: qualitative interview study on the experiences of patients, oncologists, and medical informaticists. JMIR Cancer 4(1):e8993

Rexhepi Hanife, et al. (2018) Cancer patients’ attitudes and experiences of online access to their electronic medical records: a qualitative study. Health Informatics J 24.2:115–124

Gerber DE et al (2017) Oncology nursing perceptions of patient electronic portal use: a qualitative analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum 44(2):165–170

Funding

This work was supported by the Rethinking Clinical Trials (REaCT) program at the Ottawa Hospital, which is supported by The Ottawa Hospital Foundation and its donors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HS, LV, FM, GL, MC, and SMG designed the survey. LV created the online version of survey. HS, LV, MC, and SMG prepared the protocol. SN e-mailed the survey to participants. HS did the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of data analysis. All authors were involved in the critical review of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent to participate

Participation and completion of the survey implied consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Participation and completion of the survey implied consent to publication of aggregate survey findings.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, H., Vandermeer, L., MacDonald, F. et al. Delivery of cancer care via an outpatient telephone support line: a cross-sectional study of oncology nursing perspectives on quality and challenges. Support Care Cancer 30, 9079–9091 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07327-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07327-5