Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to better understand the patient perspective and treatment experience of relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM).

Methods

This qualitative study enrolled adult RRMM patients from 6 US clinics who had ≥ 3 months of life expectancy, ≤ 6 prior lines of therapy, and ≥ 1 treatment regimen with a proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulator, or a CD38 monoclonal antibody or an alkylating agent, and a steroid. In-person semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted to capture concepts that were relevant and important to patients. Topics included RRMM symptoms and impacts and the mode of administration, frequency, duration, convenience, side effects, and overall experience with RRMM treatment.

Results

A total of 22 patients completed interviews. At enrollment, 59.1% of participants were using regimens containing dexamethasone, 36.4% daratumumab, 27.3% carfilzomib, and 18.2% lenalidomide. More participants had experience using intravenous or injectable therapy alone (40.9%) than oral therapy alone (18.2%). Back pain and fatigue were the most frequently reported symptoms (40.9% each); 27.3% reported no symptoms. Most participants reported physical function limitations (86.4%), emotional impacts (77.3%), MM-related activity limitations (72.7%), and sleep disturbances (63.6%). Most participants perceived treatment effectiveness based on physician-explained clinical signs (68.2%) and symptom relief (40.9%). Participants experienced gastrointestinal adverse events (59.1%), fatigue (59.1%), sleep disturbances (31.8%), and allergic reactions (31.8%) with treatment. Key elements of treatment burden included the duration of a typical treatment day (68.2%), treatment interfering with daily activities (54.5%), and infusion duration (50.0%).

Conclusions

These results provide treatment experience–related data to further understand RRMM treatment burden and better inform treatment decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a clonal plasma cell malignancy with an incidence of 7.1 per 100,000 persons in the USA that was projected to account for an estimated 34,920 new cases (1.8% of all new cancer cases) and 12,410 deaths (2.0% of cancer deaths) in the year 2021 [1, 2]. It is the second most common hematological malignancy (10%) after non-Hodgkin lymphoma [3]. The typical age of onset in the USA is between 65 and 74 years [2], and the global incidence of MM is increasing [4], driven by factors such as the growing aging population, improved diagnostic capabilities, and increased awareness [5, 6]. Multiple myeloma is associated with significant morbidity and mortality characterized by impaired immune function, bone destruction, end-organ damage including renal failure, and death [4, 7].

Existing and emerging MM therapies, including proteasome inhibitors (PI), immunomodulators (IMiDs), and monoclonal antibodies, have dramatically improved median survival and 5-year survival rates in the past two decades [8,9,10]. Although the development of targeted therapies has improved treatment outcomes in patients with MM, most patients eventually relapse or become refractory to treatment [11]. Modern therapies have improved survival outcomes for patients with relapsed and/or refractory MM (RRMM), but prognosis is still poor [9, 12, 13]. Patients with RRMM require long-term treatment and an increased frequency of hospital and clinic visits, which is associated with indirect costs (e.g., time spent in hospital/clinic) and financial burden [14]. The increasing number of novel therapies and changing MM treatment goals have also increased the complexity of managing RRMM, as healthcare providers must consider patient-, disease-, and treatment-related factors as well as individual patient preferences when selecting treatments [11, 14,15,16].

More knowledge about patient experiences with treatments and their impact on everyday activities, including health-related quality of life (HRQOL), is needed for healthcare providers and patients to make informed treatment decisions [16,17,18]. This study aimed to gain a better understanding of the patient perspective on disease symptoms and impact and treatment experience with managing RRMM.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a qualitative study of adult patients (≥ 18 years) in the USA with RRMM. Eligible patients had at least 1 prior MM relapse, a physician-confirmed life expectancy of at least 3 months, and were not eligible for stem cell transplant at the time of enrollment. Patients were eligible to enroll with up to 6 lines of prior therapy; the initial protocol included patients with up to 3 lines of prior therapy, but a protocol amendment of up to 6 lines was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) to facilitate broader patient recruitment. Eligible patients had received at least 1 regimen with a PI and IMiD, or a CD38 monoclonal antibody or an alkylating agent, and a steroid. Patients were also required to be able to read, write, speak, and understand English. Patients who had received stem cell transplant following relapse, had been diagnosed or treated for another malignancy within 2 years before MM diagnosis, or had any evidence of residual disease from a previously diagnosed malignancy were excluded. Patients were also excluded if they were diagnosed with a clinically relevant medical or psychiatric condition that could interfere with completing the study or had an uncontrolled/active infection or concurrent medical condition with symptoms that could confound their description of their experience with RRMM.

Purposeful sampling was used to enroll patients with RRMM from 6 community-based oncology clinics located in New York, Ohio, California, and Maryland. The participating sites were selected based on their expected ability to recruit eligible patients within the needed timeframe. Sites identified potential patients by screening medical records and databases to abstract key variables such as disease background and current treatment regimen. Potentially eligible patients were then contacted by phone or in person by site personnel using a prepared script summarizing the goals of the study and inviting them to participate in a one-time face-to-face interview. If the patient was interested, the site began the informed consent process. All participants provided written informed consent and agreed to the audio-recording and transcription of the interview. The site staff then abstracted additional descriptive demographic data about participants from the patient medical records. The study protocol was approved by Advarra IRB (Columbia, MD). Participants were compensated for time spent with a prepaid cash card presented in person at the end of the interview session.

Qualitative interviews

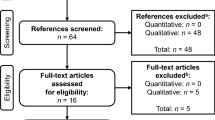

Prior to conducting the RRMM patient interviews, we completed a targeted literature review and formative/pilot discussions with MM expert clinicians (n = 5) and patients (n = 3) to identify a list of concepts used to describe disease- and treatment-related experiences (Supplemental Fig. S1). This preliminary conceptual framework was used to guide the development of the semi-structured qualitative interview guide used in the RRMM patient interviews.

Study participants with RRMM were scheduled for an in-person concept elicitation (CE) interview in a private and comfortable setting at the clinic site. Each interview lasted 60 to 75 min. The interviewer used a semi-structured interview guide with follow-up probes when needed to capture the concepts that were relevant and important from the patient perspective and to conceptualize the symptoms, impacts (including physical, emotional, sleep, social, and functioning in daily life), treatment experiences, and treatment burden of RRMM.

An iterative approach was used to conduct two sets of interviews. Version 1 of the interview guide included questions involving the symptoms and impact of the disease in addition to participants’ treatment experiences. The interviews started with questions about symptoms participants experienced prior to being diagnosed with RRMM; then asked about symptoms they experienced during treatment, including whether there were any changes in their pre-diagnosis symptoms after treatment was initiated; and finally asked about impacts and treatment burden. In the initial wave of interviews, the research team observed patients’ emphasis on the burden of treatment. Hence, in the next wave of qualitative interviews, the research team focused more deeply on evaluating the treatment burden and benefit concepts that are relevant to patients with RRMM. Version 2 of the interview guide used targeted questions regarding the mode of administration, the frequency and duration of treatment, the overall convenience of receiving MM treatment, and the side effects of treatments. Questions focused on the convenience of MM medications and possible interference with daily activities and other factors leading to a favorable or unfavorable experience with treatment. Specific questions about the participant’s overall experience with treatment regimens and a typical day of treatment were also included in the second version of the interview guide.

Qualitative coding and analysis

Audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim and coded for qualitative content analysis using ATLAS.ti version 8.0 (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; Berlin, Germany). The goal of the coding process was to identify and organize relevant concepts and expressions of study participants related to the preliminary conceptual model and interview guide. Through the review of each verbatim transcript, specific codes were developed from the participants’ words, with conceptually equivalent codes grouped to represent distinct concepts within broad domains of RRMM experience (i.e., symptoms, HRQOL impacts) and treatment experience (i.e., effectiveness, tolerability, mode of administration). The preliminary coding scheme was refined until team consensus was reached, and consistency of coding was assessed through repeated consultations among coders. A subset of three transcripts was coded independently by 2 researchers; after the initial coding, coders met and compared the concepts identified and codes assigned, resolving any differences until a consensus was obtained. The coding then proceeded following the agreed upon coding scheme, and coders met regularly to discuss emerging themes and codes. Saturation of treatment experience concepts was assessed in the CE data through a process that examined the appearance of novel concepts across interview transcripts and in accordance with the order in which interviews were conducted.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 23 patients with RRMM enrolled in the study; of these, 22 participants completed qualitative interviews (one patient was excluded because they were unfit to participate at the time of their scheduled interview). Interviews were conducted from November 11, 2019, to February 25, 2020. The mean interview participant age was 69 years, and the majority of participants were male (Table 1). On average, participants had received their initial MM diagnosis 5.6 years (range: 1.6–12.8 years) prior to study enrollment. The mean number of relapses was 2.3 (range: 1.0–6.0), and most participants had ≤ 3 relapses (n = 18, 81.8%); the mean time between the most recent clinician-defined relapse and study enrollment was 1.4 years (range: 0–3.8 years). On average, participants had 3.3 comorbidities (range: 1.0–7.0). Hypertension (n = 9, 40.9%), respiratory illnesses (n = 7, 31.8%), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (n = 6, 27.3%) were among the most common comorbidities.

Study participants had received a mean of 3.1 (range: 2.0–3.8) lines of therapy (Table 1). At enrollment, 59.1% of participants (n = 13) were using regimens containing dexamethasone, 36.4% (n = 8) daratumumab, 27.3% (n = 6) carfilzomib, and 18.2% (n = 4) lenalidomide; site staff reported all treatments included in the regimen, so treatments reported were not mutually exclusive. About one-third of patients used monotherapy (31.8%) or doublet therapy (31.8%) and 27.3% used triplet therapy. The mode of administration for participants’ current treatments varied: fewer participants were using oral therapy alone (n = 4, 18.2%) compared with intravenous or injectable treatment alone (n = 9, 40.9%) or both intravenous/injectable and oral treatment (n = 9, 40.9%).

Multiple myeloma experience

Example participant quotes regarding their MM experiences are shown in Table 2. Back pain (n = 9, 40.9%) and fatigue (n = 9, 40.9%) were the symptoms reported most frequently by participants; 27.3% of participants (n = 6) reported no symptoms (Table 3). Among the HRQOL impact concepts reported by participants (Table 4), physical function limitations (e.g., difficulty walking or standing) were most commonly reported (n = 19, 86.4%), followed by emotional impacts (e.g., worry/fear or sadness/depression) (n = 17, 77.3%), activity limitations related to MM (n = 16, 72.7%), and sleep disturbances (n = 14, 63.6%).

Treatment experience

Interview participants described their treatment experiences in three primary domains of interest: treatment effectiveness, treatment tolerability, and mode of administration (Table 5). Two effectiveness concepts were elicited during the interviews: symptom relief and clinical signs (Table 6). Ten RRMM participants (45.5%) reported that their treatment did not relieve their symptoms. Most participants (n = 15, 68.2%) perceived treatment effectiveness based on laboratory test results explained by their healthcare provider, and 40.9% (n = 9) based treatment effectiveness on symptom relief. Participants looked forward to receiving feedback about their laboratory results and not receiving it caused worry and concern. Without feedback, they were unable to tell whether the treatment was working or not and could not comment on the effectiveness of treatment with regards to clinical signs.

A total of 18 treatment tolerability concepts were elicited during the interviews. Most participants described experiencing gastrointestinal adverse events (n = 13, 59.1%) and fatigue (n = 13, 59.1%). The next most commonly reported concepts were sleep disturbances (n = 7, 31.8%) and allergic reactions (n = 7, 31.8%). Eight participants (36.4%) reported no adverse events.

Regarding mode of administration concepts, participants most commonly reported the overall duration of a typical treatment day (n = 15, 68.2%), treatment interfering with daily activities (n = 12, 54.5%), and duration of infusion (n = 11, 50.0%) as key elements of treatment burden (Table 6). According to participants, receiving RRMM treatment involves scheduling activities around days of treatment, not taking trips, not feeling well enough to spend time with family members, and depending on others to rearrange their schedule to provide transportation for clinic visits. Several interview participants reported traveling up to 2 h to receive their infusion. Factors that make a typical treatment day longer included laboratory tests and analyses; the treatment itself, which can vary in length; and the addition of other treatments (e.g., blood transfusion). Participants reported being satisfied with more simplified days of treatments. Descriptions provided by participants suggested that long infusions are inconvenient, tiresome, and emotionally draining (Table 6). In contrast, participants reported being satisfied with shorter infusions. Compared to infusions, participants preferred the rapid administration of injections. For oral treatment, the most frequently reported concepts were quantity of pills (n = 5, 22.7%) and convenience (n = 4, 18.2%). Participants mentioned the physical and mental ease and time savings (e.g., less travel time) of taking pills as part of the convenience of oral treatment.

Discussion

This qualitative study uncovered treatment experience-related concepts that study participants with RRMM reported as important. A central theme that resulted from this analysis was the burden of time dedicated to following the prescribed treatment regimen, with participant-perceived unfavorable factors including the duration of the typical day of treatment and the duration of infusions and injections of existing treatment. Participants indicated that they often plan their lives around treatment days due to the duration of infusion treatment and prolonged impacts of treatment-related adverse events that can occur. Many participants expressed experiencing gastrointestinal issues or fatigue and the need to plan their activities around when these adverse events have resolved and they have more energy.

Participants’ perceptions of treatment effectiveness depended largely on symptom relief and clinical signs. While many participants utilized symptom relief to indicate the effectiveness of the treatment, some had difficulty relying solely on this as they continued to experience symptoms following treatment and others were asymptomatic. Therefore, it is particularly important that healthcare providers share the results of the clinical tests with their patients, as many participants reported using this information to determine whether the treatment is working.

Participants in the first wave of interviews emphasized the burden of RRMM treatment, so we adjusted the interview guide for later waves to focus more on patient-reported treatment-related experiences than symptom-related concepts. However, the symptoms and impacts reported by study participants were consistent with the symptoms and impacts of RRMM reported in the literature. The adverse events endorsed by participants in this study were similar to those reported by participants with RRMM in the study conducted by Parsons et al. (e.g., fatigue, pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, sleep disturbances, mood swings) [18].

Our results were consistent with previous patient preference studies among patients with RRMM, in which drug administration (i.e., therapy mode of administration, number and duration of physician visits) has been identified as the most important factor in patients’ treatment decision-making [19, 20]. Mode of administration and the amount of time spent receiving therapy have also been identified as being associated with RRMM patients’ perceptions of treatment convenience [14]. In previous studies, some patients with RRMM have prioritized, preferred, and/or had higher satisfaction with oral treatments and in some cases have observed a willingness to accept a less effective therapy in exchange for more convenient treatments or treatments with less impact on quality of life (typically oral treatments) [19,20,21]. Compared with oral therapies, injectable therapies have been associated with increased time burden and higher indirect costs in patients with RRMM [14]. In the COLUMBA clinical trial, patients with RRMM reported greater treatment satisfaction with subcutaneous daratumumab therapy compared with intravenous infusion of daratumumab, and higher satisfaction with subcutaneous daratumumab therapy was maintained over 10 treatment cycles [22]. Previous research has shown that prolonged duration of therapy is associated with better outcomes in patients with RRMM and identified the need to remove barriers to the extended duration of treatment (i.e., until progression), such as improving treatment convenience [23]. Ensuring that RRMM treatment regimens are effective, tolerable, and convenient enough for patients may improve real-world adherence and enable patients to derive the full clinical benefits of treatment [16].

Previous qualitative studies have assessed the symptom burden of MM [24], so in light of participant responses, we shifted our focus in later interviews to treatment-related experiences rather than disease symptoms, as explained above. The treatment burden associated with the mode of administration for RRMM therapies is not typically examined in clinical trials, which focus more on safety and efficacy rather than other parts of the treatment experience that are important to patients (e.g., time, scheduling) [16]. Previous research has reported that the potential for treatment-free intervals is relevant to treatment decision-making for patients with MM as well as healthcare providers, suggesting that the burden of treatment plays a role in these treatment decisions and highlighting the need to gather evidence on patients’ treatment experiences [25]. Our qualitative interview results help fill the evidence gap for treatment experience–related data to further understand the patient experience as it relates to treatment burden in order to better inform treatment decision-making.

We acknowledge some limitations of our study. As is common among qualitative interview-based studies, the information reported here was drawn from a relatively small sample of participants (N = 22). Although evidence of concept saturation was observed in the qualitative dataset, suggesting the robustness of the qualitative analysis, caution should be taken when interpreting results due to the small sample size. The study protocol was amended partway through data collection and broadened the number of lines of prior therapy from up to 3 lines to up to 6 lines. The study population may be skewed toward patients with fewer relapses (68.2% of our study sample had ≤ 2 relapses); only four participants (18.2%) had ≥ 4 relapses, so we may have under-sampled patients with more substantial relapse experience. However, by opening eligibility to patients with more prior lines of therapy, the study may have expanded to include patients with more severe conditions and a longer duration of living with myeloma and therefore a different perspective. These patients may have come to terms with the severity of their condition and therefore minimized their symptom experience or treatment burden. In addition, our study population was composed only of white and Black/African American participants and as such may miss the experiences of patients from other ethnicities or racial groups. Although the absolute number of Black or African American participants in our study sample was small (n = 4), the proportion was higher than the general population (18.2% vs 13.4%) [26] and more closely approximates the ~ 20% MM case distribution observed in Black patients in the USA [27], as MM disproportionately affects Black patients [28]. Selection bias is possible due to the in-person interview design and outpatient sample. The study inclusion criteria focused on less severe cases, so the population was skewed towards less heavily treated patients (i.e., those with fewer relapses) who tend to be ambulatory (i.e., not hospitalized) with better functional status and more able to participate in the onsite in-person interviews conducted in this study. Finally, although we deliberately framed questions about symptoms in a way that separated symptoms experienced prior to RRMM diagnosis and symptoms experienced once treatment was initiated, it may have been difficult for participants to distinguish disease- or relapse-related symptoms from treatment-related symptoms. We cannot determine with certainty whether the patient-reported symptoms were in fact treatment-related, given a lack of physician corroboration, so the results reported herein represent a patient perspective on treatment-related symptoms.

Conclusions

The data collected from this study provide valuable insight into treatment experience concepts that are relevant to patients with RRMM. The results can be used to improve our understanding of the symptoms, HRQOL impacts, and treatment burden themes that are most important to patients. Specifically, these findings suggest that factors related to treatment administration time are important to patients and should be considered in patient-provider communications in clinical contexts. The results can also be used to inform future research into treatment preferences among patients with RRMM.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A (2021) Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin 71(1):7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21654

National Cancer Institute. SEER cancer stat facts: myeloma. 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html. Accessed April 12 2021

Kumar SK, Rajkumar V, Kyle RA et al (2017) Multiple myeloma Nat Rev Dis Primers 3(1):17046. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.46

Cowan AJ, Allen C, Barac A et al (2018) Global burden of multiple myeloma: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. JAMA Oncol 4(9):1221–1227. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2128

Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV et al (2004) Incidence of multiple myeloma in Olmsted County. Minnesota Cancer 101(11):2667–2674. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20652

Zhou L, Yu Q, Wei G et al (2021) Measuring the global, regional, and national burden of multiple myeloma from 1990 to 2019. BMC Cancer 21(1):606. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08280-y

Yamamoto L, Amodio N, Gulla A, Anderson KC (2021) Harnessing the immune system against multiple myeloma: challenges and opportunities. Front Oncol 10:606368. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.606368

Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ et al (2014) Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma: changes in early mortality and outcomes in older patients. Leukemia 28(5):1122–1128. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2013.313

Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A et al (2008) Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood 111(5):2516–2520. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129

Minnie SA, Hill GR (2020) Immunotherapy of multiple myeloma. J Clin Invest 130(4):1565–1575. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI129205

Dimopoulos MA, San-Miguel JF, Anderson KC (2011) Emerging therapies for the treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Eur J Haematol 86(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01542.x

Cornell RF, Kassim AA (2016) Evolving paradigms in the treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: increased options and increased complexity. Bone Marrow Transplant 51(4):479–491. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2015.307

MacEwan JP, Majer I, Chou JW, Panjabi S (2021) The value of survival gains from therapeutic innovations for US patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Ther Adv Hematol 12:20406207211027463. https://doi.org/10.1177/20406207211027463

Chari A, Romanus D, DasMahapatra P et al (2019) Patient-reported factors in treatment satisfaction in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Oncologist 24(11):1479–1487. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0724

Mikhael J, Ismaila N, Cheung MC et al (2019) Treatment of multiple myeloma: ASCO and CCO Joint Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol 37(14):1228–1263. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.18.02096

Terpos E, Mikhael J, Hajek R et al (2021) Management of patients with multiple myeloma beyond the clinical-trial setting: understanding the balance between efficacy, safety and tolerability, and quality of life. Blood Cancer J 11(2):40. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-021-00432-4

Maes H, Delforge M (2015) Optimizing quality of life in multiple myeloma patients: current options, challenges and recommendations. Expert Rev Hematol 8(3):355–366. https://doi.org/10.1586/17474086.2015.1021772

Parsons JA, Greenspan NR, Baker NA et al (2019) Treatment preferences of patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a qualitative study. BMC Cancer 19(1):264. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5467-x

Bauer S, Mueller S, Ratsch B et al (2017) Patient preferences regarding treatment options for relapsed refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Value Health 20(9):A451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.299

Wilke T, Mueller S, Bauer S et al (2018) Treatment of relapsed refractory multiple myeloma: which new PI-based combination treatments do patients prefer? Patient Prefer Adherence 12:2387–2396. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.S183187

Kerr C, Stubbs K, Trevor N et al (2019) PF717 Quality of life (QOL), perspectives on treatment and important outcomes for multiple myeloma (MM) patients and their carers: a mixed methods evidence synthesis. Hemasphere 3(S1):313–314

Usmani SZ, Mateos M-V, Hungria V et al (2021) Greater treatment satisfaction in patients receiving daratumumab subcutaneous vs. intravenous for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: COLUMBA clinical trial results. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 147(2):619–631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-020-03365-w

Hari P, Romanus D, Palumbo A et al (2018) Prolonged duration of therapy is associated with improved survival in patients treated for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma in routine clinical care in the United States. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 18(2):152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2017.12.012

Mortensen GL, Salomo M (2016) Quality of life in patients with multiple myeloma: a qualitative study. J Cancer Sci Ther 8(12):289–293

Mühlbacher AC, Nübling M (2011) Analysis of physicians’ perspectives versus patients’ preferences: direct assessment and discrete choice experiments in the therapy of multiple myeloma. Eur J Health Econ 12(3):193–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-010-0218-6

United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RHI225219 Accessed April 30 2021

Rosenberg PS, Barker KA, Anderson WF (2015) Future distribution of multiple myeloma in the United States by sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Blood 125(2):410–412. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-10-609461

Marinac CR, Ghobrial IM, Birmann BM, Soiffer J, Rebbeck TR (2020) Dissecting racial disparities in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J 10(2):19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020-0284-7

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Catherine Mirvis of OPEN Health (Bethesda, MD) and funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception, design, or interpretation of findings. Data collection and analysis were performed by FGS, RS, and KM. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript or critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by Advarra IRB (Columbia, MD). The study was conducted in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

NN has no conflicts of interest to disclose. JB and DC were employees of Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc. (TDCA), Lexington, MA, USA, at the time this research was conducted. PH has received honoraria for consulting from Takeda, BMS, Amgen, Karyopharm, Janssen, and Sanofi. FGS, RS, and KM were employees of Pharmerit – an OPEN Health Company, at the time the research was conducted.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nathwani, N., Bell, J., Cherepanov, D. et al. Patient perspectives on symptoms, health-related quality of life, and treatment experience associated with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Support Care Cancer 30, 5859–5869 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-06979-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-06979-7