Abstract

Purpose

Financial toxicity can have a major impact on the quality of life of cancer survivors but lacks conceptual clarity and understanding of the interrelationships of the various aspects that constitute financial toxicity. This study aims to extract major drivers and mediators along the pathway from cancer-related costs to subjective financial distress from the patients’ experiences to establish a better understanding of financial toxicity as a patient-reported outcome.

Methods

Qualitative semistructured interviews with 39 cancer patients were conducted in Germany and addressed patient experiences with cancer-related financial burden and distress in a country with a statutory health care system. Transcripts were analyzed using content analysis.

Results

Several aspects of financial burden need to be considered to understand financial toxicity. The assessment of the ability to make ends meet now or in the future and the subjective evaluation of financial adjustments—namely, the burden of applied financial adjustments and the availability of financial adjustment options—mediate the connection between higher costs and subjective financial distress. Moreover, bureaucracy can influence financial distress through a feeling of helplessness during interactions with authorities because of high effort, non-traceable decisions, or one’s own lack of knowledge.

Conclusion

We identified four factors that mediate the impact of higher costs on financial distress that should be addressed in further studies and targeted by changes in policies and support measures. Financial toxicity is more complex than previously thought and should be conceptualized and understood more comprehensively in measurements, including the subjective assessment of available adjustment options and perceived burden of financial adjustments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The costs due to a cancer diagnosis can have a major impact on treatment and patient outcomes. Over the last decade, the financial consequences of cancer diagnosis and their adverse long-term effects have received increasing attention, often referred to as financial toxicity (FT) [1]. Carrera et al. showed that cancer patients respond to higher medical costs and income loss with changes in consumption, which can have an impact on distress, indebtedness, and non-compliance with medical treatment, thereby influencing quality of life and health [1]. An association between financial distress and depression and anxiety is evident up to 10 years after diagnosis [2].

Even though a unified understanding and measurement of FT is lacking [3], there is consensus on the clear distinction between objective financial burden attributable to cancer and related subjective financial distress [1, 4, 5]. Objective financial burden is often measured as the increase in individual costs. Measurement of subjective financial distress often includes material, psychosocial, and behavioural aspects [6]. To date, our understanding of FT is mainly based on quantitative studies analyzing the prevalence of or risk factors for any measure (objective or subjective) or the associations between measures and patient outcomes. The present work defines FT as the mechanism by which the objective burden of higher costs becomes subjective financial distress. To develop interventions to reduce patients’ subjective financial distress and improve their quality of life, a better understanding of the relationship between higher costs and financial distress is needed [7]. Initial studies show that out-of-pocket costs and lost income are associated with financial distress [8,9,10]. However, this does not fully describe the context, as individuals in the same objective financial situation may perceive different levels of subjective financial distress.

It is likely that subjective financial distress does not derive directly from the existence and extent of higher costs [11]. First, risk factors for objective or subjective measures are not the same [12]. Second, there is only a low level of consistency and no significant association between patients’ objective and subjective financial burdens [13, 14].

To date, little is known about how objective financial burden becomes subjective financial distress. Carrera et al. point out that changes in consumption and other, potentially maladaptive, coping mechanisms frame this association [1]. Some studies suggest that making financial adjustments, e.g. delaying or avoiding care, applying for financial assistance, using savings, or reducing spending, is associated with financial distress [15, 16]. Factors such as having a mortgage/personal loan, poor workability, changes to employment, higher household bills, having dependents, or financial distress before diagnosis have been shown to be associated with subjective financial distress after diagnosis [8, 17] and have thus been put forth as possible explanatory factors of the association between higher costs and financial distress. However, these findings were often based on cross-sectional data, and causal mechanisms of FT remain mainly unclear [18].

Qualitative studies that analyze patients’ experiences of cancer-related costs and their subjective perceptions of financial distress and its emergence can shed light on relevant mediators and help to gain greater conceptual clarity of FT [19]. Generally, financial consequences from cancer are more pronounced in countries with high out-of-pocket costs for health care. The German health care system is a multipayer health care system with a combination of compulsory statutory (approximately 90% of the population) and private insurance. Most health care costs are covered by statutory health insurance with only low out-of-pocket costs that are capped at 2% (1% for chronically ill persons) of the gross annual household income upon request. During sickness, income loss is typically mitigated by sickness benefits, which cover approximately 70% of an individual’s regularly relevant total gross income for up to 78 weeks upon application. Subsequently, benefits covered by the social security system can be claimed, such as unemployment benefits or reduced earning capacity pensions. Therefore, studies in countries with universal health care and overall lower financial impact of diseases can help to better explain the emergence of subjective financial distress in cancer patients. Therefore, we aim to analyze major drivers and mediators along the pathway from cancer-related objective financial burden to subjective financial distress to establish missing links in the construct of FT from the patients’ experiences.

Methods

We chose a qualitative design with cancer survivors to capture potential mediators of the relationship between objective financial burden and subjective financial distress.

Recruitment of participants

Between May 2017 and April 2018, we gradually recruited participants, conducted interviews, and analyzed data. We reached potential participants in diverse ways, mainly through contacts at hospitals and resident specialists and through flyers. In total, 58 participants consented to taking part in an interview on the financial consequences of their cancer diagnoses. Initially, the inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (i) a diagnosis of a first breast, prostate, lung, or colorectal cancer; (ii) > 30 years of age; and (iii) completion of acute treatment for cancer within the last 5 years. At the beginning of the sampling process, we included every suitable patient. During purposive sampling, maximal variation was considered in terms of age, gender, socioeconomic status, family status, extent of financial impact, and financial distress, and of the 58 patients recruited, only 39 were interviewed with the potential to expand the developed theory until sampling saturation was reached. For the purposes of contrasting and reaching saturation, we had to broaden the inclusion criteria and included some patients within the 39 with other tumour entities, cancer recurrence, a second diagnosis of cancer, or patients who were in long-term therapy. Eligible participants were informed about the study, and in-depth semistructured interviews were conducted after patients provided written informed consent.

Conduction of the interviews

A semistructured interview guideline was used, including main questions related to changes in financial situation, consequences of financial changes for participants’ lives, and handling of financial changes. Depending on each participant’s choice, the interviews took place at the scientific institute, at the participant’s home, or during aftercare appointments. Two female research associates (SLL, an economist, and NS, a sociologist) with years of experience in qualitative health research conducted the interviews face to face. Field notes were recorded after each interview. The interviews normally included only the participant and one interviewer, but in seven interviews, family members were present at the request of the participant. The interviews lasted between 23 and 160 min, with a mean length of 68 min. All but one interview was audio-recorded with the interviewees’ permission.

Analysis

The transcripts of the interview records were analyzed using pseudonyms according to qualitative content analysis [20]. All interviews were conducted and analyzed in the German language. For the quotations and interview guide presented in this manuscript, we conducted a double-blind translation from German to English. Initially, six interviews were double-coded “data-driven” by trained coders from the qualitative working group at the scientific institute and were used to develop an initial code structure with categories. Subsequently, four interviews were double-coded by SLL and NS to enhance the coding tree. Either SLL or NS coded the remaining transcripts, and the respective other researcher checked the coding; discrepancies were discussed. The patients were categorized as having a high objective financial burden if the reported total costs, considering all financial changes, exceeded 10% of the net household equivalent income in the short term, or 5% in the long term (for at least 2 years). The remaining patients were categorized as having a low objective financial burden. Patients’ subjective financial distress was categorized as high or low by SLL and NS based on subjective expressions, and categorizations were discussed afterwards to reach a consensus. The classification was based on two independent assessments of the interview, but exemplary quotes that helped in the decision-making can be found in Fig. 1. We compared and contrasted the patients’ experiences related to the objective financial situation and subjective financial distress. MAXQDA 12.0 software was used to facilitate coding and comparison of the groups.

Results

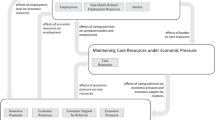

The patients’ characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Three out of 18 patients with low objective financial burden experienced subjective financial distress, and of those with high objective financial burden, approximately half experienced subjective financial distress. Comparing 12 financially distressed and 22 low-stress cancer patients (the remaining 5 patients could not be clearly assigned to either group), we derived four main distressing factors that patients can feel exposed to and that may cause subjective financial distress (see Fig. 2). These factors are related to the evaluation of financial adjustment options, the burden related to applied adjustments, the perceived ability to make ends meet, and bureaucracy; these factors are described in more detail below, and illustrative quotes showing exemplary contents can be found in Table 2. These factors are embedded in the context of the disease and cancer-related higher costs that interact with disease-related changes in needs and priorities, e.g. ascribing less value to consumption compared to health or more value to treating oneself.

Evaluation of financial adjustment options

Patients evaluated financial adjustments with regard to their availability. Financial distress arose from insufficient adaptive options, i.e. when patients felt they could not reduce expenditures or saw no way to increase resources through, in particular:

-

i.

money or financial help from third parties, including being rejected when asking for help or being met with a lack of understanding regarding financial problems;

-

ii.

earning extra money, which was not possible due to the regional labour market situations or their own physical constitutions;

-

iii.

not having savings to fall back on.

The perceived burden through the evaluation of options to adjust the financial situation through reducing expenditures or increasing resources was influenced by the extent of current non-reducible costs, existence of savings, quality of the social network, and job opportunities. High costs that influenced the emergence of financial distress included paying loan instalments, needing a car, and having dependents. Feeling ashamed of one’s financial situation can result in not asking relatives, friends, or authorities for help, and this can influence the evaluation of financial adjustment options. Having savings, few obligations, a social and accommodating employer, and the offer of altruistic help from others improved the evaluation of available adjustment options and reduced the emergence of distress. Contact with authorities could also help with determining available financial adjustments.

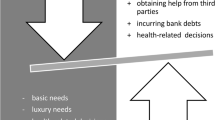

Burden of applied financial adjustments

Financial adjustments were evaluated with regard to the associated burden due to their implementation. Financial distress occurred when patients had to accept necessary expenditure cutbacks that made them feel they could no longer afford anything or when they tried to increase their resources by:

-

i.

consuming savings or incurring bank debts that changed their expected future financial situation,

-

ii.

getting help from third parties, which made them feel dependent, ashamed for needing help, or stressed while asking for or considering help, especially when being held responsible for their financial situations.

The perceived burden when reducing expenditures was influenced by the assessment of the necessities of consumption against the backdrop of one’s own needs. The main question was how easy is it for someone to spend less money?

Perceived ability to make ends meet

The assessment of the ability to make ends meet now and/or in the future is influenced by the increased costs and the evaluation of the aforementioned available and applied financial adjustments. Perceived financial distress in the current situation arose from the feeling of constantly having to deal with the financial situation caused by income decline, higher direct medical costs, waiting times on cash disbursements, the unpredictability of the timing of payments, and the exclusion of remedies/aids for refund. Anticipated financial distress in the future arose from worrying about the ability to deal with future unexpected events and costs or fearing old-age poverty. Overall, the evaluation of the ability to make ends meet and the financial adjustments influenced each other, e.g. the feeling of being forced to make burdensome financial adjustments to make ends meet, or fearing the inability to make ends meet in the future because of consuming savings now.

The perceived burden in evaluating one’s ability to make ends meet was influenced by financial education, financial behaviour, and perceived ability to get by with little money. Money management became challenging, especially as falling ill came unexpectedly and the related financial decline was unpredictable. An already strained financial situation at the time of the cancer diagnosis exacerbated the perceived inability to make ends meet.

Bureaucracy—effort, traceability, and knowledge

Patients could feel helpless in dealing with bureaucracy. Bureaucracy affected the patients and their experience of financial distress when they felt helpless in dealing with authorities and agencies, including banks and (statutory) insurance agencies. The perceived financial distress of bureaucracy occurred due to the following:

-

i.

time-consuming and complex processes when dealing with bureaucracy,

-

ii.

incomprehensible decisions by authorities,

-

iii.

confrontation with one’s own lack of knowledge about rules and regulations when dealing with authorities.

Financial distress arose when patients felt overwhelmed with applications and perceived their abilities to defend themselves as limited. They felt abandoned by the authorities because of a lack of satisfactory counselling on costs and claims or because of the great effort needed to contact counselling, even though they went to the cancer counselling services for help in dealing with bureaucracy or their financial situations.

The perceived burden of experiences with bureaucracy was influenced by knowledge and mental capabilities to handle information and paperwork. In addition, good experiences with social security institutions, prompt approvals, timely authorizations, help with inquiries about one’s own rights and unsolved questions, and sufficient information about one’s rights mitigated the feeling of helplessness in dealing with bureaucracy.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study establishing missing links in the construct of FT by analyzing patients’ subjective experiences along the pathway from cancer-related costs to subjective financial distress. We found that subjective financial distress arises from the interplay of multiple distress-causing factors, particularly:

-

a)

a lack of options to adapt financially;

-

b)

feeling burdened by the financial adjustments that have to be made, such as reducing spending and consumption, borrowing money, or using savings;

-

c)

a perceived inability to make ends meet now and/or in the future; and

-

d)

effortful contact with authorities and being confronted with non-traceable decisions and one’s own lack of knowledge.

Generally, our findings are in line with previous findings suggesting that several aspects of financial burden need to be taken into account to understand FT [6]. Other recent studies also highlight the importance of taking into account the perceived ability to make ends meet and the burden related to the application of financial adjustments when measuring financial distress [1, 5, 6, 21,22,23,24].

Additionally, we show that the subjective assessment of financial adjustments is a key factor for the emergence of subjective financial distress and is more important than the existence and extent of higher costs or applied financial adjustments. Special emphasis is placed on the individually perceived burden of applied financial adjustments and the evaluation of the availability of financial adjustment options. This can also explain contradictory findings with respect to help from third persons—money and support from family and friends or having a partner can help deal with the costs and mitigate distress [8, 25], or it can increase financial distress [23, 26]. We propose that this depends on the evaluation of the burden of accepting help from others.

To date, the assessment of the availability of financial adjustment options has not been considered in the literature. Nevertheless, having savings, employment opportunities, and high fixed expenses are significant drivers of financial distress [8, 21, 22, 27, 28]. These factors could be interpreted as reflecting the availability of options to adjust to the financial situation. Carrera et al. proposed that the application of potential maladaptive financial adjustments is the link between objective costs and financial distress [1]. We illustrate that the patient’s subjective evaluation of available options and burden of applied financial adjustments determines whether financial adjustments become maladaptive or are experienced as relieving, which is an important missing link in the construct of FT.

We assume that having savings at diagnosis strongly influences assessment of the financial situation. This is also reflected in the fact that increased FT is associated with having savings covering less than one month, even after adjusting for income [29]. Savings and household net worth are associated with higher financial literacy [30]. Financial literacy empowers people to manage their finances, which could be related to a strong competence in identifying different options for financial adjustments, not perceiving them as a burden, a greater knowledge of rules and regulations, and the confidence to find solutions to make ends meet; together, these are the factors that influence the emergence of financial distress. This implies that higher financial literacy might be helpful to empower patients in dealing with the financial burden of their illness [30, 31]. One study showed that cancer patients rated a financial literacy course as helpful in navigating the cost of cancer care, and the most important content they wanted to be included in the course was employment issues, barriers to talking about costs, and resources for financial support [21].

Bureaucracy is an additional missing link in the construct of FT. Difficult contact with authorities, a lack of knowledge about procedures, and incomprehensible decisions mediate the relationship between objective costs and financial distress. This has thus far rarely been addressed in studies, although as a partial aspect of bureaucracy, transparency of expected costs has been identified as a key component of financial distress, and knowledge of what to expect was therefore put forth as an important factor to reduce distress [10, 21, 28]. Patient counselling and assistance programmes have been found to mitigate financial distress [21]. Consulting services can help patients cope with difficult bureaucracy processes. In the authors’ view, however, it would be equally advisable, in addition to expanding counselling services, to make an effort to simplify and automate procedures and requests for (cancer) patients so that applications are less time-consuming, decisions about benefits are more transparent and comprehensible, and regulations are generally less complex and easier to understand, so that patients are not overwhelmed when dealing with authorities and bureaucracy.

Existing instruments measuring subjective financial distress often include only the evaluation of the psychosocial responses in a single question on financial difficulties, or they ask about the existence of passive financial resources, support-seeking, changes in financial spending, or coping with care or with ones’ lifestyle [6]. Based on our results, we recommend that the patients’ circumstances and subjective evaluation of the situation be considered in future questionnaires. Items should not be too specific and cover the patients’ individual assessment of financial adjustments, including burden and availability, current and future perspective on the ability to make ends meet, and experiences with bureaucracy, which we found to be important missing links in the construct of FT.

Limitations

Although we conducted 39 interviews and reached saturation, the generalizability of the findings to all patients with cancer may be limited, e.g. to young cancer patients or families of children with cancer or patients from other countries or regions. Especially for long-term cancer survivors, other factors might be of relevance that lead to long-term financial distress. Due to the social security system with statutory health insurance in Germany, direct medical costs are lower than in other countries and probably less important for the emergence of financial stress. Nevertheless, the four identified main factors that mediate financial distress should be of international interest. It should be highlighted that this qualitative study is limited in scope, but further research should explore the validity of this model in quantitative studies with different samples and in other contexts.

Conclusion

In this study, we confirm that subjective financial distress can arise from higher costs and other distress-causing factors, such as maladaptive financial adjustments and an inability to make ends meet, indicating that measurement should be multifactorial. Nevertheless, we find that despite asking about the existence of financial adjustments in questionnaires, the subjective assessment of available options to adjust to the financial situation and perceived burden of the financial adjustments that have to be made is relevant for evaluating subjective financial distress. In addition, the burden of bureaucracy—due to effort, lack of traceability, or knowledge deficits—must be considered if subjective financial stress is to be analyzed comprehensively. In the overall context of FT, patients experiencing several of the four identified factors might feel that the financial side effects of cancer—higher costs, changed priorities and needs, or bureaucracy—dominate one’s life.

Availability of data and material

Participants of this study were guaranteed that only the study research team would have access to the interviews and transcripts; thus, data are not available for sharing.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Change history

23 February 2022

The original version of this paper was updated to add the missing compact agreement Open Access funding note.

References

Carrera PM, Kantarjian HM, Blinder VS (2018) The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 68(2):153–165. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21443

Götze H, Friedrich M, Taubenheim S et al (2020) Depression and anxiety in long-term survivors 5 and 10 years after cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 28(1):211–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04805-1

Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD et al (2017) Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst 109(2):djw205. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djw205

Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR (2016) Minimizing the “financial toxicity” associated with cancer care: advancing the research agenda. J Natl Cancer Inst 108(5):djv410. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv410

Yabroff KR, Bradley C, Shih Y-CT (2020) Understanding financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: strategies for prevention and mitigation. J Clin Oncol 38(4):292–301. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.01564

Witte J, Mehlis K, Surmann B et al (2019) Methods for measuring financial toxicity after cancer diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review and its implications. Ann Oncol 30(7):1061–1070. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz140

Printz C (2015) Cancer survivors face steep economic burdens: excessive medical expenses and loss of productivity at work plague some, even years after initial diagnosis. Cancer 121(20):3561–3562. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29004

Mols F, Tomalin B, Pearce A et al (2020) Financial toxicity and employment status in cancer survivors. A systematic literature review. Support Care Cancer 28(12):5693–5708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05719-z

Politi MC, Yen RW, Elwyn G et al (2021) Women who are young, non-white, and with lower socioeconomic status report higher financial toxicity up to 1 year after breast cancer surgery: a mixed-effects regression analysis. Oncologist 26(1):e142–e152. https://doi.org/10.1002/onco.13544

Offodile AC, Asaad M, Boukovalas S et al (2021) Financial toxicity following surgical treatment for breast cancer: a cross-sectional pilot study. Ann Surg Oncol 28:2451–2462. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09216-9

Azzani M, Roslani AC, Su TT (2015) The perceived cancer-related financial hardship among patients and their families: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 23(3):889–898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2474-y

Pisu M, Azuero A, Benz R et al (2017) Out-of-pocket costs and burden among rural breast cancer survivors. Cancer Med 6(3):572–581. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1017

Khera N, Chang Y, Hashmi S et al (2014) Financial burden in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 20(9):1375–1381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.05.011

Chen JE, Lou VW, Jian H et al (2018) Objective and subjective financial burden and its associations with health-related quality of life among lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 26(4):1265–1272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3949-4

Mady LJ, Lyu L, Owoc MS et al (2019) Understanding financial toxicity in head and neck cancer survivors. Oral Oncol 95:187–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.06.023

Bouberhan S, Shea M, Kennedy A et al (2019) Financial toxicity in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol 154(1):8–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.04.003

Sharp L, Timmons A (2016) Pre-diagnosis employment status and financial circumstances predict cancer-related financial stress and strain among breast and prostate cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 24(2):699–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2832-4

Gordon LG, Merollini KMD, Lowe A et al (2017) A systematic review of financial toxicity among cancer survivors. Patient 10(3):295–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-016-0204-x

Park J, Look KA (2018) Relationship between objective financial burden and the health-related quality of life and mental health of patients with cancer. Journal of oncology practice 14(2):e113–e121. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2017.027136

Schreier M (2012) Qualitative content analysis in practice, 1st edn. Sage, Los Angeles

Shankaran V, Linden H, Steelquist J et al (2017) Development of a financial literacy course for patients with newly diagnosed cancer. Am J Manag Care 23(3 Suppl):S58–S64

Fitch M, Longo CJ (2018) Exploring the impact of out-of-pocket costs on the quality of life of Canadian cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol 36(5):582–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2018.1486937

Hanly P, Maguire R, Ceilleachair AO et al (2018) Financial hardship associated with colorectal cancer survivorship: the role of asset depletion and debt accumulation. Psychooncology 27(9):2165–2171. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4786

de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ et al (2014) The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer. Cancer 120(20):3245–3253. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28814

Fitch MI, Longo CJ, Chan RJ (2021) Cancer patients’ perspectives on financial burden in a universal healthcare system: analysis of qualitative data from participants from 20 provincial cancer centers in Canada. Patient Educ Couns 104(4):903–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.08.013

Longo CJ, Fitch MI, Banfield L et al (2020) Financial toxicity associated with a cancer diagnosis in publicly funded healthcare countries: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 28(10):4645–4665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05620-9

Pearce A, Tomalin B, Kaambwa B et al (2019) Financial toxicity is more than costs of care: the relationship between employment and financial toxicity in long-term cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 13(1):10–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0723-7

Blum-Barnett E, Madrid S, Burnett-Hartman A et al (2019) Financial burden and quality of life among early-onset colorectal cancer survivors: a qualitative analysis. Health Expect 22(5):1050–1057. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12919

Hazell SZ, Fu W, Hu C et al (2020) Financial toxicity in lung cancer: an assessment of magnitude, perception, and impact on quality of life. Ann Oncol 31(1):96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.006

Goyal K, Kumar S (2021) Financial literacy: a systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Int J Consum Stud 45(1):80–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12605

Longo CJ, Fitch M, Grignon M et al (2016) Understanding the full breadth of cancer-related patient costs in Ontario: a qualitative exploration. Support Care Cancer 24(11):4541–4548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3293-0

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in this study and who shared their experiences regarding this personal topic with us. For their topical discussions on and insights into the issue of financial toxicity, we thank Jürgen Walther and Marie Rösler from the German Cancer Society and Sven Weise from the Cancer Society of Saxony-Anhalt. For their assistance with recruiting patients for this study, we acknowledge scientific assistants Julia Faltus and Johannes Niebuhr and our cooperation partners within the outpatient departments and doctors’ practices. For helpful remarks on the manuscript, we thank Helen Mayrhofer.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the German Cancer Aid (grant number 70112452: Principal Investigator: Matthias Richter).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Patient interviews and data analysis were performed by Sara Lückmann and Nadine Schumann. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Sara Lückmann, and all authors commented on previous versions of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty at Martin Luther University, Halle-Wittenberg (2016–126).

Consent to participate

Interviews were conducted only after patients had given written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Participants provided written informed consent to have their pseudonymized data used for scientific analyses.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lueckmann, S.L., Schumann, N., Kowalski, C. et al. Identifying missing links in the conceptualization of financial toxicity: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 30, 2273–2282 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06643-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06643-6