Abstract

Purpose

Common residual symptoms among survivors of colorectal cancer (CRC) are sleep difficulties and gastrointestinal symptoms. Among patients with various gastrointestinal (inflammatory) diseases, sleep quality has been related to gastrointestinal symptoms. For CRC survivors, this relation is unclear; therefore, we examined the association between sleep quality and quantity with gastrointestinal symptoms among CRC survivors.

Methods

CRC survivors registered in the Netherlands Cancer Registry—Southern Region diagnosed between 2000 and 2009 received a survey on sleep quality and quantity (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) and gastrointestinal symptoms (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Quality of Life Questionnaire-Colorectal 38, EORTC QLQ-CR38) in 2014 (≥ 4 years after diagnosis). Secondary cross-sectional data analyses related sleep quality and quantity separately with gastrointestinal symptoms by means of logistic regression analyses.

Results

In total, 1233 CRC survivors were included, of which 15% reported poor sleep quality. The least often reported gastrointestinal symptom was pain in the buttocks (15.1%) and most often reported was bloating (29.2%). CRC survivors with poor sleep quality were more likely to report gastrointestinal symptoms (p’s < 0.01). Survivors who slept < 6 h were more likely to report symptoms of bloating or flatulence, whereas survivors who slept 6–7 h reported more problems with indigestion.

Conclusions

Worse sleep quality and short sleep duration were associated with higher occurrence of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Implications for cancer survivors

Understanding the interplay between sleep quality and gastrointestinal symptoms and underlying mechanisms adds to better aftercare and perhaps reduction of residual gastrointestinal symptoms in CRC survivors by improving sleep quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is worldwide one of the most common types of cancer [1]. Overall, incidence has been increasing and 5-year survival rates have been improving over the last two decades resulting in increasing numbers of CRC survivors [2]. CRC survivors are faced with the residual symptoms of both cancer and its treatment [3,4,5]. Two common residual symptoms among CRC survivors are sleep difficulties and gastrointestinal symptoms [3,4,5]. Both sleep difficulties and gastrointestinal symptoms have been associated with worse health outcomes (e.g., functioning and quality of life) in cancer survivors [3,4,5]. Sleep difficulties have been linked to heightened subjective perceptions of anxiety and pain among various cancer populations [5]. Moreover, gastrointestinal symptoms themselves can be a source of pain and physical discomfort, negatively affecting quality of life [3].

In patients with other gastrointestinal diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, and gastroesophageal reflux disease, sleep difficulties are related to gastrointestinal symptoms [6,7,8]. More specifically, poor sleep quality has been linked to exacerbations among patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease [6] and Crohn’s disease [7, 8]. Poor sleep quality involves poor subjective sleep quality, long sleep latency, short sleep duration, sleep inefficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction [9]. A short total sleep duration as a consequence of long sleep latency, waking after sleep onset or early waking, is common among cancer survivors [9, 10] and has shown to be associated with poor outcomes [11, 12].

Currently, it remains unknown whether there is an association between sleep quality/quantity and gastrointestinal problems in CRC survivors. The aim of this study was therefore to examine the association between sleep quality and quantity with gastrointestinal symptoms among CRC survivors. Gaining insight in the association between these common residual symptoms could optimize future treatment guidelines. Existing interventions for sleep problems may be more effectively applied, improving not only sleep quality and quantity, but also reducing the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms. In turn, reducing gastrointestinal symptoms may also improve sleep quality.

Methods

Participants

For this secondary data analyses, we used data from a longitudinal, population‐based cohort study including CRC survivors registered within the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR), which records data on all patients newly diagnosed with cancer [13]. Patients in the NCR—Southern Region, an area with 2.4 million inhabitants, were selected [14]. All patients diagnosed with stage I to IV CRC between 2000 and 2009 were eligible. Patients who had unverifiable addresses, had a cognitive impairment, died before the start of the study or were terminally ill, had stage 0 disease/carcinoma in situ, or were already included in another study (n = 169) minimizing patient burden and interference were excluded. A complete overview of the selection of patients can be found on our Web site under data and documentation (https://www.dataarchive.profilesregistry.nl/study_units/view/22). We used data from the fifth wave (questionnaires were sent between January 23, 2014, and May 21, 2014), as sleep quality and quantity were merely measured at this measurement occasion. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the medical ethics committee of the Maxima Medical Centre in Veldhoven, the Netherlands (approval number 0822). All participants signed informed consent.

Data collection

Data was collected via the Patient‐Reported Outcomes Following Initial Treatment and Long‐Term Evaluation of Survivorship (PROFILES) registry [15]. Survivors received a letter from their (former) attending specialist to inform them about the study. The letter included a link to a secure website, a login name, and a password so that interested patients could provide consent and complete questionnaires online. Those who preferred written communication could return a postcard, after which they received our paper and pencil informed consent form and questionnaire. Non-respondents were sent a reminder letter and a paper and pencil questionnaire within 2 months.

Measures

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

Survivors’ sociodemographic (sex and age) and clinical information (tumor type, cancer stage, primary treatment, and time since diagnosis) were extracted from the NCR [14]. Information on marital status was self-reported. Comorbidity was assessed using yes/no statements to whether survivors experienced one or more of 14 chronic conditions using the Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire [16].

Sleep quality and quantity

Sleep quality and quantity experienced in the previous month were measured using the 19-item self-reported Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [17]. The 19-items generate seven component scores: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration (i.e., quantity), habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. Each of these seven component scores is weighted equally on a scale ranging from 0 to 3, 0 indicating no difficulty and 3 indicating severe difficulty. Sleep quantity (i.e., sleep duration, “how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night?”) was reported and is scored into; > 7 h (0), 6–7 h (1), 5–6 h (2), and < 5 h (3) [17]. Overall, sleep quality (global PSQI score) was calculated by summing the seven component scores, which range from 0 to 21 [17]. Higher scores indicate worse sleep quality, and a global PSQI score > 8 is consistent with poor sleep quality among cancer populations [18].

Gastrointestinal symptoms

Gastrointestinal symptoms were assessed with the gastrointestinal tract symptom subscale of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Colorectal cancer 38 (EORTC QLQ-CR38) [19]. The 38-item EORTC QLQ-CR38 is applicable for patients who currently have or have survived CRC [19]. The subscale gastrointestinal tract symptoms consists of five items, which represent symptoms CRC survivors commonly suffer from having a bloated feeling in the abdomen, abdominal pain, pain in the buttocks, bothered by gas (flatulence), and belching. Each symptom was rated how often it appeared last week, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). For the current study, the gastrointestinal symptoms, “abdominal pain,” “pain in the buttocks,” “indigestions,” and “bloating,” were dichotomized into not at all (answer category 1) versus experiencing any symptoms (answer categories 2, 3, or 4). As “flatulence” is a common symptom among healthy populations, we dichotomized it into not at all or a little (answer categories 1 or 2) versus moderate or a lot (answer categories 3 or 4), to differentiate effectively among our sample of CRC survivors.

Statistical analyses

Differences between respondents and non-respondents on all categorical sociodemographic (sex, age at time of questionnaire) and clinical characteristics (tumor type, cancer stage, primary cancer treatment, and time since diagnosis) were compared by means of chi-square tests. Descriptives for all sociodemographic (sex, age at questionnaire, and marital status) and clinical characteristics (tumor type, cancer stage, primary treatment, time since diagnosis, and comorbidities) were run. Logistic regression analyses were performed relating sleep quality and sleep quantity separately (independent variables) to each gastrointestinal symptom (i.e., bloating, abdominal pain, pain in buttocks, flatulence, and indigestion; dependent variables), while controlling for sociodemographic and clinical variables given their known associations with the (in)dependent variables. Logistic regression analyses including the original scoring of sleep quantity (> 7; 6–7; 5–6; < 5) were impossible due to the low number of CRC survivors in the category < 5 h of sleep (n = 32). Therefore, this category was merged into < 6 h of sleep. Analyses were performed using SPSS, version 24, and a significance level of 0.05 was used.

Results

Patient characteristics

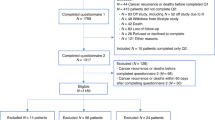

Of the 1547 eligible CRC survivors, 1233 (80%) responded and were included in our analyses (Fig. 1). No differences were seen between respondents and non-respondents on sociodemographic or clinical variables of interest (Table 1). Overall, 58.3% of CRC survivors were male (n = 719), the majority were older than 65 years (72.2%), and married or living together (76.6%). Nearly 60% were diagnosed with colon cancer (n = 727), and approximately one-third of survivors were diagnosed with a stage I CRC. Almost all survivors received surgery as a primary treatment (99.7%) (Table 1).

Sleep quality, quantity, and gastrointestinal problems characteristics

Fifteen percent (n = 181) of the CRC survivors reported poor global sleep quality. The majority reported > 7 h of sleep (73.1%, n = 869), whereas 18.3% (n = 217) reported 6–7 h, and 8.6% (n = 102) reported < 6 h of sleep. Regarding the gastrointestinal symptoms, 29.2% experienced bloating, 19.9% reported abdominal pain or pain in the buttocks (15.1%), nearly a quarter experienced flatulence (24.2%), and 25.7% reported symptoms of indigestion. CRC survivors who rated their sleep quality as poor or who reported a lower number of hours slept (quantity), reported more often gastrointestinal symptoms (i.e., bloating, abdominal pain, flatulence, and indigestion) (p’s < 0.01, Figs. 2 and 3).

Associations between sleep quality, quantity, and gastrointestinal symptoms

CRC survivors who reported a poor global sleep quality were more likely to report symptoms of bloating (adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 1.13; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.08–1.18), abdominal pain (OR = 1.15; 95%CI = 1.09–1.20), pain in the buttocks (OR = 1.06; 95%CI = 1.01–1.12), flatulence (OR = 1.10; 95%CI = 1.06–1.15), and indigestion (OR = 1.11; 95%CI = 1.05–1.16) (Table 2). CRC survivors who reported sleeping 6–7 h a night were more likely to report symptoms of indigestion (OR = 1.50; 95%CI = 1.06–2.12) compared to survivors reporting > 7 h of sleep. CRC survivors reporting < 6 h of sleep were more likely to report symptoms of bloating (OR = 1.74; 95%CI = 1.11–2.73) and flatulence (OR = 1.84; 95%CI = 1.16–2.93) compared to CRC survivors who report > 7 h of sleep.

Discussion

Our results showed that CRC survivors reporting poor sleep quality were more likely to report gastrointestinal symptoms: bloating, abdominal pain, pain in the buttocks, flatulence, and indigestion. Furthermore, sleep quantity (i.e., hours of sleep) was related to experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms; CRC survivors who slept less than 6 h reported more symptoms of bloating or flatulence, whereas CRC survivors who slept 6–7 h reported more problems with indigestion. The findings of our study are in line with previous research [7, 20,21,22,23]. A cross-sectional study among the general population (n = 3228) showed that those with poor sleep quality were more likely to experience gastrointestinal symptoms [20]. Another study including 2674 people undergoing a health-check report that those with (35.8%) impaired sleep quality reported more gastrointestinal symptoms compared to those without impaired sleep quality [21]. Results from a population-based study (n = 2269) showed that the prevalence of irritable bowel disease was higher among those who reported experiencing sleep disturbances [22]. Among patients with inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases, similar associations have been reported [7, 23]. A longitudinal study among patients whose Crohn’s disease was in remission (n = 1291) showed that those with impaired sleep had twofold increased risk of active disease 6 months later [7]. The majority of studies are cross-sectional in nature and assume that impaired sleep quality precedes gastrointestinal symptoms; however, causality remains unclear. It can also be hypothesized that experienced gastrointestinal symptoms cause impairments in sleep quality.

Associations between sleep quality and gastrointestinal symptoms may be linked through immune functioning. We know that alterations of cytokines like interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) are known manifestations in various gastrointestinal diseases, including CRC [24]. Moreover, these cytokines are major contributors to sleep difficulties [25], and gastrointestinal symptoms [24]. In turn, sleep difficulties such as sleep deprivation are known to up-regulate these inflammatory cytokines [25]. Thus, poorer sleep may lead to elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which in turn can contribute to the exacerbation of gastrointestinal symptoms.

This study has some limitations. The current sample consisted of CRC survivors 4 to 14 years after diagnosis; therefore, we introduced survivorship bias to our study. It has been indicated that poorer sleep quality is related to poorer overall survival; hence, those deceased CRC survivors may have had a poorer overall sleep quality [26]. Nevertheless, respondents versus non-respondents however showed no statistical differences on sociodemographic or clinical characteristics. Furthermore, we have no information on current disease status (e.g., recurrence or secondary cancers) nor whether survivors were on active treatment during questionnaire completion, while this could increase experienced gastrointestinal symptoms and sleep problems. Nonetheless, all included participants were diagnosed 4 years or longer ago, and the time since diagnosis was not related to experienced gastrointestinal symptoms nor sleep quality and quantity (data not shown). Furthermore, we examined time after diagnosis across tumor stages, to see whether stage IV CRC patients were more recently diagnosed and hence more likely to be receiving current treatment. Results showed that there was no relation between tumor stage and years after diagnosis indicating that our findings can be seen as robust. The cross-sectional design of these secondary data analyses prohibits us from making causal interferences. Although our analyses demonstrate a significant relation between sleep quality and quantity with gastrointestinal symptoms, the causality of the studied factors cannot be inferred. Hence, a bi-directional relationship between sleep quality/quantity and gastrointestinal problems remains plausible. CRC survivors may end up in a vicious circle of increased sleeping problems and gastrointestinal problems, especially as both are known to be driven by and resulting in increased inflammation [24, 25]. Nevertheless, knowledge on the possibly reciprocal relation between gastrointestinal symptoms and sleep quality is valuable for health-care providers and may result in awareness that besides asking about gastrointestinal symptoms, it is also important to ask for sleep problems in follow-up consultations. When patients mention one of both, it is important to explore the other component as both often co-occur. Furthermore, when trying to intervene on gastrointestinal symptoms, it may be valuable to also treat sleep problems or support patients to improve sleep quality and quantity as well, and vice versa.

Our study also poses several strengths, as this is the first study relating sleep quality and quantity to gastrointestinal symptoms among CRC survivors. Furthermore, our study has a high response rate (79.7%), has a large sample size (n = 1233), is representative of the total sample of CRC survivors given our population-based sampling method, and included sociodemographic and clinical characteristics as covariates.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study showed that worse sleep quality and short sleep duration are associated with a higher occurrence of gastrointestinal symptoms (i.e., bloating, abdominal pain, pain in the buttocks, flatulence, and indigestion) among CRC survivors ≥ 4 years after initial treatment. Our results highlight the relative importance of improving sleep and gastrointestinal symptoms among CRC survivorship when it comes to healthy cancer survivorship. Ultimately, understanding the interplay between sleep quality/quantity and gastrointestinal symptoms and underlying mechanisms might allow for better aftercare.

Data availability

Data is freely available upon request for non-commercial use via www.profilesregistry.nl

Code availability

Upon request

References

Parkin DM et al (2005) Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 55(2):74–108

Rawla P, Sunkara T, Barsouk A (2019) Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz Gastroenterol 14(2):89–103

Gatta G et al (2007) Late outcomes of colorectal cancer treatment: a FECS-EUROCARE study. J Cancer Surviv 1(4):247–254

Denlinger CS, Barsevick AM (2009) The challenges of colorectal cancer survivorship. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 7(8):883–93 (quiz 894)

Ancoli-Israel S, Moore PJ, Jones V (2001) The relationship between fatigue and sleep in cancer patients: a review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 10(4):245–255

Dickman R et al (2007) Relationships between sleep quality and pH monitoring findings in persons with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Sleep Med 3(5):505–513

Ananthakrishnan AN et al (2013) Sleep disturbance and risk of active disease in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 11(8):965–971

Sofia MA et al (2020) Poor sleep quality in Crohn’s disease is associated with disease activity and risk for hospitalization or surgery. Inflamm Bowel Dis 26(8):1251–1259

Chen D, Yin Z, Fang B (2018) Measurements and status of sleep quality in patients with cancers. Support Care Cancer 26(2):405–414

Rutherford C et al (2020) Patient-reported outcomes and experiences from the perspective of colorectal cancer survivors: meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. J Patient Rep Outcomes 4(1):27

Wu Y, Zhai L, Zhang D (2014) Sleep duration and obesity among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep Med 15(12):1456–1462

Cappuccio FP et al (2010) Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep 33(5):585–592

Mols F et al (2018) Symptoms of anxiety and depression among colorectal cancer survivors from the population-based, longitudinal PROFILES Registry: prevalence, predictors, and impact on quality of life. Cancer 124(12):2621–2628

Janssen-Heijnen MLG et al (2005) Results of 50 years cancer registry in the South of the Netherlands: 1955–2004 (in Dutch). Eindhoven Cancer Registry: Eindhoven

van de Poll-Franse LV et al (2011) The Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship registry: scope, rationale and design of an infrastructure for the study of physical and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivorship cohorts. Eur J Cancer 47(14):2188–2194

Sangha O et al (2003) The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum 49(2):156–163

Buysse DJ et al (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28(2):193–213

Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA (1998) Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Psychosom Res 45(1):5–13

Sprangers MA, te Velde A, Aaronson NK (1999) The construction and testing of the EORTC colorectal cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire module (QLQ-CR38). European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Study Group on Quality of Life. Eur J Cancer 35(2):238–47

Cremonini F et al (2009) Sleep disturbances are linked to both upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population. Neurogastroenterol Motil 21(2):128–135

Lei WY et al (2019) Sleep disturbance and its association with gastrointestinal symptoms/diseases and psychological comorbidity. Digestion 99(3):205–212

Vege SS et al (2004) Functional gastrointestinal disorders among people with sleep disturbances: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc 79(12):1501–1506

Iskandar HN et al (2020) Self-reported sleep disturbance in Crohn’s disease is not confirmed by objective sleep measures. Sci Rep 10(1):1980

Ali T et al (2013) Sleep, immunity and inflammation in gastrointestinal disorders. World J Gastroenterol 19(48):9231–9239

Ranjbaran Z et al (2007) The relevance of sleep abnormalities to chronic inflammatory conditions. Inflamm Res 56(2):51–57

Mormont MC et al (2000) Marked 24-h rest/activity rhythms are associated with better quality of life, better response, and longer survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer and good performance status. Clin Cancer Res 6(8):3038–3045

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; draft and/or revised the work critically; approved the final submitted version; and agree to be accountable for the submitted work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The primary study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the Maxima Medical Centre in Veldhoven, the Netherlands (approval number 0822).

Consent to participate and publication

All participants provided consent including data collection, analyses, storage, and publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schoormans, D., van Es, B., Mols, F. et al. The relation between sleep quality, sleep quantity, and gastrointestinal problems among colorectal cancer survivors: result from the PROFILES registry. Support Care Cancer 30, 1391–1398 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06531-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06531-z