Abstract

Purpose

To study the use of interventions and symptom relief for adult patients with incurable cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit providing integrated oncology and palliative care services.

Methods

All admissions during 1 year were assessed. The use of interventions was evaluated for all hospitalizations. Patients with assessments for worst and average pain intensity, tiredness, drowsiness, nausea, appetite, dyspnea, depression, anxiety, well-being, constipation, and sleep were evaluated for symptom development during hospitalization. Descriptive statistics was applied for the use of interventions and the paired sample t-test to compare symptom intensities (SIs).

Results

For 451 admissions, mean hospital length of stay was 7.0 days and mean patient age 69 years. More than one-third received systemic cancer therapy. Diagnostic imaging was performed in 66% of the hospitalizations, intravenous rehydration in 45%, 37% received antibiotics, and 39% were attended by the multidisciplinary team. At admission and at discharge, respectively, 55% and 44% received oral opioids and 27% and 45% subcutaneous opioids. For the majority, opioid dose was adjusted during hospitalization. Symptom registrations were available for 180 patients. Tiredness yielded the highest mean SI score (5.6, NRS 0–10) at admission and nausea the lowest (2.2). Significant reductions during hospitalization were reported for all assessed SIs (p ≤ 0.01). Patients receiving systemic cancer therapy reported symptom relief similar to those not on systemic cancer therapy.

Conclusion

Clinical practice and symptom relief during hospitalization were described. Symptom improvements were similar for oncological and palliative care patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer patients treated with palliative intent suffer from a diversity of symptoms [1,2,3]. The symptom burden remains high over time, both on a population level and throughout the disease trajectory [4,5,6,7]. Suboptimal symptom assessment and management are major contributors to inadequate symptom control [8]. The relevant and ongoing attention to effectiveness of healthcare services also warrants a focus on the interventions used to achieve symptom improvement [9,10,11].

Systematic symptom assessment is pivotal in palliative care and may improve survival [12, 13]. The patient perspective is an important element of cancer care, as the healthcare providers tend to underestimate the patient’s symptom burden [12, 14, 15]. Patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) is an umbrella term covering the patient’s perspective on physical and psychological well-being, including symptom severity, symptom impact, and treatment effects [12]. Assessment tools reporting PROMs are recommended and a multitude of symptom assessment tools exist [12, 16,17,18]. Although many studies report results based on systematic symptom assessment, publications on the use of interventions and overall symptom development during hospitalization in palliative care units are fewer and less comprehensive [19,20,21].

Integration of oncology and palliative care implies earlier referral to palliative care programs and palliative care units [12]. This approach may enhance symptom control and family satisfaction, improve survival, and represent a potential for better utilization of healthcare resources [12]. Acute palliative care units (APCUs) facilitating early integration of oncology and palliative care are endorsed by the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) [22,23,24]. Rapid symptom relief, increased quality of life, and beneficial use of interventions are essential goals for the APCU stay [12, 25]. However, the optimal content of palliative care integrated into oncology is not established [12].

A 1-year healthcare improvement study was conducted in an ESMO Designated Centre of Integrated Oncology and Palliative Care, aiming to answer the following research questions:

-

1.

Which interventions are used during hospitalization at the APCU?

-

2.

How does patient-reported symptom intensity (SI) change from admission to discharge during hospitalization at the APCU?

Methods

Design

A prospective longitudinal study was conducted among inpatients at an APCU in a tertiary cancer clinic. All hospitalized patients admitted between January 15, 2019 and January 15, 2020 were assessed. With a dedicated organizational focus on systematic symptom assessment, clinical practice based on commonly accepted palliative care principles was carried out as usual [12].

Organization of the APCU

The APCU comprises a 12-bed ward and an outpatient clinic at the Cancer Clinic, St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Norway. The Cancer Clinic is an ESMO designated Centre of Integrated Oncology and Palliative Care. The senior consultants at the APCU are oncologists with specialized training in palliative care and attend the Cancer Clinic’s common day-to-day activities, such as joint meetings and internal teaching. A residency in oncology includes at least 6 months of compulsory service at the APCU, where the majority of the nurses are trained in both oncology and palliative care.

The multidisciplinary team (MDT) at the APCU consists, in addition to physicians and nurses, of physiotherapists, occupational therapists, chaplains, social workers, and a clinical dietitian. Patients are followed up by specific professions or by the entire MDT.

Patients

Adult patients with incurable cancer are referred to the APCU. Patients with hematological, gynecological, and pulmonary malignancies, and receiving treatment at their respective university hospital departments, are only referred when in need of neuraxial pain management. Patients on systemic cancer therapy and in need of palliative care are included in an integrated care pathway, and follow-up is a shared responsibility of the treating oncologist and the palliative care team. The oncologist is responsible for the tumor-directed treatment, while the palliative care physician is in charge of the symptom management. Joint consultations are encouraged and the patient perspective is paramount in the decision-making process regarding further treatment plans. However, the bulk of the patients are included in a “palliative care pathway” and solely treated by the palliative care team.

Assessments and data collection

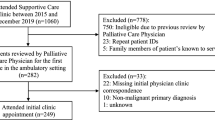

For the study purpose, the term “intervention” included diagnostic imaging, medical treatments, therapeutic and interventional radiology, surgery, and multidisciplinary follow-up. All consecutive admissions were assessed to describe the use of interventions during hospitalization. For the evaluation of symptom development, only unique patients with symptom registrations at admission and at discharge were included (Fig. 1).

The patients reported average SI past 24 h on the 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS 0–10) [26]. Daily PROMs were recorded on a paper-based form, and included the symptoms pain, tiredness, drowsiness, nausea, appetite, shortness of breath, depression, anxiety, well-being, constipation, and sleep [27]. In addition, worst pain intensity the past 24 h was assessed (NRS 0–10) [28, 29].

Physician-reported patient information included gender, age, cancer diagnosis, metastatic status, and medical comorbidity. Additionally, information on care pathway, interventions, and place of care after discharge was recorded.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was applied for demographics, clinical data, and the use of interventions.

NRS = 0 indicated no symptoms, whereas mild SI was defined as scores of 1–3, and moderate to severe SI defined as scores of ≥ 4 (NRS 0–10) [26]. An absolute NRS reduction ≥ 1 during the hospital stay was considered a clinically important difference [30].

For all symptoms assessed, the paired sample t-test was used to compare SI at admission and at discharge.

For patients admitted more than once, only the first admission to the APCU was included in the analyses of symptom development, due to considerations on independent variables. Single imputations with last value carried forward were performed for patients with missing data at discharge.

The difference in symptom burden at admission and at discharge for patients included in the “integrated care pathway” and the “palliative care pathway,” respectively, was compared using the independent samples t-test.

Normal distribution was verified by visual inspection of Q-Q plots. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics

The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics, Health Region Central Norway (REK) (2018/925/REK midt) defined the project as healthcare improvement, without the need for explicit informed consent from the patients.

Results

Four hundred fifty-one admissions were registered during the 1-year study period, of which 302 (67%) were emergency admissions. Elective admissions and referrals from other hospital departments were equally distributed among the remaining. Mean hospital length of stay was 7.0 days (Table 1). Two hundred sixty (58%) of the patients were discharged to home care, 122 (27%) to nursing homes, and 57 (13%) died during hospitalization. Only a small fraction of the patients was discharged to other hospitals. One hundred ninety-five (43%) of the 451 hospitalizations were readmissions.

Baseline patient characteristics are described in Table 1. Mean age was 69 years and 60% were males. Gastrointestinal, urological, and breast cancer were the most frequent cancer diagnoses. Most patients were either married or cohabitant, and the vast majority had metastases and comorbidities. More than one-third of the patients were included in the “integrated care pathway”.

Interventions

Diagnostic and therapeutic interventions (other than medical adjustments) during the 451 hospitalizations are displayed in Table 2. Diagnostic imaging was performed in 66% of the hospital stays. Computer tomography and plain X-rays were the most commonly used modalities. Intravenous rehydration was administered to 45% of the admitted patients, while 37% and 32% received antibiotics and any medical nutrition therapy, respectively. The MDT was involved in the follow-up of 39% of the patients. Most frequently, the physiotherapist was involved, followed by the occupational therapist, social worker, chaplain, and clinical dietitian.

Medical adjustments are reported in Table 3. At admission, 55% of the patients received oral opioids and 27% subcutaneous opioids. At discharge, the corresponding numbers were 44% and 45%, respectively. Ten percent of the patients did not receive opioids at admission. Dosing was adjusted for 68% of the patients using opioids and represented the most frequent medication adjustment. At admission, 69% of the patients received laxatives, 54% corticosteroids, and 53% antiemetics. At discharge, the corresponding numbers were 70%, 63%, and 59%, respectively.

Symptom development

PROMs at first admission and at first discharge were available for 180 unique patients (Fig. 1, Table 4). At admission, patient-reported tiredness yielded highest mean SI score (5.6, NRS 0–10), followed by worst pain and drowsiness (both 5.2), whereas the lowest mean SI was reported for nausea (2.2). Statistically significant reductions were reported for all assessed SIs during the hospital stay (p ≤ 0.01), and clinically important reductions (SI reduction ≥ 1, NRS 0–10) were reported for worst pain, tiredness, constipation, average pain, well-being, drowsiness, and appetite. For the subgroup of patients with moderate to severe SIs (NRS 4–10) at admission, both statistically significant and clinically important reductions in SI were reported for all assessed symptoms (Table 5).

Patients included in the “integrated care pathway” reported higher worst pain intensities at admission compared to patients included in the “palliative care pathway” (mean SI 5.7 vs. 4.7, respectively, p = 0.03). For all other symptoms, there were no statistically significant differences in SIs at admission for patients included in the two respective care pathways. Furthermore, drowsiness improved more during hospitalization for patients included in the “integrated care pathway” (mean 1.7 points vs. 0.6 points (NRS 0–10), respectively, p = 0.03). For all other symptoms, there were no statistically significant differences in symptom development during the hospital stay for patients included in the two respective care pathways.

Discussion

The study provided a comprehensive description of interventions during hospitalization at an APCU. The evaluated patients experienced relief for all assessed symptoms, with the larger effect sizes for patients with moderate and severe SIs. Patients receiving systemic cancer therapy reported symptom relief similar to patients not on systemic cancer therapy. Most patients received opioids at admission, and the majority needed opioid dose adjustments during hospitalization.

Patient demographics in the current study are comparable to reports from other APCUs [20, 31]. Almost 40% of the admitted patients were included in the “integrated care pathway,” an approach in line with recommendations from stakeholders and the World Health Organization [12, 32].

Appraisal of methods

All consecutive admissions to an APCU during 1 year were recorded, and the study provided an unselected registration of interventions applied during hospitalization. Thus, the interventions reflect daily practice.

Symptom development was registered for only a fraction of the admissions and patients with severely reduced cognitive or physical function were not included, making the results prone to selection bias. In addition, the study provides no inference of causality between interventions and symptom relief. Furthermore, the study-related organizational focus on systematic symptom assessment may have resulted in an overestimation of daily practice symptom relief.

The single-center, one-group study design opens for systematic errors [33]. Local organizational structures and the inclusion of few patients with hematological, gynecological, and pulmonary malignancies limit the study’s generalizability.

Almost three-quarters of the patients had comorbidities. The number and severity of comorbidities were not specified, and the reported symptoms may have been caused by conditions other than the cancer or the cancer treatment [34]. The 11-point numeric rating scale provides information on SI. Sometimes a more comprehensive assessment may be needed, e.g. when evaluating symptoms like depression and anxiety [35]. Additionally, important palliative care outcomes like patient and family satisfaction were not assessed.

Interventions

The majority of the admitted patients underwent diagnostic imaging, almost 40% received antibiotics, and two-thirds needed opioid dose adjustments to achieve pain control. In addition, many patients received other medical interventions, such as fluid therapy, nutrition, and blood transfusions. Furthermore, a considerable number were treated with radiotherapy, radiological interventions, or surgery. The abovementioned, and the high number of emergency admissions, emphasizes the patient population’s needs and demands for urgent hospital care, or emergency palliative care.

Only few studies evaluate the diagnostic and therapeutic interventions used at an APCU. A study of 42 patients admitted to the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center reported comparable use of medications for symptom relief, but more use of interventional procedures [36]. The study design makes comparison difficult and inferring whether our practice represents overtreatment or undertreatment even more so. Still, a critical focus on potentially non-beneficial procedures at the end of life, especially the use of diagnostic imaging and treatment of infections, is necessary [25].

Although participants of the MDT followed up approximately 40% of the patients, involvement from the entire team was less frequent. One might argue that the relatively limited use of the MDT represents undertreatment [32]. On the other hand, most of the patients were prior to admission APCU outpatients, already introduced to the MDT, and not necessarily in need of its attention during the hospital stay. Despite a lack of studies exploring its impact in a controlled framework, the MDT is considered a cornerstone in palliative care. In our study, a quantification of the effect of the MDT on symptom relief was not possible.

Symptom development

The patient-reported symptom burden at admission was comparable to previous reports from palliative care units [2, 19, 20]. Moreover, the reductions in symptom scores were in line with other studies exploring symptom development during hospitalization [19,20,21]. Symptoms like tiredness, drowsiness, well-being, lack of appetite, and dyspnea may be difficult to alleviate at the end of life [3, 37]. We included patients earlier in the disease trajectory, possibly contributing to the favorable results.

For patients with moderate to severe SIs, large improvements were reported for constipation, nausea, pain, and sleep. With several available drugs for symptom relief, there might be an enhanced focus on these specific symptoms. The improvement in well-being of two points might reflect the comprehensive care offered. Rehydration and treatment of infections may contribute, as well as the general care and family involvement.

Interestingly, the symptom burdens at admission for patients included in the “integrated care pathway” and the “palliative care pathway,” respectively, were equal and worst pain intensity even higher for patients receiving integrated care. In addition, SI reductions were similar for patients included in the two respective care pathways, except for drowsiness, which decreased more for “integrated care pathway” patients. Although some of the assessed symptoms may represent adverse effects of cancer treatment, even patients relatively early in the cancer disease trajectory seemed to benefit from hospitalization at the APCU. This corresponds with previous studies, in which symptom self-reporting during cancer treatment was associated with clinical benefits and increased survival [13, 38].

Implications and further studies

The study demonstrated reduced SIs for hospitalized patients assessed with PROMs and receiving palliative care. Studies aiming to evaluate the effect of specific interventions may utilize the results for sample size calculations.

Worst pain past 24 h differed significantly from average pain past 24 h. Reducing worst SIs is a treatment goal, and a dynamic comparison of worst and average SIs during hospitalization might be addressed in future research. Additionally, the most intense symptoms may not necessarily be the most bothersome [39]. This aspect also needs more attention.

Finally, the regular daily practice yielded symptom relief. A supplementary decision support system may contribute positively, but further studies are warranted [29, 40].

Conclusions

The study described the practice and clinically meaningful symptom relief during hospitalization at an APCU. Improvements were similar for patients on systemic cancer therapy and palliative care patients, supporting a benefit of early integration of palliative care into cancer care.

Data availability

The corresponding author has full control of all primary data. The dataset generated and/ or analyzed are available from the corresponding author on request.

Code availability

N/A.

References

Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, de Haes HC, Voest EE, de Graeff A (2007) Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 34(1):94–104

Laugsand EA, Kaasa S, de Conno F, Hanks G, Klepstad P (2009) Intensity and treatment of symptoms in 3,030 palliative care patients: a cross-sectional survey of the EAPC Research Network. J Opioid Manag 5(1):11–21

Seow H, Barbera L, Sutradhar R, Howell D, Dudgeon D, Atzema C et al (2011) Trajectory of performance status and symptom scores for patients with cancer during the last six months of life. J ClinOncol 29(9):1151–1158

van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J (2007) Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol 18(9):1437–1449

van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, Hochstenbach LM, Joosten EA, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Janssen DJ (2016) Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 51(6):1070-1090 e9

Thronaes M, Raj SX, Brunelli C, Almberg SS, Vagnildhaug OM, Bruheim S et al (2016) Is it possible to detect an improvement in cancer pain management? A comparison of two Norwegian cross-sectional studies conducted 5 years apart. Support Care Cancer 24(6):2565–2574

Verkissen MN, Hjermstad MJ, Van Belle S, Kaasa S, Deliens L, Pardon K (2019) Quality of life and symptom intensity over time in people with cancer receiving palliative care: results from the international European Palliative Care Cancer Symptom study. PLoS ONE 14(10):e0222988

Kwon JH (2014) Overcoming barriers in cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol 32(16):1727–1733

Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD (2012) Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA 307(14):1513–1516

Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG (2007) The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med 357(6):608–613

Berwick DM (2017) Avoiding overuse-the next quality frontier. Lancet 390(10090):102–104

Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, Albreht T, Anderson R, Bruera E et al (2018) Integration of oncology and palliative care: a Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol 19(11):e588–e653

Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, Scher HI, Kris MG, Hudis C et al (2017) Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 318(2):197–198

Rhondali W, Hui D, Kim SH, Kilgore K, Kang JH, Nguyen L et al (2012) Association between patient-reported symptoms and nurses’ clinical impressions in cancer patients admitted to an acute palliative care unit. J Palliat Med 15(3):301–307

Gravis G, Marino P, Joly F, Oudard S, Priou F, Esterni B et al (2014) Patients’ self-assessment versus investigators’ evaluation in a phase III trial in non-castrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15). Eur J Cancer 50(5):953–962

Kaasa S, Apolone G, Klepstad P, Loge JH, Hjermstad MJ, Corli O et al (2011) Expert conference on cancer pain assessment and classification-the need for international consensus: working proposals on international standards. BMJ Support Palliat Care 1(3):281–287

Haugen DF, Hjermstad MJ, Hagen N, Caraceni A, Kaasa S (2010) Assessment and classification of cancer breakthrough pain: a systematic literature review. Pain 149(3):476–482

Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K (1991) The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 7(2):6–9

Modonesi C, Scarpi E, Maltoni M, Derni S, Fabbri L, Martini F et al (2005) Impact of palliative care unit admission on symptom control evaluated by the Edmonton symptom assessment system. J Pain Symptom Manage 30(4):367–373

Mercadante S, Adile C, Caruselli A, Ferrera P, Costanzi A, Marchetti P et al (2016) The palliative-supportive care unit in a comprehensive cancer center as crossroad for patients’ oncological pathway. PLoS ONE 11(6):e0157300

Tai SY, Lee CY, Wu CY, Hsieh HY, Huang JJ, Huang CT et al (2016) Symptom severity of patients with advanced cancer in palliative care unit: longitudinal assessments of symptoms improvement. BMC Palliat Care 15:32

Hui D, Elsayem A, Palla S, De La Cruz M, Li Z, Yennurajalingam S et al (2010) Discharge outcomes and survival of patients with advanced cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 13(1):49–57

Hui D, Cherny NI, Wu J, Liu D, Latino NJ, Strasser F (2018) Indicators of integration at ESMO Designated Centres of Integrated Oncology and Palliative Care. ESMO Open 3(5):e000372

Hui D, Cherny N, Latino N, Strasser F (2017) The ‘critical mass’ survey of palliative care programme at ESMO designated centres of integrated oncology and palliative care. Ann Oncol 28(9):2057–2066

Cardona-Morrell M, Kim J, Turner RM, Anstey M, Mitchell IA, Hillman K (2016) Non-beneficial treatments in hospital at the end of life: a systematic review on extent of the problem. Int J Qual Health Care 28(4):456–469

Hui D, Bruera E (2017) The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System 25 years later: past, present, and future developments. J Pain Symptom Manage 53(3):630–643

Hannon B, Dyck M, Pope A, Swami N, Banerjee S, Mak E et al (2015) Modified Edmonton Symptom Assessment System including constipation and sleep: validation in outpatients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 49(5):945–952

Lohre ET, Klepstad P, Bennett MI, Brunelli C, Caraceni A, Fainsinger RL et al (2016) From “breakthrough” to “episodic” cancer pain? A European Association for Palliative Care Research Network Expert Delphi Survey toward a common terminology and classification of transient cancer pain exacerbations. J Pain Symptom Manage 51(6):1013–1019

Lohre ET, Thronaes M, Brunelli C, Kaasa S, Klepstad P (2019) An in-hospital clinical care pathway with integrated decision support for cancer pain management reduced pain intensity and needs for hospital stay. Support Care Cancer 28:671–682

Hui D, Shamieh O, Paiva CE, Perez-Cruz PE, Kwon JH, Muckaden MA et al (2015) Minimal clinically important differences in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale in cancer patients: a prospective, multicenter study. Cancer 121(7):3027–3035

Hausner D, Kevork N, Pope A, Hannon B, Bryson J, Lau J et al (2018) Factors associated with discharge disposition on an acute palliative care unit. Support Care Cancer 26(11):3951–3958

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO definition of palliative care [Available from: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/]. Accessed 30 Oct 2020

Kacha AK, Nizamuddin SL, Nizamuddin J, Ramakrishna H, Shahul SS (2018) Clinical study designs and sources of error in medical research. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 32:2789–2801

Hui D, Abdelghani E, Chen J, Dibaj S, Zhukovsky D, Dev R et al (2020) Chronic non-malignant pain in patients with cancer seen at a timely outpatient palliative care clinic. Cancers (Basel) 12(1):214

Brenne E, Loge JH, Lie H, Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Kaasa S et al (2016) The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System: poor performance as screener for major depression in patients with incurable cancer. Palliat Med 30(6):587–598

Elsayem A, Calderon BB, Camarines EM, Lopez G, Bruera E, Fadul NA (2011) A month in an acute palliative care unit: clinical interventions and financial outcomes. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 28(8):550–555

Tsai JS, Wu CH, Chiu TY, Hu WY, Chen CY (2006) Symptom patterns of advanced cancer patients in a palliative care unit. Palliat Med 20(6):617–622

Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, Scher HI, Hudis CA, Sabbatini P et al (2016) Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 34(6):557–565

Li B, Mah K, Swami N, Pope A, Hannon B, Lo C et al (2019) Symptom assessment in patients with advanced cancer: are the most severe symptoms the most bothersome? J Palliat Med 22(10):1252–1259

Raj SX, Brunelli C, Klepstad P, Kaasa S (2017) COMBAT study-computer based assessment and treatment-a clinical trial evaluating impact of a computerized clinical decision support tool on pain in cancer patients. Scand J Pain 17:99–106

Funding

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Morten Thronæs, Erik Torbjørn Løhre, Anne Kvikstad, Elisabeth Brenne, Robin Norvaag, Kathrine Otelie Aalberg, Martine Kjølberg Moen, Gunnhild Jakobsen, Pål Klepstad, Arne Solberg, and Tora Skeidsvoll Solheim. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Morten Thronæs, Erik Torbjørn Løhre, and Tora Skeidsvoll Solheim and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This project was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was applied for and considered by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics, Health Region Central Norway (REK) (2018/925/REK midt) (28.06.2018). The project was considered a health improvement project and no further approval was needed. Informed consent was considered not necessary by REK.

Consent to participate

N/A.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thronæs, M., Løhre, E.T., Kvikstad, A. et al. Interventions and symptom relief in hospital palliative cancer care: results from a prospective longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer 29, 6595–6603 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06248-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06248-z