Abstract

Purpose

Cancer navigation improves access to support and reduces barriers to care; however, appropriate training of navigators is essential. We developed the TrueNTH Peer Navigation Training Program (PNTP), a competency-based, blended online/in-person course. In this study, we evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of the PNTP among prostate cancer (PC) survivors (patients, caregivers).

Methods

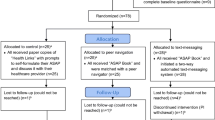

We employed an explanatory mixed method study design consisting of course usage data, pre-/post-questionnaires, and focus groups informed by the Kirkpatrick framework and self-efficacy theory.

Results

Three cohorts in two Canadian cities (n = 26) received the PNTP. Participants were motivated to support others like themselves (n = 20), fill a gap (n = 7), pay it forward (n = 6), and offer expertise (n = 4). Recruitment, retention, and questionnaire completion were 96.7%, 89.6%, and 92%. Participants contributed a total of 426 posts to the online forums (2 to 3 posts per participant/module). Satisfaction was 9.4/10 (SD = 0.7) and usability was 84.5/100 (SD = 10.1). All learning outcomes increased: understanding of learning objectives t(23) = − 6.12, p < 0.0001; self-efficacy to perform competencies t(23) = − 4.8, p < 0.0001; and eHealth literacy t(23) = − 4.4, p < 0.0001. Participants viewed the PTNP as intensive but manageable, improving knowledge and confidence and enhancing listening skills. Participants valued the flexibility of online learning, interactive online learning, in-person interactions for relationship building, and authentic role-playing for skill development.

Conclusions

A facilitated online training program with in-person components is a highly acceptable and effective format to train PC survivors to become peer navigators. This competency-based peer navigator training program and delivery format may serve as a useful model for other cancer volunteer programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E (2006) From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, DC

Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, Arora NK, Rowland JH (2017) Going beyond being lost in transition: a decade of progress in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol 35(18):1978–1981

Canadian Paternship Against Cancer (2015) Prostate cancer control in Canada: a system performance spotlight report. Toronto, ON

Canadian Paternership Against Cancer (2018) Living with cancer: a report on the patient experience. Toronto, ON

Paterson C, Robertson A, Smith A, Nabi G (2015) Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs 19(4):405–418

King AJL, Evans M, Moore THM, Paterson C, Sharp D, Persad R, Huntley AL (2015) Prostate cancer and supportive care: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis of men’s experiences and unmet needs. Eur J Cancer Care 24(5):618–634

Lopez D, Pratt-Chapman ML, Rohan EA, et al. (2019) Establishing effective patient navigation programs in oncology. Support Care Cancer :1–12

Canadian Parntership Against Cancer (2012) Navigation: a guide to implementing best practices in person-centred care. Toronto, ON

Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, Garcia R, Greene A, Calhoun E, Mandelblatt JS, Paskett ED, Raich PC, the Patient Navigation Research Program (2008) Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 113(8):1999–2010

Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ (2011) Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J Clin 61(4):237–249

Tan CHH, Wilson S, McConigley R (2015) Experiences of cancer patients in a patient navigation program: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 13(2):136–168

Ustjanauskas AE, Bredice M, Nuhaily S, Kath L, Wells KJ (2016) Training in patient navigation. Health Promot Pract 17(3):373–381

Willis A, Reed E, Pratt-Chapman ML, Kapp H (2013) Development of a framework for patient navigation: delineating roles across navigator types. J Oncol Navig Surviv. 4(6)

Lorhan S, Cleghorn L, Fitch M, Pang K, McAndrew A, Applin-Poole J, Ledwell E, Mitchell R, Wright M (2013) Moving the agenda forward for cancer patient navigation: understanding volunteer and peer navigation approaches. J Cancer Educ 28(1):84–91

Lorhan S, Wright M, Hodgson S, van der Westhuizen M (2014) The development and implementation of a volunteer lay navigation competency framework at an outpatient cancer center. Support Care Cancer 22(9):2571–2580

McMullen L, Banman T, De Goort J, Jacobs S, Srdanovic D, Mackey H (2013) Oncology nurse navigator competencies: providing direction to imorove care delivery. In: 4th Annual Conference of the Academcy of Oncology Nurse Navigators. Memphis

Pratt-Chapman M, Willis A, Masselink L (2015) Core competencies for oncology patient navigators. J Oncol Navig Surviv 6(2):16–24

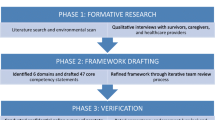

Flora PK, Bender JL, Miller AS, Parvin L, Soheilipour S, Maharaj N, Milosevic E, Matthew A, Kazanjian A (2020) A core competency framework for prostate cancer peer navigation. Support Care Cancer 28(6):2605–2614

Kashima K, Phillips S, Harvey A, Van Kirk VA, Pratt-Chapman M (2018) Efficacy of the competency-based oncology patient navigator training. J Oncol Navig Surviv 9(12):519–524

Canadian Cancer Society. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2019. Toronto, ON; 2019

Sinfield P, Baker R, Ali S, Richardson A (2012) The needs of carers of men with prostate cancer and barriers and enablers to meeting them: a qualitative study in England. Eur J Cancer Care 21(4):527–534

Bender JL, Feldman-Stewart D, Tong C, Lee K, Brundage M, Pai H, Robinson J, Panzarella T (2019) Health-related internet use among men with prostate cancer in Canada: cancer registry survey study. J Med Internet Res 21(11):e14241

Means B, Toyama Y, Murphy R, Baki M (2013) The effectiveness of online and blended learning: a meta-analysis of the emprical literature. Teach Coll Rec 115(3):030303

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL (2011) Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE Publications

Kirkpatrick D (1994) Evaluating training programs: the four levels. Berret-Koehler, San Francisco

Bandura A Self efficacy. The exercise of control. New York, New York, USA: W.H. Freeman and Company

Norman CD, Skinner HA (2006) eHEALS: the eHealth literacy scale. J Med Internet Res 8(4):e27

Maharaj N, Soheilipour S, Bender JL, Kazanjian A (2018) Understanding prostate cancer patients’ support needs: how do they manage living with cancer? Illness, Cris Loss. 105413731876872

Brooke J (1986) SUS - A quick and dirty system usability scale. Usability.gov

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Butow P, Ussher J, Kirsten L, Hobbs K, Smith K, Wain G, Sandoval M, Stenlake A (2006) Sustaining leaders of cancer support groups. Soc Work Health Care 42(2):39–55

Pomery A, Schofield P, Xhilaga M, Gough K (2016) Skills, knowledge and attributes of support group leaders: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 99(5):672–688

Pomery A, Schofield P, Xhilaga M, Gough K (2017) Pragmatic, consensus-based minimum standards and structured interview to guide the selection and development of cancer support group leaders: a protocol paper. BMJ Open 7(6):e014408

Carroll JK, Humiston SG, Meldrum SC, Salamone CM, Jean-Pierre P, Epstein RM, Fiscella K (2010) Patients’ experiences with navigation for cancer care. Patient Educ Couns 80(2):241–247

Phillips S, Nonzee N, Tom L, Murphy K, Hajjar N, Bularzik C, Dong X, Simon MA (2014) Patient navigators’ reflections on the navigator-patient relationship. J Cancer Educ 29(2):337–344

Bates T, Desbiens B, Donovan T, et al. (2017) Tracking online distance education in Canadian universities and colleges: 2017. Vancouver, BC

Statistics Canada (2017) Life in the fast lane: how are Canadians managing?Statistics Canada, Ottawa

Vygotsky L (1978) Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Young C (2013) Community management that works: how to build and sustain a thriving online health community. J Med Internet Res 15(6):e119

Lin Y-T, Chen M-P, Chang C-H, Chang P-C (2017) Exploring the peer interaction effects on learning achievement in a social learning platform based on social network analysis. Int J Distance Educ Technol 15(3):65–85

Park A, Hartzler AL, Huh J, Hsieh G, McDonald DW, Pratt W (2016) “How did we get here?”: topic drift in online health discussions. J Med Internet Res 18(11):e284

Clark RE (1983) Reconsidering research on learning from media. Rev Educ Res 53(4):445–459

Lim D, Morris ML, Kupritz V (2007) Online vs. blended learning: differences in instructional outcomes and learner satisfaction. J Asynchronous Learn Netw 11(2):27–42

Grembowski D (2001) The practice of health program evaluation. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Mays N, Pope C (1995) Rigor and qualitative research. Bmj. 311:109–112

Acknowledgments

This research was awarded by Prostate Cancer Canada and is proudly funded by the Movember Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bender, J.L., Flora, P.K., Milosevic, E. et al. Training prostate cancer survivors and caregivers to be peer navigators: a blended online/in-person competency-based training program. Support Care Cancer 29, 1235–1244 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05586-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05586-8