Abstract

Introduction

The EORTC QLQ-CR29 is a patient-reported outcome measure to evaluate health-related quality of life among colorectal cancer patients in research and clinical practice. The aim of this systematic review was to investigate whether the initial positive results regarding the measurement properties of the QLQ-CR29 are confirmed in subsequent studies.

Methods

A systematic search of Embase, Medline, PsycINFO, and Web of Science was conducted to identify studies investigating the measurement properties of the QLQ-CR29 published up to January 2019. For the 11 included studies, data were extracted, methodological quality was assessed, results were synthesized, and evidence was graded according to the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) methodology on the measurement properties: structural validity, internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, construct validity (hypothesis testing, including known-group comparison, convergent and divergent validity), cross-cultural validity, and responsiveness.

Results

Internal consistency was rated as “sufficient,” with low evidence. Reliability was rated as “insufficient,” with moderate evidence. Construct validity (hypothesis testing; known-group comparison, convergent and divergent validity) was rated as “inconsistent,” with moderate evidence. Structural validity, measurement error, and responsiveness were rated as “indeterminate” and could therefore not be graded.

Conclusion

This review indicates that current evidence supporting the measurement properties of the QLQ-CR29 is limited. Additionally, better quality research is needed, taking into account the COSMIN methodology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most prevalent cancers worldwide [1]. CRC and its treatment can have a large impact on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [2]. It is important to assess HRQOL in clinical trials to investigate the impact of a treatment on HRQOL, and in clinical practice to detect and monitor symptoms and offer optimal care [3,4,5]. A frequently used patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) to evaluate HRQOL in cancer patients is the 30-item European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Core Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) [6, 7] and its tumor-specific questionnaire modules [8]. In 1999, the 38-item module for CRC patients was developed (EORTC QLQ-CR38) [9], and in 2007, the module was revised and shortened to 29 items (EORTC QLQ-CR29) [10]. The initial validation study of the QLQ-CR29 in an international sample of CRC patients [11] showed that it had good internal consistency (α > 0.70) in all but one subscale, was acceptably reliable (intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) > 0.68 for subscales and > 0.55 for single items), was able to discriminate between known groups (patients with and without stoma, Karnofsky performance score < 80 and > 80, and with curative and palliative treatment), and had good divergent validity, i.e., low correlation with QLQ-C30 items [11].

Two systematic reviews on the measurement properties of the QLQ-CR29 were published in 2015 and 2016 [12, 13]. Wong et al. performed a systematic review on various disease-specific and generic HRQOL PROMs, and included two studies on the QLQ-CR29. They recommended the QLQ-CR38 to assess HRQOL in CRC patients, because it had the most positive ratings on the measurement properties according to their quality assessment criteria [12]. Ganesh et al. performed a systematic review of three CRC-specific PROMs (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C), QLQ-CR38, and QLQ-CR29), and included three studies on the QLQ-CR29. They concluded that the choice for one of these three instruments depends on the context and the research aim [13].

Since these reviews, several new validation studies of the QLQ-CR29 have been published. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to perform a systematic review of the measurement properties of the QLQ-CR29 as investigated in validation studies up to 2019, according to the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) criteria [14, 15], and to investigate whether the initial positive results regarding the measurement properties of the QLQ-CR29 are confirmed.

Materials and methods

EORTC QLQ-CR29

The EORTC QLQ-CR29 is a tumor-specific HRQOL questionnaire module for CRC patients, which is designed to complement the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire [6, 10]. The QLQ-CR29 has five functional and 18 symptom scales. It contains four subscales (urinary frequency (UF), blood and mucus in stool (BMS), stool frequency (SF), and body image (BI)) and 19 single items (urinary incontinence, dysuria, abdominal pain, buttock pain, bloating, dry mouth, hair loss, taste, anxiety, weight, flatulence, fecal incontinence, sore skin, embarrassment, stoma care problems, sexual interest (men), impotence, sexual interest (women), and dyspareunia) [11]. Patients are asked to indicate their symptoms during the past week(s). Scores can be linearly transformed to provide a score from 0 to 100. Higher scores represent better functioning on the functional scales and a higher level of symptoms on the symptom scales [10, 11].

Literature search

The literature search was part of a larger systematic review (Prospero ID 42017057237) [16], investigating the validity of 39 PROMs measuring HRQOL of cancer patients included in an eHealth self-management application “Oncokompas” [17,18,19,20,21]. We performed a systematic search of Embase, Medline, PsycINFO, and Web of Science, to identify studies investigating the measurement properties of these 39 PROMs, including the QLQ-CR29. The search terms were the PROM’s name, combined with search terms for cancer, and a precise filter for measurement properties [22]. The full search terms can be found in Appendix. The literature search was performed in June 2016 and updated in January 2019 to search for recent studies on the QLQ-CR29 specifically. References of included studies have been checked for additional articles manually.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: reporting original data from cancer patients on at least one measurement property of the QLQ-CR29, as defined in the COSMIN taxonomy [15, 23, 24]—structural validity (the degree to which the scores of a PROM are an adequate reflection of the dimensionality of the construct to be measured), internal consistency (the degree of interrelatedness among items), reliability (the extent to which scores of patients who have not changed are the same for repeated measures on different occasions), measurement error (the error of a patient’s score that is not attributed to true changes in the construct to be measured), construct validity (hypothesis testing; including known-group comparison, convergent and divergent validity [the degree to which the scores of a PROM are consistent with hypotheses with regard to differences between relevant groups, and relationships to scores of other instruments, respectively]), cross-cultural validity (the degree to which the performance of the items on a translated or culturally adapted PROM are an adequate reflection of the performance of the items of the original version of the PROM), and responsiveness (the ability of a PROM to detect change over time in the construct to be measured) [24]. Exclusion criteria were as follows: no availability of full-text manuscripts, conference proceedings, and non-English publications. Titles and abstracts, and eligible full texts were screened by two of the four raters independently (KN, FJ, AH, NH). Disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

For each reported measurement property defined by the COSMIN taxonomy [25], data were extracted by two of the four extractors independently (KN, FJ, AH, NH). This included type of measurement property, its outcome, and information on methodology. Disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached.

Data synthesis

For the data synthesis, we followed the three steps of the COSMIN guideline for systematic review of PROMs [26]. In step 1, we rated methodological quality of the studies per reported measurement property as either “excellent,” “good,” “fair,” or “poor.” A total score was obtained by taking the lowest rating on any of the methodological aspects, according to the original COSMIN checklist [14]. In step 2, we rated the results per measurement property, by applying the COSMIN criteria for good measurement properties [26]. Results of the individual studies were rated as “sufficient,” “insufficient,” or “indeterminate” per measurement property, according to predefined criteria. Ratings from the individual studies were then qualitatively summarized into an overall rating per measurement property. Inconsistencies between studies were explored. If any explanation was found (e.g., poor methodological quality), this was taken into account in the overall rating, if no explanation was found, the overall rating was summarized as “inconsistent.” In step 3, we graded the quality of the evidence of the measurement properties, following a modified GRADE approach [26]. The overall quality of the evidence was rated as “high,” “moderate,” “low,” or “very low,” taking into account risk of bias, inconsistency of study results, imprecision, and indirectness. When a measurement property was rated as “indeterminate” in step 2, the quality of evidence could not be graded, as there was no evidence to grade. The evaluation of measurement properties was performed by two raters independently (AH, NH). Disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached.

Results

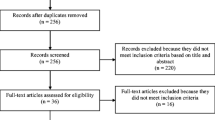

In the initial search, 980 nonduplicate abstracts were identified for all 39 PROMs, of which 31 were relevant for the QLQ-CR29. The search update resulted in 27 extra nonduplicate abstracts regarding the QLQ-CR29. In total, 55 abstracts were screened, of which 30 were excluded. Thirteen studies were excluded during full-text screening. One study was excluded during data extraction [27], because data were not presented for the QLQ-CR29 separately. The flow diagram of the literature search and selection process is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Study characteristics of the 11 included studies [11, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] are shown in Table 1. These studies reported on structural validity (9 studies), internal consistency (10 studies), reliability (6 studies), construct validity (know-group comparison [10 studies], convergent [8 studies], and divergent [2 studies] validity), and responsiveness (2 studies), but did not report on measurement error, or cross-cultural validity. However, measurement error could be calculated for four studies.

Structural validity

Nine studies investigated structural validity (Table 2). Methodological quality of eight studies was rated as “poor” [11, 28, 30,31,32, 34,35,36], because they performed multitrait item scaling (MIS) instead of exploratory/confirmatory factor analysis (EFA/CFA). One study was rated as “fair” [37], because it performed a principal component analysis (PCA). The studies reporting MIS were consistent in their findings, showing no inconsistent items regarding convergent and discriminant validity within the subscale. However, since MIS is an indirect test of structural validity, no conclusions can be drawn on the basis of these studies. In the study that used PCA, three of the four original subscales (UF, BMS, and BI) were replicated. The two-item original SF subscale was merged with four single items about bowel or stoma problems into a new subscale “defecation/stoma problems (DSP)” [37]. Because the account of variability and the ratio of the explained variance by the factors was not reported, the PCA cannot be interpreted properly, and therefore structural validity was rated as “indeterminate,” and there is no evidence for or against unidimensionality of the subscales.

Internal consistency

Ten studies investigated internal consistency (Supplementary Table 1). Methodological quality of nine studies was rated as “poor” [11, 28, 30,31,32,33,34,35,36], because evidence for unidimensionality of the subscales was not provided, and therefore, the value of Cronbach’s α could not be interpreted properly [38]. One study was rated as “fair” [37], because it did not report on how missing items were handled. This study reported good internal consistency for the BI subscale (α = 0.80), and the new subscale established (see “Structural validity”); DSP (α = 0.84). The subscale UF had adequate internal consistency (α = 0.71), and for the original subscale SF two values were presented; for patients with (α = 0.72) and without stoma (α = 0.68). The subscale BMS had low internal consistency (α = 0.56) [37]. The studies of poor quality showed mostly adequate Cronbach’s α values, except for the BMS subscale. Based on these findings, the evidence on internal consistency was rated “sufficient,” because > 75% of the values were good for the original subscales, assuming these subscales are unidimensional, which is not proven with PCA (see “Structural validity”). Quality of evidence was graded as “low,” because only one study of fair quality was found.

Reliability

Six studies investigated test–retest reliability (Table 3). Methodological quality of two studies was rated as “poor” [36, 37], because of the small sample size. Four studies were rated as “fair” [11, 30, 32, 35], because it was not reported how missing items were handled and/or had a moderate sample size. Two of these studies [11, 32] provided an overall ICC value for all subscales/items with exceptions (e.g., “ICC for all subscales was > 0.66, except for BI”), and thereby provided too little information to interpret the ICC on the subscale/item level. Low correlations (< 0.70) were reported in two remaining studies for the UF subscale, and in one of the two studies for multiple single items [30, 35]. Based on these findings, evidence on reliability was rated as “insufficient,” because of multiple unacceptable ICC values across studies. Quality of evidence was graded as “moderate,” because only studies of fair and poor quality were found.

Measurement error

None of the studies reported on measurement error. However, standard error of measurement (SEM) and smallest detectable change (SDC) could be calculated for four studies reporting on test–retest reliability [30, 35,36,37], using the ICCs and standard deviations of the subscales and single items (Supplementary Table 2). Methodological quality of two studies was rated as “fair” [30, 35], because of the moderate sample size. Two studies were rated as “poor” [36, 37], because of the small sample size. SDC scores ranged between 9.41 and 54.21, representing 9–54% of the scale of the QLQ-CR29 (0–100). However, because the minimal important change (MIC) was not reported, measurement error could not be interpreted. Based on these findings, the evidence on measurement error was rated as “indeterminate.”

Construct validity (hypothesis testing)

Known-group comparison

Ten studies performed a known-group comparison; a comparison of subgroups based on sociodemographic and/or clinical variables where differences in QLQ-CR29 scores should be expected (Table 4). Methodological quality of eight studies was rated as “poor” [11, 30,31,32,33,34,35, 37], because they did not formulate a priori hypotheses about expected differences between groups. Two studies were rated as “fair” [28, 36], because it was not described how missing items were handled. The studies of fair quality showed multiple differences in subscales and items between known-groups, but confirmed less than 75% of their hypotheses, leading to an “insufficient” rating. The studies of poor quality found multiple differences between groups (e.g., difference in taste for stoma vs. no stoma group), but careful interpretation is warranted, because no hypotheses were formulated, therefore leading to an “indeterminate” rating.

Convergent validity

Eight studies investigated convergent validity (Table 5). Methodological quality of seven studies were rated as “poor” [28, 30,31,32,33, 35, 37], because a priori hypotheses about expected correlations were not reported, and/or information on the measurement properties of the comparator instrument was not provided. One study was rated as “good” [29]. In this study, the comparator instrument was the low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) score (measuring bowel dysfunction after sphincter-preserving surgery among rectal cancer patients [29, 39]). All five of the a priori formulated hypotheses were confirmed, leading to a “sufficient” rating. In the studies of poor quality, the comparator instrument was the QLQ-C30. The QLQ-C30 is the core questionnaire of the EORTC QLQ questionnaires [6]. Most studies showed that functional subscales of the QLQ-CR29 were positively correlated with functional scales of the QLQ-C30, and negatively correlated with symptom scales of the QLQ-C30, and that most QLQ-CR29 symptom scales were positively correlated with symptom scales of the QLQ-C30, and negatively correlated with functional scales of the QLQ-C30. As there were no a priori hypotheses reported in most of these studies, results are difficult to interpret. While some scales make theoretical sense to be correlated (e.g., functional scales: QLQ-C30 emotional functioning and QLQ-CR29 anxiety), many scales are likely unrelated (e.g., symptom scales: QLQ-C30 insomnia and QLQ-CR29 hair loss). Due to the diversity of subscale constructs, the results were rated as “indeterminate” in these studies.

Divergent validity

Two studies investigated divergent validity. Methodological quality was rated as “poor” [11, 28], because a priori hypotheses about expected correlations were not reported, and information on the measurement properties of the comparator instrument was not provided. In both studies, the comparator instrument was the QLQ-C30 [6]. One study reported correlations between the two instruments of < 0.02 for most subscales [28], and the other reported correlations of < 0.40 in all subscales [11]. As was the case for convergent validity, due to the diversity of subscale constructs it is difficult to determine which subscales should be unrelated and which should be related. As such, we rated these results as “indeterminate.”

Based on these findings, construct validity (hypothesis testing) was rated overall as “inconsistent.” Most studies did not report a priori hypotheses, and therefore could not be interpreted. Three remaining studies provided an “insufficient” rating for known-group comparison [28, 36], and a “sufficient” rating for convergent validity [29], leading to the overall “inconsistent” rating. Quality of evidence was graded as “moderate,” because mostly studies of fair and poor quality were found.

Responsiveness

Two studies investigated responsiveness. Methodological quality of these studies was rated as “poor” [11, 33], because a priori hypotheses about changes in scores were not reported. Sensitivity to measure change in HRQOL was tested in patients before and within 2 years after stoma closure, and in patients receiving palliative chemotherapy and 3 months later [11], and before and after neoadjuvant or palliative chemotherapy [33]. A statistically significant reduction was found of the symptoms scores on weight [11], and BMS, SF, urinary frequency, urinary incontinence, dysuria, buttock pain, bloating, and taste [33] after chemotherapy. Other scores were unchanged, as was the case after stoma closure. Based on these findings and the fact that no correlations with changes in instruments measuring related constructs were reported, the evidence on responsiveness was rated “indeterminate.”

Summarized ratings of the results and the overall quality of evidence of all measurement properties are shown in Table 6.

Discussion

The QLQ-CR29 is a well-known and commonly used PROM, which was published in 2007, following revision of the QLQ-CR38. Both instruments cover a wide range of symptoms among CRC patients. This review shows that current evidence on the measurement properties of the QLQ-CR29 is limited. For each of the 11 studies included in the review, methodological quality per measurement property was rated most often as “fair” or “poor.” Evidence of internal consistency was rated as “sufficient,” reliability as “insufficient,” construct validity (hypotheses testing) as “inconsistent,” and structural validity, measurement error, and responsiveness as “indeterminate.”

Most studies performed indirect measurements of structural validity. With PCA, one of the original subscales could not be confirmed but was changed into a new subscale [37]. We recommend future studies to perform CFA, to confirm either the original or newly found factor structure. Subsequently, internal consistency should be assessed on those subscales that are confirmed to be unidimensional.

Reliability appears to be a concern for the QLQ-CR29. Further investigation is necessary, using ICC to control for systematic error variance. These data can also be used to assess measurement error, by calculating SDC. The SDC should be compared with the MIC, in order to determine whether the smallest change in scores that can be detected is smaller than the change that is minimally important for patients, and is not due, with 95% certainty, to measurement error.

Criterion validity cannot be assessed for the QLQ-CR29, since there is no “gold standard” for measuring HRQOL. Therefore, it is important to assess construct validity by formulating hypotheses, a priori, for (1) known-group differences and (2) assessing convergent and divergent validity with other PROMs, including direction and magnitude. Hypotheses that can be confirmed contribute to construct validity. The aim of the studies included in this review was primarily to determine whether there was overlap between the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CR29, and not to specifically test for convergent/divergent validity. Therefore, construct validity of the QLQ-CR29 needs to be investigated further with a priori formulated hypotheses. The same applies to responsiveness, which needs to be investigated in groups that are known to change, with a priori formulated hypotheses.

While none of the studies reported on tests of cross-cultural validity (i.e., measurement invariance), the original validation study was performed in an international sample [11]. Additional, formal tests of measurement invariance would be useful.

The strength of the current review is that we closely followed the COSMIN guidelines during all steps of this review. A limitation is that we used a precise instead of a sensitive search filter for measurement properties in the literature search, which has a lower sensitivity (93 vs. 97%) [22]. Therefore, we cannot rule out that some additional validation studies of the QLQ-CR29 might have been missed.

This review indicates that additional, better quality research is needed on the measurement properties of the QLQ-CR29. Future validation studies should focus on assessing structural validity and subsequently internal consistency on subscales that are unidimensional, reliability and thereby measurement error, construct validity (hypothesis testing), and responsiveness with a priori hypotheses, and cross-cultural validity. It is thereby recommended to use the COSMIN methodology.

Abbreviations

- BI:

-

Body image

- BMS:

-

Blood and mucus in stool

- COSMIN:

-

COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments

- CFA:

-

Confirmatory factor analysis

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- DSP:

-

Defecation/stoma problems

- EFA:

-

Exploratory factor analysis

- EORTC:

-

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer

- (EORTC) QLQ-C30:

-

EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire, 30-item core questionnaire

- (EORTC) QLQ-CR29:

-

EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire, 29-item colorectal specific questionnaire

- EORTC QLQ-CR38:

-

EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire, 38-item colorectal specific questionnaire

- FACT-C:

-

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal

- GRADE:

-

Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- HRQOL:

-

Health-related quality Of life

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- KPS:

-

Karnofsky performance score

- MIC:

-

Minimal important change

- MIS:

-

Multitrait item scaling

- LARS:

-

Low anterior resection syndrome

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROM:

-

Patient-reported outcome measure

- SDC:

-

Smallest detectable change

- SEM:

-

Standard error of measurement

- SF:

-

Stool frequency

- UF:

-

Urinary frequency

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F (2015) Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 136:E359–E386. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29210

Jansen L, Herrmann A, Stegmaier C, Singer S, Brenner H, Arndt V (2011) Health-related quality of life during the 10 years after diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 29:3263–3269. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.31.4013

Howell D, Molloy S, Wilkinson K, Green E, Orchard K, Wang K, Liberty J (2015) Patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer clinical practice: a scoping review of use, impact on health outcomes, and implementation factors. Ann Oncol 26:1846–1858. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv181

Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, Harrow A, di Domenico D, Croy S, MacGillivray S (2014) What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 32:1480–1501

Basch E, Snyder C, McNiff K, Brown R, Maddux S, Smith ML, Atkinson TM, Howell D, Chiang A, Wood W, Levitan N, Wu AW, Krzyzanowska M (2014) Patient-reported outcome performance measures in oncology. J Oncol Pract 10:209–211. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2014.001423

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, Haes JCJM, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 85:365–376. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365

Giesinger JM, Kieffer JM, Fayers PM, Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Scott NW, Sprangers MA, Velikova G, Aaronson NK, EORTC Quality of Life Group (2016) Replication and validation of higher order models demonstrated that a summary score for the EORTC QLQ-C30 is robust. J Clin Epidemiol 69:79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.007

Velikova G, Coens C, Efficace F, Greimel E, Groenvold M, Johnson C, Singer S, van de Poll-Franse L, Young T, Bottomley A (2012) Health-related quality of life in EORTC clinical trials - 30 years of progress from methodological developments to making a real impact on oncology practice. Eur J Cancer Suppl 10:141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6349(12)70023-X

Sprangers MAG, Te Velde A, Aaronson NK (1999) The construction and testing of the EORTC colorectal cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire module (QLQ-CR38). Eur J Cancer 35:238–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(98)00357-8

Gujral S, Conroy T, Fleissner C, Sezer O, King PM, Avery KN, Sylvester P, Koller M, Sprangers MA, Blazeby JM, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group (2007) Assessing quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer: an update of the EORTC quality of life questionnaire. Eur J Cancer 43:1564–1573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2007.04.005

Whistance RN, Conroy T, Chie W, Costantini A, Sezer O, Koller M, Johnson CD, Pilkington SA, Arraras J, Ben-Josef E, Pullyblank AM, Fayers P, Blazeby JM, European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group (2009) Clinical and psychometric validation of the EORTC QLQ-CR29 questionnaire module to assess health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 45:3017–3026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2009.08.014

Wong CKH, Chen J, Yu CLY, Sham M, Lam CLK (2015) Systematic review recommends the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer colorectal cancer-specific module for measuring quality of life in colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol 68:266–278

Ganesh V, Agarwal A, Popovic M, Cella D, McDonald R, Vuong S, Lam H, Rowbottom L, Chan S, Barakat T, DeAngelis C, Borean M, Chow E, Bottomley A (2016) Comparison of the FACT-C, EORTC QLQ-CR38, and QLQ-CR29 quality of life questionnaires for patients with colorectal cancer: a literature review. Support Care Cancer 24:3661–3668

Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, Ostelo RWJG, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW (2012) Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res 21:651–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9960-1

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, Stratford PW, Alonso J, Patrick DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW (2010) The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol 10:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-10-22

Neijenhuijs K, Verdonck-de Leeuw I, Cuijpers P, et al (2017) Validity and reliability of patient reported outcomes measuring quality of life in cancer patients. In: PROSPERO. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017057237. Accessed 18 June 2018

van der Hout A, van Uden-Kraan CF, Witte BI, Coupé VMH, Jansen F, Leemans CR, Cuijpers P, van de Poll-Franse LV, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2017) Efficacy, cost-utility, and reach of an eHealth self-management application ‘Oncokompas’ that facilitates cancer survivors to obtain optimal supportive care: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Trials 18:228. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-1952-1

Lubberding S, van Uden-Kraan CF, Te Velde EA et al (2015) Improving access to supportive cancer care through an eHealth application: a qualitative needs assessment among cancer survivors. J Clin Nurs 24:1367–1379. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12753

Duman-Lubberding S, van Uden-Kraan CF, Jansen F, Witte BI, van der Velden LA, Lacko M, Cuijpers P, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2016) Feasibility of an eHealth application “OncoKompas” to improve personalized survivorship cancer care. Support Care Cancer 24:2163–2171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3004-2

Duman-Lubberding S, Van Uden-Kraan CF, Peek N et al (2015) An eHealth application in head and neck cancer survivorship care: health care professionals’ perspectives. J Med Internet Res 17:e235. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4870

Melissant HC, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Lissenberg-Witte BI, Konings IR, Cuijpers P, van Uden-Kraan CF (2018) Oncokompas’, a web-based self-management application to support patient activation and optimal supportive care: a feasibility study among breast cancer survivors. Acta Oncol (Madr) 57:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2018.1438654

Terwee CB, Jansma EP, Riphagen II, De Vet HCW (2009) Development of a methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on measurement properties of measurement instruments. Qual Life Res 18:1115–1123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9528-5

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al (2012) COSMIN checklist manual

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW (2010) The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 63:737–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW (2010) The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 19:539–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8

Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, Alonso J, Patrick DL, de Vet HCW, Terwee CB (2018) COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 27:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1798-3

Costa ALS, Heitkemper MM, Alencar GP, Damiani LP, Silva RM, Jarrett ME (2016) Social support is a predictor of lower stress and higher quality of life and resilience in Brazilian patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Nurs 00:1–360. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000388

Arraras JI, Suárez J, Arias De La Vega F et al (2011) The EORTC quality of life questionnaire for patients with colorectal cancer: EORTC QLQ-CR29 validation study for Spanish patients. In: Clinical and translational oncology. Springer, Milan, pp 50–56

Hou X, Pang D, Lu Q, Yang P, Jin SL, Zhou YJ, Tian SH (2015) Validation of the Chinese version of the low anterior resection syndrome score for measuring bowel dysfunction after sphincter-preserving surgery among rectal cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs 19:495–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2015.02.009

Ihn MH, Lee S-M, Son IT, Park JT, Oh HK, Kim DW, Kang SB (2015) Cultural adaptation and validation of the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-CR29 in patients with colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer 23:3493–3501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2710-0

Lin J-B, Zhang L, Wu D-W, Xi ZH, Wang XJ, Lin YS, Fujiwara W, Tian JR, Wang M, Peng P, Guo A, Yang Z, Luo L, Jiang LY, Li QQ, Zhang XY, Zhang YF, Xu HW, Yang B, Li XL, Lei YX (2017) Validation of the Chinese version of the EORTC QLQ-CR29 in patients with colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 23:1891–1898. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i10.1891

Magaji BA, Moy FM, Roslani AC, Law CW, Raduan F, Sagap I (2016) Psychometric validation of the Bahasa Malaysia version of the EORTC QLQ-CR29. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 16:8101–8105. https://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.18.8101

Montazeri A, Emami AH, Sadighi S et al (2017) Psychometric properties of the Iranian version of colorectal cancer specific quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-CR29). Basic Clin Cancer Res 9:32–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx261.315

Nowak W, Tobiasz-Adamczyk B, Brzyski P, Sałówka J, Kuliś D, Richter P (2011) Adaptation of quality of life module EORTC QLQ-CR29 for polish patients with rectal Cancer—initial assessment of validity and reliability. Polish J Surg 83:502–510. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10035-011-0078-5

Sanna B, Bereza K, Paradowska D, Kucharska E, Tomaszewska IM, Dudkiewicz Z, Golec J, Bottomley A, Tomaszewski KA (2017) A large scale prospective clinical and psychometric validation of the EORTC colorectal (QLQ-CR29) module in Polish patients with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 26:e12713–e12713. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12713

Shen MH, Chen LP, Ho TF, Shih YY, Huang CS, Chie WC, Huang CC (2018) Validation of the Taiwan Chinese version of the EORTC QLQ-CR29 to assess quality of life in colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer 18:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4312-y

Stiggelbout AM, Kunneman M, Baas-Thijssen MCM, Neijenhuis PA, Loor AK, Jägers S, Vree R, Marijnen CAM, Pieterse AH (2016) The EORTC QLQ-CR29 quality of life questionnaire for colorectal cancer: validation of the Dutch version. Qual Life Res 25:1853–1858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1210-5

Cortina JM (1993) What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J Appl Psychol 78:98–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S (2012) Low anterior resection syndrome score. Ann Surg 255:922–928. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824f1c21

Acknowledgements

We thank Heleen Melissant (HM) and Nienke Hooghiemstra (NH) for the assistance with the COSMIN quality assessments.

Funding

This study was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant number VUP 2014-7202).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Highlights

• Internal consistency of the QLQ-CR29 is “sufficient”

• Reliability of the QLQ-CR29 is “insufficient”

• Construct validity of the QLQ-CR29 is “inconsistent”

• The other measurement properties were rated as “indeterminate”

Appendix. Search terms

Appendix. Search terms

Embase.com

(‘Perceived Stress Scale’/de OR ‘Insomnia Severity Index’/de OR ‘International Index of Erectile Function’/de OR ((cancer NEAR/3 worr* NEAR/3 scale*) OR (patient NEAR/3 specifieke NEAR/3 klacht*) OR (insomni* NEAR/3 sever* NEAR/3 index*) OR (6-item NEAR/6 female NEAR/3 sexual* NEAR/3 function*) OR (5-item NEAR/6 erectile NEAR/3 function*) OR (sexual* NEAR/3 health NEAR/3 inventor* NEAR/3 men) OR (body NEAR/3 image NEAR/3 scal*) OR ((EORTC OR ‘European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer’) NEAR/6 (QLQ OR ‘Quality of Life’) NEAR/6 (PATSAT32 OR BR23 OR BR-23 OR CR-29 OR CR29 OR H&N25 OR HN25 OR HN-25)) OR (Caron NEAR/3 screening NEAR/3 questionnaire*) OR (Jong NEAR/3 Gierveld NEAR/3 loneliness) OR (7-item NEAR/3 dyadis NEAR/3 adjustment*) OR (vragenlijst NEAR/3 gezinskenmerken) OR (job NEAR/3 content* NEAR/3 questionnaire*) OR (vragenlijst NEAR/3 beleving NEAR/3 beoordeling NEAR/3 arbeid) OR (Alcohol NEAR/3 five-shot) OR (perceived NEAR/3 stress NEAR/3 scale*) OR (functional NEAR/3 assessment NEAR/3 cancer NEAR/3 therap* NEAR/3 endocrine) OR (breast NEAR/3 impact NEAR/3 treatment NEAR/3 scale*) OR (breast NEAR/3 reconstruction NEAR/3 satisfaction NEAR/3 questionnair*) OR (breast NEAR/3 cancer NEAR/3 patients NEAR/3 needs NEAR/3 questionnaire*) OR (stoma NEAR/3 quality NEAR/3 life NEAR/3 questionnaire*) OR (shoulder* NEAR/3 disabilit* NEAR/3 questionnaire*) OR ((‘CWS’ OR ‘SPK’ OR ‘FSFI-6’ OR ‘IIEF-5’ OR ‘CARON’ OR ‘JGLS’ OR ‘DAS-7’ OR ‘VGK-SF’ OR ‘JCQ’ OR ‘VBBA’ OR ‘A5S’ OR ‘FACT-ES’ OR ‘BITS’ OR ‘BRECON-31’ OR ‘BR-CNPQ’ OR ‘SDQ’ OR ‘stoma-QoL’) NEAR/3 (assess* OR score* OR scale* OR questionnaire* OR inventor* OR measure*))):ab,ti) AND (neoplasm/exp OR (neoplas* OR cancer* OR oncolog* OR tumor* OR tumour OR carcino*):ab,ti) AND (‘validation study’/de OR ‘reproducibility’/de OR ‘psychometry’/de OR ‘observer variation’/de OR ‘discriminant analysis’/de OR ‘correlation coefficient’/de OR reliability/de OR ‘sensitivity and specificity’/de OR validity/exp OR ‘sensitivity analysis’/de OR ‘internal consistency’/de OR ‘confidence interval’/de OR (psychometr* OR reproducib* OR clinimetr* OR clinometr* OR observer-varia* OR reliab* OR valid* OR coefficient OR interna*-consisten* OR (cronbach* NEAR/3 (alpha OR alphas)) OR (item* NEXT/1 (correlation* OR selection* OR reduction*)) OR agreement OR precision OR imprecision OR precise-value* OR test*-retest* OR (test NEAR/3 retest) OR (reliab* NEAR/3 (test OR retest)) OR stability OR interrater OR inter-rater OR intrarater OR intra-rater OR intertester OR inter-tester OR intratester OR intra-tester OR interobserver OR inter-observer OR intraobserver OR intra-observer OR intertechnician OR inter-technician OR intratechnician OR intra-technician OR interexaminer OR inter-examiner OR intraexaminer OR intra-examiner OR interassay OR inter-assay OR intraassay OR intra-assay OR interindividual OR inter-individual OR intraindividual OR intra-individual OR interparticipant OR inter-participant OR intraparticipant OR intra-participant OR kappa OR kappa-s OR kappas OR (coefficient* NEAR/3 variation*) OR repeatab* OR ((replicab* OR repeat*) NEAR/3 (measure OR measures OR findings OR result OR results OR test OR tests)) OR generaliza* OR generalisa* OR concordance OR (intraclass NEAR/3 correlation*) OR discriminative OR ‘known group’ OR (factor* NEAR/3 (analys* OR structure*)) OR dimensionality OR subscale* OR (multitrait NEAR/3 scaling) OR item-discriminant* OR (interscale NEAR/3 correlat*) OR ((error OR errors) NEAR/3 (measure* OR correlat* OR evaluat* OR accuracy OR accurate OR precision OR mean)) OR ((individual OR interval OR rate OR analy*) NEAR/3 variabilit*) OR (uncertaint* NEAR/3 (measure*)) OR (error NEAR/3 measure*) OR sensitiv* OR responsive* OR (limit NEAR/3 detection) OR (minimal* NEAR/3 detectab*) OR interpretab* OR (small* NEAR/3 (real OR detectable) NEAR/3 (change OR difference)) OR (meaningful* NEAR/3 change*) OR (minimal* NEAR/3 (important OR detectab* OR real) NEAR/3 (change* OR difference)) OR ((ceiling OR floor) NEXT/1 effect*) OR ‘Item response model’ OR IRT OR Rasch OR ‘Differential item functioning’ OR DIF OR ‘computer adaptive testing’ OR ‘item bank’ OR ‘cross-cultural equivalence’ OR (confidence* NEAR/3 interval*)):ab,ti)

Medline Ovid

(((cancer ADJ3 worr* ADJ3 scale*) OR (patient ADJ3 specifieke ADJ3 klacht*) OR (insomni* ADJ3 sever* ADJ3 index*) OR (6-item ADJ6 female ADJ3 sexual* ADJ3 function*) OR (5-item ADJ6 erectile ADJ3 function*) OR (sexual* ADJ3 health ADJ3 inventor* ADJ3 men) OR (body ADJ3 image ADJ3 scal*) OR ((EORTC OR “European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer”) ADJ6 (QLQ OR “Quality of Life”) ADJ6 (PATSAT32 OR BR23 OR BR-23 OR CR-29 OR CR29 OR H&N25 OR HN25 OR HN-25)) OR (Caron ADJ3 screening ADJ3 questionnaire*) OR (Jong ADJ3 Gierveld ADJ3 loneliness) OR (7-item ADJ3 dyadis ADJ3 adjustment*) OR (vragenlijst ADJ3 gezinskenmerken) OR (job ADJ3 content* ADJ3 questionnaire*) OR (vragenlijst ADJ3 beleving ADJ3 beoordeling ADJ3 arbeid) OR (Alcohol ADJ3 five-shot) OR (perceived ADJ3 stress ADJ3 scale*) OR (functional ADJ3 assessment ADJ3 cancer ADJ3 therap* ADJ3 endocrine) OR (breast ADJ3 impact ADJ3 treatment ADJ3 scale*) OR (breast ADJ3 reconstruction ADJ3 satisfaction ADJ3 questionnair*) OR (breast ADJ3 cancer ADJ3 patients ADJ3 needs ADJ3 questionnaire*) OR (stoma ADJ3 quality ADJ3 life ADJ3 questionnaire*) OR (shoulder* ADJ3 disabilit* ADJ3 questionnaire*) OR ((“CWS” OR “SPK” OR “FSFI-6” OR “IIEF-5” OR “CARON” OR “JGLS” OR “DAS-7” OR “VGK-SF” OR “JCQ” OR “VBBA” OR “A5S” OR “FACT-ES” OR “BITS” OR “BRECON-31” OR “BR-CNPQ” OR “SDQ” OR “stoma-QoL”) ADJ3 (assess* OR score* OR scale* OR questionnaire* OR inventor* OR measure*))).ab,ti.) AND (neoplasm/ OR (neoplas* OR cancer* OR oncolog* OR tumor* OR tumour OR carcino*).ab,ti.) AND (exp “Validation Studies”/ OR exp “reproducibility of results”/ OR exp “psychometrics”/ OR exp “observer variation”/ OR exp “discriminant analysis”/ OR exp “Sensitivity and Specificity”/ OR “Confidence Intervals”/ OR (psychometr* OR reproducib* OR clinimetr* OR clinometr* OR observer-varia* OR reliab* OR valid* OR coefficient OR interna*-consisten* OR (cronbach* ADJ3 (alpha OR alphas)) OR (item* ADJ (correlation* OR selection* OR reduction*)) OR agreement OR precision OR imprecision OR precise-value* OR test*-retest* OR (test ADJ3 retest) OR (reliab* ADJ3 (test OR retest)) OR stability OR interrater OR inter-rater OR intrarater OR intra-rater OR intertester OR inter-tester OR intratester OR intra-tester OR interobserver OR inter-observer OR intraobserver OR intra-observer OR intertechnician OR inter-technician OR intratechnician OR intra-technician OR interexaminer OR inter-examiner OR intraexaminer OR intra-examiner OR interassay OR inter-assay OR intraassay OR intra-assay OR interindividual OR inter-individual OR intraindividual OR intra-individual OR interparticipant OR inter-participant OR intraparticipant OR intra-participant OR kappa OR kappa-s OR kappas OR (coefficient* ADJ3 variation*) OR repeatab* OR ((replicab* OR repeat*) ADJ3 (measure OR measures OR findings OR result OR results OR test OR tests)) OR generaliza* OR generalisa* OR concordance OR (intraclass ADJ3 correlation*) OR discriminative OR “known group” OR (factor* ADJ3 (analys* OR structure*)) OR dimensionality OR subscale* OR (multitrait ADJ3 scaling) OR item-discriminant* OR (interscale ADJ3 correlat*) OR ((error OR errors) ADJ3 (measure* OR correlat* OR evaluat* OR accuracy OR accurate OR precision OR mean)) OR ((individual OR interval OR rate OR analy*) ADJ3 variabilit*) OR (uncertaint* ADJ3 (measure*)) OR (error ADJ3 measure*) OR sensitiv* OR responsive* OR (limit ADJ3 detection) OR (minimal* ADJ3 detectab*) OR interpretab* OR (small* ADJ3 (real OR detectable) ADJ3 (change OR difference)) OR (meaningful* ADJ3 change*) OR (minimal* ADJ3 (important OR detectab* OR real) ADJ3 (change* OR difference)) OR ((ceiling OR floor) ADJ effect*) OR “Item response model” OR IRT OR Rasch OR “Differential item functioning” OR DIF OR “computer adaptive testing” OR “item bank” OR “cross-cultural equivalence” OR (confidence* ADJ3 interval*)).ab,ti.)

PsycINFO Ovid

(((cancer ADJ3 worr* ADJ3 scale*) OR (patient ADJ3 specifieke ADJ3 klacht*) OR (insomni* ADJ3 sever* ADJ3 index*) OR (6-item ADJ6 female ADJ3 sexual* ADJ3 function*) OR (5-item ADJ6 erectile ADJ3 function*) OR (sexual* ADJ3 health ADJ3 inventor* ADJ3 men) OR (body ADJ3 image ADJ3 scal*) OR ((EORTC OR “European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer”) ADJ6 (QLQ OR “Quality of Life”) ADJ6 (PATSAT32 OR BR23 OR BR-23 OR CR-29 OR CR29 OR H&N25 OR HN25 OR HN-25)) OR (Caron ADJ3 screening ADJ3 questionnaire*) OR (Jong ADJ3 Gierveld ADJ3 loneliness) OR (7-item ADJ3 dyadis ADJ3 adjustment*) OR (vragenlijst ADJ3 gezinskenmerken) OR (job ADJ3 content* ADJ3 questionnaire*) OR (vragenlijst ADJ3 beleving ADJ3 beoordeling ADJ3 arbeid) OR (Alcohol ADJ3 five-shot) OR (perceived ADJ3 stress ADJ3 scale*) OR (functional ADJ3 assessment ADJ3 cancer ADJ3 therap* ADJ3 endocrine) OR (breast ADJ3 impact ADJ3 treatment ADJ3 scale*) OR (breast ADJ3 reconstruction ADJ3 satisfaction ADJ3 questionnair*) OR (breast ADJ3 cancer ADJ3 patients ADJ3 needs ADJ3 questionnaire*) OR (stoma ADJ3 quality ADJ3 life ADJ3 questionnaire*) OR (shoulder* ADJ3 disabilit* ADJ3 questionnaire*) OR ((“CWS” OR “SPK” OR “FSFI-6” OR “IIEF-5” OR “CARON” OR “JGLS” OR “DAS-7” OR “VGK-SF” OR “JCQ” OR “VBBA” OR “A5S” OR “FACT-ES” OR “BITS” OR “BRECON-31” OR “BR-CNPQ” OR “SDQ” OR “stoma-QoL”) ADJ3 (assess* OR score* OR scale* OR questionnaire* OR inventor* OR measure*))).ab,ti.) AND (neoplasm/ OR (neoplas* OR cancer* OR oncolog* OR tumor* OR tumour OR carcino*).ab,ti.) AND (exp “Test Validity”/ OR exp “Test Reliability”/ OR exp “psychometrics”/ OR exp “Interrater Reliability”/ OR exp OR (psychometr* OR reproducib* OR clinimetr* OR clinometr* OR observer-varia* OR reliab* OR valid* OR coefficient OR interna*-consisten* OR (cronbach* ADJ3 (alpha OR alphas)) OR (item* ADJ (correlation* OR selection* OR reduction*)) OR agreement OR precision OR imprecision OR precise-value* OR test*-retest* OR (test ADJ3 retest) OR (reliab* ADJ3 (test OR retest)) OR stability OR interrater OR inter-rater OR intrarater OR intra-rater OR intertester OR inter-tester OR intratester OR intra-tester OR interobserver OR inter-observer OR intraobserver OR intra-observer OR intertechnician OR inter-technician OR intratechnician OR intra-technician OR interexaminer OR inter-examiner OR intraexaminer OR intra-examiner OR interassay OR inter-assay OR intraassay OR intra-assay OR interindividual OR inter-individual OR intraindividual OR intra-individual OR interparticipant OR inter-participant OR intraparticipant OR intra-participant OR kappa OR kappa-s OR kappas OR (coefficient* ADJ3 variation*) OR repeatab* OR ((replicab* OR repeat*) ADJ3 (measure OR measures OR findings OR result OR results OR test OR tests)) OR generaliza* OR generalisa* OR concordance OR (intraclass ADJ3 correlation*) OR discriminative OR “known group” OR (factor* ADJ3 (analys* OR structure*)) OR dimensionality OR subscale* OR (multitrait ADJ3 scaling) OR item-discriminant* OR (interscale ADJ3 correlat*) OR ((error OR errors) ADJ3 (measure* OR correlat* OR evaluat* OR accuracy OR accurate OR precision OR mean)) OR ((individual OR interval OR rate OR analy*) ADJ3 variabilit*) OR (uncertaint* ADJ3 (measure*)) OR (error ADJ3 measure*) OR sensitiv* OR responsive* OR (limit ADJ3 detection) OR (minimal* ADJ3 detectab*) OR interpretab* OR (small* ADJ3 (real OR detectable) ADJ3 (change OR difference)) OR (meaningful* ADJ3 change*) OR (minimal* ADJ3 (important OR detectab* OR real) ADJ3 (change* OR difference)) OR ((ceiling OR floor) ADJ effect*) OR “Item response model” OR IRT OR Rasch OR “Differential item functioning” OR DIF OR “computer adaptive testing” OR “item bank” OR “cross-cultural equivalence” OR (confidence* ADJ3 interval*)).ab,ti.)

Web of science

TS = ((((cancer NEAR/3 worr* NEAR/3 scale*) OR (patient NEAR/3 specifieke NEAR/3 klacht*) OR (insomni* NEAR/3 sever* NEAR/3 index*) OR (6-item NEAR/6 female NEAR/3 sexual* NEAR/3 function*) OR (5-item NEAR/6 erectile NEAR/3 function*) OR (sexual* NEAR/3 health NEAR/3 inventor* NEAR/3 men) OR (body NEAR/3 image NEAR/3 scal*) OR ((EORTC OR “European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer”) NEAR/6 (QLQ OR “Quality of Life”) NEAR/6 (PATSAT32 OR BR23 OR BR-23 OR CR-29 OR CR29 OR H&N25 OR HN25 OR HN-25)) OR (Caron NEAR/3 screening NEAR/3 questionnaire*) OR (Jong NEAR/3 Gierveld NEAR/3 loneliness) OR (7-item NEAR/3 dyadis NEAR/3 adjustment*) OR (vragenlijst NEAR/3 gezinskenmerken) OR (job NEAR/3 content* NEAR/3 questionnaire*) OR (vragenlijst NEAR/3 beleving NEAR/3 beoordeling NEAR/3 arbeid) OR (Alcohol NEAR/3 five-shot) OR (perceived NEAR/3 stress NEAR/3 scale*) OR (functional NEAR/3 assessment NEAR/3 cancer NEAR/3 therap* NEAR/3 endocrine) OR (breast NEAR/3 impact NEAR/3 treatment NEAR/3 scale*) OR (breast NEAR/3 reconstruction NEAR/3 satisfaction NEAR/3 questionnair*) OR (breast NEAR/3 cancer NEAR/3 patients NEAR/3 needs NEAR/3 questionnaire*) OR (stoma NEAR/3 quality NEAR/3 life NEAR/3 questionnaire*) OR (shoulder* NEAR/3 disabilit* NEAR/3 questionnaire*) OR ((“CWS” OR “SPK” OR “FSFI-6” OR “IIEF-5” OR “CARON” OR “JGLS” OR “DAS-7” OR “VGK-SF” OR “JCQ” OR “VBBA” OR “A5S” OR “FACT-ES” OR “BITS” OR “BRECON-31” OR “BR-CNPQ” OR “SDQ” OR “stoma-QoL”) NEAR/3 (assess* OR score* OR scale* OR questionnaire* OR inventor* OR measure*)))) AND (neoplasm/exp OR (neoplas* OR cancer* OR oncolog* OR tumor* OR tumour OR carcino*)) AND ((psychometr* OR reproducib* OR clinimetr* OR clinometr* OR observer-varia* OR reliab* OR valid* OR coefficient OR interna*-consisten* OR (cronbach* NEAR/3 (alpha OR alphas)) OR (item* NEAR/1 (correlation* OR selection* OR reduction*)) OR agreement OR precision OR imprecision OR precise-value* OR test*-retest* OR (test NEAR/3 retest) OR (reliab* NEAR/3 (test OR retest)) OR stability OR interrater OR inter-rater OR intrarater OR intra-rater OR intertester OR inter-tester OR intratester OR intra-tester OR interobserver OR inter-observer OR intraobserver OR intra-observer OR intertechnician OR inter-technician OR intratechnician OR intra-technician OR interexaminer OR inter-examiner OR intraexaminer OR intra-examiner OR interassay OR inter-assay OR intraassay OR intra-assay OR interindividual OR inter-individual OR intraindividual OR intra-individual OR interparticipant OR inter-participant OR intraparticipant OR intra-participant OR kappa OR kappa-s OR kappas OR (coefficient* NEAR/3 variation*) OR repeatab* OR ((replicab* OR repeat*) NEAR/3 (measure OR measures OR findings OR result OR results OR test OR tests)) OR generaliza* OR generalisa* OR concordance OR (intraclass NEAR/3 correlation*) OR discriminative OR “known group” OR (factor* NEAR/3 (analys* OR structure*)) OR dimensionality OR subscale* OR (multitrait NEAR/3 scaling) OR item-discriminant* OR (interscale NEAR/3 correlat*) OR ((error OR errors) NEAR/3 (measure* OR correlat* OR evaluat* OR accuracy OR accurate OR precision OR mean)) OR ((individual OR interval OR rate OR analy*) NEAR/3 variabilit*) OR (uncertaint* NEAR/3 (measure*)) OR (error NEAR/3 measure*) OR sensitiv* OR responsive* OR (limit NEAR/3 detection) OR (minimal* NEAR/3 detectab*) OR interpretab* OR (small* NEAR/3 (real OR detectable) NEAR/3 (change OR difference)) OR (meaningful* NEAR/3 change*) OR (minimal* NEAR/3 (important OR detectab* OR real) NEAR/3 (change* OR difference)) OR ((ceiling OR floor) NEAR/1 effect*) OR “Item response model” OR IRT OR Rasch OR “Differential item functioning” OR DIF OR “computer adaptive testing” OR “item bank” OR “cross-cultural equivalence” OR (confidence* NEAR/3 interval*))))

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Hout, A., Neijenhuijs, K.I., Jansen, F. et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer patients: systematic review of measurement properties of the EORTC QLQ-CR29. Support Care Cancer 27, 2395–2412 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04764-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04764-7