Abstract

Purpose

The current study determined the prevalence of severe fatigue in adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients (aged 18–35 years at diagnosis) consulting a multidisciplinary AYA team in comparison with gender- and age-matched population-based controls. In addition, impact of severe fatigue on quality of life and correlates of fatigue severity were examined.

Methods

AYAs with cancer (n = 83) completed questionnaires including the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS-fatigue), Quality of Life (QoL)-Cancer Survivor, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (reflecting psychological distress), and the Cancer Worry Scale (reflecting fear of cancer recurrence or progression).

Results

The vast majority of participants had been treated with chemotherapy (87%) and had no active treatment at the time of participation (73.5%). Prevalence of severe fatigue (CIS-fatigue score ≥35) in AYAs with cancer (48%, n = 40/83) was significantly higher in comparison with matched population-based controls (20%, n = 49/249; p < .001). Severely fatigued AYAs with cancer reported lower QoL compared to non-severely fatigued AYAs with cancer (p < .05). Female gender, being unemployed, higher disease stage (III–IV) at diagnosis, receiving active treatment at the time of study participation, being treated with palliative intent, having had radiotherapy, higher fear of recurrence or progression, and higher psychological distress were significantly correlated with fatigue severity (p < .05).

Conclusions

Severe fatigue based on a validated cut-off score was highly prevalent in this group of AYAs with cancer. QoL is significantly affected by severe fatigue, stressing the importance of detection and management of this symptom in those patients affected by a life-changing diagnosis of cancer in late adolescence or young adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Compared to adults, a diagnosis of cancer in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) between the ages of 18 and 35 years is rare. Advances in early detection and improvements in cancer treatments have resulted in an overall 5-year survival rate exceeding 80% in AYAs [1]. While AYAs with cancer face challenges similar to adult cancer patients, those in the heart of their youth experience unique cancer-related challenges in addition to usual age-related developmental tasks. The combination of achieving normal developmental milestones and simultaneously coping with a life-changing diagnosis of cancer frequently leads to psychosocial issues among AYAs with cancer [2]. Several studies have documented higher levels of distress and lower quality of life (QoL) in AYAs with cancer in comparison with healthy matched peers or adult cancer patients [3,4,5]. Moreover, treatment-related symptoms (e.g., pain and fatigue) and late effects (e.g., second cancers and cardiovascular disease) can interfere with a healthy body image, establishing social relationships, or attaining levels of autonomy and independence. With the expected further gains in overall survival of AYA cancer, it is important to address persistent disease- and treatment-related symptoms that compromise several domains of QoL.

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is one of the most common and distressing symptoms reported by adult and childhood cancer patients both during and after cancer treatment [6, 7]. The most commonly used definition for CRF is formulated by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and defines CRF as “a distressing, persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness or exhaustion related to cancer or cancer treatment that is not proportional to recent activity that interferes with usual functioning” [8]. The vast majority of studies on the prevalence and severity of CRF have been conducted in adult or childhood cancer patients and only a few studies evaluated fatigue severity in AYAs with cancer. Moreover, the limited AYA-specific studies did not attempt to report on clinically relevant levels of fatigue by using a validated cut-off for severe fatigue [4, 9].

Knowledge on the prevalence of severe fatigue in AYAs with cancer is important, as we know from studies in adult cancer patients that severe fatigue is associated with more functional impairments, lower QoL, and more distress [6, 10]. For AYAs with cancer, the impact of severe fatigue might be even more pronounced because it can interrupt developmental milestones such as completing education, finding first or pursuing employment, beginning a romantic relationship, or starting a family. Understanding factors related to severe fatigue among AYAs with cancer will help health care providers identify who is more likely to experience this symptom. In addition, it will help researchers to determine potential factors that could be addressed in interventions targeting fatigue.

The present study determined the prevalence of clinically relevant levels of fatigue in AYAs with cancer using a validated cut-off for severe fatigue and compared the proportion of severely fatigued cases with the proportion of severely fatigued cases in a sample of gender- and age-matched population-based controls. In addition, the impact of severe fatigue on QoL and potential sociodemographic, treatment-related, and psychological correlates of fatigue severity was explored. A cross-sectional approach was used for this study to gather descriptive information about the presence of clinically relevant levels of fatigue among AYAs with cancer.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients aged 18–35 years at cancer diagnosis and who had been seen by at least one of the members of the AYA team of the Radboud university medical center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, were invited to participate in this study. The AYA team is a dedicated multidisciplinary team including a medical oncologist, clinical nurse specialist, medical psychologist, and social worker. Patients consulting the AYA team receive regular medical care from their own treating specialist (oncologist, surgeon, hematologist, dermatologist, urologist, gynecologist, etc.) and visit the AYA team for age-specific questions and care needs. In general, patients visiting the AYA team represent a group of patients with higher disease severity, diagnosed with relatively advanced stage of disease and undergoing intensive treatments, and reporting more problems with coping. The AYA team does not often see patients with low-stage disease treated solely by surgery, such as in the case of thin melanomas.

To depict the real-life heterogeneous sample of AYAs with cancer visiting the AYA team, AYAs with cancer were included in this first study on the prevalence of severe fatigue regardless of treatment status (during or after treatment), type of treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, hormonal therapy or combination), or the number of AYA team visits (some patients only had one introduction talk with one of the members of the team and did not receive specific care thereafter). Inclusion commenced January 2012 and ended March 2016.

Population-based controls

Population-based controls were derived from a cohort of panel members surveyed by CentERdata, a research institute at Tilburg University collecting data from a sample of more than 2000 Dutch households (https://www.centerdata.nl/en/). This CentERpanel represents the adult Dutch-speaking population with respect to demographic characteristics. Population-based controls provided self-reported data on age and gender and completed a multi-dimensional fatigue questionnaire (Checklist Individual Strength, see “Measures” section). They had no sickness absence in the workplace (0 days) in the month prior to filling in the questionnaires. Further information on the presence of physical or mental health conditions in population-based controls was not available.

Procedure

Potential study participants were recruited via letters describing the study and inviting patients to participate in the study. Patients willing to participate had to actively opt in to the study by providing written informed consent by email to a member of the AYA team. Participants were then sent a single set of questionnaires by email that could be completed online. The study was deemed exempted from full review and approval by a research ethics committee (CMO Regio Arnhem-Nijmegen, #2016-2872).

Measures

AYAs with cancer completed a self-report questionnaire on sociodemographic data (i.e., age, gender, partner status, having children, education level, and employment status). A member of the AYA team (S.K.) extracted clinical data (i.e., cancer diagnosis, disease stage at diagnosis, time since initial cancer diagnosis, type(s) of treatment(s) received, duration of cancer treatment, treatment status at participation, and time since completion of cancer treatment) from patients’ medical records. AYAs with cancer completed the following questionnaires, including a multi-dimensional fatigue questionnaire:

Checklist Individual Strength, subscale fatigue severity (CIS-fatigue)

The subscale fatigue severity of the CIS consists of eight items scored on a seven-point Likert scale. Total CIS-fatigue scores can range from 8 to 56, with scores greater than 34 indicating clinically relevant levels of fatigue [11]. The CIS-fatigue has been used in previous studies examining severe fatigue in cancer patients during and after cancer treatment [12,13,14]. A cut-off was used to group AYAs with cancer into two groups to indicate severely fatigued (≥35) and non-severely fatigued patients (<35).

Quality of Life-Cancer Survivor (QoL-CS)

The QoL-CS consists of 41 items scored on a 10-point Likert scale and was used as a cancer-specific measure of QoL [15]. The impact of cancer diagnosis and treatment is assessed with four subscales, i.e., physical, social, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing. In addition to the four subscale scores, the total QoL score reflecting the average across all items was used in this study. Higher scores indicated better QoL for all subscales.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

The HADS consists of 14 items scored on a four-point Likert scale [16]. The summed total HADS scores range from 0 to 42 and were used to reflect psychological distress in our sample of AYAs with cancer [17]. Higher total scores indicate more psychological distress.

Cancer Worry Scale (CWS)

The CWS consists of eight items regarding concerns about cancer recurrence or progression of cancer. Items are scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “almost always” [18]. Total CWS scores range from 8 to 32 and can be used to assess cancer worrying. Higher total scores indicate more fear of cancer recurrence or progression. Patients with a recent recurrence (n = 5) or receiving treatment with palliative intent (n = 7) did not complete the CWS because the item wording of this measure was irrelevant to them.

Statistical analyses

To compare mean fatigue severity and the prevalence of severe fatigue in AYAs with cancer with population-based controls derived from the sample of CentERdata (n = 1923), AYAs with cancer were matched on gender and age (within a range of 0 to 5 years) with 249 population-based controls. Given the relatively low proportion of CentERpanel members within the age range of our study sample, the highest possible ratio for matching AYAs with cancer to controls was 1:3. Precision matching was performed with STATA/SE. All other analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version 22.0). Descriptive statistics and frequencies concerning socio-demographic and clinical data were calculated. An independent sample t test was used to compare fatigue severity scores between AYAs with cancer and matched population-based controls. We used a chi-square test to compare the proportion of severely fatigued cases in AYAs with cancer and matched population-based controls. Pearson and point-biserial correlations were calculated to examine associations between continuous variables or continuous and dichotomous variables, respectively. The significance level was set at .05. We did not adjust for multiple testing.

Results

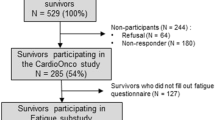

In total, 309 letters requesting participation in the study were sent to AYAs with cancer visiting one of the members of the AYA team. The total sample of 89 participants comprised 57% of those who opted in to the study (n = 155) and 29% of all those solicited by mail (n = 309). Six participants were excluded, four since they were diagnosed with cancer under the age of 18 years and two because they were aged above 35 years at diagnosis. Table 1 displays sociodemographic and disease- and treatment-related characteristics of the final sample of 83 AYAs with cancer stratified by the presence of severe fatigue. Mean age at cancer diagnosis for the total sample was 27.3 years (SD 4.4) and mean time since cancer diagnosis was 2.1 years (SD 2.6). The most common diagnosis was testicular cancer (34%) followed by sarcoma (19%). Disease stage at diagnosis was known and applicable in 67 participants. Of those, 36 (54%) were diagnosed with early stage disease (stages I–II) and 31 (46%) with late-stage disease (stages III–IV). The majority of participants had undergone surgery (n = 70, 84%) and chemotherapy (n = 72, 87%) but were not on active cancer treatment at the time of study participation (n = 61, 73.5%). Mean duration of cancer treatment was 15.8 months (SD 20.6). For the subset of 61 patients not on active cancer treatment at the time of study participation, mean duration since completion of treatment was 17.5 months (SD 30.6).

Prevalence of severe fatigue and impact on quality of life

AYAs with cancer reported a significantly higher fatigue severity score than matched population-based controls (31.5, SD 11.8 versus 24.9, SD 10.5, respectively, p < .001). The prevalence of severe fatigue in AYAs with cancer was significantly higher in comparison with matched population-based controls (48%, n = 40/83 versus 20%, n = 49/249, respectively, p < .001). Severely fatigued AYAs with cancer reported significantly lower scores on all four QoL subscales (i.e., physical, social, psychological, and spiritual well-being) and on total QoL, compared to their non-severely fatigued counterparts (p < .05, see Table 2).

Sociodemographic, treatment-related, and psychosocial correlates of fatigue severity

Correlations are listed in Table 3. Higher psychological distress was strongly correlated to fatigue severity (R = .55; p < .001). Female gender, being unemployed (not having a job, sick leave or disablement insurance act), higher disease stage (III–IV) at diagnosis, and higher fear of recurrence or progression were moderate correlates (R‘s 0.30 to 0.50; p < .01). In addition, receiving active treatment at the time of study participation, palliative intent of treatment, and having had radiotherapy were weakly associated with fatigue severity (R‘s 0.10 to 0.30; p < .05). No significant associations were observed between fatigue severity and the other sociodemographic and disease- and treatment-related variables (see Table 3; p > .05).

Discussion

In this study, severe fatigue affected almost half of the AYAs with cancer. The prevalence of severe fatigue in AYAs with cancer was more than twice as high in AYAs with cancer than in gender- and age-matched population-based controls (48 versus 20%). Severe fatigue as assessed with the CIS-fatigue is more prevalent among AYAs with cancer than adult disease-free breast cancer patients 3 years after diagnosis (38%) [19]. The prevalence among AYAs with cancer corresponds more closely with findings from a study performed in adult cancer patients during cancer treatment with palliative intent (47%) [13], which is remarkable given the major difference in prognosis between these two patient groups. In our sample, only a minority of the participants (n = 12, 14.5%) were classified as being treated with palliative intent at the time of participation. Reasons for the high prevalence of severe fatigue in AYAs with cancer have not been studied. One might postulate that, in contrast to adult cancer patients, the higher prevalence of severe fatigue originates from the unique combination of being diagnosed and treated for cancer and the developmental milestones AYAs are confronted with during adolescence and young adulthood.

Alternatively, the higher prevalence of severe fatigue reported by participants in our study could be the result of selection bias. We recruited AYAs with cancer that consulted a multidisciplinary AYA team. The fact that patients consulted a specialized AYA team most likely indicates that these patients had additional disease and/or treatment-related questions or problems, although not all patients had a need for continued and specific care by the AYA team after the first consultation. The percentage of patients having had chemotherapy as part of AYA cancer treatment was high (87%). This further supports the likelihood of selection bias in our sample and might overestimate disease severity of the entire AYA cancer patient population. Nonetheless, we can conclude that within the subset of AYAs with cancer consulting a multidisciplinary AYA team, the prevalence of severe fatigue is substantial.

Significant differences were found in physical, social, psychological, spiritual, and total QoL for severely fatigued AYAs with cancer in comparison with non-severely fatigued patients, which echoes previous studies reporting on the detrimental effects of severe fatigue in adult cancer patients [6, 10]. More psychological distress was a strong correlate of fatigue severity in the present study. In addition, more cancer worrying, female gender, and being unemployed were moderately related to fatigue severity. Geue et al. (2014) studied gender-specific differences in quality of life after AYA cancer and found lower QoL for women than men, including higher levels of fatigue [20]. The finding that more psychological distress and cancer worrying were associated with fatigue severity is in agreement with the impact of fatigue severity on QoL of AYAs with cancer in this study. However, given the cross-sectional design of our study, we cannot draw conclusions on causality. This also limits interpreting the finding that being unemployed was linked to higher fatigue severity, although it may suggest that severely fatigued AYAs with cancer might not be able to find appropriate work. This emphasizes the relevance of further research into this topic.

We only found weak or non-significant links between treatment-related variables and fatigue severity; receiving active treatment at the time of study participation, receiving treatment with palliative intent, and having had radiotherapy were significant but weakly related to fatigue severity. A moderate association was found between late-stage cancer at diagnosis and fatigue severity. In previous studies among adult cancer patients during and after treatment, fatigue appeared to be unrelated to disease-related variables, but the receipt of chemotherapy was associated with fatigue long after treatment [21]. A recently published review among breast cancer survivors after treatment also reported that survivors treated with chemotherapy were at higher risk for developing severe fatigue, as were those survivors with a higher disease stage at diagnosis [22]. As mentioned before, a noteworthy proportion of participants (87%) in our sample had been treated with chemotherapy.

The present study has several limitations. The sample size of our study was relatively small and the low participation rate increases the probability of bias by non-response. Unfortunately, small sample sizes are also seen in other studies in which patients of AYA age are asked to participate [23, 24]. Recruitment for our study took place over a period of 4 years. Additional efforts to increase data collection, such as multiple mailings of questionnaires or follow-up phone calls, were only made in the latter part of the study. Our response rate might have been higher when these efforts were made throughout the entire duration of the study. However, in the AYA HOPE study, fewer than half of the eligible AYAs with cancer responded to questionnaires despite extensive efforts such as multiple mailings, phone calls, and financial incentives [25]. One way to overcome the low response rate in AYA cancer research might be the use of in-person contact and patient-preferred paper-pencil rather than online surveys as recently suggested by Rosenberg et al. [26]. Given the low incidence of cancer in AYAs between the ages of 18 to 35 years, recruitment from multiple institutions in an (inter)national AYA network could also aid the collection of larger samples. This would also increase the ability to generalize findings, which is limited in our study since we recruited patients at a single university medical center. While a broad range of potential correlates of fatigue severity was studied, we cannot rule out the involvement of other potentially relevant factors that have not been examined in this study. For example, sleep problems are strongly correlated with higher levels of fatigue in patients with cancer [27]. In addition, a low level of physical activity and pain are also correlated with cancer-related fatigue [28]. There is evidence that the effect of sleep problems on fatigue is mediated by pain [29]. Unfortunately, we did not include validated instruments to assess sleep problems, physical activity, and pain as potential correlates of fatigue severity in our sample, which is a significant limitation of the study. Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study is the first to apply a clinically relevant cut-off for severe fatigue in AYAs with cancer aged between 18 and 35 years at diagnosis.

In conclusion, given the high prevalence and significant impact of severe fatigue on quality of life of AYAs with cancer, health care providers should pay careful attention to this symptom. In particular, female AYAs with cancer, those with more advanced disease at diagnosis, higher levels of psychological distress, and more cancer worrying seem to experience higher levels of fatigue. The longer-term survivorship rates of AYA cancer illustrate the potential longevity of AYAs with cancer. It is therefore important to investigate the course and persistence of severe fatigue in AYAs with cancer in longitudinal, population-based studies. Such studies would also aid the development of age-specific interventions addressing persistent cancer-related fatigue in AYAs with cancer to enable full participation in society throughout survivorship. Although evidence-based interventions for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adult cancer survivors are available and recommended within guidelines issued by the American Society for Clinical Oncology [30], these interventions have not been tested extensively in AYAs with cancer. Researchers should investigate whether these interventions can also be successfully applied to alleviate persistent cancer-related fatigue, improve QoL, and facilitate participation in society for the understudied population of AYAs with cancer.

Change history

20 June 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

References

Barr RD, Ferrari A, Ries L et al (2016) Cancer in adolescents and young adults: a narrative review of the current status and a view of the future. JAMA Pediatr 170(5):495–501

Zebrack BJ (2011) Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer 117(10 Suppl):2289–2294

Sansom-Daly UM, Wakefield CE (2013) Distress and adjustment among adolescents and young adults with cancer: an empirical and conceptual review. Transl Pediatr 2(4):167–197

Smith AW, Bellizzi KM, Keegan TH et al (2013) Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer in the United States: the adolescent and young adult health outcomes and patient experience study. J Clin Oncol 31(17):2136–2145

Salsman JM, Garcia SF, Yanez B et al (2014) Physical, emotional, and social health differences between posttreatment young adults with cancer and matched healthy controls. Cancer 120(15):2247–2254

Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD et al (2007) Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist 12(Suppl 1):4–10

Tomlinson D, Zupanec S, Jones H et al (2016) The lived experience of fatigue in children and adolescents with cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 24(8):3623–3631

Berger AM, Mooney K, Alvarez-Perez A et al (2015) Cancer-related fatigue, version 2.2015. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 13(8):1012–1039

Aksnes LH, Hall KS, Jebsen N et al (2007) Young survivors of malignant bone tumours in the extremities: a comparative study of quality of life, fatigue and mental distress. Support Care Cancer Sep 15(9):1087–1096

Curt GA, Breitbart W, Cella D et al (2000) Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: new findings from the fatigue coalition. Oncologist 5(5):353–360

Vercoulen JH, Swanink CM, Fennis JF et al (1994) Dimensional assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res 38(5):383–392

Goedendorp MM, Peters ME, Gielissen MF et al (2010) Is increasing physical activity necessary to diminish fatigue during cancer treatment? Comparing cognitive behavior therapy and a brief nursing intervention with usual care in a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Oncologist 15(10):1122–1132

Peters ME, Goedendorp MM, Verhagen CA et al (2014) Severe fatigue during the palliative treatment phase of cancer: an exploratory study. Cancer Nurs 37(2):139–145

Gielissen MF, Verhagen S, Witjes F et al (2006) Effects of cognitive behavior therapy in severely fatigued disease-free cancer patients compared with patients waiting for cognitive behavior therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 24(30):4882–4887

Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M (1995) Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res 4(6):523–531

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiat Scand 67(6):361–370

Vodermaier A, Millman RD (2011) Accuracy of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 19(12):1899–1908

Custers JA, van den Berg SW, van Laarhoven HW et al (2014) The Cancer Worry Scale: detecting fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 37(1):E44–E50

Servaes P, Verhagen S, Bleijenberg G (2002) Determinants of chronic fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. Ann Oncol 13(4):589–598

Geue K, Sender A, Schmidt R et al (2014) Gender-specific quality of life after cancer in young adulthood: a comparison with the general population. Qual Life Res 23(4):1377–1386

Servaes P, Verhagen C, Bleijenberg G (2002) Fatigue in cancer patients during and after treatment: prevalence, correlates and interventions. Eur J Cancer 38(1):27–43

Abrahams HJ, Gielissen MF, Schmits IC et al (2016) Risk factors, prevalence, and course of severe fatigue after breast cancer treatment: a meta-analysis involving 12 327 breast cancer survivors. Ann Oncol 27(6):965–974

Hall AE, Boyes AW, Bowman J et al (2012) Young adult cancer survivors' psychosocial well-being: a cross-sectional study assessing quality of life, unmet needs, and health behaviors. Support Care Cancer 20(6):1333–1341

Larsson G, Mattsson E, von Essen L (2010) Aspects of quality of life, anxiety, and depression among persons diagnosed with cancer during adolescence: a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Cancer 46(6):1062–1068

Harlan LC, Lynch CF, Keegan TH et al (2011) Recruitment and follow-up of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: the AYA HOPE study. J Cancer Surviv 5:305–314

Rosenberg AR, Bona K, Wharton CM et al (2016) Adolescent and young adult patient engagement and participation in survey-based research: a report from the “Resilience in Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer” study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63(4):734–736

Roscoe JA, Kaufman ME, Matteson-Rusby SE et al (2007) Cancer-related fatigue and sleep disorders. Oncologist 12(Suppl 1):35–42

Wagner LI, Cella D (2004) Fatigue and cancer: causes, prevalence and treatment approaches. Br J Cancer 91:822–828

Stepanski EJ, Walker MS, Schwartzberg LS et al (2009) The relation of trouble sleeping, depressed mood, pain, and fatigue in patients with cancer. J Clin Sleep Med 5(2):132–136

Bower JE, Bak K, Berger A et al (2014) Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: an American Society of Clinical oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol 32(17):1840–1850

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating AYAs with cancer, Lotte Bloot for preparing the data of the matched population-based controls, and Marianne Heins for helping with the matching procedure.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society under Grant number KUN2011-5259.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised: Tables 2 and 3 are corrected.

An erratum to this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3778-5.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Poort, H., Kaal, S.E.J., Knoop, H. et al. Prevalence and impact of severe fatigue in adolescent and young adult cancer patients in comparison with population-based controls. Support Care Cancer 25, 2911–2918 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3746-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3746-0