Abstract

Purpose

Glioma patients and their informal caregivers face many challenges in living with the disease and its disease-specific consequences. To better meet their needs, a system to monitor symptoms, distress, and quality of life could prove useful. We explored glioma patients’ and caregivers’ attitudes and preferences toward monitoring in general and specifically toward paper-and-pencil and computerized (eHealth) options.

Methods

In total, 15 patients and 15 informal caregivers participated in individual, semi-structured interviews. Interviews were transcribed smooth verbatim and coded by two researchers independently.

Results

Advantages of monitoring generated by participants include increased awareness of problems and their flow over time, and facilitating supportive care provision. Disadvantages include investment of time and mastering the discipline to monitor frequently. Patients reported more disadvantages of monitoring, including practical and disease-specific impediments, while caregivers mentioned more advantages. Preferences for specific methods mentioned to monitor are highly personal but most prefer to have an option for face-to-face contact to discuss results of monitoring with health care professionals even in computerized instruments.

Conclusions

Informal caregivers view a monitoring system more favorably than glioma patients. In developing an efficient monitoring system to help glioma patients and caregivers find their way to supportive care, a computerized instrument with the added opportunity to contact a health care professional seems to be the best option to advise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Gliomas, the most common primary malignant brain tumors, can have a devastating impact on the lives of both patients and those close to them. These tumors lead to neurological symptoms that can cause a disease burden distinctly different from other cancer patients [1]. For example, paresis, visual-perceptual deficits, sensory loss, cognitive deficits, and seizures are common [2], and changes in personality and behavior can occur [3, 4].

As the disease progresses, symptoms may become more pronounced and patients have to rely more on their informal caregivers. Consequently, many informal caregivers experience considerable caregiver burden [5, 6], and psychological distress is reported in approximately half of all family caregivers [7]. Various studies have explored the needs of both patients and informal caregivers related to information disclosure and communication, service provision, and supportive care options [8]. Meeting the needs of patients and informal caregivers may reduce their symptoms and psychological distress and improve their quality of life (QOL). Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) might help identify symptoms and distress, track changes over time, and could serve as an indicator of relevant topics to discuss [9]. Particularly, monitoring over time in combination with feedback is suggested to provide better insight into problems that patients and caregivers encounter, and to facilitate referral to appropriate supportive care options [10].

Few studies have focused on using monitoring instruments in brain tumor patients [11–16]. Monitoring for QOL issues [11], disease-specific issues [16], and distress and depression [14] was found feasible in neuro-oncology patients in clinical practice. However, none of these studies has included informal caregivers reporting on their own problems. Moreover, in only two studies [14, 16], the focus was on instruments reporting results to patients themselves instead of to physicians.

Monitoring can be conducted in several ways: by means of paper-and-pencil instruments and by means of computerized or Web-based (eHealth) applications. It is expected that eHealth applications could prove to be useful tools in implementing monitoring in the health care system, because of 24/7 availability, and report in real-time instead of retrospectively [17]. In introducing such innovations into clinical practice, it is important to actively engage the end users (i.e., patients and caregivers) in order to improve the effectiveness and uptake [18, 19].

Therefore, the present study aimed at examining the perspective of glioma patients and informal caregivers on monitoring their own symptoms, distress, and QOL. Our research objectives were to discover (1) if glioma patients and informal caregivers are interested in monitoring their own symptoms, psychological distress, and QOL in clinical practice; and (2) what the attitudes and preferences of glioma patients and informal caregivers are toward paper-and-pencil instruments and eHealth applications, and toward face-to-face and automated feedback. Based on study results, suggestions for an efficient way to provide glioma patients and caregivers with the means of reporting their concerns and obtaining appropriate supportive care (e.g., symptom management interventions, physical therapy or psychological support, or more informal supportive care such as peer support groups) are provided.

Methods

Sample and procedure

Adult glioma patients and informal caregivers of glioma patients were recruited at the outpatient department of the VU University Medical Center in Amsterdam. Patients were eligible if they (1) were >18 years of age and (2) were diagnosed with a histologically confirmed WHO grade II, III, or IV glioma. Caregivers were eligible if they (1) were >18 years of age and (2) were the primary informal caregiver of a patient with histologically confirmed WHO II, III, or IV glioma. Neither patients nor caregivers could participate if they did not speak Dutch. We employed purposive sampling to obtain a varied sample with regard to diagnoses and disease stages.

The nurse practitioner or treating physician introduced potential participants to the study by handing out an information letter. With permission from the potential participants, a member of the research team (FWB or KH) contacted them to ask if they were willing to participate. The semi-structured interviews, taking approximately 60 min, were scheduled either at the hospital or at a location of the participant’s preference. All participants were interviewed individually. Interviews were performed until data saturation was obtained in the patient and caregiver interviews separately, meaning that the last interview(s) generated no new information [20]. All interviews were audiotaped. Information on disease and treatment was extracted from the medical records. All participants signed written, informed consent forms and the study was approved after expedited review by the Institutional Review Board of the VU University Medical Center (protocol number 13/309).

Interviews

All interviews (N = 30) were performed by one member of the research team (KH). A semi-structured interview schedule was used (see Table 1). Interview topics and questions were based on our clinical experience and literature [21–23]. If open-ended questions elicited little response, prompts were offered.

We proposed three methods of monitoring (see the Online Resource for additional information). Participants were presented with a paper-and-pencil screening instrument (the Patient Concerns Inventory [16] (PCI) for patients; the Distress Thermometer [24] (DT) for informal caregivers). Additionally, it was explained that this can be combined with face-to-face feedback and referral if needed. Furthermore, a computer-based monitoring application was presented: Oncoquest [25], a touch screen application available in the outpatient clinic, which can be paired with face-to-face feedback and referral. Finally, an eHealth application was introduced by means of screenshots: Oncokompas [26], an eHealth instrument available from home, which provides instant tailored feedback and referral to personalized supportive care options. Both Oncoquest and Oncokompas comprise QOL measurements. These different instruments were selected because they vary in the degree to which technology is involved.

Data analysis and reporting

The interviews were transcribed smooth verbatim using F4 software [27]. Data analysis was conducted by two coders (WC and FWB) by thematic analysis [28, 29]. Both coders read the transcripts several times to familiarize themselves with the content and highlighted sections of the transcripts that were related to the research objectives and independently selected and coded these into key issues and themes (separately for the patient and caregiver interviews). After every three interviews, the coders discussed their findings, refined the key issues and themes, and resolved possible differences until consensus was reached guided by a third researcher (CvU). Finally, one coder (FWB) examined the raw transcripts again to ensure that the analytical process was robust and to confirm that all data were reflected in the coding. In this paper, the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) [30] were followed. All quotes provided were anonymized and translated to English by a professional translator.

Results

Participants

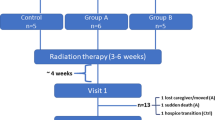

In total, 18 patients received the study information and all were willing to participate (see Fig. 1 for participant flow). Two patients did not show on the scheduled meeting time, and one interview was canceled because data saturation had already occurred. Twenty-four informal caregivers were approached with study information. Six informal caregivers declined to participate: Three caregivers were too busy, two caregivers were too overwhelmed, and one caregiver was gravely ill. In three additional cases, a suitable date for the interview could not be scheduled. Data saturation started after approximately 12 interviews in both patient and caregiver samples, after which an additional three interviews were conducted to ensure that we had indeed reached data saturation. In total, a representative sample of 15 glioma patients and 15 informal caregivers with a wide range of pathologic diagnoses in different disease stages were interviewed (see Table 2 for details). Below, the results that were relevant in terms of the research objectives are described.

Monitoring symptoms, distress, and QOL in clinical practice

Current supportive care provision

Most patients mentioned to be content with the information provided by the hospital, while many informal caregivers felt this did not suffice or was unclear. Patients indicated that because of time constraints and a varying level of interest from physicians, they did not always feel there was enough attention for the person behind the disease:

‘Yes, it just doesn’t feel so… easy and… familiar, so to speak, and you have the feeling that it all has to be done in a hurry, so, I think, yes... never mind.’ (Female glioblastoma patient (42 years), currently under treatment)

With regard to referral to supportive care, patients indicated that although their symptoms were heard, supportive care was often only offered if actively requested. At the same time, both patients and caregivers stated that they were uncertain who their treating physician is. Moreover, informal caregivers mentioned to find it difficult to ask for help for themselves, as they feel the patient should be the center of attention. Patients said to receive several forms of supportive care, e.g., a psychologist, rehabilitation, advance care planning, and spiritual care, while caregivers mostly said to rely on support from those close to them.

Advantages and disadvantages of monitoring

Table 3 lists the advantages and disadvantages of monitoring. An important advantage of monitoring indicated by both patients and caregivers is that it can help you learn more about yourself and that it can create more attention for symptoms or issues and their flow over time. Monitoring was mentioned to facilitate the conversation with the treating physician and, therefore, to be useful in preventing the problems from worsening:

‘That you… that you had better follow things over time, what is happening to you, how you are doing, yes. Well you know, whether your condition has indeed improved or deteriorated, or your weight... or, those kinds of things. That you are triggered to… to take the necessary action if things are not well.’ (Male grade III oligodendroglioma patient (65 years), progressive disease suspected)

Downsides of monitoring were also mentioned. Both patients and caregivers said that it could be difficult to master the discipline to monitor regularly and that it can be time consuming. Furthermore, they feared that it would increase awareness of problems they did not know they had and that it could be difficult to face (worsening) symptoms:

‘But I also have to be careful that I do not go and sit there thinking up things, like, what do I find so hard..’ (Male caregiver (76) of a grade III astrocytoma patient with stable disease)

Participants who experienced no needs considered monitoring to be pointless. However, patients and caregivers did feel that it might be useful for others who do experience needs and are less able to cope with symptoms or distress.

Preferences regarding monitoring

Patients generated mainly physical symptoms as topics to monitor. Cognitive deficits, changes in personality, mood, and emotional reactions were also mentioned. Caregivers mainly mentioned mental symptoms, such as depressive mood and stress. Moreover, changes in the relationship with the patient and in everyday life, and coping with the patient’s symptoms were frequently mentioned. Many topics mentioned by caregivers were associated with grief and acceptance:

‘Also the… amount of time I really spend with my husband, quality time. I have been wondering about… those are also things I wonder about. Like, is this normal what is happening here. What… what do people do when you tell them you only have so and so long to live.’ (Female caregiver (52 years) of a glioblastoma patient with disease progression)

Both patients and caregivers thought receiving feedback on the results of monitoring was essential. They indicated that with feedback, changes over time become apparent, and it can provide more insight into the problems experienced. Patients would like to know if symptoms are normal, considering the circumstances. Several caregivers mentioned that feedback and advice alone could provide solace:

‘Yes, in itself I do believe that it... may give some relief since you know there is care available. Oh dear, not that you, that I would immediately use it, but I, again believe, the idea that you, the sheer knowing that it is there... that could be very comforting.’ (Female caregiver (52 years) of a glioblastoma patient who is under treatment)

Subsequent referral to supportive care was considered useful by most patients and caregivers. Informal caregivers believed that referral after monitoring can save time and effort to seek out help.

Different monitoring instruments

Tables 4, 5 and 6 provide an overview of participants’ thoughts on the different monitoring instruments. Generally, patients felt that any of the presented instruments would be an improvement in existing health care, as it can help guide the discussion with the physician. Some even see its implementation as a form of good “customer service.” Patients had various different opinions on social influence by peers or health care professionals. A few caregivers indicated that recommendation by the treatment team specifically would encourage them to use a monitoring instrument:

‘I take that seriously, yes. Yes, of course. That… you must take it seriously. I do. Of course, it is not something you can simply wave away. I see it as an exam. No, then, yes then I will.’ (Female caregiver (67 years) of a glioblastoma patient with stable disease)

Paper-and-pencil instrument

Patients said the PCI seems to be a simple instrument that would be easy to complete because the different topics are concrete and clear, and believe that it can help recognize problems and initiate discussion (Table 4). As the PCI does not allow for an indication of the severity of symptoms, patients said it only provided a snapshot picture of their concerns, which may hinder its usefulness. Patients indicated that they expected the social cues from face-to-face feedback would help them in the interpretation of the advice provided and would allow them to ask questions.

Informal caregivers felt the DT included relevant topics and could help initiate a conversation about supportive care (Table 4). They expected the DT to be easy to complete. Face-to-face feedback was mentioned to be highly appreciated and could make them feel acknowledged. However, restrictions of the DT mentioned include that some caregivers found it too superficial and that the answer options do not do justice to subtle fluctuations in symptoms or concerns. They indicated that questions were difficult to interpret and that it would be difficult to monitor supportive care needs over time.

Computerized application: Oncoquest

Patients indicated that Oncoquest provides a more detailed description of needs compared to the PCI (Table 5). The option to receive face-to-face feedback was mentioned to be an advantage, although some patients indicated that they would also like to receive feedback in written form:

‘Preferably on paper, but I also say that because of my current… short-term memory.’ (Male grade III oligodendroglioma patient (65 years), progressive disease suspected)

Participants mentioned certain restrictions of Oncoquest, e.g., difficulty of answering multiple-choice questions. Oncoquest’s availability at the outpatient clinic only (and not in the home-situation) could limit the frequency of monitoring, and the timing could be poor as, during a hospital visit, they might receive bad news. Other downsides mentioned were investment of time, money (parking costs), increased fatigue as a result of completing a series of questions, and privacy concerns, as it may be unclear to patients what happens with their data.

Caregivers mentioned more advantages of Oncoquest (Table 5). They indicated to expect that completing Oncoquest would not take long, and the answers go straight to the physician. The availability of the instrument at the outpatient clinic was seen as an advantage by some, as at this time, their focus is already on the disease. Others indicated that completing the questions from home would be better:

‘Well, my first thought is not… not like, then and there. Since, as I have already said, the moments that we go to the hospital are always a little tense... and I… I am more focused on my husband.’ (Female caregiver (52 years) of a glioblastoma patient with disease progression)

Face-to-face feedback was again highly appreciated for similar reasons as mentioned by patients.

eHealth application: Oncokompas

Patients expected Oncokompas to empower the user, increasing knowledge of symptoms or concerns while allowing you to take control of your own needs (Table 6). Caregivers expected Oncokompas to reduce the barrier for exploring supportive care options for themselves. Other advantages mentioned included the instant, tailored advice which could facilitate finding supportive care options, and the trustworthiness of the information provided as it comes from the hospital. Patients and caregivers felt using Oncokompas from their home computer would be convenient, as it would allow them to monitor at a time and frequency of their choosing:

‘I believe yes, that… that would, of course, be very convenient if you could just arrange it through the computer. […]. Then you don’t have to be there at half past ten. […] So yes, that might be even more appealing. Also because you then could do this more often. Without constantly going to and fro.’ (Male grade II oligodendroglioma patient (51 years), stable disease)

Furthermore, patients appreciated being able to take their time to complete questions, as this can take longer in people with language problems. Caregivers especially appreciated the flexible timing, as during hospital visits the focus is usually on the patient and not on them. Patients did stress that Oncokompas should not replace existing health care but rather exist as a supplement.

Patients and caregivers also identified restrictions. With Oncokompas, there is no face-to-face contact with health care professionals, which was experienced as impersonal. Patients furthermore indicated that their privacy should be assured while using the website. They also identified practical difficulties such as undertaking action independently following the advice. A number of patients indicated they are less able to use computers than before, due to loss of strength in their hands, memory problems causing issues with passwords, and fatigue, language, or visual problems:

‘Yes, I am not someone who… who really likes to, as it were, crawl behind my computer and then... that… that actually takes quite a lot of effort nowadays.’ (Male grade IV glioblastoma patient (51 years), currently under treatment)

Both patients and caregivers expected completing the questionnaires online would take a lot of time. Caregivers explicitly mentioned that this would likely result in a low expected use of Oncokompas.

Discussion

This study is the first to evaluate neuro-oncology patients’ and caregivers’ preferences and attitudes regarding a system of monitoring symptoms, distress, and QOL, in order to obtain insight into an efficient way to report symptoms and concerns and to provide them with appropriate supportive care options when needed. First, we evaluated patients’ and caregivers’ issues with the current provision of supportive care. Although in both groups many similar issues were reported, especially caregivers report problems that remain untreated. Caregivers often find it difficult to ask for care for themselves, which is in line with previous studies [4]. This stresses the need to make supportive care options more readily available for caregivers specifically.

To achieve this, a system based on monitoring symptoms, distress, and QOL might be useful. Most glioma patients and caregivers viewed this type of system favorably. Members of our research group have previously investigated the needs of breast cancer and head and neck cancer patients regarding online monitoring [21]. Although many of the more general (dis)advantages generated by those patients are similar, such as enabling one to gain insight into changing symptoms, glioma patients generated additional disease-specific or practical disadvantages. They appear more concerned with the ultimately progressive course of the disease, and cognitive problems that may cause them to need help using this system. Similar difficulties have been found in other eHealth initiatives for glioma patients [31]. Because of these specific difficulties, implementing a monitoring system may be less suitable in this patient population. Indeed, glioma patients’ reactions to both computerized monitoring instruments were mixed. A solution could be to have the patient and caregiver complete the instruments’ questions together—although this would place additional burden on caregivers and may raise privacy issues.

Caregivers generally viewed a monitoring system more favorably than patients. They indicated that it may facilitate the initiation of supportive care when needed, which could be a consequence of their larger proportion of unrecognized and untreated issues. Many patients and caregivers did stress that feedback of the results and referral to supportive care should be an integral part of using a monitoring system in clinical practice, a notion that is supported by Mitchell [10].

When presented with an eHealth application that provides instant tailored feedback and options for referral (Oncokompas), many patients expected difficulty in taking action independently upon receiving automated feedback. Caregivers expected to benefit more from Oncokompas, as this online system can decrease the barrier to contact health care professionals for their own needs. A requirement mentioned by both patients and caregivers was that completing online questions should not take too long, because of a decreased expectancy of use with an increased investment of time. Moreover, both patients and caregivers appreciated additional options for face-to-face feedback. This could be as subtle as adding the option to contact a health care professional in Oncokompas.

This study has some limitations. The study sample is relatively small and comprises a mixed group of low- and high-grade glioma patients and caregivers, possibly limiting the generalizability of our findings. Because we employed a purposive sampling method to ensure that we included participants with a wide range of neuro-oncological diagnoses in different disease stages, any differences between low- and high-grade populations might not show. In addition, there are relatively few patient participants who had recently been diagnosed, and the distribution in male/female participants is a slight exaggeration of the usual distribution seen in glioma patient and caregiver populations (i.e., more male patients and more female caregivers). Some patients displayed evident issues with memory retrieval, difficulty finding words, and diminished mental flexibility during the interviews. The examples of monitoring instruments were presented on paper (e.g., screenshots), which may have made it difficult for some participants to fully understand the functionalities of the instruments. In further development of eHealth monitoring instruments specifically, a usability test with the intended end users is recommended [32].

To summarize, while the preferred method for monitoring remains highly personal, with some preferring online self-management options and others preferring only face-to-face care, the desired way to proceed is likely to combine online and face-to-face care: “blended care.” Developing a computerized form of monitoring with the possibility to contact a health care professional if needed seems to be advised. This, in itself, can raise questions about feasibility and cost-effectiveness which should be addressed in further studies.

Regardless, three general conclusions can be drawn from this study. First, a system of monitoring symptoms, psychological distress, and QOL appears to be viewed more favorably by caregivers than by glioma patients. Second, glioma patients experience disease-specific symptoms that may hinder them in using a monitoring instrument independently. And finally, both patients and caregivers appear to prefer a computerized form of monitoring as long as there is the option to contact a health care professional if needed.

References

Sherwood P, Given B, Given C, Schiffman R, Murman D, Lovely M (2004) Caregivers of persons with a brain tumor: a conceptual model. Nurs Inq 11:43–53

Mukand JA, Blackinton DD, Dilshad D, Croncoli MG, Lee JJ, Santos BB (2001) Incidence of neurologic deficits and rehabilitation of patients with brain tumors. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 80:346–350

MR L (2010) Psychosocial implications for the patient with a high-grade glioma. J Neurosci Nurs 42:104–108 4

Sterckx W, Coolbrandt A, de Casterle BD, Van den Heede K, Decruyenaere M, Borgenon S, Mees A, Clement P (2013) The impact of a high-grade glioma on everyday life: a systematic review from the patient’s and caregiver’s perspective. Eur J Oncol Nurs 17:107–117

Grov EK, Fossa SD, Sorebo O, Dahl AA (2006) Primary caregivers of cancer patients in the palliative phase: a path analysis of variables influencing their burden. Soc Sci Med 63:2429–2439

Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, Clinch J, Reyno L, Earle CC, Willan A, Viola R, Coristine M, Janz T (2004) Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. Can Med Assoc J 170:1795–1801

Choi CW, Stone RA, Kim KH, Ren D, Schulz R, Given CW, Given BA, Sherwood PR (2012) Group-based trajectory modeling of caregiver psychological distress over time. Ann Behav Med 44(1):73–84

Moore G, Collins A, Brand C, Gold M, Lethborg C, Murphy M, Sundararajan V, Philip J (2012) Palliative and supportive care needs of patients with high-grade glioma and their carers: A systematic review of qualitative literature. Patient Educ Couns 91:141–153

Snyder CF, Jensen RE, Geller G, Carducci MA, Wu AW (2010) Relevant content for a patient-reported outcomes questionnaire for use in oncology clinical practice: putting doctors and patients on the same page. Qual Life Res 19:1045–1055

Mitchell AJ (2013) Screening for cancer-related distress: when is implementation successful and when is it unsuccessful? Acta Oncol 52:216–224

Erharter A, Giesinger J, Kemmler G, Schauer-Maurer G, Stockhammer G, Muigg A, Hutterer M, Rumpold G, Sperner-Unterweger B, Holzner B (2010) Implementation of computer-based quality-of-life monitoring in brain tumor outpatients in routine clinical practice. J Pain Symptom Manag 39:219–229

Keir ST, Calhoun-Eagan RD, Swartz JJ, Saleh OA, Friedman HS (2008) Screening for distress in patients with brain cancer using the NCCN’s rapid screening measure. Psycho-Oncology 17:621–625

Kvale EA, Murthy R, Taylor R, Lee JY, Nabors LB (2009) Distress and quality of life in primary high-grade brain tumor patients. Support Care Cancer 17:793–799

Renovanz M, Gutenberg A, Haug M, Strittmatter E, Mazur J, Nadji-Ohl M, Giese A, Hopf N (2013) Postsurgical screening for psychosocial disorders in neurooncological patients. Acta Neurochir 155:2255–2261

Rooney AG, McNamara S, Mackinnon M, Fraser M, Rampling R, Carson A, Grant R (2013) Screening for major depressive disorder in adults with cerebral glioma: an initial validation of 3 self-report instruments. Neuro-Oncology 15:122–129

Rooney AG, Netten A, McNamara S, Erridge S, Peoples S, Whittle I, Hacking B, Grant R (2014) Assessment of a brain-tumour-specific patient concerns inventory in the neuro-oncology clinic. Support Care Cancer 22:1059–1069

Johansen MA, Berntsen GK, Schuster T, Henriksen E, Orsch A (2012) Electronic symptom reporting between patient and provider for improved health care service quality: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Part 2: Methodological quality and effects. J Med Internet Res 14:e126

Nijland N, van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Kelders SM, Brandenburg BJ, Seydel ER (2011) Factors influencing the use of a Web-based application for supporting the self-care of patients with type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. J Med Internet Res 13(3):e71. doi:10.2196/jmir.1603

van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Nijland N, van Limburg M, Ossebaard HC, Kelders SM, Eysenbach G, Seydel ER (2011) A holistic framework to improve the uptake and impact of eHealth technologies. J Med Internet Res 13(4):e111. doi:10.2196/jmir.1672

Francis J, Johnston M, Robertson C, Glidewell L, Entwistle V, Eccles M, Grimshaw J (2015) What is an adequate sample size? operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health 25:1229–1245

Lubberding S, Uden-Kraan CF, Te Velde EA, Cuijpers P, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2015) Improving access to supportive cancer care through an eHealth application: a qualitative needs assessment among cancer survivors. J Clin Nurs 24:1367–1379

Stinson JN, Toomey PC, Stevens BJ, Kagan S, Duffy CM, Huber A, Malleson P, McGrath PJ, Yeung RS, Feldman BM (2008) Asking the experts: exploring the self-management needs of adolescents with arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 59:65–72

Vaart R, Drossaert CHC, Taal E, van de Laar MAFJ (2010) Experiences and preferences of patients with rheumatic diseases regarding an interactive health communication application. Second International Conference on eHealth, Telemedicine, and Social Medicine:64–71, St. Maarten

Zwahlen D, Hagenbuch N, Carley MI, Recklitis CJ, Buchi S (2008) Screening cancer patients’ families with the distress thermometer (DT): a validation study. Psycho-Oncology 17:959–966

Cnossen IC, de Bree R, Rinkel RN, Eerenstein SE, Rietveld DH, Doornaert P, Buter J, Langendijk JA, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2012) Computerized monitoring of patient-reported speech and swallowing problems in head and neck cancer patients in clinical practice. Support Care Cancer 20:2925–2931

Duman-Lubberding S, van Uden-Kraan CF, Peek N, Cuijpers P, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de leeuw IM (2015) An eHealth application in head and neck cancer survivorship care: health care professionals’ perspectives. J Med Internet Res(in press) 17(10):e235. doi:10.2196/jmir.4870

f4transkript (2015) Fast Manual Transcription of Audio and Video www.audiotranskription.de/english/f4.htm. Accessed 8 December 2015

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Joffe H, Yardley L (2004) Content and thematic analysis. Res Methods Clin Health Psychol 56

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19:349–357

Piil K, Jakobsen J, Juhler M, Jarden M (2015) The feasibility of a brain tumour website. Eur J Oncol Nurs 19:686–693

Bastien JC (2010) Usability testing: a review of some methodological and technical aspects of the method. Int J Med Inform 79:e18–e23

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and informal caregivers who participated in this study, as well as nurse practitioners Claudia Nijboer and Alieke Weerdesteijn for helping with recruitment. Finally, many thanks to Heleen Melissant for her contribution in setting up this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No financial support was received for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Boele, F.W., van Uden-Kraan, C.F., Hilverda, K. et al. Attitudes and preferences toward monitoring symptoms, distress, and quality of life in glioma patients and their informal caregivers. Support Care Cancer 24, 3011–3022 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3112-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3112-7