Abstract

Purpose

Current data suggests that potentially inappropriate medicines (PIMs) are common in palliative cancer patients; however, there is a lack of criteria to assist clinicians in identifying PIMs in these patients. The aims of this study were to design and validate a deprescribing guideline for palliative cancer patients and to undertake a descriptive analysis of the identified PIMs.

Methods

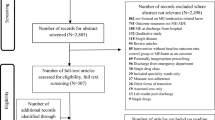

This prospective, non-interventional cohort study consisted of four major stages: developing an ‘OncPal Deprescribing Guideline’ from current evidence, the prospective recruitment of consecutive palliative cancer inpatients with an estimated <6-month prognosis, the assessment of all medications to identify PIMs using both a panel of medical experts without access to the guideline as well as a Clinical Pharmacist independently using the OncPal Deprescribing Guideline and the evaluation of the guideline by testing concordance. Descriptive data on the incidence of PIMs identified were also assessed.

Results

A total of 61 patients were recruited. The OncPal Deprescribing Guideline matched 94 % of 617 medicines to the expert panel with a Kappa value of 0.83 [95 % CI (0.76, 0.89)] demonstrating an ‘outstanding’ concordance. Forty-three (70 %) patients were taking at least one PIM, with 21.4 % of the total medicines assessed identified as PIMs. The medication-associated cost per patient/month was AUD$26.71.

Conclusion

A guideline to assist in the de-escalation of inappropriate medications in palliative cancer patients was developed from current literature. The OncPal Deprescribing Guideline was successfully validated, demonstrating statistically significant concordance with an expert panel. We found that the incidence of PIMs was high in our patient group, demonstrating the potential benefits for the OncPal Deprescribing Guideline in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Fede A, Miranda M, Antonangelo D, Trevizan L, Schaffhausser H, Hamermesz B, Zimmermann C, Del Giglio A, Riechelmann RP (2011) Use of unnecessary medications by patients with advanced cancer: cross-sectional survey. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 19(9):1313–1318. doi:10.1007/s00520-010-0947-1

Jecker NS, Schneiderman LJ (1992) Futility and rationing. The American journal of medicine 92(2):189–196

Lindsay J, Dooley M, Martin J, Fay M, Kearney A, Barras M (2013) Reducing potentially inappropriate medications in palliative cancer patients: evidence to support deprescribing approaches. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-2098-7

Tollier C, Fusier I, Husson MC (2005) ATC and EphMRA classifications: evolution from 1996 to 2003 and comparative analysis. Therapie 60(1):47–56

Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher I, Reuben DB, Brooks J, Beck JC (1991) Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. UCLA Division of Geriatric Medicine Archives of internal medicine 151(9):1825–1832

Hwang SS, Scott CB, Chang VT, Cogswell J, Srinivas S, Kasimis B (2004) Prediction of survival for advanced cancer patients by recursive partitioning analysis: role of Karnofsky performance status, quality of life, and symptom distress. Cancer Investig 22(5):678–687

Gwilliam B, Keeley V, Todd C, Gittins M, Roberts C, Kelly L, Barclay S, Stone PC (2011) Development of prognosis in palliative care study (PiPS) predictor models to improve prognostication in advanced cancer: prospective cohort study. Bmj 343:d4920. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4920

Tredan O, Ray-Coquard I, Chvetzoff G, Rebattu P, Bajard A, Chabaud S, Perol D, Saba C, Quiblier F, Blay JY, Bachelot T (2011) Validation of prognostic scores for survival in cancer patients beyond first-line therapy. BMC Cancer 11:95. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-11-95

Sim J, Wright C (2005) The Kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther 85(3):257–268

Riechelmann RP, Krzyzanowska MK, Zimmermann C (2009) Futile medication use in terminally ill cancer patients. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 17(6):745–748. doi:10.1007/s00520-008-0541-y

De Muth JE (2009) Overview of biostatistics used in clinical research. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists 66(1):70–81. doi:10.2146/ajhp070006

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2013) Cancer statistics, 2013. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 63(1):11–30. doi:10.3322/caac.21166

AIHW & AACR (2012) Cancer in Australia: an overview. Cancer series Canberra: AIHW 74 (70)

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174

Australian Government Department of Health (2013) Pharmaceutical benefits scheme. Commonwealth of Australia. http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/home. Accessed 12/10/2013

Todd A, Williamson S, Husband A, Baqir W, Mahony M (2013) Patients with advanced lung cancer: is there scope to discontinue inappropriate medication? Int J Clin Pharm 35(2):181–184. doi:10.1007/s11096-012-9731-2

Conflict of interest

The authors had no financial relationship with the organization in which the research was conducted and have full control of all primary data. We agree to allow the journal to review the data if requested.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1 OncPal De-prescribing guideline

Appendix 1 OncPal De-prescribing guideline

This guideline has been developed to assist in highlighting medications with a limited benefit that are suitable targets for discontinuation in palliative cancer patients. Medication classes not listed below have demonstrated benefits in this population or the literature is lacking to guide a decision-making process. If the foreseeable benefits of any medications do NOT outweigh the adverse effects and/or associated risks, it is recommended to consider appropriate de-escalation

Medication class | Medication | Considerations for limited benefit | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

Blood and blood-forming organs | Aspirin | For primary prevention only. | Long-term benefits at population level. Little short or intermediate term risk of stopping (1). Drugs for primary prevention have, in general, no place in the treatment of end-of-life patients since the time-to-benefit usually exceeds life expectancy (2). |

Cardiovascular system | Dyslipidaemia medications Statins Fibrates Ezetimibe | All indications. | Long-term benefits at population level. Little short or intermediate term risk of stopping (1). |

Antihypertensives ACE inhibitors Sartans Beta blockers Calcium channel blockers Thiazide Diuretics | If sole use is to reduce mild to moderate hypertension for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events or as management of stable coronary artery disease.ab | Long-term benefits at population level. Ongoing therapy unnecessary in most shortened life expectancy (1). | |

Musculo-skeletal system | Osteoporosis medications Bisphosphonates Raloxifene Strontium Denosumab | Except if used for the treatment of hypercalcaemia secondary to bone metastases. | Except if used for the treatment of hypercalcaemia secondary to bone metastases. Long-term benefits at population level. Little short or intermediate term risk of stopping (1). |

Alimentary tract and metabolism | Peptic ulcer prophylaxis Proton pump inhibitors H2 antagonists | Lack of any medical history of gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcer, gastritis, GORD or the concomitant use of anti-inflammatory agents including NSAIDs and steroids (3). | Ongoing therapy unnecessary in most shortened life expectancy (1). |

Oral Hypoglycaemics Metformin Sulfonylureas Thiazolidinediones DPP-4 inhibitors GLP-1 analogues Acarbose | If sole use is to reduce mild hyperglycaemia for secondary prevention of diabetic associated events.c | Potential short-term complications outweigh benefit (1). | |

Vitamins Minerals Complementary—alternative medicines | If not indicated to treat a low blood plasma concentration. | No evidence for effectiveness (4, 5).d |

aSome short-term benefits need consideration—recommended to monitor blood pressure after discontinuation for symptomatic hypertension

bThe use of these agents in symptom management for an underlying disease should be continued. For example, antihypertensives in heart failure or rate control in irregular heart rhythm (6)

cSome short-term benefits need consideration—recommended to monitor blood sugar levels infrequently after discontinuation for symptomatic hyperglycaemia. Aim for blood sugar levels below 20mmols/L (7)

dSome topical preparations may provide some benefits (5)

1. Stevenson J, Abernethy AP, Miller C, Currow DC. Managing co-morbidities in patients at the end of life. BMJ. 2004;329 (7471):909–12

2. Holmes HM, Hayley DC, Alexander GC, Sachs GA. Reconsidering medication appropriateness for patients late in life. Archives of internal medicine. 2006;166 (6):605–9

3. Fede A, Miranda M, Antonangelo D, Trevizan L, Schaffhausser H, Hamermesz B, et al. Use of unnecessary medications by patients with advanced cancer: cross-sectional survey. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2011;19 (9):1313–8

4. Macpherson H, Pipingas A, Pase MP. Multivitamin-multimineral supplementation and mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2013;97 (2):437–44

5. Kassab S, Cummings M, Berkovitz S, van Haselen R, Fisher P. Homeopathic medicines for adverse effects of cancer treatments. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2009 (2):CD004845

6. Goodlin SJ, Hauptman PJ, Arnold R, Grady K, Hershberger RE, Kutner J, et al. Consensus statement: palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. Journal of cardiac failure. 2004;10 (3):200–9

7. McCoubrie R, Jeffrey D, Paton C, Dawes L. Managing diabetes mellitus in patients with advanced cancer: a case note audit and guidelines. European journal of cancer care. 2005;14 (3):244–8

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lindsay, J., Dooley, M., Martin, J. et al. The development and evaluation of an oncological palliative care deprescribing guideline: the ‘OncPal deprescribing guideline’. Support Care Cancer 23, 71–78 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2322-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2322-0