Abstract

The process of voice production is a complex process and depends on the correct interaction of the vocal folds and the glottal airstream inducing the primary voice source, which is subsequently modulated by the vocal tract. Due to the restricted access to the glottis, not all aspects of the three-dimensional process can be captured by measurements without influencing the measurement object. Hence, the application of a numerical tool capturing the physical process of phonation can provide an extended database for voice treatment and, therefore, can contribute to an increased effectiveness of voice treatment. However, such numerical models involve complex and demanding procedures to model the material behavior and the mechanical contact of the vocal folds and to realize moving boundaries of the involved physical domains. The present paper proposes a numerical model called simVoice, which circumvents these computational expenses by prescribing the experimentally obtained vocal fold motion within the simulation. Additionally, a hybrid approach for sound computation further enhances the computational efficiency and yields good agreement with acoustic measurements. An analysis of the computational workloads suggests that the key factor for a further increase in efficiency is an optimized flow simulation and source term computation.

Zusammenfassung

Der komplexe Vorgang der menschlichen Stimmerzeugung beruht auf dem richtigen Zusammenspiel der Stimmlippen und des glottalen Luftstroms, welcher ein erstes akustisches Signal erzeugt, das dann vom Vokaltrakt moduliert wird. Durch die eingeschränkte Zugänglichkeit zur Glottis können nicht alle Aspekte dieses dreidimensionalen Vorganges mittels Messungen erfasst werden, ohne das Messobjekt zu beeinflussen. Daher kann durch den Einsatz eines Simulationsmodells, welches die Physik der Stimmerzeugung wiedergibt, die Datenlage erweitert werden und somit die Treffsicherheit und Effektivität von Stimmbehandlungen verbessert werden. Solche numerischen Modelle erfordern jedoch komplexe und rechenintensive Verfahren, um einerseits das Materialverhalten des Gewebes zu modellieren und andererseits die räumlich verändernden physikalischen Gebiete bis zum mechanischen Kontakt der Stimmlippen zu realisieren. In diesem Paper wird das Modell simVoice präsentiert, das diesen numerischen Aufwand umgeht, indem die Bewegung der Stimmlippen in der Simulation aufgeprägt wird. Außerdem bewirkt ein hybrider Ansatz in der Aeroakustiksimulation zusätzliche numerische Effizienz und liefert eine gute Übereinstimmung mit Akustikmessungen. Eine Analyse des Rechenaufwandes der einzelnen Arbeitsschritte zeigt, dass für eine weitere Effizienzsteigerung an der Strömungssimulation bzw. der Quelltermberechnung angesetzt werden muss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The ability of humans to communicate is an essential characteristic that distinguishes us from other living beings and has played a crucial role in the evolution of the dominant species. People suffering from voice disorders have a reduced quality of life and today also poorer chances of professional success [4, 26, 42]. However, voice problems do not only affect the individual person, but are also of high social and economic relevance. A study in 2000 revealed that the annual losses within the Gross National Product of the USA are up to 186 billions dollars since approximately 10 percent of the entire US population are affected by communication disturbances [29].

The principal mechanism of voice generation is the self-sustained oscillation of the vocal folds (VFs) caused by the airstream coming from the lungs (see Fig. 1). Due to the vibrating vocal folds, the airstream is interrupted periodically generating acoustic waves dominated by the oscillation (fundamental) frequency \(f_{0}\). The arising primary voice source is subsequently modulated by the shape of the downstream oral and nasal airways referred as vocal tract.

In general, the purpose of numerical models of the human voice is either to gain a deeper insight into voice generation or a clinical application. Thereby, simVoice become a valuable clinical tool in phoniatrics by

-

contributing to a better understanding of pathological and physiological voice production,

-

helping to identify new treatment approaches,

-

predicting the outcome of conservative and surgical voice treatment, and

-

supporting training of medical stuff in phoniatrics.

For a patient specific application in a clinical environment, special focus in the development of the model simVoice must be put on computational efficiency, which is achieved by (1) applying the hybrid aeroacoustic approach based on the perturbed convective wave equation (PCWE) and (2) by circumventing fluid-structure interaction (FSI) modeling by prescribing the vocal fold motion (forward coupling).

Figure 2 illustrates the application of simVoice in a clinical environment as a tool supporting decision making, as well as for finding new treatment approaches. In the first step, the vocal fold motion is measured by high-speed imaging, and the voice of the patient is recorded. Furthermore, the geometry of the larynx and the vocal tract are obtained by magnetic resonance imaging (MRT) and the geometry and VF motion of the phonation model simVoice is adapted to the patient specific physiology. Subsequently, the geometry of the numerical model is modified according to the chosen treatment approach (e.g. surgical treatment), which is thought to yield an improvement of voice quality. In the next step, the voice of the modified geometry is computed by the numerical model. If the resulting voice quality is satisfying, the selected treatment can be performed. Otherwise, the geometry is modified again until a satisfying result is obtained. Thus, an efficient numerical model capturing the crucial physical aspects of phonation will contribute to a more effective treatment of voice disorders.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, the state of art and a classification of numerical phonation models is provided and in Sect. 3, the methodology of simVoice is presented according to the simulation workflow. The model of the larynx and the vocal fold motion is illustrated in Sect. 3.1 and the hybrid workflow is explained in Sect. 3.2 including the derivation of the governing equation for flow-induced sound generation and propagation. Subsequently, the steps of the hybrid workflow, namely the computational fluid dynamics simulation, aeroacoustic source term computation and interpolation, and computation of the acoustic field are presented within Sect. 3.2, before analyzing the computational efficiency of the phonation model (Sect. 4.1) and showing validation results (Sect. 4). Finally, a conclusion including an outlook are provided (Sect. 5).

2 Background

The interaction of fluid dynamics (airflow), structural mechanics of the VFs (tissue), and acoustics (air), which is the principal mechanism of voice production, can be described in different levels of complexity. On a fundamental level, models of human phonation can be distinguished between lumped mass models and models based on continuum mechanics with the respective governing partial differential equation (PDE) according to Fig. 3. For the latter approach, the governing PDEs are typically solved by a finite volume method (FVM), finite element method (FEM), or finite difference method (FDM). PDE-based models can be further classified by the motion of the vocal folds, which can be static, externally driven (prescribed motion) or self-excited due to fluid-structure-acoustic interaction (FSAI). Another crucial model property is dimensionality which has a substantial impact on the degrees of freedom (DOFs) and hence computation time. Thereby, it has to be noted that only three dimensional (3D) models are capable of reflecting the real physics since flow turbulence, which is a dominating phenomenon of phonation, requires three dimensions for a correct physical representation(vorticity distribution) [25].

Lumped mass models

While lumped mass models were used in the past for principal investigations of the self-excited oscillation of the vocal folds [8, 12], they are still applied nowadays but in a three-dimensional (3D) arrangement (multi-mass models) to investigate material properties of the vocal folds [44, 45]. Due to the strong simplifications of this modeling approach, not all physical aspects can be captured. Therefore, PDE-based tools, which aim to resolve all physical details, are more promising for principal research as well as for clinical applications, which can be classified by the modeling approach of the vocal fold motion.

Self excited (FSI) PDE-based models

The most general approach is to model the interaction of the airflow and the structural mechanics of the vocal folds, which yields the self-excited oscillation of the vocal folds for certain flow and mechanic parameters. A first model considering fluid-structure interaction was introduced by Alipour et al. [1]. Thereby, the domain alteration was realized by mesh deformation, which induces distorted flow cells within the glottis. Thus, the immersed boundary method (IBM) was later applied [5, 13, 46–48], which does not have this drawback. Besides ensuring the boundary conditions of the moving domain boundaries, a material model of the anisotropic tissue of the vocal folds has to be established. These two tasks require complex numeric procedures and high computational effort, which makes them not yet applicable in a clinical environment.

PDE-based models with static vocal folds

This modeling approach assumes a quasi-steady condition at specific instances in the oscillation cycle and aims to investigate the glottal aerodynamics but does not allow a thorough acoustic analysis [11, 24, 32].

Externally driven PDE-based models

Kaltenbacher et al. established a 2D FSAI-model which takes fluid-acoustic coupling into account by deploying acoustic perturbation equations within a hybrid aeroacoustic approach [17]. This model was simplified by Zörner et al., who replaced the fully-coupled interface condition by a one-way coupling [49]. Therewith, the costly coupled simulation was reduced to a pure computational fluid dynamic (CFD) simulation with a prescribed movement of the vocal folds and appropriate boundary conditions. In general, the presented results showed that a pure CFD-simulation with a prescribed structural movement can substitute the fully-coupled approach [49]. In simVoice, this modeling approach is applied in combination with a hybrid aeroacoustic approach based on the perturbed convective wave equation. The detailed description of the model with focus on the numerical efficiency is provided in [37], whereas a thorough description of the CFD incompressible flow simulation can be found in [31] and [30]. Furthermore, an extensive source term analysis for a validated synthetic setup is provided in [36] and the application to typical vocal cord dysfunctions is presented in [7].

3 Methods

Figure 4 illustrates the workflow of simVoice which is based on the hybrid aeroacoustic approach (Sect. 3.2) consisting of (1) a flow simulation, (2) an acoustic source term computation and interpolation and (3) an acoustic propagation simulation. Thereby, the acoustic source term excites the acoustic field and is defined by the right hand side of a the acoustic wave equation governing the propagation simulation and hence features the excitation of the acoustic field. In the acoustic propagation simulation, the VFs are fixed, whereas in the flow simulation they are externally driven. Therefore, the VF motion is obtained by fitting a vocal fold model (Sect. 3.1) to real physiological VF oscillations captured by glottal endoscopy.

3.1 Geometry and vocal fold model

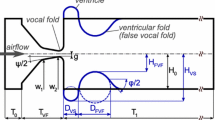

For modeling the VF-motion, the commonly used M5 model with two degrees of freedom (DOFs) and a sinusoidal glottal orifice is chosen (see Fig. 5) [33]. Thereby, each vocal fold has a degree of freedom (DOF) of translation \(y\) and rotation-DOF \(\phi \). Due to the rotation-DOF, the model is able to capture the characteristic convergent-to-divergent shape change of the glottal duct during an oscillation cycle [21, 22]. Furthermore, typical abnormalities and pathologies of vocal fold vibration, such as glottal insufficiency (incomplete VF closure), aperiodic or asymmetric oscillation can be reproduced. Figure 7 illustrates the VF model and provides the main dimensions, of the larynx. The false vocal folds (fVFs), also known as ventricular folds are modeled rigid since they are not excited by the glottal airstream. The temporal evolutions of the DOFs \(y\) and \(\phi \) are fitted to reproduce the measured glottal area waveform (GAW, see Fig. 6), which describes the temporal evolution of the area of the glottal orifice and can be obtained by high-speed videoendoscopy measurements during phonation in excised larynges (ex-vivo), as well as in living individuals (in-vivo). The vocal fold shape in the closed and the opened condition is shown in Fig. 7. Due to numerical issues of the flow solver, a gap of \(h_{\mathrm{{min}}}=0.2\) mm is remaining in the closed condition. A more detailed description of the applied vocal fold model and larynx geometry including the shape of the false vocal folds (ventricular folds) can be found in [30, 31].

Glottal area waveform and evolvement of \(\phi (t)\) and \(y(t)\) with indication of the divergent and convergent phase of the synthetic glottal oscillation cycle according to [33]

In the current version of simVoice, a simplified straight vocal tract with circular cross-sections according to [28] is used (see Fig. 8). Compared to a realistic physiological shape, the model complexity is reduced significantly while preserving the acoustic properties. A more detailed description of the simplification procedure can be found in [2, 28].

3.2 Hybrid aeroacoustic approach

simVoice is based on the hybrid aeroacoustic approach which decomposes the task of sound computation into a flow computation and an acoustic propagation simulation [35]. For the latter part, the aeroacoustic source terms depending on the partial differential equation (PDE) governing the acoustic field (such as Lighthill acoustic analogy, acoustic perturbation equations, etc.) have to be computed from the flow field obtained in the first step [35]. The hybrid approach is commonly applied in computational aeroacoustics (CAA) [3, 16, 18, 27, 39–41] due to several advantages:

-

Adjustment of simulation features to the specific requirements of the respective physical field. Since the characteristics and dominating phenomena of the flow and the acoustic field differ substantially, the numerical computation of these fields has their specific requirements:

-

Spatial discretization. The element size can be chosen individually for the flow and acoustic field (i.e. handle the disparity of length scales). Whereas in fluid dynamics boundary layers and turbulent eddies need to be resolved, in acoustics the acoustic waves have to be resolved. Furthermore, the domain of flow and acoustic simulation can differ. Fluid domain without an impact on the flow and containing no acoustic sources, such as acoustic propagation regions, can be neglected for the flow simulation.

-

Temporal resolution. While the minimum time step size of acoustics is defined by the maximum resolved frequency of the acoustic wave, the minimum time step size of CFD, in general, depends on turbulent phenomena that must be resolved.

-

-

Assumption of incompressible flow within the CFD simulation. For low Mach number flows (\(Ma<0.3\)), compressibility can be neglected and solving the incompressible Navier Stokes equations is sufficient for the subsequent acoustic source term computation. Thus, the computational demanding compressible flow simulation can be avoided.

In many applications, the reduction of computational effort due to valid simplification of the flow simulation outweighs the additional effort due to the acoustic simulation and the acoustic source term computation and treatment. Furthermore, when the source term computation is performed on the fly within the CFD-export, the additional effort is decreased.

For the present model, the perturbed convective wave equation (PCWE) is chosen to model the sound generation and propagation inside the acoustic domain. An advantage of this wave equation is its numerical efficiency, since it is a PDE with only one scalar unknown being the acoustic velocity potential \(\psi ^{\mathrm{a}}\). The derivation of so-called acoustic perturbation equations (APEs) [6] is based on the perturbation ansatz, which is applied to the quantities of the flow field

according to [9]. Therewith, the pressure \(p\), the flow velocity \(\boldsymbol{v}\), and the density \(\rho \) are decomposed into a mean part (\(\bar{p}\), \(\bar {\boldsymbol{v}}\), \(\bar{\rho}\)) and a fluctuating part consisting of acoustic (\(p^{\mathrm{a}}\), \(\boldsymbol{v}^{\mathrm{a}}\), \(\rho ^{\mathrm{a}}\)) and incompressible flow components (\(p^{\mathrm{ic}}\), \(\boldsymbol{v}^{\mathrm{ic}}\)). Additionally, a density correction \(\rho _{1}\) is introduced.

By applying the splitting approach to the compressible flow equations, the APE-2 system can be derived [6], which was reformulated by Hüppe and Kaltenbacher [10, 15] to

by introducing the acoustic velocity potential \(\psi ^{\mathrm{a}}\) defined as

Thereby, the material parameters \(\bar{\rho}\) (incompressible fluid density) and \(c\) (speed of sound) depend on the condition of the airstream. For in-vivo phonation, the material parameters are set to \(\rho =1.145~\mbox{kg}\,\mbox{m}^{-3}\) and \(c=355~\mbox{m}\,\mbox{s}^{-1}\) corresponding to the condition of expiration air (\(T\approx 35\ {}^{\circ}\mbox{C}\), 95% relative humidity) whereas ex-vivo investigations ambient conditions have to be considered. The PDE describes aeroacoustic sources generated by incompressible flow structures and wave propagation through moving media. Since the solution quantity is a scalar unknown, this form has an enhanced numerical efficiency compared to the APE-2 system. The differential operator (material derivative) in Eq. (4) is defined by

consisting of the partial time derivative and a convective term, where \(\overline{ \boldsymbol{v}}\) is the mean velocity. The right-hand side (RHS) of Eq. (4) defines the aeroacoustic source term

wherein the convective term can be neglected for low flow velocities \(\overline{ \boldsymbol{v}}\) due to the dominating partial time derivative especially at high frequencies. Since low flow velocity applies to human phonation, the simplification is exploited.

When the mean flow \(\overline{ \boldsymbol{v}}\) is also neglected in the wave operator on the left-hand side of Eq. (4), the weak formulation of the PCWE (4) reads as

with \(\varphi \) denoting the test function and the integrals being defined in the computational domain \(\Omega \) (volume term) and its boundary \(\Gamma \) (boundary term). This weak form of the PCWE is solved by the FE-based multi-physics solver openCFS for the solution quantity \(\psi ^{\mathrm{a}}\) [43]. The relation \(p^{\mathrm{a}}= \bar{\rho}\frac{D\psi ^{\mathrm{a}}}{D t}\) allows the calculation of the acoustic pressure \(p^{\mathrm{a}}\).

1) Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation

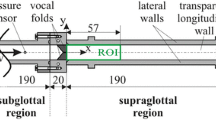

To provide the flow field for the subsequent acoustic source term computation, the unsteady incompressible Navier-Stokes equations are solved by the CFD software Star-CCM+ (Siemens PLM Software, Plano, TX/USA). Compressible effects can be neglected due to the low flow velocity (mean convective Mach number inside the glottis \({\overline{ \mathrm{Ma}}} < 0.1\)). The computational domain comprises the larynx and the downstream vocal tract (Fig. 5). The overset mesh algorithm of Star-CCM+ is used to realize the vocal fold motion, which is based on the above introduced M5-model. This procedure does not allow full closure of the vocal folds. Thus, a gap of 0.2 mm is remaining in the closed condition, which causes a negligible leakage flow. A large eddy simulation (LES) in combination with the wall-adapting local eddy-viscosity (WALE) subgrid-scale model is used to model the turbulent flow. The computational grid consists of about 1.3 million hexahedral cells with two levels of refinement within the glottal region. Further details about the flow simulation can be found in [30, 31]. In Fig. 8 the resulting flow field at \(t=0.5\, T\) is visualized by means of streamlines.

2) Aeroacoustic source term computation and interpolation

Having determined the evolution of the flow field, the simplified acoustic source term of Eq. (7) can be computed on the CFD grid. The resulting source term at the time instance \(t=0.5\, T\) is displayed in Fig. 9. In a next step, the source term has to be interpolated from the CFD grid to the generally coarser acoustic grid (see Fig. 10). This is realized by a conservative interpolation scheme, which considers the intersection volumes of flow and acoustic cells and hence conserves the energy globally, as well as locally [34, 37, 38].

3) Computational acoustics simulation

Figure 11 shows the acoustic simulation setup. The static computational domain covers the CFD domain at the maximum opening of the vocal folds in order to capture all acoustic sources. The vocal fold motion can be neglected for the acoustic simulation because the glottal gap is acoustically compact since

where \(h_{\mathrm{{max}}}=4~\mbox{mm}\) denotes the maximum glottal gap and \(f_{\mathrm{{max}}}=5~\mbox{kHz}\) the maximum resolved frequency. Thus, the changing acoustic domain has no impact on the wave propagation within the considered frequency range. In addition to the larynx and vocal tract, a propagation region is added, which represents the ambient air, where the voice is emitted. The adjacent perfectly matched layer (PML) region ensures free field radiation at the boundary [14], whereas at the larynx inlet wave reflections are avoided by an absorbing boundary condition (ABC) [14] at \(\Gamma _{\mathrm{{inlet}}}\). Compared to a PML, the ABC does not introduce additional DOFs but provides full absorption just for plane waves, which applies to the present model because

with \(H\) being the larger dimension of the duct cross-section (see Fig. 5) The remaining bounding surface \(\Gamma _{\mathrm{{wall}}}\) is modeled sound-hard by setting the acoustic particle velocity normal to the wall \(v_{n}=\nabla \psi ^{\mathrm{a}}\cdot \boldsymbol{n}\) to zero (natural boundary condition). In order to preserve element quality and meshing flexibility a non-conforming interface of type Nitsche is applied between the vocal tract and the propagation region, which is also implemented in openCFS [43]. The shape of the vocal tract in Fig. 11 is simplified from a realistic MRI-based human vocal tract (corresponding to the vowel ‘a’) to a straight rotational symmetric shape while preserving the acoustic filter characteristics according to the procedure presented in [2].

The simulation setup is the result of a convergence study presented in [37]. Therein, the element size, the number of elements within the PML, and further aspects were successively modified to obtain an efficient acoustic simulation setup. An overview of cell sizes and element numbers is provided in Table 1. While the propagation region with adjacent PML region is meshed by linear hexahedral elements, linear tetrahedral cells are used for the larynx and the vocal tract to ensure an efficient mesh generation of complex structures. In total, the acoustic grid of the displayed configuration consists of \(93\, 200\) elements.

4 Results

In order to validate the numerical model simVoice, a measurement on a test rig with artificial vocal folds (M5-shaped) out of silicone and a simple cuboid-shaped vocal tract out of aluminum was performed [19, 20, 22, 23]. Thereby, the shape of the larynx and the vocal tract of the measurement and the simulation agreed. Figure 12 shows the resulting acoustic spectra of the measurement of 20 oscillation cycles of the VFs and the simulation, where the parts of the acoustic source term in Eq. (7) were considered separately as well as combined. The plot proofs that neglecting the convective source term is valid since its consideration only changes the spectrum insignificantly. Above 300 Hz, the spectrum of the measurement is well reproduced by the simulation. Reflections of the acoustic waves at the walls of the anechoic room in the measurement are thought to be the reason for the underestimation of the amplitude by the simulation underneath 300 Hz since this is the cut-off frequency of the anechoic room. A detailed description of the experimental setup is published in [19, 20, 22, 23].

4.1 Computational efficiency

Since the goal of the present research work is a clinical application, a special focus is put on computational efficiency which is a crucial factor for the applicability in a clinical environment for patient specific treatment approaches. Table 2 summarizes the simulation details of the principal computational tasks of the hybrid workflow. It clearly shows that the bottleneck of the workflow is the CFD simulation demanding 94.5% of the total computation time. However, this emphasizes the potential of the hybrid approach in terms of computational efficiency, since the effort due to tasks introduced by the hybrid approach, is only about 5.5%. Therefore, the reduction of computational effort due to simplifications on the flow simulation (incompressible flow, reduction of computational domain) clearly outweighs the additional effort owing to the hybrid approach (source term computation and interpolation and acoustic propagation simulation). Moreover, circumventing FSI of the airflow and the vocal folds yields a massive reduction of computation time since the tissue has not to be discretized (no additional DOFs), no material model of the tissue is required and complex algorithms treating the moving boundary (VF surface) are avoided.

5 Conclusion

A numerical model called simVoice, which is capable of predicting the voice based on a measured vocal fold motion and the geometry of the larynx and vocal tract was presented. The hybrid aeroacoustic approach based on the PCWE and the prescribed vocal fold motion, which circumvents modeling fluid-structure interaction, contributes to the high numerical efficiency of the model. However, the CFD simulation is still too computationally challenging to be performed on a conventional computer. Thus, special effort will be put into an efficiency-optimized flow simulation and source term computation. Moreover, the application of stochastic methods and artificial intelligence for the multiplication of flow data of a reduced number of oscillation cycles will be investigated. Nevertheless, numerical models capturing the crucial physical aspects of phonation will develop in the future and have the potential to support clinical work and to contribute to a deeper understanding of human voice production.

References

Alipour, F., Berry, D. A., Titze, I. R. (2000): A finite-element model of vocal-fold vibration. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 108(6), 3003–3012. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1324678.

Arnela, M., Dabbaghchian, S., Blandin, R., Guasch, O., Engwall, O., Van Hirtum, A., Pelorson, X. (2016): Influence of vocal tract geometry simplifications on the numerical simulation of vowel sounds. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 140(3), 1707–1718.

Caro, S., Detandt, Y., Manera, J., Mendonca, F., Toppinga, R. (2009): Validation of a new hybrid CAA strategy and application to the noise generated by a flap in a simplified HVAC duct. In 15th AIAA/CEAS aeroacoustics conference (pp. 2009–3352).

Cohen, S. M. (2010): Self-reported impact of dysphonia in a primary care population: an epidemiological study. Laryngoscope, 120(10), 2022–2032.

Duncan, C., Zhai, G., Scherer, R. (2006): Modeling coupled aerodynamics and vocal fold dynamics using immersed boundary methods. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 120(5), 2859–2871. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.2354069.

Ewert, R., Schröder, W. (2003): Acoustic perturbation equations based on flow decomposition via source filtering. J. Comput. Phys., 188(2), 365–398.

Falk, S., Kniesburges, S., Schoder, S., Jakubaß, B., Maurerlehner, P., Echternach, M., Kaltenbacher, M., Döllinger, M. (2021): 3D-FV-FE aeroacoustic larynx model for investigation of functional based voice disorders. Front. Physiol., 12, 226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.616985. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphys.2021.616985.

Flanagan, J., Landgraf, L. (1968): Self-oscillating source for vocal-tract synthesizers. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust., 16(1), 57–64.

Hardin, J. C., Pope, D. S. (1994): An acoustic/viscous splitting technique for computational aeroacoustics. Theor. Comput. Fluid Dyn., 6(5), 323–340.

Hüppe, A., Grabinger, J., Kaltenbacher, M., Reppenhagen, A., Dutzler, G., Kühnel, W. (2014): A non-conforming finite element method for computational aeroacoustics in rotating systems. In 20th AIAA/CEAS aeroacoustics conference (pp. 2014–2739).

Ishizaka, K. (1972): Fluid mechanical considerations of vocal cord vibration. SCRL Monogr., 8, 28–72.

Ishizaka, K., Flanagan, J. L. (1972): Synthesis of voiced sounds from a two-mass model of the vocal cords. Bell Syst. Tech. J., 51(6), 1233–1268.

Jiang, W., Zheng, X., Xue, Q. (2017): Computational modeling of fluid–structure–acoustics interaction during voice production. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., 5, 7.

Kaltenbacher, M. (2015): Numerical simulation of mechatronic sensors and actuators: finite elements for computational multiphysics. Berlin: Springer.

Kaltenbacher, M. (2017): Computational acoustics. CISM international centre for mechanical sciences. Berlin: Springer.

Kaltenbacher, M., Hüppe, A., Reppenhagen, A., Tautz, M., Becker, S., Kuehnel, W. (2016): Computational aeroacoustics for HVAC systems utilizing a hybrid approach. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars - Mech. Syst., 9, 1047–1052.

Kaltenbacher, M., Zörner, S., Hüppe, A. (2014): On the importance of strong fluid-solid coupling with application to human phonation. Prog. Comput. Fluid Dyn., 14(1), 2–13.

Kierkegaard, A., West, A., Caro, S. (2016): HVAC noise simulations using direct and hybrid methods. In 22nd AIAA/CEAS aeroacoustics conference (pp. 2016–2855).

Kniesburges, S., Lodermeyer, A., Becker, S., Traxdorf, M., Döllinger, M. (2016): The mechanisms of subharmonic tone generation in a synthetic larynx model. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 139(6), 3182–3192.

Kniesburges, S., Lodermeyer, A., Semmler, M., Schulz, Y. K., Schützenberger, A., Becker, S. (2020): Analysis of the tonal sound generation during phonation with and without glottis closure. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 147(5), 3285–3293.

Liljencrants, J. (1991): A translating and rotating mass model of the vocal folds. STL-QPSR, 32(1), 1–18.

Lodermeyer, A., Becker, S., Döllinger, M., Kniesburges, S. (2015): Phase-locked flow field analysis in a synthetic human larynx model. Exp. Fluids, 56(4), 77.

Lodermeyer, A., Tautz, M., Becker, S., Döllinger, M., Birk, V., Kniesburges, S. (2018): Aeroacoustic analysis of the human phonation process based on a hybrid acoustic PIV approach. Exp. Fluids, 59(1), 13.

de Luzan, C. F., Chen, J., Mihaescu, M., Khosla, S. M., Gutmark, E. (2015): Computational study of false vocal folds effects on unsteady airflows through static models of the human larynx. J. Biomech., 48(7), 1248–1257.

Mattheus, W., Brücker, C. (2011): Asymmetric glottal jet deflection: differences of two- and three-dimensional models. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 130(6), EL373–EL379. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3655893.

Merrill, R. M., Anderson, A. E., Sloan, A. (2011): Quality of life indicators according to voice disorders and voice-related conditions. Laryngoscope, 121(9), 2004–2010.

Piellard, M., Bailly, C. (2009): A hybrid method for computational aeroacoustic applied to internal flows. In NAG-DAGA international conference on acoustics. NAGDAGA2009/369.

Probst, J., Lodermeyer, A., Fattoum, S., Becker, S., Echternach, M., Richter, B., Döllinger, M., Kniesburges, S. (2019): Acoustic and aerodynamic coupling during phonation in MRI-based vocal tract replicas. Appl. Sci., 9(17), 3562.

Ruben, R. J. (2000): Redefining the survival of the fittest: communication disorders in the 21st century. Laryngoscope, 110(2), 241–245.

Sadeghi, H., Kniesburges, S., Falk, S., Kaltenbacher, M., Schützenberger, A., Döllinger, M. (2019): Towards a clinically applicable computational larynx model. Appl. Sci., 9(11), 2288. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9112288.

Sadeghi, H., Kniesburges, S., Kaltenbacher, M., Schützenberger, A., Döllinger, M. (2018): Computational models of laryngeal aerodynamics: potentials and numerical costs. J. Voice. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.01.001.

Scherer, R. C., De Witt, K. J., Kucinschi, B. R. (2001): The effect of exit radii on intraglottal pressure distributions in the convergent glottis. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 110(5), 2267–2269.

Scherer, R. C., Shinwari, D., De Witt, K. J., Zhang, C., Kucinschi, B. R., Afjeh, A. A. (2001): Intraglottal pressure profiles for a symmetric and oblique glottis with a divergence angle of 10 degrees. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 109(4), 1616–1630.

Schoder, S., Junger, C., Weitz, M., Kaltenbacher, M. (2019): Conservative source term interpolation for hybrid aeroacoustic computations. In 25th AIAA/CEAS aeroacoustics conference (pp. 2019–2538).

Schoder, S., Kaltenbacher, M. (2019): Hybrid aeroacoustic computations: state of art and new achievements. J. Theor. Comput. Acoust., 27(4), 1950,020.

Schoder, S., Maurerlehner, P., Wurzinger, A., Hauser, A., Falk, S., Kniesburges, S., Döllinger, M., Kaltenbacher, M. (2021): Aeroacoustic sound source characterization of the human voice production-perturbed convective wave equation. Appl. Sci., 11(6), 2614. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11062614. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/11/6/2614.

Schoder, S., Weitz, M., Maurerlehner, P., Hauser, A., Falk, S., Kniesburges, S., Döllinger, M., Kaltenbacher, M. (2020): Hybrid aeroacoustic approach for the efficient numerical simulation of human phonation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 147(2), 1179–1194.

Schoder, S., Wurzinger, A., Junger, C., Weitz, M., Freidhager, C., Roppert, K., Kaltenbacher, M. (2021): Application limits of conservative source interpolation methods using a low Mach number hybrid aeroacoustic workflow. J. Theor. Comput. Acoust., 29(01), 2050032.

Schröder, T., Silkeit, P., Estorff, O. (2016): Influence of source term interpolation on hybrid computational aeroacoustics in finite volumes. In InterNoise 2016 (pp. 1598–1608).

Schwertfirm, F., Kreuzinger, J., Peller, N., Hartmann, M. (2012): Validation of a hybrid simulation method for flow noise prediction. In 18th AIAA/CEAS aeroacoustics conference, 33rd AIAA Aeroacoustics Conference (pp. 2012–2192).

Šidlof, P., Zörner, S., Hüppe, A. (2015): A hybrid approach to the computational aeroacoustics of human voice production. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol., 14(3), 473–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10237-014-0617-1.

Smith, E., Verdolini, K., Gray, S., Nichols, S., Lemke, J., Barkmeier, J., Dove, H., Hoffman, H. (1996): Effect of voice disorders on quality of life. J. Med. Speech-Lang. Pathol., 4(4), 223–244.

Verein zur Förderung der Software openCFS: openCFS—Multiphysics and more based on the finite element method (2020). www.opencfs.org.

Yang, A., Berry, D. A., Kaltenbacher, M., Döllinger, M. (2012): Three-dimensional biomechanical properties of human vocal folds: parameter optimization of a numerical model to match in vitro dynamics. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 131(2), 1378–1390.

Yang, A., Lohscheller, J., Berry, D. A., Becker, S., Eysholdt, U., Voigt, D., Döllinger, M. (2010): Biomechanical modeling of the three-dimensional aspects of human vocal fold dynamics. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 127(2), 1014–1031.

Zheng, X., Bielamowicz, S., Luo, H., Mittal, R. (2009): A computational study of the effect of false vocal folds on glottal flow and vocal fold vibration during phonation. Ann. Biomed. Eng., 37(3), 625–642.

Zheng, X., Mittal, R., Bielamowicz, S. (2011): A computational study of asymmetric glottal jet deflection during phonation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 129(4), 2133–2143.

Zheng, X., Mittal, R., Xue, Q., Bielamowicz, S. (2011): Direct-numerical simulation of the glottal jet and vocal-fold dynamics in a three-dimensional laryngeal model. J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 130(1), 404–415.

Zörner, S., Kaltenbacher, M., Döllinger, M. (2013): Investigation of prescribed movement in fluid-structure interaction simulation for the human phonation process. Comput. Fluids, 86, 133–140.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) under DO 1247/10-1 (no. 391215328) and the Austrian Research Council (FWF) under no. I 3702.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Graz University of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access Dieser Artikel wird unter der Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz veröffentlicht, welche die Nutzung, Vervielfältigung, Bearbeitung, Verbreitung und Wiedergabe in jeglichem Medium und Format erlaubt, sofern Sie den/die ursprünglichen Autor(en) und die Quelle ordnungsgemäß nennen, einen Link zur Creative Commons Lizenz beifügen und angeben, ob Änderungen vorgenommen wurden. Die in diesem Artikel enthaltenen Bilder und sonstiges Drittmaterial unterliegen ebenfalls der genannten Creative Commons Lizenz, sofern sich aus der Abbildungslegende nichts anderes ergibt. Sofern das betreffende Material nicht unter der genannten Creative Commons Lizenz steht und die betreffende Handlung nicht nach gesetzlichen Vorschriften erlaubt ist, ist für die oben aufgeführten Weiterverwendungen des Materials die Einwilligung des jeweiligen Rechteinhabers einzuholen. Weitere Details zur Lizenz entnehmen Sie bitte der Lizenzinformation auf http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de.

About this article

Cite this article

Maurerlehner, P., Schoder, S., Freidhager, C. et al. Efficient numerical simulation of the human voice. Elektrotech. Inftech. 138, 219–228 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00502-021-00886-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00502-021-00886-1

Keywords

- human voice production

- voice disorders

- computational biomechanics

- computational aeroacoustics (CAA)

- computational fluid dynamics (CFD)