Abstract

The following natural problem was raised independently by Erdős–Hajnal and Linial–Rabinovich in the early ’90 s. How large must the independence number \(\alpha (G)\) of a graph G be whose every m vertices contain an independent set of size r? In this paper, we discuss new methods to attack this problem. The first new approach, based on bounding Ramsey numbers of certain graphs, allows us to improve the previously best lower bounds due to Linial–Rabinovich, Erdős–Hajnal and Alon–Sudakov. As an example, we prove that any n-vertex graph G having an independent set of size 3 among every 7 vertices has \(\alpha (G) \ge \Omega (n^{5/12})\). This confirms a conjecture of Erdős and Hajnal that \(\alpha (G)\) should be at least \(n^{1/3+\varepsilon }\) and brings the exponent halfway to the best possible value of 1/2. Our second approach deals with upper bounds. It relies on a reduction of the original question to the following natural extremal problem. What is the minimum possible value of the 2-density (The 2-density of a graph H is defined as \(m_2(H):=\max _{H' \subseteq H, |H'| \ge 3} \frac{e(H')-1}{|H'|-2}\)) of a graph on m vertices having no independent set of size r? This allows us to improve previous upper bounds due to Linial–Rabinovich, Krivelevich and Kostochka-Jancey. As part of our arguments, we link the problem of Erdős–Hajnal and Linial–Rabinovich and our new extremal 2-density problem to a number of other well-studied questions. This leads to many interesting directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In this paper, we study the following classical problem. If we know that any m vertices of a graph contain an independent set of order r how large can the independence number of the whole graph be? The study of this problem for a specific choice of parameters dates back almost 60 years, with the first published result being due to Erdős and Rogers [13] in 1962.

Over the years this problem attracted a lot of attention. Originally the focus was on the instance of the problem in which we keep the sizes of independent sets we want to find locally and in the whole graph to be fixed and small. In other words, if we forbid in G an independent set of size s, how big a subset of vertices one can find without an independent set of size r? Choosing \(r=2\) precisely recovers the usual Ramsey problem and was in fact the original motivation behind the general question. This question became known as the Erdős–Rogers problem and has been extensively studied, for some examples see [9, 11, 13, 20, 25, 37,38,39] and a recent survey [10] due to Dudek and Rödl.

In the early 90’s Erdős and Hajnal [12] and independently Linial and Rabinovich [30] propose changing the perspective and fixing the local parameters m and r instead. In other words, asking what can be said about the independence number of the whole graph if we know that any small number of vertices m contain an independent set of size r. This frames the problem squarely under the so-called local–global principle, stating that one can obtain global understanding of a structure from having a good understanding of its local properties, or vice versa. This phenomenon has been ubiquitous in many areas of mathematics and beyond, see e.g. [5, 18, 19, 29]. In fact, one can define an m-local independence number \(\alpha _m(G)\) of a graph G to be the minimum independence number we can find among subgraphs of G on m vertices and the problem becomes relating the local independence number to the independence number of G itself, the “global” independence number. In particular, we are interested in the smallest possible size of \(\alpha (G)\) in an n-vertex graph satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\).

In this paper we discuss two new approaches for attacking this problem, which allow us to significantly improve previously best-known bounds due to Linial and Rabinovich [30], Erdős–Hajnal [12], Alon and Sudakov [4], Krivelevich [26] and Kostochka and Jancey [24]. In the case of lower bounds, we improve their results for at least half of the possible choices of m and r and in the case of upper bounds for essentially all choices. Moreover, we believe that both approaches have the potential for further improvements.

The initial approach of Linial and Rabinovich [30] and independently Alon and Sudakov [4] reduces the lower bound problem to the question of bounding from above Ramsey numbers of a clique of size \(k=\lceil {\frac{m}{r-1}} \rceil \) vs a large independent set. Our new idea is that one can find other “forbidden” graphs whose Ramsey numbers perform better. For this to work we need to obtain upper bounds on the Ramsey numbers of our new graphs vs a large independent set, which often turns out to be an interesting problem in its own right. See the beginning of Sect. 2.1 for a more detailed illustration of our new approach.

The above-introduced parameter k controls in large part the known lower bounds for \(\alpha (G)\) among all graphs satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\). Linial and Rabinovich [30] determine the answer precisely if \(k \le 2\), i.e. for \(m \le 2r-2\). For \(k=3\), they show that an n vertex graph satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\) must have \(\alpha (G) \ge n^{1-\frac{2}{r-1}-o(1)}\) if \(m=2r-1\) and \(\alpha (G) \ge \Omega (n^{1/2})\) for the rest of the range \(m \le 3r-3\). Our first result improves the exponent in their bounds for the first half of this range. Moreover, the improvement in the exponent is by a constant factor independent of r, unless \(m = 2r-1\).

Proposition 1.1

Let \(m=2r-2+t\) for \(1 \le t \le r-1\). Then any n-vertex graph G satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\) has \(\alpha (G) \ge \Omega (n^{1-1/\ell }),\) where \(\ell =\lfloor {\frac{r-1}{t}} \rfloor +1\).

In the general case of \(k \ge 4\), Linial and Rabinovich and independently Alon and Sudakov show that an n-vertex graph satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\) must have \(\alpha (G) \ge \Omega (n^{\frac{1}{k-1}}).\) We improve the exponent in these bounds for the first half of the range for any k.

Theorem 1.2

Let \(k=\lceil {\frac{m}{r-1}} \rceil \) and let us assume \(m \le (k-\frac{1}{2})(r-1).\) Then any n-vertex graph G satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\) has \(\alpha (G) \ge \Omega (n^{\frac{1}{k-3/2}})\).

Going beyond \(k-2\) in the denominator of the exponent in the above theorem seems likely to require an improvement over the best-known upper bounds on Ramsey numbers, which have not seen an improvement in the exponent since the initial paper of Erdős and Szekeres [14] from 1935. This means our result is in some sense halfway between the previously best bound and the Ramsey barrier.

The key part of the above result is actually the special case of \(r=3\). This is due to an easy observation which allows us to generalise any improvement in this case to the first half of the range as above, for any r. The first interesting instance here, which actually lead us to the general improvements above, is \(m=7\) and \(r=3\) in which case we can obtain an even better bound. Studying this case was explicitly proposed by Erdős and Hajnal [12] who observed that any graph G on n vertices with \(\alpha _7(G) \ge 3\) must have \(\alpha (G) \ge \Omega (n^{1/3})\) and that such a graph G exists with \(\alpha (G) \le O(n^{1/2})\). They conjectured that neither of these bounds is tight. Our next result confirms their first conjecture.

Theorem 1.3

Any n-vertex graph G with \(\alpha _7(G) \ge 3\) has \(\alpha (G) \ge n^{5/12-o(1)}\).

By the aforementioned observation, this actually gives the same improved bound for the first half of the range for any instance with \(k=4,\) i.e. for \(3r-2\le m \le 3.5(r-1)\).

To prove an upper bound on the minimum possible \(\alpha (G)\) among all graphs with \(\alpha _m(G)\ge r\), one needs to find a graph which has small independence number while having big independent sets spread around everywhere. Given the close relation of our problem to Ramsey numbers, random graphs are natural candidates for such examples. A binomial random graph \({\mathcal {G}}(n,p)\) is an n-vertex graph in which we include every possible edge independently with probability p. Understanding \(\alpha _m(G)\) in \(G \sim {\mathcal {G}}(n,p)\) turns out to be an interesting problem in its own right. Observe that the requirement \(\alpha _m(G)\ge r\) may be rephrased as stating that G contains no copy of an m-vertex graph H with \(\alpha (H)\le r-1\) as a subgraph. A standard application of Lovász local lemma tells us that if we are only forbidding a single graph H, then the largest p we can take is controlled by the 2-density of H (see Sect. 3 for the definition of 2-density and more details). If we are instead forbidding a family of graphs the correct parameter turns out to be the minimum of the 2-densities over all graphs in our family. This reduces our problem to the following natural extremal question, which we propose to study. What is the minimum value of the 2-density of an m-vertex graph H with \(\alpha (H) \le r-1\)? If we denote the answer to this question by M(m, r) the above discussion leads us to the following reduction.

Proposition 1.4

Let m, r be fixed, \(m \ge 2r-1 \ge 3\) and \(M=M(m,r)\). Then for any n there exists an n-vertex graph G with \(\alpha _m(G)\ge r\) and \(\alpha (G) \le n^{1/M+o(1)}\).

The value of M(m, r), and hence also our upper bounds for the local to global independence number problem, are mostly controlled by the same parameter \(k=\lceil {\frac{m}{r-1}} \rceil \) as before. Some intuition behind this, suggested by Linial and Rabinovich [30], is that a natural example of an m vertex graph with independence number at most \(r-1\) is a vertex disjoint union of \(r-1\) cliques with sizes as equal as possible (in other words complement of a Turán graph on m vertices with no clique of size r). This graph clearly has no independent set of size r and we picked the clique sizes as equal as possible in order to minimise the 2-density. Our parameter k is simply the size of a largest clique in this example.

Turning to the results, we start once again with the range \(2r-1\le m\le 3r-3\), i.e. \(k=3\). Here Linial and Rabinovich show that there exist n-vertex graphs G satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\) and \(\alpha (G) \le n^{1-1/(8r-4)}.\) We improve the exponent in this bound for the whole range. Moreover, the improvement in the exponent is by a constant factor independent of r, towards the end of the range.

Proposition 1.5

Let \(m\ge 2r-1 \ge 3,\) for any n there exists an n-vertex graph G satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\) with \(\alpha (G) \le n^{1-\frac{1}{2r-2}+o(1)}\) and if \(m\ge 3r-4>2\) with \(\alpha (G) \le n^{\frac{3}{5}+\frac{2}{5r-13}+o(1)}.\)

These bounds follow from our results on \(M(2r-1,r)\), which we determine precisely and \(M(3r-4,r)\) which we determine up to lower order terms. This means that in terms of using random graphs as examples, these bounds are essentially best possible for \(m=2r-1,3r-4\). We can obtain a constant factor improvement in the exponent for about 1/3 of the range, but since we believe our current argument does not give the best possible answer, in terms of M(m, r), for the whole range we leave this open for future research.

The problem of determining \(M(3r-4,r)\) is closely related to a well-studied problem of finding large independent sets in sparse triangle-free graphs. Perhaps the most famous result in this direction is due to Ajtai–Komlós–Szemerédi [1] and Shearer [34], but for our problem earlier results of Staton [35] and Jones [21] turn out to be more relevant. These results are part of a very active research area of studying graphs having no cliques of size k nor independent sets of size r but which have potentially much fewer vertices than the corresponding Ramsey number R(k, r). Our problem of lower bounding M(m, r) falls under this framework since we can always assume that our graphs, in addition to having no independent sets of size r, are also \(K_k\)-free or the 2-density is already large. We point the interested reader to classical papers [2, 35] and numerous papers citing them.

We now turn to the general case of \(k \ge 4\). Let us begin with the initial instance, so when \(r=3\). Unfortunately, here the results for \(r=3\) do not immediately generalise as they did in the case of lower bounds. They do however provide a starting point, which serves as a basis for more general results. Here we determine M(m, 3) precisely for all m, which allows us to improve exponents in the previously best bounds of Linial and Rabinovich [30]. They showed there are n-vertex graphs G with \(\alpha _m(G) \ge 3\) and \(\alpha (G) \le n^{\frac{4+o(1)}{m-4/(m-2)}}\) if m is even, and \(\alpha (G) \le n^{\frac{4+o(1)}{m-3/(m-2)}}\) if m is odd.

Theorem 1.6

For any n there exists an n-vertex graph G satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge 3\) with \(\alpha (G) \le n^{\frac{4+o(1)}{m+2}}\) if m is even, and \(\alpha (G) \le n^{\frac{4+o(1)}{m+3-13/\sqrt{m}}}\) when \(m \ge 5\) is odd (here both terms \(o(1)\rightarrow 0\) as \(n\rightarrow \infty )\).

We remark that in the even case any improvement of our exponent, in terms of m, provably leads to improvement over the best-known lower bounds on Ramsey numbers and in the odd case without improving the Ramsey numbers one can only improve the term \(13/\sqrt{m}\).

Once again our arguments in this particular regime show that the problem of determining M(m, r) is related to yet another well-studied problem. Namely, the stability problem for Turán’s theorem first considered by Erdős, Győri and Simonovits in [16]. While one can use their results to obtain good bounds on M(m, 3) obtaining precise answers requires a different, more careful argument.

In the fully general case we determine M(m, r) up to lower order terms (where r is considered fixed and m large), giving us the following result.

Theorem 1.7

Let us assume m is sufficiently larger than r and set \(k=\lceil {\frac{m}{r-1}} \rceil \). Then there exists \(c_r>0\) such that for any n there exists an n-vertex graph G satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\) with \(\alpha (G) \le n^{\frac{2+o(1)}{k+1-{c_r}/{\sqrt{k}}}}\).

This improves previous upper bounds of Linial and Rabinovich from roughly \(n^{\frac{2}{k-1}}\) to roughly \(n^{\frac{2}{k+1}}\) and is once again essentially best possible assuming lower bounds on Ramsey numbers are tight.

While the above result requires m to be large compared to r some of our ideas apply for any choice of the parameters. To illustrate this we consider the case \(m=20,r=5\) which was used by various researchers as a benchmark to compare their methods. Here Linial and Rabinovich show there are graphs G having \(\alpha _{20}(G) \ge 5\) and \(\alpha (G) \le n^{18/39+o(1)}.\) Krivelevich [26] improved this to \(\alpha (G) \le n^{14/33+o(1)}.\) He obtains this as an application of his result on the minimum number of edges in colour-critical graphs. The best possible bound using this approach was later obtained by Kostochka and Jancey [24] who showed \(\alpha (G) \le n^{18/43+o(1)}\). For comparison \(39/18\approx 2.17, 33/14 \approx 2.36\) and \(43/18\approx 2.39,\) while our methods allow us to improve this to 3. That is, there exists a graph G with \(\alpha _{20}(G)\ge 5\) which has \(\alpha (G) \le n^{1/3+o(1)}\) and once again this is best possible (up to the o(1) term) without improving the lower bounds on Ramsey numbers R(5, s).

In addition to the above applications and connections, another reason which makes the study of M(m, r) interesting is its relation to a random graph process. For a graph property \({\mathcal {P}}\) the random graph process with respect to \({\mathcal {P}}\) starts with an empty graph and iteratively adds a new uniformly random edge for as long as this does not violate \({\mathcal {P}}\). Random graph processes have been extensively studied for a variety of properties and have found numerous applications (see e.g. [7, 8, 17, 22, 27, 32] and references therein). In our setting M(m, r) controls the final density of the random process with respect to the m-local r-independence property \(\alpha _m \ge r\). So M(m, r) essentially controls the behaviour of this random process.

Organisation. We will prove our lower bound results in Sect. 2. We start this section by proving Proposition 1.1. We continue by formalising in the form of Lemma 2.1 the above-mentioned reduction of our general lower bound result, Theorem 1.2, to the case \(r = 3\). We then focus on this case in Sect. 2.1 to complete the proof of Theorem 1.2. In Sect. 2.2 we prove our stronger bound in the \((m,r)=(7,3)\) case raised by Erdős and Hajanl, namely Theorem 1.3. In Sect. 3 we prove our upper bound results. We begin by proving our reduction to the 2-density Turán problem, namely Proposition 1.4. We then switch the focus to proving our results concerning this 2-density Turán problem in Sect. 3.1. We begin by proving our results in the triangle-free regime in Sect. 3.1.1 providing us with a proof of Proposition 1.5. In Sect. 3.1.2 to solve the independence number two case which provides us with a proof of Theorem 1.6. We complete the section with our asymptotic solution to the general problem which gives a proof of Theorem 1.7. In Sect. 4 we give some concluding remarks and open problems as well as the summary of our results. We also include three appendices. In Appendix A we prove a slight modification of a result of [21] which we need in the proof of the second part of Proposition 1.5. In Appendix B we completely solve a benchmark case \((m,r)=(20,5)\) of the Turán 2-density problem. Finally, in Appendix A we prove some upper bounds for the Turán 2-density problem which establish the tightness of our results in this direction but are not necessary for our reduction to the local to global independence number problem.

Notation. We will denote by |G| the number of vertices in G and by e(G) the number of edges in G. For \(v \in G\) we denote by N(v) the neighbourhood of v and by \(d(v)=|N(v)|\) its degree in G. For \(S\subseteq G\) we denote the induced subgraph of G on this subset by G[S]. Whenever working with graphs satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\) all our asymptotics are with respect to \(n=|G|\) and we treat m and r as constants unless otherwise specified. When working with directed graphs \(N^{\pm }(v)\) denotes the in/out neighbourhood of v and \(d^{\pm }(v)\) in/out degree.

2 Lifting the Lower Bounds from Local to Global Independence Number

In this section, we prove our lower bounds on \(\alpha (G)\) for a graph G satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\). We begin with our lower bound result for \(k=\lceil {\frac{m}{r-1}} \rceil =3\), namely Proposition 1.1.

Proposition 1.1

Let \(m=2r-2+t\) for \(1 \le t \le r-1\). Then any n-vertex graph G satisfying \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\) has \(\alpha (G) \ge \Omega (n^{1-1/\ell }),\) where \(\ell =\lfloor {\frac{r-1}{t}} \rfloor +1\).

Proof

Let us first assume we can find a vertex disjoint collection of \(a=t\ell -(r-1)\) cycles \(C_{2\ell -1}\) and \(t-a\) cycles \(C_{2\ell +1}\). Their union makes a subgraph of G of order \(a(2\ell -1)+(t-a)(2\ell +1)=(2\ell +1)t-2a=2r-2+t=m\) and has no independent set of size larger than \(a(\ell -1)+(t-a)\ell =t\ell -a=r-1\). This gives us a contradiction to \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\), which means such a union does not exist in G.

If we can find a cycles \(C_{2\ell -1}\) in G, then the remainder of the graph can not contain \(t-a\) cycles \(C_{2\ell +1}\), this means that by removing at most m vertices from G we can find a subgraph which is \(C_{2\ell +1}\)-free. If there are fewer than a cycles \(C_{2\ell -1}\) in G, then we find a subgraph, again with at least \(n-m\) vertices which is \(C_{2\ell -1}\)-free. In either case, a classical result from [15] (see also [28, 36] for slight improvements) on cycle-complete Ramsey numbers tells us there is an independent set of size at least \(\Omega ((n-m)^{1-1/\ell })=\Omega (n^{1-1/\ell }),\) as desired. \(\square \)

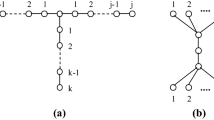

We now show how to generalise any improvement made in the \(r=3\) case to half of the range for any k. It will be convenient to denote by f(n, m, r) the smallest possible size of \(\alpha (G)\) in an n vertex graph with \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\).

Lemma 2.1

Let \(k=\lceil {\frac{m}{r-1}} \rceil \) and \(\ell =m-(k-1)(r-1)\). Provided \(\ell \le \frac{r-1}{2}\) we have \(f(n,m,r) \ge \min \{f(n-m,2k-1,3),f(n-m,k-1,2)\}\).

Proof

Let G be a graph on n vertices with \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\). Let us first assume that we can find a vertex disjoint union consisting of \(\ell \) subgraphs on \(2k-1\) vertices, each having no independent set of size 3, and \(r-1-2\ell \) copies of \(K_{k-1}\). This union is a subgraph on \(\ell (2k-1)+(r-1-2\ell )(k-1)=(r-1)(k-1)+\ell =m\) vertices which has no independent set larger than \(2\ell +r-1-2\ell =r-1\), contradicting \(\alpha _m(G) \ge r\).

If we can find \(\ell \) such subgraphs on \(2k-1\) vertices this means that the remainder of the graph can not contain \(r-1-2\ell \) copies of \(K_{k-1}\). Removing our subgraphs and a maximal collection of \(K_{k-1}\)’s in the remainder we obtain a subgraph on at least \(n-m\) vertices which is \(K_{k-1}\)-free, or in other words has \(\alpha _{k-1} \ge 2\) implying \(f(n,m,r) \ge f(n-m,k-1,2)\). If there are fewer than \(\ell \) such subgraphs we may remove a maximal collection and obtain a subgraph on at least \(n-m\) vertices which contains no subgraphs on \(2k-1\) vertices without an independent set of size 3. In other words, our new subgraph has \(\alpha _{2k-1} \ge 3\) so \(f(n,m,r) \ge f(n-m,2k-1,3)\) as claimed. \(\square \)

Note that \(f(n,k-1,2)\ge \alpha \) is equivalent to \(R(k-1,\alpha ) \le n\) implying that the best known bound is

This represents a natural barrier for our results since it seems very likely that \(f(n,2k-1,3)\ge f(n,k-1,2)\). On the other hand, the results of [30] and [4] may be stated as \(f(n,m,r) \ge f(n-m,k,2)\). Therefore, obtaining a lower bound for \(f(n,2k-1,3)\), better than f(n, k, 2), immediately improves their bound whenever the above lemma applies, i.e. \(\ell \le \frac{r-1}{2}\). Our result in the next section gives a bound which is halfway (in terms of exponents) between the above bounds coming from Ramsey numbers of \(K_{k-1}\) and \(K_k\) vs large independent set.

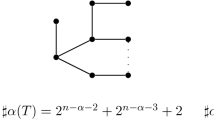

2.1 Independent Sets of Size Three Everywhere

In this subsection, we will show how to find big independent sets in graphs satisfying \(\alpha _{2k-1}(G) \ge 3\). This is inherently a Ramsey question in the following sense. How big a graph do we need to take in order to guarantee that we can find an independent set of size \(\alpha \) or a subgraph H with \(2k-1\) vertices and no independent set of size 3? The approach of [30] and [4] is to always look for a single graph H, namely a vertex disjoint union of \(K_k\) and \(K_{k-1}\). This H clearly has no independent set of size 3 and the approach further reduces to finding a copy of \(K_k\). The reason is that any bound strong enough to guarantee the existence of a \(K_k\) will remain strong enough to force a \(K_{k-1}\) once we remove the k vertices of a single copy of \(K_k\), and thus force a copy of H. Our key new ingredient is to in addition look for a different \(2k-1\)-vertex graph which we call \(H_{2k-1}\) and define to be a blow-up of \(C_5\) with parts of sizes \(1,k-2,1,1,k-2\) appearing in that order around the cycle, with cliques placed inside of parts (see Fig. 1 for an illustration). Since the complement of this graph is an actual blow-up of \(C_5\) it is triangle-free, implying that \(H_{2k-1}\) has no independent set of size 3 and is hence forbidden in any graph satisfying \(\alpha _{2k-1}(G) \ge 3\).

We start by explaining the general idea behind our argument. As argued above our goal is to find a large independent set in an arbitrary \(K_k\)-free and \(H_{2k-1}\)-free n-vertex graph G. We will do so by finding a vertex v and a large collection of vertex disjoint \(K_{k-1}\)’s with \(k-2\) vertices inside N(v). We know that the remaining vertex of any such \(K_{k-1}\) lies outside N(v) as our graph is \(K_k\)-free. Furthermore, we know that the set of these last vertices spans an independent set as otherwise any edge between such vertices together with their \(K_{k-1}\)’s and v make a copy of \(H_{2k-1}\) (see Fig. 2 for an illustration). This gives us our desired large independent set.

The more difficult part of the argument is to actually find such a collection of \(K_{k-1}\)’s. The following two easy lemmas will help us control how many \(K_{k-1}\)’s we can find with \(k-2\) vertices inside a neighbourhood of v and how many such \(K_{k-1}\)’s can intersect another one, respectively. Let us denote by \(t_i(G)\) the number of copies of \(K_i\) in G, (we omit G when it is clear from context).

Lemma 2.2

Let G be a graph with \(\alpha (G) \le \alpha \) and let \(k \ge 2.\) Provided \(t_{k-1}(G)>0,\) we have

Proof

We will prove the claim by induction on k. For the base case of \(k=2\) (note that \(t_1=|G|\)) the claim follows from Turán’s theorem which gives \(e(G) \ge \frac{n^2}{2 \alpha }-\frac{n}{2}\) (see [3]). Let us now assume \(k \ge 3\) and that the claim holds for \(k-1\). Given \(S\subseteq V(G)\) let us denote by e(S) the number of edges with both endpoints in the common neighbourhood of S and by d(S) the number of common neighbours of S. Then we have

Where we used Turan’s theorem within the common neighbourhood of S in the first inequality and the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality for the second. Dividing by \((k-1)t_{k-1}/2\) and using the induction assumption we obtain

\(\square \)

Lemma 2.3

Let G be a \(K_k\)-free graph with \(\alpha (G) < \alpha \). Then for any \(i \le k\) we have

Proof

We prove the claim by induction on i. For the base case of \(i=1\) the claim is equivalent to \(t_1=|G| \le \alpha ^{k-1}\) which holds by the classical bound on the Ramsey number \(R(k,\alpha )\). Let us now assume the claim holds for \(i-1\). Given a subset of vertices S we denote by N(S) the set of common neighbours of S and by \(d(S)=|N(S)|\). If \(G[S]=K_{i-1},\) then N(S) is \(K_{k-i+1}\)-free in addition to having no independent set of size \(\alpha \). So the same classical bound on Ramsey numbers as above implies \(d(S) \le \alpha ^{k-i}\). Taking a sum and using the inductive assumption we obtain:

\(\square \)

We are now ready to prove our general result for \(r=3\).

Proof of Theorem 1.2

The main part of the proof will be to show that \(f(n,2k-1,3)\ge \Omega (n^{1/(k-3/2)})\) but let us first verify this establishes the theorem in full generality. Indeed assuming this holds, given \(k=\lceil {\frac{m}{r-1}} \rceil \) and \(m \le (k-\frac{1}{2})(r-1)\) we have \(m-(k-1)(r-1) \le \frac{r-1}{2}\) so that we may apply Lemma 2.1 giving us, when combined with (1), the desired result:

Our remaining task now is to show that in an n-vertex graph G which contains an independent set of size 3 among any \(2k-1\) vertices we can find an independent set of size \(\alpha =\Omega (n^{1/(k-3/2)})\). With this choice of \(\alpha \), we may assume that \(n \ge C \alpha ^{k-3/2}\) for an arbitrarily large constant C. Since the result for \(k=3\) holds by Proposition 1.1 we may assume \(k \ge 4\).

As discussed above if G contains a \(K_k\), then the remainder of the graph has no \(K_{k-1}\), so by the classical Ramsey bound we get \(\alpha (G) \ge (n-k)^{1/(k-2)} \ge \Omega (n^{1/(k-3/2)})\). So we may assume G is \(K_k\)-free. Our goal is to find a vertex v and a collection \({\mathcal {M}}\) of \(\alpha \) vertex disjoint \(K_{k-1}\)’s each with \(k-2\) vertices in N(v). Then as we already explained above, any such \(K_{k-1}\) has exactly one vertex outside N(v), as our graph is \(K_k\)-free. These vertices outside of N(v) form an independent set as otherwise any edge between such vertices together with their \(K_{k-1}\)’s and v make a copy of \(H_{2k-1}\), a contradiction. In order to do so we will analyse common neighbourhoods of cliques of size \(k-3\) inside N(v). Any edge we find inside such a common neighbourhood gives rise to a copy of \(K_{k-1}\) and if we find there a path of length 2 starting with v, then the last edge of this path gives rise to a copy of \(K_{k-1}\) with exactly \(k-2\) vertices in N(v), which we are looking for.

Let us first give a lower bound on \(T:=(k-2)t_{k-2}\) (recall that \(t_{k-2}\) denotes the number of \(K_{k-2}\)’s in G) which counts extensions of a \(K_{k-3}\) into a \(K_{k-2}\), i.e. the sum of sizes of common neighbourhoods of \(K_{k-3}\)’s in our graph. By a simple application of Lemma 2.2 we get:

where in the second inequality we used \(n\ge 2k\alpha ^{k-3},\) which holds for our choice of \(\alpha \). Using Lemma 2.2 repeatedly in a similar way we get the following lower bound on T which will be useful later in the argument.

In order to carry out the above proof strategy, for every clique of size \(k-3\) we are going to restrict our attention only to a large part of its common neighbourhood where independent sets expand (meaning they have many vertices adjacent to some vertex of the set). This will achieve our goal since G being \(K_k\)-free means that the common neighbourhood of a \(K_{k-3}\) is triangle-free, so the part of this common neighbourhood inside N(v) is an independent set. Hence, expansion of this particular independent set precisely means there are many endpoints of a path of length 2 starting with v, giving many choices for a \(K_{k-1}\) with \(k-2\) vertices in N(v).

To obtain such an expansion we are going to first restrict attention to \(K_{k-3}\)’s which have the common neighbourhood of order at least half the average which equals \(T/t_{k-3}\). We will call such a \(K_{k-3}\) typical and we know that altogether there are at least T/2 ways of extending typical \(K_{k-3}\)’s into a \(K_{k-2}\). By (2), any typical \(K_{k-3}\) has a common neighbourhood of size at least \(d:= n/(4\alpha ^{k-3})\).

We now proceed to obtain independent set expansion inside the common neighbourhood of each typical \(K_{k-3}\). Let S be such a \(K_{k-3}\). Let X be a maximal independent set inside of the common neighbourhood N of S which has fewer than \(\frac{d-2\alpha }{2\alpha } \cdot |X|\) neighbours inside N, in case no such sets exists we set \(X=\emptyset \). We now remove X and all its neighbours from N. Since X is an independent set we know \(|X|\le \alpha \) so we have removed at most \(\alpha +\frac{d-2\alpha }{2\alpha }\cdot \alpha = \frac{d}{2}\) vertices from N. Any remaining vertex in N is called an expanding neighbour of S. Since S was arbitrary, every typical \(K_{k-3}\) has at least d/2 expanding neighbours and inside its expanding neighbourhood independent sets expand by a factor of \(\frac{d-2\alpha }{2\alpha } \ge \frac{d}{4\alpha }=\frac{n}{16\alpha ^{k-2}}=:d'\). In particular, every vertex in N (being an independent set of size one) has degree at least \(d'\) in this set. Furthermore, there are still at least T/4 ways to extend a typical \(K_{k-3}\) into a \(K_{k-2}\) using an expanding neighbour.

We now pick our v to be a vertex which is an expanding neighbour of \(g_v \ge T/(4n)\) typical \(K_{k-3}\)’s (such v exists by double counting and the above bound). Let \({\mathcal {S}}\) denote the collection consisting of all such \(K_{k-3}\)’s. Let us first observe some properties of an \(S \in {\mathcal {S}}\). We denote by \(N_S\) its expanding neighbourhood and by \(D_S:=N(v) \cap N_S\) the set of its expanding neighbours inside N(v). By definition, \(v \in N_S\) for all \(S \in {\mathcal {S}}\). Also, as was explained above, we know that v has at least \(d'\) neighbours within \(N_S\), i.e. \(|D_S| \ge d'\). These neighbours span an independent set (since they belong to the common neighbourhood of \(k-2\) vertices in \(v \cup S\)) of size at least \(d'\), so they expand inside \(N_S\). This gives us \(d'^2\) different vertices which together with S and one of the vertices in \(D_S\) make a \(K_{k-1}\) with exactly \(k-2\) vertices inside N(v). To find many such disjoint \(K_{k-1}\)’s we will use the fact that there are in total \(\sum _{S \in {\mathcal {S}}} |D_S| \ge g_v \cdot d'\) ways to extend \(K_{k-3}\)’s in \({\mathcal {S}}\) into a \(K_{k-2}\) using an expanding neighbour belonging to N(v).

Let us now consider a maximal collection \({\mathcal {M}}\) of vertex disjoint \(K_{k-1}\)’s each with exactly \(k-2\) vertices inside N(v). Let us assume towards a contradiction that \(|{\mathcal {M}}| < \alpha \). We will show below that if \(|{\mathcal {M}}| < \alpha ,\) we can still find some \(S \in {\mathcal {S}}\) and a set \(D_S' \subseteq D_S\) of at least \(d'/2\) of its expanding neighbours in N(v) such that both S and \(D'_S\) are vertex disjoint from all cliques in \({\mathcal {M}}\). For now, suppose we found such S and \(D_S'\). Since \(D_S'\subseteq D_S\) is an independent set (as we explained above), it expands within the neighbourhood of S meaning that there are at least \(d'^2/2=\frac{n^2}{2^9\alpha ^{2k-4}} \ge \alpha \) vertices which together with S and some vertex in \(D_S'\) make a \(K_{k-1}\) with \(k-2\) vertices in N(v). Moreover, note that all these \(d'^2/2\) vertices lie outside of N(v) or we get a \(K_k\) in G. Since we removed fewer than \(\alpha \) vertices outside of N(v) (recall that each \(K_{k-1} \in {\mathcal {M}}\) has exactly one vertex outside N(v)) one of these vertices is disjoint from all cliques in \({\mathcal {M}}\) and gives rise to the desired copy of \(K_{k-1}\), which is vertex disjoint from any clique in \({\mathcal {M}}\) (since both S and \(D_S'\) are chosen disjoint from any clique in \({\mathcal {M}}\)) and hence contradicts its maximality.

Therefore, it remains to be shown that there is an \(S \in {\mathcal {S}}\) and \(d'/2\) of its expanding neighbours inside N(v), all disjoint from any clique in \({\mathcal {M}}\). Note that cliques in \({\mathcal {M}}\) cover at most \(\alpha (k-2)\) vertices inside N(v). On the other hand note that any vertex \(u\in N(v)\) can belong to at most \(\alpha ^{\left( {\begin{array}{c}k-2\\ 2\end{array}}\right) }/(k-3)!\) copies of \(K_{k-2}\) inside N(v). This follows from Lemma 2.3 since any such copy of \(K_{k-2}\) amounts to a copy of \(K_{k-3}\) in the common neighbourhood of v and u which spans a \(K_{k-2}\)-free graph with no independent set of size \(\alpha \) (or we are done). On the other hand, any \(K_{k-2}\) can be an extension of at most \(k-2\) different copies of \(K_{k-3}\) in \({\mathcal {S}}\) so there are at least \(g_v d'-\alpha ^{\left( {\begin{array}{c}k-2\\ 2\end{array}}\right) +1}(k-2)^2/(k-3)!\) extensions of a \(K_{k-3}\) from \({\mathcal {S}}\) to a \(K_{k-2}\) inside N(v) both disjoint from any clique in \({\mathcal {M}}\). Note that

where in the first inequality we used \(g_v \ge T/(4n)\) and (3) to bound T, while in the last inequality we used that \(n \ge C\alpha ^{k-3/2} \ge C\alpha ^{k-2+1/(k-2)}.\) This means that there are at least \(g_vd'/2\) such extensions and since \(g_v=|{\mathcal {S}}|\) there must be a \(K_{k-3}\) with \(d'/2\) extensions, as desired. \(\square \)

2.2 The Erdos–Hajnal (7,3) Case

For \(k=4\) the result from the previous section implies that graphs with \(\alpha _7 \ge 3\) have \(\alpha \ge \Omega (n^{2/5})\) which already suffices to confirm the conjecture of Erdős and Hajnal [12]. In this section, we show how to further improve this bound to \(\alpha \ge n^{5/12-o(1)}\), i.e. we prove Theorem 1.3.

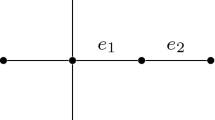

The general idea will be similar as in the previous subsection. Here since \(k=4\) we may assume our G satisfying \(\alpha _7(G)\ge 3\) is \(K_4\) and \(H_7\)-free. In fact, in this case, \(\alpha _7(G) \ge 3\) is essentially (up to removal of a few vertices) equivalent to G being \(K_4\) and \(H_7\)-free. Since we do not need the non-obvious direction here, we prove it as Lemma 3.6 in the following section where it will be useful.

Unlike in the previous section, since the desired \(\alpha \) is bigger we will not be able to find a large enough set of vertex disjoint triangles (not containing v) with an edge in N(v). However, these triangles will still play a major role in the argument. We will call them v-triangles and the vertex of a v-triangle not in N(v) is going to be called a v-extending vertex (in other words any non-neighbour of v which belongs to a \(K_4\) minus an edge together with v). While we can not find a large enough collection of disjoint v-triangles the fact our graph is \(H_7\)-free imposes many restrictions on the subgraph induced by v-extending vertices, which we call \(N_{\triangle }(v)\). The following lemma establishes the properties of \(N_{\triangle }(v)\) that we will use in our argument.

Lemma 2.4

Let G be a \(K_4\) and \(H_7\)-free graph and \(v \in G\). Then

-

(a)

\(N_{\triangle }(v) \cap N(v) = \emptyset \).

-

(b)

If \(u,w \in N_{\triangle }(v)\) belong to vertex disjoint v-triangles, then \(u \not \sim w.\)

-

(c)

\(N_{\triangle }(v)\) is triangle-free.

-

(d)

Let C be a connected subgraph of \(N_{\triangle }(v)\) consisting only of vertices belonging to at least 5 different v-triangles. If \(|C| \ge 2,\) then there exists \(u\in N(v)\) such that for any \(w\in C,\) all the edges within \(N(v) \cap N(w)\) make a star centred at u in G.

Proof

Part (a) is immediate since G is \(K_4\)-free and part (b) since it is \(H_7\)-free.

For part (c) assume to the contrary that there is a triangle x, y, z in \(N_{\triangle }(v)\) and that f, g, h are edges in N(v) completing a v-triangle with x, y, z respectively. By part (b) any two of f, g, h need to intersect. This is only possible if they make a triangle, in which case together with v they make a \(K_4\), or if they make a star, in which case the centre of the star together with x, y, z makes a \(K_4\), either way we obtain a contradiction.

For part (d) let \(u,w \in N_{\triangle }(v)\) be adjacent and belong to at least 5 different v-triangles. We claim that then edges within \((N(w) \cap N(v)) \cup (N(u) \cap N(v))\) make a star in G. Indeed if \(N(u)\cap N(v)\) would contain two disjoint edges, then by part (b) any edge in \(N(w) \cap N(v)\), of which there are at least 5 by assumption, must intersect them both. Since there can be at most 4 edges which intersect both of the two disjoint edges, we conclude there can be no disjoint edges in \(N(u)\cap N(v)\). This means that the edges span either a star or a triangle. Since there are at least 5 edges, the former must occur. We can repeat for w in place of u and observe that the only way for each pair of edges, one per star, to intersect is that they share the centre, as claimed. Propagating along any path in C we deduce that the same holds for any pair of vertices in C. \(\square \)

The following corollary, based mostly on part d) of the above lemma, allows us to partition \(N_\triangle (v)\) into three parts which we will deal with separately in our argument.

Corollary 2.5

Let G be a \(K_4\) and \(H_7\)-free graph and \(v \in G\). Then there exists a partition of \(N_\triangle (v)\) into three sets L, I and C with the following properties:

-

(a)

L consists only of vertices belonging to at most 4 different v-triangles.

-

(b)

I is an independent set.

-

(c)

C can be further partitioned into \(C_1,\ldots , C_m\) such that there are no edges between different \(C_i\)’s and for every \(C_i\) there is a distinct \(v_i \in N(v)\) such that any v-triangle containing a vertex from \(C_i\) must contain \(v_i\) as well.

Proof

We chose L to consist of all v-extending vertices belonging to at most 4 v-triangles. We chose I to consist of isolated vertices in \(G[N_{\triangle }(v) \setminus L]\) and \(C=N_{\triangle }(v) \setminus (L \cup I)\). Note that C is a union of connected components of \(G[N_{\triangle }(v) \setminus L]\), which we denote by \(C_1',C_2',\ldots \) each of order at least 2 and consisting entirely of vertices belonging to at least 5 different v-triangles. In particular, Lemma 2.4 part d) implies that there exists a vertex \(v_i'\in N(v)\) such that any v-triangle containing a vertex from \(C_i'\) must also contain \(v_i'\). Finally, we merge any \(C_i'\)s which have the same vertex for their \(v_i'\) to obtain the desired partition \(C_1,\ldots , C_m\) of C. \(\square \)

We are now ready to prove Theorem 1.3.

Proof of Theorem 1.3

Let G be an n-vertex graph with \(\alpha _7(G) \ge 3\). Our task is to show it has an independent set of size \(\alpha =n^{5/12-o(1)}.\) If G contains a \(K_4\) the remainder of the graph must be triangle-free so has an independent set of size \(\Omega (\sqrt{n})>\alpha \). Hence, we may assume G is \(K_4\)-free as well as \(H_7\)-free.

We begin by ensuring the minimum degree is high, so that we can ensure good independent set expansion inside neighbourhoods. We repeatedly remove any vertex with degree at most \(2n/\alpha .\) Observe that if we remove more than half of the vertices, then the removed vertices induce a subgraph with at least n/2 vertices and at most \(n\cdot {2n}/{\alpha }\) edges. So, Turán’s theorem implies there is an independent set of size at least \(\frac{n/2}{8n/\alpha +1}\ge \Omega (\alpha )\) and we are done. Let us hence assume that G has minimum degree at least \(2n/\alpha \) (we technically need to pass to a subgraph on at least n/2 vertices but this only impacts the constants).

Let us fix a vertex v. Let X be a maximal independent set inside N(v) which has fewer than \(n/\alpha ^2 \cdot |X|\) neighbours inside N(v), and we set \(X=\emptyset \) if such a set does not exist. Since X is independent we may assume it has size at most \(\alpha /2\) so \(|X|+|N(X) \cap N(v)| \le \alpha /2+n/\alpha ^2\cdot \alpha /2 \le n/\alpha \). We directFootnote 1 all edges from v towards \(N(v)\setminus (X \cup N(X))\). Note that \(d^+(v) \ge d(v)/2\ge n/\alpha \) and inside \(N^+(v)\) independent sets expand by at least a factor of \(x:=n/\alpha ^2\ge \Omega (n^{2/12})\). We repeat for every vertex v, and note that some edges of G might be assigned both directions, while some other edges none.

Our first goal is to show there are in total many v-triangles for which their edge in N(v) belongs to \(N^{-}(v)\) and the remaining two edges of the triangle are directed away from this edge. We will call such a v-triangle a directed v-triangle. In other words, we are counting the number of \(K_4\)’s minus an edge with the 4 edges incident to the missing edge all being directed towards vertices of the missing edge. We denote this count by \(T_4\).

Claim

Unless \(\alpha (G) \ge \Omega (n^{5/12})\) we have \(T_4 \ge \Omega (n^2).\)

Proof

We will show that for any vertex v with in-degree at least half the average we get at least \(\Omega (d^-(v)^2/n^{2/12})\) directed v-triangles. Let us for now assume this holds. Note that v with lower in-degree contribute at most half to the value of \(\sum _{v \in G} d^{-}(v)=\sum _{v \in G} d^{+}(v) \ge n^2/\alpha \ge \Omega (n^{19/12})\) (recall that \(d^{+}(v) \ge n/\alpha \)). An application of Cauchy–Schwarz implies there are at least \(\Omega ((\sum _{v \in G} d^{-}(v))^2/n \cdot n^{-2/12})\ge \Omega (n^2)\) directed triangles.

Let us now fix a vertex v with in-degree at least half the average, this in particular means \(d^{-}(v) \ge n/(2\alpha )\ge n^{7/12}\). We know that any vertex \(u\in N^{-}(v)\) has v as an out-neighbour which means that v, as a single vertex independent set, expands inside \(N^{+}(u)\). So v has at least x neighbours inside \(N^+(u),\) i.e. u has at least x out-neighbours inside N(v). Since u was an arbitrary vertex in \(N^{-}(v)\) this means there are at least \(d^{-}(v)x\ge \Omega (n^{9/12})\) edges inside N(v) which are directed away from a vertex in \(N^{-}(v)\) (note that if an edge of G has both directions and is inside of \(N^{-}(v),\) then it is counted twice and considered as 2 directed edges). Let us call the set of such directed edges M, so in particular \(|M| \ge d^{-}(v)x \ge \Omega (n^{9/12})\). Note further that given such a directed edge \(uw \in M\), since u has w as a single vertex independent set in its out-neighbourhood w expands there. This means that our edge lies in at least x v-triangles with both edges incident to u directed away from u. We call the third vertex of any such triangle uw-extending, note that it belongs to \(N_{\triangle }(v)\). We are now going to assign types to edges in M according to where, inside \(N_\triangle (v)\), we find the majority of their extending vertices.

Let us fix a partition of \(N_\triangle (v)\) into C, L and I, provided by Corollary 2.5. Given a directed edge \(uw \in M\) we say it is of type L or C if it has at least x/3 extending neighbours in L or C, respectively. We say it is of type I if it was not yet assigned a type. In particular, an edge of type I also has at least x/3 extending vertices in I (since we have shown above it has at least x in total), but we also know it has at most 2x/3 extending vertices in other parts of \(N_\triangle (v)\).

First case: at least a third of the edges in M are of type C.

Any vertex in N(v) is adjacent to fewer than \(\alpha \) other vertices inside N(v) (since these vertices make an independent set as G is \(K_4\)-free). This means there is a matching \(M'\) of at least \(|M|/(6\alpha )\) edges of type C, as otherwise, vertices making a maximal matching are incident to fewer than |M|/3 edges so it can be extended. Let us denote by \(N_e\) the set of extending vertices of an edge \(e\in M'\) inside C. By assumption, \(|N_e|\ge x/3\) and note that each \(N_e\) spans an independent set (being in a common neighbourhood of e). On the other hand, we also claim \(N_e\)’s are disjoint. To see this suppose \(x \in N_e \cap N_{e'}\) for two distinct edges \(e,e' \in M'\). By definition of \(N_e\), there is some i such that \(x \in C_i\) and by Corollary 2.5 part c) we know that \(v_i \in e\) and \(v_i \in e'\), a contradiction. Note also that there can be no edges between distinct \(N_e,N_{e'}\) or we find an \(H_7\). This means that \(\bigcup _{e \in M'} N_e\) is an independent set of size at least \(x/3 \cdot |M|/(6\alpha )=\Omega (n^{6/12}).\)

Second case: at least a third of the edges in M are of type L.

Since any vertex in L belongs to at most 4 distinct v-triangles it can in particular be an extending vertex of at most 4 edges from M. Since every edge of type L has at least x/3 extending vertices in L this means \(|L| \ge x|M|/12 \ge n^{11/12}/12\). Now, Lemma 2.4 part c) implies \(L\subseteq N_{\triangle }(v)\) is triangle-free so there is an independent set of size at least \(\sqrt{|L|} \ge \Omega (n^{5.5/12}).\)

Third case: at least a third of the edges in M are of type I.

Let \(u \in N^{-}(v)\). Let us denote by \(T_u\) the set of out-neighbours of u which together with u make an edge of type I. We know by the case assumption that \(\sum _{u \in N^{-}(v)} |T_u| \ge |M|/3\). Note that \(T_u\subseteq N(v) \cap N^{+}(u)\) so must span an independent set (or we find a \(K_4\) in G) and hence expands inside \(N^{+}(u)\). This means there are at least \(x|T_u|\) distinct vertices extending an out-edge of u of type I. Note however that we do not know that all of them must be in I. But since any edge of type I has at most 2x/3 extending neighbours outside of I this means that there are least \(x|T_u|/3\) vertices in I extending an out-edge of u. This in particular means that u sends at least \(x|T_u|/3\) edges directed towards I. By taking the sum over all u we obtain that the number of edges directed from \(N^{-}(v)\) to I is at least \(xM/9 \ge d^{-}(v)x^2/9 \ge \Omega (n^{11/12})\).

Since I spans an independent set we may assume \(|I| < \alpha \). Let \(S_u=N^{-}(v) \cap N^{-}(u)\) for any \(u\in I\). Let \(s_u=|S_u|\) so we know that \(\sum _{u \in I} s_u \ge d^{-}(v)x^2/9\ge \Omega (n^{11/12})\). Let \(I'\) be the subset of I consisting of vertices u with \(s_u\ge 2\alpha \). Since vertices of \(I {\setminus } I'\) contribute at most \(2|I|\alpha <n^{10/12}\) to the above sum, we still have \(\sum _{u \in I'} s_u \ge d^{-}(v)x^2/18.\) By Turán’s theorem for any \(u \in I'\) there needs to be at least \(s_u^2/(4\alpha )\) (using that \(s_u \ge 2\alpha \)) edges inside \(S_u\), or we find an independent set of size \(\alpha \). Each such edge gives rise to a directed v-triangle. Hence, using Cauchy–Schwarz, there are at least \(\sum _{u \in I'} {s_u^2}/{(4\alpha )} \ge \Omega (d^-(v)^2x^4/\alpha ^2)\ge \Omega (d^-(v)^2/n^{2/12})\) directed v-triangles, as desired. \(\square \)

Let us give some intuition on how we are going to use the fact that \(T_4\) is big. Let us denote by \(\overrightarrow{d_e}\) the number of common out-neighbours of vertices making an edge e. Recall that \(T_4\) can be interpreted as the number of \(K_4\)’s minus an edge with all its edges oriented towards the missing edge. We call the remaining edge (for which we are not insisting on the direction) the spine. Note that the number of our \(K_4\)’s minus an edge having some fixed edge e as the spine is precisely \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}\overrightarrow{d_e}\\ 2\end{array}}\right) \). This means that \(T_4=\sum _{e \in E(G)} \left( {\begin{array}{c}\overrightarrow{d_e}\\ 2\end{array}}\right) .\) Our bound on \(T_4\) obtained above tells us that in a certain average sense the \(\overrightarrow{d_e}\)’s should be big.

Observe now that if one finds a star centred at v consisting of s edges each with \(\overrightarrow{d_e} \ge t,\) then this means that the s leaves each have t out-neighbours inside N(v) (note that we are disregarding the information that they are in fact inside \(N^{+}(v)\)). This will allow us to play a similar game as we did in the previous claim, indeed there we tackled the same problem with \(s=d^{-}(v)\) and \(t=x\) (which we obtained through expansion) with an important difference, namely that the star was in-directed. The bound on \(T_4\) tells us that there is such a star with larger (in certain sense) parameters s and t and the next claim shows how this gives rise to many of our \(K_4\)’s minus an edge, which we find in a different place (in particular they do not use the centre of the star since we do not know the direction of centre’s edges).

For any \(v \in G\) let \(S_v\) be the star consisting of a centre v and all its edges in G. Let us also denote by \(s_v\) the total number of our \(K_4\)’s minus an edge with an edge of \(S_v\) as their spine, i.e. \(s_v=\sum _{e \in S_v} \left( {\begin{array}{c}\overrightarrow{d_e}\\ 2\end{array}}\right) \). Summing over v we also have \(2T_4=\sum _{v}\sum _{e \in S_v} \left( {\begin{array}{c}\overrightarrow{d_e}\\ 2\end{array}}\right) =\sum _{v} s_v\).

Claim

Unless \(\alpha (G) \ge n^{5/12-o(1)}\) and provided \(s_v \ge \frac{T_4}{n}\) there exist \(\frac{s_v^2}{n^{7/12+o(1)}}\) of our \(K_4\)’s minus an edge with their spine inside N(v).

Proof

Let us first “regularise” \(\overrightarrow{d_e}\)’s for \(e \in S_v\). Let us partition these edges into at most \(\log n\) sets with all edges belonging to a single set having \(\overrightarrow{d_e} \in [t,2t]\) for some t. Since \(s_v=\sum _{e \in S_v} \left( {\begin{array}{c}\overrightarrow{d_e}\\ 2\end{array}}\right) \) and the edges in \(S_v\) are split into at most \(\log n\) sets, we conclude that one set contributes at least \(\frac{s_v}{\log n}\) to this sum. I.e. edges in this set make a substar S of \(S_v\) consisting of s edges, each having \(t \le \overrightarrow{d_e} \le 2t\) for some s, t satisfying \(2st^2 \ge s\left( {\begin{array}{c}2t\\ 2\end{array}}\right) \ge \frac{s_v}{\log n} \ge \frac{T_4}{n\log n} \ge n^{1-o(1)}\).Footnote 2 We may assume that \(t \le n^{5/12}\) since \(\overrightarrow{d_e}\) counts certain common neighbours of a fixed edge which must span an independent set (or there is a \(K_4\)).

Similarly, as in the previous claim, we define M to be the set of directed edges inside N(v) with source vertex being a leaf of S. Now the fact that any edge \(e \in S\) has \(\overrightarrow{d_e} \ge t\) means that any leaf u of S is a source of at least t edges in M. Let us remove all but exactly t such edges from M, so, in particular, \(|M|=st\) (as before while some edges might be oriented both ways we treat this as two distinct directed edges). Let us denote by \(T_u\) the set of t out-neighbours of u which together with u make an edge in M. We know \(T_u\) is an independent set (it consists of common neighbours of the edge vu). In particular, both \(T_u\) and any of its subsets expand inside \(N^{+}(u)\). Let us consider an auxiliary bipartite graph with the left part being \(T_u\) and the right part being \(N_\triangle (v)\cap N^{+}(u)\). We put an edge between two vertices if together with u they make a triangle in G. The expansion property translates to the fact that any subset of size \(t'\) of the left part has at least \(t'x\) distinct neighbours on the right. A standard application of Hall’s theorem (to the graph obtained by taking x copies of every vertex on the left) tells us we can find t disjoint stars each of size x in this graph. Translating back to our graph, for each of the t edges incident to u in M we have found a set of x out-neighbours of u which extend it into a triangle. Moreover, these sets are disjoint for distinct edges. We call these x vertices extending for the corresponding edge.Footnote 3

Once again let us take a C, L, I partition provided by Corollary 2.5 and assign types C, L and I to edges in M, which have at least x/3 extending neighbours in C, L and I, respectively. This is similar to the previous argument except that we are using our new, slightly modified definition of extending vertices. We again split into three cases according to which type is in the majority.

First case: at least st/3 edges in M are of type C.

As in 1. case of the previous claim we can find a matching \({\mathcal {M}}\) of at least \(st/(6\alpha )\) edges of type C (since vertices of \({\mathcal {M}}\) are incident to at most \(2|{\mathcal {M}}|\alpha \) edges inside N(v)). Let us denote by \(N_e\) the set of extending neighbours of an edge \(e \in {\mathcal {M}}\) inside C, so \(|N_e| \ge x/3\). Again, as before, each \(N_e\) is independent (neighbours of the same edge), and they are disjoint for different e (otherwise if a vertex belonging to two \(N_e\)’s belongs to \(C_i,\) we get a contradiction to the uniqueness of \(v_i\)) and there are no edges between distinct \(N_e\)’s (or we find an \(H_7\)). So their union makes an independent set of size at least \(stx/(18\alpha )\). If \(t \le n^{4/12},\) then \(st^2 \ge n^{1-o(1)}\) implies \(st \ge n^{8/12-o(1)}\) and our independent set is of size at least \(n^{5/12-o(1)}\), as desired. So let us assume \(t \ge n^{4/12}.\)

Note that by Corollary 2.5, given an edge \(e\in M\) and its extending neighbour which belongs to some \(C_i\) we know that \(v_i \in e\) and \(v_i\) can be either source or sink of e. In the former case, we say the neighbour is source-extending and in the latter sink-extending. We say e is of type C-source if it has at least x/6 source-extending neighbours in C and of type C-sink if it has at least x/6 sink-extending neighbours in C.

If there are at least st/6 edges in M of type C-sink that means there is a leaf u of S which is a startpoint of at least t/6 such edges. If uw is one of these t/6 edges it has a set of at least x/6 sink-extending neighbours which span an independent set (being common neighbours of an edge) and all belong to the same \(C_i\) (namely the one for which \(v_i=w\)) and these \(C_i\)’s are distinct between edges. This means that these sets are disjoint between ones corresponding to distinct edges and span an independent set (there are no edges between distinct \(C_i\)’s) so we found an independent set of size at least \(tx/36 \ge \Omega (n^{6/12})\).

If there are at least st/6 edges in M of type C-source we need to be able to find s/12 leaves of S incident to at least t/12 such edges each (since we know that every leaf of S is incident to exactly t edges in M so otherwise, there would be fewer than \(s/12 \cdot t + s \cdot t/12=st/6\) such edges in total). For any such leaf u this means we find \(\frac{t}{12} \cdot \frac{x}{6} \ge \frac{tx}{72}\) source-extending neighbours of its edges (using our preprocessing fact that extending neighbours of distinct edges incident to u are disjoint). By Lemma 2.4 c) we know there is an independent set of size \(\sqrt{tx}/9\) among these neighbours. Since these are source-extending neighbours we know they all belong to \(C_i\) for which \(v_i=u\). In particular, for distinct u they belong to distinct \(C_i\)’s, meaning we obtain an independent set of size \(\Omega (s\sqrt{tx}) =\Omega (st^2 \sqrt{x}/t^{3/2})\ge n^{13/12-o(1)}/t^{3/2} \ge n^{5.5/12-o(1)},\) using \(t \le n^{5/12}\).

Second case: at least st/3 edges in M are of type L.

Let us first assume \(s \ge t\). We again find a matching of size \(st/(6\alpha )\) of edges of type L in M. Each edge e in the matching gives rise to a set \(N_e\) of x/3 extending neighbours in L. \(N_e\) spans an independent set (being inside the common neighbourhood of an edge) and there can be no edges between distinct \(N_e\)’s (or we find an \(H_7\)). This means that the union of \(N_e\)’s spans an independent set. Since any extending neighbour in this union can be extending for at most 4 edges (so belongs to at most 4 different \(N_e\)’s) this gives \(\alpha (G) \ge stx/(72\alpha ) \ge (st^2)^{2/3}x/(72\alpha ) \ge n^{5/12-o(1)},\) using \(s \ge t\) and \(st^2 \ge n^{1-o(1)}\).

Let us now assume \(t \ge s\). We can find at least s/6 leaves of S each being a start vertex of at least t/6 edges in M of type L (otherwise there would be fewer than \(s/6 \cdot t+ s \cdot t/6=st/3\) edges in total). Given a directed edge \(uw \in M\) of type L, with u being one of these s/6 leaves, we define \(A_{uw}\) as the set of extending vertices of uw belonging to L. We will now state some properties of these sets \(A_{uw},\) which will allow us to find a big independent set. Since this is the most technical part of the proof and, once the appropriate properties are identified, is independent of the rest of the argument we prove it as a separate lemma afterwards.

- (1):

-

No vertex belongs to more than 4 different \(A_{uw}\)’s. Since \(A_{uw} \subseteq L\) and by Corollary 2.5 part (a), any vertex in L belongs to at most 4 different v-triangles, this means it can belong to at most 4 different \(A_{uw}\)’s.

- (2):

-

\(|A_{uw}| \le x\). This follows since, by our definition, there are exactly x uw-extending vertices.

- (3):

-

\(\sum _{w}|A_{uw}| \ge tx/18\). This follows since for any u there are at least t/6 edges uw for which \(A_{uw}\) is defined and each such edge being of type L means there are at least x/3 extending vertices, meaning \(|A_{uw}| \ge x/3\).

- (4):

-

If uw and \(u'w'\) are independent, then there can be no edges between \(A_{uw}\) and \(A_{u'w'}\). Else, we find \(H_7\).

This precisely establishes the conditions of Lemma 2.6, which provides us with an independent set of size \(\min (\Omega (s\sqrt{tx}),\Omega (s^{1/2}t^{3/4}x^{1/4}), \Omega (s^{3/5}t^{3/5}x^{2/5}))\). Each of the three expressions is minimised when t is as large as possible (under the assumption \(st^2 \ge n^{1-o(1)}\)) so we may plug in \(t=n^{5/12}\) and \(s=n^{2/12-o(1)}\) in which case the first expression evaluates to \(n^{5.5/12-o(1)},\) the second to \(n^{5.25/12-o(1)}\) and the third to \(n^{5/12-o(1)}\).

Third case: there are at least st/3 edges in M of type I.

Since I spans an independent set we know \(|I| < \alpha \). Any directed edge uw in M of type I has at least x/3 extending neighbours in I. Since these are distinct for different w’s by our definition of an extending neighbour and since we insist that extending neighbours are out-neighbours of u this means that overall there are at least stx/9 edges directed from leaves of S to I.

This means that the average out-degree from S to I is at least tx/9. This together with a standard application of Cauchy–Schwarz implies there are \(\Omega (s(tx)^2)=n^{16/12-o(1)}\) (recall that \(st^2 \ge s_v/(2\log n) \ge n^{1-o(1)}\)) out-directed cherries (\(K_{1,2}\)’s) with the centre in S. If we denote by \({\mathcal {P}}\) the set of pairs of vertices in I, then \(|{\mathcal {P}}|=\left( {\begin{array}{c}|I|\\ 2\end{array}}\right) \le \alpha ^2\), let us also denote by \(d_p\) the number of common in-neighbours of a pair of vertices \(p \in {\mathcal {P}}\). So in particular, \(\sum _{p \in {\mathcal {P}}} d_p =\Omega (s(tx)^2)=n^{16/12-o(1)}\). Pairs p with \(d_p<2\alpha \) contribute at most \(|{\mathcal {P}}|\cdot 2\alpha \le n^{15/12-o(1)}\) to this sum so if \({\mathcal {P}}'\subseteq {\mathcal {P}}\) denotes the set of pairs which have \(d_p \ge 2\alpha ,\) then also \(\sum _{p \in {\mathcal {P}}'} d_p =\Omega (s(tx)^2)=n^{16/12-o(1)}\). Applying Turán’s theorem inside a common neighbourhood of \(p \in {\mathcal {P}}'\) we find there \(d_p^2/(4\alpha )\) edges (using that \(d_p \ge 2\alpha \)) or there is an independent set of size \(\alpha \). Note that any edge we find inside this common in-neighbourhood gives rise to our desired \(K_4\) minus an edge. In particular, using Cauchy–Schwarz we find at least \(\sum _{p \in {\mathcal {P}}'} \frac{d_p^2}{4\alpha } \ge \frac{(\sum _{p \in {\mathcal {P}}'} d_p)^2}{4\alpha |{\mathcal {P}}'|} \ge \Omega (s^2(tx)^4/\alpha ^3)\ge s_v^2/n^{7/12+o(1)}\) copies of our desired \(K_4\) minus an edge, as claimed. \(\square \)

Recall that \(2T_4 = \sum _{v} s_v\). Note also that stars with \(s_v \ge T_4/n\) contribute at least \(T_4\) to this sum. Hence, taking the sum over v of the number of copies of our \(K_4\)’s minus an edge with the spine in N(v) we obtain at least \(\sum s_v^2/ n^{7/12+o(1)} \ge T_4^2/n^{19/12+o(1)} \ge T_4 n^{5/12-o(1)},\) where we used Cauchy–Schwarz in the first inequality and our bound \(T_4 \ge \Omega (n^{2})\), from the first claim in the second. Note however that certain copies of our \(K_4\)’s minus an edge got counted multiple times. But, for every v that counted our \(K_4\) minus an edge, we know it had its spine inside N(v). This means that a single copy could be counted at most \(\alpha (G)\) times since the spine (being an edge in G) can have at most \(\alpha (G)\) neighbours, as they span an independent set. In particular, unless \(\alpha (G) \ge n^{5/12-o(1)}\), this shows that there are more than \(T_4\) distinct copies of our \(K_4\)’s minus an edge, contradicting the definition of \(T_4\) and completing the proof. \(\square \)

We now prove the lemma we used in the proof above. Let us first attempt to help the reader parse the statement. It says that if we can partition vertices of G into a grid of subsets each of size at most x (so each cell of the grid contains at most x vertices), such that G only has edges between vertices in the same row or column of the grid, and we additionally know that there is a large number of vertices in each row, then we can find a big independent set in the whole graph.

Lemma 2.6

Let G be a triangle-free graph with vertex set \(\bigcup _{i,j} A_{ij}\) where \(i \in [s], j \in {\mathbb {N}}\). If

-

1.

no vertex appears in more than 4 different \(A_{ij}\)’s;

-

2.

\(|A_{ij}| \le x,\) for any i, j;

-

3.

for some \(t\ge s\) and any \(i \in [s]\) there are at least tx vertices in \(\cup _{j} A_{ij}\);

-

4.

there are no edges of G between \(A_{ij}\) and \(A_{k\ell }\) for any \(i \ne k\) and \(j \ne \ell ,\)

then \(\alpha (G) \ge \min (\Omega (s\sqrt{tx}),\Omega (s^{1/2}t^{3/4}x^{1/4}), \Omega (s^{3/5}t^{3/5}x^{2/5}))\).

Proof

Let us first replace any vertex which appears in multiple \(A_{ij}\)’s with distinct copies of itself, one per \(A_{ij}\) it appears in. Our new graph has all \(A_{ij}\) disjoint and satisfies the same conditions as the original. In addition, the independence number went up by at most a factor of 4 so showing the result for our new graph implies it for the original. So let us assume that sets \(A_{ij}\) actually partition the vertex set of G.

Let \(\alpha =\alpha (G)\). We will call \(\cup _{j} A_{ij}\) a row of our grid, \(\cup _{i} A_{ij}\) a column and each \(A_{ij}\) a cell. Let us first clean up the graph a bit. As long as we can find an independent set I of size more than \(2\alpha /s\) using vertices from at most t/s cells inside some row, we take I, delete the rest of the row and all the columns containing a vertex of I from G. If we repeat this at least s/2 many times we obtain an independent set of size larger than \(\alpha \) which is impossible. This means that upon deleting at most s/2 many rows and at most \((t/s) \cdot s/2=t/2\) many columns we obtain a subgraph for which in any row any t/s cells don’t contain an independent set of size at least \(2\alpha /s\). This subgraph still satisfies all the conditions of the lemma with \(t:=t/2\) and \(s:=s/2\). The only non-immediate condition is 3, it holds since we deleted at most t/2 cells in any of the remaining rows, so in total at most tx/2 vertices in that row altogether, using that any cell contains at most x vertices. From now on we assume our graph G satisfies the property that in any row any t/s cells don’t contain an independent set of size \(2\alpha /s\)

Let us delete vertices from our graph until we have exactly tx in every row. Let n denote the number of vertices of G, so \(n =stx\). Observe that at least half of the vertices of G have degree at least \(n/(4\alpha )\) as otherwise, vertices with degree lower than this induce a subgraph which has an independent set of size at least \(\alpha \) by Turán’s theorem. Condition 4 ensures each such vertex either has at least \(n/(8\alpha )\) neighbours in its row or \(n/(8\alpha )\) neighbours in its column. In particular, at least a quarter of vertices of G fall under one of these cases. Since G is triangle-free, the neighbourhood of any vertex is an independent set. We conclude that either there are at least s/4 rows containing an independent set of size \(n/(8\alpha )\) or there are t/4 columns containing an independent set of size \(n/(8\alpha )\).

Let us first consider the latter case. Let U be the union of our t/4 independent sets of size at least \(n/(8\alpha )\), belonging to distinct columns, so consisting of at least \(tn/(32\alpha )\) vertices. Let \(a_i\) denote the number of vertices of U in row i. Then \(\sum _{i=1}^{s} a_i \ge tn/(32\alpha )\) and each \(a_i \le tx\) (since we removed all but tx vertices in any row). On the other hand, since G is triangle-free, we know that in each row we can find an independent subset of U of size \(\sqrt{a_i}\). In particular, since U was constructed as a union of independent sets in columns (and all edges of G are either within columns or within rows) this means that U contains an independent set of size \(\sum _{i=1}^{s} \sqrt{a_i} \ge \frac{tn}{32\alpha \cdot tx} \cdot \sqrt{tx}=\Omega (st^{3/2}x^{1/2}/\alpha )\) (where we used \(n=stx\) and the standard fact that sum of roots is minimised, subject to constant sum, when as many terms as possible are as large as possible). In other words, we showed \(\alpha \ge \Omega (st^{3/2}x^{1/2}/\alpha )\) giving us the second term of the minimum.

Moving to the former case let us again take a union U of our s/4 independent sets of size at least \(n/(8\alpha )\), belonging to distinct rows, so again \(|U| \ge sn/(32\alpha )\). Call a cell \(A_{ij}\) full if it contains at least \(4\alpha /t\) vertices of U. There are fewer than t/(2s) full cells in any row since otherwise, U restricted to \(\lceil {t/(2s)} \rceil \) full cells gives us an independent set of size at least \(2\alpha /s\) using at most \(\lceil {t/(2\,s)} \rceil \le t/s\) cells (using \(t \ge s\)), which contradicts our property from the beginning. Using this and once again the property from the beginning we conclude there can be at most \(2\alpha /s\) vertices of U in full cells of any fixed row. If \(2\alpha /s\ge n/(16\alpha ),\) then \(\alpha ^2 \ge \Omega (ns) \ge \Omega (s^2tx),\) so first term of the minimum is satisfied. So we may assume \(2\alpha /s\le n/(16\alpha )\). Hence, by removing from U any vertex belonging to a full cell we remove at most half the vertices of U (since U had at least \(n/(8\alpha )\) vertices in every row). Now, finally, denote by \(a_i\) the number of vertices of U belonging to the column i. So \(\sum _{i=1}^{s} a_i = |U| \ge sn/(64\alpha )\) and \(a_i \le s \cdot 4\alpha /t\), since all the remaining vertices of U belong to non-full cell. As before \(\alpha \ge \sum _{i=1}^{s} \sqrt{a_i} \ge \frac{sn/(64\alpha )}{{4\,s\alpha /t}} \cdot \sqrt{4\,s\alpha /t}\ge \Omega (s^{3/2}t^{3/2}x/\alpha ^{3/2})\) giving us the third term of the minimum. \(\square \)

3 2-Density and Local Independence Number

In this section, we show our upper bounds on the minimum possible \(\alpha (G)\) in a graph G satisfying \(\alpha _m(G)\ge r\). To do this we need to exhibit a graph with no large independent set in which any m-vertex subgraph contains an independent set of size r. As discussed in the introduction the natural candidates are random graphs and the answer is controlled by M(m, r) which is defined to be the minimum value of the 2-density over all graphs H on m vertices having \(\alpha (H) \le r-1.\) It will be convenient to define \(d_2(H)=\frac{e(H)-1}{|H|-2},\) so that the 2-density is defined as the maximum of \(d_2(H')\) over subgraphs \(H'\) of order at least 3, from now on whenever we consider 2-density we will implicitly assume the subgraphs we take to have at least 3 vertices. We begin by proving our reduction to the 2-density Turán problem, namely Proposition 1.4.

Proposition 1.4

Let m, r be fixed, \(m \ge 2r-1 \ge 3\) and \(M=M(m,r)\). Then for any n there exists an n-vertex graph G with \(\alpha _m(G)\ge r\) and \(\alpha (G) \le n^{1/M+o(1)}\).

Proof

A graph H is said to be strictly 2-balanced if \(m_2(H)>m_2(H')\) for any proper subgraph \(H'\) of H. I.e., if H itself is the maximiser of \(d_2(H)\) among its subgraphs and in particular \(m_2(H)=d_2(H)=\frac{e(H)-1}{|H|-2}\).

Let \({\mathcal {H}}=\{H_1,\ldots , H_t\}\) be a collection of strictly 2-balanced graphs such that any m-vertex H with \(\alpha (H) \le r-1\) contains some \(H_i\) as a subgraph. We can trivially obtain it by replacing any H in our family which is not strictly 2-balanced by its subgraph \(H'\) which maximises \(d_2(H').\) In particular, \({\mathcal {H}}\) is a family of strictly balanced 2-graphs H satisfying \(m_2(H)=d_2(H)\ge M,\) with at most m vertices and with the property that if a graph is \({\mathcal {H}}\)-free, then it satisfies \(\alpha _m \ge r\). Note that \(t\le 2^{\left( {\begin{array}{c}m\\ 2\end{array}}\right) },\) so is in particular bounded by a constant (depending on m).

Let \(G \sim {\mathcal {G}}(n,p),\) where we choose \(p:=1/(48tn^{1/M})\) and will be assuming n to be large enough throughout. Let \(A_K\) denote the event that a subset \(K \subseteq V(G)\), consisting of \(k:=\frac{8\log n}{p}+2=O(n^{1/M}\log n)\) vertices, spans an independent set. In particular, we have \({\mathbb {P}}(A_k)=(1-p)^{\left( {\begin{array}{c}k\\ 2\end{array}}\right) }\). Let \(B_j^{i}\) denote the event that we find a copy of \(H_i\) at the j-th possible location (so fixing the subset of vertices of G where we could find \(H_i\) and the labellings of vertices). In particular, \({\mathbb {P}}(B_j^i)=p^{e(H_i)}.\) Our goal is to show that with positive probability none of the events \(A_K\) or \(B_j^i\) occur, which implies that there is an \({\mathcal {H}}\)-free graph with no independent set of size \(O(n^{1/M}\log n)\) as desired. We will do so by using the asymmetric version of the Lovász local lemma (see Lemma 5.1.1 in [3]). To apply the lemma we first need to understand how many dependencies there are between different types of events. In particular, given \(A_K\) it depends only on \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}k\\ 2\end{array}}\right) \) edges of G, so in particular it is mutually independent of all events \(B_{i}^j\) which do not contain one of these edges. In particular, it is mutually independent from all but at most \( k^2 n^{|H_i|-2}\) events \(B_{i}^j\) and at most \(n^k\) other events \(A_{K'}\) (since there are at most this many such events in total). Similarly, any \(B_j^i\) is mutually independent of all but at most \(e(H_i)n^{|H_{i'}|-2}\le m^2n^{|H_{i'}|-2}\) events \(B_j^{i'}\) for a fixed \(i'\) and at most \(n^k\) events \(A_k\).

We now need to choose parameters x (corresponding to events of type \(A_K\)) and \(y_i\) (corresponding to events of type \(B_i^j\)) such that

which will complete the proof. We choose \(x=1/n^k\) so that in particular \((1-x)^{n^k} \ge 1/3\) (as n is large) and \(y_i=p/(8tn^{|H_i|-2}) \le 1/2\) so that in particular \((1-y_i)^{n^{|H_i|-2}} \ge e^{-p/(4t)}\) (using \(1-a \ge e^{-2a}\) for \(a \le 1/2\)). With these choices we obtain

Here, in the second inequality, we used the fact that m is a constant while \(p \rightarrow 0\) so \(m^2p \rightarrow 0\) and in particular \(e^{-m^2p/4} \le 1/2\) (since n is large). In the third inequality we used \(n^{-\frac{|H_i|-2}{e(H_i)-1}} \ge n^{-\frac{1}{M}},\) which follows since M is equal to the minimum of \(\frac{e(H_i)-1}{|H_i|-2}\) over \(H_i\) (and we used \(|H_i| \ge 3\) to put the 48t factor under the exponent). \(\square \)

Remark

This result appears to be the best one can expect to get using random graphs, up to the polylog factor. The polylog factor can likely be slightly improved compared to the above argument by using the \({\mathcal {H}}\)-free process (see e.g. [32] for more details about this process).

If we replace \(m_2(H)\) in the definition of M(m, r) with \(d_2(H)=\frac{e(H)-1}{|H|-2}\) the problem of determining M(m, r) would reduce to the classical Turán’s theorem. Indeed, since the number of vertices is fixed, minimising \(d_2(H)\) is tantamount to minimising the number of edges in an m-vertex graph with \(\alpha (H) <r\) and upon taking complements we reach the setting of the classical Turán’s theorem. This is why it is natural to call our problem of determining M(m, r) the 2-density Turán problem. Note that since \(m_2(H) \ge d_2(H)\) the proposition also holds if we replace M with \(\min d_2(H)\). This essentially recovers the argument of Linial and Rabinovich [30]. However, it turns out one can in many cases do much better by using the actual 2-density.

3.1 The 2-density Turán Problem

In this subsection, we show our results concerning the 2-density Turán problem of determining M(m, r) which together with Proposition 1.4 give upper bounds in the local to global independence number problem mentioned in the introduction.

3.1.1 Triangle-Free Case

Here we show our bounds for the case \(k=3\). This means that m and r satisfy \(2r-1\le m \le 3r-3\) and as expected the behaviour will be very different at the beginning and end of the range. Our first observation determines \(M(2r-1,r)\).

Proposition 3.1

Let \(r \ge 2\). Then \(M(2r-1,r)=m_2(C_{2r-1})=1+\frac{1}{2r-3}.\)

Proof

Since \(C_{2r-1}\) is a \(2r-1\) vertex graph with no independent set of size r we obtain \(M(2r-1,r)\le m_2(C_{2r-1}).\) For the lower bound let G be a graph on \(2r-1\) vertices with \(\alpha (G) \le r-1\), our goal is to show \(m_2(G) \ge m_2(C_{2r-1})\). If G contains a cycle of length \(\ell ,\) then \(m_2(G) \ge m_2(C_\ell ) \ge m_2(C_{2r-1})\) where in the last inequality we used \(\ell \le 2r-1\) since G has only \(2r-1\) vertices. If G contains no cycles it is a forest so in particular it is bipartite. One part of the bipartition must have at least r vertices giving us an independent set of size at least r, which is a contradiction. \(\square \)

Turning to the other end of the range we show.

Theorem 3.2

For \(r \ge 2\) we have \(M(3r-4,r)\ge \frac{5}{3}-\frac{1}{r-2}.\)

Proof

Let G be a graph on \(m=3r-4\) vertices with \(\alpha (G) \le r-1\). If G contains a triangle, then \(m_2(G) \ge 2\) and we are done. If G contains a subgraph \(G'\) on \(m'\) vertices with minimum degree at least 4, then \(m_2(G) \ge d_2(G') \ge \frac{2m'-1}{m'-2}>2\) so again we are done. In particular, we may assume that G is 3-degenerate. These conditions allow us to apply a modification of a result of Jones [21] (see Appendix A for more details about the modification) which tells us that \(e(G) \ge 6\,m-13(r-1)-1=5r-12\). This implies \(m_2(G) \ge d_2(G) \ge \frac{5r-13}{3r-6}= \frac{5}{3}-\frac{1}{r-2}\) as claimed. \(\square \)

This is close to the best possible, for example, the chain graph \(H_r\) (see [21] for more details) has \(3r-4\) vertices, no independent set of size r and \(m_2(H_r)=\frac{5}{3}-\frac{1}{9}\cdot \frac{1}{r-2}\). We believe that as in the problem of [21], these graphs should be optimal, it is not hard to verify that this is indeed the case for the first few values of r and one can improve our result above by repeating more carefully the stability type argument from [21] for our graphs.

In the above result, we did not look at the very end of the range for \(k=3\), namely \(m=3r-3\). The reason is that it seems to behave differently. Of course, \(M(3r-3,r) \ge M(3r-4,r)\) so the same bound as above applies, however, it seems possible that a stronger bound is the actual truth, it is even possible that the answer jumps to \(M(3r-3,r)\ge 2\).

3.1.2 Independence Number Two

In this subsection, we solve the 2-density Turán problem for graphs with no independent sets of size 3. The behaviour depends on the parity of m, we begin with the easier case when m is even.

Lemma 3.3

For any \(k \ge 2\) we have \(M(2k,3) \ge (k+1)/2.\)

Proof

Let G be a graph on 2k vertices with \(\alpha (G)\le 2.\) This condition implies that for any vertex v of G the set of vertices not adjacent to v must span a clique since otherwise, the missing edge together with v makes an independent set in G of size 3. On the other hand, if we can find \(K_k \subseteq G,\) then \(m_2(G) \ge m_2(K_k)=\frac{k+1}{2}\) and we are done. So we may assume G is \(K_k\)-free. Combining these two observations implies every vertex has at most \(k-1\) non-neighbours and in particular \(\delta (G) \ge 2k-1 -(k-1)=k\). This in turn implies \(m_2(G) \ge \frac{e(G)-1}{|G|-2}\ge \frac{k^2-1}{2k-2}=(k+1)/2\) completing the proof. \(\square \)