Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Lateral suspension is an abdominal prosthetic surgical procedure used to correct apical prolapse. The procedure involves the placement of a T-shaped mesh on the anterior vaginal wall and on the isthmus or uterine cervix that is suspended laterally and posteriorly to the abdominal wall. Since its description in the late 90s, modifications of the technique have been described. So far, no consensus on the correct indications, safety, advantages, and disadvantages of this emerging procedure has been reached.

Methods

A modified Delphi process was used to build consensus within a group of 21 international surgeons who are experts in the performance of laparoscopic lateral suspension (LLS). The process was held with a first online round, where the experts expressed their level of agreement on 64 statements on indications, technical features, and other aspects of LLS. A subsequent re-discussion of statements where a threshold of agreement was not reached was held in presence.

Results

The Delphi process allowed the identification of several aspects of LLS that represented areas of agreement by the experts. The experts agreed that LLS is a safe and effective technique to correct apical and anterior prolapse. The experts highlighted several key technical aspects of the procedure, including clinical indications and surgical steps.

Conclusions

This Delphi consensus provides valuable guidance and criteria for the use of LLS in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse, based on expert opinion by large volume surgeons’ experts in the performance of this innovative procedure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Pelvic organs prolapse (POP) affects many women worldwide, causing a significant impact on quality of life [1]. While several transvaginal surgical strategies are available to address this condition, sacral suspension is so far the only transabdominal procedure that has been standardized and thoroughly assessed for safety and efficacy [2]. Based on available evidence, laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (LSCP) is the gold standard for the correction of advanced apical and multicompartmental POP [3].

LSCP is a challenging procedure associated with rare but potentially severe complications. Sacral dissection can expose to accidental injury of the pre-sacral arteries and veins, of the right hypogastric nerve, ureter, and hypogastric artery [4]. A surgical damage of the left common iliac vein is a life-threatening complication that requires advanced skills to be controlled. An additional post-operative complication is a spondylodiscitis linked to the transfixion of the S1–S2 intervertebral disk during the fixation of the mesh to the overlying longitudinal ligament. In addition, LSCP requires deep dissection skills and placement of stitches on difficult-to-access anatomical areas [5]

In the recent past, new abdominal surgical approaches have been developed to correct advanced apical and multicompartmental POP, including pectopexy [6] and laparoscopic lateral suspension (LLS) [7]. These procedures do not involve sacral dissection and are characterized by shorter learning curves, lower intraoperative risks, and seemingly comparable efficacy in correcting apical prolapse. These techniques turn into different anatomical displacements of the apex and of the vaginal walls, which may imply that these procedures might be useful to tailor the correction of specific types and combination pf pelvic floor defects [8].

LLS corrects pelvic organ prolapse using a T-shaped prosthesis that is attached to the apex and the anterior vaginal wall (in some instances also to the posterior vaginal wall). Then, the two arms of the mesh are pulled laterally and posteriorly towards the abdominal wall. LLS preserves vaginal length and width, allowing women to maintain a normal sexual function. LLS is technically less complex compared to LSCP, as it requires less dissection and less stitching and knot-tying, thus, making it more feasible via a minimally invasive approach [9].

Hence, LLS is gaining popularity as an effective and safe surgical approach to address advanced POP, but the surgical technique has not yet been fully standardized, and its specific indications are not well defined [10]

This article stems from a collaboration of a group of expert pelvic floor surgeons with a broad expertise in the use of LLS, with the aim to build consensus though a Delphi process on the technical aspects, indications, benefits, and pitfalls of this innovative procedure.

Laparoscopic lateral suspension: surgical technique

Lateral suspension was first described as an open procedure by Kapandji in 1967 as a colpo-isthmo-cystopexy with transverse strips and later modified and repurposed for laparoscopy by Jean-Bernard Dubuisson in 1997 [11].

LLS is typically performed using a T-shaped mesh. The video demonstrates a step-by-step breakdown of the procedure. The mesh is placed and sutured to the anterior vaginal wall and to the uterine isthmus after dissecting the vesicovaginal space. A sub-peritoneal tunnel is created by inserting a laparoscopic instrument laterally and dorsally on the abdomen, about 3–4 cm above and 3 cm dorsally to the anterior–superior iliac spine. The laparoscopic instrument is pushed to reach the peritoneum and then down to the pelvis under the round ligament, to grasp the lateral arm of the mesh, and to pull it out to the skin through the sub-peritoneal tunnel. This procedure performed bilaterally, on right and left sides, such that a hammock-like structure is formed that suspends the uterus and the vagina to the aponeurosis of the oblique muscles, without tension [12].

Delphi process

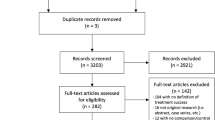

The identification and selection of the candidates to participate to the study took place between December 2022 and January 2023. A comprehensive review of the literature was performed so to identify surgeons who had published in peer-reviewed international journals on LLS. Additional candidates were identified through personal referral from experts. The main criteria for being included was a consistent and continued experience in performing LLS in high volumes. After this step, 28 surgeons were invited to participate to the Delphi project. Six experts declined participation and one did not complete all rounds; thus, the final faculty comprised 21 expert surgeons. The group of experts exhibited heterogeneity in terms of gender and country of origin, as indicated in Table 1. Nearly half of the experts were highly experienced and high-volume surgeons, having performed over 100 surgical procedures annually for more than 10 years in the field of pelvic floor reconstruction, encompassing vaginal, open, LPS, and robotic approaches. All faculty members were proficient in LLS. Half of the experts had been performing LLS surgery for 5–10 years, and all surgeons had over 3 years of experience in pelvic floor reconstructive surgery. Three quarters of the panel performed LSCP on a regular basis.

A scientific committee was formed at the start of the process and consisted of Tommaso Simoncini, Jean Dubuisson, and Friedrich Pauli. The scientific committee was responsible for the generation of 64 statements addressing different aspects of LLS to be submitted to the evaluation of the panel. The statements are reported in Table 2 and are divided into five sub-areas: panel characteristics, indications, surgical technique, particular/complex cases, and post-operative management.

The first round was performed online using the Google Forms application. Each statement was to be scored by the panel’s members based on a 0–10 scale, to indicate the level of agreement or disagreement. A score of 0 indicated total disagreement, while a score of 10 indicated total agreement. The results were analyzed, identifying statements where 70% or more of the group either strongly disagreed (0–3) or strongly agreed (7–10). This resulted in 16 agreements (score 7–10), 5 disagreements (score 0–3), and 33 items where a consensus was not reached (score 4–6), as indicated in Table 2.

A second Delphi round took place in person on May 7th, 2023, in Pisa, Italy. During this round, statements where a trend towards consensus had been reached (60–70% agreement) were reevaluated and resubmitted. As the discussion progressed, new statements emerged, leading to the production of 31 new items that were the panel reached consensus, as indicated in Table 3.

Data statements and informed consent

The data presented in this article consist of voting statements obtained from a Delphi study. Because no patients were enrolled in the study, local ethics committee approval was not required. Informed consent was considered not applicable in this context. However, ethical considerations were an integral part of the study, with emphasis on maintaining process integrity, transparency, and accountability in reporting. The authors, as participants, thoroughly reviewed and accepted the article for submission.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as absolute values and frequency, n (%). All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics v.27 technology (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Indications of LLS

The first set of Delphi statements explored the panel’s opinion on the appropriate surgical indications for LLS. The group agreed that LLS requires less surgical expertise compared to LSCP. Indeed, the experts preferred LLS for hysteropexy over LSCP mostly because of the avoidance of surgical risks associated with promontory dissection.

The experts agreed that LLS is as effective as LSCP in correcting isolated advanced apical prolapse and for the treatment of vaginal vault prolapse. In the presence of vaginal vault prolapse, the experts agreed that LLS can be more effective if performed with a double flap mesh fixed to both the anterior and posterior vaginal wall. Furthermore, while LLS is particularly suitable in cases where patients wish to preserve the uterus, the experts agreed that effective apical suspension with LLS may benefit from supracervical hysterectomy in the presence of a bulky/heavy uterus.

According to the expert panel, LLS can be used as a salvage strategy for managing apical prolapse relapse in patients who have previously undergone LSCP.

From an anatomical standpoint, the panel agreed that the vaginal axis and the position of the apex after LLS is closer to normal anatomy than after LSCP since there is less posterior displacement of the apex. To this extent, experts agreed that they prefer LLS to LSCP to treat combined apical/anterior prolapse as they experience better correction of anterior defects with this technique compared to LSCP. Although they considered LLS not to be the primary option for isolated cystocele, yet they considered it a possible approach for recurrent isolated cystocele.

The panel reached a consensus based on their experience that women with minimal or absent posterior defects treated with LLS do not appear to have a higher incidence of de novo posterior prolapse. However, the panel agreed that LLS may not be suitable for the treatment of multicompartmental prolapse due to limited data on its effectiveness in correcting advanced posterior defects.

Based on experts’ opinion, obesity should not be considered a contraindication for LLS.

Surgical technique

In the second section of the Delphi, the experts' opinions on the technical performance of LLS were examined.

According to the panel, LLS should be performed using a pre-shaped titanized mesh specifically designed for this procedure, as all available data on efficacy and safety are based on this material. The anterior flap of the mesh should be fixed to the anterior vaginal wall in a flat position, utilizing a minimum of 4 fixation points. The use of a vaginal retractor was deemed optimal for performing LLS as it aids in the dissection and exposure of the vesicovaginal septum and of the anterior vaginal wall, ideally to the level of the bladder trigone.

Three quarters of the experts suture the mesh to the anterior vaginal wall using delayed resorbable material (mostly monofilament) or with resorbable tackers, while non-resorbable multifilament material is preferred for suturing the mesh to the uterine cervix and isthmus by most experts.

The panel agreed that the site of the skin incisions for the retroperitoneal tunneling of the mesh is critically important and that it should be located 4 cm above the anterior–superior iliac spine and 3 cm laterally (dorsally) in the absence of pneumoperitoneum. During the retroperitoneal introduction of the grasper and while retracting the mesh arm care should be taken to identify and avoid the gonadal vessels and the external iliac vessels; however, a recent systematic review of the published papers on lateral suspension did not highlight severe complications associated with this surgery or more specifically with this step [10, 13]. The lateral arms of the mesh should be pulled simultaneously after the removal of any vaginal retractor or manipulator to achieve a central position of the apex, and they should be cut at the level of the skin. This provides a suspension that is generally suitable for most patients. The panel agreed that vaginal inspection can be useful to tailor the traction and fixation of the lateral arms of the mesh. The experts concurred that fixation of the prosthesis to the abdominal muscle fascia is not required and should be avoided, as it can cause pain.

Particular cases and surgical skills

In the third section of statements, the experts' opinions on specific surgical cases and surgical skills related to LLS were examined. According to the experts, if an anterior cystocele occurs after LLS, it can be effectively treated transvaginally with anterior colporrhaphy. However, in the case of apical relapse after LLS, the experts recommended an abdominal approach as the first-line treatment. During such re-do abdominal surgeries, the experts agreed that removal the previous mesh material is not mandatory in the absence of mesh-related complications.

Post-operative management

In the fourth and final section of statements, the experts' opinions on the post-operative management of LLS were tested. According to the experts, LLS does not result in a shorter hospitalization period compared to LSCP. The risk of de novo stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is not increased with LLS, and the recovery of urinary function is similar after LLS or LSCP.

Future perspectives

General feelings of the experts were that additional prospective trials focusing on various LLS procedures based on real-life indications should be performed. These trials should aim to evaluate key performance indicators (KPIs) to assess the effectiveness and outcomes of the procedures both with laparoscopic and robotic approaches. The suggested KPIs include POP-Q (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification) measurements at 6 months post-surgery, overall outcomes, complication rates, feasibility, safety, quality of life, sexual function, urinary and bowel function, failure rates, need for re-intervention, timing of complications, and mesh-related complications [14].

By conducting these trials and evaluating these KPIs, the panel thought that valuable data on the performance and impact of LLS could be gathered, hence, obtaining insights into the benefits, risks, and long-term outcomes associated with this procedure and allowing for evidence-based decision-making and further refinement of surgical technique. In addition, the proficiency of surgeons in performing LLS should also be evaluated in these studies to ensure optimal patient outcomes [15].

Discussion

This consensus highlights several important points on the technique and the indications of LLS as a surgical procedure for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse [16].

LLS represents a significant advancement in the field of abdominal POP surgery, offering an alternative to sacral suspension. As with any surgical technique, ongoing research is needed to refine and improve the procedure, to enhance its outcomes, and to delineate better its indications [17].

LSCP is the gold standard for the correction of apical prolapse. However, according to the experts' opinion and to a recent randomized non-inferiority trial, LLS is equally effective to LSCP in correcting apical and anterior prolapse [18].

Thus, LLS is a valuable new tool with growing literature evidence that can be used to treat advanced pelvic organ prolapse. This is particularly important, as it expands the surgical armamentarium and may provide the chance to better tailor the type of suspension (i.e., sacral vs. lateral) based on the type of prolapse [19]. Indeed, based on the experience of the participants to the Delphi process, lateral suspension is more effective in correcting an advanced anterior prolapse compared to sacral suspension. Thus, if this is confirmed with future trials, LLS may not represent a simple alternative to LSCP, but rather a procedure aimed at the preferential treatment of apical/anterior defects, while LSCP may be more appropriate for the management of apical/posterior or three-compartmental prolapses [20].

In addition, mastering LLS allows the management of those rare cases where the sacral promontorium is not accessible or of recurrences or complications of a previous sacrocolpopexy, where a re-do attachment of a mesh to the promontorium is often not feasible or contraindicated (e.g., in the presence of mesh complications).

As a further advantage, the surgical skills required for the performance of LLS are simpler than those needed to perform LSCP, as confirmed by the panel of experts. This results in a quicker acquisition of expertise and in a potential broader diffusion of the procedure, hence in a potential advantage as a valuable and effective surgery might be made available to a broader population [21].

Yet, the experts highlighted through their agreement and discussion how LLS is not a simple procedure and that it requires specific technical attentions. Specifically, a suitable mesh needs to be used and the standard is the titanized, T-shaped polypropylene mesh that has been used to generate the evidence on this procedure [22]. In addition, specific recommendations on the number and type of sutures to secure the mesh were provided by the experts. Finally, the experts deemed critical that the suspension needs to be directed laterally and posteriorly by identifying a specific location to introduce the laparoscopic instrument used to pull the mesh [23].

According to the experts' opinion, in the future, there may be space to explore further a wider range of mesh options that could be used to further tailor lateral suspension, including different lengths and widths of mesh arms, which would allow for greater adaptability to various types of prolapse, and possibly to correct multicompartmental defects [24].

The experts called for randomized controlled trials to compare different surgical approaches for the treatment of POP to consolidate the advantages and disadvantages of each procedure and the appropriate surgical indications [25].

Conclusions

By providing shared expert opinion and recommendations based on common experience, the committee aimed to provide other pelvic surgeons with valuable information on the role, the safety, and the strengths and pitfalls of LLS compared to the current gold standard, LSCP [26, 27]. Based on this consensus, LLS emerges as a suitable, safe, and effective procedure to treat advanced apical prolapse that requires attention and further clinical development to fully understand its surgical place in the treatment of pelvic floor defects.

Abbreviations

- PFRS:

-

Pelvic floor reconstructive surgery

- PF:

-

Pelvic floor

- POP:

-

Pelvic organ prolapse

- LLS:

-

Laparoscopic lateral suspension

- LSCP:

-

Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy

References

Veit-Rubin N, Dubuisson JB, Gayet-Ageron A et al (2017) Patient satisfaction after laparoscopic lateral suspension with mesh for pelvic organ prolapse: outcome report of a continuous series of 417 patients. Int Urogynecol J 28:1685–1693. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00192-017-3327-2

Chen YH, Wang L, Wang YN, Sun L (2023) Laparoscopic lateral abdominal-wall suspension combined with anterior vaginal-wall folding for the pelvic organ prolapse. Asian J Surg 46:3001–3002. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ASJSUR.2023.02.027

Maher CF, Feiner B, Decuyper EM et al (2011) Laparoscopic sacral colpopexy versus total vaginal mesh for vaginal vault prolapse: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 204:360.e1-360.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AJOG.2010.11.016

Barbato G, Rollo S, Borri A et al (2021) Laparoscopic vaginal lateral suspension: technical aspects and initial experience. Minerva Surg 76:245–251. https://doi.org/10.23736/S2724-5691.20.08414-X

Rice NT, Hu Y, Slaughter JC, Ward RM (2013) Pelvic mesh complications in women before and after the 2011 FDA public health notification. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 19:333–338. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0B013E3182A330C1

Bolovis D, Hitzl W, Brucker C (2022) Robotic mesh-supported pectopexy for pelvic organ prolapse: expanding the options of pelvic floor repair. J Robot Surg 16:815–823. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11701-021-01303-7

Dubuisson JB, Veit-Rubin N, Wenger JM, Dubuisson J (2017) La suspension latérale cœlioscopique, une autre façon de traiter les prolapsus génitaux. Gynécologie Obstétrique Fertilité & Sénologie 45:32–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GOFS.2016.12.009

Pulatoğlu Ç, Yassa M, Turan G et al (2021) Vaginal axis on MRI after laparoscopic lateral mesh suspension surgery: a controlled study. Int Urogynecol J 32:851–858. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00192-020-04596-8

Chatziioannidou K, Veit-Rubin N, Dällenbach P (2022) Laparoscopic lateral suspension for anterior and apical prolapse: a prospective cohort with standardized technique. Int Urogynecol J 33:319–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-04784-0

Campagna G, Vacca L, Panico G et al (2021) Laparoscopic lateral suspension for pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 264:318–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJOGRB.2021.07.044

Kapandji M (1967) Treatment of urogenital prolapse by colpo-isthmo-cystopexy with transverse strip and crossed, multiple layer, ligamento-peritoneal douglasorrhaphy. Ann Chir 21:321–328

Miele GM, Marra PM, Cefalì K et al (2021) A new combined laparoscopic-vaginal lateral suspension procedure for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Urology 149:263. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.UROLOGY.2020.12.010

Borruto F, Chasen ST, Chervenak FA, Fedele L (1999) The Vecchietti procedure for surgical treatment of vaginal agenesis: comparison of laparoscopy and laparotomy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 64:153–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7292(98)00244-6

Hsee L, Devaud M, Civil I (2012) Key performance indicators in an acute surgical unit: have we made an impact? World J Surg 36:2335–2340. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00268-012-1670-5

Mellett C, O’Donovan A, Hayes C (2020) The development of outcome key performance indicators for systemic anti-cancer therapy using a modified Delphi method. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). https://doi.org/10.1111/ECC.13240

Geoffrion R, Larouche M (2021) Guideline no. 413: surgical management of apical pelvic organ prolapse in women. J Obstetr Gynaecol Can 43:511–523.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOGC.2021.02.001

Okada Y, Hayashi T, Sawada Y et al (2019) Laparoscopic lateral suspension for pelvic organ prolapse in a case with difficulty in performing laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. IJU Case Rep 2:118–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/IJU5.12051

Russo E, Montt Guevara MM, Sacinti KG et al (2023) Minimal invasive abdominal sacral colpopexy and abdominal lateral suspension: a prospective, open-label, multicenter, non-inferiority trial. J Clin Med 12:2926. https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM12082926

Tagliaferri V, Taccaliti C, Romano F et al (2022) Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy versus pelvic organ prolapse suspension for surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse: a retrospective study. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore) 42:2075–2081. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2021.2021508

Campagna G, Panico G, Caramazza D et al (2019) Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy plus ventral rectopexy for multicompartment pelvic organ prolapse. Tech Coloproctol 23:179–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10151-019-01940-Z/FIGURES/3

Dubuisson JB, Eperon I, Jacob S et al (2011) Laparoscopic repair of pelvic organ prolapse by lateral suspension with mesh: a continuous series of 218 patients. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 39:127–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GYOBFE.2010.12.007

Mereu L, Tateo S, D’Alterio MN et al (2020) Laparoscopic lateral suspension with mesh for apical and anterior pelvic organ prolapse: a prospective double center study. Eur J Obstetr Gynecol Reproduct Biol 244:16–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.10.026

Lizee D, Campagna G, Morciano A et al (2017) Laparoscopic sacral colpopexy: how to place the posterior mesh into rectovaginal space? Neurourol Urodyn 36:1529–1534. https://doi.org/10.1002/NAU.23106

Mereu L, Dalpra F, Terreno E et al (2018) Mini-laparoscopic repair of apical pelvic organ prolapse (POP) by lateral suspension with mesh. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 10:139–145

Giannini A, Caretto M, Russo E et al (2019) Advances in surgical strategies for prolapse. Climacteric 22(1):60–64

Isenlik BS, Aksoy O, Erol O, Mulayim B (2023) Comparison of laparoscopic lateral suspension and laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with concurrent total laparoscopic hysterectomy for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Int Urogynecol J 34:231–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00192-022-05267-6/TABLES/4

Malanowska-Jarema E, Starczewski A, Melnyk M et al (2024) A Randomized clinical trial comparing dubuisson laparoscopic lateral suspension with laparoscopic sacropexy for pelvic organ prolapse: short-term results. J Clin Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM13051348

Acknowledgements

The Delphi project was supported by PFM Medical, the manufacturer of the T-shaped mesh used to perform lateral suspension, and SunMedical which coordinates the distribution of medical/surgical devices. We also must also mention OncoMedical, MPÖ PFM, Medical Cañada, and Medstron Medical for their support and for their collaboration in the project.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università di Pisa within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The Delphi project was supported by an unrestricted educational grant provided by PFM Medical, and Sun Medical, to Prof. Tommaso Simoncini—University of Pisa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Tommaso Simoncini has received consulting fees from Abbott, Astellas, Gedeon Richter, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Sojournix, Estetra, Mithra, Actavis, Medtronic, Shionogi, and Applied Medical and has received speakers’ honoraria from Shionogi, Gedeon Richter, Intuitive Surgical, Applied Medical, and Theramex. Ratiba Ritter has received consulting contract with PFM ag and TCB, Tina Cadenbach-Blome has received fees from A.M.I, Gedeon Richter, Gynesonics, Pfm medical ag, Rudolph medical, Theramex. Andrea Panattoni, Nicola Caiazzo, Maribel Calero García, Marta Caretto, Fu Chun, Eric Francescangeli, Giorgia Gaia, Andrea Giannini, Lucas Hegenscheid, Stefano Luisi, Paolo Mannella, Liliana Mereu, Maria Magdalena Montt-Guevara, Isabel Ñiguez, Maria Luisa Sanchez Ferrer, Ayman Tammaa, Eleonora Russo, Bernhard Uhl, Bea Wiedemann, Maciej Wilczak, Friedrich Pauli, and Jean Dubuisson have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (MP4 173359 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Simoncini, T., Panattoni, A., Cadenbach-Blome, T. et al. Role of lateral suspension for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse: a Delphi survey of expert panel. Surg Endosc (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-024-10917-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-024-10917-5