Abstract

Background

Various technical modifications of Nissen fundoplication (NF) that aim to improve patients’ outcomes have been discussed. This study aims to evaluate the effect of division of the short gastric vessels (SGV) and the addition of a standardized fundophrenicopexia on the postoperative outcome after NF.

Methods

283 consecutive patients with GERD treated with NF were divided into four groups following consecutive time periods: with division of the SGV and without fundophrenicopexia (group A), with division of the SGV and with fundophrenicopexia (group B), without division of the SGV and with fundophrenicopexia (group C) and without division of the SGV and without fundophrenicopexia (group D). Postoperative contrast swallow, dysphagia scoring, GEDR-HRQL and proton pump inhibitor intake were evaluated. A comparative analysis of patients with division of the SGV and those without (161 A + B vs. 122 C + D), and patients with fundophrenicopexia and those without (78 A vs. 83 B and 49 C vs. 73 D) was performed.

Results

Fundophrenicopexia reduced postoperative dysphagia rates (0 group C vs. 5 group D, p = 0.021) in patients where the SGV were preserved and reoperation rates (1 group B vs. 7 group A, p = 0.017) in patients where the SGV were divided. There was no significant difference in the postoperative rates of heartburn relief, dysphagia, gas bloating syndrome, interventions, re-fundoplication and the GERD-HRQL score between groups A + B and C + D, respectively.

Conclusion

Standardized additional fundophrenicopexia in patients undergoing Nissen fundoplication significantly reduces postoperative dysphagia in patients without division of the SGV and reoperation rates in patients with division of the SGV. Division of the SGV has no influence on the postoperative outcome of NF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) represents a public health issue with an increasing prevalence and high economic burden. [1,2,3,4] Patients have choose between medical and surgical therapy in an effort to improve their quality of life and prevent possible complications of long-term acid exposure as well as anti-acid treatment. [5] However, less than 1% of GERD patients ultimately opt for surgical GERD treatment. [2, 3, 6] Although the reason behind the decrease in anti-reflux operations noted over the last decades seems multifactorial, one possible explanation is the fear of short term adverse effects such as re-herniation and need for reoperation as well as long-term side effects like dysphagia and gas-bloat syndrome. [7,8,9,10]

The Nissen fundoplication (NF) underwent countless alterations in an attempt to reduce side effects, increase effectiveness and subsequently minimize the therapy gap between medical and surgical GERD treatment. [11,12,13] The original surgical technique consisted of the division of the phrenoesophageal ligament, mobilization of the esophagus, without division of the short gastric vessels (SGV) and wrapping of the anterior and posterior wall of the stomach 360° around the lower 6 cm of the esophagus using 4 or 5 interrupted sutures. [11] As dysphagia rates were high following such a procedure, partial 270° Toupet fundoplication and 120° Dor fundoplication were developed in Europe. [11, 13] Furthermore, DeMeester and Johnson modified the procedure to a loose “floppy Nissen” by dividing the SGV and proving that a maximal wrap of 2 cm was enough to provide reflux control but prevent dysphagia and gas bloating. [14, 15]

Nevertheless, the division of the SGV remains controversial and surgeon-dependent. [16,17,18] Although it has been claimed that dividing the SGV may minimize the risk of dysphagia [19], different studies failed to demonstrate both short and long-term benefits for patients that underwent this maneuver. [17, 18, 20,21,22] Moreover, some trials have reported a higher incidence of abdominal bloating and recurrent hiatal hernia as well as increased operating time including division of the SGV. [23,24,25] Furthermore, added posterior gastropexy aimed to reduce the re-herniation rate and lengthen the intraabdominal esophagus. Without worsening the dysphagia rates, posterior gastropexy has shown to have a positive impact on the postoperative outcome of NF. [26,27,28] Encouraged by these results we integrated suturing the fundoplication wrap with the right crus (fundophrenicopexia) with two non-resorbable sutures.

The aim of this study was to analyze the differences in postoperative dysphagia rates, reflux control, re-fundoplication rate as well as the degree of overall satisfaction in GERD patients who underwent laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication (NF) with and without division of the short gastric vessels and/or fundophrenicopexia in a high volume specialized reflux center.

Methods

Patient selection

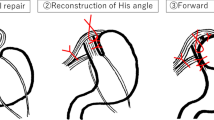

All consecutive patients that underwent NF between the years 2014 and 2019 were included. During this time period the procedure was consequently modified four times (see patients inclusion chart Fig. 1). From 01/2014 until 02/2015 all NF included full mobilization of the fundus with division of the upper half of the SGV. From 02/2015 until 08/2016 all NF included division of the SGV as well as fundophrenicopexia, with two non-absorbable sutures between the fundoplication wrap and right crus. From 08/2016 until 09/2017 we ceased fully mobilizing the fundus by dividing the SGV, while fundophrenicopexia was still performed. Finally from 09/2017 until 2019 no division of the SGV and no fundophrenicopexia was performed (see illustration of the four fundoplication modifications Fig. 1).

Preoperative assessment

All patients received a standardized interview, clinical examination, an upper GI endoscopy, a video esophagogram and esophageal functioning testing consistent of a manometry and a 24-h-impedance-pH-metry. GERD was diagnosed by positive pH results or increased total reflux episodes with positive symptom correlation on esophageal functioning tests, presence of esophagitis on endoscopy or typical GERD symptoms sensitive to PPI medication. Hiatal hernia was diagnosed with high precision using both upper GI endoscopy and high-resolution manometry.

Surgery

All procedures were performed by one of the senior surgeons who were part of the specialized upper GI surgical unit. (SFS, RA). The surgical approach was laparoscopic in all cases. All procedures were standardized regarding the surgeon’s and patient’s positions (anti-Trendelenburg), trocar sites and used instruments. These procedures were accomplished by hiatal dissection and crural closure with 1–5 stitches using non-absorbable sutures. All cases were performed without the use of an esophageal bougie.

Nissen fundoplication

LNF was performed in a highly standardized technique as described recently. [29] In brief: both crura of the diaphragm were dissected using the ultrasonic dissector to expose the distal esophagus. Special care was taken to achieve an adequate “intraabdominalisation” of the lower esophagus of at least 3 cm in length. An extra-short wrap, measuring 1.5 cm in a maximum with the naked eye was created using 2 close stiches with non-absorbable sutures. The first stich included the anterior esophageal wall. The vagal nerve was always identified and included in the wrap. After the operation was completed, a blunt laparoscopic instrument was placed between the posterior esophageal wall and the wrap to determine the looseness of the fundoplication.

Postoperative care

All patients undergoing LNF received a restricted semiliquid food diet for the first 10 days, slowly progressing to solid food to avoid dysphagia during the development of mucosal edema. On the first postoperative day a contrast swallow with diatrizoate was performed in all patients. After at least one overnight stay, patients were discharged from the hospital once they displayed an unremarkable postoperative contrast swallow.

Postoperative assessment

For analysis, all patients were divided into four groups following the consecutive time periods (see patients chart): NF with division of the SGV and without fundophrenicopexia (group A), NF with division of the SGV and with fundophrenicopexia (group B), NF without division of the SGV, but with fundophrenicopexia (group C) and NF without division of the SGV and without fundophrenicopexia (group D). These groups were included in a comparative analyses (A + B vs. C + D). Furthermore, we performed a comparative analysis of patients that underwent NF with fundophrenicopexia and those without, within the two main groups (A vs. B and C vs. D).

The median follow-up time was 5 years (IQR, 1.8–10). Follow-up was performed by the same physician using a standardized interview assessing postoperative gastrointestinal symptoms, proton pump inhibitor intake (PPI), GERD-Health-related-Quality-of-Life (GERD-HRQL) and overall Alimentary Satisfaction (AS). The overall AS was assessed using a scale from 0 – 10 of Greene et al., where the score 0 indicated an intolerable alimentary function while a score of 10 indicated complete satisfaction. [30] The frequency and severity of postoperative dysphagia was assessed using the classification of Saeed et al., where the ability to swallow can be scored from 0 to V, where 0 is inability to swallow and V is normal swallowing (Table 4.). [31]

Adverse events such as complications, hospital readmission, emergency operation or elective reoperation were documented. Patients with recurrent symptoms received upper GI endoscopy as well as esophageal functioning tests.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® statistics 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Data were described using median (interquartile range (IQR)) or mean (range). Statistical analysis appropriate for non-parametric data were used. Categorical variables were assessed using the Fisher exact test and continuous data using the Wilcoxon Rank test as appropriate. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05.

Results

A total of two hundred and eighty three (n = 283) consecutive patients that underwent laparoscopic NF were included for comparative analyses. One hundred and sixty one (57% groups A + B) patients underwent division of the short gastric vessels whereas in one hundred and twenty-one (43% groups C + D) patients no division of the short gastric vessels had been performed. There was no significant difference in age, sex, body mass index (BMI), preoperative total number of reflux episodes, hiatal hernia size and presence of Barrett’s esophagus between the groups. Each group was then further divided into a subgroup depending if a fundophrenicopexia was performed. Demographics and preoperative findings are shown in Table 1.

Operative parameters

The surgical approach was laparoscopic in all patients. The median operation time (OR) time was 55 min (IQR, 40 – 80 min). There was a significant difference in the operation time when comparing the two groups (55 min groups A + B vs. 40 min groups C + D, p = 0.002). No intraoperative complications were seen. Postoperative swallow X-ray showed regular postoperative results in all patients.

Symptom relief

The median follow-up time was 5 years (IQR, 1.8–10). Heartburn was fully eliminated in two hundred and twenty-nine patients (n = 229/277, 83%), while regurgitations were improved in one hundred and sixty-nine patients (n = 169/183, 92%) and fully eliminated in one hundred and forty-three (n = 143/183, 78%) of the patients. When analyzing the pre- and postoperative symptoms we found a statistically significant difference between all three symptoms. A comparison of the two most reported symptoms before and after NF is shown in Table 2.

Side effects

Forty (14%) patients reported they were unable to belch/vomit and thirty-five (12%) patients complained about increased daily gas bloating. There was no difference in the postoperative inability to belch/vomit (17 groups A + B vs. 23 groups C + D, p = 0.071) or in daily gas bloating (19 groups A + B vs. 16 groups C + D, p = 0.740) between the groups. Summary of postoperative side effects are presented in Table 3.

Dysphagia

Persistent dysphagia, defined as 0, I or II in the classification of Saeed et al., was reported in eleven (n = 11, 4%) patients at the time of follow-up. [31] The frequency and degree of postoperative dysphagia is shown in Table 4. When comparing the patients that had no division of the SGV we found a significant difference in the postoperative persistent dysphagia rate between group C (0%) and D (7%) in favor of group C (p = 0.021). There was no difference in the occurrence of persistent dysphagia when comparing patients with and without the division of the SGV (6 groups A + B vs. 5 groups C + D, p = 0.873). Furthermore, no difference in the persistent dysphagia rate was observed between group A (4%) and group B (4%) when comparing patients with division of the SGV (p = 0.938).

Out of 11 patients with persistent dysphagia, we observed two patients with slipping of the fundoplication wrap, only one of which underwent a surgical revision. One patient developed a rupture of the wrap 2 years after the primary operation with reflux reoccurrence and underwent a surgical revision of the wrap, after which he developed dysphagia and underwent a third operation 6 months after the revision, where a couple adhesions were divided. Two out of three patients with persistent dysphagia showing no morphological abnormalities in postoperative investigations underwent one or more endoscopic balloon dilatations, one of which underwent a conversion to a Toupet fundoplication two years later. Five patients with persistent dysphagia did not undergo further diagnostic evaluation.

No correlation was found between preoperative ineffective esophageal motility (IEM) and postoperative dysphagia (p = 0.645), as only 1 out of 11 patients with persistent dysphagia was diagnosed with IEM prior to the operation.

Interventions and revision operation

Endoscopic dilatation was performed in six patients (2%) with persistent dysphagia, with four of them having a successful outcome, leaving two patients with persistent dysphagia at the time of follow-up. Sixteen (6%) patients required re-fundoplication operation. Six patients underwent revision operation due to dysphagia, four patients developed re-herniation of the fundus/wrap, four patients developed rupture of the fundoplication wrap and reoccurrence of reflux symptoms, one patient developed slipping of the fundoplication wrap and lastly, one patient developed gastric carcinoma and needed gastric resection. Nine patients (n = 9/16, 56%) underwent revision operation within one year after the primary operation, five patients (n = 5/16, 31%) underwent revision operation one to three years after the primary operation and two patients (n = 2/16, 13%) underwent revision operation three to five years after the primary operation.

There was no difference in the postoperative rate of endoscopic dilatation between the two groups (3 groups A + B vs. 3 groups C + D, p = 0.567), or between either of the subgroups. We found no difference in the rates of reoperation between the two groups (8 groups A + B vs. 8 groups C + D, p = 0.236). Even though there was a clear trend towards a reduced revision rate in patients without division of the SGV and fundophrenicopexia when compared to those without division of the SGV and without fundophrenicopexia (1 group C vs. 7 group D, p = 0.075), it missed statistical significance. However, in the group of patients that had undergone division of the SGV and fundophrenicopexia a significant reduced reoperation rate when compared to those with division and without fundophrenicopexia was found (1 group B vs. 7 group A, p = 0.017).

Quality of life

Prior to the operation 98 patients had completed the GERD-HRQL score. The preoperative median total GERD-HRQL score was 19.5 (IQR 13 – 25). Laparoscopic NF led to a significant reduction of the GERD-HRQL total score (19.5 vs. 2, p = 0.00). When comparing patients with and without division of the SGV we see no difference in the postoperative GERD-HRQL score (2 groups A + B vs. 2 groups C + D, p = 0.802). Moreover, the median AS was rated 9, also with no difference between the groups (9 groups A + B vs. 10 groups C + D, p = 0.074). Two hundred and fifty-six patients (n = 256, 90%) reported being satisfied with their outcome after NF, with minimal difference between the groups (141 groups A + B vs. 115 groups C + D, p = 0.049). Two hundred and thirty-nine (n = 239, 84%) claimed they would undergo the same operation again, with no difference between the groups (130 groups A + B vs. 109 groups C + D, p = 0.097). This proves a substantial increase in quality of life in our patients. One hundred and ninety-eight (n = 198/251, 79%) patients reported to be completely free of PPIs postoperatively, while twenty-three (n = 23/251, 9%) patients needed regular PPI use. No difference was observed in the postoperative rate of PPI use between the two groups (31 groups A + B vs. 22 groups C + D, p = 0.784).

Discussion

The laparoscopic NF has been the gold standard in anti-reflux surgery to date, achieving up to 20 years of effective reflux control and significant improvement of quality of life. [5, 21, 32,33,34] Nonetheless, the NF has also been associated with certain adverse effects, such as persistent dysphagia and gas-bloat syndrome. [7,8,9,10, 35] Furthermore, although minimal, a risk of fundoplication failure, defined as re-herniation, slipping of the wrap or reoccurrence of symptoms requiring reoperation also exists. [8, 36,37,38] Throughout history surgeons have been trying to optimize the procedure, modifying certain segments to reduce the complication rate. [11,12,13] Still no consensus exists whether the SGV should be ligated or not or whether the fundoplication wrap or/and remaining stomach should be fixated to the crus or not. [21, 26,27,28, 39, 40] Thus, it ultimately depends on the surgeon how the NF is performed precisely. Creating a 360° tension-free wrap, no longer then 1,5 cm length, with two non-absorbable sutures, including the esophagus in the first one remained the basis of our NF from beginning to date. Similarly though, the procedure underwent modifications throughout the years: (1) full mobilization of the fundus with division of the short gastric vessels, but without fundophrenicopexia, (2) full mobilization of the fundus with division of the short gastric vessels and fundophrenicopexia, (3) mobilization of the fundus without diving the short gastric vessels, but with fundophrenicopexia and finally (4) mobilization of the fundus without diving the short gastric and fundophrenicopexia. Therefore, in this study we aim to compare the postoperative outcome of patients that underwent these four modifications of the NF in our high output surgical reflux center.

In our study we observed a total of eleven patients (4%) with postoperative persistent dysphagia at the time of follow-up. These results coincide with previous literature where dysphagia after NF ranges from 2 to 11%. [29, 34, 41] The hypothesis that division of the SGV is needed to achieve a tension-free fundoplication wrap and thus minimize the risk of postoperative dysphagia led to many surgeons integrating this step in the NF. [14, 15, 19] However, multiple randomized prospective studies have shown no impact of this intraoperative modification in the reduction of the above mentioned adverse effect. [16,17,18, 22, 39, 40] Moreover, a higher incidence of postoperative bloating, re-herniation and longer operating time has been described in patients that underwent the additional modification of the NF. [20, 23,24,25] Our results are similar to previous literature showing no difference in postoperative dysphagia rates in patients with and those without division of the SGV (6 groups A + B vs. 5 groups B + C, p = 0.873). Similarly, we also found longer operating time in patients where the SGV were divided (55 min groups A + B vs. 40 min groups C + D, p = 0.002). However, in contrast to some studies we found no significant difference in postoperative gas bloating (19 groups A + B vs. 16 groups C + D, p = 0.740) or reoperation between the two groups (8 groups A + B vs. 8 groups C + D, p = 0.567). Additionally, no difference was seen in the postoperative inability to belch/vomit (17 groups A + B vs. 23 groups C + D, p = 0.071). These results show us that additional division of the SGV has no benefit on the postoperative side-effect rate after NF.

Intrathoracic wrap migration/herniation, wrap disruption and telescoping/slipping have been shown as the most common causes of fundoplication failure. [42] As the gastroesophageal junction is thoroughly dissected and the esophagus maximally intraabdominalized, the positive intraabdominal pressure can cause the free wrap to migrate to the negative pressure, into the thorax. [37] In order to minimize this risk we added extra one or two sutures between the fundoplication wrap and the right crus – fundophrenicopexia in our NF. In our series we had sixteen patients (6%) that needed reoperation and six (2%) needing balloon dilatation. These results are also similar to previous literature showing revision rates from 3 – 6%, or in long-term follow-up from 5 – 15%. [43, 44] Interestingly, when looking closer at our group with division of the SGV and comparing the two subgroups with patients undergoing additional fundophrenicopexia and those without, we found a significant difference in the revision rate between the patients (1 group B vs. 7 group A, p = 0.017). The most common cause for reoperation were fundoplication wrap disorders: re-herniation, slipping and disruption (n = 4/7, 60%). This finding shows us that additional fundophrenicopexia in patients where full fundus mobilization is preformed anchors the fundoplication in its intraabdominal place reducing the risk of migration or slipping. Another interesting finding was the difference in persistent dysphagia rates in patients where no division of the SGV was performed (0 group C vs. 5 group D, p = 0.021). A possible explanation for this outcome could be that anchoring the wrap to the right crus relives the pressure from the spleen to the gastric fundus and prevents the kinking of the esophagus, when the SGV are not dissected, reducing further dysphagia. Nonetheless further prospective studies are needed to confirm the benefit of additional fundophrenicopexia in the NF.

We also found no correlation between preoperative IEM and postoperative dysphagia (p = 0.645). These findings confirm multiple previous studies showing no influence of the type of fundoplication on the outcome in patients with IEM [45,46,47,48,49,50], although still controversial.

In this study all the procedures were performed without the use of a bougie. Even though the results of a small prospective randomized study had shown lower dysphagia rates when applying a bougie during laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, certain limitations of this study such as additional concurrent laparoscopic procedures that 34 patients underwent (unknown in which group), as well as the validity of the scoring system used to assess the dysphagia should be taken into consideration. [51] Furthermore, various studies reported no benefit of using a bougie in postoperative dysphagia rates as well as a higher risk of esophageal perforation potentially opposing the benefit. [52,53,54,55,56]

When observing the quality of life in our patients, we found that it significantly increases after NF (GERD-HRQL total score 19.5 vs. 2, p = 0.00). Moreover, the median AS was rated 9, two hundred and fifty-six patients ( 90%) reported being satisfied with their outcome after NF and two hundred and thirty-nine (84%) claimed they would undergo the same operation again. Finally when comparing the three most common GI symptoms – heartburn, regurgitation and respiratory symptoms, before and after FN we found a significant reduction of all three symptoms after the operation (with and without the division of the SGV (Table 2). These results further show that NF makes a substantial difference in symptom relief and GI quality of life in GERD patients.

A few limitations of our study, like its retrospective nature need to be taken into consideration. The various modifications were implemented over a time period and patients were not prospectively randomized, with the hopes of improving the outcome while reducing the side-effect rate. The patients in this study were selected consecutively and were prone to selection bias. Further prospective, controlled studies are needed to confirm the proposed benefits of such a modification in the NF with a higher level of evidence. Also, we relied purely on subjective postoperative patient evaluation of outcomes, as the majority of the patients were asymptomatic and invasive objective (EFTs) testing was difficult in the large cohort.

Conclusion

At a median follow-up of five years the NF is shown to be a safe and effective operation in reflux control. We found additional division of the SGV has no benefit on the postoperative outcome of the NF. On the contrary additional suturing of the fundoplication wrap to the right crus reduces the risk of re-fundoplication when the SGV are ligated and reduces the risk of postoperative dysphagia when the SGV are not ligated. These results have established Nissen fundoplication performed without division of the SGV and with a standard fundophrenicopexia as the standard modification at our center.

References

Yamasaki T, Hemond C, Eisa M, Ganocy S, Fass R (2018) The changing epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: are patients getting younger? J Neurogastroenterol Motil 24(4):559–569

Reynolds JL, Zehetner J, Nieh A, Bildzukewicz N, Sandhu K, Katkhouda N, Lipham JC (2016) Charges, outcomes, and complications: a comparison of magnetic sphincter augmentation versus laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for the treatment of GERD. Surg Endosc 30(8):3225–3230

Warren HF, Reynolds JL, Lipham JC, Zehetner J, Bildzukewicz NA, Taiganides PA, Mickley J, Aye RW, Farivar AS, Louie BE (2016) Multi-institutional outcomes using magnetic sphincter augmentation versus Nissen fundoplication for chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc 30(8):3289–3296

El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J (2014) Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut 63(6):871–880

Alemanno G, Bergamini C, Prosperi P, Bruscino A, Leahu A, Somigli R, Martellucci J, Valeri A (2017) A long-term evaluation of the quality of life after laparoscopic Nissen-Rossetti anti-reflux surgery. J Minim Access Surg 13(3):208–214

Reynolds JL, Zehetner J, Wu P, Shah S, Bildzukewicz N, Lipham JC (2015) Laparoscopic magnetic sphincter augmentation vs laparoscopic nissen fundoplication: a matched-pair analysis of 100 patients. J Am Coll Surg 221(1):123–128

Wang YR, Dempsey DT, Richter JE (2011) Trends and perioperative outcomes of inpatient antireflux surgery in the United States, 1993–2006. Dis Esophagus 24(4):215–223

Richter JE (2013) Gastroesophageal reflux disease treatment: side effects and complications of fundoplication. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 11(5):465–471

Ganz RA, Peters JH, Horgan S (2013) Esophageal sphincter device for gastroesophageal reflux disease. N Engl J Med 368(21):2039–2040

Khan F, Maradey-Romero C, Ganocy S, Frazier R, Fass R (2016) Utilisation of surgical fundoplication for patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in the USA has declined rapidly between 2009 and 2013. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 43(11):1124–1131

Stylopoulos N, Rattner DW (2005) The history of hiatal hernia surgery: from Bowditch to laparoscopy. Ann Surg 241(1):185–193

Wang B, Zhang W, Liu S, Du Z, Shan C, Qiu M (2015) A Chinese randomized prospective trial of floppy Nissen and Toupet fundoplication for gastroesophageal disease. Int J Surg 23(Pt A):35–40

Moore M, Afaneh C, Benhuri D, Antonacci C, Abelson J, Zarnegar R (2016) Gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review of surgical decision making. World J Gastrointest Surg 8(1):77–83

DeMeester TR, Johnson LF (1975) Evaluation of the Nissen antireflux procedure by esophageal manometry and twenty-four hour pH monitoring. Am J Surg 129(1):94–100

DeMeester TR, Bonavina L, Albertucci M (1986) Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Evaluation of primary repair in 100 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 204(1):9–20

O’Boyle CJWD, Jamieson GG, Myers JC, Game PA, Devitt PG (2002) Division of short gastric vessels at laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: a prospective double-blind randomized trial with 5-year follow-up. Ann Surg 235(2):165–170

Kosek V, Wykypiel H, Weiss H, Holler E, Wetscher G, Margreiter R, Klaus A (2009) Division of the short gastric vessels during laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: clinical and functional outcome during long-term follow-up in a prospectively randomized trial. Surg Endosc 23(10):2208–2213

Ielpo BMP, Vazquez R, Corripio R, San Roman J, Acedo F, La Puente F, Torres A, Gravante G, Fernandez-Nespral V (2011) Long-term results of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with or without short gastric vessels division. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 21:267–270

Leggett PL, Bissell CD, Churchman-Winn R, Ahn C (2000) A comparison of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication and Rossetti’s modification in 239 patients. Surg Endosc 14(5):473–477

Engstrom C, Jamieson GG, Devitt PG, Watson DI (2011) Meta-analysis of two randomized controlled trials to identify long-term symptoms after division of the short gastric vessels during Nissen fundoplication. Br J Surg 98(8):1063–1067

Kinsey-Trotman SP, Devitt PG, Bright T, Thompson SK, Jamieson GG, Watson DI (2018) Randomized trial of division versus nondivision of short gastric vessels during nissen fundoplication: 20-year outcomes. Ann Surg 268(2):228–232

Teixeira AC, Herbella FA, Bonadiman A, Farah JF, Del Grande JC (2015) Predictive factors for short gastric vessels division during laparoscopic total fundoplication. Rev Col Bras Cir 42(3):154–158

Pessaux P, Arnaud JP, Delattre JF, Meyer C, Baulieux J, Mosnier H (2005) Laparoscopic antireflux surgery: five-year results and beyond in 1340 patients. Arch Surg 140(10):946–951

Chrysos E, Tzortzinis A, Tsiaoussis J, Athanasakis H, Vasssilakis J, Xynos E (2001) Prospective randomized trial comparing Nissen to Nissen-Rossetti technique for laparoscopic fundoplication. Am J Surg 182(3):215–221

Luostarinen ME, Isolauri JO (1999) Randomized trial to study the effect of fundic mobilization on long-term results of Nissen fundoplication. Br J Surg 86(5):614–618

Nissen R (1961) Gastropexy and “fundoplication” in surgical treatment of hiatal hernia. Am J Dig Dis 6:954–961

Tsimogiannis KE, Pappas-Gogos GK, Benetatos N, Tsironis D, Farantos C, Tsimoyiannis EC (2010) Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication combined with posterior gastropexy in surgical treatment of GERD. Surg Endosc 24(6):1303–1309

Davis CS, Fisichella PM (2011) Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication combined with posterior gastropexy in the surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Surg Endosc 25(6):2055

Nikolic M, Schwameis K, Semmler G, Asari R, Semmler L, Steindl A, Mosleh BO, Schoppmann SF (2018) Persistent dysphagia is a rare problem after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Surg Endosc 33(4):1196–1205

Greene CL, DeMeester SR, Worrell SG, Oh DS, Hagen JA, DeMeester TR (2014) Alimentary satisfaction, gastrointestinal symptoms, and quality of life 10 or more years after esophagectomy with gastric pull-up. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 147(3):909–914

Saeed ZA, Winchester CB, Ferro PS, Michaletz PA, Schwartz JT, Graham DY (1995) Prospective randomized comparison of polyvinyl bougies and through-the-scope balloons for dilation of peptic strictures of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 41(3):189–195

Robinson B, Dunst CM, Cassera MA, Reavis KM, Sharata A, Swanstrom LL (2015) 20 years later: laparoscopic fundoplication durability. Surg Endosc 29(9):2520–2524

Prassas D, Krieg A, Rolfs TM, Schumacher FJ (2017) Long-term outcome of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in a regional hospital setting. Int J Surg 46:75–78

Schietroma M, Piccione F, Clementi M, Cecilia EM, Sista F, Pessia B, Carlei F, Guadagni S, Amicucci G (2017) Short- and Long-Term, 11–22 Years, Results after Laparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication in Obese versus Nonobese Patients. J Obes 2017:7589408

Schwameis K, Zehetner J, Rona K, Crookes P, Bildzukewicz N, Oh DS, Ro G, Ross K, Sandhu K, Katkhouda N et al (2017) Post-nissen dysphagia and bloating syndrome: outcomes after conversion to toupet fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 21(3):441–445

Smith CD, McClusky DA, Rajad MA, Lederman AB, Hunter JG (2005) When fundoplication fails: redo? Ann Surg 241(6):861–869

Bardini R, Rampado S, Salvador R, Zanatta L, Angriman I, Degasperi S, Ganss A, Savarino E (2017) A modification of Nissen fundoplication improves patients’ outcome and may reduce procedure-related failure rate. Int J Surg 38:83–89

Price MR, Janik JS, Wayne ER, Janik JE, Martinez LA, Burrington JD (1997) Modified Nissen fundoplication for reduction of fundoplication failure. J Pediatr Surg 32(2):324–326

Yang H, Watson DI, Lally CJ, Devitt PG, Game PA, Jamieson GG (2008) Randomized trial of division versus nondivision of the short gastric vessels during laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: 10-year outcomes. Ann Surg 247(1):38–42

Markar SRKA, Wagner OJ, Jackson D, Hewes JC, Vyas S, Hashemi M (2011) Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with or without division of the short gastric vessels. Br J Surg 98(8):1056–1062

Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, Attwood S, Ell C, Fiocca R, Eklund S, Langstrom G, Lind T, Lundell L, Collaborators LT (2011) Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 305(19):1969–1977

Furnee EJ, Draaisma WA, Broeders IA, Gooszen HG (2009) Surgical reintervention after failed antireflux surgery: a systematic review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg 13(8):1539–1549

Celasin H, Genc V, Celik SU (2017) Turkcapar AG Laparoscopic revision surgery for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 96(1):5779

Schietroma M, De Vita F, Carlei F, Leardi S, Pessia B, Sista F, Amicucci G (2013) Laparoscopic floppy Nissen fundoplication: 11-year follow-up. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 23(3):281–285

Booth MI, Stratford J, Jones L, Dehn TC (2008) Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic total (Nissen) versus posterior partial (Toupet) fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease based on preoperative oesophageal manometry. Br J Surg 95(1):57–63

Strate UEA, Fibbe C, Layer P, Zornig C (2008) Laparoscopic fundoplication: Nissen versus Toupet two-year outcome of a prospective randomized study of 200 patients regarding preoperative esophageal motility. Surg Endosc 22(1):21–30

Jobe BAWJ, Hansen PD (1997) Swanstrom LL Evaluation of laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication as a primary repair for all patients with medically resistant gastroesophageal reflux. Surg Endosc 11(11):1080–1083

Patti MGRT, Galvani C, Gorodner MV, Fisichella PM, Way LW (2004) Total fundoplication is superior to partial fundoplication even when esophageal peristalsis is weak. J Am Coll Surg 198(6):863–869

Nikolic M, Schwameis K, Kristo I, Paireder M, Matic A, Semmler G, Semmler L, Schoppmann SF (2020) Ineffective esophageal motility in patients with GERD is no contraindication for nissen fundoplication. World J Surg 44(1):186–193

Laliberte AS, Louie BE, Wilshire CL, Farivar AS, Bograd AJ, Aye RW (2020) Ineffective esophageal motility is not a contraindication to total fundoplication. Surg Endosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07883-z

Patterson EJ, Herron DM, Hansen PD, Ramzi N, Standage BA, Swanstrom LL (2000) Effect of an esophageal bougie on the incidence of dysphagia following nissen fundoplication: a prospective, blinded, randomized clinical trial. Arch Surg 135(9):1055–1061

Somasekar KM-SG, Al-Madfai H, Barton K, Hassn A (2010) Is a bougie required for the performance of the fundal wrap during laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication? Surg Endosc 24(2):390–394

Zacharoulis D, O’Boyle CJ, Sedman PC, Brough WA, Royston CM (2006) Laparoscopic fundoplication: a 10-year learning curve. Surg Endosc 20(11):1662–1670

Lowham AS, Filipi CJ, Hinder RA, Swanstrom LL, Stalter K, dePaula A, Hunter JG, Buglewicz TG, Haake K (1996) Mechanisms and avoidance of esophageal perforation by anesthesia personnel during laparoscopic foregut surgery. Surg Endosc 10(10):979–982

Ng A, Yong D, Hazebroek E, Berry H, Radajewski R, Leibman S, Smith GS (2009) Omission of the calibration bougie in laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Surg Endosc 23(11):2505–2508

Walsh JDLJ, Boyd WC, Lambert PJ, Havlik PJ (2003) Patient outcomes and dysphagia after laparoscopic antireflux surgery performed without use of intraoperative esophageal dilators. Am Surg 69(3):219–223

Funding

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna. No financial support or other assistance received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors listed above contributed substantially to the conception or design of the work and the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; and all authors contributed to the drafting of the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content and the final approval of the version to be published; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

No financial support was received for this study. Nikolic M., Matic A.., Kristo I., Paireder M., Asari R., Osmokrovic B., Semmler G., and Schoppmann S. have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This study (2293/2017) was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nikolic, M., Matic, A., Kristo, I. et al. Additional fundophrenicopexia, after Nissen fundoplication, reduces postoperative dysphagia and re-operation rate in the long-term follow up. Surg Endosc 36, 3019–3027 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08598-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08598-5