Abstract

Stochasticity in food availability influences vital rates such as survival and fertility. Life-history theory predicts that in long-lived organisms, survival should be buffered against environmental stochasticity showing little temporal variability. Furthermore, to optimize survival prospects, many animal species perform migrations to wintering areas where food availability is larger. Species with large latitudinal distribution ranges may show populations that migrate and others that are resident, and they may co-occur in winter. One example of these species is the predatory raptor buzzard Buteo buteo. Here, we test whether temporal variability in the density of five small mammal species of prey inhabiting different habitats (shrubland and forests) influences local annual survival of buzzards in a wintering area depending on their age and residency status (residents versus wintering individuals). We found that prey density explained a considerable amount of annual changes in local survival, which was higher for older and resident birds. This difference in local survival likely corresponded to philopatry to the wintering area, which was larger for residents and increased when prey density was larger. The total density of prey inhabiting open shrublands was the variable explaining more variance in temporal variability of local survival, even though the study area is mostly occupied by woodlands. Temporal population dynamics of the different small mammals inhabiting shrublands were not synchronous, which suggests that buzzards preyed opportunistically on the most abundant prey each winter. Generalist predation may buffer the impact of resource unpredictability for pulsed and asynchronous prey dynamics, typical of small mammals in winter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The importance of food availability for most vital rates, such as recruitment, survival and fertility, depends on life-history strategies. For short-lived species, stochastic variability in food availability and predators largely influence their population dynamics (bottom-up and top-down regulation, respectively) (Hanski et al. 1993; Frederiksen et al. 2006). For long-lived animals lacking predators, fluctuations in prey availability, in the absence of additive mortality, regulate their population dynamics by density-dependence (Saether and Bakke 2000; Millon et al. 2019). Life-history theory predicts that survival of long-lived organisms tends to be buffered against environmental stochasticity, whereas other traits such as recruitment, skip breeding and mainly fertility are more sensitive to this stochasticity (Lande et al. 2003; Karell et al. 2009). Raptors are among these species, being both top predators and long-lived organisms. In recent years, numerous raptor studies have estimated their survival rates and how they vary as a function of individual covariates (e.g., sex, age) for several species (see review in Newton et al. 2016). Survival, especially those of adult birds, tends to be constant over the years, and this pattern is altered mainly by anthropogenic impacts on survival (Sergio et al. 2011; Martínez-Abraín et al. 2012; Tavecchia et al. 2012; Badia‐Boher et al. 2019). Nevertheless, the ecological processes affecting raptor survival, and more particularly the density of prey, remain little known. This is particularly true because most raptors are territorial and sample sizes are often small, which represents a challenge to assess the ecological processes influencing temporal fluctuations in survival. Proxies of food availability, such as global climatic and vegetation cover indexes, have been also occasionally used to test their influence on survival (Grande et al. 2009; Mihoub et al. 2010). Furthermore, stochasticity in prey densities may occur over time (seasonality in prey fluctuations) and space (spatial heterogeneity in prey densities) and this may influence spatio-temporal variability in raptor survival (McClure et al. 2020). A paradigmatic example is cycles in small mammal densities and their influence on survival of predators in high-latitude ecosystems (Brommer et al. 2002; Karell et al. 2009; Millon et al. 2014). Spatio-temporal variability in survival may be particularly acute also for long-lived migrant birds moving in large geographical areas, and selecting a suitable wintering area may optimise survival probabilities and fitness prospects (Harris et al. 2005; Genovart et al. 2013; Klaassen et al. 2014; Sergio et al. 2014b). Yet, some species may have distinct populations with strategies being either resident or migrant and with consequences for population heterogeneity in individual survival and population dynamics (Sanz-Aguilar et al. 2012, 2015). Examples of these species are those with mainland and island populations, with large distribution ranges, and with opportunistic habits for exploiting anthropogenic food subsidies (such as wolves, kites, gulls, and storks). Here, we test whether temporal variability in the density of five small mammal potential prey species influences local annual survival of common buzzards Buteo buteo in a Mediterranean wintering area depending on their age and residency status (i.e., residents versus wintering birds). These small mammals have varying seasonal life cycles and inhabit different habitats (shrubland and forests) (Diaz et al. 2010; Torre et al. 2020). Since buzzards are opportunistic predators (Graham et al. 1995; Reif et al. 2004), we expect that local survival will be influenced by the density of the commonest prey species each year. We also expected higher dependency on small mammals in autumn–winter, owing that alternative prey such as reptiles and insects commonly consumed by buzzards during the breeding season in this area are unavailable. Small mammal densities in winter are higher in open habitats (Torre et al. 2018), thus we will also test the hypothesis that small mammals inhabiting forests should have a lower influence on local survival than those occupying open habitats, where buzzards in the study area are commonly hunting (Grajera and Carbonell 2017).

Methods

Study area

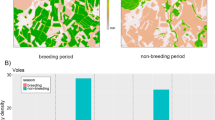

The study area is ca. 50 km2 and is located over a coastal mountain range (Barcelona, Catalonia, NE Spain, Fig. 1). Habitat is mainly composed of dense forests of pines (mainly Pinus pinea) and oak trees (mainly Quercus ilex), with patches of riverside forests associated with small streams, cereal, and set aside fields, orchard, and some urban areas (altitude: 79–380 m.a.s.l.). Forests and open habitats (shrublands and crops) occupy ca. 73 and 18% of the surface, respectively, with the remaining 9% covered by urban areas. In the study area, buzzards triple in density during winter due to the arrival of wintering individuals, compared to the density recorded during the breeding season (Grajera and Carbonell 2017).

Capture field protocols for buzzards and small mammals

From 2009 to 2019, we marked 111 wintering visitors (66 first winter and 45 older birds) and 36 residents (7 first winter–marked as chicks, see below, and 29 adults breeding in the area) buzzards. Birds were caught depending on the circumstances (mist nets, noose traps, Swedish hawk traps, and crossbow netting). Chicks born in the area were marked at the nests, which were previously located during the spring fieldwork season. We found sixteen breeding territories within the study area (and five additional territories that partially overlap their boundaries within this area), which shows that the density of breeding buzzards was high (ca. one territory each 3.1 km2). We assumed that we did not miss any breeding territory in this study area, owing that breeding buzzards are territorial and perform territorial flights over the nests, which are very conspicuous. Residents were marked mostly in their territories during breeding, and wintering birds were marked from late autumn to late winter (October–February). Resident birds were considered “marked” in the capture–recapture matrix when first resighted or recaptured during the wintering season to ensure that first-year local survival of all marked birds corresponded to the same amount of time. Birds were marked using a colour wing-tag in each wing, a metal ring in one leg, and a colour ring in the other leg with an individual alphanumeric code. To assess tag loss, we used different methods combined: the three types of marks (four marks in total), the plumage features (buzzards show high individual plumage variability), the moult pattern, and the high number of detailed observations of each individual mostly while perching on poles (> 90% from total observations) (mean = 33 observations, median = 11, range = 2–441). During the study, tag loss was anecdotal (only one individual confirmed) and not considered in our capture-recapture modelling. Resident birds were distinguished from wintering visitors partially by their plumage and the intensive monitoring of the breeding population in the study area (Grajera and Carbonell 2017). This monitoring included 27 breeding events monitored over the study by remote cameras with motion sensor for the study of the diet in a number of nests (average: 3.4 nests/year, range: 1–4) (unpublished data). Cameras were set for long periods (11 days ± 13 SD per nest, n = 279 camera-days) and allowed us to confirm the residency status of adults caught out of the breeding season. Resights of wing-tags from the distance allowed us the identification of breeding resident birds not monitored using nest-cameras in the study area. Furthermore, for chicks marked in the nest and adults trapped within their breeding territories, their origin was certain. Plumage was categorized in three categories: dark (84% of caught birds), intermediate (10%) and white (6%). We assumed that plumages of the two later categories corresponded to wintering birds coming from northern latitudes; all breeding birds marked and chicks marked in the nest and caught in the first winter during the study showed dark plumages. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out that some non-resident birds with dark plumages originated from northern latitudes or relatively close areas. In any case, we categorized the individuals as residents and wintering visitors, this last category including birds from both northern latitudes and closer areas. Age was assigned using EURING methodology and plumage characteristics following previous studies from southern Europe (Zuberogoitia et al. 2005) and due to the small sample size, only two groups were defined: birds in their first winter (including birds born in the study area and marked at the nest) and older birds. During each winter, resightings of marked birds were performed by car and walking transects over the study area, as well as using bait camera trapping and trapping for specific cases. We spent an average of 8 h each week Trapping allowed us to recapture some marked birds that were difficult to resight due to their tendency to hunt in woodlands. The effort of marking and resighting was kept relatively constant for the sampling winter periods over the years (mean = 4.8 days/week; SD = 1.7).

Small mammal relative densities and their annual variability were recorded using a standard grid-trapping long-term monitoring scheme (Torre et al. 2018). Sampling was performed each autumn (October–December) from 2009 to 2019, following the SEMICE monitoring scheme (Torre et al. 2018). Sampling plots were set in grids to include 36 traps (6 × 6 trapping scheme) spaced 15 m, alternating in position 18 Sherman traps (Sherman Co., USA) with 18 Longworth traps (Penlon Ltd., Oxford, UK). Traps were baited with food and insulated by including hydrophobic cotton for bedding. Traps were operated during three consecutive nights and revised each day during the early morning. Standardized sampling effort allowed establishing the relative abundance of common small mammal species in buzzard’s territories, by gathering the information recorded in eight nearby stations to the study area (Fig. 1). Stations were placed in two types of contrasted habitats: forests and shrublands-grasslands (Mediterranean maquis of Quercus coccifera and other fire-adapted resprouting species). These two contrasting habitats showed strong differences in suitability for small mammals regarding several abiotic and biotic factors (Torre et al. 2020). Population relative densities were obtained using TRIM software for the analysis of time series of counts with missing observations (Pannekoek and Van Strien 2005). Distance from the centre of the buzzard study area to small mammal sampling stations ranged between 5 and 24 km. Densities of small mammals showed spatial synchrony within years and between habitats (Diaz et al. 2010; Stefanescu et al. 2020; Torre et al. 2020). Thus, overall annual differences in densities reflected actual temporal changes in small mammal availability to buzzards. Species sampled in the study area were white-toothed shrew (Crocidura russula), Algerian mouse (Mus spretus), wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus), Yellow-necked mouse (Apodemus flavicollis), and bank vole (Myodes glareolus). The species with higher densities were shrew, Algerian mouse, and wood mouse (see “Results”). Despite other small mammal species being present in the area, these three species were considered as keystone prey, representing the bulk of the diet for other generalist forest-open predators in the study area (70–75% of occurrence among all small mammals in common genet and barn owl diets) (Torre et al. 2018). We performed GLMM models with negative binomial error (to avoid overdispersion (Zeileis et al. 2008) to test whether the relative density of the three most abundant species of small mammals was explained by habitat categorization (forests and shrublands–grasslands), and a visual inspection of data was used in the case of the two rarest species. Sampling station was added to the models as a random factor.

To assess whether population relative densities of the five species of small mammals were synchronous over the years (i.e., their fluctuations were correlated), we compute community-wide synchrony and its significance via Monte Carlo randomizations using the R-package ‘synchrony’. Values of community-wide synchrony range between 0 and 1, and they would have the maximum value when all species fluctuate in parallel. The Monte Carlo randomizations are performed by shuffling the columns of the community matrix independently, and randomizations also return the mean correlation between the columns of the matrix.

Capture–recapture modelling of local survival

We modelled the annual probabilities of buzzard survival and fidelity to the wintering area (i.e., local survival) using capture–recapture models for open populations (Lebreton et al. 1992). We created annual encounter histories for every marked bird in which individuals captured/resighted during the winter period (October year t to February year t + 1) were pooled in a single occasion, resulting in 347 encounters of 147 marked birds. We first tested the goodness-of-fit of the general Cormack–Jolly–Seber model (CJS hereafter) by age at first capture (first winter vs older birds) and residency status groups (i.e. residents and wintering birds) using the program U-CARE (Choquet et al. 2009). Then, using program MARK (White and Burnham 1999) and starting with a general model with survival probabilities varying over time between residency status groups (but in parallel between age classes within a group), we first tested the effect of time and residency status on detection probability. Once the best structure for this parameter was selected, we modelled local survival. We evaluated if local survival was related to residency status, age, time and/or prey abundance using the mean density of small mammals in the area in late autumn as a temporal covariate. In particular, we tested nine covariates accounting for annual variability of small mammal density in the study area: (a) for each of the five species; (b) for shrubland species (C. russula and M. spretus); (c) for shrubland species plus A. sylvaticus, which occupies both habitats; (d) for species occupying forests (A. flavicollis and M. glareolus); (e) finally for all the species together.

Model selection was based on Akaike Information Criterion corrected by sample size (Burnham and Anderson 2002). Models differing by < 2 AICc points were considered equivalent and the Akaike weights were calculated as an index of model plausibility over the models performed. The statistical significance of temporal covariates was assessed using analysis of deviance with a Fisher–Snedecor distribution (ANODEV; (Grosbois et al. 2008). The percentage of temporal variation in local survival explained by densities of small mammals R2 was calculated by comparing deviance of models with covariate (Devdens) to the constant (Devconst) and the time-dependent models (Devt), such that:

Results

During the study period (autumn 2009-autumn 2019) we trapped 827 small mammal individuals of five species. The white-toothed shrew was the more abundant (36.2%), followed by wood mouse (33.4%) and Algerian mouse (22.7%). Bank vole and Yellow-necked mouse represented < 6% of captures. Mean weight for the trapped individuals over the study was 8.1 g (SD = 1.2) for shrews, 13.8 g (SD = 3.5) for Algerian mice, 24.2 g (SD = 6.5) for wood mice, 26.4 g (SD = 3.5) for yellow-necked mice and 23.9 g (SD = 3.8) for bank voles. Relative densities of small mammals estimated during late autumn over 104 sampled trapping occasions from 2009 to 2019 varied differently for each species over the years (Fig. 2). On average, total densities were higher in shrublands than in forests (mean = 21.6, S.D. = 6.6; mean = 5.3, S.D. = 5.3, respectively) (Fig. 3). Species were assigned to preferred habitats considering the specific responses to land-use change in the study area (Torre et al. 2015): white-toothed shrew and Algerian mouse mostly inhabited open habitats, whereas wood mouse, Yellow-necked mouse, and bank voles were forest species. GLMM models showed that relative densities of white-toothed shrews and Algerian mice were positively influenced by shrublands (R2 = 0.51 and R2 = 0.28, respectively), whereas the density of wood mice was not higher in this habitat (R2 = 0.03). Bank voles and yellow-necked mice were only trapped in forests. AIC values showed that GLMMs with negative binomial showed better fit than Poisson, and solved the problem of overdispersion in all cases (Supplementary Material, Table S1). Fluctuations of population density over the years for the five species of small mammals were not significantly correlated (community synchrony: 0.3535; mean pairwise correlation: 0.07458; community synchrony p value (one-tailed test [greater]): 0.1667).

Annual variability (2009–2019) of the relative density of the five species of small mammals for each habitat categorization: a only shrublands (inset show densities separately for Crocidura and Mus); b shrubland and forest habitats, corresponding to A. sylvaticus; and c only forests (inset shows densities separately for A. flavicollis and M. glareolus). All panels have the same scales except inset for forest species (maximum relative density = 1.5). Panels show annual values averaged for the eight trapping stations

Mean relative density (with ± S.D.) of each small mammal species at forest and shrubland sampling stations in the study area during 2009–2019 (see Fig. 1). Apo_fla Yellow-necked mouse, Apo_syl wood mouse, Cr_rus white-toothed shrew, Mus_spr Algerian mouse, Myo_gl bank vole

Capture-mark recapture modelling of buzzard survival

During the study, we recorded 5488 observations of marked birds that could be identified. From these, 2572 resightings corresponded to the wintering sampling periods (winter mean number of resights = 234; range = 55–386). Most resightings (84%) corresponded to resident birds, since they were observed more often within each wintering sampling period.

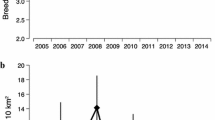

The overall test of goodness-of-fit of the CJS model was not statistically significant indicating that the CJS model by residency and age groups can be used as a starting model (\({\chi }_{50}^{2}\)= 29.90, p = 0.989). Lack of a statistically significant transient effect suggested that the frequency of birds just migrating through the study area was low and that our assignment of residency status was not biased. Model selection indicated that models with constant resighting probabilities or resighting probabilities depending on the wintering status of birds were equally supported and preferred over models including temporal variation (Table 1). In fact, both groups of birds showed similar resighting probabilities, being slightly higher for residents (0.83, 95% CI = 0.72–0.90) than for wintering visitors (0.79, 95% CI = 0.69–0.87) (Model 4, Table 1). A model considering a constant survival for older residents (model 13) was not retained. Both constant and group dependent resight formulations were used to model local survival, and, in this case, models including additive differences between first winter and older residents and wintering visitors were preferred (Table 1). Mean local survival of resident buzzards (1st winter residents = 0. 68, 95% CI = 0.50–0.81; older residents = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.72–0.87) was higher than mean local survival of wintering birds (1st winter visitors = 0.50, 95% CI = 0.37–0.63; older visitors = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.59–0.74) (Model 11, Table 1). Models with constant survival during the study period were better ranked than models with full temporal variations. However, up to 52% of temporal variation in local survival probabilities was explained by the total density of shrubland small mammal species (M. spretus and C. russula) during autumn (Table 1, Fig. 4). Best models included the effect of the small mammal density covariates, which were statistically significant when we tested the density of the species of open shrubland habitats, but also for the species of mixture habitats and the total density of all species. The covariate was not significant when the density of single small mammal species or only the density of forest species was considered (see Table 1). Buzzards have been described as predators in open habitats. However, our study area is mostly covered by forests, and observing buzzards hunting in this habitat is challenging. Our results confirm that buzzards preferred hunting in shrublands and avoided forests. Local survival and small mammal density showed a positive relationship (see Fig. 4 for the best model).

Left panels: annual estimates (and 95% CI) of local survival probabilities of the first winter and older resident (circles) and wintering (squares) buzzards from winter 2009–10 until winter 2019–20 (Model Survival (age + g + time) Resight (.), not shown in Table 1 since ΔAICc = 9.11). The red dashed line indicates the estimated relative density of shrubland small mammals (M. spretus and C. russula) during the previous autumn. Right panels: relationship between annual estimates of local survival probabilities of the first winter and older resident (circles) and wintering (squares) buzzards and the annual density of small mammals

Discussion

Testing how stochastic fluctuations of prey densities influence survival of long-lived predators is challenging mainly due to the difficulties for collecting robust data simultaneously for prey and predators at suitable spatio-temporal scales (Oro and Furness 2002; Karell et al. 2009; Margalida et al. 2014). Yet, for non-colonial long-lived birds, sample sizes tend to be small and the power to assess the ecological processes influencing their survival is limited. From a methodological point of view, we cannot be completely certain about the residency status of all marked birds in the sample, although the intense monitoring of breeding territories may have greatly reduced this potential bias. Despite these constraints, we found that the annual variability in the density of small mammals (mice, shrews, and voles), which are the main prey of buzzards in this region during winter (Mañosa and Cordero 1992), influenced their local survival at the wintering area. As expected for long-lived raptors, juvenile birds showed lower local survival than older birds (Kenward et al. 1999; Morrison 2003; Sanz-Aguilar et al. 2015). While the estimate of local survival for resident birds may be close to the actual survival value (especially for adults that seldom emigrate to other breeding areas), the local survival for wintering birds likely reflects their tendency to return to the wintering area, which is lower than for residents. We cannot disentangle whether this lower survival is only due to a higher permanent dispersal of wintering birds (which in models is confounded with mortality) or there is also actual higher mortality, both processes influenced by competition with residents and likely with other similar predators. At the study wintering area, residents (i.e., breeding adults and local-born juveniles) and wintering visitors coming from abroad co-occur and buzzards triple in density (Grajera and Carbonell 2017). Whatever the reason for this lower survival, we show that wintering buzzards would be more philopatric to the wintering area when they found high prey densities that year, which likely reduces the strength of density-dependence (Oro et al. 2006; Ross et al. 2015; Radchuk et al. 2016). Furthermore, compared to the surrounding areas, annual rainfall here is higher (> 800 mm) and rainfall is associated with larger densities of small mammals (Diaz et al. 2010, p. 201). This likely increases habitat suitability of the study area for wintering buzzards over the years. For migratory animals, wintering areas are crucial for their survival and population dynamics, since winter is a particularly challenging season with harsher climatic conditions and higher competition for food (Grande et al. 2009; Hinnebusch et al. 2010; Wellicome et al. 2014; Sergio et al. 2014b; Baltag et al. 2018; Millon et al. 2019). Furthermore, studying winter survival of species having resident populations and migrant populations, such as buzzards, have great interest to assess the ecological and evolutionary effects of a warming climate and the shift in distribution ranges on wintering strategies (Paprocki et al. 2014; Martín et al. 2014; Sanz-Aguilar et al. 2015). It remains unknown the consequences of the different local survival for resident and wintering birds for their population dynamics, but it is expected that these dynamics are influenced by environmental stochasticity and the changes caused in prey densities over the winter seasons (Sherry and Holmes 1995). Wintering birds are likely searching for areas where prey densities and chances for surviving are higher, but in these areas, intra- and interspecific competition maybe also larger (Johnson 2007). Small mammals are the main prey for a diverse community of predators in the study area, including other raptor species (both diurnal and nocturnal) and mesocarnivores (Torre et al. 2013). Furthermore, predation rates on small mammals change along environmental gradients, show spatial association but a small spatial overlap between species of predators, which suggests they avoid interspecific competition (Torre et al. 2013).

The population dynamics of the small mammal community shed light on the ecological and evolutionary demography of buzzards in wintering areas. First, not only the survival of juveniles is affected by prey density every winter, but also that of older birds, which should be more buffered against environmental stochasticity (Gamelon et al. 2017). As mentioned earlier, winter is the season when density-dependence is stronger due to the presence of individuals born in the last cohort and the occurrence of harsher climatic events (Sanz-Aguilar et al. 2015, 2016). Furthermore, we found that small mammals in the study area have asynchronous temporal dynamics, and none of the species, when considering their single fluctuations, explained part of the observed variability in survival. Total fluctuations of the more abundant species occupying open habitats, where buzzards are mostly observed while hunting in winter, are influencing local survival and the trend to return to the wintering area. Wintering buzzards take profit of the higher availability of shrews in autumn–winter (Torre et al. 2020), when the more widespread and abundant wood mouse is relatively scarce (Stefanescu et al. 2020). Further, buzzards surely benefitted from hunting more diurnal small mammals such as white-toothed shrew and Algerian mouse, which show polyphasic rhythm and diurnal activity, respectively, in winter (Palomo et al. 2009). This also suggests that buzzards preyed opportunistically on the commonest prey each winter and they do not target a single species despite their differences in body mass. Generalist predation may buffer the impact of resource unpredictability for pulsed and asynchronous prey dynamics, typical of small mammals in winter (Hanski et al. 1991; Yang et al. 2008; Fargallo et al. 2009). At the same time, our results suggest the capability of generalist predators to exert top-down forcing on lower trophic levels and community dynamics of their prey (Sergio et al. 2014a).

References

Badia-Boher JA, Sanz-Aguilar A, de la Riva M et al (2019) Evaluating European LIFE conservation projects: improvements in survival of an endangered vulture. J Appl Ecol 56:1210–1219. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13350

Baltag EŞ, Petrencu L, Bolboacă LE, Sfîcă L (2018) Common buzzards Buteo buteo wintering in Eastern Romania: habitat use and climatic factors affecting their abundance. Acta Ornithol 53:1–12. https://doi.org/10.3161/00016454AO2018.53.1.001

Brommer JE, Pietiäinen H, Kolunen H (2002) Reproduction and survival in a variable environment: ural owls (Strix Uralensis) and the three-year vole cycle. Auk 119:544–550. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/119.2.544

Burnham KP, Anderson DR (2002) Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. Springer Science and Business Media, New York

Choquet R, Lebreton J, Gimenez O et al (2009) U-CARE: utilities for performing goodness of fit tests and manipulating CApture–REcapture data. Ecography 32:1071–1074

Diaz M, Torre I, Arrizabalaga A (2010) Relative roles of density and rainfall on the short-term regulation of Mediterranean wood mouse Apodemus sylvaticus populations. Acta Theriol (warsz) 55:251–260. https://doi.org/10.4098/j.at.0001-7051.046.2009

Fargallo JA, Martínez-Padilla J, Viñuela J et al (2009) Kestrel-prey dynamic in a Mediterranean region: the effect of generalist predation and climatic factors. PLoS One 4:e4311. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004311

Frederiksen M, Edwards M, Richardson AJ et al (2006) From plankton to top predators: bottom-up control of a marine food web across four trophic levels. J Anim Ecol 75:1259–1268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01148.x

Gamelon M, Grøtan V, Nilsson ALK et al (2017) Interactions between demography and environmental effects are important determinants of population dynamics. Sci Adv 3:e1602298. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1602298

Genovart M, Sanz-Aguilar A, Fernandez-Chacon A et al (2013) Contrasting effects of climatic variability on the demography of a trans-equatorial migratory seabird. J Anim Ecol 82:121–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2012.02015.x

Graham IM, Redpath SM, Thirgood SJ (1995) The diet and breeding density of Common Buzzards Buteo buteo in relation to indices of prey abundance. Bird Study 42:165–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063659509477162

Grajera J, Carbonell F (2017) Seguiment de la miloca (Buteo buteo) a la Serralada Litoral Central. In: III Trobada d’Estudiosos de la Serralada Litoral Central i VII del Montnegre i el Corredor. Diputació de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, pp 274–286

Grande JM, Serrano D, Tavecchia G et al (2009) Survival in a long-lived territorial migrant: effects of life-history traits and ecological conditions in wintering and breeding areas. Oikos 118:580–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17218.x

Grosbois V, Gimenez O, Gaillard J-M et al (2008) Assessing the impact of climate variation on survival in vertebrate populations. Biol Rev 83:357–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00047.x

Hanski I, Hansson L, Henttonen H (1991) Specialist predators, generalist predators, and the microtine rodent cycle. J Anim Ecol 60:353–367. https://doi.org/10.2307/5465

Hanski I, Turchin P, Korpimäki E, Henttonen H (1993) Population oscillations of boreal rodents: regulation by mustelid predators leads to chaos. Nature 364:232–235. https://doi.org/10.1038/364232a0

Harris MP, Anker-Nilssen T, Mccleery RH et al (2005) Effect of wintering area and climate on the survival of adult Atlantic puffins Fratercula arctica in the eastern Atlantic. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 297:283–296

Hinnebusch DM, Therrien J-F, Valiquette M-A et al (2010) Survival, site fidelity, and population trends of American kestrels wintering in Southwestern Florida. Wilson J Ornithol 122:475–483. https://doi.org/10.1676/09-170.1

Johnson MD (2007) Measuring habitat quality: a review. Condor 109:489–504. https://doi.org/10.1093/condor/109.3.489

Karell P, Ahola K, Karstinen T et al (2009) Population dynamics in a cyclic environment: consequences of cyclic food abundance on tawny owl reproduction and survival. J Anim Ecol 78:1050–1062. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01563.x

Kenward RE, Marcström V, Karlbom M (1999) Demographic estimates from radio-tagging: models of age-specific survival and breeding in the goshawk. J Anim Ecol 68:1020–1033. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2656.1999.00347.x

Klaassen RHG, Hake M, Strandberg R et al (2014) When and where does mortality occur in migratory birds? Direct evidence from long-term satellite tracking of raptors. J Anim Ecol 83:176–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12135

Lande R, Engen S, Sæther B-E (2003) Stochastic population dynamics in ecology and conservation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Lebreton JD, Burnham KP, Clobert J, Anderson DR (1992) Modeling survival and testing biological hypothesis using marked animals: a unified approach with case studies. Ecol Monogr 62:67–118. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937171

Mañosa S, Cordero PJ (1992) Seasonal and sexual variation in the diet of the common buzzard in northeastern Spain. J Raptor Res 26:235–238

Margalida A, Colomer MÀ, Oro D (2014) Man-induced activities modify demographic parameters in a long-lived species: effects of poisoning and health policies. Ecol Appl 24:436–444. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0414.1

Martín B, Onrubia A, Ferrer MA (2014) Effects of climate change on the migratory behavior of the common buzzard Buteo buteo. Clim Res 60:187–197. https://doi.org/10.3354/cr01233

Martínez-Abraín A, Tavecchia G, Regan HM et al (2012) Effects of wind farms and food scarcity on a large scavenging bird species following an epidemic of bovine spongiform encephalopathy. J Appl Ecol 49:109–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.02080.x

McClure CJW, Brown JL, Schulwitz SE et al (2020) Demography of a widespread raptor across disparate regions. Ibis N/a: https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12916

Mihoub J-B, Gimenez O, Pilard P, Sarrazin F (2010) Challenging conservation of migratory species: Sahelian rainfalls drive first-year survival of the vulnerable Lesser Kestrel Falco naumanni. Biol Conserv 143:839–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2009.12.026

Millon A, Petty SJ, Little B et al (2014) Dampening prey cycle overrides the impact of climate change on predator population dynamics: a long-term demographic study on tawny owls. Glob Change Biol 20:1770–1781. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12546

Millon A, Danovaro C, Printemps T et al (2019) Disentangling the effects of environmental conditions on wintering and breeding grounds on age-specific survival rates in a trans-Saharan migratory raptor. J Avian Biol 50:e02233. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.02233

Morrison JL (2003) Age-specific survival of Florida’s Crested Caracaras. J Field Ornithol 74:321–330. https://doi.org/10.1648/0273-8570-74.4.321

Newton I, McGrady MJ, Oli MK (2016) A review of survival estimates for raptors and owls. Ibis 158:227–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12355

Oro D, Furness RW (2002) Influences of food availability and predation on survival of kittiwakes. Ecology 83:2516–2528

Oro D, Martínez-Abraín A, Paracuellos M et al (2006) Influence of density dependence on predator–prey seabird interactions at large spatio-temporal scales. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 273:379–383. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3287

Palomo LJ, Justo ER, Vargas JM (2009) Mus spretus (Rodentia: Muridae). Mamm Species 840:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1644/840.1

Pannekoek J, Van Strien AJ (2005) TRIM 3 manual. Trends and indices for monitoring data. CBS, Statistics Netherlands, Voorburg, Netherlands. http://www.ebcc.info/

Paprocki N, Heath JA, Novak SJ (2014) Regional distribution shifts help explain local changes in wintering raptor abundance: implications for interpreting population trends. PLoS One 9:e86814. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086814

Radchuk V, Ims RA, Andreassen HP (2016) From individuals to population cycles: the role of extrinsic and intrinsic factors in rodent populations. Ecology 97:720–732. https://doi.org/10.1890/15-0756.1

Reif V, Jungell S, Korpimaki E et al (2004) Numerical response of common buzzards and predation rate of main and alternative prey under fluctuating food conditions. Ann Zool Fenn 41:599–607

Ross BE, Hooten MB, DeVink J-M, Koons DN (2015) Combined effects of climate, predation, and density dependence on greater and lesser Scaup population dynamics. Ecol Appl 25:1606–1617. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-0582.1

Saether BE, Bakke O (2000) Avian life history variation and contribution of demographic traits to the population growth rate. Ecology 81:642–653

Sanz-Aguilar A, Béchet A, Germain C et al (2012) To leave or not to leave: survival trade-offs between different migratory strategies in the greater flamingo. J Anim Ecol 81:1171–1182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2012.01997.x

Sanz-Aguilar A, De Pablo F, Donázar JA (2015) Age-dependent survival of island vs. mainland populations of two avian scavengers: delving into migration costs. Oecologia 179:405–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-015-3355-x

Sanz-Aguilar A, Igual JM, Tavecchia G et al (2016) When immigration mask threats: the rescue effect of a Scopoli’s shearwater colony in the Western Mediterranean as a case study. Biol Conserv 198:33–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.03.034

Sergio F, Tavecchia G, Blas J et al (2011) Variation in age-structured vital rates of a long-lived raptor: implications for population growth. Basic Appl Ecol 12:107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2010.11.004

Sergio F, Schmitz OJ, Krebs CJ et al (2014a) Towards a cohesive, holistic view of top predation: a definition, synthesis and perspective. Oikos 123:1234–1243. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.01468

Sergio F, Tanferna A, Stephanis RD et al (2014b) Individual improvements and selective mortality shape lifelong migratory performance. Nature 515:410–413. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13696

Sherry TW, Holmes RT (1995) Summer versus winter limitation of populations: what are the issues and what is the evidence. In: Finch Martin DMTE (ed) A synthesis and review of critical issues. ecology and management of neotropical migratory birds. Oxford University Press, pp 85–120

Stefanescu C, Soldevila A, Gutiérrez C et al (2020) Explosions demogràfiques de l’eruga peluda del suro, Lymantria dispar (Linnaeus, 1758), als boscos del Montnegre el 2019 i 2020: possibles causes, impactes i idoneïtat dels tractaments per combatre la plaga. Butlletí Inst Catalana Història Nat 84:267–279

Tavecchia G, Adrover J, Navarro AM, Pradel R (2012) Modelling mortality causes in longitudinal data in the presence of tag loss: application to raptor poisoning and electrocution. J Appl Ecol 49:297–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.02074.x

Torre I, Arrizabalaga A, Freixas L et al (2013) Using scats of a generalist carnivore as a tool to monitor small mammal communities in Mediterranean habitats. Basic Appl Ecol 14:155–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2013.01.005

Torre I, Gracia-Quintas L, Arrizabalaga A et al (2015) Are recent changes in the terrestrial small mammal communities related to land use change? A test using pellet analyses. Ecol Res 30:813–819. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-015-1279-x

Torre I, Raspall A, Arrizabalaga A, Díaz M (2018) SEMICE: an unbiased and powerful monitoring protocol for small mammals in the Mediterranean Region. Mamm Biol 88:161–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2017.10.009

Torre I, Bastardas-Llabot J, Arrizabalaga A, Díaz M (2020) Population dynamics of small endotherms under global change: greater white-toothed shrews Crocidura russula in Mediterranean habitats. Sci Total Environ 705:135799

Wellicome TI, Fisher RJ, Poulin RG et al (2014) Apparent survival of adult burrowing owls that breed in Canada is influenced by weather during migration and on their wintering grounds. The Condor 116:446–458. https://doi.org/10.1650/CONDOR-13-161.1

White GC, Burnham KP (1999) Program MARK: survival estimation from populations of marked animals. Bird Study 46:S120–S139

Yang LH, Bastow JL, Spence KO, Wright AN (2008) What can we learn from resource pulses. Ecology 89:621–634. https://doi.org/10.1890/07-0175.1

Zeileis A, Kleiber C, Jackman S (2008) Regression models for count data in R. J Stat Softw. 27: 1–25. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v027.i08

Zuberogoitia I, Martínez JA, Zabala J et al (2005) Sexing, ageing and moult of Buzzards Buteo buteo in a southern European area. Ringing Migr 22:153–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/03078698.2005.9674324

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all the numerous people that helped out with fieldwork. We are grateful to the landowners and farmers who facilitate logistics, and to Raül Aymí and Santi Mañosa (both of ICO), and Monica Alonso and Héctor Andino for their support. Meritxell Genovart provided valuable comments on early drafts. This is a contribution to the BiBio project (Bioindicators and Biodiversity) by the Natural Sciences Museum of Granollers. The Associated Editor, Rob Robinson and one anonymous reviewer helped for improving a previous draft of the MS.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Regional conservation agencies (Diputació de Barcelona, Dept. de Territori i Sostenibilitat -Generalitat de Catalunya) provided financial support to SEMICE. JG funded on his own all fieldwork research on buzzards. ASA was supported by a Ramón y Cajal fellowship of the Spanish Ministry of Science (RYC-2017-22796).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DO, JG and IT conceived the study. JG and IT performed the fieldwork. FC curated the dataset. DO, ASA and IT analysed the data. DO wrote the manuscript; other authors provided editorial advice.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Permits–All work adheres to the Generalitat de Catalunya guidelines for the Use of Animals in Research and was conducted after ethical approval by all conservation agencies responsible for ethical wildlife research.

Additional information

Communicated by Robert L Thomson.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oro, D., Sanz-Aguilar, A., Carbonell, F. et al. Multi-species prey dynamics influence local survival in resident and wintering generalist predators. Oecologia 197, 437–446 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-021-05042-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-021-05042-2