Abstract

Purpose

This study evaluated the reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Japanese version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-ELD14 and measured the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of elderly Japanese patients with cancer aged ≥ 60 and ≥ 70 years.

Methods

The study recruited elderly Japanese patients with cancer aged ≥ 60 (≥ 70) years (n = 1803 [n = 1236]). The EORTC QLQ-ELD14 was evaluated for reliability, validity, responsiveness, and correlations of changes in score between the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and the EORTC QLQ-C30 before and after the commencement of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

In both age groups, the proportion of missing items was low (< 3%). Cronbach’s α was good at ≥ 0.70, except for two of the seven items. All the intraclass coefficient constants were good at ≥ 0.70. The concurrent validity was good but correlation with the EORTC QLQ-C30 was not strong, except for the hypothesis items. Regarding the assessment of responsiveness, only one item (“maintaining purpose”) of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 worsened (− 6.14 ± 29.20, standard response of mean > 0.2) after the commencement of the COVID-19 pandemic. The changes in score between the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and the “global health status/QOL” and “summary score” of the EORTC QLQ-C30 had moderate-to-high negative correlations for all items, except two. Hypotheses to evaluate construct validity were accepted at 90%, while responsiveness was accepted at 80%.

Conclusion

The Japanese version of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 questionnaire appears to have acceptable reliability, validity, and responsiveness to evaluate HRQOL in elderly Japanese people with cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in elderly populations worldwide, particularly in developed countries, owing to their proportionately large aging population (Pilleron et al. 2019). Age is the strongest risk factor for the development of cancer. In comparison to younger people with cancer, older people with cancer tend to prefer a better health-related quality of life (HRQOL) over an increased span of life (Tester et al. 2004). Moreover, the concept of HRQOL in elderly patients is not linked to any specific medical condition and is a broad concept (Wilson and Cleary 1995). In an original study on HRQOL, Wilson and Cleary (1995) divided health outcomes into the following five levels: biological and physiological factors, symptoms, functioning, general health perceptions, and overall quality of life. They determined that, at each level, there are an increasing number of traditional clinical variables that cannot be controlled by clinicians or the health care system (Wright et al. 2005).

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) is the primary questionnaire used to evaluate HRQOL in cancer patients worldwide (Aaronson et al. 1993). However, elderly individuals with cancer (aged ≥ 70 years) have a different HRQOL profile compared with other age groups, and the EORTC QLQ-C30 does not address their specific needs (Fitzsimmons et al. 2009; Johnson et al. 2010). There are significant differences in EORTC QLQ-C30 responses according to age (Hjermstad et al. 1998; Michelson et al. 2000; Schwarz and Hinz 2001). The EORTC QLQ-ELD15 and its revised version (ELD14) were developed to complement the QLQ-C30 and to account for age-specific issues that are of relevance and importance for older cancer patients (Wright et al. 2005); these two questionnaires help assess the HRQOL of elderly people with cancer (Johnson et al. 2010). Studies using the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 were conducted with patients with cancer from 10 countries (n = 518) and showed good reliability and validity (Wheelwright et al. 2013). Moreover, it was recently validated in Korea (Goo et al. 2017), Poland (Wrazen et al. 2014), Spain (Arraras et al. 2019), and Chile (Lorca et al. 2021).

The term “elderly” does not have a clear definition, and it is important to assess the definition individually. The Korean version of the scale was validated for reliability and validity in elderly patients, ≥ 60 years, with cancer (Goo et al. 2017). From the societal point of view, the age of retirement entitlement in elderly people is approximately 55–70 years (World Health Organization 2021). Japanese people retire at approximately 60 years in most companies, but in recent years the retirement age has increased. The World Health Organization (WHO) described aging populations as those aged ≥ 65 years (World Health Organization 2021). In politics, the definition applies to ages ranging from 70 or 75 years and above. The EORTC QLQ-ELD15 paper described the definition of elderly as age ≥ 70 years as one of the potential limitations of the module (Johnson et al. 2010). We aimed to assess biological age rather than chronological age. A thorough search of the literature revealed that there were no studies evaluating HRQOL changes in Japanese people with cancer, especially among the elderly, using the EORTC QLQ-ELD14. Therefore, we evaluated the psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 with the aim of confirming its applicability to Japanese individuals with cancer ≥ 60 and ≥ 70 years of age and of comparing the results to the Korean EORTC QLQ-ELD14 study.

The COVID-19 pandemic had not begun when we commenced this study. After the pandemic began in December 2019, we were unsure of the feasibility of the investigation, but we soon found it to be a valuable opportunity to evaluate how HRQOL changes in people with cancer.

The pandemic has had a significant health impact on the elderly. Consequently, we also attempted to assess the changes in the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 score due to the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic, in elderly individuals with cancer. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the HRQOL of elderly people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, using the EORTC QLQ-ELD14.

Participants and methods

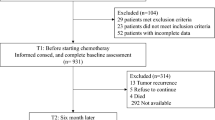

Participants

Of the 4166 cancer patients (the five most common cancer types in the Japanese population being colorectal, gastric, lung, breast, and prostate) with data in the hospital-based cancer registry (registered from 2013 at Kyushu University Hospital), 1803 (43.3%) with data from June 2019 to March 2021 were included in this study. Initially, we met patients at outpatient clinics whenever possible and asked them to complete the questionnaires at home and return them, but after the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted the survey by mail. Eligibility criteria included (i) a diagnosis of primary cancer, (ii) age ≥ 60 years, (iii) physician’s approval, (iv) mentally healthy as far as the physicians were aware, and (v) ability to complete the questionnaire. Secondary cancers were excluded from the study.

Questionnaires

EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0)

The 30-item EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) assesses the functional status and symptoms of cancer patients and contains the following items: a “global health status/QOL” scale, five functional scales/items (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social), and nine symptom scales/items (fatigue, nausea, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, anorexia, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulties) (Kobayashi et al. 1998; Schwarz and Hinz 2001; Arraras et al. 2019). “Global health status/QOL” questions include the following: “How would you rate your overall health during the past week?” and “How would you rate your overall quality of life during the past week?” A mean difference of ≥ 10 points is regarded as clinically meaningful for all EORTC QLQ-C30 scales (Osoba et al. 1998). Total scores range from 0 to 100. Higher scores on the “global health status/QOL” and functional scales indicate better functioning. Higher scores on the symptom scales/items indicate more severe problems. The EORTC QLQ-C30 “summary score” is calculated from the mean of 13/ 15 item scores of the QLQ-C30 scales; except the items “global health status/QOL”, and “financial difficulties” on the symptom scales/items (Kasper 2020). In recent years, the EORTC QLQ‐C30 “summary score” was indicated to have the highest prognostic significance in predicting the survival of patients with cancer compared with individual item and scale scores.

EORTC QLQ-ELD14

The Japanese version of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 was authorized by the EORTC Quality of Life Group Translation Unit (Fayers and Machin 2000) and was translated in accordance with the EORTC quality of life group translation procedure (Young et al. 1999). The translated version of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 was then pilot-tested with 10 patients with cancer. Patients were asked if they found any of the questions difficult, confusing, upsetting, and so forth. Based on these suggestions, the questionnaire was modified. The EORTC QLQ-ELD14 was subjected to a standard forward–backward translation process. Two translators translated the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 into Japanese with forward translations. After that, two professional translators translated the Japanese version of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 back into English. The translation report was then reviewed by the EORTC translation coordinator. The 14-item QLQ-ELD14 is designed to assess the HRQOL of elderly individuals with cancer, complementing the QLQ-C30. The QLQ-ELD14 has the following two functional scales: “maintaining purpose” (2 items) and “family support” (1 item); it also has five multi-item symptom scales: “mobility” (3 items), “worries about others” (2 items), “future worries” (3 items), “burden of illness” (2 items), and “joint stiffness” (1 item) (Wheelwright et al. 2013). Total scores range from 0 to 100. Higher scores on the functional scales indicate better functioning. Higher scores on the symptom and single-item scales indicate more severe problems.

G8 frailty screening tool

The G8 was developed for elderly individuals with cancer (Bellera et al. 2012). It assesses age, appetite changes, weight loss, mobility, neuropsychological problems, body mass index, medication intake, and self-reported health, by single-item scales. Total scores range from 0 (poor score) to 17 (good score). Higher scores indicate a “not at all impaired” status, with a score cut-off for potential frailty of ≤ 14 (Mohile et al. 2018).

Analysis

First, to establish a 95% confidence interval of the estimated proportion within ± 2.5%, it was necessary to collect data from 1600 elderly people. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze socio-demographic and clinical data.

We followed the EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual (Osoba et al. 1998; Fayers and Machin 2000; Goo et al. 2017). For missing items, a straightforward method used by many HRQOL instruments for imputing items from multi-item scales was used as following: if the participant had answered at least half of the items from the scale, it was assumed that the missing items would have values equal to the average of those items that had been answered by that particular respondent. Moreover, we used the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist (Mokkink et al. 2018a, b).

Reliability

The reliability domain consists of the following three measurement properties: (i) internal consistency, (ii) reliability, and (iii) measurement error. First, Cronbach α was used to assess the level of reliability of internal consistency, and α ≥ 0.7 was considered statistically significant (Cronbach 1951). Furthermore, it indicates the level of internal consistency with respect to the specific sample. Second, for the test–retest analysis, conventionally, an intraclass coefficient constant (ICC) of ≥ 0.70 was considered sufficient (Shrout and Fleiss 1979). Third, measurement error refers to the systematic and random error in an individual patient’s score that is not attributable to true changes in the construct being measured; the statistic used to assess measurement error was the smallest detectable change (SDC) (Fayers and Machin 2000). It is directly related to the standard error of measurement (SEM). Changes within the SDC, and smaller than the SDC, were attributed to measurement error, and changes outside the SDC, and larger than the SDC, were considered to be real changes in individual patients. SEM is a measure of how much the measured test scores are spread around a “true” score. The SDC is a measure of the variation in a scale due to measurement error. Thus, a change score can only be considered to represent a real change if it is larger than the SDC. It is the same as a minimum detectable change.

Validity

Validity was measured as construct and criterion validity.

Although we first attempted to use factor analysis, we were unable to do so because the structure of the items was different. We performed multi-trait analysis (Pearson’s correlation uses parametric equivalents to evaluate the linear relationship between two continuous variables; 0–100) to assess structural validity. Convergent validity was considered when an item correlated highly with its own hypothesized scale (correlation ≥ 0.40; corrected for overlap). Discriminant validity was considered when an item did not correlate highly with the scales it was not a part of. Discriminant validity was supported when the correlation between an item and its hypothesized scale (corrected for overlap) was > 2 standard errors higher than its correlation with other scales.

We developed the following hypotheses to evaluate construct validity:

-

(1)

The direction and magnitude of differences in the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 between groups: known-group comparisons.

-

(a)

Disease stage; patients with stage 0–II would have significantly superior scores compared with those in stages III–IV; "Worries about others” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14.

-

(b)

Comorbidities; patients with no comorbidities would have significantly superior scores than those with > 1 comorbidity; “Mobility”, “Burden of illness”, “Joint stiffness”.

-

(c)

G8; Patients who were not frail would have significantly superior scores compared to frail patients; “Mobility”, “Worries about others”, “Future worries”, and “Burden of illness”.

-

(a)

-

(2)

Correlations with instruments measuring similar constructs; criterion convergent validity

-

(a)

Between “Mobility” on EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and “Physical functioning” on the EORTC QLQ-C30, there would be a high negative correlation of ≥ − 0.70.

-

(b)

Between “Mobility” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and “Role functioning” on the EORTC QLQ-C30, there would be a moderate-to-high negative correlation of ≥ − 0.40

-

(c)

Between “Mobility” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and “Fatigue” on the EORTC QLQ-C30, there would be a moderate-to-high positive correlation of ≥ 0.40.

-

(d)

Between “Future worries” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and “Emotional functioning” on the EORTC QLQ-C30, there would be a moderate-to-high negative correlation of ≥ − 0.40.

-

(e)

Between “Future worries” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and “Social functioning” on the EORTC QLQ-C30, there would be a moderate-to-high negative correlation of ≥ − 0.40.

-

(f)

Between “Burden of illness” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and “Social functioning” on the EORTC QLQ-C30, there would be a moderate-to-high negative correlation of ≥ − 0.40.

-

(g)

Between “Burden of illness” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and “Financial difficulties” on the EORTC QLQ-C30, there would be a moderate-to-high positive correlation of ≥ 0.4.

-

(a)

Hypotheses to evaluate construct validity are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The results were confirmed if 75% of the results were in accordance with the hypotheses and the testing and responsiveness results.

The hypotheses about discriminative or known group validity were made about the expected differences in EORTC QLQ-ELD14 scores between patients according to Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) stage, comorbidity, and G8 scores (a cut-off for potential frailty), by known group comparisons. Known group comparisons were assessed by comparing elderly people with cancer using independent t tests.

Concurrent validity was analyzed using the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 scale, and the correlation coefficient between single items, to evaluate the capabilities of each scale and of single items. In addition, criteria-related validity was assessed using a Pearson correlation analysis between each scale of the EORTCQLQ-ELD14 and EORTCQLQ-C30. These scales correlated weakly (only “maintaining purpose” on the EORTCQLQ-ELD14 did not correlate significantly with most of the items on the EORTC QLQ-C30). We hypothesized with respect to the expected magnitude and orientation of the relationship between the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and EORTC QLQ-C30 subscales in Supplementary Table S1.

Responsiveness

The hypotheses used to evaluate responsiveness are shown in Supplementary Table S2. The results were confirmed if 75% of the results were in accordance with the hypotheses, and the testing and responsiveness of the results.

The hypotheses to evaluate responsiveness were as follows:

-

(1)

Responsiveness to change on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 would worsen after the commencement of the COVID-19 pandemic; SRM > 0.2. Four of Five hypotheses were in accordance with the hypothesis. Only “Future worries” on EORTC QLQ-ELD14 was not in accordance with the hypotheses.

-

(a)

“Maintaining of purpose” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14.

-

(b)

“Future worries” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14.

-

(a)

-

(2)

Correlations with changes in instruments measuring similar constructs. All three results were in accordance with the hypotheses.

-

(a)

Between “mobility” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and “Global health stats QOL” and “Summary Score” on the EORTC QLQ-C30, there would be a moderate-to-high negative correlation of ≥ − 0.40.

-

(b)

Between “future worries” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and “Global health stats QOL” and “Summary Score” on the EORTC QLQ-C30, there would be a moderate-to-high negative correlation of ≥ − 0.40.

-

(c)

Between “burden of illness” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and “Global health stats QOL” and “Summary Score” on the EORTC QLQ-C30, there would be a moderate-to-high negative correlation of ≥ − 0.40.

-

(a)

Responsiveness was evaluated as standardized effect size (ES) and standardized response mean (SRM) (Beaton et al. 2001), using paired t-tests to compare the changes in the scores from before and after the commencement of the COVID-19 pandemic. The ES was determined by calculating the difference between the means before and after treatment and dividing it by the standard deviation of the same measure before treatment. The ES is sensitive to between-subject variability, and SRM is sensitive to within-subject variability. The larger the SRM, the greater the responsiveness. An SRM of 0.20 was considered small, 0.50 as moderate, and 0.80 or higher as large. Next, correlations between changes in the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and EORTC QLQ C30 scales were calculated with Pearson’s correlations.

All tests were two-tailed. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed with IBM SPSS statistics version 26.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyushu University (2019-450). All persons gave informed consent prior to inclusion in the study. Prior to the study, participants were asked to sign a written informed consent form to confirm their willingness to participate in this study.

Results

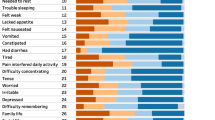

The proportion of missing items on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 was 0.3–2.3% for those aged ≥ 60 years and 0.3–2.0% for those aged ≥ 70 years. The highest scored item was item number 12 (Have you felt motivated to continue with your normal hobbies and activities?) in “maintaining of purpose”. Missing data of < 5% for each item was considered acceptable (Fayers and Machin 2013).

Sociodemographic characteristics

The final analysis included 1803 individuals (aged 60 years and older) and 1236 individuals (aged 70 years and older). The characteristics of the participants are described in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 73.04 ± 6.858 in the ≥ 60 years age group and 76.55 ± 5.093 in the ≥ 70 years age group. There were 62.3% men (aged ≥ 60 years) and 65.8% men (aged ≥ 70 years). The period of diagnosis was 2–5 years in 46.4% of those aged ≥ 60 years and 45.6% in those aged ≥ 70 years.

Reliability

Internal consistency—Cronbach’s α

Table 2 shows that all the measures met the criteria for internal coherence (Cronbach α). Cronbach’s α for the scales was considered sufficient for all items with a value higher than 0.70; the exception was “maintaining purpose” with values of 0.65 in the ≥ 60 years age group and 0.62 in the ≥ 70 years age group, and “worries about others” with values of 0.67 in the ≥ 60 years age group and 0.68 in the ≥ 70 years age group.

Reliability—ICC

Table 3 shows the ICCs, and ICCs ≥ 0.7 were considered sufficient. ICCs for all the scales were above 0.80 in the ≥ 60 years age group and above 0.70 in the ≥ 70 years age group.

Measurement error-SEM

In the ≥ 60 years age group, the SDC scores ranged between 14.63 (mobility) to 29.84 (family support) on the 100 points scale. In the ≥ 70 years age group, the SDC scores ranged from 19.92 (mobility) to 36.80 (family support) on the 100 point scale. The SEMs/SDCs of all scales on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 were less than 1.

Validity

Construct validity

Construct validity is shown in Table 2. Item-own scale correlations were 0.48–0.78 for the ≥ 60 years age group and 0.45–0.78 for the ≥ 70 years age group. Additionally, item-other scale correlations were − 0.02–0.66 for the ≥ 60 years age group and 0.01–0.65 for the ≥ 70 years age group. Item 7, i.e., “worries about others” correlated more highly with items 8, 9, and 10 in the “future worries” scale.

Criterion validity

Hypotheses to evaluate construct validity (known group and concurrent validity) are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Regarding sufficient hypothesis testing for construct validity, 90% (9/10 items) of the results were in accordance with the hypotheses.

Two of three results were in accordance with the hypotheses. Only (a) Disease stage; patients with stage 0–II would have significantly superior scores than those in stages III–IV; "Worries about others” on EORTC QLQ-ELD14 was not in accordance with the hypotheses.

Known-group validity is presented in Tables 4 and 5. All scales having comorbidities and the G8, except the cancer stage of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14, showed known-group validity in both age groups. Analyses for the clinical cancer stage showed no significant differences among the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 scales. Patients with comorbidities had significantly worse EORTC QLQ-ELD14 scales except for the item “family support” in the ≥ 60 years age group. The ≥ 70 years age group had significantly inferior EORTC QLQ-ELD14 scales except for items such as “family support”, “worries about others”, and “future worries”. According to the G8, frail patients had significantly worse EORTC QLQ-ELD14 scale scores except for the item “family support” in both groups. The most significantly different scale was “burden of illness”, 19.42 ± 20.40 (not frail) vs. 37.89 ± 26.66 (frail) in the ≥ 70 years age group.

All seven results were in accordance with the hypotheses.

Table 6 shows the concurrent validity between the QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-ELD14. Convergent validity was established between “mobility” and “physical functioning” (r = − 0.797, ≥ 60 years age group; r = − 0.799, ≥ 70 years age group), between “mobility” and “role functioning” (r = − 0.797, 60 years age group; r = − 0.799, ≥ 70 years age group), and “mobility” and “fatigue” (r = − 0.688, 60 years age group; r = − 0.714, ≥ 70 years age group). Convergent validity was established between “future worries” and “emotional functioning” (r = − 0.514, ≥ 60 years age group; r = − 0.519, ≥ 70 years age group), and between “future worries” and “social functioning” (r = − 0.425, ≥ 60 years age group; r = − 0.419, ≥ 70 years age group).

Convergent validity was established between “burden of illness” and “social functioning” (r = − 0.498, ≥ 60 years age group; r = − 0.487, ≥ 70 years age group) and between “burden of illness” and “financial difficulties” (r = − 0.471, ≥ 60 years age group; r = − 0.444, ≥ 70 years age group).

Responsiveness (responsiveness to change analysis, RCA)

Hypotheses to evaluate responsiveness are presented in Supplementary Table S2. The results were confirmed if 75% of the results were in accordance with the hypotheses, and the testing and responsiveness results. Our hypotheses were accepted by approximately 80% (4/5 items). Responsiveness has been calculated and presented in Table 7. Our hypothesis was that “maintaining purpose” and “future worries” of the EORTC QLQ ELD-14 would worsen after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the pandemic. The indicators of responsiveness were calculated by ES and SRM. ES and SRM are unrelated to sample size. In our results, “maintaining purpose”, “future worries” (in both groups), and “burden of illness” (≥ 60 years age group) were significantly worse (p < 0.05), but ES and SRM were very low (SRM < 0.2) except for the item “maintaining purpose” (SRM = 0.21 for both groups).

The largest change in the responsiveness score was for the item “maintaining purpose” of the EORTC QLQ ELD-14; it worsened from 40.97 ± 24.26 to 35.00 ± 25.58 (change score: 6.14 ± 20.20) between before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (ES = 0.26, SRM = 0.21, p < 0.001). The responsiveness values of “global health status/QOL” on the EORTC QLQ-C30’s were SRM = 0.09 (≥ 60 years age group) and SRM = 0.13 (≥ 70 years age group), and these were smaller than the values of the item “maintaining purpose” of the EORTC QLQ ELD-14.

Table 8 shows the correlations with the changes between the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ- ELD14 after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, between the items. “Mobility” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 scale and “global health status/QOL” and “summary score” on the EORTC QLQ-C30 scale had a moderate-to-high negative correlation of ≥ − 0.40 (“global health status/QOL” − 0.730 and “summary score” − 0.571 for the ≥ 60 years age group; “global health status/QOL” − 0.599 and “summary score” − 0737 for the ≥ 70 years age group). Between the items “future worries” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and “global health status/QOL” and “summary score” on the EORTC QLQ-C30 there was a moderate-to-high negative correlation of ≥ − 0.40 (“global health status/QOL” − 0.550 and “summary score” − 0.489 for the ≥ 60 years age group; “global health status/QOL” − 0.502 and “summary score” − 0544 for the ≥ 70 years age group).

There was a moderate-to-high negative correlation (≥ − 0.40) between the “burden of illness” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and the “global health status/QOL” and “summary score” on the EORTC QLQ-C30 (“global health status/QOL” − 0.604 and “summary score” − 0.526 for the ≥ 60 years age group; “global health status/QOL” − 0.535 and “summary score” − 0.605 for the ≥ 70 years age group). Outside of our hypotheses, there was a moderate-to-high negative correlation (≥ − 0.40) between “worries about others” and “joint stiffness”, but not for “maintaining purpose” and “family support” of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and “global health status/QOL” and “summary score” of the EORTC QLQ-C30.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 for cross-cultural adaptation to elderly Japanese patients with cancer. The Japanese version of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 questionnaire is considered to be an acceptable, reliable, and effective tool for assessing the HRQOL of elderly Japanese patients with cancer. A study of the original version, EORTC QLQ-ELD15, described the definition of a study population aged ≥ 70 years as “elderly” as a potential limitation (Johnson et al. 2010). Moreover, the definition of “elderly” varies and it also differs on an individual level. Therefore, in this study, we grouped the study population to observe differences between those over 60 years of age and those over 70 years of age.

In our study, the five most common cancer types, among the Japanese population, were colorectal, gastric, lung, breast, and prostate. From a study of 10 countries with populations aged ≥ 70 years, Wheelwright et al. (2013) found additional types of cancer, including ovarian, hematological, and others. When compared to the Korean study (Goo et al. 2017), except for breast and prostate cancer, the clinical background of the patients was similar to that of our study. Moreover, in our study, EORTC QLQ-ELD14 scores were similar to that of Korean studies, except for the item “family support”. For this item, where participants were asked, “Have you felt able to talk to your family about your illness?”, the result was inferior in elderly Japanese people. The results were 29.20 ± 31.16 in Japanese patients aged ≥ 60 years, 29.90 ± 31.06 in Japanese patients aged ≥ 70 years, 45.9 ± 33.7 in Korean patients aged ≥ 60 years, and 66.2 to 77.8 (based on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] score) in patients aged ≥ 70 years in the study of 10 countries, most of which were in Europe. Based on this trend, social background and cultural difference may be one of the points to investigate in future studies with elderly Japanese people with cancer.

Depending on the EORTC QLQ-C30 reference values, for all cancer patients at all stages and all ages, the global health status/QOL’s mean ± SD was 61.3 ± 24.2; and for all cancer patients aged ≥ 70 years it was 60.6 ± 25.1, so our data may be clinically superior to that of the EORTC QLQ-C30 reference values.

Reliability

Internal consistency—Cronbach α

Internal consistency (Cronbach α) was at a similar level to that of other language versions. The internal consistency of the Japanese version had a Cronbach α ≥ 0.7. However, the Cronbach α value for the item “maintaining purpose” in Japanese patients aged ≥ 60 years and ≥ 70 years was 0.65 and 0.62, respectively. It was similar to the results of the 10 countries study (Cronbach α = 0.68 for individuals aged ≥ 70 years), but lower than that of the Korean population aged ≥ 60 years, where Cronbach α was good (0.79). Next, for the item “worries about others” in the Japanese population aged ≥ 60 years and in those aged ≥ 70 years, Cronbach α was 0.67 and 0.68, respectively. It was similar to that of the Korean study (Goo et al. 2017), where Cronbach α was 0.65 (age ≥ 60 years), but not to the original study of the 10 countries, where Cronbach α was good (0.72) (age ≥ 70 years). “Maintaining purpose” and “worries about others” consisted of only two items, and we evaluated them to demonstrate acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach α).

Reliability-ICC

With regards to ICCs, patients with prostate cancer (clinical stages I–III; 5-year survival rate of 100%; patients were stable during the study period) had an ICC of ≥ 0.70 for the test–retest analysis, which was considered good. ICCs for the scales were 0.80 for the ≥ 60 years old age group, which was better than that of the ≥ 70 years age group at 0.70. In the study of 10 countries (Wheelwright et al. 2013), after 1 week, the ICCs were low for “burden of illness” and “family support” in patients aged ≥ 70 years. We agree that EORTC QLQ-ELD14 may be related to both cancer evaluation and non-clinical events.

Standard error of measurement (SEM)

The SEM was not analyzed in the following studies: ten countries of Europe (Wheelwright et al. 2013), Korea (Goo et al. 2017), Spain (Wrazen et al. 2014), Spain (Arraras et al. 2019), and Chile (Lorca et al. 2021). This study clarified that all the scale/items of the SEM and SDC in the ≥ 70 years age group were larger than those for the ≥ 60 years age group, especially “family support” and “maintaining purpose” on the functional scale/items. Moreover, the SEMs/SDCs of all the scales on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 were less than 1, indicating good quality.

Validity

Construct validity

As we were unable to perform a factor analysis, we carried out a multi-trait scaling analysis, and it proved to be a good construct, except for some scales. For the item “worries about others,” other scale correlations were higher than the item’s scale correlation. Item 7 in the “worries about others” (i.e., “have you worried about the future of people who are important to you?”) correlated more highly with item 8 in the “future worries” subscale (r = 0.63, ≥ 60 years age group, r = 0.62, ≥ 70 years age group). This may be because the word "future" is shared in items 7, 8, and 9. It was similar to the results of the Korean study (Goo et al. 2017).

Criterion validity

We concluded that we had consistent findings for sufficient hypotheses to test for construct validity, as 90% of the results were in accordance with the hypotheses. We found that the hypotheses were based on literature and on theoretical considerations.

Known-group comparisons were demonstrated by the ability to distinguish subgroups of patients with different clinical profiles. This study demonstrated the clinical validity of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 by its ability to distinguish between different comorbidities, and the G8 score, in particular.

The ≥ 60 years age group had superior scores for all scales, except “family support”, compared to the ≥ 70 years age group. In our study hypotheses, similar to that of the Korean study (Goo et al. 2017), clinical stages III and IV patients were assumed to have more worries about others. However, this hypothesis was not supported in this study.

Patients with comorbidities in the ≥ 60 years age group had significantly inferior scores except for “family support”. Patients with comorbidities in the ≥ 70 years old age group had significantly inferior scores except for “family support”, “worries about others”, and “future worries”. Moreover, our results indicated that frailty, identified by G8 scores, was strongly associated with poor EORTC QLQ-ELD14 scale results. Both patient groups with frailty (≥ 60 and ≥ 70 years age groups) had significantly inferior scores except for “family support”. The QLQ-ELD14 identified patient groups defined by comorbidities and G8 scores.

Relationship between the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-ELD14

The divergent validity of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 was assessed by evaluating the correlations between its subscales and that of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Criterion validity was demonstrated by the lack of a strong correlation between the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and the C30, except for “mobility” (ELD14) and “physical functioning” (C30); this was similar to the results of other studies (Michelson et al. 2000; Wrazen et al. 2014; Goo et al. 2017; Arraras et al. 2019). The hypotheses were based on the literature and theoretical considerations. We assumed a moderate to strong correlation between “mobility” and “physical functioning”; between future anxiety, “future worries” and “emotional functioning”; and between “burden of illness” and “social functioning”. This was similar to other studies (Michelson et al. 2000; Wrazen et al. 2014; Goo et al. 2017; Arraras et al. 2019). Our current Japanese study had a stronger correlation (r = − 0.797 and − 0.799 for the ≥ 60 and ≥ 70 years age groups, respectively) between “mobility” (ELD14) and “physical functioning” (C30); this was similar to the Korean study; r = − 0.72 for the ≥ 60 years age group. “Family support”, “global health status/QOL”, and the functioning scales/items of the EORTC QLQ-C30 did not have a positive correlation, and these trends were similar to those of a previous Korean study (Goo et al. 2017). This may be attributed to differences in how the questions were perceived.

The results of criterion validity with the EORTC QLC-C30 indicate that HRQOL issues assessed by the QLQ-ELD14 are different from those assessed by the commonly used QLQ-C30. Our results indicated that the Japanese version of the QLQ-ELD14 is a useful tool for assessing the HRQOL of elderly Japanese people with cancer.

Responsiveness: responsiveness to change analysis (RCA)

We demonstrated consistent findings on sufficient hypothesis testing for responsiveness, as 80% of the results were in accordance with the hypotheses. To determine the sensitivity to change, the paired-t test, ES, and SRM were performed. We analyzed the RCA (n = 1302; ≥ 60 years age group, n = 888; ≥ 70 years age group) one year later.

Our hypothesis was that the items of “maintaining purpose” and “future worries” of the EORTC QLQ ELD-14 would have worsened after the commencement of the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with the results prior to the pandemic. In our Japanese study, patients had significantly decreased scores (SRM, 0.21 for the ≥ 60 years age group and 0.26 for the ≥ 70 years age group) for the “maintaining purpose” item after the commencement of the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with before. Contrastingly, although items such as “burden of illness” and “joint stiffness” showed a significant difference in the scores, we found no clinical difference because the SRM was very low. However, the t change mean score was very low (SRM < 0.2), except for the item “maintaining purpose”. As mentioned earlier, the concept of HRQOL in elderly patients is not linked to any specific medical condition and is a broad concept (Wilson and Cleary 1995). In our study, “maintaining purpose” on the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 and the “global health status/QOL” and “summary score” on the EORTC QLQ C30 had very low correlations to score changes. It seems to be due to different conceptualizations of “maintaining purpose”. In the original study in the 10 countries, the item “maintaining purpose” is complex and covers two concepts: positive outlook and motivation for activities (Wheelwright et al. 2013). Another prospective study using the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 in radiotherapy patients ≥ 80 years, six months after radiotherapy, a significant and clinically relevant deterioration of HRQOL was seen in the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 for “future worries”, “burden of illness”, and “family support”. For the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 questionnaire, older head and neck cancer patients, up to 1 year after curative treatment, reported greater difficulty in “maintaining purpose” 12 months after treatment. Including these points, further studies are needed to evaluate the responsiveness of this scale for elderly Japanese patients with cancer under various circumstances.

In previous studies regarding responsiveness, the study in 10 countries (Wheelwright et al. 2013) found no change in the score of the progress stage group three months later, in the ≥ 70 years age group. The studies in Korea (Goo et al. 2017), Spain (Wrazen et al. 2014), Spain (Arraras et al. 2019), and Chile (Lorca et al. 2021) did not analyze responsiveness data. When assessing responsiveness, one of the most difficult tasks is formulating challenging hypotheses (Mokkink et al., 2018a, b). When we planned the hypotheses of this study, there was no available data on evaluating HRQOL change in people with cancer, especially the elderly. Subsequently, we found two recent studies (Jeppesen et al. 2021; Koinig et al. 2021) that compared pre-COVID-19 pandemic and intra-pandemic scores and revealed that the “global health status/QOL” of the EORTC QLQ-C30 did not change significantly with the pandemic, and is considered clinically important. The survey (Jeppesen et al. 2021) was published in Denmark in May 2020, with 4571 respondents (mean 66 years, 40% male, 30% breast cancer, 22% intractable cancer). The average “global health status/QOL” score was 71.3 points, which is the same as that of our present study. There was no clinically significant difference in the HRQOL score compared to that before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Another study (Koinig et al. 2021) found that the COVID-19 pandemic only had a slight impact on the “global health status/QOL” (mean global health status/QOL score, Δ = − 1.95); this was similar to our study findings (Δ = − 1.85 for the ≥ 60 years age group and − 2.09 for the ≥ 70 years age group), where all the values were below the threshold for clinically meaningful differences. Therefore, we suggest that our hypotheses might not have been adequate to evaluate the responsiveness of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14.

Our study had certain limitations. Our study participants came from a single hospital with better HRQOL. The G8 frailty score was self-assessed by the elderly participants. We could not use factor analysis to evaluate construct validity or the maximal information coefficient (MIC) to analyze measurement error or to evaluate MIC. Moreover, we were unable to analyze cross-cultural validity by COSMIN methods. Responsiveness was difficult to assess, and so was creating a hypothesis for the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic without reference data. The original version stated that non-clinical factors could affect older patients more than younger ones. Future studies will need to explore this hypothesis in Japan. We propose that HRQOL in older individuals is a wide concept. Japan has the world’s most rapidly aging population. Therefore, the contribution of large datasets to create evidence to aid elderly patients with cancer is necessary.

The strength of our study lies in the fact that this scale seems to be usable even for elderly individuals with cancer aged over 60 and 70 years in the Japanese population. The EORTC QLQ-ELD14 can evaluate generic issues affecting older adults with cancer not covered by the EORTC QLQ-C30 or site-specific modules. Moreover, the low number of questions per scale in the EORTC QLQ- ELD14 helps reduce the burden on older adults. Nonetheless, we collected extensive data despite the adverse circumstances, and for the first time, we could demonstrate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on HRQOL using the EORTC QLQ-ELD14, with the cooperation of elderly patients with cancer. In the future, using the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 to evaluate comparisons in many research areas and clinical settings may provide clinically useful conclusions on various relevant topics.

Conclusion

Our findings show that the Japanese version of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 is an acceptable tool that can be used for cancer research and clinical management to assess the HRQOL of elderly Japanese patients with cancer. Moreover, this scale can also be used for individuals aged over 60 and 70 years. Further, the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 showed worsening of the “maintaining purpose” parameter after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with before. Elderly people with cancer tend to prefer a better HRQOL over an increased span of life.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:365–376. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365

Arraras JI, Asin G, Illarramendi JJ, Manterola A, Salgado E, Dominguez MA (2019) The EORTC QLQ-ELD14 questionnaire for elderly cancer patients. Validation study for elderly Spanish breast cancer patients. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 54:321–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2019.05.001

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Katz JN, Wright JG (2001) A taxonomy for responsiveness. J Clin Epidemiol 54:1204–1217. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00407-3

Bellera CA, Rainfray M, Mathoulin-Pélissier S, Mertens C, Delva F, Fonck M, Soubeyran PL (2012) Screening older cancer patients: first evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann Oncol 23:2166–2172. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdr587

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16:297–334

Fayers PM, Machin D (2000) Quality of life: assessment analysis and interpretation. Wiley, Chichester

Fayers PM, Machin D (2013) Quality of life: the assessment, analysis and interpretation of patient-reported outcomes. Wiley, Chichester

Fitzsimmons D, Gilbert J, Howse F, Young T, Arrarras JI, Brédart A, Hawker S, George S, Aapro M, Johnson CD (2009) A systematic review of the use and validation of health-related quality of life instruments in older cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 45:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.036

Goo AJ, Shin DW, Yang HK, Park JH, Kim SY, Shin JY, Kim YA, Kim C, Hong NS, Min YJ, Park KJ (2017) Cross-cultural application of the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 questionnaire for elderly patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 8:271–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2017.03.001

Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Bjordal K, Kaasa S (1998) Using reference data on quality of life—the importance of adjusting for age and gender, exemplified by the EORTC QLQ-C30 (+3). Eur J Cancer 34:1381–1389. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00136-1

Jeppesen SS, Bentsen KK, Jørgensen TL, Holm HS, Holst-Christensen L, Tarpgaard LS, Dahlrot RH, Eckhoff L (2021) Quality of life in patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic—a Danish cross-sectional study (COPICADS). Acta Oncol 60:4–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2020.1830169

Johnson C, Fitzsimmons D, Gilbert J, Arrarras JI, Hammerlid E, Bredart A, Ozmen M, Dilektasli E, Coolbrandt A, Kenis C, Young T, Chow E, Venkitaraman R, Howse F, George S, O’Connor S, Yadegarfar G, EORTC Quality of Life Group (2010) Development of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire module for older people with cancer: the EORTC QLQ-ELD15. Eur J Cancer 46:2242–2252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2010.04.014

Kasper B (2020) The EORTC. QLQ-C30 Summary Score as a prognostic factor for survival of patients with cancer: a commentary. Oncologist 25:e610–e611. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0749

Kobayashi K, Takeda F, Teramukai S, Gotoh I, Sakai H, Yoneda S, Noguchi Y, Ogasawara H, Yoshida K (1998) A cross-validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) for Japanese with lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 34:810–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00395-X

Koinig KA, Arnold C, Lehmann J, Giesinger J, Köck S, Willenbacher W, Weger R, Holzner B, Ganswindt U, Wolf D, Stauder R (2021) The cancer patient’s perspective of COVID-19-induced distress-a cross-sectional study and a longitudinal comparison of HRQOL assessed before and during the pandemic. Cancer Med 10:3928–3937. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.3950

Lorca LA, Sacomori C, Fasce Pineda G, Vidal Labra R, Cavieres Faundes N, Plasser Troncoso J, Leao Ribeiro I (2021) Validation of the EORTC QLQ-ELD 14 questionnaire to assess the health-related quality of life of older cancer survivors in Chile. J Geriatr Oncol 12:844–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.12.014

Michelson H, Bolund C, Nilsson B, Brandberg Y (2000) Health-related quality of life measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30—reference values from a large sample of Swedish population. Acta Oncol 39:477–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/028418600750013384

Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, Schonberg MA, Boyd CM, Burhenn PS, Canin B, Cohen HJ, Holmes HM, Hopkins JO, Janelsins MC, Khorana AA, Klepin HD, Lichtman SM, Mustian KM, Tew WP, Hurria A (2018) Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO guideline for geriatric oncology. J Clin Oncol 36:2326–2347. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8687

Mokkink LB, de Vet HCW, Prinsen CAC, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Bouter LM, Terwee CB (2018a) COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual Life Res 27:1171–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1765-4

Mokkink LB, Prinsen CAC, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW, Terwee CB (2018b) COSMIN methodology for systematic reviews of Patient‐Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) user manual, version 1.0 (2018b). https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-syst-review-for-PROMs-manual_version-1_feb-2018b.pdf. Accessed 14 May 2022

Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J (1998) Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16:139–144. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139

Pilleron S, Sarfati D, Janssen-Heijnen M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F, Soerjomataram I (2019) Global cancer incidence in older adults, 2012 and 2035: a population-based study. Int J Cancer 144:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31664

Schwarz R, Hinz A (2001) Reference data for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30 in the general German population. Eur J Cancer 37:1345–1351. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00447-0

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL (1979) Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 86:420–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420

Tester S, Hubbard G, Downs M, McDonald C, Murphy J (2004) Growing older: quality of life in old age. In: Hennessy CH, Walker C, Walker A (eds) Frailty and institutional life. Open University Press, Maidenhead, pp 209–225

Wheelwright S, Darlington AS, Fitzsimmons D, Fayers P, Arraras JI, Bonnetain F, Brain E, Bredart A, Chie WC, Giesinger J, Hammerlid E, O’Connor SJ, Oerlemans S, Pallis A, Reed M, Singhal N, Vassiliou V, Young T, Johnson C (2013) International validation of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 questionnaire for assessment of health-related quality of life elderly patients with cancer. Br J Cancer 109(4):852–858. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.407

Wilson IB, Cleary PD (1995) Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 273:59–65. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03520250075037

World Health Organization (2021). Aging Health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health Accessed 12 May 2022

Wrazen W, Golec EB, Tomaszewska IM, Walocha E, Dudkiewicz Z, Tomaszewski KA (2014) Preliminary psychometric validation of the Polish version of the EORTC elderly module (QLQ-ELD14). Folia Med Cracov 54(2):35–45

Wright P, Smith A, Booth L, Winterbottom A, Kiely M, Velikova G, Selby P (2005) Psychosocial difficulties, deprivation and cancer: three questionnaire studies involving 609 cancer patients. Br J Cancer 93(6):622–626. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602777

Young T, De Haes H, Curran D et al (1999) EORTC guidelines for assessing quality of life in clinical trials. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group Publication, Brussels, pp 2–930064

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the patients that participated in the study. We would like to also thank the EORTC Translation Team. This work was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (18K10312 and 19K22764), the Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research, and the SGH Foundation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (18K10312 and 19K22764), the Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research, and the SGH Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation was performed by YK, RI, HF, KA, SN, SA, TT, MK, JI, and KO, and KT. Data collection was performed by YK, RI, and MK. Analyses were performed by YK, JK, and the Editage Team. The first draft of the manuscript was written by YK and all the authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Consent to participate

Prior to the study, participants were asked to sign a written informed consent form to confirm their willingness to participate in this study.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyushu University (2019-450).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kinoshita, Y., Izukura, R., Kishimoto, J. et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Japanese version of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 in evaluating the health-related quality of life of elderly patients with cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 149, 4899–4914 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-022-04414-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-022-04414-2