Abstract

Children have the right to grow up free from the hazards associated with tobacco smoking. Tobacco smoke exposure can have detrimental effects on children’s health and development, from before birth and beyond. As a result of effective tobacco control policies, European smoking rates are steadily decreasing among adults, as is the proportion of adolescents taking up smoking. Substantial variation however exists between countries, both in terms of smoking rates and regarding implementation, comprehensiveness and enforcement of policies to address smoking and second-hand smoke exposure. This is important because comprehensive tobacco control policies such as smoke-free legislation and tobacco taxation have extensively been shown to carry clear health benefits for both adults and children. Additional policies such as increasing the legal age to buy tobacco, reducing the number of outlets selling tobacco, banning tobacco display and advertising at the point-of-sale, and introducing plain packaging for tobacco products can help reduce smoking initiation by youth. At societal level, health professionals can play an important role in advocating for stronger policy measures, whereas they also clearly have a duty to address smoking and tobacco smoke exposure at the patient level. This includes providing cessation advise and referring to effective cessation services.

Conclusion: Framing of tobacco exposure as a child right’s issue and of comprehensive tobacco control as a tool to work towards the ultimate goal of reaching a tobacco-free generation can help accelerate European progress to curb the tobacco epidemic.

What is Known: • Tobacco exposure is associated with a range of adverse health effects among babies and children. • Comprehensive tobacco control policies helped bring down smoking rates in Europe and benefit child health. | |

What is New: • Protecting the rights and health of children provides a strong starting point for tobacco control advocacy. • The tobacco-free generation concept helps policy-makers set clear goals for protecting future generations from tobacco-associated harms. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Synopsis

Tobacco smoke exposure poses a range of significant risks to child health and violates child rights [1, 2]. While the health impacts of smoking for children generally receive less attention than those for adults, they constitute a substantial cause of mortality and morbidity in early life. Levels of tobacco exposure have come down in recent years in Europe, driven by robust policy action at local, national and regional levels. However, the serious related harms still evident mean that we have further to go to achieve a truly tobacco-free generation. Required actions including expanding smoke-free legislation, increases in tax and price and more consistently delivering interventions within health care settings are all warranted.

How tobacco affects children

There are a number of pathways through which children are affected by tobacco smoking. Before birth exposure can occur through either active smoking or second-hand smoke (SHS) exposure of pregnant women, while growing up children can be exposed to SHS for example by smoking within the family, and in later childhood they may take up smoking themselves. Each of these pathways harms children in different ways. In Europe, SHS exposure is linked to 170 thousand deaths every year, including 2300 deaths among children 0–14 years [3]. Smoking during pregnancy can cause serious sequelae including birth defects, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction and perinatal mortality [4, 5]. Tobacco exposure during early life furthermore increases children’s risks of sudden infant death syndrome [6], of developing respiratory tract infections (RTIs) [7], these generally being more severe, and of asthma exacerbations [8]. Emerging evidence suggests that smoking may even have impacts across generations, with for example increased risk of asthma among grandchildren of women who smoked in pregnancy [9, 10]. Exposure of mothers to SHS in pregnancy is also associated with increased risks of many of these outcomes, albeit to a lesser degree [11].

The last main pathway of children taking up smoking themselves leaves them vulnerable to the myriad health problems caused by smoking among adults [12]. Children who try tobacco at an earlier age are more likely to go on to become smoking adults [12]. Also, children living with a smoker are much more likely to try tobacco (OR 1.7 if father smokes, 2.2 if mother smokes, and 2.7 if both parents smoke), which highlights the exemplar role of parents in not smoking themselves [13]. There is additionally some evidence that third-hand smoke (THS), that is, residual smoke pollutants lingering on environmental surfaces after the smoke has cleared, may be harmful for health [14]. Studies have demonstrated increased levels of nicotine derivatives in non-smokers living in homes originally occupied by smokers [15]. THS constituents have even been found in premature babies cared for in an intensive care environment whose parents smoke, this being associated with local environmental THS contamination [16]. A wide variety of adverse health effects from THS have been observed in animal experiments [14], and the finding that children whose parents only smoke outside are still at increased risk of developing respiratory symptoms indicates that THS can also adversely impact human health [17, 18]. The different pathways through which we know that tobacco can harm children mean that we need action on reducing tobacco smoke exposure, ideally through reducing the number of adult smokers, as well as efforts to prevent taking up smoking among children themselves.

Tobacco use in Europe: facts and figures

Europe is one of the world’s regions with the highest prevalence of smoking, especially among women [19]. Fortunately, the prevalence of smoking has been declining in Europe (Fig. 1) [20]. In 2020, the prevalence of smoking among people aged 15 years or older was 23% in the European Union (EU) [21], down from 29% a decade earlier [22]. However, the EU is very heterogeneous with regard to tobacco use. In countries such as Greece, Bulgaria and Croatia, more than 35% of those aged 15 years or older are current smokers, whereas the prevalence of smoking is as low as 7% in Sweden and 12% in the UK [21]. The most recent Eurobarometer survey on tobacco in 28 European countries found that 26% of men and 21% of women were current smokers in 2020 [21]. Despite the high prevalence of smoking among women in Europe, it appears that many successfully quit smoking during pregnancy without external help; however, data on this are scarce and based on selected populations that may not be nationally representative [23, 24]. Women in vulnerable groups, with low education and unplanned pregnancies, have been consistently shown to be less likely to quit smoking during pregnancy across several European countries [23, 24]. This is consistent with studies in which people facing financial problems are more likely to smoke and be exposed to SHS, which further compounds inequalities in active and passive exposure to tobacco smoke among pregnant women and young children in Europe [21]. Existing socioeconomic disparities in smoking contribute importantly to health inequalities in early life [25]. Among pregnant women, those requiring external help to quit smoking have relatively low success rates, and many restart smoking after pregnancy [26].

It has been estimated that 20% of pregnant women and 12% of children are regularly exposed to SHS at home in the EU [27], but this also varies widely between countries depending on the prevalence of smoking and the level of enforcement of smoke-free legislation. This is reflected in recent European data on exposure to SHS in restaurants. While in most central and northern European countries fewer than 5% of the respondents reported recent SHS exposure in a restaurant in 2020, there are countries like Cyprus where 40% of people who recently visited a restaurant reported being exposed to SHS [21]. Given the lingering presence of THS in environments where people smoke or where smokers are [14,15,16], the proportion of women and children exposed to THS is likely even higher. The picture is further complicated by the recent rise in popularity of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products. Although current use of these products is not widespread, they are quite popular in certain countries and among younger ages, including women of childbearing age [21]. Studies in Germany and the UK have shown that some women may continue to use e-cigarettes during pregnancy or start using them to quit smoking [28, 29]. The clinical implications of this are now only starting to be explored [30].

Regarding smoking uptake, a European survey in 2017/2018 showed that, at age 11, 5% of boys and 2% of girls had ever smoked, this increasing to 29% and 27%, respectively, at age 15 [31]. Rates had improved slightly compared to 2014, but there were substantial between-country differences, with Bulgaria, Lithuania and Italy having particularly high adolescent smoking rates [31]. A recent European survey confirmed that well over half of adult smokers started smoking regularly before age 18 [32]. Also, adolescents who use e-cigarettes are more likely to become smokers in the future, although it is not entirely clear if this indicates a true gateway effect or shared risk factors [33]. Even those who do not transition to combustible tobacco use may still be exposed to health risks associated with e-cigarette use [34]. Considering the above as well as the increasing popularity of heated tobacco products among youth [21], these novel products highlight the need to expand tobacco control policies and protect children from risks associated with their use.

Tobacco control progress in Europe

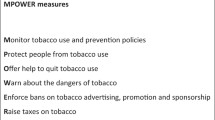

Recent declines in smoking in Europe can be largely attributed to the aggressive tobacco control policies implemented across the continent [20]. Almost all European countries have ratified the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), an international public health treaty launched in 2003 which outlines key evidence-based policies to curb the tobacco epidemic [35]. Close to 450 million people are also covered by the EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) which mandates additional tobacco control measures, such as pictorial warning labels [36]. According to the WHO, the majority of countries in the European region score highly in monitoring tobacco use, banning tobacco advertising, implementing health warnings regarding the dangers of tobacco use, taxing tobacco products and supporting smoking cessation [19], making Europe the region with the best adherence to the WHO MPOWER recommendations (Table 1; Fig. 2). Although only few countries have implemented all these policies to the highest level as recommended by the WHO, including comprehensive smoke-free legislation in public places, sustained increases in tobacco taxation, free support for smoking cessation and large pictorial warning labels [19], some have adopted additional tobacco control policies, such as smoking bans in vehicles when children are present and plain packaging. Overall, implementation is lacking in several countries, especially in areas such as smoke-free environments. Fourteen out of 36 European countries received a score below 50 (out of 100) in the most recent Tobacco Control Scale (TCS), which ranks countries based on a number of tobacco control indicators [37]. The TCS recognises the UK, France and Ireland as tobacco control leaders within Europe, with Germany, Switzerland and Luxembourg performing most poorly.

Percentage of European countries covered in 2008 and 2018 by each of the MPOWER policies at the highest level as recommended by the World Health Organization. M monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies, P protect people from tobacco smoke (i.e. smoke-free legislation), O offer help to quit tobacco use (i.e. access to and reimbursement of cessation services), W warn about the dangers of tobacco (e.g. pack warnings (W1); media campaigns (W2)), E enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship, R raise taxes on tobacco

Impact of tobacco control policies on children

These measures to reduce smoking among the general population can benefit children by reducing the exposure of children to SHS as well as denormalising the act of smoking. For example, smoke-free laws in public places are one of the most well-evaluated tobacco control interventions in both Europe and other high-income countries. Systematic review evidence points to reductions in preterm births, and in hospital attendance for severe RTIs and asthma hospitalisations among children from these measures [38]. These interventions can work to reduce SHS exposure in public places covered by these laws, through potential reductions in smoking prevalence in their own right, and through norm-spreading behavioural changes such as reducing smoking in the home. These impacts can be enhanced by strong mass media messaging and advertising: recent data from Scotland indicates that a novel campaign called Take It Right Outside, focused on reducing domestic SHS exposure, was successful in reducing asthma admissions among children under 5 years old [39].

Increases in prices of tobacco are also linked to improved infant survival in Europe [40], most likely through reductions in maternal smoking and SHS exposure. One study in 23 EU countries estimated that cigarette price increases between 2005 and 2014 had averted a total of over 9000 infant deaths [40]. Several countries are now moving forward by implementing novel policies including the banning of smoking inside private vehicles with children present [41]. As children do not have substantial control over their environment, and as smoking inside vehicles is linked to very high levels of toxins, these measures are justified to reduce exposure and harm. Emerging evidence now indicates that these laws can help reduce exposure to SHS among children in vehicles [42]. Nonetheless, one study pointed to low levels of enforcement of these laws jeopardising the potential health gains [43], an issue which is common across all tobacco control policies.

There are also policies with the potential to reduce the initiation of smoking among children themselves. This is crucial given that about one in two children who tries tobacco will go on to develop nicotine addiction and that over half of adult smokers commenced smoking when they were still a child [32, 44]. Effective policies include restricting the numbers of outlets selling tobacco [45], restricting the display of tobacco at point-of-sale [46, 47] and age of sale regulations [48]. Finally the introduction of plain (or standardised) packaging for tobacco has been successful in restricting the ability of the tobacco industry to use packs for advertising to lure children into using tobacco [49]. Given that early initiation of smoking is often influenced by parents and peers, an overarching impact of tobacco control efforts bringing down overall smoking rates and changing social norms is important [32].

Addressing smoking in the health care setting

Effective tobacco control policies can make a substantial contribution to benefiting child health at the population level, as outlined [1, 50]. At the individual level, perinatal and paediatric health care providers can play a crucial role in addressing smoking as a key determinant of adverse pregnancy and child health outcomes. Enquiring about smoking status of future parents, caregivers and teenage patients should be an integral part of care. Opening subsequent discussions about the dangers of smoking and the benefits of cessation is essential. A non-judgmental, affirmative approach is important, framing the issue as a cause for concern from the child’s point of view. Professionals should realise that nicotine is highly addictive and that many additional factors may contribute to sustaining smoking, providing barriers to effective cessation even though many smokers would rather quit. Smokers should always be provided with at least a brief smoking advice and health professionals need to be conscious of national and local routes to direct them towards effective cessation support services [51, 52]. These may include national quit lines, counselling services and pharmacological support including nicotine replacement therapy. Health professionals should furthermore consider their exemplary role towards patients and the wider society in refraining from smoking themselves [53, 54].

Tobacco as a child rights issue in Europe

Human rights and the rights of the child, in particular, are a potent tool for achieving a smoke-free generation in Europe [2, 55]. Given their vulnerability, children have, among others, the right to special protection against physical and moral dangers, such as those implied by tobacco, and the right to health, which must be guaranteed even in the private sphere. After all, the best interests of the child, a focal human rights principle, should be considered in all actions pertaining to children. The mobilisation of both the international and the European human rights law monitoring machinery can offer a significant advantage in the fight against smoking (Table 2) [56, 57]. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [58], ratified by all European States and also explicitly recalled in the Preamble of the FCTC [35], has been interpreted to imply that States have a legal obligation to protect children against the harmful effects of tobacco [2]. The same goes for the Council of Europe European Social Charter [59]. The European Committee of Social Rights, which monitors its implementation, regards smoking as one of the dangers against which children and young people should be protected and requires health education on prevention of smoking throughout the entire period of schooling as part of school curricula [60, 61]. The Committee points out that, to be effective, any prevention policy on tobacco must restrict the supply of tobacco through controls on production, distribution, advertising and pricing. In particular, the sale of tobacco to young persons must be banned [62], as must smoking in public places, including transport, and advertising on posters and in the press [63]. Clearly, these conclusions are largely consistent with WHO FCTC and TPD provisions outlined earlier [35, 36].

These observations show the potentials of framing tobacco as a child rights issue in Europe. The deployment of human rights–based arguments and human rights language, with emphasis on the rights of the child and its best interests, can be significant in awareness raising, policy-making and litigation to guarantee a tobacco-free generation. These potentials can be further untapped especially within the Council of Europe human rights system [64], through the promotion of the existing standards and the integration of tobacco control in the work of all the Council of Europe’s relevant organs. The more systematic invocation of these standards by individuals (e.g. children, parents) and entities (e.g. advocacy groups, state authorities) implicated in the fight against tobacco to protect children’s health can be an additional path towards this direction. The European Convention on Human Rights and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights can also be further used in this context [65,66,67,68].

European initiatives for a tobacco-free generation

The framing of tobacco use as a child rights issue and emphasising the need to protect children from the harms of tobacco are clearly gaining momentum as a starting point for advocacy for stronger tobacco control policies [69]. An increasing number of countries have set specific targets for working towards attaining a smoke-free (or tobacco-free) generation by a fixed target date, framing their tobacco control strategy around this concept. Variation exists in such goalsetting, whether aiming for overall smoking rates to go below a certain level or for smoking initiation among youth to drop to zero, or whether going for smoke-free, tobacco-free (i.e. including non-combustible tobacco) or nicotine-free (i.e. including e-cigarettes). England for example in their tobacco control plan for 2017–2022 expressed the ambition to reduce regular smoking among 15-year-olds from 8 to ≤ 3% and reduce smoking during pregnancy from 10.7 to ≤ 6% [70]. In the Netherlands, the smoke-free generation concept was a key driver of goalsetting within the National Prevention Agreement signed by the national government and over 70 societal organisations in 2019 [71]. In addition to governmental policies, the Agreement specifies targets and responsibilities for signatories including for example ensuring that the grounds of petting zoos, sports associations and health care institutions will become smoke-free. Extension of smoke-free policies to include outdoor areas and private areas such as cars, implementing of plain packaging and restricting the point-of-sale display of tobacco products, and reducing the number of outlets selling tobacco are among the key policies included in many national tobacco-free generation strategies, with the overall aim to denormalise smoking [1, 44, 70, 71].

Conclusion

Children have the right to grow up free from the substantial hazards associated with tobacco use and they need to be acknowledged as important stakeholders in its regulation. Strong tobacco control policies are associated with clear population health benefits, including among children. Although European smoking rates are relatively high, particularly among women, they are decreasing steadily under influence of effective policy-making. Substantial between-country variation however exists and much more can and still needs to be done to work towards reaching the ultimate goal of attaining a tobacco-free generation.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- FCTC:

-

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- EU:

-

European Union

- RTI:

-

Respiratory tract infection

- SHS:

-

Second-hand smoke

- TCS:

-

Tobacco control scale

- THS:

-

Third-hand smoke

- TPD:

-

Tobacco Products Directive

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization (2021) Tobacco control to improve child health and development: thematic brief. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/340162. Accessed 16 April 2021

Toebes B, Gispen ME, Been JV, Sheikh A (2018) A missing voice: the human rights of children to a tobacco-free environment. Tob Control 27:3–5

Global Health Data Exchange (2019) GBD Results Tool. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool. Accessed 16 April 2021

Philips EM, Santos S, Trasande L, Aurrekoetxea JJ, Barros H, von Berg A, Bergström A, Bird PK, Brescianini S, Ní Chaoimh C, Charles MA, Chatzi L, Chevrier C, Chrousos GP, Costet N, Criswell R, Crozier S, Eggesbø M, Fantini MP, Farchi S, Forastiere F, van Gelder MMHJ, Georgiu V, Godfrey KM, Gori D, Hanke W, Heude B, Hryhorczuk D, Iñiguez C, Inskip H, Karvonen AM, Kenny LC, Kull I, Lawlor DA, Lehmann I, Magnus P, Manios Y, Melén E, Mommers M, Morgen CS, Moschonis G, Murray D, Nohr EA, Nybo Andersen AM, Oken E, Oostvogels AJJM, Papadopoulou E, Pekkanen J, Pizzi C, Polanska K, Porta D, Richiardi L, Rifas-Shiman SL, Roeleveld N, Rusconi F, Santos AC, Sørensen TIA, Standl M, Stoltenberg C, Sunyer J, Thiering E, Thijs C, Torrent M, Vrijkotte TGM, Wright J, Zvinchuk O, Gaillard R, Jaddoe VWV (2020) Changes in parental smoking during pregnancy and risks of adverse birth outcomes and childhood overweight in Europe and North America: an individual participant data meta-analysis of 229,000 singleton births. PLoS Med 17:e1003182

Faber T, Been JV, Reiss IK, Mackenbach JP, Sheikh A (2016) Smoke-free legislation and child health. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 26:16067

Zhang K, Wang X (2013) Maternal smoking and increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome: a meta-analysis. Leg Med (Tokyo) 14:115–121

Jones LL, Hashim A, McKeever T, Cook DG, Britton J, Leonardi-Bee J (2011) Parental and household smoking and the increased risk of bronchitis, bronchiolitis and other lower respiratory infections in infancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res 12:5

He Z, Wu H, Zhang S, Lin Y, Li R, Xie L, Li Z, Sun W, Huang X, Zhang CJP, Ming WK (2020) The association between secondhand smoke and childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol 55:2518–2531

Lodge CJ, Bråbäck L, Lowe AJ, Dharmage SC, Olsson D, Forsberg B (2018) Grandmaternal smoking increases asthma risk in grandchildren: a nationwide Swedish cohort. Clin Exp Allergy 48:167–174

Mahon GM, Koppelman GH, Vonk JM (2021) Grandmaternal smoking, asthma and lung function in the offspring: the Lifelines cohort study. Thorax 76:441–447

Leonardi-Bee J, Britton J, Venn A (2011) Secondhand smoke and adverse fetal outcomes in nonsmoking pregnant women: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 127:734–741

Laverty AA, Filippidis FT, Taylor-Robinson D, Millett C, Bush A, Hopkinson NS (2019) Smoking uptake in UK children: analysis of the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Thorax 74:607–610

Leonardi-Bee J, Jere ML, Britton J (2011) Exposure to parental and sibling smoking and the risk of smoking uptake in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 66:847–855

Díez-Izquierdo A, Cassanello-Peñarroya P, Lidón-Moyano C, Matilla-Santander N, Balaguer A, Martínez-Sánchez JM (2018) Update on thirdhand smoke: a comprehensive systematic review. Environ Res 167:341–371

Matt GE, Quintana PJ, Zakarian JM, Fortmann AL, Chatfield DA, Hoh E, Uribe AM, Hovell MF (2011) When smokers move out and non-smokers move in: residential thirdhand smoke pollution and exposure. Tob Control 20:e1

Northrup TF, Khan AM, Jacob P 3rd, Benowitz NL, Hoh E, Novell MF, Matt GE, Stotts AL (2016) Thirdhand smoke contamination in hospital settings: assessing exposure risk for vulnerable paediatric patients. Tob Control 25:619–623

Ogbu SE, Ogbu SC, Khadka D, Kirby RS (2021) Childhood asthma and smoking: moderating effect of preterm birth and birth weight. Cureus 13:e14536

Yamakawa M, Yorifuji T, Kato T, Tsuda T, Doi H (2017) Maternal smoking location at home and hospitalization for respiratory tract infections in Japan. Arch Environ Occup Health 72:343–350

World Health Organization (2019) WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 2019: offer help to quit tobacco use. https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/tobacco-control/who-report-on-the-global-tobacco-epidemic-2019. Accessed 16 April 2021

Feliu A, Filippidis FT, Joossens L, Fong GT, Vardavas CI, Baena A, Castellano Y, Martínez C, Fernández E (2019) Impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and quit ratios in 27 European Union countries from 2006 to 2014. Tob Control 28:101–109

European Commission (2020) Special Eurobarometer Report 506. Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c070c04c-6788-11eb-aeb5-01aa75ed71a1/language-en. Accessed 16 April 2021

European Commission (2010) Special Eurobarometer Report 332. Tobacco. https://data.europa.eu/euodp/nl/data/dataset/S790_72_3_EBS332. Accessed 16 April 2021

Jawad A, Patel D, Brima N, Stephenson J (2019) Alcohol, smoking, folic acid and multivitamin use among women attending maternity care in London: a cross-sectional study. Sex Reprod Healthc 22:100461

Smedberg J, Lupattelli A, Mårdby A-C, Nordeng H (2014) Characteristics of women who continue smoking during pregnancy: a cross-sectional study of pregnant women and new mothers in 15 European countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14:213

Gray R, Bonellie SR, Chalmers J, Greer I, Jarvis S, Kurinczuk JJ, Williams C (2009) Contribution of smoking during pregnancy to inequalities in stillbirth and infant death in Scotland 1994-2003: retrospective population based study using hospital maternity records. BMJ 339:b3754

Jones M, Lewis S, Parrott S, Wormall S, Coleman T (2016) Re-starting smoking in the postpartum period after receiving a smoking cessation intervention: a systematic review. Addiction 111:981–990

Carreras G, Lachi A, Cortini B, Gallus S, López MJ, López-Nicolás Á, Lugo A et al (2020) Burden of disease from exposure to secondhand smoke in children in Europe. Pediatr Res. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01223-6

Schilling L, Spallek J, Maul H, Schneider S (2021) Study on E-Cigarettes and Pregnancy (STEP) - results of a mixed methods study on risk perception of e-cigarette use during pregnancy. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 81:214–223

Bowker K, Lewis S, Phillips L, Orton S, Ussher M, Naughton F, Bauld L, Coleman T, Sinclair L, McRobbie H, Khan A, Cooper S (2021) Pregnant women’s use of e-cigarettes in the UK: a cross-sectional survey. BJOG 128:984–993

Froggatt S, Reissland N, Covey J (2020) The effects of prenatal cigarette and e-cigarette exposure on infant neurobehaviour: a comparison to a control group. EClinicalMedicine 28:100602

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (2020) Spotlight on adolescent health and well-being. Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey in Europe and Canada. International report. Volume 1. Key findings. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/332091/9789289055000-eng.pdf. Accessed 16 April 2021

Filippidis FT, Agaku IT, Vardavas CI (2015) The association between peer, parental influence and tobacco product features and earlier age of onset of regular smoking among adults in 27 European countries. Eur J Public Health 25:814–818

Chan GC, Stjepanovič D, Lim C, Sun T, Anandan AS, Connor JP, Gartner C, Hall WD, Lueng J (2020) Gateway or common liability? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of adolescent e-cigarette use and future smoking initiation. Addiction 116:743–756

US Department of Health and Human Services (2016) E-cigarette use among youth and young adults. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/e-cigarettes/index.htm. Accessed 7 May 2021

World Health Organization (2018) WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. https://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en. Accessed 16 April 2021

European Parliament, Council of the European Union (2014) Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC. Official Journal of the European Union 127:1–38

Feliu A, Fernández E, Baena A, Joossens L, Peruga A, Fu M, Martínez C (2020) The Tobacco Control Scale as a research tool to measure country-level tobacco control policy implementation. Tob Induc Dis 18:91

Faber T, Kumar A, Mackenbach JP, Millett C, Basu S, Sheikh A, Been JV (2017) Effect of tobacco control policies on perinatal and child health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2:e420–e437

Turner S, Mackay D, Dick S, Semple S, Pell JP (2020) Associations between a smoke-free homes intervention and childhood admissions to hospital in Scotland: an interrupted time-series analysis of whole-population data. Lancet Public Health 5:e493–e500

Filippidis FT, Laverty AA, Hone T, Been JV, Millett C (2017) Association of cigarette price differentials with infant mortality in 23 European Union countries. JAMA Pediatr 171:1100–1106

Tsampi A (2021) Dataset: Novel Smoke Free Zones. DataverseNL. https://dataverse.nl/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.34894/FK8YKR. Accessed 16 April 2021

Radó MK, Mölenberg FJ, Westenberg LEH, Sheikh A, Millett C, Burdorf A, Van Lenthe FJ, Been JV (in press) Impact of smoke-free policies in outdoor areas and (semi-)private places on children’s tobacco smoke exposure and respiratory health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health

Faber T, Mizani MA, Sheikh A, Mackenbach JP, Reiss IK, Been JV (2019) Investigating the effect of England’s smoke-free private vehicle regulation on changes in tobacco smoke exposure and respiratory disease in children: a quasi-experimental study. Lancet Public Health 4:e607–e617

World Health Organization regional Office for Europe (2017) Tobacco-free generations. Protecting children from tobacco in the WHO European Region. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/tobacco/publications/2017/tobacco-free-generations-protecting-children-from-tobacco-in-the-who-european-region-2017. Accessed 16 April 2021

Shortt NK, Tisch C, Pearce J, Richardson EA, Mitchell R (2016) The density of tobacco retailers in home and school environments and relationship with adolescent smoking behaviours in Scotland. Tob Control 25:75–82

Laverty AA, Vamos EP, Millett C, Chang KCM, Filippidis FT, Hopkinson NS (2019) Child awareness of and access to cigarettes: impacts of the point-of-sale display ban in England. Tob Control 28:526–531

Robertson L, Cameron C, McGee R, Marsh L, Hoek J (2016) Point-of-sale tobacco promotion and youth smoking: a meta-analysis. Tob Control 25:e83–e89

DiFranza JR (2012) Which interventions against the sale of tobacco to minors can be expected to reduce smoking? Tob Control 21:436–442

MacGregor A, Delaney H, Amos A, Stead M, Eadie D, Pearce J, Ozakinci G, Haw S (2020) ‘It’s like sludge green’: young people’s perceptions of standardized tobacco packaging in the UK. Addiction 115:1736–1744

Been JV, Sheikh A (2018) Tobacco control policies in relation to child health and perinatal health outcomes. Arch Dis Child 103:817–819

Nabi-Burza E, Drehmer JE, Hipple Walters B, Rigotti NA, Ossip DJ, Levy DE, Klein JD, Regan S, Gorzkowski JA, Winickoff JP (2019) Treating parents for tobacco use in the pediatric setting: the clinical effort against secondhand smoke exposure cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 173:931–939

Scheffers-van Schayck T, Mujcic A, Otten R, Engels R, Kleinjan M (2020) The effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions tailored to smoking parents of children aged 0-18 years: a meta-analysis. Eur Addict Res:1-16

Pärna K, Põld M, Ringmets I (2017) Trends in smoking behaviour among Estonian physicians in 1982-2014. BMC Public Health 18:55

Juranić B, Rakošec Ž, Jakab J, Mikšić Š, Vuletić S, Ivandić M, Blažević I (2017) Prevalence, habits and personal attitudes towards smoking among health care professionals. J Occup Med Toxicol 12:20

Gispen ME, Toebes B (2019) The human rights of children in tobacco control. Hum Rights Q 41:340–373

van der Eijk Y, Porter G (2015) Human rights and ethical considerations for a tobacco-free generation. Tob Control 24:238–242

Romeo-Stuppy K, Dresler C, Bostic C, Healton C, Huber L, Lando H, Raw M (2020) The urgent need for a human rights approach to improving smoking cessation treatment. Tobacco Control Blog. BMJ. https://blogs.bmj.com/tc/2020/07/18/the-urgent-need-for-a-human-rights-approach-to-improving-smoking-cessation-treatment. Accessed 16 April 2021

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (1989) Convention on the rights of the child. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx. Accessed 7 May 2021

Council of Europe. The European Social Charter. https://www.coe.int/en/web/european-social-charter. Accessed 7 May 2021

European Committee of Social Rights (1994) Conclusions XIII-2 - Belgium - Article 7-10. XIII-2/def/BEL/7/10/EN

European Committee of Social Rights (2005) Conclusions XVII-2 - Malta - Article 11-3. XVII-2/def/MLT/11/3/EN

European Committee of Social Rights (2005) Conclusions XVII-2 - Portugal - Article 11-3. XVII-2/def/PRT/11/3/EN

European Committee of Social Rights (2001) Conclusions XV-2 - Greece - Article 11-3. XV-2/def/GRC/11/3/EN

Garde A, Toebes B (2020) Is there a European human rights approach to tobacco control? In: Gispen ME, Toebes B (eds) Human rights in tobacco control. Elgar, Cheltenham

European Court of Human Rights, Council of Europe (2013) European Convention on Human Rights. https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/convention_eng.pdf. Accessed 7 May 2021

(2012) Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A12012P%2FTXT. Accessed 7 May 2021

Tsampi A (in press) The European Court of Human Rights and (Framework Convention on) Tobacco Control: a relationship that goes up in smoke? European Convention on Human Rights Law Review

Tsampi A (2020) Novel Smoke-free Zones and the Right to Respect for Private Life under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (on the occasion of the Dutch Decree of 22 June 2020, amending the Tobacco and Smokers’ Order introducing the obligation to impose, designate and enforce a smoking ban in the areas belonging to buildings and facilities used for education). Europe of Rights & Liberties/Europe des Droits & Libertés 2:381–398

Hadjipanayis A, Stiris T, del Torso S, Mercier J-C, Valiulis A, Ludvigsson J (2017) Europe needs to protect children and youths against secondhand smoke. Eur J Pediatr 176:145–146

Department of Health and Social Care (2017) Towards a smokefree generation. A tobacco control plan for England. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/630217/Towards_a_Smoke_free_Generation_-_A_Tobacco_Control_Plan_for_England_2017-2022__2_.pdf. Accessed 16 April 2021

Ministry of Health Welfare and Sports (2019) The national Prevention Agreement. A healthier Netherlands. https://www.government.nl/documents/reports/2019/06/30/the-national-prevention-agreement. Accessed 16 April 2021

Funding

Lung Foundation Netherlands, Dutch Cancer Society, Dutch Heart Foundation, Dutch Diabetes Research Foundation and the Netherlands Thrombosis Foundation (grant number 2.1.19.010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and have read and approved its final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The authors have no other financial relationship with the funders. The funders were not involved in the preparation of this manuscript.

Additional information

Communicated by Peter de Winter

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Been, J.V., Laverty, A.A., Tsampi, A. et al. European progress in working towards a tobacco-free generation. Eur J Pediatr 180, 3423–3431 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-04116-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-04116-w