Abstract

Preparing for future scenarios in pediatric palliative care is perceived as complex and challenging by both families and healthcare professionals. This interpretative qualitative study using thematic analysis aims to explore how parents and healthcare professionals anticipate the future of the child and family in pediatric palliative care. Single and repeated interviews were undertaken with 42 parents and 35 healthcare professionals of 24 children, receiving palliative care. Anticipating the future was seen in three forms: goal-directed conversations, anticipated care, and guidance on the job. Goal-directed conversations were initiated by either parents or healthcare professionals to ensure others could align with their perspective regarding the future. Anticipated care meant healthcare professionals or parents organized practical care arrangements for future scenarios with or without informing each other. Guidance on the job was a form of short-term anticipation, whereby healthcare professionals guide parents ad hoc through difficult situations.

Conclusion: Anticipating the future of the child and family is mainly focused on achievement of individual care goals of both families and healthcare professionals, practical arrangements in advance, and short-term anticipation when a child deteriorates. A more open approach early in disease trajectories exploring perspectives on the future could allow parents to anticipate more gradually and to integrate their preferences into the care of their child.

What is Known: • Anticipating the future in pediatric palliative care occurs infrequently and too late. | |

What is New: • Healthcare professionals and parents use different strategies to anticipate the future of children receiving palliative care, both intentionally and unwittingly. Strategies to anticipate the future are goal-directed conversations, anticipated care, and guidance on the job. • Parents and healthcare professionals are engaged to a limited extent in ongoing explorative conversations that support shared decision-making regarding future care and treatment. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The number of children with life-limiting or life-threatening conditions (Box 1) is increasing as current medical treatment options allow critically ill children to live longer, being dependent on high-complex care for a longer period of time and expanding care facilities at home [1,2,3,4]. These children are in need of pediatric palliative care (PPC) from the point of diagnosis and continued throughout the child’s life and death [1, 5]. During different disease trajectories, preparing for future scenarios is perceived as complex and challenging by both families and healthcare professionals (HCPs) [6,7,8,9]. For parents, facing the future is emotionally challenging as it confronts them with the possible loss of their child [9, 10]. By discussing the future with families, HCPs fear to take away hope and disturb the families’ way of coping with the serious illness of their child [7, 8]. These factors may result in refraining from facing the future leading to a delayed initiation of PPC and insufficient attention to the child’s quality of life (QoL), especially at the end-of-life [11]. However, growing evidence shows that both families and HCPs value strategies to explore future scenarios in advance [10, 12,13,14,15]. In recent literature, there is growing interest in the concept of advance care planning (ACP) as a strategy to identify goals and preferences for future care and treatment, to share these thoughts between families and HCPs and document any preferences if considered appropriate [16]. Yet, it is known that ACP in pediatrics occurs infrequently and often too late due to barriers on the level of families, HCPs, and healthcare organizations [6,7,8, 13]. Limited research is done on current strategies of facing the future as used by HCPs and families when caring for a seriously ill child. We hypothesize that different ways of anticipating the future of the child and family may occur. Insight in current approaches of anticipating the future in PPC is needed. Based on these insights, strategies can be further developed to elicit individual family’s values and preferences for future care and treatment in order to support high quality family-centered care from diagnosis of a life-limiting condition until the end-of-life. Therefore, this study aims to explore how parents and HCPs currently anticipate the future of the child and family in PPC.

Box 1 Definitions [1]

Life-limiting disease: conditions for which are that there is no reasonable hope of a cure and from which children or young people will die. Life-threatening disease: conditions for which are that curative treatment can be feasible but can fail. |

Methods

Study design

As part of a larger study exploring the lived experience of families receiving PPC and their HCPs involved, an explorative qualitative study was conducted using inductive thematic analysis to elucidate approaches of anticipating the future of the child and family among parents and HCPs. The research ethics committee of the Academic Medical Centre Amsterdam approved the study (2013; Reference number: W13_120#13.17.0153). All participants gave written informed consent.

Sample

Parents of children with a life-limiting condition, receiving care from the pediatric palliative care team (PPCT) of the Emma Children’s Hospital, were purposefully selected. Maximum variation was sought with respect to the child’s diagnosis, age, and disease trajectory, including end-of-life [17,18,19]. Parents could also be included after the child’s death to achieve insight in very last period of life. PPCT case managers as well as other HCPs most involved in each selected case were also recruited.

Data collection

Parents were individually interviewed at home and HCPs at their workplace or by telephone between August 2013 and January 2016. Interviews lasted from 30 min to 2 h. They were conducted by independent researchers (LV, MK, MB) from a university hospital other than where the PPCT was established. A topic list based on literature and expert knowledge guided each interview (Supplementary information; Topic list 1 and 2). The interviewer explored how and to what extend parents and HCPs anticipated the future of the child and family in PPC and how they experienced this. Audio recordings of the interviews were anonymously transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

The data was analyzed using inductive thematic analysis [20,21,22]. Validity was ensured by a rigorous study design and repetitive meetings of the research team (LV, JF, SS, and MK). An audit trail recording methodological choices and substantive ideas and concepts related to the interpretation of the data was used to further ensure validity and provide transparency of the results.

The analysis yielded four steps. First, transcripts of five cases were (re)read to gain an overall understanding of the study objectives in context of the interviews. Meaningful fragments were identified in all five interviews. These fragments were coded in a data-driven manner (LV, SS, and MK) [20]. Second, of each interview, a narrative report was made to summarize strategies to approach future care. Fragments, initial codes, and summaries were compared and discussed aimed at reaching consensus in interpretation. The initial codes were combined, recoded, and adapted towards a code tree with themes and concepts at a more abstract and conceptual level. Third, all interviews were coded using NVivo10 [23]. After coding each case, the coding tree was evaluated and, if indicated, revisited. Fourth, based on the code tree, potential themes were identified. These were consistently verified, reviewed, and refined on coherency by constant comparison of the data per theme and of the whole thematic map in relation to all the data [21]. Saturation was reached at a conceptual level [24]. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research was used to structure the report [25].

Results

Of the 35 cases eligible for participation, 24 were included, resulting in the participation of 42 parents (24 mothers and 18 fathers) and 35 HCPs. Reasons for non-participation were parental refusal (n = 5) and HCPs considering a case too vulnerable to participate (n = 6). Three cases were included after the child’s death (parents, n = 6; HCPs, n = 10) and in three other cases, a repeated interview with the parents (n = 5) and with HCPs (n = 7) was done after the child’s death. Several HCPs were involved in multiple cases and, thus, interviewed several times. In total, 105 semi-structured interviews were conducted (parents, n = 47; HCPs, n = 58). For participant characteristics, see Tables 1 and 2.

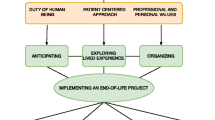

Anticipating the future

Many parents and HCPs experienced anticipation of the future of the child and family as difficult because of uncertainties due to the unpredictability of the disease course. Moreover, it required acknowledgement of disease progression and facing the child’s inevitable death. Despite these difficulties, parents as well as HCPs were seen to anticipate future care and treatment. Initiatives to share perspective were predominantly aimed at ensuring the child’s quality of life and comfort, also during the end-of-life. However, individual perspectives regarding the future were not shared between parents and HCPs to a large extent. Three forms of future anticipation were revealed: goal-directed conversations (GDC), anticipated care (AC), and guidance on the job (GOTJ). For illustrating quotes, see Table 3.

Goal-directed conversations

Initial conversations, both initiated by HCPs or parents, on future care and treatment as a way of sharing each other’s perspectives appeared not to occur naturally. Rather, these conversations regarding future scenarios had a conscious and goal-directed intention. In order to align the perspective on future care and treatment, both HCPs and parents shared their views on care and treatment in the future to the other party in the conversation. Initiation of such a conversation and mutual alignment of these care goals proved essential to influence the other party’s willingness to adapt their perspective and actions.

HCPs

Usually HCPs took the initiative to start a conversation regarding future care or treatment. HCPs mentioned to initiate a conversation about future care and treatment driven by ethical reasons, such as to prevent medically futile treatments or to ask consent for advance directives. They mentioned practical conversation goals as well, such as to have clarity about the preferred place of death. Although HCPs mentioned to explore the parents’ perspective in the conversation, they reported to have clear ideas about future care and treatment in advance. These care goals from the HCP’s perspective were mostly based on their own perspectives or on discussions within the medical team.

Besides their aim for getting parental consent on future care and treatment options, HCPs mentioned talking about the future were also aimed at preparing parents for difficult decision-making to be expected in the future. Some HCPs mentioned to initiate a conversation about the future, when they felt the parent had an unrealistic and too positive view on their child’s condition.

In order to create a shared perspective on the child’s condition, HCPs marked new stages of the disease trajectory in goal-directed conversations by emphasizing a concrete or objective aspect in the child’s condition or disease trajectory that clearly indicates that the child had entered or will enter in the future a new stage in the disease trajectory. This required from parents to reconsider their views on future care. HCPs either marked actual situations in the moment or prepared parents to expect marking moments in the future. Examples were the failure of cancer treatment indicating a shift from disease-directed treatment towards symptom-directed treatment or a hospital admission due to deterioration of the child, indicating the child’s increased vulnerability. Based on these marked new stages of the disease trajectory, HCPs framed parents by discussing the child’s condition in relation to these different stages and possible options for care and treatment, in order to clarify consequences for the child, for example, framing the high likelihood of a pediatric intensive care unit admission when continuing treatment or the negative consequences of resuscitating children given their condition.

Parents

Parents took the initiative to start a conversation about the future of their child in order to achieve a good life for their child with the least amount of suffering as possible. Another reason to discuss their future with HCPs could be parental goals of continuing regular family life and to receive clues around the prognosis of their child based on the HCPs’ expertise. Parents needed the knowledge and insights of the HCP to be able to arrange the care for their child for a longer period of time and to be able to develop their perspectives on family planning. Parents also needed the HCP’s formal approval to get access to care arrangements, such as modifications to their homes. The abovementioned goals were mainly reported by parents with a focus on prolonging the child’s life as well as by parents with a perceived longer life expectancy of their child.

Those parents who had a focus on comfort care without striving for prolonging life initiated conversations about their child’s future to be able to cope with their own ongoing loss. Some parents reported to start a conversation about future care in order to prevent their child’s suffering and unnecessary prolongation of life. These parents sought HCPs’ expertise, guidance, and agreement on limitation of life-sustaining treatments and options to allow a natural death. Parents whose HCP had been easily approachable felt more openness to ask questions about delicate issues, such as when to stop tube feeding and what could occur during the dying phase of the child. Some parents reported that HCPs had not been open for exploring the future or answering their questions, mainly by referring to prognostic uncertainty.

Few parents reported to initiate a conversation about the future aimed at reconsidering prior treatment limitations written down in an advance directive. These parents had observed a clear, yet unexpected improvement in the child’s condition, which in their opinion justified revisiting treatment limitations. Some parents framed the new situation towards HCPs as they felt a need to place the child’s condition in relation to a broader contact of disease course and treatment options. As such, they tried to convince HCPs to align to their perspective and goal setting as a parent with expertise on their child’s condition. Parents felt a need to place the child’s condition in relation to a broader context of disease course and treatment options in order to convince HCPs to align to their perspective and goal setting as a parent with expertise on their child’s condition.

Overall, the parents’ way of coping with the future loss of their child influenced their ability to discuss future care and treatment. Parents, who tend to focus on the “here-and-now” to be able to cope with feelings of loss and the daily burden of care, experienced difficulties or refused to discuss future care and treatment with HCPs.

Anticipated care

AC involved being prepared for future scenarios by shaping and organizing care arrangements in advance, in response to anticipated future needs of the child or family. AC occurred during the different disease stages in a similar way, although the content of AC might vary according to the focus of care, the changes in the child’s condition, and the preferences of the child and family. AC was mostly initiated by HCPs and sometimes by parents. It had either a “closed” or “open” character depending on whether HCPs or parents informed each other about the care arrangements made. Disclosure of “closed” AC occurred when a need arose among either HCPs or parents to inform each other about the preparations.

HCPs

AC was mainly conducted by HCPs experienced in PPC, such as PPCT members or pediatric homecare nurses, and often discussed among HCPs preparing for future care without informing the parents at the time. Examples included ordering medications and equipment for the home setting, creating a contact plan for parents, and involving other important HCPs, such as the PPCT, general practitioner, psychologist, or child-life specialist. HCPs often started with “closed” AC, mainly to prevent unnecessary burden to the parents or to prevent disruption of the parental coping strategy. Disclosure of “closed” AC occurred when parents were perceived as ready for the intended care arrangements or when the HCPs perceived the child’s or the parents’ interest as threatened when withholding the planned care. The tuning and timing when to provide insight in “closed” AC arrangements were experienced as a delicate task, preventing that care would be provided too late or started too early.

Parents

Only a few parents seemed to prepare for the future by organizing care arrangements in advance. Parents also used “closed” or “open” AC. Parents only informed HCPs when HCPs invited them to do so or when parents needed help from HCPs to arrange the care they aimed for. An example of “closed” AC performed by parents is organizing their child’s funeral in advance without mentioning this to their HCP. An illustration of “open” AC was a mother requesting a resuscitation course from the pediatrician to become able to take care of her daughter at home during an emergency.

Guidance on the job

GOTJ was discerned as a form of short-term anticipation on scenarios or symptoms to be expected in the near future. This form of anticipating the future was only conducted by HCPs. HCPs guided parents by explicitly informing them about the child’s current situation and short-term expectations thereof, indicating the necessity why certain actions or approaches were required now or in the near future. In this way, HCPs aimed to prepare parents what to expect among the deterioration of their child and needed care and how to act in the expected situation.

Most examples of GOTJ were related to moments of acute deterioration of the child or situations where death was imminent. HCPs used GOTJ to help parents to provide care aligned to the child’s altered needs. It was done in situations where parents seemed to be at risk to overlook new care needs of the child or felt unable to adequately respond to them. This could be a result either of inexperience or of difficulties in coping with the child’s end-of-life. This included for example being afraid to hasten the child’s death by starting morphine of withdrawal of feeding. GOTJ was both child-focused, aimed at improving the child’s comfort, as well as parent-focused, aimed at coaching and supporting parents to “be there” for their child and to act in the best interest of their child in situations that were difficult to predict or hardly bearable.

Parents indicated appreciation of GOTJ. It made them feel supported and helped them to cope with uncertain future scenarios. It prepared and enabled them to go through difficult steps in the disease trajectory of their child. Some parents felt relieved that HCPs took the lead to proceed in the end-of-life process, not wanting the final responsibility for decisions regarding the child’s end-of-life, such as treatment limitations, start of palliative sedation, or end of feeding.

Discussion

Parents and HCPs faced the future of the child and family to a various extent when caring for a child receiving palliative care. Parents and HCPs anticipated the future in order to safeguard the child’s quality of life, comfort, and quality of death, and to maintain family balance. Three forms of anticipating the future were identified: goal-directed conversations, anticipated care, and guidance on the job. The parents’ coping with the anticipated loss of their child’s abilities and, ultimately, their child’s life and the expertise of HCPs to support parents in facing the future largely influenced the occurrence of GDC and the need for AC and GOTJ.

In current research and practice in the field of PPC, there is a growing interest in strategies to anticipate the future in an adequate way [26]. Tools are developed to support families and HCPs in anticipating the future by ACP [27, 28]. Our study reveals some key points that show why implementation of ACP and other strategies to anticipate the future need ongoing attention.

A central element of newly developed ACP strategies is the identification of individual values and preferences that can inform shared decision-making about goals of future care and treatment. In the cases in the current study, anticipating the future in an open and explorative way aimed at the identification of patient values occurred to a limited extent. This study also showed that currently parents and HCPs shared future perspectives mainly when they considered it necessary to safeguard care goals or because the involvement of the other was indispensable. Consequently, these conversations of sharing future perspectives rather had a directional, than an open, explorative character. Given the current family-centered ideal of providing PPC [1, 5], anticipating the future might need strategies to explore families’ values and preferences for future care, in addition to a goal-directed approach as conducted currently by HCPs as observed in our study [13, 16]. An open and explorative approach could facilitate shared decision-making and allow for an earlier and more gradual integration of families’ values and preferences in future care and treatment as is aimed for in ACP. It is known that parents value ACP, yet they might hesitate to share their values and preferences for their child’s care and treatment by themselves [9, 29, 30]. Families often wait for the HCP to start conversations about future care [31, 32]. As such, it might be helpful when ACP tools support HCPs to invite parents for ACP conversations and help them to achieve an open and explorative approach when anticipating the future in conversations.

It is known that parents experience anticipating the future as an inevitable part of seeking good care for their child, although it confronts them with ongoing losses [9, 10, 33]. Our study showed that all parents, even parents who coped with distress by living day-by-day in the present, regularly had thoughts about their child’s anticipated early death. This knowledge should stimulate HCPs to explore these perspectives and open up a conversation about what is important to families facing the child’s possible death. Also uncertainty due to the unpredictable course of the disease [6, 8, 9, 18], which is known as a barrier to anticipate the future for both parents and HCPs, should rather be a trigger for conversations about future care and treatment in order to start these conversations in time, as also previously argued by Kimbell et al. [29]. Timely initiation of these conversations would allow parents a well-timed transition from an attitude of preserving their child at all costs towards letting go when time has come [30].

From our study, we could identify GDC, AC, and GOTJ as three separate forms to anticipate future care and treatment. In practice, these three forms may intermingle, occur simultaneously, and ideally merge into each other. All strategies can be part of an ACP process, in which different phases in the child’s disease trajectory lead to different coping mechanisms requiring a specific approach. For example, during the end of life of the child or an acute deterioration of the child’s condition, families might need more guidance from HCPs, requiring GOTJ. In cases with little or no GDC or AC, occurrence of GOTJ was more prominent and required HCPs to keep track of the child’s situation more actively to identify any changes in time. If GOTJ was not performed actively, adequate childcare could be addressed too late, again emphasizing the importance of timely initiation of ACP [29, 30]. Ideally, GOTJ can consecutively build on earlier GDC and benefit from well-organized AC. AC that was based on the HCPs’ or parents’ own perspective mainly could be better aligned to the child’s and family’s needs and wishes when prior conversations had elicited their values. As such, GDC, AC, and GOTJ ideally co-exist and will rely on prior discussions and to the child’s and family’s actual needs. Moreover, well-performed anticipation of the future of the child and family by both parents and HCPs offers an important fundament for shared decision-making [12].

Kimbell et al. and other studies [8, 29] also highlighted the importance of a continuing process in ACP, with regular reviewing preferences and goals of care. In this study, parents initiated revisions of previously made agreements, such as advance directives, when they saw their child’s condition improved. HCPs regularly discussed the child’s current state with parents but whether they monitored changes in parents’ perspectives on future care and treatment was less clear. Research for future ACP interventions can investigate how to incorporate regular monitoring and, if needed, revisions of preferences for care and treatment.

This study had some strengths and limitations. Being a one-centered study, the generalizability of our results might be limited. Nevertheless, purposeful sampling facilitated a wide variation regarding diagnosis, age, and phase of palliative trajectory. This research also offers a broad and diverse perspective on data from 24 cases crossing different age groups and including insights of both parents and HCPs. Some HCPs regarded few eligible parents to be too burdened to participate, preventing or delaying their inclusion. This is known as gatekeeping and often seen in palliative care research [34]. This aspect might have resulted in an overestimation of the occurrence of GDC, AC, and GOTJ and an underestimation of parents who have difficulties to anticipate future care. We did not capture differences in cultural and religious aspects, which is a limitation because there are cultural differences in decision-making and communication styles [35]. Our findings might be limited by not analyzing recordings of the actual conversations between parents and HCPs; however, the interviews were believed to give valuable insights into perspectives regarding anticipation of the future. Future research could focus on the implementation of ACP to anticipate the future of the child and family in a more comprehensive way, while exploring values and preferences for the future without any need for achieving goals, decision-making, or arranging care at that moment. Perspectives shared in ACP can function as a foundation for the content of GDC, AC, and GOTJ, which might remain necessary in certain situations, even when adequate ACP occurred in advance.

Conclusion

This study showed that parents and HCPs anticipate the future of the child and family in PPC mainly by GDC, AC, and GOTJ. Sharing of future perspectives often occurred with the intention to achieve a self-defined individual goal in the care for the child, by either the HCP or the parent. The extent of sharing future perspectives was influenced by the parents’ ability to cope with ongoing and, in particular, anticipated loss and the HCPs’ perception thereof. In addition to a goal-directed approach, a more open approach exploring mutual perspectives on future care and treatment could improve timely anticipation of future care needs of the child and family and allow parents to anticipate the future more gradually.

Abbreviations

- AC:

-

Anticipated care

- ACP:

-

Advance care planning

- GDC:

-

Goal-directed conversation

- GOTJ:

-

Guidance on the job

- HCP:

-

Healthcare professional

- PPC:

-

Pediatric palliative care

- PPCT:

-

Pediatric palliative care team

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

References

Chambers L (2018) A guide to children’s palliative care, 4th edn. Together for short lives, Bristol

IOM (2015) Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Mellor C, Heckford E, Frost J (2012) Developments in paediatric palliative care. Paediatr Child Health (Oxford) 22:115–120

Feudtner C, Kang TI, Hexem KR, Friedrichsdorf SJ, Osenga K, Siden H, Friebert SE, Hays RM, Dussel V, Wolfe J (2011) Pediatric palliative care patients: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Pediatrics 127:1094–1101

American Academy of Pediatrics (2000) Palliative care for children. Pediatrics 106:351–357

Durall A, Zurakowski D, Wolfe J (2012) Barriers to conducting advance care discussions for children with life-threatening conditions. Pediatrics 129:e975–e982

Sanderson A, Hall AM, Wolfe J (2016) Advance care discussions: pediatric clinician preparedness and practices. J Pain Symptom Manag 51:520–528

Lotz JD, Jox RJ, Borasio GD, Führer M (2015) Pediatric advance care planning from the perspective of health care professionals: a qualitative interview study. Palliat Med 29:212–222

Lotz JD, Daxer M, Jox RJ, Borasio GD, Führer M (2017) “Hope for the best, prepare for the worst”: a qualitative interview study on parents’ needs and fears in pediatric advance care planning. Palliat Med 31:764–771

Fahner JC, Thölking TW, Rietjens JAC, van der Heide A, van Delden JJM, Kars MC (2020) Towards advance care planning in pediatrics: a qualitative study on envisioning the future as parents of a seriously ill child. Eur J Pediatr 179:1461–1468

Davies B, Sehring SA, Partridge JC, Cooper BA, Hughes A, Philp JC, Amidi-Nouri A, Kramer RF (2008) Barriers to palliative care for children: perceptions of pediatric health care providers. Pediatrics 121:282–288

DeCourcey DD, Silverman M, Oladunjoye A, Wolfe J (2019) Advance care planning and parent-reported end-of-life outcomes in children, adolescents, and young adults with complex chronic conditions. Crit Care Med 47:101–108

Fahner JC, Beunders AJM, van der Heide A, Rietjens JAC, Vanderschuren MM, van Delden JJM, Kars MC (2019) Interventions guiding advance care planning conversations: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 20:227–248

Hein K, Knochel K, Zaimovic V, Reimann D, Monz A, Heitkamp N, Borasio GD, Führer M (2020) Identifying key elements for paediatric advance care planning with parents, healthcare providers and stakeholders: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 34:300–308

Orkin J, Beaune L, Moore C, Weiser N, Arje D, Rapoport A, Netten K, Adams S, Cohen E, Amin R (2020) Toward an understanding of advance care planning in children with medical complexity. Pediatrics 145:e20192241

Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, van Delden J, Drickamer MA, Droger M, van der Heide A, Heyland DK, Houttekier D, Janssen DJA, Orsi L, Payne S, Seymour J, Jox RJ, Korfage IJ, European Association for Palliative Care (2017) Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol 18:e543–e551

Verberne LM, Kars MC, Schouten-van Meeteren AYN et al (2017) Aims and tasks in parental caregiving for children receiving palliative care at home: a qualitative study. Eur J Pediatr 176:343–354

Kars MC, Grypdonck MHF, van Delden JJM (2011) Being a parent of a child with cancer throughout the end-of-life course. Oncol Nurs Forum 38:E260–E271

Wood F, Simpson S, Barnes E, Hain R (2010) Disease trajectories and ACT/RCPCH categories in paediatric palliative care. Palliat Med 24:796–806

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101

Dierckx de Casterle B, Gastmans C, Bryon E, Denier Y (2012) QUAGOL: a guide for qualitative data analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 49:360–371

Thomas DR (2006) Method notes a general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval 27:237–246

(2010) NVivo qualitative data analysis software. [Computer Program].Version 10

Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC (2017) Code saturation versus meaning saturation. Qual Health Res 27:591–608

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Heal Care

Myers J, Cosby R, Gzik D, Harle I, Harrold D, Incardona N, Walton T (2018) Provider tools for advance care planning and goals of care discussions: a systematic review. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 35:1123–1132

Fahner J, Rietjens J, van der Heide A, et al (2020) Evaluation showed that stakeholders valued the support provided by the Implementing Pediatric Advance Care Planning Toolkit. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr 1–9

van Breemen C, Johnston J, Carwana M, Louie P (2020) Serious illness conversations in pediatrics: a case review. Children 7:102

Kimbell B, Murray SA, Macpherson S, Boyd K (2016) Embracing inherent uncertainty in advanced illness. BMJ 354:i3802

Rosenberg AR, Wolfe J, Wiener L, Lyon M, Feudtner C (2016) Ethics, emotions, and the skills of talking about progressing disease with terminally ill adolescents: a review. JAMA Pediatr 170:1216–1223

Erby LH, Rushton C, Geller G (2006) “My son is still walking”: stages of receptivity to discussions of advance care planning among parents of sons with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Semin Pediatr Neurol 13:132–140

Wharton RH, Levine KR, Buka S, Emanuel L (1996) Advance care planning for children with special health care needs: a survey of parental attitudes. Pediatrics 97:682–687

Verberne LM, Kars MC, Schouten-van Meeteren AYN et al (2019) Parental experiences and coping strategies when caring for a child receiving paediatric palliative care: a qualitative study. Eur J Pediatr 178:1075–1085

Kars MC, van Thiel GJMW, van der Graaf R, Moors M, de Graeff A, van Delden JJM (2016) A systematic review of reasons for gatekeeping in palliative care research. Palliat Med 30:533–548

Wiener L, McConnell DG, Latella L, Ludi E (2013) Cultural and religious considerations in pediatric palliative care. Palliat Support Care 11:47–67

Acknowledgments

We thank all the parents who participated in this study. We also thank Madelief Buijs for conducting the first interviews.

Funding

The study was funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), Grant Number 82-82100-98-208.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Lisa Verberne, Jurrianne Fahner, Stephanie Sondaal and Marijke Kars. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Lisa Verberne, Jurrianne Fahner and Stephanie Sondaal and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by Peter de Winter

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 15.3 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Verberne, L.M., Fahner, J.C., Sondaal, S.F.V. et al. Anticipating the future of the child and family in pediatric palliative care: a qualitative study into the perspectives of parents and healthcare professionals. Eur J Pediatr 180, 949–957 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-020-03824-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-020-03824-z