Abstract

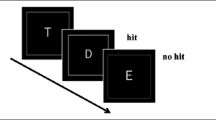

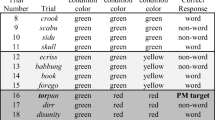

Remembering to perform a delayed intention is referred to as prospective memory (PM). In two studies, participants performed an Eriksen flanker task with an embedded PM task (they had to remember to press F1 if a pre-specified cue appeared). In study 1, participants performed a flanker task with either a concurrent PM task or a delayed PM task (instructed to carry out the intention in a later different task). In the delayed PM condition, the PM cues appeared unexpectedly early and we examined whether attention would be captured by the PM cue even though they were not relevant. Results revealed ongoing task costs solely in the concurrent PM condition but no significant task costs in the delayed PM condition showing that attention was not captured by the PM cue when it appeared in an irrelevant context. In study 2, we compared a concurrent PM condition (exactly as in Study 1) to a PM forget condition in which participants were told at a certain point during the flanker task that they no longer had to perform the PM task. Analyses revealed that participants were able to switch off attending to PM cues when instructed to forget the PM task. Results from both studies demonstrate the flexibility of monitoring as evidenced by the presence versus absence of costs in the ongoing flanker task implying that selective attention, like a lens, can be adjusted to attend or ignore, depending on intention relevance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

To check whether reaction times to PM cues initially started off slow in early trials and then eventually sped up, we divided the PM and Deviant trials into mini-blocks (of 4 trials each) for the PM Delayed condition in Experiment 1 and in the PM Forget condition in Experiment 2. We conducted Trial type (PM Cue vs. Deviant) × Miniblock (Miniblock 1 vs. 2) ANOVAs for both experiments. Results revealed that the interaction was far from significant in Experiment 1 (p = .89) and in Experiment 2 (p = .70). Furthermore, we computed contrasts between PM and deviant trials for the first mini block of trials and there was no significant difference for Experiment 1 (p = .30) or Experiment 2 (p = .40). These analyses confirm that even in the very first mini-block trials, reaction times to PM trials did not differ significantly from deviant trials when the intention was not active.

References

Bugg, J. M., & Scullin, M. K. (2013). The surprising ease of stopping after going relative to stopping after never having gone. Psychological Science,. doi:10.1177/0956797613494850.

Cohen, A.-L. (2013). Attentional decoupling while pursuing intentions: A form of mind wandering? Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 1–9. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00693.

Cohen, A.-L., Jaudas, A., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2008). Number of cues influences the cost of remembering to remember. Memory and Cognition, 36(1), 149–156. doi:10.3758/MC.36.1.149.

Cohen, A.-L., Jaudas, A., Hirschhorn, E., Sobin, Y., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2012). The specificity of prospective memory costs. Memory,. doi:10.1080/09658211.2012.710637.

Cohen-Kdoshay, O., & Meiran, N. (2007). The representation of instructions in working memory leads to autonomous response activation: Evidence from the first trials in the flanker paradigm. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 60, 1140–1154. doi:10.1080/17470210600896674.

Cohen-Kdoshay, O., & Meiran, N. (2009). The representation of instructions operates like a prepared reflex: Flanker compatibility effects found in first trial following S-R instructions. Experimental Psychology, 56, 128–133. doi:10.1027/1618-3169.56.2.128.

Cox, W. M., & Klinger, E. (2011). Handbook of motivational counseling: Goal-based approaches to assessment and intervention with addiction and other problems. Hoboken: Wiley.

Dreisbach, G. (2012). Mechanisms of cognitive control: The functional role of task rules. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21, 227–331.

Dreisbach, G., & Bäuml, K.-H. T. (2014). Don’t do it again… Directed forgetting of habits. Psychological Science, 25, 1242–1248.

Einstein, G. O., & McDaniel, M. A. (1990). Normal aging and prospective memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 16(4), 717.

Einstein, G. O., & McDaniel, M. A. (2005). Prospective memory: Multiple retrieval processes. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(6), 286–290.

Einstein, O., McDaniel, M., Thomas, R., Mayfield, S., Shank, H., Morrisette, N., & Breneiser, J. (2005). Multiple processes in prospective memory retrieval: Factors determining monitoring versus spontaneous retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 134, 327–342.

Eriksen, B. A., & Eriksen, C. W. (1974). Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Perception and Psychophysics, 16(1), 143–149. doi:10.3758/BF03203267.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

Hicks, J. L., Marsh, R. L., & Cook, G. I. (2005). An observation on the role of context variability in free recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 31(5), 1160–1164. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.31.5.1160.

Hommel, B. (2000). The prepared reflex—automaticity and control in stimulus-response translation. In S. Monsell & J. Driver (Eds.), Control of cognitive processes: Attention and performance XVIII (pp. 247–273). Cambridge: MIT Press.

James, W. (1950). The principles of psychology. New York: Dover. (Original work published 1890).

Knight, J. B., Meeks, J. T., Marsh, R. L., Cook, G. I., Brewer, G. A., & Hicks, J. L. (2011). An observation on the spontaneous noticing of prospective memory event-based cues. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37, 298–307. doi:10.1037/a0021969.

Liefooghe, B., Wenke, D., & De Houwer, J. (2012). Instruction-based task-rule congruency effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38, 1325–1335.

Lourenço, J. S., & Maylor, E. A. (2014). Is it relevant? Influence of trial manipulations of prospective memory context on task interference. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 67, 687–702.

Marsh, R. L., Cook, G. I., & Hicks, J. L. (2006). Task interference from event-based intentions can be material specific. Memory & Cognition, 34, 1636–1643.

McDaniel, M. A., & Einstein, G. O. (2007). Prospective memory: An overview and synthesis of an emerging field. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

Meiser, T., & Rummel, J. (2012). False prospective memory responses as indications of automatic processes in the initiation of delayed intentions. Consciousness and Cognition, 21, 1509–1516. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2012.05.006.

Posner, M. I. (1980). Orienting of attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32(1), 3–25. doi:10.1080/00335558008248231.

Rummel, J., & Meiser, T. (2015). Spontaneous prospective-memory processing: Unexpected fluency experiences trigger erroneous intention executions. Memory & Cognition,. doi:10.3758/s13421-015-0546-y.

Scullin, M. K., Bugg, J. M., & McDaniel, M. A. (2012). Whoops, I did it again: Commission errors in prospective memory. Psychology and Aging, 27, 46–53.

Scullin, M. K., McDaniel, M. A., Shelton, J. T., & Lee, J. H. (2010). Focal/nonfocal cue effects in prospective memory: Monitoring difficulty or different retrieval processes? Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36(3), 736–749. doi:10.1037/a0018971.

Smith, R. E. (2003). The cost of remembering to remember in event-based prospective memory: Investigating the capacity demands of delayed intention performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 29(3), 347–361. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.29.3.347.

Smith, R. E., & Bayen, U. J. (2004). A multinomial model of event-based prospective memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 30(4), 756–777. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.30.4.756.

Smith, R. E., Hunt, R. R., McVay, J. C., & McConnell, M. D. (2007). The cost of event-based prospective memory: Salient target events. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 33(4), 734–746. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.33.4.734.

Stone, M., Dismukes, K., & Remington, R. (2001). Prospective memory in dynamic environments: Effects of load, delay, and phonological rehearsal. Memory, 9, 165–176.

Walser, M., Fischer, R., & Goschke, T. (2012). The failure of deactivating intentions: Aftereffects of completed intentions in the repeated prospective memory cue paradigm. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38(4), 1030–1044. doi:10.1037/a0027000.

Waszak, F., Wenke, D., & Brass, M. (2008). Cross-talk of instructed and applied arbitrary visuomotor mappings. Acta Psychologica, 127, 30–35.

Wechsler, D. (1997). WAIS-III administration and scoring manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation.

Wenke, D., Gaschler, R., & Nattkemper, D. (2007). Instruction-induced feature-binding. Psychological Research, 71, 92–106.

Wenke, D., Gaschler, R., Nattkemper, D., & Frensch, P. A. (2009). Strategic influences on implementing instructions for future actions. Psychological Research, 73, 587–601.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We wish to thank Sarah Robinson for her dedicated assistance with data collection.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, AL., Gordon, A., Jaudas, A. et al. Let it go: the flexible engagement and disengagement of monitoring processes in a non-focal prospective memory task. Psychological Research 81, 366–377 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-016-0744-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-016-0744-7