Abstract

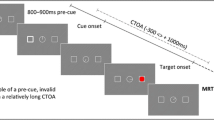

To explore the role of temporal context on voluntary orienting of attention, we submitted healthy participants to a spatial cueing task in which cue-target stimulus onset asynchronies (SOAs) were organized according to two-dimensional parameters: range and central value. Three ranges of SOAs organized around two central SOA values were presented to six groups of participants. Results showed a complex pattern of responses in terms of spatial validity (faster responses to correctly cued target) and preparatory effect (faster responses to longer SOAs). Responses to validly and neutrally cued targets were affected by the increase in SOA duration if the difference between longer and shorter SOA was large. On the contrary, responses to invalidly cued targets did not vary according to SOA manipulations. The observed pattern of cueing effects does not fit in the typical description of spatial attention working as a mandatory disengaging–shifting–engaging routine. In contrast, results rather suggest a mechanism based on the interaction between context sensitive top-down processes and bottom-up attentional processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

All statistical power analyses reported here were performed using the GPOWER program (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007).

In order to estimate the contribution of automatic sequential effects to the FP effect (see Los & Van den Heuvel, 2001), we made an analysis of the experimental findings that included the current SOA (short, central, long), the SOA of the previous trial, i.e., SOAn − 1 (short, central, long, catch), and cueing (valid, invalid, neutral, no cue) as within-subjects factors, and average SOA and SOA range as between-subjects variables. The ANOVA conducted on mean RTs revealed no contribution of SOAn − 1. SOAn − 1 had neither a main effect, F(3,108) = 1.69, nor did it interact with SOA in any case: SOAn – 1 × SOA, F(6,216) = 1; SOAn – 1 × SOA × range × average SOA, F < 1. Therefore, in this task, asymmetric sequential effects (see Los & Van den Heuvel, 2001), did not contribute to the foreperiod effect.

References

Alegria, J. (1974). The time course of preparation after a first peak: Some constraints of reacting mechanisms. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 26, 622–632.

Alegria, J., & Bertelson, P. (1970). Time uncertainty, number of alternatives and particular signal-response pair as determinants of choice reaction time. Acta Psychologica, 33, 36–44.

Cheal, M. L., & Lyon, D. R. (1991). Central and peripheral precuing of forced-choice discrimination. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 43A, 859–880.

Cheal, M. L., Lyon, D. R., & Gottlob, L. R. (1994). A framework for understanding the allocation of attention in location-precued discrimination. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 47, 699–739.

Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Corbetta, M., Patel, G., & Shulman, G. L. (2008). The reorienting system of the human brain: from environment to theory of mind. Neuron, 58(3), 306–324.

Correa, A., Lupiáñez, J., & Tudela, P. (2005). Attentional preparation based on temporal expectancy modulates processing at the perceptual-level. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12(2), 328–334.

Cui, X., Stetson, C., Montague, P. R., & Eagleman, D. M. (2009). Ready…go: Amplitude of the fMRI signal encodes expectation of cue arrival time. PLoS Biology, 7(8), e1000167.

Davis, G. J., & Gibson, B. S. (2012). Going rogue in the spatial cuing paradigm: High spatial validity is insufficient to elicit voluntary shifts of attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 38(5), 1192–1201.

Dosenbach, N. U. F., Fair, D. A., Cohen, A. L., Schlaggar, B. L., & Petersen, S. E. (2008). A dual-networks architecture of top-down control. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(3), 99–105.

Drazin, D. H. (1961). Effects of foreperiod, foreperiod variability, and probability of stimulus occurrence on simple reaction time. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62, 43–50.

Duncan, J., Ward, R., & Shapiro, K. (1994). Direct measurement of attentional dwell time in human vision. Nature, 369, 313–315.

Egeth, H. E., & Yantis, S. (1997). Visual attention: control, representation, and time course. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 269–297.

Elithorn, A., & Lawrence, C. (1955). Central inhibition: Some refractory observations. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 11, 211–220.

Elliott, R. (1973). Some confounding factors in the study of preparatory set in reaction time. Memory and Cognition, 1, 13–18.

Eriksen, C. W., & St. James, J. D. (1986). Visual attention within and around the field of focal attention: a zoom lens model. Perception and Psychophysics, 40, 225–240.

Fan, J., McCandliss, B. D., Sommer, T., Raz, A., & Posner, M. I. (2002). Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14, 340–347.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

Gabay, S., & Henik, A. (2010). Temporal expectancy modulates inhibition of return in a discrimination task. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 17(1), 47–51.

Gallistel, C. R., & Gibbon, J. (2000). Time, rate, and conditioning. Psychological Review, 107(2), 289–344.

Ghose, G. M., & Maunsell, J. H. R. (2002). Attentional modulation in visual cortex depends on task timing. Nature, 419, 616–620.

Gibbon, J., Church, R. M., & Meck, W. H. (1984). Scalar timing in memory. In J. Gibbon & L. G. Allan (Eds.), Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 423, Timing and time perception (pp. 52–77). New York: New York Academy of Sciences.

Girardi, G., Antonucci, G., & Nico, D. (2013). Cueing spatial attention through timing and probability. Cortex, 49(1), 211–221.

Gorea, A. (2011). Ticks per thought or thoughts per tick? A selective review of time perception with hints on future research. Journal of Physiology-Paris, 105, 153–163.

Grondin, S. (2001). From physical time to the first and second moments of psychological time. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 22–44.

Grondin, S. (2010a). Timing and time perception: A review of recent behavioral and neuroscience findings and theoretical directions. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 72(3), 561–582.

Grondin, S. (2010b). Unequal Weber fractions for the categorization of brief temporal intervals. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 72(5), 1422–1430.

Grondin, S., & Rammsayer, T. (2003). Variable foreperiods and temporal discrimination. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 56A, 731–765.

Hommel, B., Pratt, J., Colzato, L., & Godijn, R. (2001). Symbolic control of visual attention. Psychological Science, 12(5), 360–365.

Janssen, P., & Shadlen, M. N. (2005). A representation of the hazard rate of elapsed time in macaque area LIP. Nature Neuroscience, 8(2), 234–241.

Jongen, E. M. M., & Smulders, F. T. Y. (2007). Sequence effects in a spatial cueing task: endogenous orienting is sensitive to orienting in the preceding trial. Psychological Research, 71(5), 516–523.

Jonides, J. (1981). Voluntary versus automatic control over the mind’s eyes. In J. Long & A. Baddeley (Eds.), Attention and performance IX (pp. 187–203). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Karlin, L. (1959). Reaction time as a function of foreperiod duration and variability. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58, 185–191.

Klein, R., & Hansen, E. (1990). Chronometric analysis of apparent spotlight failure in endogenous visual orienting. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 16(4), 790–801.

Klemmer, E. T. (1956). Time uncertainty in simple reaction time. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 51, 179–184.

Lambert, A., Naikar, N., McLachlan, K., & Aitken, V. (1999). A new component of visual orienting: Implicit effects of peripheral information and subthreshold cues on covert attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 25, 321–340.

Los, S. A., & Schut, M. L. J. (2008). The effective time course of preparation. Cognitive Psychology, 57, 20–55.

Los, S. A., & Van Den Heuvel, C. E. (2001). Intentional and unintentional contributions of nonspecific preparation during reaction time foreperiods. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27(2), 370–386.

Müller, H. J., & Findlay, J. M. (1988). The effect of visual attention on peripheral discrimination thresholds in single and multiple element displays. Acta Psychologica, 69, 129–155.

Müller, H. J., & Rabbitt, P. M. A. (1989). Reflexive and voluntary orienting of visual attention: Time course of activation and resistance to interruption. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 15, 315–330.

Müller-Gethmann, H., Ulrich, R., & Rinkenauer, G. (2003). Locus of the effect of temporal preparation: evidence from the lateralized readiness potential. Psychophysiology, 40, 597–611.

Näätänen, R. (1970). The diminishing time-uncertainty with the lapse of time after the warning-signal in reaction time experiments with varying fore-periods. Acta Psychologica, 34, 399–419.

Näätänen, R. (1972). Time uncertainty and occurrence uncertainty of the stimulus in a simple reaction time task. Acta Psychologica, 36, 492–503.

Nakayama, K. (1990). The iconic bottleneck and the tenuous link between early visual processing and perception. In C. Blakemore (Ed.), Vision: Coding and efficiency (pp. 411–422). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nakayama, K., & Mackeben, M. (1989). Sustained and transient components of focal visual attention. Vision Research, 29, 1631–1647.

Niemi, P., & Näätänen, R. (1981). Foreperiod and simple reaction time. Psychological Bulletin, 89, 133–162.

Nobre, A. C., Correa, A., & Coull, J. T. (2007). The hazards of time. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 17, 1–6.

Petersen, S. E., & Posner, M. I. (2012). The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 35, 73–89.

Posner, M. I. (1980). Orienting of attention. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32, 3–25.

Posner, M. I., & Boies, S. J. (1971). Components of attention. Psychological Review, 78, 391–408.

Posner, M. I., & Cohen, Y. (1984). Components of visual orienting. In H. Bouma & D. G. Bouwhuis (Eds.), Attention and performance X (pp. 531–556). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Posner, M. I., Cohen, A., & Rafal, R. D. (1982). Neural systems control of spatial orienting. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, B, 298, 187–198.

Posner, M. I., Inhoff, A. W., Friedrich, F. J., & Cohen, A. (1987). Isolating attentional systems: a cognitive-anatomical analysis. Psychobiology, 15, 107–121.

Posner, M. I., & Petersen, S. E. (1990). The attention system of the human brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 13, 25–42.

Posner, M. I., Petersen, S. E., Fox, P., & Raichle, M. E. (1988). Localization of cognitive operations in the human brain. Science, 240, 1627–1631.

Posner, M. I., Snyder, C. R. R., & Davidson, B. J. (1980). Attention and detection of signals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 109(2), 160–174.

Ranzini, M., Dehaene, S., Piazza, M., & Hubbard, E. M. (2009). Neural mechanisms of attentional shifts due to irrelevant spatial and numerical cues. Neuropsychologia, 47(12), 2615–2624.

Raz, A., & Buhle, J. (2006). Typologies of attentional networks. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7, 367–379.

Sanders, A. F. (1966). Expectancy: application and measurement. Acta Psychologica, 25, 293–313.

Scharlau, I., Ansorge, U., & Horstmann, G. (2006). Latency facilitation in temporal-order judgments: time course of facilitation as a function of judgment type. Acta Psychologica, 122, 129–159.

Sperling, G., & Reeves, A. (1980). Measuring the reaction time of a shift of visual attention. In R. S. Nickerson (Ed.), Attention and performance VIII. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Steinborn, M. B., Rolke, B., Bratzke, D., & Ulrich, R. (2008). Sequential effects within a short foreperiod context: evidence for the conditioning account of temporal preparation. Acta Psychologica, 129, 297–307.

Theeuwes, J. (2010). Top-down and bottom-up control of visual selection. Acta Psychologica, 135, 77–99.

Thomas, E. A. (1967). Reaction-time studies: the anticipation and interaction of responses. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 20, 1–29.

Tipples, J. (2002). Eye gaze is not unique: automatic orienting in response to uninformative arrows. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9, 314–318.

Ward, R., Duncan, J., & Shapiro, K. (1996). The slow time-course of visual attention. Cognitive Psychology, 30, 79–109.

Wearden, J. H., & Ferrara, A. (1996). Stimulus range effects in temporal bisection by humans. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 49B, 24–44.

Wearden, J. H., & Lejeune, H. (2008). Scalar properties in human timing: conformity and violations. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61(4), 569–587.

Yantis, S. (1988). On analog movements of visual attention. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 43(2), 203–206.

Yantis, S. (1998). Control of visual attention. In H. Pashler (Ed.), attention (pp. 223–256). London, UK: University College Press.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by a grant from the Compagnia San Paolo di Torino, Programma Neuroscienze 2008/09 (TECRONE-project). The authors wish to thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and Dr. Elena Daprati for her suggestions and assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Girardi, G., Antonucci, G. & Nico, D. Timing the events of directional cueing. Psychological Research 79, 1009–1021 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-014-0635-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-014-0635-8