Abstract

Main conclusion

Our study demonstrated that the species respond non-linearly to increases in CO2 concentration when exposed to decadal changes in CO2, representing the year 1987, 2025, 2051, and 2070, respectively.

Abstract

There are several lines of evidence suggesting that the vast majority of C3 plants respond to elevated atmospheric CO2 by decreasing their stomatal conductance (gs). However, in the majority of CO2 enrichment studies, the response to elevated CO2 are tested between plants grown under ambient (380–420 ppm) and high (538–680 ppm) CO2 concentrations and measured usually at single time points in a diurnal cycle. We investigated gs responses to simulated decadal increments in CO2 predicted over the next 4 decades and tested how measurements of gs may differ when two alternative sampling methods are employed (infrared gas analyzer [IRGA] vs. leaf porometer). We exposed Populus tremula, Popolus tremuloides and Sambucus racemosa to four different CO2 concentrations over 126 days in experimental growth chambers at 350, 420, 490 and 560 ppm CO2; representing the years 1987, 2025, 2051, and 2070, respectively (RCP4.5 scenario). Our study demonstrated that the species respond non-linearly to increases in CO2 concentration when exposed to decadal changes in CO2. Under natural conditions, maximum operational gs is often reached in the late morning to early afternoon, with a mid-day depression around noon. However, we showed that the daily maximum gs can, in some species, shift later into the day when plants are exposed to only small increases (70 ppm) in CO2. A non-linear decreases in gs and a shifting diurnal stomatal behavior under elevated CO2, could affect the long-term daily water and carbon budget of many plants in the future, and therefore alter soil–plant–atmospheric processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The global land vegetation is a key driver in the hydrological and energy processes on our planet. The transfer of water from the soil, through the plants and into the atmosphere is regulated by stomatal pores on the leaf surface (Brodribb and McAdam 2017) and accounts for up to 80–90% of terrestrial evapotranspiration in some biomes (Jasechko et al. 2013). There are several lines of evidence suggesting that the vast majority of C3 plants respond to elevated CO2 by decreasing their stomatal conductance (gs) and rates of transpiration and by increasing their assimilation rates (A) and overall water use efficiency (WUE) (Ainsworth and Rogers 2007). Under extreme heat and aridity, gs can increase in response to elevated CO2 but a greater magnitude of A increase still results in improved WUE (Purcell et al. 2018). Anatomically, elevated CO2 has been shown to reduce stomatal density (Woodward 1987; Woodward and Kelly 1995; McElwain and Steinthorsdottir 2017) and in some cases alter stomatal pore size (decrease or increase), thereby reducing maximum gs to water vapor (Franks and Beerling 2009; Xu et al. 2016; Lammertsma et al. 2011). Stomatal physiological and anatomical responses to elevated CO2 have been shown to be coordinated (Haworth et al. 2013) and are dependent on the growth environment of the plant (Curtis and Wang 1998) and the plant’s underlying degree of plasticity and/or capacity to physiologically acclimate (Stitt and Krapp 1999; Ainsworth and Long 2005). The synergistic/antagonistic effects of other abiotic (e.g., light, vapor pressure deficit [VPD], soil moisture, nutrients etc.) and biotic (e.g., competition, predation etc.) factors can thus substantially alter any predicted direct plant responses to elevated CO2 (Medlyn et al. 2001; Saxe et al. 1998).

Experiments that try to address the effect of elevated CO2 on soil–plant–atmosphere water-relations are therefore notoriously difficult to conduct and each study system [e.g., free-air-carbon-enrichment (FACE), greenhouse, laboratory and plant growth chamber] has advantages and disadvantages (Ainsworth et al. 2008; Ainsworth and Long 2005; Porter et al. 2015; Poorter et al. 2016). For example, CO2 concentrations in FACE systems have been shown to fluctuate substantially (Pepin and Körner 2002) and are usually shut down at night when the air is too still to ensure constant elevated CO2 treatment, whereas growth chamber environments allow much tighter CO2 control (Poorter et al. 2016) but poorly represent real field conditions. In most FACE studies, elevated CO2 conditions are controlled between 538–680 ppm (Purcell et al. 2018), whereas it is only in growth chamber studies where much tighter CO2 control can be achieved. It has been theoretically demonstrated by Konrad et al. (2008) that small incremental changes in atmospheric CO2 could result in a non-linear gs response to CO2, as opposed to a linear response that is currently assumed in Earth System Models. It is therefore important to not just compare plant responses to large, century changes in CO2 in in situ and ex situ experiments, as currently done in many FACE (Purcell et al. 2018) and chamber experiments, but also to consider investigating gs responses to smaller, decadal changes in CO2 concentration predicted for the next 5–30 years (IPCC 2014).

Measuring the effect of elevated CO2 on plant physiological traits such as gs is of global significance in understanding current, past and future plant responses to a changing climate (Betts et al. 2007; Huntington 2008; McElwain and Steinthorsdottir 2017; Chung et al. 2007; Gornish and Tylianakis 2013). However, collecting data on gs across a wide variety of taxonomic groups, biomes and treatments is often hampered by costs and time constraints. Commercially available systems such as hand-held porometers and portable infrared gas analyzers (IRGA) are amongst the most commonly used devices to measure gs. However, the different approaches to gas exchange measurement make them suitable for different purposes. Leaf porometers measure gs by placing the conductance of a leaf in series with two known conductance elements, and comparing the humidity measurements between them to estimate water vapor flux. Usually a leaf measurement takes 30 s during which an algorithm can predict the final gs reading that would be achieved if unlimited time were allowed for true steady state conditions to occur (Decagon-Devices 2005). In the case of gas analyzers, a reference air mixture is continuously passed through the leaf chamber. Measurements of gs are based on differences in H2O in the air streams that flow into and out of the leaf cuvette. In other words, the rate of water loss is used to calculate the rate of gs (PP-Systems 2007). Since both systems are frequently used in physiological sample protocols in natural, semi-controlled and controlled environments (Long et al. 1996; Lüttge et al. 1986; Yiotis et al. 2017; Bakker 1991; Murray et al. 2019), it is imperative that any deviations in the results between these methods are considered; particularly when interpreted in the light of global change biology (Midgley et al. 1997). Surprisingly, little published data are available comparing porometer and gas analyzer systems (Murray et al. 2019) and, to our knowledge, no published comparison exists that has investigated the difference in derived results under controlled growth chamber environments.

Another fundamental issue that plant biologists face when taking measurements of gs is that gs fluctuates diurnally. Under natural conditions, maximum operational gs is often reached in the late morning to early afternoon, with a mid-day depression around noon (Roessler and Monson 1985; Pathre et al. 1998). Konrad et al. (2008) theoretically demonstrated that maximum daily gs can shift by approximately 1 h for every 180 ppm increase in CO2. The practical implications of this can be quite significant, particularly in studies that aim to identify maximum operational gs responses to different experimental treatments such as elevated CO2. Although diurnal measurements have the disadvantage of being more time consuming and are restricted in the sense that they require the use of a gas analyzer, they do provide a better account of whole-physiological diurnal plant responses than porometers.

The aims of this study were to investigate gs responses to simulated decadal increments in CO2 predicted over the next 4 decades (IPCC 2014) and to test how measurements of gs may differ when two alternative sampling methods are employed (infrared gas analyzer [IRGA] vs. leaf porometer). We focused on both the differences between the recorded values using the two methods and the time-shifts of the maximum daily gs value under fluctuating CO2. In addition, to compare and build the relationship between gas analyzer-collected and porometer-collected data, a data set of gs from 47 species measured under natural field conditions was used from Murray et al. (2019) and compared to our chamber measured plants. In all cases stomatal conductance was measured with both sampling devices.

Materials and methods

Controlled-environment experiment

A total of 54 individuals of bare-rooted Sambucus racemosa L. (red elderberry), 54 saplings of Populus tremula L. (common aspen) and 18 saplings of Populus tremuloides Michx. (quaking aspen) were purchased and grown in controlled experiments. It was not possible to source more individuals of P. tremuloides due to very strict importation regulations. These species were chosen as they are each known to occur in more than one global biomes (boreal forest, temperature deciduous forest, temperate grassland/chaparral and temperate rainforest) (Murray et al. 2019) and have also been used in previous CO2 enrichment studies (Bernacchi et al. 2003). All plants were re-potted into 5 L pots using a growing medium comprising 90% Shamrock® Multi-Purpose Compost (Scotts Horticulture Ltd., Co. Kildare, Ireland) and a 10% combination of Perlite Standard 2–5 mm (Sinclair Pro, Cheshire, UK) and 3 g/l Osmocote® Exact Standard 12–14 M slow release fertilizer (15-9-11 + 2MgO + TE; Scotts International BV, Netherlands). The plants were kept for 2 weeks in the open air at Rosemount Environmental Research Station, University College Dublin (UCD), Ireland, before being treated for pests with an emulsifiable concentrate containing 5% pyrethrin (Pyrethrum 5EC at 20 ml/5 L—Agropharm Ltd., UK). The plants were then moved into CONVIRON (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada) BDR-16 and BDW-40 plant growth chambers within the Programme for Experimental Atmospheres and Climate (PÉAC) facility at UCD. The chambers allow monitoring and control of atmospheric conditions including air temperature (T) (°C), relative humidity (RH) (%), light (PAR) (µmol m−2 s−1) and atmospheric [O2] (%) and [CO2] (ppm). For the experiment, chambers were programmed to run a 16.5 h/7.5 h day/night cycle. Maximum day time T and RH were set to 22 °C and 70%, respectively. Maximum night time T and RH were set to 15 °C and 60%, respectively. Light intensity was set to reach a maximum of 600 μmol m−2 s−1 at noon (Table 1) and O2 concentration was set to ambient concentration of 20.9% in all chambers. A ramping program was used to ensure a uniform diurnal increase in T, RH and light conditions. CO2 concentrations were set to 350, 420, 490 and 560 ppm in two chambers per CO2 treatment (8 chambers in total) and were monitored in each chamber with a PP-Systems WMA-4 CO2 gas analyzer. The CO2 concentrations represented the year 1987, 2025, 2051 and 2070, respectively, according to the low-medium stabilization RCP4.5 scenario (IPCC 2014). Supplementary CO2 for all the chambers was provided by a compressed gas tank containing liquid CO2. Since two different chamber types were used in the experiment, an additional control chamber (BDW-40) was added to the 420 ppm treatment to identify any potential confounding effects that might have occurred due to differences in chamber type (Porter et al. 2015). To attain sub-ambient (350 ppm) CO2 in the chambers, an inline fan with a variable damper regulated the amount of air that was passed from the chambers through an external soda lime unit (2–5 mm Sofnolime™—Molecular Products Group Ltd., Essex, UK). The CO2 free air was then passed back into the chambers and CO2 was injected to reach the target sub-ambient set point conditions. All measured chamber conditions are reported in Table 1.

To acclimatize plants to chamber conditions, six plants of P. tremula and S. racemosa and two plants of P. tremuloides were transferred into each chamber (Table 2) and grown under ambient local conditions (420 ppm CO2 and 21% O2) for 14 days before treatment conditions were initiated. The plants were then grown for 126 days under treatment. Plants were watered and fertilized (N:P:K; 22:4:22) every 2 days and 2 weeks, respectively. Soil moisture content was monitored using a Delta-T Devices HH2 Moisture Meter (Delta-T Devices Ltd., Cambridge, UK) (P. tremula = 0.25 ± 0.12 m3·m−3; P. tremuloides = 0.29 ± 0.11 m3·m−3; S. racemosa = 0.25 ± 0.13 m3·m−3). Plants were rotated randomly twice within each chamber to avoid spatial acclimation (Hammer and Hopper 1997) or within-chamber variability (Porter et al. 2015).

Stomatal conductance was measured using a PP-Systems Ciras-2 infrared gas analyzer attached to a PLC6(U) Automatic Universal Leaf Cuvette and a hand-held Decagon Devices SC-1 Leaf Porometer. Measurements were taken inside the chambers on a minimum of two, fully expanded leaves per individual plant that had developed fully under treatment conditions. Each leaf was labelled and measured repeatedly throughout the experiment. The IRGA was used to measure gs over 24 h for each species in all treatments (n = 10), except the 490 ppm treatment as we were restricted by the availability of equipment. The light emitting diode (LED) unit was removed from the leaf cuvette to attain ambient light conditions in the cuvette (see supplementary figure). Leaves were allowed to equilibrate within the cuvette for a minimum of 20 min. until gs had remained stable for approximately 15 min. at a VPD of 1 kPa. CO2 concentrations in the leaf cuvette were fixed to the ambient treatment condition of each of the growth chambers (Table 1). Leaf temperature was determined using the energy balance setting. To avoid temporal differences between measurements, plants were measured in rotation across treatments. In combination with the 24 h measurements, a leaf porometer was used to make additional spot measurements at 11 am in the morning on two leaves per individual plant over several days. To ensure plants were measured at the same time of the day, the time setting of the plant growth chambers was staggered by 1 hour.

Field data

See Murray et al. (2019) for a detailed account of the field data collection protocol. Briefly, gs measurements were carried out in North and Central America in the summer of 2014. A total of 47 C3 woody angiosperm tree and shrub species were sampled in two boreal forest sites (Bird Creek [60°58′ N, 149°28′ W] and Kenai [60°33.3′ N, 151°12.8′ W], Alaska, USA), one temperate deciduous forest site (Smithsonian Environmental Research Centre [38°53′ N, 76°32′ W], Maryland, USA), two tropical seasonal forest (wet) sites (Cambalache [18°27′ N, 66°35′ W] and Guajataca [18°24′ N, 66°58′ W], Puerto Rico) and one tropical seasonal forest (dry) site (Guanica [17°93′ N, 66°92′ W], Puerto Rico). Stomatal conductance was measured with a CIRAS-2 gas analyzer (PP-Systems, Amesbury, MA, USA) attached to a PLC6(U) cuvette fitted with a 1.7 cm2 measurement window and a red/white light LED unit. Stomatal conductance was measured at ambient atmospheric CO2 of 400 ppm on an average of four individuals per species between 9:00 am and 13:00 pm on a sun exposed leaf following standard sample protocols (Berveiller et al. 2007; Domingues et al. 2010; Koch et al. 2004; Rowland et al. 2015; Dang et al. 1997). Cuvette conditions were set at 200 cm3 min−1 air flow, 1000 μmol m−2 s−1 light intensity and 80–90% incoming mole fraction of water vapor. To standardize our measurement protocol for each site, regardless of the temperature changes during the daily measurement time window, they calculated the average site-specific leaf temperature at 9:00 am by recording the leaf temperature of at least ten leaves belonging to ten different species grown at each site. For the final gs measurements each leaf was left to equilibrate for at least 15 min before values were recorded.

In addition to the IRGA gs measurements, a Decagon Devices SC-1 steady state Leaf Porometer was used to measure gs on the same species and site, on fully exposed leaves (Murray et al. 2019). One leaf on three individuals per species was measured consecutively over 4 days. As with the IRGA, measurements were not taken on wet days or on wet leaves. Where moisture was a factor, excess moisture was blotted off and the leaf was left to dry before it was measured (Murray et al. 2019).

Analysis

Data were tested for normality and equal variance. Difference in gs between treatments was tested separately for each species using ANOVA comparison. The ANOVA was weighted by the soil moisture content of each plant to account for variability in soil moisture between gs measurements. ANOVA comparisons that were significant were further analyzed using pairwise tests with Bonferroni corrections. To identify how maximum diurnal gs shifted between treatments, a polynomial surface was fitted using non-parametric locally weighted regression. Maximum gs was then calculated for each fit (species and treatment) separately. To test for chamber effects as a result of using different chamber types, mixed effect models were used. All analysis was performed using the statistical package ‘R’ version 3.4 (R Developing Core Team 2017).

Results

In the chambers, diurnal physiological responses of photosynthetic assimilation (A) (µmol m−2 s−1), gs (mmol m−2 s−1), transpiration (mmol m−2 s−1) and iWUE (= A/gs) (µmol m−2 s−1)/(mmol m−2 s−1) contrasted between and within species grown at different CO2 concentrations (Fig. 1). Assimilation was lowest at the 350 ppm treatment for P. tremula and higher at the 420 and 560 ppm treatments (Fig. 1a); iWUE was therefore greatest for individuals grown under 560 ppm conditions (Fig. 1d). Assimilation and iWUE for P. tremuloides showed the opposite response with higher A and iWUE under 350 ppm CO2 conditions. Although A and iWUE were also higher for S. racemosa in the 350 ppm CO2 treatment, the differences between treatments were much smaller (Fig. 1a, d).

Diurnal physiological responses of plants grown under 350 (circle and red), 420 (triangle and green) and 560 ppm (square and blue) CO2. No IRGA data for the 490 ppm treatment was collected due to restricted access to equipment. a assimilation (A), b stomatal conductance (gs), c transpiration and d intrinsic water use efficiency (iWUE). Each value is the mean of approximately ten measurements per treatment (n = 10). Vertical bars represent the 95% confidence interval

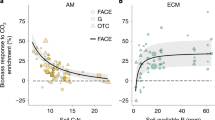

Generally, gs and transpiration decreased under elevated CO2 (Fig. 1b, c) for all three species, with the greatest difference observed between the 350 ppm and 560 ppm CO2 treatments. The decrease in gs under elevated CO2 was best explained by a log regression (overall F = 6.825, r2 = 0.689, p = 0.03), showing that the mean gs response to CO2 when measured at 11 am was non-linear for all three species in the IRGA measurements (Fig. 2). This non-linear decrease was also reflected for two species (P. tremula and P. tremuloides) in the porometer measurements (Fig. 3).

Fitted species and mean (black solid line) log regression (F = 6.825, r2 = 0.69, p = 0.03) of gs across CO2 treatments. Grey-shaded area represents the standard error for the mean fit of all three species. Individual measurements represent the mean and 95% confidence intervals of daytime gs measured using a PP Systems CIRAS-2 (n = 10)

Stomatal conductance measured with a porometer (dashed lines) and an IRGA (solid lines) for each species (different colors) and within each CO2 (ppm) treatment. The means and 95% confidence intervals are shown. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (Bonferroni post-hoc test at p < 0.05). The spot measurements were taken between 11 am and noon every second day. Each value is the mean of approximately 160 (porometer) and 10 (IRGA) repeated measurements per treatment

The time of the maximum operational gs also differed between treatments and was species-specific (Fig. 4b). For S. racemosa, the maximum operational gs shifted across the day by 1–2 h for each 70 ppm increase in CO2. For P. tremuloides, maximum operational gs shifted across the day by 1–2 h from 350 to 420 ppm CO2 but no shift was observed between 420 and 560 ppm CO2. There was a shift in maximum gs to earlier hours for P. tremula in response to changes in CO2 concentrations (Fig. 4b).

The comparison of measured gs between the porometer and IRGA in the growth chambers showed that, in general, the measured gs responses under elevated CO2 were proportionally very similar. Both methods detected a decrease in gs with elevated CO2. However, the magnitude of measured gs responses varied between the porometer and CIRAS, with an average of ~ 25% higher values in gs observed when the porometer was used (Fig. 3). Although no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) was observed between the three treatments, the relative difference in measured gs between the porometer and the IRGA increased with elevated CO2 (~ 20–30%).

Following the work of Murray et al. (2019), there was a strong positive correlation between the IRGA and the porometer measured gs of our 47 measured species in the field (Fig. 5; F = 64.05, r2 = 0.58, p < 0.01). Figure 5 also suggests that low conducting species display greater proportional difference between IRGA and porometer observations due to the fact that the relationship crosses the y axis at a value of 30 mmol m−2 s−1 (F = 7.29, r2 = 0.12, p < 0.01). The mean differences in measured gs between the IRGA and the porometer for P. tremuloides and S. racemosa measured in the field in woody C3 angiosperm taxa was 24.3% and 40.6%, respectively. This was of a similar magnitude compared to the difference of gs between the IRGA and the porometer for P. tremuloides (17%) and S. racemosa (31%) measured in the growth chambers at 420 ppm (Fig. 5).

Comparison of mean porometer and IRGA measured gs in field and chamber conditions. The black dots show the porometer and IRGA comparison of 45 species in the field by Murray et al. (2019). The green symbols show the same comparison in the field for P. tremuloides (upside down triangle) and S. racemosa (upright triangle). The red symbols show the porometer and IRGA comparison in the chambers for P. tremuloides (square) and S. racemosa (diamond). Note that the field measurements were done under 400 ppm, whereas the chamber measurements for this comparison was done with individuals in the 420 ppm treatment. The y-intercept was fixed to 30 mmol m−2 s−1. This was done because preliminary measurements using dry pieces of paper and plastic revealed that porometer measurements were on average 30 mmol m−2 s−1 higher from zero compared to IRGA measurements (gs = 0) [see Murray et al. (2019) for more detail]

Discussion

The non-linearity of gs response to increasing CO2 has been predicted in empirical explorations and modelling studies (Konrad et al. 2008; Maherali et al. 2002; Gill et al. 2002; Medlyn et al. 2011; de Boer et al. 2011). However, in many published studies plants are often exposed to large step increases in CO2, mostly comparing ambient to high (~ 600 ppm) CO2 manipulations; representing centurial increase in CO2 (Ainsworth et al. 2008; Ainsworth and Long 2005). Since atmospheric CO2 is expected to increase gradually in the future, large step increases from CO2 studies are not easily extrapolated to intermediate CO2 concentration increases; hence why in some studies a non-linear response has often gone undetected (Long et al. 2004). The non-linear decrease in gs can only be detected when plants are exposed to decadal rather than centurial magnitude CO2 change. Growth chamber experiments compared to other experimental systems (e.g., FACE) have a technical advantage when it comes to subtle (e.g., decadal) manipulations of the CO2 environment, as they can control CO2 more tightly (increments of + 50 to + 70 ppm are possible, see Table 1). We found clear evidence that at least two of the species measured in this experiment are responding to elevated CO2 with a non-linear decrease in gs. Understanding and demonstrating this non-linear decrease through experimental manipulation can help to refine predictions to ecosystem responses (Bonan et al. 2014).

The decrease in gs under elevated CO2 was in some cases accompanied by an increase in A and iWUE (Fig. 1). The adjustment of gs to CO2, via feedback regulation of stomatal aperture and or stomatal density and pore size, is part of the mechanism for optimizing CO2 uptake with respect to water loss (Haworth et al. 2013). The decrease of A in P. tremuloides under elevated CO2 can possibly be attributed to a strong down-regulation of photosynthesis (Ainsworth and Long 2005) or increased stomatal limitation (e.g., speed or stomatal anatomy) compared to the two other species. The latter is less likely to be the case, as gs in P. tremuloides at 420 and 560 ppm are equal or higher compared to the gs values of the other two species. In S. racemose, where A did not change and gs was generally lower compared to the other species, the possible increased stomatal limitation at elevated CO2 had potentially a greater impact on A values. When plotting A against gs for each species, the species that had the strongest control/limitation of gs on A was P. tremuloides, followed by P. tremula and S. racemosa (not shown). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that long-term exposure to CO2 in C3 plants can, in some instances, result in a reduction or even complete suppressing of A (Makino and Mae 1999; Faria et al. 1996). Such responses have been attributed to secondary responses related to decreased nitrogen content or excess carbohydrate accumulation in the leaves, and has often been documented in drought conditions (Cregger et al. 2014; Griffin et al. 2004). Drought is less likely to be the cause of the responses observed here, as the soil moisture was monitored when gs measurements were taken throughout the experiment and did not change between treatments (p > 0.05) or throughout the duration of the experiment. Also, sink limitations as a result of pot experiments are a likely cause of the observed down regulation of A in S. racemosa under elevated CO2 (Ruiz-Vera et al. 2017; Schaz et al. 2014). All plants were provided with liquid fertilizer and were potted in soil that contained slow release fertilizer. However, no soil characteristics (e.g., nitrogen, pH) were measured to exclude this possibility. S. racemosa grew much faster compared to the two other species (pers. obs.), which could have resulted in less optimal growing conditions, as the fertilizer input was not changed throughout the duration of the experiment.

Our data demonstrated that the porometer generally over-estimates gs in growth chamber conditions (Fig. 3), and this is independently confirmed in field measurements of the same taxa and other woody angiosperms (Fig. 5). Similar to our findings, Ramírez et al. (2006) demonstrated that porometer measurements over-estimated gs by approximately 32% compared to IRGA measurements in Stipa tenacissima L. The over-estimation of gs values using the porometer is ~ 25% on average and is more pronounced in species with low gs and under conditions that lead to decreased gs (e.g., elevated CO2—Fig. 5). Yet, this difference was not statistically significant. The CO2 effect on the relative gs difference is likely the result of a stomatal closing response when CO2 is increased, thus decreasing gs and increasing the difference in measured gs between the IRGA and the porometer. In addition, the relative differences in gs are the result of the differences in how gs is measured between the devices. The IRGA system allows more time for the leaf-chamber conditions to equilibrate before the measurement is taken (usually within 15 min.), whereas it only takes a few seconds for equilibrium to occur in the porometer chamber. Steady-state porometers are used frequently in plant studies (Jones 1999; Grant et al. 2007; Maes et al. 2016; Keel et al. 2006; Nijs et al. 1997), making the findings presented here relevant to many eco-physiologists, who rely on the accuracy of these devices. Using the proposed relationship adjustment by Murray et al. (2019) to account for this observed difference would help future comparative studies that would like to make use of measurements from both porometer and IRGA studies.

The porometer can be temporally limiting as it only provides an instantaneous measurement of gs at a given time, whereas the IRGA can provide multiple gs measurements over a longer time scale (up to 28 h depending on settings). When the measured species display large fluctuations in gs across the diurnal cycle, this becomes important, as porometer protocols, which usually involve a single spot measurement per day, are less likely to capture this variability. For example, the diurnal shift in maximum gs with elevated CO2 was previously suggested by Konrad et al. (2008) using an optimization model. He showed that under given environmental conditions, maximum gs happens between 7.00 and 10.00 am for CO2 values < 700 ppm, but that gs shifted to 10.00–13.00 for atmospheric CO2 values > 700 ppm. Similarly, we demonstrated that for P. tremuloides and S. racemosa, maximum gs shifted into the afternoon as a result of elevated CO2 (Fig. 4). Short-term changes in stomatal aperture are often caused by diurnal variations of temperature, insolation, atmospheric humidity, light and wind speed (Konrad et al. 2008). ‘Long-term’ exposure in atmospheric CO2 on the other hand, has shown to affect stomatal anatomy and thus maximum theoretical conductance (gmax) (Franks and Beerling 2009). The species-specific difference in maximum gs to an increase in CO2 observed here, is likely to be a response of anatomical stomatal changes (e.g., density and size). For example, an increase in CO2 is often associated with a decrease in stomatal density and an increase in stomatal size (Franks and Beerling 2009). Although we did not measure anatomical traits here, Konrad et al. (2008) showed that the timing of maximum gs is strongly dependent on the environmental conditions, stomatal traits and the rate of assimilation. It is likely that our species did adjust their gmax and thus optimized their timings of physiological responses to elevated CO2.

Changes of the time of the day when water is lost by plants could potentially influence the timing of precipitation in some biomes by altering plant-atmospheric dynamics, particularly in biomes where evaporation makes up a large proportion of the evapotranspiration flux (Schlesinger and Jasechko 2014). In addition, the shift in gs with elevated CO2 has important consequences for the way gs is measured in studies that are interested in the effect of elevated CO2 on gs. In particular it is critical to know the diurnal gs pattern of the species to be studied, if the aim of the research is to measure maximum gs. For example, our species do not show a very strong mid-day depression, which has been observed in other taxa (Pathre et al. 1998; Franco and Lüttge 2002; Tucci et al. 2010; Kosugi and Matsuo 2006). As previously mentioned, the absolute gs value may be overestimated, but more importantly the optimal time (i.e. gs is at its maximum) when measurements are taken between the ambient and high CO2 treatments will differ as a result. For example, we found that an increase of 70 ppm CO2 in S. racemosa shifted the maximum gs into the afternoon by approximately 1–2 h. This response can be very species-specific (Fig. 4) and is also likely to depend on the model fitted. An experiment that aims to identify how maximum gs differs between CO2 treatments, using a sample protocol with fixed time-points across all treatments, is likely not to capture the actual maximum gs in a day as a result of such a shift. It would therefore be advisable to combine porometry with 24 h response measurements from an IRGA to ensure that the measuring times between treatments are adjusted. However, it remains to be seen whether our findings are applicable across different environmental conditions and taxonomic groups.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that the species in this study respond non-linearly to increases in CO2 concentration when exposed to decadal changes in CO2; small CO2 concentrations increases (70 ppm) often not tested by other studies. In addition, we showed that the daily maximum gs can, in some species, shift later into the day when plants are exposed to only 70 ppm increases in CO2. Our findings have potential important implications to the diurnal water and carbon budget of plants, and the feedback of these across the soil–plant–atmospheric continuum; specifically under future changes in atmospheric CO2. Due to the importance of stomata regulating global water fluxes, CO2 effects that result in gs (a) decreasing non-linearly and (b) possibly shifting diurnally, need to be considered, as shown here and elsewhere, when attempting to refine predictions of plant responses to CO2 across ecosystems.

Author contribution statement

SB and JM conceived and designed the research. SB, CY and CE-K conducted the experiment. SB and CY analyzed the data. SB wrote the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

References

Ainsworth EA, Leakey ADB, Ort DR, Long SP (2008) FACE-ing the facts: inconsistencies and interdependence among field, chamber and modeling studies of elevated [CO2] impacts on crop yield and food supply. New Phytol 179(1):5–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02500.x

Ainsworth EA, Long SP (2005) What have we learned from 15 years of free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE) A meta-analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy properties and plant production to rising CO2. New Phytol 165(2):351–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01224.x

Ainsworth EA, Rogers A (2007) The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising CO2: mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant Cell Environ 30(3):258–270

Bakker JC (1991) Leaf conductance of four glasshouse vegetable crops as affected by air humidity. Agric For Meteorol 55(1):23–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1923(91)90020-Q

Bernacchi CJ, Calfapietra C, Davey PA, Wittig VE, Scarascia-Mugnozza GE, Raines CA, Long SP (2003) Photosynthesis and stomatal conductance responses of poplars to free-air CO2 enrichment (PopFACE) during the first growth cycle and immediately following coppice. New Phytol 159(3):609–621. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00850.x

Berveiller D, Kierzkowski D, Damesin C (2007) Interspecific variability of stem photosynthesis among tree species. Tree Physiol 27(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/27.1.53

Betts RA, Boucher O, Collins M, Cox PM, Falloon PD, Gedney N, Hemming DL, Huntingford C, Jones CD, Sexton DMH, Webb MJ (2007) Projected increase in continental runoff due to plant responses to increasing carbon dioxide. Nature 448(7157):1037–1041. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06045

Bonan GB, Williams M, Fisher RA, Oleson KW (2014) Modeling stomatal conductance in the earth system: linking leaf water-use efficiency and water transport along the soil–plant–atmosphere continuum. Geosci Model Dev 7(5):2193–2222. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-7-2193-2014

Brodribb TJ, McAdam SAM (2017) Evolution of the stomatal regulation of plant water content. Plant Physiol 174(2):639–649. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.00078

Chung H, Zak DR, Reich PB, Ellsworth DS (2007) Plant species richness, elevated CO2, and atmospheric nitrogen deposition alter soil microbial community composition and function. Global Change Biol 13(5):980–989. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01313.x

Cregger MA, McDowell NG, Pangle RE, Pockman WT, Classen AT (2014) The impact of precipitation change on nitrogen cycling in a semi-arid ecosystem. Funct Ecol 28(6):1534–1544. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12282

Curtis PS, Wang X (1998) A meta-analysis of elevated CO2 effects on woody plant mass, form, and physiology. Oecologia 113(3):299–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420050381

Dang Q-L, Margolis HA, Coyea MR, Sy M, Collatz GJ (1997) Regulation of branch-level gas exchange of boreal trees: roles of shoot water potential and vapor pressure difference. Tree Physiol 17(8–9):521–535. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/17.8-9.521

de Boer HJ, Lammertsma EI, Wagner-Cremer F, Dilcher DL, Wassen MJ, Dekker SC (2011) Climate forcing due to optimization of maximal leaf conductance in subtropical vegetation under rising CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108(10):4041–4046. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100555108

Devices D (2005) Leaf porometer—operator’s manual, 9th edn. Pullman, USA

Domingues TF, Meir P, Feldpausch TR, Saiz G, Veenendaal EM, Schrodt F, Bird M, Djagbletey G, Hien F, Compaore H, Diallo A, Grace J, Lloyd JON (2010) Co-limitation of photosynthetic capacity by nitrogen and phosphorus in West Africa woodlands. Plant Cell Environ 33(6):959–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02119.x

Faria T, Wilkins D, Besford RT, Vaz M, Pereira JS, Chaves MM (1996) Growth at elevated CO2 leads to down-regulation of photosynthesis and altered response to high temperature in Quercus suber L. seedlings. J Exp Bot 47 (11):1755–1761. 10.1093/jxb/47.11.1755

Franco A, Lüttge U (2002) Midday depression in savanna trees: coordinated adjustments in photochemical efficiency, photorespiration, CO2 assimilation and water use efficiency. Oecologia 131(3):356–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-002-0903-y

Franks PJ, Beerling DJ (2009) Maximum leaf conductance driven by CO2 effects on stomatal size and density over geologic time. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106(25):10343–10347. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0904209106

Gill RA, Polley HW, Johnson HB, Anderson LJ, Maherali H, Jackson RB (2002) Nonlinear grassland responses to past and future atmospheric CO2. Nature 417(6886):279–282

Gornish ES, Tylianakis JM (2013) Community shifts under climate change: mechanisms at multiple scales. Am J Bot 100(7):1422–1434. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1300046

Grant OM, Tronina Ł, Jones HG, Chaves MM (2007) Exploring thermal imaging variables for the detection of stress responses in grapevine under different irrigation regimes. J Exp Bot 58(4):815–825. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erl153

Griffin JJ, Ranney TG, Pharr DM (2004) Heat and drought influence photosynthesis, water relations, and soluble carbohydrates of two ecotypes of redbud (Cercis canadensis). J Am Soc Hort Sci 129 (4):497–502. 10.21273/JASHS.129.4.0497

Hammer PA, Hopper DA (1997) Experimental design. In: Langhans RW, Tibbitts TW (eds) Plant growth chamber handbook. Iowa State University, Ames, pp 177–187

Haworth M, Elliott-Kingston C, McElwain J (2013) Co-ordination of physiological and morphological responses of stomata to elevated [CO2] in vascular plants. Oecologia 171(1):71–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-012-2406-9

Huntington TG (2008) CO2-induced suppression of transpiration cannot explain increasing runoff. HyPr 22(2):311–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.6925

IPCC (2014) Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: global and sectoral aspects. contribution of working group II to the Fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change In: Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Jasechko S, Sharp ZD, Gibson JJ, Birks SJ, Yi Y, Fawcett PJ (2013) Terrestrial water fluxes dominated by transpiration. Nature 496(7445):347–350. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11983

Jones HG (1999) Use of thermography for quantitative studies of spatial and temporal variation of stomatal conductance over leaf surfaces. Plant Cell Environ 22(9):1043–1055. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00468.x

Keel SG, Pepin S, Leuzinger S, Körner C (2006) Stomatal conductance in mature deciduous forest trees exposed to elevated CO2. Trees 21(2):151–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-006-0106-y

Koch GW, Sillett SC, Jennings GM, Davis SD (2004) The limits to tree height. Nature 428:851–854. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02417

Konrad W, Roth-Nebelsick A, Grein M (2008) Modelling of stomatal density response to atmospheric CO2. J Theor Biol 253(4):638–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.03.032

Kosugi Y, Matsuo N (2006) Seasonal fluctuations and temperature dependence of leaf gas exchange parameters of co-occurring evergreen and deciduous trees in a temperate broad-leaved forest. Tree Physiol 26(9):1173–1184

Lammertsma EI, Boer HJd, Dekker SC, Dilcher DL, Lotter AF, Wagner-Cremer F (2011) Global CO2 rise leads to reduced maximum stomatal conductance in Florida vegetation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108(10):4035–4040. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100371108

Long SP, Ainsworth EA, Rogers A, Ort DR (2004) Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide: plants FACE the future. Annu Rev Plant Biol 55:591–628. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141610

Long SP, Farage PK, Garcia RL (1996) Measurement of leaf and canopy photosynthetic CO2 exchange in the field1. J Exp Bot 47(11):1629–1642. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/47.11.1629

Lüttge U, Stimmel KH, Smith JAC, Griffiths H (1986) Comparative ecophysiology of CAM and C3 bromeliads. II. Field measurements of gas exchange of CAM bromeliads in the humid tropics. Plant Cell Environ 9 (5):377–383. 10.1111/j.1365–3040.1986.tb01751.x

Maes WH, Baert A, Huete AR, Minchin PEH, Snelgar WP, Steppe K (2016) A new wet reference target method for continuous infrared thermography of vegetations. Agric For Meteorol 226:119–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2016.05.021

Maherali H, Reid CD, Polley HW, Johnson HB, Jackson RB (2002) Stomatal acclimation over a subambient to elevated CO2 gradient in a C3/C4 grassland. Plant Cell Environ 25(4):557–566. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00832.x

Makino A, Mae T (1999) Photosynthesis and plant growth at elevated levels of CO2. Plant Cell Physiol 40(10):999–1006. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029493

McElwain J, Steinthorsdottir M (2017) Palaeoecology, ploidy, palaeoatmospheres and developmental biology: a review of fossil stomata. Plant Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.00204

Medlyn BE, Barton CVM, Broadmeadow MSJ, Ceulemans R, De Angelis P, Forstreuter M, Freeman M, Jackson SB, Kellomäki S, Laitat E, Rey A, Roberntz P, Sigurdsson BD, Strassemeyer J, Wang K, Curtis PS, Jarvis PG (2001) Stomatal conductance of forest species after long-term exposure to elevated CO2 concentration: a synthesis. New Phytol 149(2):247–264. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00028.x

Medlyn BE, Duursma RA, Eamus D, Ellsworth DS, Prentice IC, Barton CVM, Crous KY, De Angelis P, Freeman M, Wingate L (2011) Reconciling the optimal and empirical approaches to modelling stomatal conductance. Global Change Biol 17(6):2134–2144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02375.x

Midgley GF, Veste M, don Willert DJ, Davis GW, Steinberg M, Powrie LW (1997) Comparative field performance of three different gas exchange systems, vol 27.

Murray M, Soh WK, Yiotis C, Batke S, Parnell AC, Spicer RA, Lawson T, Caballero R, Wright IJ, Purcell C, McElwain JC (2019) Convergence in maximum stomatal conductance of c3 woody angiosperms in natural ecosystems across bioclimatic zones. Frontiers in Plant Science 10 (558). 10.3389/fpls.2019.00558

Nijs I, Ferris R, Blum H, Hendrey G, Impens I (1997) Stomatal regulation in a changing climate: a field study using Free Air Temperature Increase (FATI) and Free Air CO2 Enrichment (FACE). Plant Cell Environ 20(8):1041–1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.1997.tb00680.x

Pathre U, Sinha AK, Shirke PA, Sane PV (1998) Factors determining the midday depression of photosynthesis in trees under monsoon climate. Trees 12(8):472–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004680050177

Pepin S, Körner C (2002) Web-FACE: a new canopy free-air CO2 enrichment system for tall trees in mature forests. Oecologia 133(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-002-1008-3

Poorter H, Fiorani F, Pieruschka R, Wojciechowski T, van der Putten WH, Kleyer M, Schurr U, Postma J (2016) Pampered inside, pestered outside? Differences and similarities between plants growing in controlled conditions and in the field. New Phytol 212(4):838–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14243

Porter AS, Gerald CE, McElwain JC, Yiotis C, Elliott-Kingston C (2015) How well do you know your growth chambers? Testing for chamber effect using plant traits. Plant Methods 11:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13007-015-0088-0

PP-Systems (2007) TPS-2 portable photosynthesis system. 2.01 edn., Hitchin, UK

Purcell C, Batke SP, Yiotis C, Caballero R, Soh WK, Murray M, McElwain JC (2018) Increasing stomatal conductance in response to rising atmospheric CO2. Ann Bot pp mcx208-mcx208. 10.1093/aob/mcx208

R Developing Core Team (2017) R: a language and environment for statistical computing 3.1.2 edn. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

Ramírez DA, Valladares F, Blasco A, Bellot J (2006) Assessing transpiration in the tussock grass Stipa tenacissima L.: the crucial role of the interplay between morphology and physiology. Acta Oecol 30 (3):386–398. 10.1016/j.actao.2006.06.006

Roessler PG, Monson RK (1985) Midday depression in net photosynthesis and stomatal conductance in yucca glauca. relative contributions of leaf temperature and leaf-to-air water vapor concentration difference. Oecologia 67 (3):380–387. 10.1007/BF00384944

Rowland L, Lobo-do-Vale RL, Christoffersen BO, Melém EA, Kruijt B, Vasconcelos SS, Domingues T, Binks OJ, Oliveira AAR, Metcalfe D, da Costa ACL, Mencuccini M, Meir P (2015) After more than a decade of soil moisture deficit, tropical rainforest trees maintain photosynthetic capacity, despite increased leaf respiration. Global Change Biol 21(12):4662–4672. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13035

Ruiz-Vera UM, De Souza AP, Long SP, Ort DR (2017) The Role of Sink Strength and Nitrogen Availability in the Down-Regulation of Photosynthetic Capacity in Field-Grown Nicotiana tabacum L. at elevated CO(2) concentration. Frontiers in Plant Science 8:998. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00998

Saxe H, Ellsworth DS, Heath J (1998) Tree and forest functioning in an enriched CO2 atmosphere. New Phytol 139(3):395–436. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.1998.00221.x

Schaz U, Düll B, Reinbothe C, Beck E (2014) Influence of root-bed size on the response of tobacco to elevated CO(2) as mediated by cytokinins. AoB Plants 6:plu010. 10.1093/aobpla/plu010

Schlesinger W, Jasechko S (2014) Transpiration in the global water cycle. Agri and Forest Meteor 189–190:115–117

Stitt M, Krapp A (1999) The interaction between elevated carbon dioxide and nitrogen nutrition: the physiological and molecular background. Plant Cell Environ 22(6):583–621. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00386.x

Tucci M, Erismann N, Machado E, Ribeiro R (2010) Diurnal and seasonal variation in photosynthesis of peach palms grown under subtropical conditions. Photosynthetica 48(3):421–429

Woodward FI (1987) Stomatal numbers are sensitive to increases in CO2 from pre-industrial levels. Nature 327(6123):617–618. https://doi.org/10.1038/327617a0

Woodward FI, Kelly CK (1995) The influence of CO2 concentration on stomatal density. New Phytol 131(3):311–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1995.tb03067.x

Xu Z, Jiang Y, Jia B, Zhou G (2016) Elevated-CO(2) response of stomata and its dependence on environmental factors. Front Plant Sci 7:657. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.00657

Yiotis C, Gerald CE, McElwain JC (2017) Differences in the photosynthetic plasticity of ferns and Ginkgo grown in experimentally controlled low [O2]:[CO2] atmospheres may explain their contrasting ecological fate across the Triassic-Jurassic mass extinction boundary. Ann Bot 119(8):1385–1395. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcx018

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Aidan Holohan, Dr. Amanda Porter and Dr. Christiana Evans-Fitzgerald for their useful discussions. We also thank technical staff and students at University College Dublin including Ms. Bredagh Moran, Mr. Gordon Kavanagh and Mr. Conor Copeland. This study was supported by a Science Foundation Ireland PI Grant 11/PI/1103 and two Irish Research Council Fellowship grants (GOIPD/2016/261 and GOIPD/2016/320).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

425_2020_3343_MOESM1_ESM.tiff

Diurnal light condition measured with the IRGA of plants grown under 350 (circle and red), 420 (triangle and green) and 560 ppm (square and blue) CO2. No IRGA data for the 490 ppm treatment was collected due to access restriction to equipment. Each value is the mean of approximately ten measurements per treatment (n = 10). Vertical bars represent the 95% confidence interval (TIFF 1187 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Batke, S.P., Yiotis, C., Elliott-Kingston, C. et al. Plant responses to decadal scale increments in atmospheric CO2 concentration: comparing two stomatal conductance sampling methods. Planta 251, 52 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-020-03343-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-020-03343-z