Abstract

Background

Most individuals spend a significant amount of their time at work, and the dynamics at work can potentially influence their overall life, especially health and mental health. The present study tried to understand the association of the nature of work categorized as physically demanding, psychologically demanding, and environmentally hazardous on life satisfaction, cognitive functioning, and depressive symptoms among working middle-aged and older adults in India.

Method

We used data from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI), Wave 1, collected between 2017 and 2018. The study sample consists of 28,653 working adults aged between 45 and 70. The study measures were assessed using standard tools. Linear regression analysis was employed.

Results

The results indicate that individuals working in less physically demanding (β = 0.06, 99% CI = 0.02–0.09) and not hazardous environments (β = 0.15, 99% CI = 0.09–0.20) had better life satisfaction. Also, not being involved in hazardous work environments increased the likelihood of good cognitive functioning and reduced depressive symptoms (β= -0.17, 99% CI= -0.20- -0.15). However, samples involved in works requiring less psychological demand had an increased likelihood of reduced life satisfaction and increased depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

This study’s results highlight the importance of creating a conducive working environment for the ageing adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Most individuals spend a significant amount of their time at work, and the dynamics at work have considerable potential to influence their overall lives. Throughout the period, the nature of work became more refined and specific to specialized areas that met the requirements of the particular period (Shinohara 2016). Also, with demographic changes and technological advancements, there have been notable changes in the job requirements and nature of work from the past (Scully-Russ and Torraco 2020). The work that began as the requirement for financial fulfillment is a double-edged sword as it acts as a resource and a threat to physical and psychological health (Sinclair et al. 2020). The literature suggests unemployed individuals had poor mental health profiles, lower health-seeking behavior and behavioral health problems (Pharr et al. 2011), and also greater vulnerabilities to mental health issues compared to their counterparts (Ahn et al. 2021). Although employment acted as a protective factor from ill effects, surprisingly, it also takes a toll on mental health, as a range of factors associated with work nature and labor interfered with it. Currently, the cases of mental health problems are higher among employed individuals than the unemployed (Oliveros et al. 2022).

Various dynamics of work interfere with well-being. One such is job quality, which includes the physical environment, labor intensity, working hours, social environment, skills, autonomy, and income ( Kim et al. 2023), which could influence life satisfaction. In addition, studies suggested the significant impact of work conditions, occupational safety, and unpredictable work schedules on physical and mental health (Theorell et al. 2015; Hanvold et al. 2019; Lee and Kawachi 2021; Ronchetti et al. 2021). Conversely, subjective well-being is important for positive job performance and productivity, as proposed by the happy-productive thesis (Wright et al. 2007; Zelenski et al. 2008). Further, this points to the interdependent nature between work features and psychological well-being (De Lange et al., 2004).

In this line, a study among Malaysian working women evidenced that the level of satisfaction with the nature of work was a significant predictor of psychological distress, sleep disturbances, and problematic health outcomes (Aazami et al. 2015). Similarly, high-risk jobs were related to a range of psychiatric conditions, including neurotic depression, phobia, anxiety, and somatic disorders (Perwez et al. 2015). Besides this, the disruption in work-life balance was related to poor mental and physical health (Borowiec and Drygas 2022), with the major reason for disruption being quality and hours of work along with personal and social characteristics (Hsu et al. 2019; Aruldoss et al. 2020). In addition, flexible working had a positive impact on workers, facilitating a good work-life balance, and this was especially beneficial for women as they juggled between work and family demands (Chung and van der Lippe 2020) and also promoted work-related well-being (Ray and Pana-Cryan 2021). The duration of work hours is an essential aspect that influences life satisfaction, as well-distributed time between work and leisure activities promotes well-being (Shao 2022). Work demands also influence cognitive abilities (Then et al. 2014; Bufano et al. 2024) and the duration of work shifts (Kazemi et al., 2016).

In addition, the transition in nature of work in the 21st century has the potential influence on mental health due to globalization and technological development (Kawachi 2024) and challenges to occupational safety and health (Felknor et al. 2023). Interestingly, the meaningful experiences and meaning-making capacities of individuals in the workspace were obstacles to depressive symptoms (Bendassolli 2024). Also, there exists a bidirectional association between work injuries and mental health issues (Granger and Turner 2024). In addition, the nature of work that demands verbal ability was associated with higher cognitive functioning among older adults with higher dementia risk (Zülke et al. 2021). This marks the nature of work as a significant social determinant of physical health and mental health (Frank et al. 2023; Kawachi 2024). Although the work-health association is well-established, its psychological implications are still unclear. Furthermore, only minuscule studies have addressed this in the Indian context with this classification of work nature.

The nature of work, work hours, and shift patterns vary across different fields. Certain jobs demand higher physical activity and fewer working hours, while others may require cognitive capabilities with greater working hours. This becomes prominent in a country like India with a larger rural workforce (Chand et al., 2017; Sarkar et al. 2024) that includes diverse work nature. In addition, there is an increase in working age in rural areas (Chattopadhyay et al. 2022). Therefore, it becomes essential to understand the important role of the nature of work in mental health. The present study tried to understand the impact of the nature of work (physical demand, psychological demand, and hazardous work environment) and work-related characteristics on mental health and well-being (life satisfaction, cognitive functioning, and depressive symptoms) among middle-aged and older working adults. A summary of the study’s conceptual framework is presented in Fig. 1.

Methods

Data and sample

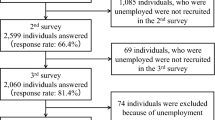

The study used data from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI), Wave 1, collected between 2017 and 2018 from 72,250 ageing adults aged 45 and above. The sample represented participants from India’s states and union territories, excluding Sikkim (International Institute for Population Sciences 2020). In the present study, we included individuals aged between 45 and 70 years who were working with a minimum of one or more years of experience, leading to an analytical sample of 28,653 working adults. Further, after excluding the missing cases for each model with different outcome variables, the study consists of 26,911 older adults for life satisfaction, 23,586 older adults for cognitive functioning, and 26,916 ageing adults for depressive symptoms (Fig. 2).

Variables

Outcome variables

Life satisfaction

The survey used ‘The Satisfaction with Life Scale’ developed by Diener et al. (1985) to assess life satisfaction. The scale consists of five items with seven-point Likert responses (1 – strongly disagree to 7 – strongly agree). The composite life satisfaction score ranges from 5–35, where a higher score indicates a higher level of life satisfaction. The measure showed good reliability (Cronbach α = 0.89).

Cognitive functioning

The cognitive functioning of individuals was assessed through seven cognitive sub-domains that include orientation (time and place), memory (word recall test), arithmetic function (number counting and computation), executive functioning (paper folding and drawing test), and object naming (International Institute for Population Sciences 2020). The composite score ranged from 0 to 43, with a higher score indicating higher cognitive functioning.

Depressive symptoms

The presence of depressive symptoms was assessed using an adapted version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D). The original scale had 20 items (Radloff 1977). The survey used a 10-item measure, seven of which addressed the depressive symptoms while three were related to positive emotions (these items’ scores were reversed). The scale had a four-point Likert scale (1 – rarely or never to 4 - Most or all of the time), with a score ranging from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating higher depressive symptoms. Also, the scale has good reliability with Cronbach α of 0.77.

Predictor variables

Nature of work

This was understood using nine items with a four-point Likert scale (1 - All or almost all of the time to 4 - None of the time or almost never). These nine items were grouped into physical demand (four items), psychological demand (two items), and hazardous work conditions (three items).

Physical demand

The items under physically demanding include responses to the following: “My job requires a) a lot of physical effort, b) lifting heavy loads, c) stooping, kneeling, or crouching, and d) good eyesight”. The score ranges from 4 to 16, with higher scores indicating a lower physical demand for their job requirements. The measure indicated good reliability with a Cronbach α value of 0.74.

Psychological demand

This was assessed using the following two items: “My job requires a) intense concentration or attention and b) skill in dealing with other people”. The composite score ranges from 2 to 8, with a higher score indicating a lower psychological demand in job requirements. This sub-measure showed a satisfactory reliability score (Cronbach α = 0.69).

Hazardous work condition

Similarly hazardous work condition was understood with three items: "My job requires (a) me to be around burning material, exhaust, or smoke (excluding car exhaust)", (b) "me to be close to chemicals/ pesticides/ herbicides" (c) "me to be close to noxious odor". The score ranges from 3 to 12, with a higher score indicating less involvement in hazardous work conditions. The reliability of these items was good, with a Cronbach α value of 0.76.

Other work-related characteristics

This consists of three aspects: work hours in a week, work experience, and frequency of change in work pattern. The work hours and work experience were assessed using the questions “How many hours a week do you work on average at your main job?” and “How long have you been working on this main job, for how many months/years?“, respectively. For work experience, the months were converted to years for the analysis. The frequency of change in work pattern was assessed through the question, “Do you work the same number of hours nearly every week for the weeks you work, or do the hours you work vary a lot from week to week?” with four response options such as same each week, vary a little from season to season, vary a lot from season to season, vary a lot across week within a season.

Health and behavioral factors

Self-rated health (SRH) and morbidity status were considered health-related factors. The response to the SRH question was grouped into ‘good’ by combining the responses of very good, good, and fair and ‘poor’ by merging poor and very poor responses. The morbidity status was identified through the question, ‘Has any health professional ever diagnosed you with the following chronic conditions or diseases?’ the list includes nine diseases, namely hypertension, diabetes, cancer, chronic lung disease, chronic heart disease, stroke, arthritis, any neurological or psychiatric problem, and high cholesterol. The responses were classified as ‘no disease’, ‘one disease’, and ‘multimorbidity’. In addition, the response pattern to behavioral factors such as smoking and alcohol consumption was ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Socioeconomic and demographic factors

We considered age (in years), gender (male or female), marital status (in a union or not in a union), household economic status (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest), social class (Scheduled Tribe (ST), Scheduled Caste (SC), Other Backward Class (OBC) and Others), educational attainment (in years), living arrangement (alone, with spouse and other and with others) and place of residence (rural or urban).

Statistical analysis

We initially conducted descriptive statistical analysis followed by multiple linear regression. The Ordinary Least Square (OLS) technique was adopted for examining the determinants of mental health outcomes. Specifically, in the regression analysis, first, we considered the nature of work variables (physical demand, psychological demand, and hazardous work conditions) as potential determinants of mental health outcomes, namely life satisfaction, cognitive functioning, and depressive symptoms (Model 1: Unadjusted Model). In the fully adjusted model (Model 2), the effect on these mental health outcomes was estimated after adjusting for control variables, including other work-related factors, health and behavioral factors, and socioeconomic and demographic factors. The regression analysis estimates were presented as β coefficients with a confidence interval of 90%, 95%, and 99%. We have estimated Variation Inflation Faction (VIF) for the check of multicollinearity and found no issue of multicollinearity. We have checked for the heteroscedasticity problem using Breusch Pagan Test, and robust standard errors were considered. All the statistical analyses were implemented using Stata version 16.

Results

The present study tried to understand the impact of the nature of work on life satisfaction, depressive symptoms, and cognitive functions. Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics of the study sample. The results showed that life satisfaction, cognitive functioning, and depressive symptoms had a mean score of 23.78, 27.05, and 9.34, respectively. In terms of the nature of work, 8.44, 3.87, and 10.79 were the mean values of physical demand, psychological demand, and hazardous work environment, respectively. It was indicated that the weekly average working hours were 39.84. The mean work experience years was 29.61 years. The mean age of the study population was 55.02 years. The average years of education was 4.44 years.

Regarding the frequency of change in work patterns, 35.49% had no change. However, 21.17% and 3.60% had various changes in their work hours depending on the seasons and across the week, respectively. Considering health and behavior factors, 11.12% of the sample reported poor SRH, 24.28% had one disease, and 11.50% had multimorbidity. 46.23% and 22.13% were involved in smoking and alcohol consumption, respectively. Out of the working population considered in this study, a majority were males (64.24%) than females (35.76%). Further, 15.08% of the study sample were not in a marital union. 83.41% of the study sample were living with spouses and others. Nearly three-fourths of the study population was rural residents.

Table 2 represents the regression analysis results with life satisfaction, cognitive functioning, and depressive symptoms as outcomes. In the unadjusted model, the results showed that the likelihood of life satisfaction increased with the nature of the job with less physical demand (β = 0.18, 99% CI = 0.15–0.22) and less involvement in the hazardous work environment (β = 0.17, 99% CI = 0.12–0.22). However, lower levels of psychological demands in jobs reduced life satisfaction significantly among working adults (β= -0.40, 99% CI= -0.45- -0.35). These results were consistent with the adjusted models. In addition, in the adjusted model, the increase in working hours significantly reduced the likelihood of life satisfaction (β= -0.02, 99% CI= -0.03- -0.01). However, increased work experience predicted higher life satisfaction (β = 0.01, 95% CI = 0.00–0.02). Also, the frequency of changes in work patterns influenced life satisfaction. A higher frequency of changes in work patterns reduced the likelihood of life satisfaction compared to individuals with consistent work hour patterns. In terms of health and behavioral factors, individuals with poor SRH, involvement in smoking, and alcohol consumption reduced the likelihood of life satisfaction (β= -1.77, 99% CI= -2.07 - − 1.48; β= -0.66, 99% CI= -0.84- − 0.47; and β= -0.32, 99% CI= -0.53- -0.12, respectively). Further, the likelihood of life satisfaction increased with age (β = 0.04, 99% CI = 0.02–0.05). Compared to those who were in a marital union, the likelihood of life satisfaction was lower among those who were not in a marital union. Similarly, compared to those living alone, those living with a spouse and others had a higher likelihood of life satisfaction. Along with this, higher economic status and years of education increased the likelihood of higher life satisfaction. The results indicated that in comparison with urban residents, rural residents had a lower likelihood of life satisfaction (β= − 0.24, 95% CI= -0.44 - -0.04).

Similarly, study participants with lower physical demand for work and lower involvement in hazardous work environments indicated a higher likelihood of good cognitive functioning (β = 0.44, 99% CI = 0.41–0.47; β = 0.20, 99% CI = 0.16–0.25, respectively), while lower psychological demand in jobs reduced the likelihood of cognitive functioning (β= -0.57, 99% CI= -0.62 - -0.52). Nonetheless, in the adjusted model, physical and psychological demands did not significantly predict cognitive functioning. However, the result for hazardous work conditions remained the same as in the unadjusted model. Interestingly, although cognitive functioning increased with working hours (β = 0.04, 99% CI = 0.03–0.04), it decreased with greater working hours (β squared= -0.00, 99% CI= -0.00 - -0.00). The likelihood of cognitive functioning decreased with increased work experience (β= -0.02, 99% CI= -0.02 - -0.01). Considering health and behavioral factors, cognitive functioning significantly reduced with poor SRH and alcohol consumption compared to their counterparts. In contrast, participants with one disease and multimorbidity indicated a higher likelihood of cognitive functioning compared to individuals with no disease. It was indicated that cognitive function declined with age (β= -0.07, 99% CI= -0.08 - -0.06). Compared to females, the likelihood of cognitive functioning was higher among males. The likelihood of cognitive functioning was lower among those not in a marital union and those living in rural residence areas. The results showed that cognitive function was significantly increased with more years of education, higher social class, and higher economic status.

Considering the model with depressive symptoms as the outcome, the nature of jobs with less physical demand and lower involvement in hazardous work conditions reduced the likelihood of depressive symptoms (β= -0.04, 99% CI = -0.06 - − 0.03; β= -0.19, 99% CI = -0.21 - − 0.16). The results showed that depressive symptoms increased with lower psychological demands in the job (β = 0.24, 99% CI = 0.21–0.27). Similar results were evident in the fully adjusted model, except for physical demand not being a significant predictor of depressive symptoms. In addition, the work hours reduced depressive symptoms (β= -0.03, 99% CI = -0.04 - − 0.03). However, excessive work hours increased the likelihood of depressive symptoms among working adults (β squared = 0.00, 99% CI = 0.00–0.00). Further, the increase in work experience reduced the likelihood of depressive symptoms (β= -0.01, 99% CI = -0.02 - − 0.01). It was indicated that compared to those with consistent work hour patterns, those with inconsistent work hour patterns increased the likelihood of depressive symptoms.

From the results of health and behavioral factors, it was evident that poor SRH, one disease, and multimorbidity increased the likelihood of depressive symptoms (β = 1.45, 99% CI = 1.29–1.61; β = 0.28, 99% CI = 0.17–0.40; β = 0.54, 99% CI = 0.38–0.70, respectively). Interestingly, it was indicated that the likelihood of depression was lower among those who consume alcohol. Regarding sociodemographic factors, the likelihood of depressive symptoms significantly decreased with age, and those who were living with a spouse and others, from higher economic statuses, and with more years of education. It was found that the likelihood of depressive symptoms increased with being a male, not in a marital union, and among rural residents.

Discussion

The present study tried to understand the role of the nature of work on the mental health and well-being of individuals in terms of life satisfaction, cognitive functioning, and depressive symptoms. This study showed that not being involved in physically demanding and hazardous work environments increased life satisfaction, while not being involved in a psychologically demanding job reduced it. Miniscule studies have focused on the nature of work and its association with life satisfaction. However, studies exist on a related concept of job satisfaction and there is a well-established association between job satisfaction and life satisfaction (Unanue et al., 2017). The results of the present study are consistent with the earlier studies regarding job satisfaction (Bláfoss et al. 2019; Goetz et al. 2013; Andersen et al., 2017). These results may be attributed to potential association with health issues due to increased physical demand (Andersen et al. 2016; Coenen et al. 2014; Hulshof et al. 2021), thus affecting overall life satisfaction. Similarly, this study’s results were consistent with a study by Sunal et al. (2011) among Turkish workers of jean sandblast, which underlined that exposure to dangerous environments was related to poor job satisfaction. The nature of work with no psychological demands increased the likelihood of poor life satisfaction. As mentioned before, minuscule studies have been conducted in these aspects. However, a study suggested that satisfaction is positively impacted when employees’ psychological needs (adequate workload and resources) are satisfied (Fernet et al. 2023).

Furthermore, the work characteristics influenced life satisfaction as increased work hours reduced it, while the increased experiences consistent with little variations in work pattern enhanced life satisfaction. These results have been consistent with the earlier studies that suggested the association between increased work hours and poor life satisfaction (Viñas-Bardolet et al. 2020; Shao 2022). Similarly, earlier studies have evidenced that work experience enhances job satisfaction (Lu 2016; Soni et al., 2017; Wahyudi 2018). Interestingly, this may be due to the work becoming part of the integral self and nourishing life satisfaction, which future studies could test. In addition, the consistency in work patterns may be attributed to their influence on life satisfaction.

Regarding cognitive functioning, the results were similar to those for life satisfaction, and not being involved in a hazardous work environment increased the likelihood of cognitive functioning. These results are consistent with earlier works, which indicated the negative impact of dangerous environments and exposure to metals and noise on cognitive functioning (Grzywacz et al. 2016; Mohammed et al. 2020; Alimoradi et al. 2021). The increase in work hours enhanced cognitive functioning. However, excessive work hours reduced cognitive functioning. Further, increased work experience negatively impacted cognitive functioning. A study found that working up to 25 h per week has positively influenced cognitive functioning. However, it negatively impacted cognitive functioning when it increased beyond its optimal limit (Kajitani et al. 2016). Although minuscule studies have addressed work experience and cognitive functioning, an association exists between work performance and cognitive functioning (Shibaoka et al. 2023). In contrast to this study’s results, the occupational experience positively affected cognitive and health functioning among Korean older adults (Min et al. 2015).

The likelihood of depressive symptoms increased with lower psychological demand in work, while not being involved in a hazardous work environment reduced it. However, to our knowledge, no earlier studies have understood psychological demands from these dimensions and their association with depressive symptoms. The present study characterized psychological demand in two aspects: interaction and concentration. Therefore, the results align with the study, as Lee et al. (2022) pointed out the role of cohesive interaction structure in the workplace and its negative association with depressive symptoms. In contrast, higher emotional demands in the workplace influenced depressive symptoms and mental health (Suh and Punnett 2022). In terms of involvement in hazardous work environments, the results supported the previous works that involvement in hazardous work environments was associated with mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, and elevated stress (Lin et al. 2014; Malekirad et al. 2019; Russo et al. 2019; Vinoth et al. 2023).

In addition, the work hours, work experience, and consistent working patterns reduced depressive symptoms. However, excessive work hours increase the likelihood of depressive symptoms. In line with this evidence, earlier studies have emphasized the importance of work hours per week on the mental health of individuals (Ogawa et al. 2018; Li et al., 2019). There exists a difference between individuals working for 35–40 hours and 60 or more hours in a week in terms of their mental health and depressive symptoms (Milner et al. 2015; Choi et al. 2021). Similarly, a study by Kim et al. (2023) evidenced the requirement of optimal working hours and involvement in social engagement was crucial for reducing the risk of depression among older adults. Even though stress and occupational-related factors are associated with depressive symptoms (Burgard et al. 2013; Kim et al. 2020), to our knowledge, no earlier studies have focused on work experience and work patterns. Further, this can be attributed to the strong identity and certainty in the work aspects.

Considering the health and behavioral factors along with sociodemographic factors, poor SRH, smoking, and alcohol consumption reduced the likelihood of life satisfaction. Poor SRH and alcohol consumption reduced the likelihood of cognitive functioning. The likelihood of depressive symptoms was higher among those who reported poor self-rated health status and morbidity conditions. Contrastingly, the results showed that the likelihood of cognitive functioning was higher among those participants with morbid conditions. These results were supported by earlier works in terms of life satisfaction (Rouch et al. 2014; Grønkjær et al. 2022; Kang 2022), cognitive functions (Muhammad et al. 2021) and depression (Li et al. 2020; Kim and Jang 2021; Singh et al. 2022; Wu et al. 2023), except for the contrasting results in terms of morbidity status and cognitive functioning. This contrasting result could be attributed to the diversity in the method of assessment of the variables, and the factor of working may be over-compensating (Then et al. 2014) for the negative impacts of morbidity on cognitive functioning.

Socioeconomic and demographic factors such as age, gender, years of education, social class, marital status, socioeconomic status, and residence status significantly determine mental health outcome variables. The positive impact of age on life satisfaction evidenced by this study was in line with the works of Kunzmann et al. (2000) and Cho and Cheon (2023). This study’s findings also support the well-established relationship between ageing and declining cognitive function (Murman 2015; Zaninotto et al. 2018) and depressive symptoms (Stordal et al. 2003; Luppa et al. 2012). Further, marital status and living arrangements had a significant influence on mental health outcomes, and these were supported by the literature (Downward et al. 2022; Hsu and Barrett 2020; Jia et al. 2023; Lin et al. 2020). Furthermore, in line with previous works (Möwisch et al. 2021; Muhammad 2023; Pengpid and Peltzer 2024), the study found that those increased in years of education, higher economic status, and those from urban residence areas had a higher likelihood of life satisfaction and cognitive functioning and a lower likelihood of depressive symptoms.

Limitations

This study holds certain limitations. First, the study is based on a cross-sectional design and does not establish a cause-and-effect relationship between the variables under study. Second, some of the variables under the study are based on self-reported information. Although it is one of the practical ways of collecting data for large-scale surveys, it may be subject to recall biases, which is relevant, especially in the ageing population. Third, we considered individuals who engaged only in paid work irrespective of the sector, and therefore, unpaid work like housework, volunteering, etc., were not included in the study.

Conclusion

The study tried to understand the association of the nature of work with life satisfaction, cognitive functioning, and depressive symptoms. The results suggested that individuals working in less physically demanding and not involved in hazardous environments had better life satisfaction. In addition, not being involved in a hazardous work environment increased the likelihood of good cognitive functioning and reduced depressive symptoms. However, work that required less psychological demands led to reduced life satisfaction and increased depressive symptoms. Also, working hours, years of work experience, and work hour patterns were important predictors of life satisfaction, cognitive functioning, and depressive symptoms. In addition, health factors such as SRH, morbidity status, and health behaviors (alcohol consumption and smoking) impacted the mental health and well-being of the working ageing population. Sociodemographic factors also significantly influence life satisfaction, cognitive functioning, and depressive symptoms. It is crucial to note that working adults from rural residences had poor life satisfaction and cognitive functioning and increased depressive symptoms compared to their counterparts.

The results point to the essentiality of less physical demand and reduced involvement in the hazardous work environment for ageing adults. However, a job’s appropriate level of psychological demand is important for good mental health and well-being. Moreover, it is essential to have fair working hours and a consistent working pattern that accommodates the required time for leisure and recreational activities. We also suggest that organizations consider employees’ physical and mental health, especially when there is high physical demand, and work is in a hazardous environment. In addition, it is essential to improve the working conditions of individuals residing in rural areas to improve their well-being. The results of this study facilitate the development of intervention programs and regulations for improving the mental health of working adults, especially those from rural areas.

Data availability

The data used for this study is available through the following website. https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/content/lasi-wave-i or through https://g2aging.org/ .

References

Aazami S, Shamsuddin K, Akmal S, Azami G (2015) The relationship between job satisfaction and Psychological/Physical Health among Malaysian Working Women. Malaysian J Med Sciences: MJMS 22(4):40–46

Ahn J, Kim N-S, Lee B-K, Park J, Kim Y (2021) Comparison of the physical and mental health problems of unemployed with employees in South Korea. Arch Environ Occup Health 76(3):163–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/19338244.2020.1783503

Alimoradi H, Nazari M, Nodoushan RJ, Ajdani A (2021) The Analysis of Harmful Factors Affecting on Mental Health and Cognitive Function among Workers of Steel Industry (using the ISO9612 Approach). Indian J Psychiatric Nurs 18(1):33. https://doi.org/10.4103/IOPN.IOPN_21_20

Andersen LL, Fallentin N, Thorsen SV, Holtermann A (2016) Physical workload and risk of long-term sickness absence in the general working population and among blue-collar workers: prospective cohort study with register follow-up. Occup Environ Med 73(4):246–253. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2015-103314

Aruldoss A, Kowalski KB, Parayitam S (2020) The relationship between quality of work life and work-life-balance mediating role of job stress, job satisfaction and job commitment: evidence from India. J Adv Manage Res 18(1):36–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAMR-05-2020-0082

Bendassolli PF (2024) Work and depression: a meaning-making perspective. Cult Psychol 1354067. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X241226452. X241226452

Bláfoss R, Sundstrup E, Jakobsen MD, Brandt M, Bay H, Andersen LL (2019) Physical workload and bodily fatigue after work: cross-sectional study among 5000 workers. Eur J Public Health 29(5):837–842. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz055

Borowiec AA, Drygas W (2022) Work–Life Balance and Mental and Physical Health among Warsaw specialists, managers and entrepreneurs. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(1):492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010492

Bufano P, Di Tecco C, Fattori A, Barnini T, Comotti A, Ciocan C, Ferrari L, Mastorci F, Laurino M, Bonzini M (2024) The effects of work on cognitive functions: a systematic review. Front Psychol 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1351625

Burgard SA, Elliott MR, Zivin K, House JS (2013) Working conditions and depressive symptoms: a prospective study of U.S. adults. J Occup Environ Med 55(9):1007–1014. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182a299af

Chand R, Srivastava SK, Singh J (n.d.). Changing Structure of Rural Economy of India Implications for Employment and Growth

Chattopadhyay A, Khan J, Bloom DE, Sinha D, Nayak I, Gupta S, Lee J, Perianayagam A (2022) Insights into Labor Force Participation among older adults: evidence from the longitudinal ageing study in India. J Popul Ageing 15(1):39–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-022-09357-7

Cho D, Cheon W (2023) Older adults’ advance aging and life satisfaction levels: effects of lifestyles and Health capabilities. Behav Sci 13(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040293

Choi E, Choi KW, Jeong H-G, Lee M-S, Ko Y-H, Han C, Ham B-J, Chang J, Han K-M (2021) Long working hours and depressive symptoms: moderation by gender, income, and job status. J Affect Disord 286:99–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.001

Chung H, van der Lippe T (2020) Flexible working, work–life balance, and gender Equality: introduction. Soc Indic Res 151(2):365–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2025-x

Coenen P, Gouttebarge V, van der Burght ASAM, van Dieën JH, Frings-Dresen MHW, van der Beek AJ, Burdorf A (2014) The effect of lifting during work on low back pain: a health impact assessment based on a meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med 71(12):871–877. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2014-102346

De Lange * AH, Taris TW, Kompier MAJ, Houtman ILD, Bongers PM (2004) The relationships between work characteristics and mental health: examining normal, reversed and reciprocal relationships in a 4-wave study. Work Stress 18(2):149–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370412331270860

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S (1985) The satisfaction with Life Scale. J Pers Assess 49(1):71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Downward P, Rasciute S, Kumar H (2022) Mental health and satisfaction with partners: a longitudinal analysis in the UK. BMC Psychol 10(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00723-w

Felknor SA, Streit JMK, Edwards NT, Howard J (2023) Four futures for Occupational Safety and Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054333

Fernet C, Morin AJS, Mueller MB, Gillet N, Austin S (2023) Psychological need satisfaction across work and personal life: An empirical test of a comprehensive typology. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1216450

Frank J, Mustard C, Smith P, Siddiqi A, Cheng Y, Burdorf A, Rugulies R (2023) Work as a social determinant of health in high-income countries: past, present, and future. Lancet 402(10410):1357–1367. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00871-1

Goetz K, Musselmann B, Szecsenyi J, Joos S (2013) The influence of workload and health behavior on job satisfaction of general practitioners. Fam Med 45(2):95–101

Granger S, Turner N (2024) Work injuries and mental health challenges: a meta-analysis of the bidirectional relationship. Pers Psychol n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12649

Grønkjær M, Wimmelmann CL, Mortensen EL, Flensborg-Madsen T (2022) Prospective associations between alcohol consumption and psychological well-being in midlife. BMC Public Health 22(1):204. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12463-4

Grzywacz JG, Segel-Karpas D, Lachman ME (2016) Workplace exposures and cognitive function during Adulthood: evidence from National Survey of midlife development and the O*NET. J Occup Environ Med 58(6):535–541. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000727

Hanvold TN, Kines P, Nykänen M, Thomée S, Holte KA, Vuori J, Wærsted M, Veiersted KB (2019) Occupational Safety and Health among Young Workers in the nordic Countries: a systematic literature review. Saf Health Work 10(1):3–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2018.12.003

Hsu T-L, Barrett AE (2020) The Association between Marital Status and Psychological Well-being: variation across negative and positive dimensions. J Fam Issues 41(11):2179–2202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X20910184

Hsu Y-Y, Bai C-H, Yang C-M, Huang Y-C, Lin T-T, Lin C-H (2019) Long hours’ effects on work-life balance and satisfaction. Biomed Res Int 2019:e5046934. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5046934

Hulshof CTJ, Pega F, Neupane S, van der Molen HF, Colosio C, Daams JG, Descatha A, Kc P, Kuijer PPFM, Mandic-Rajcevic S, Masci F, Morgan RL, Nygård C-H, Oakman J, Proper KI, Solovieva S, Frings-Dresen MHW (2021) The prevalence of occupational exposure to ergonomic risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int 146:106157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106157

International Institute for Population Sciences (2020) Data User Guide—Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) Wave 1, 2017-18

Jia Q, Duan Y, Gong R, Jiang M, You D, Qu Y (2023) Living arrangements and depression of the older adults– evidence from the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. BMC Public Health 23(1):1870. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16730-4

Kajitani S, McKenzie C, Sakata K (2016) Use it too much and lose it? The effect of working hours on cognitive ability. SSRN Sch Paper 2737742. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2737742

Kang W (2022) The relationship between smoking frequency and life satisfaction: Mediator of self-rated health (SRH). Front Psychiatry 13:937685. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.937685

Kawachi I (2024) The changing nature of work in the 21st century as a social determinant of mental health. World Psychiatry 23(1):97–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21166

Kazemi R, Haidarimoghadam R, Motamedzadeh M, Golmohamadi R, Soltanian A, Zoghipaydar MR (n.d.). Effects of Shift Work on Cognitive Performance, Sleep Quality, and sleepiness among Petrochemical Control Room operators. J Circadian Rhythm, 14, 1. https://doi.org/10.5334/jcr.134

Kim Y, Jang E (2021) Low self-rated health as a risk factor for Depression in South Korea: a Survey of Young males and females. Healthc (Basel Switzerland) 9(4):452. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9040452

Kim HD, Park S-G, Won Y, Ju H, Jang SW, Choi G, Jang H-S, Kim H-C, Leem J-H (2020) Longitudinal associations between occupational stress and depressive symptoms. Annals Occup Environ Med 32:e13. https://doi.org/10.35371/aoem.2020.32.e13

Kim Y-M, Jang S, Cho S (2023) Working hours, social engagement, and depressive symptoms: an extended work-life balance for older adults. BMC Public Health 23(1):2442. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17072-x

Kunzmann U, Little TD, Smith J (2000) Is age-related stability of subjective well-being a paradox? Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from the Berlin Aging Study. Psychol Aging 15(3):511–526. https://doi.org/10.1037//0882-7974.15.3.511

Lee H-E, Kawachi I (2021) Association between unpredictable work schedules and depressive symptoms in Korea. Saf Health Work 12(3):351–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2021.01.008

Li J, Wang H, Li M, Shen Q, Li X, Zhang Y, Peng J, Rong X, Peng Y (2020) Effect of alcohol use disorders and alcohol intake on the risk of subsequent depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction (Abingdon England) 115(7):1224–1243. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14935

Lin Q-H, Jiang C-Q, Lam T-H, Xu L, Jin Y-L, Cheng K-K (2014) Past occupational dust exposure, depressive symptoms and anxiety in retired Chinese factory workers: the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. J Occup Health 56(6):444–452. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.14-0100-OA

Lin Y, Xiao H, Lan X, Wen S, Bao S (2020) Living arrangements and life satisfaction: mediation by social support and meaning in life. BMC Geriatr 20(1):136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01541-8

Lu Y (2016) The conjunction and disjunction fallacies: explanations of the Linda Problem by the Equate-to-Differentiate Model. Integr Psychol Behav Sci 50(3):507–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-015-9314-6

Luppa M, Sikorski C, Luck T, Ehreke L, Konnopka A, Wiese B, Weyerer S, König H-H, Riedel-Heller SG (2012) Age- and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life—systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 136(3):212–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.033

Malekirad A, Rahzani K, Ahmadi M, Rezaei M, Abdollahi M, Shahrjerdi S, Roostaie A, Nazar B, N. S., Torfi F (2019) Evaluation of oxidative stress, blood parameters, and neurocognitive status in cement factory workers. Toxin Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1080/15569543.2019.1650776

Milner A, Smith P, LaMontagne AD (2015) Working hours and mental health in Australia: evidence from an Australian population-based cohort, 2001–2012. Occup Environ Med 72(8):573–579. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2014-102791

Min J, Park JB, Lee K, Min K (2015) The impact of occupational experience on cognitive and physical functional status among older adults in a representative sample of Korean subjects. Annals Occup Environ Med 27:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40557-015-0057-0

Mohammed RS, Ibrahim W, Sabry D, El-Jaafary SI (2020) Occupational metals exposure and cognitive performance among foundry workers using tau protein as a biomarker. Neurotoxicology 76:10–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2019.09.017

Möwisch D, Brose A, Schmiedek F (2021) Do higher educated people feel better in Everyday Life? Insights from a Day Reconstruction Method Study. Soc Indic Res 153(1):227–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02472-y

Muhammad T (2023) Life course rural/urban place of residence, depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment among older adults: findings from the longitudinal aging study in India. BMC Psychiatry 23(1):391. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04911-9

Muhammad T, Govindu M, Srivastava S (2021) Relationship between chewing tobacco, smoking, consuming alcohol and cognitive impairment among older adults in India: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 21(1):85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02027-x

Murman DL (2015) The impact of age on Cognition. Semin Hear 36(3):111–121. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1555115

Ogawa R, Seo E, Maeno T, Ito M, Sanuki M, Maeno T (2018) The relationship between long working hours and depression among first-year residents in Japan. BMC Med Educ 18(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1171-9

Oliveros B, Agulló-Tomás E, Márquez-Álvarez L-J (2022) Risk and Protective Factors of Mental Health Conditions: Impact of Employment, Deprivation and Social relationships. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(11):6781. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116781

Pengpid S, Peltzer K (2024) Rural-urban health differences among aging adults in India. Heliyon 10(1):e23397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23397

Perwez SK, Khalique A, Ramaseshan H, Swamy TNVR, Mansoor M (2015) Nature of Job and Psychiatric problems: the experiences of Industrial Workers. Global J Health Sci 7(1):288–295. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v7n1p288

Pharr JR, Moonie S, Bungum TJ (2011) The impact of unemployment on Mental and Physical Health, Access to Health Care and Health Risk behaviors. Int Sch Res Notices 2012:e483432. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/483432

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: a self-report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl Psychol Meas 1(3):385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

Ray TK, Pana-Cryan R (2021) Work flexibility and work-related well-being. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(6):3254. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063254

Ronchetti M, Russo S, Di Tecco C, Iavicoli S (2021) How much does my work affect my health? The relationships between Working Conditions and Health in an Italian survey. Saf Health Work 12(3):370–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2021.04.002

Rouch I, Achour-Crawford E, Roche F, Castro-Lionard C, Laurent B, Assoumou N, Gonthier G, Barthelemy R, J.-C., Trombert B (2014) Seven-year predictors of self-rated health and life satisfaction in the elderly: the proof study. J Nutr Health Aging 18(9):840–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-014-0557-6

Russo M, Lucifora C, Pucciarelli F, Piccoli B (2019) Work hazards and workers’ mental health: an investigation based on the fifth European Working conditions Survey. La Medicina Del Lavoro 110(2):115–129. https://doi.org/10.23749/mdl.v110i2.7640

Sarkar S, Menon V, Padhy S, Kathiresan P (2024) Mental health and well-being at the workplace. Indian J Psychiatry 66(Suppl 2):S353. https://doi.org/10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_608_23

Scully-Russ E, Torraco R (2020) The changing nature and Organization of Work: an integrative review of the literature. Hum Resour Dev Rev 19(1):66–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484319886394

Shao Q (2022) Does less working time improve life satisfaction? Evidence from European Social Survey. Health Econ Rev 12(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-022-00396-6

Shibaoka M, Masuda M, Iwasawa S, Ikezawa S, Eguchi H, Nakagome K (2023) Relationship between objective cognitive functioning and work performance among Japanese workers. J Occup Health 65(1):e12385. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12385

Shinohara S (2016) History of Organizations. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance (pp. 1–5). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_1-1

Sinclair RR, Morgan J, Johnson E (2020) Implications of the changing nature of work for Employee Health and Safety. In: Hoffman BJ, Wegman LA, Shoss MK (eds) The Cambridge Handbook of the changing nature of work. Cambridge University Press, pp 489–508. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108278034.023

Singh S, Shri N, Dwivedi LK (2022) An association between multi-morbidity and depressive symptoms among Indian adults based on propensity score matching. Sci Rep 12(1):15518. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18525-w

Soni K, Chawla R, Sengar R (n.d.). Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Employee Experience

Stordal E, Mykletun A, Dahl AA (2003) The association between age and depression in the general population: a multivariate examination. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 107(2):132–141. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02056.x

Suh C, Punnett L (2022) High Emotional demands at work and poor Mental Health in client-facing workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(12):7530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127530

Sunal AB, Sunal O, Yasin F (2011) A comparison of workers employed in hazardous jobs in terms of job satisfaction, perceived job risk and stress: Turkish jean sandblasting workers, dock workers, factory workers and miners. Soc Indic Res 102(2):265–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9679-3

Then FS, Luck T, Luppa M, Arélin K, Schroeter ML, Engel C, Löffler M, Thiery J, Villringer A, Riedel-Heller SG (2014) Association between mental demands at work and cognitive functioning in the general population – results of the health study of the Leipzig research center for civilization diseases (LIFE). J Occup Med Toxicol 9(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6673-9-23

Theorell T, Hammarström A, Aronsson G, Träskman Bendz L, Grape T, Hogstedt C, Marteinsdottir I, Skoog I, Hall C (2015) A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 15(1):738. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1954-4

Unanue, W., Gómez, M. E., Cortez, D., Oyanedel, J. C., & Mendiburo-Seguel, A. (2017). Revisiting the Link between Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction: The Role of Basic Psychological Needs. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 680.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00680

Viñas-Bardolet C, Guillen-Royo M, Torrent-Sellens J (2020) Job characteristics and life satisfaction in the EU: a domains-of-life Approach. Appl Res Qual Life 15(4):1069–1098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09720-5

Vinoth J, Balaji S, Ganesan D, Jain T (2023) Mental Health among Automobile industry workers in Chennai – A cross-sectional study from a single Industrial unit. Int J Occup Saf Health 13:346–352. https://doi.org/10.3126/ijosh.v13i3.47093

Wahyudi W, OF JOB SATISFACTION AND WORK EXPERIENCE ON LECTURER, PERFORMANCE OF PAMULANG UNIVERSITY (2018) Sci J REFLECTION: Economic Acc Manage Bus, 1(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.37481/sjr.v1i2.140

Wright TA, Cropanzano R, Bonett DG (2007) The moderating role of employee positive well being on the relation between job satisfaction and job performance. J Occup Health Psychol 12(2):93–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.2.93

Wu Z, Yue Q, Zhao Z, Wen J, Tang L, Zhong Z, Yang J, Yuan Y, Zhang X (2023) A cross-sectional study of smoking and depression among US adults: NHANES (2005–2018). Front Public Health 11:1081706. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1081706

Zaninotto P, Batty GD, Allerhand M, Deary IJ (2018) Cognitive function trajectories and their determinants in older people: 8 years of follow-up in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Epidemiol Community Health 72(8):685–694. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2017-210116

Zelenski JM, Murphy SA, Jenkins DA (2008) The happy-productive worker thesis revisited. J Happiness Stud 9(4):521–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9087-4

Zülke AE, Luppa M, Röhr S, Weißenborn M, Bauer A, Samos F-AZ, Kühne F, Zöllinger I, Döhring J, Brettschneider C, Oey A, Czock D, Frese T, Gensichen J, Haefeli WE, Hoffmann W, Kaduszkiewicz H, König H-H, Thyrian JR, Riedel-Heller SG (2021) Association of mental demands in the workplace with cognitive function in older adults at increased risk for dementia. BMC Geriatr 21(1):688. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02653-5

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors have not received any funding to carry out this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have equally contributed for the design, analysis and write-up of the paper. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for conducting the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) was guided by the Indian Council of Medical Research. The secondary data used for this study is freely available in the public domain. Hence, no third-party ethical clearance was sought for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sri Lekha, P.P., Abdul Azeez, E., Singh, A. et al. Association of nature of work and work-related characteristics with cognitive functioning, life satisfaction and depression among Indian ageing adults. Int Arch Occup Environ Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-024-02089-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-024-02089-5