Abstract

Objective

To estimate resource use and the costs of eye injuries in 2011–2012 in the Helsinki University Eye Hospital (HUEH), which covers 1.6 million people in Southern Finland.

Methods

This population-based study consisted of all new patients (1,151) with eye injuries in one year. The data were from hospital records, internal HUEH accountancy, and prospectively from questionnaires. The costs of direct health care, transportation, and lost productivity were obtained and estimated for the follow-up period of three months. The estimated future costs were discussed.

Results

During the follow-up, the total cost was 2,899,000 Euros (EUR) (= EUR 1,870,300/one million population), including lost productivity (EUR 1,415,000), direct health care (EUR 1,244,000), and transportation (EUR 240,000). The resources used included 6,902 days of lost productivity, 2,436 admissions and transportations, 314 minor procedures, 313 inpatient days, 248 major surgeries, and 86 radiological images. One open globe injury was the costliest (EUR 13,420/patient), but contusions had the highest overall cost (EUR 1,019,500), due to their high occurrence and number of follow-ups.

Conclusions

Eye injuries cause a major burden through high costs of direct health care and lost productivity: the imminent costs were EUR 1,870,000/one million population, and the future costs were estimated to EUR 3,741,400/one million population. Prevention remains the main factor to consider for better cost-efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eye injuries occur universally in everyday activities and are among the leading causes of monocular blindness in the world [1]. They are mostly predictable and hence, preventable; many of their risk factors have been identified which has led to favorable outcomes through eye safety recommendations [2,3,4,5]. However, they cause an extensive burden to emergency facilities, as well as to socioeconomics through reduced or permanently lost work ability. The impacts of lost productivity may be short term: for example, parents may have to miss work to take care of an injured child; or long term, for example, life-long follow-ups.

It is estimated that 55 million (= 9,500/1,000,000 population) eye injuries occur in the world each year and that 750,000 (= 130/1,000,000 population) injuries require hospitalization [1].

To evaluate the influence of eye injuries, and to set policies for priorities, it is crucial to have information on not only the prevalence and causes, but also on the costs incurred by eye injuries.

Existing reports on the costs incurred by eye injuries from different countries are mostly outdated. Moreover, the comparability of these studies is limited due to different insurance and compensation policies, or developmental diversity. Many studies have a narrow focus; for example, they report the expenses of preventable and minor [6], or serious eye injuries [7, 8], or those caused intentionally, at work, or among children [7, 9, 10].

Few studies have reported the cost of all eye injuries. Mönestam estimated a total cost of eye injuries of SEK 1,300,000 (= ca. EUR 197,400 [11]) in a hospital with a population base of 115,000 in Northern Sweden in 1986 [12].

Many studies have addressed inpatient days and lost productivity days [13,14,15,16,17]. Median hospitalization costs of ocular injuries in Texas were between USD (United States Dollars) 34,576 and USD 55,409 (= EUR 26,000 and EUR 42,000 [11]) for a 2- to 4-day hospital stay during 2013–2014 [16].

In Finland in 1980–1986, perforating eye injuries caused 5% of permanent disability and inability to work [8].

To our knowledge, no recent studies have described direct and indirect costs, the use of resources, or the costs incurred by serious and minor eye injuries in European countries.

The strength of our study is that it is a population-based study. The aim of this study was to estimate the economic burden and resources used for eye injuries in Southern Finland from a societal perspective, including direct health care costs, direct non-health care costs, and indirect costs.

Materials and methods

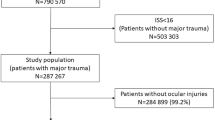

In this population-based study, the participants consisted of all new patients with an eye injury admitted to the Helsinki University Eye Hospital (HUEH) emergency department (ED) over one year (1 May 2011 to 30 April 2012).

Data was obtained prospectively from patient questionnaires and retrospectively from hospital records. These included information on patient demographics, symptoms, detailed physical eye examinations, treatments, use of resources, and the cause of and events leading to the eye injury. The follow-up period was three months. We divided the cases into three age groups: children aged under 17 years, adults aged 17–60 years, and the elderly aged over 60 years. We classified the ICD-10-coded (International Classification of Diseases-10) cases as BETTs (Birmingham Eye Trauma Terminology system) [18, 19] and into seven diagnostic groups according to their primary diagnosis. These were chemical and burn eye injuries, contusions, orbital fractures, open globe injuries (OGI), optic nerve injuries (ONI), superficial minor eye injuries, and eyelid wounds with or without lacrimal injuries (Table 1) [20,21,22].

The costs were grouped into direct and indirect costs. Direct costs included health care costs and non-health care costs. Direct health care costs included outpatient visits, hospitalizations, major surgeries, minor procedures, and medication and radiology costs. Direct non-health care costs included transportation costs. Indirect costs included the costs of lost productivity.

We derived the unit cost for outpatient visits, hospitalizations, major surgeries, and minor procedures from the internal HUEH cost accounting data [23].

Outpatient admissions were calculated for the three age groups as well as for all diagnostic groups. This included number of admissions of the first visits in the Emergency Department (ED) + the first control visits in ED clinic + the following possible follow-up visits at an eye sub-specialty clinic during three months of follow-up.

The cost of hospitalizations was based on the number of inpatient days.

The major surgeries included the services of an anesthesiologist (sedation or general anesthesia). The unit costs were obtained from resourced-based internal HUEH cost accounting data. The unit cost was different for an emergent and for an elective operation (Table 2). In the case of several simultaneous operations, the cost included the most expensive procedure added to half of the sum of the other procedures.

The number of minor procedures was calculated for the three age groups as well as for all diagnostic groups. To calculate the costs of each case, we used the internal resourced-based HUEH cost accounting data (Table 2).

The unit cost of medication was obtained from the Finnish Medical Society’s national health portal [24].

The unit costs for transportation were obtained from the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, KELA, and the Department of Health and Welfare [25,26,27]. The total transportation cost was the sum of costs for two groups: patients receiving, and patients not receiving a travel allowance.

Lost productivity was estimated by multiplying the number of days absent from work by the employee’s average daily cost of lost productivity, for patients aged 17–64 and for one parent of the injured children needing physical restriction (Table 2). The number of days of lost productivity included the days of sick leave resulting from the eye injuries, imminent surgeries, admissions, and follow-up visits. The lost productivity costs were based on the wages of all employees in Finland added to the employers’ social security contributions and divided by the number of all employees [28, 29].

Costs during follow-up

On the last visit, the data obtained included main abnormal status findings, outpatient admissions, days of hospitalization, major surgeries, minor procedures, medication, and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The unit and total costs by age group and the mean direct, indirect, and total costs during follow-up were estimated, in different diagnostic groups. The total cost per one million population was obtained. The costs were represented in euros, aligned with the Finnish health care producer price index 2020 [30].

Estimating the future costs after follow-up

The estimations of the future costs after follow-up are presented in supplementary Tables 1–3, [36,37,38,39,40] and in supplementary Fig. 1 and discussed in the “Discussion” section.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Helsinki–Uusimaa Hospital District and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Resource use and costs during follow-up period

Of the 1151 patients, 202 were children aged under 17, 831 were adults aged 17–60, and 118 patients were over 60 years old.

Resource use

Table 2 shows resource use as follows:

-

The number of outpatient visits was 2,436. Children needed 444 (mean 2.2), adults 1,722 (mean 4.1), and seniors 270 visits (mean 2.3).

-

The number of major operations was 248 for 149 patients. Fourteen percent (28) of children, 12% (97) of adults, and 20% (24) of seniors underwent surgery. The number of minor procedures was 314 for 301 patients.

-

Inpatient days were 313 for 90 patients. Eight percent (17) of children, 7% (57) of adults, and 14% (16) of seniors needed inpatient care.

Medication was used by 1,024 patients for 13,512 days (mean 13, range 1–215 days).

We estimated that 84 patients had to undergo 86 imaging of the head (76 CTs, 10 MRIs).

Based on the location of the patients living in HUEH area, 54.8–76% received a travel allowance of EUR 51.98/trip, after paying a deductible of EUR 9.25/trip. The transportation cost for patients not receiving the travel allowance was estimated to be EUR 9.25/trip [25,26,27].

A total of 6,902 days of lost productivity were needed for 825 people (mean 8.9; median 3; mode 3; range 1–313 days). From this amount of lost productivity, major operations caused 2470 days of lost productivity (100 operated patients of working age had 2,195 days, and 28 parents of operated children had 275 days).

Costs

The total cost was EUR 2,899,000 for 1151 patients and EUR 1,870,000 per one million population. This included lost productivity (49%), direct health care (43%), and transportation costs (8%) (Fig. 1). The total mean cost was EUR 2,515/patient (Table 1).

Direct health care costs amounted to EUR 1,244,000 (Table 2). This included the costs of outpatient visits (41%), major surgeries (35%), inpatients (19%), medication (2%), minor procedures (2%), and radiology (1%).

The total transportation cost was EUR 240,000 (Table 2, Fig. 1).

The mean total cost was EUR 2,080/child, EUR 2,590/adult, and EUR 2,730/senior. The mean cost by diagnostic group varied between EUR 1,010 and EUR 13,420 per patient. The lowest cost was for minor superficial injuries at EUR 1,010/patient, and the two most costly diagnostic groups were OGI at EUR 13,420/patient and optic nerve injuries at EUR 10,490/patient (Table 1).

Discussion

The present study shows that eye injuries cause a considerable economic burden. The costs of eye injuries were EUR 421,000 for children, EUR 2,156,000 for the adults, and EUR 322,000 for the elderly during the follow-up period of 1 year. A total cost of EUR 2,899,000 and 6,902 days (= 19 years) of lost productivity were incurred by all new eye injuries that occurred during the 1-year study period in a population of 1.55 million. Contusions (2,922 days, 42%) and superficial minor injuries (1,466 days, 21%) were the largest diagnostic groups that caused lost productivity.

An annual direct and indirect cost of USD 5 million (EUR 7,3 million [11]) and a loss of 60 work years was estimated among 3,184 patients with ocular injuries presenting to the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Emergency Service over a period of 6 months in 1985. This included outpatient visits and hospitalizations but excluded orbital and facial fractures [13].

In the present study, outpatient visits incurred the greatest cost among the direct health care costs, in the follow-up period.

The number of days as inpatient and as lost productivity caused by OGI has varied in previous studies. The mean length of hospital stay for perforating eye injuries in HUEH in Finland was 26 days in the 1950s [31], 20 days in the 1970s–1980s [8, 32], and 9.6 days in the present study. The mean length of lost productivity was 49 days in the 1970s [32], 90 days in the 1980s [8], and 54 days in the present study.

The health care cost level is lower in Finland than in the other Nordic countries and the USA [33, 34]. This may result in a relatively lower economic burden of eye injuries than in the mentioned countries. Comparison between reports on the costs of eye injuries is challenging, not only due to different health care cost levels, but also due to different study designs and focuses of interest.

A few other previous studies have reported data on the costs of hospitalization. According to Iftikhar et al., the median inpatient costs for eye injury in the USA was USD 11,000 (EUR 8000) in 2014 [14]. In Taiwan in 2001–2002, the mean hospitalization cost of a serious eye injury was USD 900–1,400 [15] (EUR 960–1,500) [11].

In the present study, during the follow-up period, the total mean costs per patient varied between EUR 1,010 for a minor superficial injury and EUR 13,420 for OGI. However, minor superficial eye injuries surprisingly had the second highest overall costs (EUR 609,600), after contusions (EUR 1.02 million), due to their highest occurrence among all diagnostic groups. In Croatia, the costs of minor eye injuries were EUR 135,500 in 2002–2003 [6].

We estimated the future costs incurred by the studied population (supplementary Tables 1–3 and supplementary Fig. 1).

The costs caused by 331/1,151 patients after the follow-up period (EUR 5,799,200) derived mainly from the high number of life-long follow-ups. After the follow-up, the estimated total mean cost per patient varied between EUR 470 for a minor superficial injury and EUR 20,110 for a contusion. The cost by a contusion was mainly due to the required high number of life-long follow-up visits (supplementary Tables 1–3). The total cost of eye injuries (EUR 8.7 million) during and after the follow-up, together, consisted of indirect costs for lost productivity (EUR 3.9 million, 44%), direct health care costs (EUR 3.4 million, 39%), and transportation costs (EUR 1.4 million, 17%) (supplementary Fig. 1). This total cost (EUR 8.7 million) corresponds to EUR 5.61 million/one million population (= costs during follow-up 1.870 million per one million population + estimated future costs 3.741 million per one million population).

The limitations of this study include, first, its short clinical follow-up time. A longer follow-up would give more accurate estimates of future required surgeries, admissions, and costs. The present study included only imminent future surgeries. Second, we lacked data on the costs of patients who are dependent on a caregiver (very old patients with a serious underlying disease, people with dementia, the disabled). Third, we lacked data on the far-reaching future economic burden caused by permanently impaired patients. As we reported previously [20,21,22], 107 patients (19 children, 73 adults, and 15 elderly people) had a permanent visual or functional impairment. The impact of this is apparent on one’s profession as reduced or lost productivity. Fourth, our estimations did not include costs of rehabilitation and vision aids such as eyeglasses and contact lenses. All these limitations underestimate the total costs of eye injuries. On the other hand, because of the use of the human capital method, the cost of productivity loss may be overestimated, and further studies are encouraged.

The future costs were presented in their nominal value; hence, discount rate was set to zero as the Finland Government Bond 10-year reference has been continuously negative starting from 24.4.2020 except a short period in May 2021 [35]. Discounting rate is ambiguous in the present state of the world economy. However, if previously used discount rates were used, the discounted present value of the future costs would be lower than in the present study.

One of the strengths of the present study is that it is a population-based study, as HUEH is practically the only ophthalmology acute care trauma unit in the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District in urban and rural Southern Finland and covers approximately 29% of the population of Finland. Some minor eye injuries may have been treated in private care outpatient clinics, but these operate mainly by appointment and do not offer acute eye injury care or treatment. Another strength of the study is its size which was suitably representative of a sparsely populated country such as Finland. Other strengths are that the study reported the costs of both major and minor eye injuries in the clinical follow-up period as well as life-long costs.

In conclusion, eye injuries lead to considerable use of resources and costs in both the short and the long term. Knowledge of the burden and costs that eye injuries cause helps decision-makers set policies for priorities, helps prevent eye injuries, and may improve cost-efficiency.

Policies should be set to prevent eye injuries, based on the preventable nature of these injuries, at individual and community levels. Compliance with safety regulations and measures at work and at home should be increased by enhancing people’s general knowledge about the risks and costs of eye injuries. The detailed savings and health-promoting effects of prevention remain to be shown by further studies.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Négrel AD, Thylefors B (1998) The global impact of eye injuries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 5(3):143–169. https://doi.org/10.1076/opep.5.3.143.8364

Leivo T, Puusaari I, Mäkitie T (2007) Sports-related eye injuries: floorball endangers the eyes of young players. Scand J Med Sci Sports 17(5):556–563

Kivelä T (2014) Ilotulitteiden aiheuttamat silmävammat vähenivät jo neljättä vuotta. Annual report SSLY. http://www.silmalaakariyhdistys.fi/fin/ajankohtaista/index.php?2014-1-Ilotulitteiden-aiheuttamat-silmavammat-vahenivat-jo-neljatta-vuotta&nid=78. Accessed 2 October 2020

Vinger PF (1998) Sports medicine and the eye care professional. J Am Optom Assoc 69(6):395–413

Vinger PF (2000) A practical guide for sports eye protection. Phys Sportsmed 28(6):49–69. https://doi.org/10.3810/psm.2000.06.961

Loncarek K, Brajac I, Filipoviæ T, Èaljkušiæ-Mance T, Štalekar H (2004) Cost of Treating Preventable Minor Ocular Injuries in Rijeka, Croatia. Croat Med J 45(3):314–317

Fong LP, Taouk Y (1995) The role of eye protection in work-related eye injuries. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 23(2):101–106

Punnonen E (1989) Epidemiological and social aspects of perforating eye injuries. Acta Ophthalmol 67(5):492–498

Hemady RK (1994) Ocular injuries from violence treated inner-city hospital. J Trauma 37(1):5–8

Luo H, Shrestha S, Zhang X, Saaddine J, Zeng X, Reeder T (2018) Trends in eye injuries and associated medical costs among children in the United States 2002–2014. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 25(4):280–287

Laurent P (2001) Historical currency converter. https://fxtop.com/en/historical-currency-converter.php?A=0&C1=USD&C2=EUR&DD=01&MM=01&YYYY=1986&B=1&P=&I=1&btnOK=Go%21. Accessed 19 March 2021

Mönestam E, Björnstig U (1991) Eye injuries in Northern Sweden. ACTA Ophthalmol 69:1–5

Schein OD, Hibberd PL, Shingleton BJ, Kunzweiler RN, Frambach DA, Seddon JM, Fontan NL, Vinger PF (1988) The spectrum and burden of ocular injury. Ophthalmology 95(3):300–305

Iftikhar M, Latif A, Usmani B, Canner JK, Shah SMA (2019) Trends and disparities in inpatient costs for eye trauma in the United States (2001–2014). Am J Ophthalmol 207:1–9

Cheng-Hsien C, Chang-Ling C, Chi-Kung H, Yu-Hong L, Ru-Chuan H, Ya-Lin Y (2008) Hospitalized eye injury in a large industrial city of South-Eastern Asia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 246:223–228

Nelson PC, Mulla ZD (2020) The cost of hospitalized ocular injuries in Texas 2013–2014. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 27(5):409–416

Ojuok E, Uppuluri A, Langer PD, Zarbin MA, Thangamathesvaran L, Bhagat N (2020) Demographic trends of open globe injuries in a large inpatient sample. Eye. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-01249-4

Kuhn F, Morris R, Witherspoon CD, Mester V (2004) The Birmingham Eye Trauma Terminology system (BETT). J Fr Ophtalmol 27:206–210

International Society of Ocular Trauma (ISOT). http://isotonline.org/betts/. Accessed 10 October 2020

Sahraravand A, Haavisto AK, Holopainen JM, Leivo T (2017) Ocular traumas in working age adults in Finland— Helsinki Ocular Trauma Study. Acta Ophthalmol 95(3):288–294

Sahraravand A, Haavisto AK, Holopainen JM, Leivo T (2018) Ocular traumas in the Finnish elderly—Helsinki Ocular Trauma Study. Acta Ophthalmol 96(6):616–622

Haavisto AK, Sahraravand A, Holopainen JM, Leivo T (2017) Paediatric eye injuries in Finland-Helsinki eye trauma study. Acta Ophthalmol 95(4):392–399

The internal HUEH cost accounting data, The Service Price List (2020) HUS Palveluhinnasto 2020. https://www.hus.fi/tietoa-meista/hallinto-ja-paatoksenteko/talous/hinnoittelu. Accessed 5 November 2020

The Finnish Medical Society’s national health portal. Terveysportti. https://www.terveysportti.fi/terveysportti/laakkeet.koti?p_tyyppi=&p_hakuehto=&p_valilehti=. Accessed 11 November 2020

The Social Insurance Institution of Finland. KELA, Kansaneläkelaitos. Sairaanhoitokorvausten saajat/ Matkat. http://raportit.kela.fi/ibi_apps/WFServlet?IBIF_ex=NIT130AL. Accessed 5 October 2020.

The Social Insurance Institution of Finland. KELA, Kansaneläkelaitos. https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-8631095#:~:text=Kelan%20matkakorvausten%20omavastuu%20on%20noussut,omavastuu%20oli%209%2C25%20euroa.&text=Matkojen%20omavastuuta%20on%20nostettu%20viime%20vuosina%20useaan%20otteeseen. Accessed 5 November 2020

Häkkinen U, Peltola M (2014) Sairausvakuutuksen korvaamien matkojen kustannukset erikoissairaanhoidossa Tuloksia PERFECT-hankkeesta. Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos, THL 20/2014. Table 23. Page 33. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-302-228-7. Accessed 15 November 2020

Kapiainen S, Väisänen A, Haula T (2014) Terveyden- ja sosiaalihuollon yksikkökustannukset Suomessa vuonna 2011. Raportti 3/2014. Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-302-079-5. Accessed 17 October 2020

Statistics Finland. Tilastokeskus. https://www.stat.fi/til/pal.html. Accessed 11 December 2020

Statistics Finland. Tilastokeskus. PxWeb-tietokannat. http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/StatFin__hin__pthi/statfin_pthi_pxt_117v.px/table/tableViewLayout1/. Accessed 12 December 2020

Niiranen M (1978) Perforating eye injuries. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl (Copenh) 135:1–87

Niiranen M (1981) Perforating eye injuries treated at Helsinki University Eye Hospital 1970 to 1977. Ann Ophthalmol 13:957–961

Finland: Country Health Profile 2019. https://www.oecd.org/publications/finland-country-health-profile-2019-20656739-en.htm. Accessed 22 February 2021

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical#:~:text=U.S.%20health%20care%20spending%20grew,spending%20accounted%20for%2017.7%20percent. Accessed 22 February 2021

Trading Economics. Finland Government Bond 10Y. 1991–2021 Data. 2022–2023 Forecast. Quote.Chart. https://www.tradingeconomics.com. Accessed 23 February 2021

Rouberol F, Denis P, Romanet JP, Chiquet C (2011) Comparative study of 50 early- or late-onset retinal detachments after open or closed globe injury. Retina 31(6):1143–1149

Girkin CA, JrG McGwin, Long C, Morris R, Kuhn F (2005) Glaucoma after ocular contusion: a cohort study of the United States Eye Injury Registry. J Glaucoma 14(6):470–473

Sihota R, Sood NN, Agarwal HC (1995) Traumatic glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 73(3):252–4

Life expectancy. Findikaattori – Elinajanodote. https://findikaattori.fi/fi/46#:~:text=Tilastokeskuksen%20mukaan%20vastasyntyneiden%20poikien%20elinajanodote,laskenta%2Dajanjaksolla%20havaitun%20kuolleisuuden%20tasoa. Accessed 30 November 2020

Eurostat. Your Key to European Statistics. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tps00026&plugin=1. Accessed 30 November 2020

Funding

This research was supported by grants from The Finnish Ophthalmological Foundation, The Finnish Eye and Tissue Bank Foundation, and The Association of Finland’s Ophthalmologists. Open access funding is provided by Helsinki University, Helsinki, Finland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

All listed authors have provided consent for publication of this article.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sahraravand, A., Haavisto, AK. & Leivo, T. Resource use and economic burden of eye injuries in Southern Finland. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 260, 637–643 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-021-05399-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-021-05399-3