Abstract

The treatment landscape for relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (RMS) has expanded considerably over the last 10 years with the approval of multiple new disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), and others in late-stage clinical development. All DMTs for RMS are believed to reduce central nervous system immune-mediated inflammatory processes, which translate into demonstrable improvement in clinical and radiologic outcomes. However, some DMTs are associated with long-lasting effects on the immune system and/or serious adverse events, both of which may complicate the use of subsequent therapies. When customizing a treatment program, a benefit–risk assessment must consider multiple factors, including the efficacy of the DMT to reduce disease activity, the short- and long-term safety and immunologic profiles of each DMT, the criteria used to define switching treatment, and the risk tolerance of each patient. A comprehensive benefit–risk assessment can only be achieved by evaluating the immunologic, safety, and efficacy data for DMTs in the controlled clinical trial environment and the postmarketing clinical practice setting. This review is intended to help neurologists make informed decisions when treating RMS by summarizing the known data for each DMT and raising awareness of the multiple considerations involved in treating people with RMS throughout the entire course of their disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The unpredictable nature of multiple sclerosis (MS) clinical manifestations within and between patients with apparently similar characteristics is brought about by a complex and dynamic pathophysiology involving inflammatory-based mechanisms of demyelination and axon loss [1,2,3]. A range of genetic [4, 5], immunopathologic [6,7,8], and environmental/epigenetic [9] factors drive the tremendous variability in the type, frequency, and severity of signs and symptoms that may present during the course of MS [10, 11].

Despite the heterogeneity in MS disease course, selecting an appropriate therapy for relapsing forms of MS (RMS) before the approval of fingolimod in 2010 [12, 13] was relatively simple because neurologists had two main treatment options: interferon beta/glatiramer acetate or natalizumab. The beta interferons and glatiramer acetate have comparable long-term safety profiles and efficacy, reducing the frequency of relapses by ~30% over a 2- to 3-year treatment period, as evaluated in clinical trials [1, 2, 14]. However, a high proportion of patients experience breakthrough disease or have persistent clinical or radiologic disease activity within 2 years of treatment initiation of these agents [14, 15]. Conversely, the safety of interferon beta and glatiramer acetate over two decades is highly favorable and the relative risk for immunologic complications is low [14, 16,17,18]. Natalizumab [19, 20] is more efficacious than interferon beta and glatiramer acetate [21, 22], but has a complex safety profile due to the risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) [19, 20]. For this reason, historically, natalizumab was generally reserved for patients requiring higher efficacy than interferon beta and glatiramer acetate, and, more recently in the US, only when the expected benefit is sufficient to offset PML risk [19, 20, 23].

Since 2010, new disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) have emerged [18]; 13 approved DMTs are currently available to treat RMS worldwide (Table 1), which target different pathways of the immune system (Table 2). Several of the new DMTs have demonstrated superior efficacy over either interferon beta or glatiramer acetate in Phase III studies of patients with RMS (Table 3). While there may be differences in their relative efficacy, additional head-to-head clinical trials, particularly comparator studies between oral DMTs, are required to confirm and quantify this assertion [24]. Oral DMTs such as teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, and fingolimod offer a convenient route of administration, while peginterferon beta, daclizumab beta, ocrelizumab, and alemtuzumab provide a lower dosing frequency, being dosed once every 2 weeks, monthly, every 6 months, and annually, respectively.

Although the expansion in treatment options for RMS is welcome, health care professionals are now faced with complicated decisions on how to individualize initial therapy for patients (see Table 4 for prognostic features in MS) and then select subsequent therapies, based on incomplete benefit–risk assessments of the current and potentially unknown long-term immunologic and safety risks. The most important knowledge deficit is the long-term safety of newly approved DMTs for RMS, which may not have been fully elucidated during their Phase III clinical trial programs, and thus may place some patients at risk for complications yet to be defined. For instance, some DMTs for RMS have been associated with adverse events (AEs) that only came to light during postmarketing surveillance [16, 25], culminating in the development of intensive risk reduction strategies to optimize patient safety such as classifications of PML risk [26]. Other generic factors preventing the extrapolation of data to a real-world setting include strict patient selection and high motivation in clinical trials.

The purpose of this review is to raise awareness of the issues involved in sequencing RMS therapies by discussing the immunologic effects and known safety profiles of available DMTs. In doing so, the treating neurologist may be better able to inform patients on the likely benefits and risks of treatment.

General principles of treatment sequencing in RMS

The primary aim of treatment is to reduce disease activity to optimize neurologic reserve, cognition, and physical function [27]. Meeting this goal requires a concordant relationship between the health care professional and patient so that the personal preferences of the patient are considered when developing or revising the treatment plan (shared decision making). Patients should be informed that different DMTs may be required at different times because of suboptimal response, safety concerns, intolerable side effects to the DMT, or a change in the risk tolerance of the patient. Within this context, patients could be made aware of commonly used criteria necessitating a treatment switch due to suboptimal response. For interferon beta recipients specifically, the Rio score estimated after 1 year of treatment is prognostic for ongoing disease activity in the ensuing 3 years [28, 29]. For DMTs more generally, the Canadian Multiple Sclerosis Working Group recommends changing treatment when there is a low level of concern in all three domains of the MS disease status triad [relapses, disability progression, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)], a medium level of concern in any two domains, or a high level of concern in any one domain [30]. Another example is the multifactorial MS decision model that, by grading the four domains of relapse, disability progression, MRI, and neuropsychology, aims to support early treatment decisions and detect treatment failure in a timely manner [31].

Regardless of the clinical criteria used to identify suboptimally controlled RMS [30, 32], treatment sequencing is often necessary to maintain disease control, which may introduce an additional safety risk [30]. Neurologists have two major decisions regarding the prescription of DMTs: (1) choosing the initial DMT expected to reduce disease activity while recognizing the potential need for alternative later-line DMTs if the response is suboptimal; and (2) selection of subsequent treatment choices based on previous DMT use. The appropriate course of action selected depends on a thorough benefit–risk evaluation for each candidate DMT after accounting for specific disease- and patient-related factors at a specific point in time, as well as the patient’s access to DMTs through their health insurance plans.

Treatment algorithms for RMS that rank DMTs as first and second line have been proposed [33, 34], as have the pros and cons of induction (starting highly effective therapy earlier in the course of the disease) versus escalation treatment paradigms [35, 36]. However, the initial DMT should provide the most favorable benefit–risk profile given the level of disease activity over the last 6–12 months, taking into account the MS type, long-term prognostic factors (Table 4), patient-related factors, and the fact that the risk of AEs associated with some DMTs can change over time. Importantly, due to the heterogeneity of RMS, the choice of starting DMT should take into consideration potential future treatment needs by keeping subsequent treatment options open (e.g., reserving the need for DMTs with a long-lasting immunoablative impact on the immune system until a later time if appropriate). Like a good chess player who thinks several moves ahead, performing multiple benefit–risk assessments across several DMTs for RMS is required when reviewing medication at any point in time.

Escalation versus induction

Clinicians may deliberate on the relative value of an escalation or induction treatment approach. A treatment escalation approach is based on starting with a relatively safer agent and reactive treatment switches due to breakthrough disease. At every stage in the patient’s disease course, there can be lasting effects of previous DMTs on the patient’s immune system, especially with medications that have prolonged immunologic sequelae. When switching from the initial DMT, it is imperative to consider the mechanism of action and duration of pharmacodynamic and immune system effects because these can impact the efficacy and safety of the next agent. Patients with moderate disease activity [one disabling relapse in the last year and/or two new gadolinium-enhancing (Gd+) lesions, or accumulation of two new T2 lesions per year, indicating multifocal attacks] or high disease activity (at least one disabling relapse in 1 year plus at least three new Gd+ lesions, or accumulation of three new T2 lesions per year) may be placed on a high-efficacy treatment early in the disease course and continue with that DMT [24, 30]. Some therapies with reversible mechanisms of action facilitate escalation of therapy towards other agents within a relatively short time frame of discontinuation if safety considerations allow, whereas other DMTs with long-term effects on the immune system after treatment cessation can limit the scope of subsequent pharmacotherapy. The latter DMTs also have been used as induction therapies.

Induction involves short-term use of a high-efficacy treatment to obtain rapid control of highly active disease and to increase the likelihood of beneficial long-term outcomes [35, 37], justifying an increased risk of serious AEs. The induction strategy is generally intended for younger patients (<40 years of age) with aggressive RMS who may have already received immunomodulatory drugs, with frequent (at least two) and severe relapses within the last 12 months, neuroradiologic activity (at least two additional Gd+ lesions on recent T2 MRI), and who are at increased risk of rapid accumulation of disability (e.g., high relapse rate in the first 2–5 years and short first interattack interval) [33, 35, 38], and people of African descent [39]. Before an induction strategy is initiated, physicians must consider the appropriate maintenance DMT postinduction but, in practice, this is not always possible and data to guide postinduction choices are very limited.

The range of available induction therapies is fairly narrow, and includes mitoxantrone, alemtuzumab, and to a limited extent, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (within a clinical trial setting). Off-label cyclophosphamide also has been investigated in patients with highly active disease [40]. There are positive neuroradiologic data for the brief use of immunosuppressive induction therapy with mitoxantrone before maintenance therapy with glatiramer acetate in patients with highly active RMS [41, 42]. However, the safety profile of the induction agent may preclude many patients from receiving this treatment strategy. Use of either immunoablative chemotherapy or immune-depleting antibodies followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has been successful in treating patients with MS [43,44,45]. The immune-depleting antibody alemtuzumab may be considered as an induction therapy because its effects on the immune system persist long after treatment cessation, enabling dosing on a one-off or annual basis [37]. In contrast, the high-efficacy DMTs fingolimod and natalizumab should not be considered as induction therapies because their rapidly reversible mechanisms of action predispose patients to a quick return of disease activity following treatment cessation [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. For a similar reason, it is likely that daclizumab beta should be used as a maintenance high-efficacy DMT rather than as an induction therapy [54, 55].

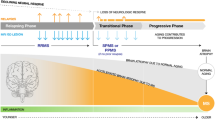

Clinical pharmacology, safety, and monitoring of DMTs

Most DMTs have a clear pharmacodynamic drug–drug interaction by virtue of their temporal effects on immune cell counts and functions (Table 2). Because different DMTs exert distinct immunologic effects that persist for variable periods of time after discontinuation, the immune system may not have fully recovered to its pretreatment baseline physiologic composition during transition from one DMT to another. The type and duration of effect of the previous DMT not only influences the selection of the subsequent DMT, but also the known and unknown risk of an AE with the later-line DMT. As currently understood, the armamentarium of approved and investigational agents for MS can be grouped into DMTs that exert near-term effects on the immune system [day-to-week timescale: interferon beta-1a and 1b, peginterferon beta-1a, glatiramer acetate, dimethyl fumarate, teriflunomide (if an accelerated elimination procedure with activated charcoal or cholestyramine is used)], mid-term immunologic effects (week-to-month timescale: fingolimod, natalizumab, and daclizumab beta), and long-term immunologic effects [month-to-year timescale: mitoxantrone, teriflunomide (if the rapid elimination procedure is not implemented), alemtuzumab, and ocrelizumab]. A more precise classification of the immunologic half-lives of DMTs will be possible once their effects on lymphocyte subpopulations are better understood. The safety profile and immunologic effects of interferon beta and glatiramer acetate are such that an immediate transition to another DMT is possible, providing there are no obvious abnormalities on clinical biochemistry.

Arguably, a transition period between stopping the existing DMT and initiating a new DMT may be unnecessary with some of the newer DMTs, but there is a fine balance between the duration of washout (if any) and risk of disease. For instance, the immunologic effect of alemtuzumab persists long after cessation of therapy and is unrelated to its biologic half-life, which may expose patients to immune-mediated risks when they are switched to subsequent DMTs. However, aggressive rebound disease activity can resume shortly after stopping one agent and initiating another, as has been observed with natalizumab and fingolimod [46,47,48, 51], suggesting that better outcomes may be seen with shorter washout. Another point for consideration is whether a previous drug could potentially nullify or attenuate the mode of action of later-line therapies: would the B and T cell-depleting action of alemtuzumab occur immediately after use of fingolimod if lymphocytes have not yet exited from secondary lymphoid tissue? Hence, the diverse interactions of DMTs with the immune system underscore their efficacy and safety profile, which, in turn, guides patient monitoring.

The increased efficacy and/or patient convenience associated with newer DMTs relative to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate must be balanced against known and unknown safety issues. DMTs have the potential to produce on- and/or off-target-based toxicities that manifest as unexpected serious AEs. Safety concerns for some therapies only became evident during extension studies and postmarketing surveillance studies, requiring ongoing changes to several DMT product labels [16]. It follows that a more accurate benefit–risk assessment is possible for a DMT scrutinized by postmarketing surveillance than for a DMT that has completed Phase III clinical development, but has yet to undergo safety evaluation in a large patient population over a protracted period of drug exposure. For instance, a prospective descriptive study of patients with MS between 1995 and 2006 found an increased malignancy risk with the sequencing of multiple immunomodulatory and immunosuppressant therapies, and also with the number of immunosuppressant courses [56].

Beta interferons, peginterferon beta-1a, and glatiramer acetate

The mechanism(s) of action of the beta interferons are not yet fully established, although these therapies have been available since the 1990s. All beta interferons are known to exert autocrine and paracrine actions via activation of the interferon receptor on leukocytes (Table 2). Production of proinflammatory cytokines is reduced, and production of anti-inflammatory cytokines is induced [18]. Attachment of a polyethylene glycol side chain to the parent interferon beta-1a molecule yields peginterferon beta-1a, which, when administered subcutaneously, has a longer half-life, higher systemic exposure, and lower immunogenicity potential than intramuscular interferon beta-1a [57]. Glatiramer acetate, a synthetic polymer of four amino acids (l-glutamate, l-lysine, l-alanine, and l-tyrosine), is a mimetic for the MS autoantigen myelin basic protein (MBP), and thus competes with MBP antigens for binding to class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC II) [58]. With formation of the MBP antigen/MHC II complex impeded by glatiramer, helper T cells have less opportunity for activation and potential to destroy myelin [58]. In addition, glatiramer binding to MHC II inhibits the interaction of MHC II with CD4+ molecules located on the surface of helper T cells (Th1 and Th2). Consequently, there is reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines (interferon gamma) by Th1 cells, increased production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin 10) by Th2 cells (promoting a less inflammatory state), and induction of antigen-specific expansion of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells [58, 59].

The effects of beta interferons and glatiramer acetate on the immune system likely only endure for as long as a patient is exposed to therapeutic drug concentrations (i.e., less than five times the elimination half-life; Table 2). The safety profiles of the beta interferons and glatiramer acetate are well established (Table 5).

Dimethyl fumarate

Following oral administration, dimethyl fumarate is rapidly metabolized to its active metabolite monomethyl fumarate, which is primarily responsible for its efficacy in MS [60, 61]. Similar to other fumarate derivatives, administration of dimethyl fumarate activates nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2, resulting in differential effects involving antioxidant responses (Table 2) [60]. It is likely that dimethyl fumarate has several additional immunomodulatory effects underpinning its efficacy in MS, including directing the immune response away from Th1 [62].

Integrated analyses of patient-level data (N = 2470) from Phase IIb, Phase III, and long-term extension studies of dimethyl fumarate showed that mean absolute lymphocyte count decreased by 30%, but generally remained above the lower limit of normal during the first year of treatment, before stabilizing [63]. Separate observational data indicated that the dynamics of the absolute lymphocyte count generally correlate with CD4+ and CD8+ counts [64], with the reduction of CD8+ T cells greater than that of CD4+ T cells (−55 vs. −39%) reflected in a 36% increase in the CD4/CD8 ratio [65]. In patients without severe lymphopenia (i.e., <0.5 × 109 cells/L), there is evidence of improvement in lymphocyte counts following discontinuation of dimethyl fumarate, but full restoration takes >4 weeks [63, 66, 67]. For patients who become severely lymphopenic on dimethyl fumarate, lymphocyte counts may take a long time to recover [66]; this delay in lymphocyte recovery may complicate the switch to a subsequent DMT with myelosuppressive effects. Six percent of patients experienced lymphocyte counts <0.5 × 109/L (grade ≥3 lymphopenia) in placebo-controlled trials [67]. The risk of developing moderate to severe lymphopenia while on dimethyl fumarate may be increased by the following: increasing age, lower baseline absolute lymphocyte count, and recent natalizumab exposure (there is a greater percentage reduction in absolute lymphocyte count due to the lymphocytosis induced by prior natalizumab) [64, 66]. Although the risk may be slightly different in patients of older age or with lower baseline absolute lymphocyte count, all patients remain at a small risk of lymphopenia. Based on 7250 cumulative patient-years of exposure, the overall incidence of serious infections was low, and there was no apparent correlation between the incidence of infection and grade of lymphopenia [63].

Of >230,000 patients treated with dimethyl fumarate globally in the 3 years following commercial availability (representing >330,000 patient-years), there have been five cases of PML in the setting of moderate to severe prolonged lymphopenia (absolute lymphocyte count <0.8 × 109/L), a rare opportunistic brain infection caused by John Cunningham (JC) virus that is normally harmless in immunocompetent hosts [25, 68]. There are established risk stratification and mitigation strategies for patients on dimethyl fumarate in light of its safety profile. In the US, complete blood counts at baseline and every 6 months thereafter are mandatory to identify patients who may have developed severe prolonged lymphopenia [67]. In Europe, a baseline MRI also should be performed within 3 months of initiating therapy [69].

Teriflunomide

Teriflunomide is the active metabolite of leflunomide, which has anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, and immunosuppressive properties [70]. Teriflunomide selectively and reversibly inhibits dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, a key mitochondrial enzyme in the de novo pyrimidine synthesis pathway, resulting in lymphocyte cell cycle impairment, without causing cell death [58]. Teriflunomide reduces neutrophils (during the first 6 weeks) and lymphocytes (during the first 3 months) by ~15%, although mean counts remain in the normal range [71]. Teriflunomide also inhibits protein tyrosine kinases, leading to decreased T cell proliferation, and a shift in the cytokine profile to a more anti-inflammatory cytokine milieu [58].

The long elimination half-life (18–19 days) of teriflunomide [72], due in part to its extensive enterohepatic recirculation, means that it can take approximately 8 months for the body to eliminate the drug, although plasma drug concentrations can still be detected up to 2 years after administration of the last dose [72]. If a rapid switch to another DMT is required, then an accelerated elimination procedure with either administration of cholestyramine or activated charcoal for 11 days should be considered [72], including in patients with cytopenia. Both elimination regimens result in a 98% decrease in plasma teriflunomide concentrations (i.e., <0.02 mg/L) [72, 73].

No new safety signals beyond those detected in individual trials (and summarized in Table 5) were identified with treatment duration exceeding 12 years and a cumulative exposure to teriflunomide exceeding 6800 patient-years [71]. Nonfebrile neutropenia and lymphopenia were reported in 5.9% and 0.5% of patients receiving teriflunomide over 1500 patient-years of cumulative treatment exposure, respectively [71]; no association between neutrophil count decrease and infection occurrence was detected [71]. Cases of thrombocytopenia, including rare cases with platelet counts <50,000/mm3, have been reported in the postmarketing setting [74]. Serious skin reactions, including severe generalized major skin AEs [Stevens–Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell’s syndrome)] have been reported [74]. Teriflunomide is causally linked to one fatal case of toxic epidermal necrolysis [75], but has not been linked with PML. Complete blood count, tuberculin skin tests (to identify latent tuberculosis infection), liver function tests, and blood pressure measurements are required at baseline; liver function and blood pressure also should be monitored monthly for the first 6 months and then regularly thereafter with continued treatment [72].

Fingolimod

Fingolimod is phosphorylated following oral administration to fingolimod phosphate, a mimetic for the naturally occurring extracellular lipid sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) [76]. S1P is an extracellular signaling molecule that regulates trafficking of many types of T and B cells from the lymph nodes to the blood (Table 2) [58]. Blood T cell levels decrease when S1P receptors are activated, as naive T cells are sequestered within secondary lymphoid organs after their egress from peripheral blood [58]. Lymphopenia is an expected pharmacodynamic effect of fingolimod due to the increased movement of CCR7+ lymphocytes into secondary lymphoid organs [77]. Fingolimod induces a rapid and reversible dose-dependent reduction in peripheral lymphocyte count to 20–30% of baseline values [13]. Peripheral lymphocyte reconstitution following fingolimod discontinuation occurs over 1–2 months [13], but this period may be extended with fingolimod use exceeding 1 year [78]. Rarely, an abrupt rise in lymphocyte count occurs during the fingolimod postwithdrawal period (immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome), putting patients at risk for MS disease reactivation [79].

Cases of PML have occurred in patients with MS receiving fingolimod in the postmarketing setting who had not been previously treated with natalizumab nor who were taking immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory medications concomitantly [13]. In addition, affected patients had no other ongoing identified systemic medical conditions resulting in compromised immune system function [13]. For this reason, fingolimod should be withheld at the first sign or symptom suggestive of PML [13]. In addition, patients with signs and symptoms consistent with other opportunistic pathogens, including herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2, varicella zoster virus, cryptococci, and atypical mycobacteria, should undergo prompt diagnostic evaluation and appropriate treatment [13, 80].

Fingolimod phosphate acts on four of the five known S1P receptor subtypes expressed on a variety of cell types, including endothelial cells, lymphocytes, smooth muscle and cardiac myocytes, and neural cells [76]. Consequently, fingolimod administration elicits significant off-target pharmacology, resulting in rare but serious AEs (Table 5) [16]. For these reasons, in Europe, fingolimod is considered a second-line DMT following failure of interferon beta or glatiramer acetate, or a first-line agent for patients with highly active disease [12]. No such restrictions are placed on its use in the US, although numerous changes have been made to the warnings and precautions listed in the fingolimod product label to guide proper use (Table 5) [80]. Hence, patient selection and monitoring is of paramount importance to increase the likelihood that the benefits of fingolimod outweigh its risks. Baseline laboratory tests include complete blood count, liver enzymes, pregnancy test, and varicella zoster virus status [12, 13]. Tests that are required before dosing, during, and/or posttreatment with fingolimod include cardiac and blood pressure monitoring, complete blood counts, and examination of the fundus for macular edema [13]. Monitoring for signs of infection and suspicious skin lesions in case of basal cell carcinoma also should be conducted, as per the fingolimod product label [13]. Case reports of severe disease reactivation following fingolimod withdrawal [46,47,48] also must be considered when treating patients with highly active disease and in women who wish to become pregnant (in whom it is advised to continue therapy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus) [12].

Daclizumab beta

Daclizumab beta is a humanized monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of RMS as a monthly subcutaneous self-injectable [81,82,83]. Daclizumab beta works in the periphery by binding CD25 (alpha subunit of the high-affinity interleukin 2 receptor mostly expressed on activated T cells) to modulate interleukin 2 signaling (Table 2) [84,85,86,87]. Blockade of CD25 by daclizumab beta limits interleukin 2 consumption by activated T cells and facilitates cells that express the intermediate-affinity interleukin 2 receptor [i.e., natural killer (NK) cells and precursors of innate lymphoid cells] to receive more interleukin 2 signal, as this receptor does not feature CD25 [88, 89]. Consequently, there is a substantial expansion of immunoregulatory CD56bright NK cells that penetrate the blood–brain barrier and eliminate important mediators of MS immunopathology, activated T cells, leaving resting T cells intact (Table 2) [84, 86, 90, 91].

The pharmacodynamic effects of daclizumab beta are sustained in patients with relapsing–remitting MS, as evidenced by a fivefold expansion of CD56bright NK cell levels that plateau by the end of the first year of treatment [92, 93]. Modest 10% reductions in circulating total lymphocytes, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and B cells were observed in patients with MS after 1 year of daclizumab beta 150 mg treatment, and regulatory T cell levels were reduced by approximately 50% after 8 weeks [92,93,94]. The remaining regulatory T cells are functionally active, as evidenced by stable cytokine production, maintained active cell cycling, and retention of a regulatory T cell-specific demethylated region in the FOXP3 promoter, albeit with a significant decrease in CD25 expression [94]. The effects of daclizumab beta are reversible; after treatment cessation, total lymphocyte counts return to baseline levels within 12 weeks, and CD56bright NK cell and regulatory T cell counts return to baseline levels within 24 weeks [93, 95]. There was no apparent impact of antidrug antibodies or neutralizing antibodies on the pharmacodynamics, efficacy, or safety of daclizumab beta [82, 96].

The safety profile of daclizumab beta was determined over a 5-year period and was consistent with that from the pivotal Phase III trial (Table 5) [97]. Given the recent approvals for daclizumab beta, there are only limited data from real-world use, although the product label provides specific warnings regarding hepatic injury—elevations of serum transaminases and serious events, including fatal cases of autoimmune hepatitis and liver failure—and other immune-mediated disorders (including skin reactions, lymphadenopathy, and noninfectious colitis) as well as depression, infections, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, gastrointestinal AEs, and lymphopenia [81, 82]. These warnings are based on safety and tolerability information from an integrated analysis of six clinical studies (primarily randomized controlled trials and their extensions) encompassing 2236 patients with 5214 patient-years of daclizumab beta exposure [98]. Although this database was not large enough to detect rare events, the analysis did show that daclizumab beta had an acceptable safety profile without evidence of cumulative toxicity [98]. Daclizumab beta should be discontinued in cases of significant transaminase elevation [i.e., alanine transaminase (ALT) or aspartate transaminase (AST) >5 × the upper limit of normal (ULN) only; or total bilirubin greater >2 × ULN; or ALT or AST ≥3 but <5 × ULN and total bilirubin >1.5 and <2 × ULN] [82]. Discontinuing daclizumab beta should be considered if severe depression or suicidal ideation occurs [81, 82]. If serious infection develops, daclizumab beta should be withheld until the episode resolves [81, 82].

Alemtuzumab

The humanized monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab targets the extracellular glycoprotein CD52, resulting in antibody-dependent cytolysis and complement-mediated lysis of T and B lymphocytes, monocytes, NK cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells (Table 2) [99, 100]. Alemtuzumab elicits rapid, profound, and prolonged B and T cell lymphopenia followed by a reconstituted immune system different in composition from that before treatment, which may rationalize its long-term efficacy, given patients only receive two medication cycles that are 1 year apart (Table 3) [99, 100]. It can take ~8 months for B cells and up to 3 years for T cell subsets to recover to the lower limits of the normal range after a single course of alemtuzumab, and T cells may not recover fully to baseline values [101]. It is worth noting that B cell recovery was rapid in one study; levels of ‘mature naive’ B cells (CD19 and CD23 positive but CD27 negative) returned to baseline by 3 months and rose to 165% of baseline values by 12 months after the first course of alemtuzumab treatment [102]. Conversely, CD27-positive memory B cell recovery was slow, reaching only 25% of baseline levels by month 12 [102]. The immunosuppressive effects of alemtuzumab on CD4+ T cell subsets lasted for up to 4 years in 29 patients who participated in CARE-MS I and CARE-MS II [103]. Differential lymphocyte reconstitution after alemtuzumab treatment may be a biomarker for MS relapse, as patients with active disease showed an accelerated recovery of CD4+ cells (p = 0.001), with a difference in absolute CD4+ counts at 24 months (p = 0.009), while CD4+ counts <388 × 106 cells/mL predicted MRI stability [104]. Anti-alemtuzumab antibodies reduce plasma alemtuzumab concentrations during course 2 but not course 1, although they do not appear to affect clinical outcomes, total lymphocyte count, or AEs [100]. Alemtuzumab induces long-term immunodepleting effects, which must be considered when planning subsequent therapies for maintenance treatment or if a patient does not respond adequately. There are no data on sequencing therapies after alemtuzumab use to guide the clinician, who must, therefore, rely on intensive patient monitoring to individualize care.

Although the advantages of long-lasting efficacy and extremely high patient adherence are positive attributes of alemtuzumab, Table 5 shows that this DMT is associated with several serious AEs that may arise years after starting treatment and are, therefore, not reflective of alemtuzumab’s pharmacokinetic profile (elimination half-life, 2 weeks) [100]. Alemtuzumab is usually reserved for patients with unfavorable prognostic indicators because it is difficult to reconcile its superior efficacy over interferon beta with exposure to serious AEs in patients with less severe disease. Even in patients with highly active disease, diligent patient selection and strict adherence to risk monitoring programs is required. The alemtuzumab product label recommends regular laboratory monitoring up to 4 years after the last alemtuzumab dose (and beyond if warranted) for the detection of secondary autoimmune conditions (e.g., immune thrombocytopenia, antiglomerular basement membrane disease, and thyroid disorders) [100]. Laboratory testing includes differential blood count, serum creatinine, and urine analysis before administration and monthly thereafter [100]. Pretreatment thyroid-stimulating hormone level is mandatory and requires rechecking every 3 months until 4 years after the last infusion [100]. Patients with active or uncontrolled infections are not candidates for therapy [100]. Prophylactic oral acyclovir should be taken until CD4+ count is >200 cell/mm3 to reduce the risk for herpes infections [100, 105].

Natalizumab

Natalizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to the integrin molecule very late activation antigen 4 (α4β1), a glycoprotein surface molecule found on all leukocytes except neutrophils (Table 2) [58]. Blockade of α4β1 prevents adhesion of leukocytes to vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, a protein expressed on the surface of vascular endothelial cells in the brain and spinal cord, and thus blocks entry of leukocytes into the central nervous system across the blood–brain barrier [58]. Natalizumab increases the number of circulating leukocytes (due to inhibition of transmigration out of the vascular space), but does not affect the absolute count of circulating neutrophils [20].

Natalizumab has an elimination half-life of 11 days [20], although plasma natalizumab concentrations can be reduced by 92% within 1 week of plasma exchange sessions to treat PML if required [106]. The reversibility of natalizumab’s pharmacologic effects on peripheral immune cells is evident starting at weeks 8–12, with levels returning to those observed or expected in non-natalizumab patients by 16–20 weeks after the last natalizumab dose [107]. This is consistent with the reduction in plasma natalizumab concentrations to below the limit of detection by 16 weeks postdose [107]. Lymphocyte counts remain within the normal range at all times both for patients receiving natalizumab and for those who have stopped natalizumab treatment [107]. Patients who develop anti-natalizumab antibodies are more likely to have hypersensitivity reactions during drug administration [20].

An intensive risk stratification program is in place to help prescribers weigh the clear efficacy benefits of natalizumab against the development of PML [19, 20]. Three main factors drive the risk of developing PML in patients undergoing natalizumab therapy: (1) therapy ≥24 months; (2) previous use of immunosuppressant treatment; and (3) JC virus antibody positivity [108]. The anti-JC virus antibody index value and duration of natalizumab treatment are two key factors that enable clinicians and JC virus-positive immunosuppressant-naive patients with MS to make informed treatment and monitoring decisions [109,110,111].

Natalizumab withdrawal often leads to an MS relapse and return of inflammatory disease activity on MRI [49,50,51,52,53]. Younger patients (<40 years of age) were 3.8-fold more likely to have increased MRI activity during 24 weeks of natalizumab treatment interruption, as were those with one to five Gd+ lesions (2.7-fold increase) and >five Gd+ lesions (6.2-fold) before natalizumab initiation (vs. no lesions) [52]. Initiating interferon beta within 30 days postnatalizumab dosing in patients who had been free of disease activity [112], or initiating fingolimod ~4 months postnatalizumab dosing in patients with stable Expanded Disability Status Scale scores [113], was associated with clinical and radiologic disease recurrence. A therapeutic gap of no more than 3 months between discontinuing natalizumab and initiating fingolimod appears to minimize the risk of relapse [113]. Switching from natalizumab to alemtuzumab (n = 16) [114] or off-label rituximab (n = 114 [115] and n = 118 [116]) may be a feasible option to maintain disease control, including in those at high risk of PML. It is currently unknown if the switch-to therapy selection impacts the risk of PML in this context. Data on treatment selection after a PML event on natalizumab are limited, but there are reports of successful use of both dimethyl fumarate and fingolimod in this situation [117].

Ocrelizumab

Ocrelizumab is a B cell-directed cytolytic monoclonal antibody with a humanized immunoglobulin G1 tail indicated for the treatment of patients with relapsing or primary progressive forms of MS as a twice-yearly intravenous infusion [118]. This recombinant monoclonal antibody binds to a different but overlapping CD20 epitope expressed on B cells to rituximab [119]. By binding to the cell surface antigen CD20 present on pre-B and mature B lymphocytes, it is believed that ocrelizumab induces antibody-dependent cellular cytolysis, complement-mediated lysis, and/or apoptosis via crosslinking membrane CD20 on the target cell surface [118, 119].

Assays for CD19+ B cells are used as a surrogate for B cell counts because ocrelizumab interferes with the CD20 assay. As such, ocrelizumab reduces circulating CD19+ B cell counts 14 days postinfusion to negligible levels [118]. In clinical studies, B cell counts rose to above the lower limit of normal or above baseline counts between infusions of ocrelizumab at least once in 0.3–4.1% of patients [118]. Median (range) time for B cell counts to return to either baseline or the lower limit of normal was 72 (27–175) weeks after the last ocrelizumab infusion (Table 2) [118]. Within 2.5 years after the last infusion, B cell counts rose to either baseline or the lower limit of normal in 90% of patients [118].

Treatment-emergent ocrelizumab AEs observed in a pooled analysis of the two identical 96-week Phase III OPERA trials included infections, infusion-related reactions, and an incidence rate of first neoplasm of 0.40 per 100 patient-years of exposure, based on data from 6467 patient-years of exposure (Table 5) [120]. The ocrelizumab prescribing information states that breast cancer occurred in 6 of 781 females treated with ocrelizumab versus none of 668 females treated with subcutaneous interferon beta-1a or placebo [118]. Hence, patients receiving ocrelizumab should be encouraged to follow standard breast cancer screening guidelines. The long-term effects and risks of B cell depletion on malignancy risk will remain uncertain until long-term real-world follow-up data are available, and may currently be underrecognized. As with alemtuzumab, long-term B cell depletion with ocrelizumab may limit subsequent treatment options. For instance, initiation of a later-line therapy while B cell levels remain depleted may result in cumulative, and presently undocumented, effects on immune system function. The appropriate timing for initiating other DMTs after a patient has received ocrelizumab should be considered by the physician. The immunogenicity of ocrelizumab appears low, based on the incidence of formation of treatment-emergent antidrug antibodies (~0.4%) [120].

Balancing benefits versus risks: information for patients and physicians

Patient-related factors are key multifactorial inputs that influence response to DMTs, and how much a DMT is used in clinical practice. Selecting the treatment best suited for an individual at each phase of the disease is challenging, but can be facilitated by establishing a concordant relationship with the patient and their significant other (support partner). A key concept that may be disagreed upon in patients who feel relatively healthy is the value placed on future health benefits versus the present-day inconvenience of administering DMTs (e.g., tolerability, acquisition cost) and the safety profile of the DMT. Patient discussions provide an opportunity for the neurologist to relate the goals of the DMT to the patient, namely to safely reduce relapses and incidence and severity of new MRI lesions, thereby reducing the risk for permanent disability. Educating the patient about both the immediate symptomatic and long-term pathophysiological aspects of MS can facilitate the progression to a shared agreement about therapeutic goals and the level of risk patients and their partners are willing to assume. The neurologist can then help guide the patient regarding the long-term goals, general principles of sequencing DMTs, and the appropriate DMT treatment, rather than assessing their views and discussing details such as relative efficacy rates and disability rating scales.

There is some evidence of an effect on delaying disability progression with fingolimod, daclizumab beta, alemtuzumab, and natalizumab versus interferon beta or glatiramer acetate (Table 3). An appreciation of the treatment regimens from the patient’s perspective often reveals that their agendas and priorities may not match those of their neurologist, who should be guided by evidence-based medicine. The risk of the disease, which may be hard to precisely define, is another important part of the benefit–risk discussion in shared decision making. Hence, it is important to convey the advantages and disadvantages of each DMT to the patients based on their RMS history and likelihood/unpredictability of future disease-related events.

PML has been associated with several DMTs for MS, and one of the greatest needs in understanding the benefit–risk of a DMT is to quantify the likelihood of PML after the first DMT and also after two or more DMTs have been added in sequence. It is important to note that PML risk differs by therapy. A logical classification for stratifying DMT PML risk has been proposed, with natalizumab having the highest PML risk (incidence 1/100–1/1000), followed by far lesser degrees of risk for fingolimod (incidence 1/18,000) and dimethyl fumarate (incidence ~1/50,000) [26]. PML risk for other DMTs is very low or uncertain [26]. It is currently unknown whether or how the sequencing of these therapies might impact the overall PML risk of each patient.

The immunization status of the patient also is important because of interactions between some DMTs and vaccine response. The National Multiple Sclerosis Society does not recommend use of live vaccinations in people with MS [121], and respective product labels for teriflunomide, fingolimod, daclizumab beta, or alemtuzumab advise avoiding use of live attenuated vaccines during and for prespecified time periods after stopping therapy [13, 72, 82, 100]. No product-specific information is available on the effects of vaccination in patients receiving peginterferon beta-1a, glatiramer acetate, dimethyl fumarate, and natalizumab. Therefore, complete or partial prevention of infection by influenza, tuberculosis, varicella zoster virus, and hepatitis A and B may be considered by vaccination before starting immunomodulatory therapy. Availability of non-live vaccines, such as the herpes zoster subunit vaccine (HZ/su) containing recombinant varicella zoster virus glycoprotein E and the AS01B adjuvant system [122], may represent a welcome and more flexible addition to efforts to prevent infection in patients with MS receiving DMTs.

For elderly patients, a potential benefit–risk consideration for the DMTs dimethyl fumarate, teriflunomide, fingolimod, alemtuzumab, and ocrelizumab is their variable effect on lymphocyte counts, which occur as a consequence of their on- or off-target pharmacology (Table 2). In elderly patients, age-related immunosenescence, characterized by diminished levels and functionalities of B and T lymphocytes, may lead to a theoretically greater likelihood of lymphopenia with these DMTs [123]. One also could hypothesize that elderly patients would be less likely to experience breakthrough MS activity for the same reason. Hence, older age affects the benefit–risk ratio of DMTs and acts as a prompt for neurologists to consider hematologic monitoring when making prescribing decisions.

Progress toward development of pharmacogenetics- and biomarker-based approaches to individualize treatments according to patient and DMT characteristics is in its infancy [124, 125]. In the meantime, other factors on which to base these decisions include patient preferences, lifestyle and beliefs, comorbidities and concomitant medications, immunization status, family planning, and age. The first three factors have a profound influence on adherence to medication; poor adherence predisposes the patient to suboptimal clinical, neuroradiologic, health-related quality of life, and pharmacoeconomic outcomes [126,127,128,129,130,131].

Conclusions

The topics raised in our review also are emphasized in initial draft guidelines for the treatment of MS drawn up by the European Academy of Neurology, European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, and American Academy of Neurology [132, 133]. Because both documents are highly data driven, there is no recommendation provided for selecting one DMT over another. Instead, the appropriate choice of DMT is the one that the practicing neurologist rationalizes will provide the level of efficacy warranted by the recent disease activity, balanced by patient safety and preferences.

The long-term immunologic and safety risks of sequencing multiple therapies are still unknown. Prescribing DMTs in RMS depends on a thorough benefit–risk analysis, which is inconclusive if the patient’s characteristics are not reflective of clinical trial populations, and if the long-term effects of DMT in the clinical practice setting are unknown. Prospective industry-sponsored switching studies, patient registries, and robust analysis of real-world data are needed to collect data tailored to the therapeutic agent and various patient scenarios. Until such evidence-based medical information is available, decisions on sequencing DMTs for RMS will depend heavily on the clinical acumen of the neurologist. In the meantime, sequencing the most appropriate therapies for patients with RMS is usually determined by a combination of factors such as disease activity, patient-related factors, and drug-related factors (e.g., pharmacodynamic profile).

Treatment should be selected to address the immediate clinical issue, and to keep alternative therapeutic options available for later-line therapies. This consideration is particularly important early on in the disease course and even more relevant in today’s therapeutic landscape, which includes DMT options with potentially long-lasting effects on the immune system that can persist for months or even years following discontinuation of therapy. Patients should be made aware of these issues so that a shared care decision can be reached, which is driven by matching the level of risk a patient is willing to accept with their prognostic factors.

Change history

23 October 2017

Unfortunately, the online published article has errors in Table 2. The Peginterferon is listed as IM, when it should be SC.

References

Compston A, Coles A (2008) Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 372:1502–1517. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7

Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG (2000) Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 343:938–952. doi:10.1056/NEJM200009283431307

Barten LJ, Allington DR, Procacci KA, Rivey MP (2010) New approaches in the management of multiple sclerosis. Drug Des Devel Ther 4:343–366. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S9331

Muñoz-Culla M, Irizar H, Otaegui D (2013) The genetics of multiple sclerosis: review of current and emerging candidates. Appl Clin Genet 6:63–73. doi:10.2147/TACG.S29107

Sawcer S, Hellenthal G, Pirinen M, Spencer CC, Patsopoulos NA, Moutsianas L, International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 et al (2011) Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature 476:214–219. doi:10.1038/nature10251

Lucchinetti C, Bruck W, Parisi J, Scheithauer B, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H (2000) Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis lesions: implications for the pathogenesis of demyelination. Ann Neurol 47:707–717. doi:10.1002/1531-8249(200006)47:6<707:AID-ANA3>3.0.CO;2-Q

Dos Passos GR, Sato DK, Becker J, Fujihara K (2016) Th17 cells pathways in multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: pathophysiological and therapeutic implications. Mediators Inflamm 2016:5314541. doi:10.1155/2016/5314541

Lovett-Racke AE, Yang Y, Racke MK (2011) Th1 versus Th17: are T cell cytokines relevant in multiple sclerosis? Biochim Biophys Acta 1812:246–251. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.05.012

Koch MW, Metz LM, Kovalchuk O (2013) Epigenetic changes in patients with multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 9:35–43. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2012.226

Disanto G, Berlanga AJ, Handel AE, Para AE, Burrell AM, Fries A et al (2010) Heterogeneity in multiple sclerosis: scratching the surface of a complex disease. Autoimmune Dis 2011:932351. doi:10.4061/2011/932351

Lublin FD, Reingold SC, National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis (1996) Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. Neurology 46:907–911. doi:10.1212/WNL.46.4.907

European Medicines Agency (2015) Gilenya 0.5 mg hard capsules [summary of product characteristics]. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002202/WC500104528.pdf. Accessed 15 April 2016

Novartis (2016) Gilenya [prescribing information]. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, USA

Mikol DD, Barkhof F, Chang P, Coyle PK, Jeffery DR, Schwid SR, REGARD study group et al (2008) Comparison of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a with glatiramer acetate in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (the REbif vs Glatiramer Acetate in Relapsing MS Disease [REGARD] study): a multicentre, randomised, parallel, open-label trial. Lancet Neurol 7:903–914. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70200-X

Limmroth V, Malessa R, Zettl UK, Koehler J, Japp G, Haller P, QUASIMS Study Group et al (2007) Quality Assessment in Multiple Sclerosis Therapy (QUASIMS): a comparison of interferon beta therapies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 254:67–77. doi:10.1007/s00415-006-0281-1

Yadav V, Bourdette D (2012) New disease-modifying therapies and new challenges for MS. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 12:489–491. doi:10.1007/s11910-012-0295-2

Goodin DS, Ebers GC, Cutter G, Cook SD, O’Donnell T, Reder AT et al (2012) Cause of death in MS: long-term follow-up of a randomised cohort, 21 years after the start of the pivotal IFNbeta-1b study. BMJ Open 30:2. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001972

Du Pasquier RA, Pinschewer DD, Merkler D (2014) Immunological mechanism of action and clinical profile of disease-modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs 28:535–558. doi:10.1007/s40263-014-0160-8

European Medicines Agency (2006) Tysabri 300 mg concentrate for solution for infusion [summary of product characteristics]. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000603/WC500044686.pdf. Accessed 15 April 2016

Biogen (2016) Tysabri [prescribing information]. Biogen, Cambridge, MA, USA

Spelman T, Kalincik T, Jokubaitis V, Zhang A, Pellegrini F, Wiendl H et al (2016) Comparative efficacy of first-line natalizumab vs IFN-β or glatiramer acetate in relapsing MS. Neurol Clin Pract 6:102–115. doi:10.1212/cpj.0000000000000227

Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (2017) Disease-modifying therapies for relapsing-remitting and primary-progressive multiple sclerosis: effectiveness and value. https://icer-review.org/. Accessed 4 July 2017

European Medicines Agency (2016) Conditions or restrictions with regard to the safe and effective use of the medicinal product to be implemented by the member states. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Conditions_imposed_on_member_states_for_safe_and_effective_use/human/000603/WC500044687.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2016

Ziemssen T, De Stefano N, Pia Sormani M, Van Wijmeersch B, Wiendl H, Kieseier BC (2015) Optimizing therapy early in multiple sclerosis: an evidence-based view. Mult Scler Relat Disord 4:460–469. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2015.07.007

Van Schependom J, Gielen J, Laton J, Nagels G (2016) Assessing PML risk under immunotherapy: if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Mult Scler 22:389–392. doi:10.1177/1352458515596458

Berger JR (2017) Classifying PML risk with disease modifying therapies. Mult Scler Relat Disord 12:59–63. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2017.01.006

Giovannoni G, Butzkueven H, Dhib-Jalbut S, Hobart J, Kobelt G, Pepper G et al (2016) Brain health: time matters in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 9(suppl 1):S5–S48. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2016.07.003

Rio J, Castillo J, Rovira A, Tintore M, Sastre-Garriga J, Horga A et al (2009) Measures in the first year of therapy predict the response to interferon beta in MS. Mult Scler 15:848–853. doi:10.1177/1352458509104591

Sormani MP, Rio J, Tintore M, Signori A, Li D, Cornelisse P et al (2013) Scoring treatment response in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 19:605–612. doi:10.1177/1352458512460605

Freedman MS, Selchen D, Arnold DL, Prat A, Banwell B, Yeung M, Canadian Multiple Sclerosis Working Group et al (2013) Treatment optimization in MS: Canadian MS Working Group updated recommendations. Can J Neurol Sci 40:307–323

Stangel M, Penner IK, Kallmann BA, Lukas C, Kieseier BC (2015) Towards the implementation of ‘no evidence of disease activity’ in multiple sclerosis treatment: the multiple sclerosis decision model. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 8:3–13. doi:10.1177/1756285614560733

Freedman MS, Cohen B, Dhib-Jalbut S, Jeffery D, Reder AT, Sandberg-Wollheim M, Weinstock-Guttman B (2009) Recognizing and treating suboptimally controlled multiple sclerosis: steps toward regaining command. Curr Med Res Opin 25:2459–2470. doi:10.1185/03007990903158364

Gajofatto A, Benedetti MD (2015) Treatment strategies for multiple sclerosis: when to start, when to change, when to stop? World J Clin Cases 3:545–555. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v3.i7.545

Ingwersen J, Aktas O, Hartung HP (2016) Advances in and algorithms for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics 13:47–57. doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0412-4

Edan G, Le Page E (2013) Induction therapy for patients with multiple sclerosis: why? When? How? CNS Drugs 27:403–409. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0065-y

Giovannoni G, Turner B, Gnanapavan S, Offiah C, Schmierer K, Marta M (2015) Is it time to target no evident disease activity (NEDA) in multiple sclerosis? Mult Scler Relat Disord 4:329–333. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2015.04.006

Coles AJ, Fox E, Vladic A, Gazda SK, Brinar V, Selmaj KW et al (2012) Alemtuzumab more effective than interferon ß-1a at 5-year follow-up of CAMMS223 clinical trial. Neurology 78:1069–1078. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824e8ee7

Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, Rice GP, Muraro PA, Daumer M, Ebers GC (2010) The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain 133(Pt 7):1914–1929. doi:10.1093/brain/awq118

Klineova S, Nicholas J, Walker A (2012) Response to disease modifying therapies in African Americans with multiple sclerosis. Ethn Dis 22:221–225

Rinaldi L, Perini P, Calabrese M, Gallo P (2009) Cyclophosphamide as second-line therapy in multiple sclerosis: benefits and risks. Neurol Sci 30(suppl 2):S171–S173. doi:10.1007/s10072-009-0145-4

Vollmer T, Panitch H, Bar-Or A, Dunn J, Freedman MS, Gazda SK et al (2008) Glatiramer acetate after induction therapy with mitoxantrone in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 14:663–670. doi:10.1177/1352458507085759

Arnold DL, Campagnolo D, Panitch H, Bar-Or A, Dunn J, Freedman MS et al (2008) Glatiramer acetate after mitoxantrone induction improves MRI markers of lesion volume and permanent tissue injury in MS. J Neurol 255:1473–1478. doi:10.1007/s00415-008-0911-x

Atkins HL, Bowman M, Allan D, Anstee G, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A et al (2016) Immunoablation and autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for aggressive multiple sclerosis: a multicentre single-group phase 2 trial. Lancet 388:576–585. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30169-6

Mancardi GL, Sormani MP, Gualandi F, Saiz A, Carreras E, Merelli E, ASTIMS Haemato-Neurological Collaborative Group on behalf of the Autoimmune Disease Working Party (ADWP) of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) et al (2015) Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis: a phase II trial. Neurology 84:981–988. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001329

Nash RA, Hutton GJ, Racke MK, Popat U, Devine SM, Griffith LM et al (2015) High-dose immunosuppressive therapy and autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (HALT-MS): a 3-year interim report. JAMA Neurol 72:159–169. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3780

Berger B, Baumgartner A, Rauer S, Mader I, Luetzen N, Farenkopf U, Stich O (2015) Severe disease reactivation in four patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis after fingolimod cessation. J Neuroimmunol 282:118–122. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.03.022

Siva A, Uygunoglu U, Tutunca M, Altintas A, Saip S (2016) Rebound of disease activity after fingolimod discontinuation: report of six cases. Neurology 86(16 suppl):P2.081

Hatcher SE, Waubant E, Nourbakhsh B, Crabtree-Hartman E, Graves JS (2016) Rebound syndrome in patients with multiple sclerosis after cessation of fingolimod treatment. JAMA Neurol 73:790–794. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0826

Clerico M, Schiavetti I, De Mercanti SF, Piazza F, Gned D, Brescia Morra V et al (2014) Treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis after 24 doses of natalizumab: evidence from an Italian spontaneous, prospective, and observational study (the TY-STOP Study). JAMA Neurol 71:954–960. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1200

Fox RJ, Cree BA, De Sèze J, Gold R, Hartung HP, Jeffery D, RESTORE et al (2014) MS disease activity in RESTORE: a randomized 24-week natalizumab treatment interruption study. Neurology 82:1491–1498. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000355

Giovannoni G, Naismith RT (2014) Natalizumab to fingolimod washout in patients at risk of PML: when good intentions yield bad outcomes. Neurology 82:1196–1197. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000296

Kaufman M, Cree BA, De Sèze J, Fox RJ, Gold R, Hartung HP et al (2015) Radiologic MS disease activity during natalizumab treatment interruption: findings from RESTORE. J Neurol 262:326–336. doi:10.1007/s00415-014-7558-6

Kerbrat A, Le Page E, Leray E, Anani T, Coustans M, Desormeaux C et al (2011) Natalizumab and drug holiday in clinical practice: an observational study in very active relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol Sci 308:98–102. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.043

Giovannoni G, Radue EW, Havrdova E, Riester K, Greenberg S, Mehta L, Elkins J (2014) Effect of daclizumab high-yield process in patients with highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 261:316–323. doi:10.1007/s00415-013-7196-4

Giovannoni G, Gold R, Selmaj K, Havrdova E, Montalban X, Radue EW, SELECTION Study Investigators et al (2014) Daclizumab high-yield process in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (SELECTION): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind extension trial. Lancet Neurol 13:472–481. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70039-0

Lebrun C, Debouverie M, Vermersch P, Clavelou P, Rumbach L, de Seze J et al (2008) Cancer risk and impact of disease-modifying treatments in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 14:399–405. doi:10.1177/1352458507083625

Hu X, Miller L, Richman S, Hitchman S, Glick G, Liu S et al (2012) A novel PEGylated interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis: safety, pharmacology, and biology. J Clin Pharmacol 52:798–808. doi:10.1177/0091270011407068

Damal K, Stoker E, Foley JF (2013) Optimizing therapeutics in the management of patients with multiple sclerosis: a review of drug efficacy, dosing, and mechanisms of action. Biologics 7:247–258. doi:10.2147/BTT.S53007

Toker A, Slaney CY, Backstrom BT, Harper JL (2011) Glatiramer acetate treatment directly targets CD11b+Ly6G− monocytes and enhances the suppression of autoreactive T cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Scand J Immunol 74:235–243. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.2011.02575.x

Linker RA, Lee DH, Ryan S, van Dam AM, Conrad R, Bista P et al (2011) Fumaric acid esters exert neuroprotective effects in neuroinflammation via activation of the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway. Brain 134:678–692. doi:10.1093/brain/awq386

Scannevin RH, Chollate S, Jung MY, Shackett M, Patel H, Bista P et al (2012) Fumarates promote cytoprotection of central nervous system cells against oxidative stress via the nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 341:274–284. doi:10.1124/jpet.111.190132

Bomprezzi R (2015) Dimethyl fumarate in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: an overview. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 8:20–30. doi:10.1177/1756285614564152

Fox RJ, Chan A, Gold R, Phillips JT, Selmaj K, Chang I et al (2016) Characterizing absolute lymphocyte count profiles in dimethyl fumarate-treated patients with MS: patient management considerations. Neurol Clin Pract 6:220–229. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000238

Buckle G, Bandari D, Greenstein J, Gudesblatt M, Khatri B, Kita M et al (2016) Effect of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate on lymphocyte subsets in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: a retrospective, multicentre, observational study (REALIZE). Mult Scler 22(3 suppl):EP1495

Spencer CM, Crabtree-Hartman EC, Lehmann-Horn K, Cree BA, Zamvil SS (2015) Reduction of CD8+ T lymphocytes in multiple sclerosis patients treated with dimethyl fumarate. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2:e76. doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000076

Longbrake EE, Naismith RT, Parks BJ, Wu GF, Cross AH (2015) Dimethyl fumarate-associated lymphopenia: risk factors and clinical significance [published online 31 July 2015]. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. doi:10.1177/2055217315596994

Biogen (2017) Tecfidera [prescribing information]. Biogen, Cambridge, MA, USA

Rosenkranz T, Novas M, Terborg C (2015) PML in a patient with lymphocytopenia treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med 372:1476–1478. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1415408

European Medicines Agency (2015) Updated recommendations to minimise the risk of the rare brain infection PML with Tecfidera. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Press_release/2015/10/WC500196017.pdf. Accessed 7 April 2016

Zeyda M, Poglitsch M, Geyeregger R, Smolen JS, Zlabinger GJ, Hörl WH et al (2005) Disruption of the interaction of T cells with antigen-presenting cells by the active leflunomide metabolite teriflunomide: involvement of impaired integrin activation and immunologic synapse formation. Arthritis Rheum 52:2730–2739. doi:10.1002/art.21255

Comi G, Freedman MS, Kappos L, Olsson TP, Miller AE, Wolinsky JS et al (2016) Pooled safety and tolerability data from four placebo-controlled teriflunomide studies and extensions. Mult Scler Relat Disord 5:97–104. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2015.11.006

Genzyme (2016) Aubagio [prescribing information]. Genzyme Corporation, Cambridge, MA, USA

European Medicines Agency (2013) Aubagio 14 mg film-coated tablets [summary of product characteristics]. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002514/WC500148682.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2016

FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (2016) Teriflunomide (Aubagio). Safety labelling changes. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20161023083238/http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm423101.htm. Accessed 22 Aug 2016

Gerschenfeld G, Servy A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, de Prost N, Cecchini J (2015) Fatal toxic epidermal necrolysis in a patient on teriflunomide treatment for relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 21:1476–1477. doi:10.1177/1352458515596601

Gajofatto A, Turatti M, Monaco S, Benedetti MD (2015) Clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability of fingolimod for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Drug Healthc Patient Saf 7:157–167. doi:10.2147/DHPS.S69640

Johnson TA, Evans BL, Durafourt BA, Blain M, Lapierre Y, Bar-Or A, Antel JP (2011) Reduction of the peripheral blood CD56bright NK lymphocyte subset in FTY720-treated multiple sclerosis patients. J Immunol 187:570–579. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1003823

Johnson TA, Shames I, Keezer M, Lapierre Y, Haegert DG, Bar-Or A, Antel J (2010) Reconstitution of circulating lymphocyte counts in FTY720-treated MS patients. Clin Immunol 137:15–20. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2010.06.005

Alroughani R, Almulla A, Lamdhade S, Thussu A (2014) Multiple sclerosis reactivation postfingolimod cessation: is it IRIS? BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-206314

FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (2016) Gilenya (fingolimod) capsules 0.5 mg. Safety labeling changes. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170112171747/http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm266123.htm. Accessed 20 April 2016

European Medicines Agency (2016) Zinbryta 150 mg solution for injection in pre-filled syringe, Zinbryta 150 mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen [summary of product characteristics]. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/003862/WC500210598.pdf. Accessed 20 July 2017

Biogen (2017) Zinbryta [prescribing information]. Biogen, Cambridge, MA, USA

Therapeutic Goods Administration (2017) Prescription medicines: registration of new chemical entities in Australia, 2016. https://www.tga.gov.au/prescription-medicines-registration-new-chemical-entities-australia-2016. Accessed 21 April 2017

Bielekova B (2013) Daclizumab therapy for multiple sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics 10:55–67. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0147-4

Malek TR (2008) The biology of interleukin-2. Annu Rev Immunol 26:453–479. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090357

Milo R (2014) The efficacy and safety of daclizumab and its potential role in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 7:7–21. doi:10.1177/1756285613504021

Wiendl H, Gross CC (2013) Modulation of IL-2Rα with daclizumab for treatment of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 9:394–404. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2013.95

Martin JF, Perry JS, Jakhete NR, Wang X, Bielekova B (2010) An IL-2 paradox: blocking CD25 on T cells induces IL-2–driven activation of CD56bright NK cells. J Immunol 185:1311–1320. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0902238

Perry JS, Han S, Xu Q, Herman ML, Kennedy LB, Csako G, Bielekova B (2012) Inhibition of LTi cell development by CD25 blockade is associated with decreased intrathecal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Sci Transl Med 4:145ra106. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004140

Bielekova B, Catalfamo M, Reichert-Scrivner S, Packer A, Cerna M, Waldmann TA et al (2006) Regulatory CD56bright natural killer cells mediate immunomodulatory effects of IL-2Rα-targeted therapy (daclizumab) in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:5941–5946. doi:10.1073/pnas.0601335103

Bielekova B, Howard T, Packer AN, Richert N, Blevins G, Ohayon J et al (2009) Effect of anti-CD25 antibody daclizumab in the inhibition of inflammation and stabilization of disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 66:483–489. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2009.50

Gold R, Giovannoni G, Selmaj K, Havrdova E, Montalban X, Radue EW, SELECT study Investigators et al (2013) Daclizumab high-yield process in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (SELECT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 381:2167–2175. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62190-4

Amaravadi L, Mokliatchouk O, Mehta D, Riester K, Sheridan J, Elkins J (2015) Early, sustained, and reversible pharmacodynamic effects of daclizumab HYP in MS support mechanism of action via modulation of the IL-2 pathway. Neurology 84(14 suppl):P1.149

Huss DJ, Mehta DS, Sharma A, You X, Riester KA, Sheridan JP et al (2015) In vivo maintenance of human regulatory T cells during CD25 blockade. J Immunol 194:84–92. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1402140

Fam S, Mokliatchouk O, Mehta D, Riester K, Sheridan S, McCroskery P, Elkins J (2016) Reversible effects of daclizumab HYP on lymphocyte counts in RRMS patients: data from the SELECT trilogy studies. Neurology 86(16 suppl):P5.281

Diao L, Hang Y, Othman AA, Nestorov I, Tran JQ (2016) Population pharmacokinetics of daclizumab high-yield process in healthy volunteers and subjects with multiple sclerosis: analysis of phase I-III clinical trials. Clin Pharmacokinet 55:943–955. doi:10.1007/s40262-016-0366-7

Kappos L, Cohan S, Arnold DL, Mokliatchouk O, Greenberg SJ, McCroskery P, Lima G (2016) Interim report on the safety and efficacy of long-term daclizumab HYP treatment for up to 5 years in EXTEND. Mult Scler 22(3 suppl):P653

Giovannoni G, Kappos L, Gold R, Khatri BO, Selmaj K, Umans K et al (2016) Safety and tolerability profile of daclizumab in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: an integrated analysis of clinical studies. Mult Scler Relat Disord 9:36–46. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2016.05.010

Babij R, Perumal JS (2015) Comparative efficacy of alemtuzumab and established treatment in the management of multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11:1221–1229. doi:10.2147/NDT.S60518

Genzyme (2016) Lemtrada [prescribing information]. Genzyme Corporation, Cambridge, MA, USA

Hill-Cawthorne GA, Button T, Tuohy O, Jones JL, May K, Somerfield J et al (2012) Long term lymphocyte reconstitution after alemtuzumab treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83:298–304. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2011-300826

Thompson SA, Jones JL, Cox AL, Compston DA, Coles AJ (2010) B-cell reconstitution and BAFF after alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Clin Immunol 30:99–105. doi:10.1007/s10875-009-9327-3

Durelli L, De Mercanti S, Rolla S, Cucci A, Bardina V, Cocco E et al (2016) Alemtuzumab long term immunological study: the immunosuppressive effect does not last more than 48 months. Neurology 86(S2):008

Cossburn MD, Harding K, Ingram G, El-Shanawany T, Heaps A, Pickersgill TP et al (2013) Clinical relevance of differential lymphocyte recovery after alemtuzumab therapy for multiple sclerosis. Neurology 80:55–61. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827b5927

Coles AJ, Twyman CL, Arnold DL, Cohen JA, Confavreux C, Fox EJ, CARE-MS II Investigators et al (2012) Alemtuzumab for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis after disease-modifying therapy: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 380:1829–1839. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61768-1

Khatri BO, Man S, Giovannoni G, Koo AP, Lee JC, Tucky B et al (2009) Effect of plasma exchange in accelerating natalizumab clearance and restoring leukocyte function. Neurology 72:402–409. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000341766.59028.9d

Plavina T, Muralidharan KK, Kuesters G, Mikol D, Evans K, Subramanyam M et al (2016) Natalizumab’s effects on peripheral immune cells in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are reversible by 16–20 weeks after treatment discontinuation. Neurology 86(16 suppl):P5.408

Bloomgren G, Richman S, Hotermans C, Subramanyam M, Goelz S, Natarajan A et al (2012) Risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med 366:1870–1880. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1107829

Koendgen H, Chang I, Sperling B, Bloomgren G, Richman S, Ho PR, Campbell N (2016) New algorithm to estimate risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in anti-JCV antibody positive patients: analyses of clinical trial data to provide further temporal precision and inform clinical practice. Mult Scler 22(3 suppl):P1249

Plavina T, Subramanyam M, Bloomgren G, Richman S, Pace A, Lee S et al (2014) Anti-JC virus antibody levels in serum or plasma further define risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol 76:802–812. doi:10.1002/ana.24286

Kuesters G, Plavina T, Lee S, Campagnolo D, Richman S, Belachew S, Subramanyam M (2015) Anti-JC virus (JCV) antibody index differentiates risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in natalizumab-treated multiple sclerosis (MS) patients with no prior immunosuppressant (IS) use: an updated analysis. Neurology 84(14 suppl):P4.031

Gobbi C, Meier DS, Cotton F, Sintzel M, Leppert D, Guttmann CR, Zecca C (2013) Interferon beta 1b following natalizumab discontinuation: one year, randomized, prospective, pilot trial. BMC Neurol 13:101. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-13-101

Cohen M, Maillart E, Tourbah A, De Seze J, Vukusic S, Brassat D, Club Francophone de la Sclerose en Plaques Investigators et al (2014) Switching from natalizumab to fingolimod in multiple sclerosis: a French prospective study. JAMA Neurol 71:436–441. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.6240

Malucchi S, Capobianco M, Lo Re M, Malentacchi M, di Sapio A, Matta M et al (2016) High-risk PML patients switching from natalizumab to alemtuzumab: an observational study [published online 3 December 2016]. Neurol Ther. doi:10.1007/s40120-016-0058-0

Alping P, Frisell T, Novakova L, Islam-Jakobsson P, Salzer J, Bjorck A et al (2016) Rituximab versus fingolimod after natalizumab in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol 79:950–958. doi:10.1002/ana.24651

Alvarez E, Vollmer B, Jace B, Corboy J, Vollmer T, Sillou SH et al (2015) Effectiveness of switching to rituximab over fingolimod or dimethyl fumarate after natalizumab in preventing disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 84(14 suppl):P3.288

Maillart E, Vidal JS, Brassat D, Stankoff B, Fromont A, de Seze J et al (2017) Natalizumab-PML survivors with subsequent MS treatment: clinico-radiologic outcome. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 4:e346. doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000346

Genentech (2017) Ocrevus [prescribing information]. Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA

Sorensen PS, Blinkenberg M (2016) The potential role for ocrelizumab in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: current evidence and future prospects. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 9:44–52. doi:10.1177/1756285615601933

Hauser SL, Bar-Or A, Comi G, Giovannoni G, Hartung HP, Hemmer B, OPERA I and OPERA II Clinical Investigators et al (2017) Ocrelizumab versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 376:221–234. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1601277

National Multiple Sclerosis Society (2017) Vaccinations. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/Living-Well-With-MS/Health-Wellness/Vaccinations. Accessed 22 April 2017

Cunningham AL, Lal H, Kovac M, Chlibek R, Hwang SJ, Diez-Domingo J et al (2016) Efficacy of the herpes zoster subunit vaccine in adults 70 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 375:1019–1032. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1603800

Gruver AL, Hudson LL, Sempowski GD (2007) Immunosenescence of ageing. J Pathol 211:144–156. doi:10.1002/path.2104

Axtell RC, de Jong BA, Boniface K, van der Voort LF, Bhat R, De Sarno P et al (2010) T helper type 1 and 17 cells determine efficacy of interferon-ß in multiple sclerosis and experimental encephalomyelitis. Nat Med 16:406–412. doi:10.1038/nm.2110

Grossman I, Avidan N, Singer C, Goldstaub D, Hayardeny L, Eyal E et al (2007) Pharmacogenetics of glatiramer acetate therapy for multiple sclerosis reveals drug–response markers. Pharmacogenet Genomics 17:657–666. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e3281299169

Steinberg SC, Faris RJ, Chang CF, Chan A, Tankersley MA (2010) Impact of adherence to interferons in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a non-experimental, retrospective, cohort study. Clin Drug Investig 30:89–100. doi:10.2165/11533330-000000000-00000