Abstract

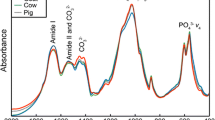

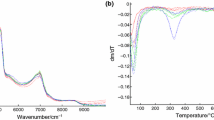

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy is a fast and accessible, minimally or non-destructive technique which provides information on physiochemical characteristics of analyzed materials. In forensic and archaeological sciences, it is commonly used for answering numerous questions, including the archaeological or forensic context of the human skeletal remains. In this research, the accuracy of ATR-FTIR-obtained spectra for separation between forensic, WWII, and archaeological human skeletal remains was investigated. Building from the previously proposed methodological procedures, various ratio-based and whole spectra separation procedures were applied, carefully analyzed, and evaluated. Results showed that employing whole spectral domains works best for the separation of archaeological, WWII, and forensic samples, even with samples of highly variable origin. Principal component analysis (PCA) further highlighted the necessity of acknowledging all the major components in the remains: amides, phosphates, and carbonates for the separation. Most influential proved to be amide I, namely its secondary structure, which presented well-preserved and organized collagen structure in forensic and WWII samples, while highly degraded in archaeological samples. Using the whole spectral domain for separation between samples from different contexts proved to be fast and simple, with no manipulation beyond baseline correction and normalization of spectra necessary. However, a dataset with samples of known origin is required for the learning model and predictions. A less accurate alternative is separation based on combining ratios of peaks correlating to organics and minerals in the bone, which eliminated overlapping and managed to classify the majority of the samples correctly as archaeological, WWII, or forensic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In Slovenia, the victims from the WWII mass graves are under the jurisdiction of The Commission on Concealed Mass Graves and are processed by either National Forensic Institute or Institute of Forensic Medicine.

For a review on the peak assignment see for example Figueiredo et al. 2010 and Lopes et al. 2018.

References

Figueiredo MM, Gamelas JAF, Martins AG (2012) Characterization of bone and bone-based graft materials using FTIR spectroscopy. In: Theophile T (ed) Infrared spectroscopy - life and biomedical sciences. InTech, Rijeka, pp 315–338

Lopes C de CA, Limirio PHJO, Novais VR, Dechichi P (2018) Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) application chemical characterization of enamel, dentin and bone. Appl Spectrosc Rev 53:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/05704928.2018.1431923

Weiner S, Bar-Yosef O (1990) States of preservation of bones from prehistoric sites in the Near East: a survey. J Archaeol Sci 17:187–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-4403(90)90058-D

Garvie-Lok SJ, Varney TL, Katzenberg MA (2004) Preparation of bone carbonate for stable isotope analysis: the effects of treatment time and acid concentration. J Archaeol Sci 31:763–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2003.10.014

Thompson TJ (2005) Heat-induced dimensional changes in bone and their consequences for forensic anthropology. J Forensic Sci 50:1008–1015

Chadefaux C, Le Hô A-S, Bellot-Gurlet L, Reiche I (2009) Curve-fitting micro-ATR-FTIR studies of the amide I and II bands of type I collagen in archaeological bone materials. e-Preserv Sci 6:129–137

Lebon M, Reiche I, Bahain JJ, Chadefaux C, Moigne AM, Fröhlich F, Sémah F, Schwarcz HP, Falguères C (2010) New parameters for the characterization of diagenetic alterations and heat-induced changes of fossil bone mineral using Fourier transform infrared spectrometry. J Archaeol Sci 37:2265–2276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2010.03.024

Gonçalves D, Thompson TJU, Cunha E (2011) Implications of heat-induced changes in bone on the interpretation of funerary behaviour and practice. J Archaeol Sci 38:1308–1313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2011.01.006

Lebon M, Zazzo A, Reiche I (2014) Screening in situ bone and teeth preservation by ATR-FTIR mapping. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 416:110–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.08.001

Snoeck C, Schulting RJ, Lee-Thorp JA, Lebon M, Zazzo A (2016) Impact of heating conditions on the carbon and oxygen isotope composition of calcined bone. J Archaeol Sci 65:32–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2015.10.013

Patonai Z, Maasz G, Avar P, Schmidt J, Lorand T, Bajnoczky I, Mark L (2013) Novel dating method to distinguish between forensic and archeological human skeletal remains by bone mineralization indexes. Int J Legal Med 127:529–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-012-0785-4

Woess C, Unterberger SH, Roider C, Ritsch-Marte M, Pemberger N, Cemper-Kiesslich J, Hatzer-Grubwieser P, Parson W, Pallua JD (2017) Assessing various infrared (IR) microscopic imaging techniques for post-mortem interval evaluation of human skeletal remains. PLoS One 12:e0174552

Amadasi A, Cappella A, Cattaneo C, Cofrancesco P, Cucca L, Merli D, Milanese C, Pinto A, Profumo A, Scarpulla V, Sguazza E (2017) Determination of the post mortem interval in skeletal remains by the comparative use of different physico-chemical methods: are they reliable as an alternative to14C? HOMO- J Comp Hum Biol 68:213–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchb.2017.03.006

Longato S, Wöss C, Hatzer-Grubwieser P, Bauer C, Parson W, Unterberger SH, Kuhn V, Pemberger N, Pallua AK, Recheis W, Lackner R, Stalder R, Pallua JD (2015) Post-mortem interval estimation of human skeletal remains by micro-computed tomography, mid-infrared microscopic imaging and energy dispersive X-ray mapping. Anal Methods 7:2917–2927. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4AY02943G

Howes JM, Stuart BH, Thomas PS, Raja S, O’Brien C (2012) An investigation of model forensic bone in soil environments studied using infrared spectroscopy. J Forensic Sci 57:1161–1167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2012.02236.x

Tătar A, Ponta O, Kelemen B (2014) Bone diagenesis and ftir indices: a correlation Stud Univ BABEŞ-BOLYAI Biol LIX, pp 101–113

Ou-Yang H, Paschalis EP, Mayo WE, Boskey AL, Mendelsohn R (2001) Infrared microscopic imaging of bone: spatial distribution of CO3(2−). J Bone Miner Res 16:893–900. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.5.893

Márquez-Grant N, Webster H, Truesdell J, Fibiger L (2016) Physical anthropology and osteoarchaeology in Europe: history, current trends and challenges. Int J Osteoarchaeol 26:1078–1088. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.2520

Ferenc M (2008) Topografija evidentiranih grobišč (Topography of documented mass graves). In: Dežman J (ed) Poročilo Komisije Vlade Republike Slovenije za reševanje vprašanj prikritih grobišč 2005–2008. Družina, Ljubljana, pp 7–27

Zupanic Pajnic I, Gornjak Pogorelc B, Balazic J (2010) Molecular genetic identification of skeletal remains from the Second World War Konfin I mass grave in Slovenia. Int J Legal Med 124:307–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-010-0431-y

Pilli E, Boccone S, Agostino A, Virgili A, D’Errico G, Lari M, Rapone C, Barni F, Moggi Cecchi J, Berti A, Caramelli D (2018) From unknown to known: identification of the remains at the mausoleum of fosse Ardeatine. Sci Justice 58:469–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scijus.2018.05.007

Ríos L, García-Rubio A, Martínez B, Alonso A, Puente J (2012) Identification process in mass graves from the Spanish Civil War II. Forensic Sci Int 219:e4–e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.11.021

Baeta M, Núñez C, Cardoso S, Palencia-Madrid L, Herrasti L, Etxeberria F, de Pancorbo MM (2015) Digging up the recent Spanish memory: genetic identification of human remains from mass graves of the Spanish Civil War and posterior dictatorship. Forensic Sci Int Genet 19:272–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2015.09.001

Zupanič Pajnič I (2008) Molecular genetic identification of the Slovene home guard victims. Slov Med J 77

Zupanič Pajnič I, Petaros A, Balažic J, Geršak K (2016) Searching for the mother missed since the Second World War. J Forensic Legal Med 44:138–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2016.10.015

Chaitanya L, Pajnič IZ, Walsh S, Balažic J, Zupanc T, Kayser M (2017) Bringing colour back after 70 years: predicting eye and hair colour from skeletal remains of World War II victims using the HIrisPlex system. Forensic Sci Int Genet 26:48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2016.10.004

Marjanović D, Durmić-Pasić A, Bakal N, Haverić S, Kalamujić B, Kovacević L, Ramić J, Pojskić N, Skaro V, Projić P, Bajrović K, Hadziselimović R, Drobnic K, Huffine E, Davoren J, Primorac D (2007) DNA identification of skeletal remains from the World War II mass graves uncovered in Slovenia. Croat Med J 48:513–519

Marjanović D, Durmić-Pasić A, Kovacević L, Avdić J, Dzehverović M, Haverić S, Ramić J, Kalamujić B, Lukić Bilela L, Skaro V, Projić P, Bajrović K, Drobnic K, Davoren J, Primorac D (2009) Identification of skeletal remains of Communist Armed Forces victims during and after World War II: combined Y-chromosome (STR) and MiniSTR approach. Croat Med J 50:296–304. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2009.50.296

Ossowski A, Diepenbroek M, Kupiec T, Bykowska-Witowska M, Zielińska G, Dembińska T, Ciechanowicz A (2016) Genetic identification of communist crimes’ victims (1944–1956) based on the analysis of one of many mass graves discovered on the Powazki Military Cemetery in Warsaw, Poland. J Forensic Sci 61:1450–1455. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13205

Ossowski A, Diepenbroek M, Zwolski M, Falis A, Wróbel M, Bykowska-Witowska M, Zielińska G, Szargut M, Kupiec T (2017) A case study of an unknown mass grave — hostages killed 70 years ago by a Nazi firing squad identified thanks to genetics. Forensic Sci Int 278:173–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2017.06.038

Morild I, Hamre SS, Huel R, Parsons TJ (2015) Identification of missing Norwegian World War II soldiers, in Karelia Russia. J Forensic Sci 60:1104–1110. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12767

Lazar E (2014) Zaščitne arheološke raziskave na območju dominikanskega samostana na Ptuju. ČZN 85:41–54

Murko M (2014) Poročilo o arheoloških izkopavanjih v Minoritski cerkvi v Mariboru 2013/2014. Slovenska Bistrica

Leskovar T, Novšak M, Verbič T (2012) Poročilo o opravljenih arheoloških raziskavah na lokaciji Ponikva. Arhej d.o.o., Ljubljana

Leben-Seljak P (1996) Antropoloska analiza poznoantičnih in srednjeveških grobišč Bleda in okolice: doktorska disertacija = anthropological analysis of late antiquity and medieval necropolises at Bled and surroundings : disertation thesis. University of Ljubljana

Knific T (1977) Arheolosko raziskovanje grobisca bled-pristava. RSS

Mikl Curk I (1990) Prostorska ureditev grobišč rimskega ptuja. Arheol vestink 41:557–576

Wilson MR, DiZinno JA, Polanskey D, Replogle J, Budowle B (1995) Validation of mitochondrial DNA sequencing for forensic casework analysis. Int J Legal Med 108:68–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01369907

Amory S, Huel R, Bilić A, Loreille O, Parsons TJ (2012) Automatable full demineralization DNA extraction procedure from degraded skeletal remains. Forensic Sci Int Genet 6:398–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2011.08.004

Carracedo A, Bär W, Lincoln P, Mayr W, Morling N, Olaisen B, Schneider P, Budowle B, Brinkmann B, Gill P, Holland M, Tully G, Wilson M (2000) DNA Commission of the International Society for Forensic Genetics: guidelines for mitochondrial DNA typing. Forensic Sci Int 110:79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0379-0738(00)00161-4

Pääbo S, Poinar H, Serre D, Jaenicke-Després V, Hebler J, Rohland N, Kuch M, Krause J, Vigilant L, Hofreiter M (2004) Genetic analyses from ancient DNA. Annu Rev Genet 38:645–679. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143214

Caputo M, Irisarri M, Alechine E, Corach D (2013) A DNA extraction method of small quantities of bone for high-quality genotyping. Forensic Sci Int Genet 7:488–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2013.05.002

Rohland N, Hofreiter M (2007) Ancient DNA extraction from bones and teeth. Nat Protoc 2:1756–1762

Buijs HL, Rochette L, Chateauneuf F (2004) Evolution of FTIR technology as applied to chemical detection and quantification. In: Chemical and Biological Point Sensors for Homeland Defense International Society for Optics and Photonics, pp 132–143

Surovell TA, Stiner MC (2001) Standardizing infra-red measures of bone mineral crystallinity: an experimental approach. J Archaeol Sci 28:633–642. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2000.0633

Wright LE, Schwarcz HP (1996) Infrared and isotopic evidence for diagenesis of bone apatite at Dos Pilas, Guatemala: palaeodietary implications. J Archaeol Sci 23:933–944. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1996.0087

Olsen J, Heinemeier J, Bennike P, Krause C, Margrethe Hornstrup K, Thrane H (2008) Characterisation and blind testing of radiocarbon dating of cremated bone. J Archaeol Sci 35:791–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2007.06.011

Thompson TJU, Gauthier M, Islam M (2009) The application of a new method of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to the analysis of burned bone. J Archaeol Sci 36:910–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2008.11.013

Trueman CNG, Behrensmeyer AK, Tuross N, Weiner S (2004) Mineralogical and compositional changes in bones exposed on soil surfaces in Amboseli National Park, Kenya: diagenetic mechanisms and the role of sediment pore fluids. J Archaeol Sci 31:721–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2003.11.003

Lebon M, Reiche I, Gallet X, Bellot-Gurlet L, Zazzo A (2016) Rapid quantification of bone collagen content by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. Radiocarbon 58:131–145

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A (2007) G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39:175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Kadam P, Bhalerao S (2010) Sample size calculation. Int J Ayurveda Res 1:55–57. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7788.59946

Das S, Mitra K, Mandal M (2016) Sample size calculation: basic principles. Indian J Anaesth 60:652–656. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5049.190621

Demšar J, Curk T, Erjavec A, Gorup Č, Hočevar T, Milutinovič M, Možina M, Polajnar M, Toplak M, Starič A (2013) Orange: data mining toolbox in Python. J Mach Learn Res 14:2349–2353

Sheela KG, Deepa SN (2013) Review on methods to fix number of hidden neurons in neural networks. Math Probl Eng 2013:1–11

Child AM (1995) Microbial taphonomy of archaeological bone. Stud Conserv 40:19–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/1506608

Bell LS, Skinner MF, Jones SJ (1996) The speed of post mortem change to the human skeleton and its taphonomic significance. Forensic Sci Int 82:129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/0379-0738(96)01984-6

Marcella HS, Hagalund WD (2001) Advancing forensic taphonomy: purpose, theory, and practice. In: Haglund WD, Sorg MH (eds) Advances in forensic taphonomy. CRC Press, pp 3–30

Denys C (2002) Taphonomy and experimentation. Archaeometry 44:469–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4754.00079

Creagh D, Cameron A (2017) Estimating the post-mortem interval of skeletonized remains: the use of infrared spectroscopy and Raman spectro-microscopy. Radiat Phys Chem 137:225–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2016.03.007

Fernández-Jalvo Y, Andrews P, Pesquero D, Smith C, Marín-Monfort D, Sánchez B, Geigl EM, Alonso A (2010) Early bone diagenesis in temperate environments: part I: surface features and histology. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 288:62–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.12.016

López-Costas O, Lantes-Suárez Ó, Martínez Cortizas A (2016) Chemical compositional changes in archaeological human bones due to diagenesis: type of bone vs soil environment. J Archaeol Sci 67:43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.02.001

Collins MJ, Nielsen-Marsh CM, Hiller J, Smith CI, Roberts JP, Prigodich RV, Wess TJ, Csapo J, Millard AR, Turner-Walker G (2002) The survival of organic matter in bone: a review. Archaeometry 44:383–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4754.t01-1-00071

Hedges REM, Millard AR, Pike AWG (1995) Measurements and relationships of diagenetic alteration of bone from three archaeological sites. J Archaeol Sci 22:201–209. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1995.0022

Nielsen-Marsh CM, Hedges REM (2000) Patterns of diagenesis in bone I: the effects of site environments. J Archaeol Sci 27:1139–1150. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1999.0537

Habermehl J, Skopinska J, Boccafoschi F, Sionkowska A, Kaczmarek H, Laroche G, Mantovani D (2005) Preparation of ready-to-use, stockable and reconstituted collagen. Macromol Biosci 5:821–828. https://doi.org/10.1002/mabi.200500102

Payne KJ, Veis A (1988) Fourier transform ir spectroscopy of collagen and gelatin solutions: deconvolution of the amide I band for conformational studies. Biopolymers 27:1749–1760. https://doi.org/10.1002/bip.360271105

Chang MC, Tanaka J (2002) FT-IR study for hydroxyapatite/collagen nanocomposite cross-linked by glutaraldehyde. Biomaterials 23:4811–4818. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-9612(02)00232-6

Hassan AA, Termine JD, Haynes CV (1977) Mineralogical studies on bone apatite and their implications for radiocarbon dating. Radiocarbon 19:364–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033822200003684

Sponheimer M, Lee-Thorp JA (2001) The oxygen isotope composition of mammalian enamel carbonate from Morea Estate, South Africa. Oecologia 126:153–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420000498

Lebon M, Reiche I, Fröhlich F, Bahain JJ, Falguères C (2008) Characterization of archaeological burnt bones: contribution of a new analytical protocol based on derivative FTIR spectroscopy and curve fitting of the ν 1 ν 3 PO4 domain. Anal Bioanal Chem 392:1479–1488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-008-2469-y

Snoeck C, Lee-Thorp JA, Schulting RJ (2014) From bone to ash: compositional and structural changes in burned modern and archaeological bone. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 416:55–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.08.002

Tu JV (1996) Advantages and disadvantages of using artificial neural networks versus logistic regression for predicting medical outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 49:1225–1231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00002-9

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jože Grdadolnik from the National Institute of Chemistry for making the use Bruker Vertex 80 spectrometer possible, and to the Governmental Commission on Concealed Mass Graves of the Republic of Slovenia for their support in excavations of Second World War victims. Furthermore, we would like to thank the head of the Centre for Preventive Archaeology of the Institute for the protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia (IPCHS CPA) Barbara Nadbath for recognizing this research as important for the development of operational procedures in the heritage protection field. Our thanks also goes to Dr. Maja Janežič, Monika Arh, Marija Lubšina Tušek, Miha Murko, Evgen Lazar (all IPCHS CPA), and Matjaž Novšak (Arhej d. o. o.) for all the information about the archaeological remains form the archives, as well as Dr. Timotej Knific (National Museum of Slovenia) and Vesna Koprivnik (Regional Museum of Maribor) for including the archaeological human remains from their museums into our study.

Funding

This study was partially financially supported by the Slovenian Research Agency (project “Determination of the most appropriate skeletal elements for molecular genetic identification of aged human remains” (J3-8214)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

The research project was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Republic of Slovenia (0120-350/2018/6).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 734 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leskovar, T., Zupanič Pajnič, I., Jerman, I. et al. Separating forensic, WWII, and archaeological human skeletal remains using ATR-FTIR spectra. Int J Legal Med 134, 811–821 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-019-02079-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-019-02079-0