Abstract

Cognitive impairment is one of the core symptoms of schizophrenia. Quite a number of systematic reviews were published related to cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia (PWS). This umbrella review, therefore, aimed at reviewing and synthesizing the findings of systematic reviews related to domains of cognition impaired and associated factors in PWS. We searched four electronic databases. Data related to domains, occurrence, and associated factors of cognitive impairment in PWS were extracted. The quality of all eligible systematic reviews was assessed using A MeaSurement Tool to Assess methodological quality of systematic Review (AMSTAR) tool. Results are summarized and presented in a narrative form. We identified 63 systematic reviews fulfilling the eligibility criteria. The included reviews showed that PWS had lower cognitive functioning compared to both healthy controls and people with affective disorders. Similar findings were reported among psychotropic free cases and people with first episode psychosis. Greater impairment of cognition was reported in processing speed, verbal memory, and working memory domains. Greater cognitive impairment was reported to be associated with worse functionality and poor insight. Cognitive impairment was also reported to be associated with childhood trauma and aggressive behaviour. According to our quality assessment, the majority of the reviews had moderate quality. We were able to find a good number of systematic reviews on cognitive impairment in PWS. The reviews showed that PWS had higher impairment in different cognitive domains compared to healthy controls and people with affective disorders. Impairment in domains of memory and processing speed were reported frequently.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cognitive function is a mental process which involves several intellectual abilities such as perception, reasoning, and remembering, while cognitive impairment is the malfunction of cognition or intellectual abilities [1]. Cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia (PWS) can be considered as part of core symptoms of the disorder because: (1) almost all (98%) PWS showed cognitive decrement compared to their premorbid state [2], (2) PWS showed a broader domains of cognitive impairment with varying severity per domain [3], and (3) cognitive impairment is seen in PWS who are not taking anti-psychotic drugs [4].

Cognitive impairment in PWS was recognized from as early as the time of Emil Kraepelin, where Kraepelin named the disorder as dementia praecox to mean early-onset dementia (although due attention has not been given to it) [5]. However, different groups are now working to improve cognitive impairment in PWS as part of the intervention for the problem [6, 7]. One of these groups is the Measurement And Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) initiative [6]. The MATRICS initiative, through review of factor analytical studies and consensus, identified seven domains of cognition which are more affected in PWS [8]. Brief description of each of these domains is given below (Table 1).

A large number of articles are published on cognitive impairment in PWS. A simple hit of “Cognition AND Schizophrenia” in PubMed yields around 30,000 articles. Consequently, quite a number of systematic reviews have been published on the subject. Although there are numerous systematic reviews on the magnitude of cognitive domains impaired and associated factors in PWS, we found only one published umbrella review on the subject [9]. However, this umbrella review has not addressed factors associated with cognitive impairment; and it only focused on the difference in the magnitude of cognitive impairment between PWS and people with bipolar disorder.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders (DSM) [5] and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) [10] have not, to date, considered cognitive impairment in their diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia. Whereas, cognitive impairment seems to be one of the core symptoms of this illness. In this umbrella review, we aimed to explore the evidence that cognitive impairment maybe a common problem in PWS by examining findings from systematic reviews and meta-analysis related to magnitude of cognitive domains impaired and associated factors in PWS. This umbrella review might help clinicians and experts in the area to have a comprehensive understanding of domains of cognition affected, and related factors in PWS. Additionally, this review would inform future researchers regarding which factors need to be considered while planning studies involving cognitive impairment in PWS. This umbrella review, therefore, aimed at synthesizing the evidence on magnitude of cognitive domains impaired and associated factors in PWS from systematic review studies.

Methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline to identify, search, extract articles, and report this umbrella review [11].

Databases searched

We searched major databases, including PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and Global Index Medicus from the date of inception of each database until July 05, 2018. An update search from the same databases was conducted on 13th August 2020. Google Scholar was used for forward and backward searching.

Search strategy

We used the following three key words: schizophrenia, Cognition, and Magnitude/Associated factors. Free terms and controlled vocabulary terms were used for those three big terms. We combined those three big terms with the Boolean term “AND”. The term systematic review was not included in the initial search to allow collection of systematic reviews that did not mention systematic review in their title or abstract, however, we later filtered each databases for review or systematic review or meta-analysis or other related terms according to the filter method of the database. For the complete search strategy, see online resource 1. To increase our chance of capturing all systematic reviews about the magnitude and associated factors of cognitive impairment in PWS, we conducted a forward and backward search.

Eligibility criteria

This umbrella review considered reviews that aimed at assessing domains of cognitive impairment and associated factors among adult PWS aged 18 years and older. Diagnoses needed to have been confirmed using either DSM [5], ICD [10], or other recognized diagnostic criteria. For studies with mixed populations at least 50% of the participants should be PWS.

We included any systematic reviews or meta-analysis which addressed concepts related to magnitude and/or associated factors of at least one full domain of cognition in PWS. If the review was about sub-domains of a single domain then that review was excluded.

We only included systematic review studies. In this review, systematic review was operationalized as any review which had a search term, searched at least one database, had eligibility criteria to include studies, and reported the findings systematically [12]. We employed such a stringent definition of systematic review, because there were numerous unstructured reviews, expert comments, editorials, overviews, guidelines, and other non-systematic reviews on the subject.

No restriction was employed in terms of settings of the systematic reviews. However, systematic reviews published only in English were included into this umbrella review.

Full-text identification process

We merged the articles we found from the databases and removed duplicates. The first author (YG) screened each article for eligibility using their title and abstract, followed by full-text screening. While, another author (AM) screened 10% of the articles and we found good agreement. Same procedure was employed in screening articles obtained through forward and backward search.

Data extraction

The first author (YG) extracted data from the included articles using a data extraction tool developed a priori. Another author (AM) checked a randomly selected articles for correct extraction using the same extraction tool. The extraction tool was developed referring to previous published systematic reviews, and the requirements for quality assessment in consultation with the other co-authors. This was followed by piloting it on two articles (the data extraction template is in online resource 2). The core components of the data extraction tool include authors’ detail, databases searched, number of included studies, total number of participants included, cognitive domains addressed, and findings about cognitive impairment and associated factors.

Risk of bias/quality assessment

The first author (YG) and another author (AM) assessed the quality of each review using a critical appraisal form designed for evaluating the methodological quality of systematic reviews: a measurement tool to assess methodological quality of systematic Review (AMSTAR) [13]. AMSTAR has eleven items each to be scored as one for “yes” and zero for “no”. The eleven items focused on the presence of a prior registration of the protocol, study identification process, quality assessment section, and other steps of conducting a review. A score of 8 or more is considered as a good-quality review, a score of 4 to 7 a moderate quality, and a score below 4 a poor-quality review.

Data synthesis

We used a narrative synthesis to report the findings in this review. A narrative synthesis approach was selected as this approach is more appropriate to summarize studies with heterogeneous outcomes. For each systematic review included, we have reported the databases searched, number of included studies, total number of participants in each group (if more than one group was involved), specific cognitive domains evaluated, and findings related to magnitude and associated factors of cognitive impairment. We have also reported methodological qualities of each review included. We have presented the findings considering the methodological quality of the reviews included.

Results

Study characteristics

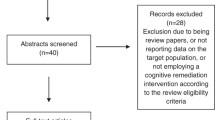

The search yielded a total of 7734 articles (i.e., 6607 articles in the initial search and 1127 on the updated search). Title and abstract screening yielded 87 articles, while full-text screening, and forward and backward searching gave us 63 systematic reviews (Fig. 1). A list of excluded articles after full-text screening with the reason for their exclusion is provided in online resource 3.

All the included systematic reviews evaluated cognitive impairment and associated factors in PWS with no geographical restriction, except one review from China. A diverse group of mental disorders were included in each review. In all the reviews, PWS were either compared within schizophrenia group or with other population groups, such as people with affective disorder or healthy controls. The majority of the reviews searched both PubMed and PsycINFO databases (n = 39). The quality of most of the included reviews was moderate (n = 38). We identified the following four themes from analysis of the data extracted from the included reviews.

-

1.

Domains of cognition impaired in PWS from specific single cognitive domain reviews (n = 15/63)

-

2.

Comparison of cognitive impairment in PWS with different groups from reviews with multiple domains (n = 17/63)

-

3.

Course/progress of cognitive impairment in PWS over time (n = 6/63)

-

4.

Cognitive impairment in PWS and associated factors (n = 25/63)

Domains of cognition impaired in PWS from specific single cognitive domain reviews

We identified a total of 15 systematic reviews which assessed the magnitude of cognitive impairment in PWS in a specific single cognitive domain. Five assessed memory, four executive function, two processing speed, two verbal fluency, and two social cognition. These reviews were published between 1999 and 2019. The majority of the reviews (n = 9/15) searched both PubMed and PsycINFO, and they included from 10 to 124 independent studies (1 review did not report the number of studies included). Ten of the 15 systematic reviews had moderate quality, while the remaining five studies had poor quality. Detailed description of the reviews included are given in (Table 2).

The most frequently studied domain of cognition is memory; 5 of the 15 systematic reviews [14,15,16,17,18] included were about different kinds of memory impairment in PWS. In all types of memory examined (spatial working memory, short-term and long-term memory, working memory, episodic memory, and semantic memory), PWS were found to have more impairment compared to healthy controls. The second most commonly studied domain was executive function. Four systematic reviews [19,20,21,22] included were about the level of impairment in executive function in PWS. All the four reviews reported that PWS had greater impairment in executive function compared to healthy controls. Two reviews [23, 24] were on processing speed. These reviews found that PWS had greater impairment in processing speed compared to controls. The level of impairment of verbal fluency was examined in two systematic reviews [25, 26], which found that PWS were more impaired in verbal fluency compared to healthy controls. Semantic fluency was reported to be more impaired in PWS compared to letter/phonetic fluency. Finally, other two systematic reviews [27, 28] included under this sub-section examined social cognition. Both reviews disclosed that in all domains of social cognition PWS performed worse compared to controls (Fig. 2).

Comparison of cognitive impairment in PWS with different groups from reviews with multiple domains

A total of 17 systematic reviews compared the magnitude of cognitive impairment in PWS with different groups in multiple domains of cognition. Of these, five reviews compared cognitive impairment in PWS and people with bipolar disorder/affective disorders and healthy controls; four compared cognitive impairment in PWS with healthy controls only. Five systematic reviews compared cognitive impairment in first episode/drug-free PWS with healthy controls. One review compared cognitive impairment in first episode schizophrenia patients with first episode bipolar patients and healthy controls. Two reviews compared cognitive domains to one another. Except for one which was rated as a good review, all the other reviews were of moderate quality (n = 12/17) or poor quality (n = 4/17) (Table 3).

From the reviews that compared cognitive impairment in PWS and people with bipolar disorder or other affective disorders, we found that PWS had significantly higher cognitive impairment compared to both people with bipolar disorder, or other affective disorders, and healthy controls, whereas people with bipolar disorder had intermediate cognitive impairment compared with PWS and healthy controls [29,30,31,32,33]. Regarding impairment in specific domains, one review [31], reported that greater impairment was observed in verbal fluency, whereas no difference was reported in the domains of delayed verbal memory, and fine motor skill between PWS and people with bipolar disorder. Similarly, another review [30] found that there was no significant group difference in the domains of verbal memory, attention (digit span), and spatial working memory between PWS and people with bipolar disorder.

Compared to healthy controls, PWS scored significantly lower across all cognitive domains [3, 34,35,36]. Looking at specific domains, greater impairment was found in the domains of processing speed and memory, whereas lower impairment was reported in domains of language and Intelligence Quotient (IQ) [34, 36].

We found that people with first episode schizophrenia were more impaired compared to healthy controls in multiple domains [37,38,39,40]. In the domain of verbal memory, greater impairment was reported in two reviews [37, 40]. Compared to people with first episode bipolar disorder cases and healthy controls, people with first episode schizophrenia were found to have worse performance while, people with bipolar disorder were reported to have cognitive impairment worse than healthy controls [41]. Similarly, in one systematic review of studies on cognitive impairment among treatment naive PWS [4], it was reported that PWS performed worse compared to healthy controls in all the domains considered, the three domains with greater impairment were verbal memory, processing speed, and working memory. These systematic reviews confirmed that cognitive impairment in PWS occurred in the absence of medication (i.e., antipsychotics).

Finally, two reviews focused on the relationship among the different cognitive domains. One of the two reviews [42] examined the relationship between theory of mind and neurocognitive domains. This review reported moderate association between theory of mind and each neurocognitive domain (Zrs 0.27–0.43), with no significant difference among domains in the neurocognitive domain. In the same review, stronger association was reported between theory of mind and executive function and abstraction domains. While the second review [43] that compared theory of mind impairment with executive function impairment reported that PWS had greater impairment in both domains and theory of mind continued to predict schizophrenia (rather than being a control participant) once executive function was controlled for. This review supported the hypothesis that theory of mind and executive function impairments in PWS are independent of one another.

Course/ progress of cognitive impairment in PWS over time

Six of the systematic reviews we identified were about the course of cognitive impairment in PWS [44,45,46,47,48,49]. Methodologically, two reviews were rated as poor and the other four were rated as moderate quality (Table 4).

Only one review [44] reported cognitive function decline over time. Even this review reported mixed results with slightly more studies pointing towards decline with a 1 to 1.2 ratio of no decline vs decline. This review was rated as poor quality with our criteria. To the contrary, two moderate-quality reviews [45, 46] reported no decline in cognitive function of PWS from follow-up studies. Most of the included studies in this review showed no difference between those treated with typical and atypical antipsychotics; among various atypical antipsychotics, and between medicated and un-medicated participants in terms of cognitive impairment [46]. One systematic review [47], which is a poor-quality review, reported improvement in cognitive function over time.

Two reviews [48, 49] examined the course of IQ in PWS, and both reviews found that PWS had lower performance in IQ test compared to controls. In both reviews, mixed results (i.e., both decline over time and no decline) were reported, where no decline over time was reported in better quality studies.

Cognitive impairment in PWS and associated factors

Twenty-five reviews focused on cognitive impairment in PWS and associated factors such as functionality, symptom dimensions, substance use, age of patients, insight into their problem, childhood trauma, duration of untreated psychosis, treatment, and aggressive behaviour. Seven of the 25 reviews examined the relationship between cognitive impairment and functionality, while four of them evaluated the relationship between cognitive impairment and substance use. Other four reviews examined the relationship between cognitive impairment and insight and two others each examined the relationship between cognitive impairment and symptom dimensions, duration of untreated psychosis, treatment, and childhood trauma. One review each examined the relationship between cognitive impairment and age, and aggressive behaviour (Fig. 3). Twelve of the 25 systematic reviews were moderate quality, while two were high quality (Table 5).

Pictorial presentation of factors associated with cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia from reviews included (n = 25). Abbreviations: CIPWS cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia, EF executive function, MMSE mini mental state examination, NC neuro cognition, RPS reasoning and problem solving, SC social cognition, SP speed of processing, ToM theory of mind, WM working memory

As shown in (Fig. 3), the relationship between cognitive impairment in PWS and functionality was examined in seven systematic reviews [50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. One good-quality review [50] concluded that there was no association between cognition and functional outcome. However, the other six reviews [51,52,53,54,55,56] found some association between different domains of cognition and different aspects of functionality. Three of these reviews were poor quality, two moderate quality, and one good-quality review (Fig. 3 and Table 5).

Four reviews [57,58,59,60] examined the relationship between substance use and cognitive impairment in PWS. These reviews reported inconsistent findings. The effect of substance use in cognitive impairment in PWS differed from substance to substance, and from domain to domain (Fig. 3 and Table 5).

Four reviews that examined the association between cognitive impairment in PWS and insight [61,62,63,64] reported mixed findings. One poor-quality review [62] reported inconsistent results, with more studies reporting no association between insight and neurocognition. While the other three reported a significant relationship between poor insight and worse cognitive performance both in neurocognitive and social cognitive domains [61, 63, 64], with stronger relationship in some sub-domains of social cognition (such as theory of mind) [64] (Fig. 3 and Table 5).

With regards to the relationship between cognitive impairment and symptom dimensions, two reviews [65, 66] were included in the umbrella review. These reviews found that cognitive impairment was associated with negative symptoms and disorganized symptoms compared to positive symptoms and depressive symptoms (Fig. 3 and Table 5).

Two reviews examined the relationship between cognition and duration of untreated psychosis [67, 68]. One of these had poor quality and the other one moderate quality. Both concluded that there was no significant association between most neurocognition domains and duration of untreated psychosis, with the exception of general intellectual function, executive function, and trial making test A and B (Fig. 3 and Table 5).

Two reviews examined the relationship between childhood trauma and cognitive impairment in PWS [69, 70]. Both reviews reported significant association between higher rates of childhood trauma and reduced overall cognitive performance; one of these reviews was poor quality and the other one was moderate quality (Fig. 3 and Table 5).

Two reviews [71, 72] were about the relationship between cognitive impairment and treatment. One of these reviews [71] was about the effect of cognitive impairment on response to different forms of treatment. In this review, it was shown that improvement over several evidence-based treatments were linked with baseline measures of cognitive function. The other review was comparing the effect of typical and atypical antipsychotics in treating cognitive impairment in PWS [72]. This review reported that atypical antipsychotics significantly improved cognitive function compared to conventional antipsychotics. This review also concluded that the studies that were included had many methodological limitations that one needs to consider in interpreting the findings (Fig. 3 and Table 5).

One of the reviews we included [73] dealt with the association between cognitive impairment and age. The study concluded that age had direct effect on the score of mini-mental state examination (MMSE); for every four years increase in age of PWS, there was one MMSE point reduction (five times higher than the report in the general population). PWS living in institutions were more impaired compared to those who were living in the community. This was of a poor-quality review (Fig. 3 and Table 5).

The other review included under this section examined the association between cognitive impairment in PWS and aggressive behaviour [74]. This moderate-quality review concluded that cognitive impairment in PWS exerted a significant risk for aggression (Fig. 3 and Table 5).

Discussion

Multiple studies have been published on the magnitude of cognitive impairment in PWS and associated factors. We were able to identify 63 independent reviews, and the majority addressed several neurocognitive domains. Most of the reviews used PubMed and PsycINFO databases to search their included studies. Methodologically, the majority of the studies were of moderate quality.

Of the 63 reviews we identified, some (n = 24) were included in a previous umbrella review of the magnitude of cognitive dysfunction in PWS and people with bipolar disorder [9]. The difference between our review and this previous umbrella review is that, the former only included meta-analysis studies while our review included both meta-analysis and systematic reviews. This previous review was not specific to cognitive impairment in PWS rather it was an umbrella review of cognitive impairment in PWS and people with bipolar disorder. It also focused more on comparing the domains of cognitive impairment in PWS and people with bipolar disorder. The previous review only included meta-analysis of neurocognitive domains, ignoring social cognitive domains, which is considered to be an important predictor of functionality. Finally, the previous review was not comprehensive (searched PubMed only) and the last date of search for the previous umbrella review was on August 10th 2015 (5 years older than ours). These facts make our review more comprehensive compared to it.

Even though the area is extensively researched, none of the included reviews reported the problem from low and middle-income countries (LMICs), separately. Since there are reports which show that cognition can be affected by nutritional status [75], we expect different results in high-income countries compared to that of LMICs. This calls for a separate analysis of the magnitude of cognitive impairment and associated factors based on income level of countries. One of the reasons for the lack of separate analysis may be scarcity of studies from LMICs. Therefore, conducting studies focusing on the magnitude, associated factors, and other interventional studies might be worth considering.

In this umbrella review, we found that PWS have more severe cognitive impairment compared to both healthy controls, people with bipolar disorder, and people with other affective disorders, particularly in the domains of processing speed, verbal memory, and working memory. We also found that the magnitude of cognitive impairment is more or less the same in PWS who were drug free and first episode psychosis, and those who had taken pharmacological treatment. Even though the results were mixed, most of the reviews we included point toward no decline of cognitive impairment in PWS over time. These findings support the hypothesis that cognitive impairment is one of the core symptoms of schizophrenia even at the initial phase of the illness.

This review of reviews showed that cognitive impairment in PWS has significant association with a number of factors, including functionality, substance use, insight, symptom dimensions, history of childhood trauma, older age, and aggressive behaviour. Hence, we recommend future researchers to consider these factors in conducting a study related to factors associated with cognitive impairment in PWS.

This umbrella review is particularly useful for researchers, clinicians, and experts in the area. The implication of this review for research is that it would help researchers in identifying a summary of factors that are potentially associated with cognitive impairment in PWS when planning studies. This study will also have implication for interventional studies that future researchers may design focusing on domains reported to be impaired. Another potential implication of this review is for experts in the area. Experts can refer this review in designing policy and strategies related to cognition in PWS. Clinicians can refer to this review to have a comprehensive understanding of domains of cognition affected and factors associated with cognitive impairment in PWS.

This review has a number of strengths in that we followed PRISMA guideline in conducting and reporting the review. Our search can be considered more comprehensive compared to the one conducted before since we included four databases without restriction on the date of publication, and we also conducted forward and backward searching. Furthermore, we assessed the quality of each of the included reviews, and whenever possible results were presented separately considering the methodological quality of the reviews included.

However, our review is not free from limitations. First, the broad scope of the review made the data analysis difficult, particularly to conduct meta-analysis. The broad scope of the review allowed a wide variety of study outcomes to be included and hence made the review hard to follow. Second, non-English studies were excluded, which might limit the generalizability of the findings. Finally, the grey literature was not searched; however, we used Google Scholar for our forward and backward searching.

Conclusions

This umbrella review highlights cognition as an important factor contributing to functionality and insight in PWS. Considering the presence of 63 different reviews and no review looked for cognitive difference across the economic classification, we encourage reviews that compare cognitive impairment in PWS at different income settings. From this umbrella review, one can conclude that cognitive impairment is a core symptom in PWS and different factors such as functionality, insight, history of childhood trauma, age, and aggressive behavior have significant association with cognitive impairment in this population group.

Data availability

All the data used are made available in the manuscript and supplementary materials.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AMSTAR:

-

A measurement tool to assess methodological quality of systematic review

- DSM:

-

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

- ICD:

-

International classification of diseases

- IQ:

-

Intelligence quotient

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MATRICS:

-

Measurement and treatment research to improve cognition in schizophrenia initiative

- MMSE:

-

Mini-mental state examination

- PANSS:

-

Positive and negative syndrome scale

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- PWS:

-

People with schizophrenia

References

Shahrokh NC, Hales RE, Phillips KA, Yudofsky SC (2011) The language of mental health: a glossary of psychiatric terms. American Psychiatric Publishing

Keefe RS, Eesley CE, Poe MP (2005) Defining a cognitive function decrement in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiat 57(6):688–691

Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK (1998) Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology 12(3):426

Fatouros-Bergman H et al (2014) Meta-analysis of cognitive performance in drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 158(1–3):156–162

American Psychiatric Association, D. S., and American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5, vol 5. American psychiatric association, Washington, DC

Marder SR, Fenton W (2004) Measurement and treatment research to improve cognition in schizophrenia: NIMH MATRICS initiative to support the development of agents for improving cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 72(1):5–9

Carter CS, Barch DM (2007) Cognitive neuroscience-based approaches to measuring and improving treatment effects on cognition in schizophrenia: the CNTRICS initiative. Schizophr Bull 33(5):1131–1137

Nuechterlein KH et al (2004) Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 72(1):29–39

Bortolato B et al (2015) Cognitive dysfunction in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: a systematic review of meta-analyses. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11:3111

World Health Organization (2004) ICD-10: international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision. World Health Organization

Moher D et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097

Aromataris E, Pearson A (2014) The systematic review: an overview. AJN The Am J Nurs 114(3):53–58

Shea BJ et al (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 7:10

Piskulic D et al (2007) Behavioural studies of spatial working memory dysfunction in schizophrenia: a quantitative literature review. Psychiatry Res 150(2):111–121

Aleman A et al (1999) Memory impairment in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 156(9):1358–1366

Lee J, Park S (2005) Working memory impairments in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. J Abnorm Psychol 114(4):599

Pelletier M et al (2005) Cognitive and clinical moderators of recognition memory in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 74(2–3):233–252

Doughty O, Done D (2009) Is semantic memory impaired in schizophrenia? A systematic review and meta-analysis of 91 studies. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 14(6):473–509

Johnson-Selfridge M, Zalewski C (2001) Moderator variables of executive functioning in schizophrenia: meta-analytic findings. Schizophr Bull 27(2):305–316

Dibben C et al (2009) Is executive impairment associated with schizophrenic syndromes? A Meta-Anal Psychological Med 39(3):381–392

Li C-SR (2004) Do schizophrenia patients make more perseverative than non-perseverative errors on the wisconsin card sorting test? A Meta-Anal Study Psychiatry Res 129(2):179–190

Thai ML, Andreassen AK, Bliksted V (2019) A meta-analysis of executive dysfunction in patients with schizophrenia: different degree of impairment in the ecological subdomains of the behavioural assessment of the dysexecutive syndrome. Psychiatry Res 272:230–236

Knowles EE, David AS, Reichenberg A (2010) Processing speed deficits in schizophrenia: reexamining the evidence. Am J Psychiatry 167(7):828–835

Dickinson D, Ramsey ME, Gold JM (2007) Overlooking the obvious: a meta-analytic comparison of digit symbol coding tasks and other cognitive measures in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64(5):532–542

Bokat CE, Goldberg TE (2003) Letter and category fluency in schizophrenic patients: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 64(1):73–78

Henry J, Crawford J (2005) A meta-analytic review of verbal fluency deficits in schizophrenia relative to other neurocognitive deficits. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 10(1):1–33

Savla GN et al (2013) Deficits in domains of social cognition in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Schizophr Bull 39(5):979–992

Javed A, Charles A (2018) The importance of social cognition in improving functional outcomes in schizophrenia. Front Psych 9:157

Trotta A, Murray R, MacCabe J (2015) Do premorbid and post-onset cognitive functioning differ between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 45(2):381–394

Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C (2009) Cognitive functioning in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and affective psychoses: meta-analytic study. Br J Psychiatry 195(6):475–482

Krabbendam L et al (2005) Cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a quantitative review. Schizophr Res 80(2–3):137–149

Stefanopoulou E et al (2009) Cognitive functioning in patients with affective disorders and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 21(4):336–356

Kuswanto C et al (2016) Shared and divergent neurocognitive impairments in adult patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: whither the evidence? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 61:66–89

Schaefer J et al (2013) The global cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: consistent over decades and around the world. Schizophr Res 150(1):42–50

Fioravanti M, Bianchi V, Cinti ME (2012) Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: an updated metanalysis of the scientific evidence. BMC Psychiatry 12(1):64

Fioravanti M et al (2005) A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Neuropsychol Rev 15(2):73–95

Mesholam-Gately RI et al (2009) Neurocognition in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology 23(3):315

Rajji T, Ismail Z, Mulsant B (2009) Age at onset and cognition in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 195(4):286–293

Zhang H et al (2019) Meta-analysis of cognitive function in Chinese first-episode schizophrenia: MATRICS consensus cognitive battery (MCCB) profile of impairment. Gen Psychiatry 32(3):e100043

Aas M et al (2014) A systematic review of cognitive function in first-episode psychosis, including a discussion on childhood trauma, stress, and inflammation. Front Psych 4:182

Bora E, Pantelis C (2015) Meta-analysis of cognitive impairment in first-episode bipolar disorder: comparison with first-episode schizophrenia and healthy controls. Schizophr Bull 41(5):1095–1104

Thibaudeau E, Achim AM, Parent C, Turcotte M, Cellard C (2019) A meta-analysis of the associations between theory of mind and neurocognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 216:118–128

Pickup GJ (2008) Relationship between theory of mind and executive function in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Psychopathology 41(4):206–213

Shah JN et al (2012) Is there evidence for late cognitive decline in chronic schizophrenia? Psychiatr Q 83(2):127–144

Irani F et al (2010) Neuropsychological performance in older patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Schizophr Bull 37(6):1318–1326

Bozikas VP, Andreou C (2011) Longitudinal studies of cognition in first episode psychosis: a systematic review of the literature. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 45(2):93–108

Szöke A et al (2008) Longitudinal studies of cognition in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 192(4):248–257

Woodberry KA, Giuliano AJ, Seidman LJ (2008) Premorbid IQ in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Am J Psychiatry 165(5):579–587

Khandaker GM et al (2011) A quantitative meta-analysis of population-based studies of premorbid intelligence and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 132(2–3):220–227

Allott K et al (2011) Cognition at illness onset as a predictor of later functional outcome in early psychosis: systematic review and methodological critique. Schizophr Res 125(2–3):221–235

Christensen TØ (2007) The influence of neurocognitive dysfunctions on work capacity in schizophrenia patients: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 11(2):89–101

Couture SM, Penn DL, Roberts DL (2006) The functional significance of social cognition in schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Bull 32(suppl_1):S44–S63

Fett A-KJ et al (2011) The relationship between neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35(3):573–588

Halverson TF et al (2019) Pathways to functional outcomes in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: meta-analysis of social cognitive and neurocognitive predictors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 105:212–219

Schmidt SJ, Mueller DR, Roder V (2011) Social cognition as a mediator variable between neurocognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: empirical review and new results by structural equation modeling. Schizophr Bull 37(suppl_2):S41–S54

Rajji TK, Miranda D, Mulsant BH (2014) Cognition, function, and disability in patients with schizophrenia: a review of longitudinal studies. The Canadian J Psychiatry 59(1):13–17

Donoghue K, Doody GA (2012) Effect of illegal substance use on cognitive function in individuals with a psychotic disorder: a review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychology 26(6):785–801

Yücel M et al (2010) The impact of cannabis use on cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of existing findings and new data in a first-episode sample. Schizophr Bull 38(2):316–330

Coulston CM, Perdices M, Tennant CC (2007) The neuropsychology of cannabis and other substance use in schizophrenia: review of the literature and critical evaluation of methodological issues. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 41(11):869–884

Potvin S et al (2008) Contradictory cognitive capacities among substance-abusing patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 100(1–3):242–251

Agrawal N et al (2003) Insight in psychosis and neuropsychological function: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 1(60):121

Cooke M et al (2005) Disease, deficit or denial? Models of poor insight in psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 112(1):4–17

Nair A et al (2014) Relationship between cognition, clinical and cognitive insight in psychotic disorders: a review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 152(1):191–200

Subotnik KL, Ventura J, Hellemann GS, Zito MF, Agee ER, Nuechterlein KH (2020) Relationship of poor insight to neurocognition, social cognition, and psychiatric symptoms in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 220:164–171

Dominguez Mde G et al (2009) Are psychotic psychopathology and neurocognition orthogonal? A systematic review of their associations. Psychol Bull 135(1):157–171

Nieuwenstein MR, Aleman A, de Haan EH (2001) Relationship between symptom dimensions and neurocognitive functioning in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of WCST and CPT studies. J Psychiatr Res 35(2):119–125

Allott K et al (2018) Duration of untreated psychosis and neurocognitive functioning in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 48(10):1592–1607

Bora E et al (2018) Duration of untreated psychosis and neurocognition in first-episode psychosis: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 193:3–10

Dauvermann MR, Donohoe G (2019) The role of childhood trauma in cognitive performance in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder–A systematic review. Schizophr Res: Cognit 16:1–11

Vargas T et al (2019) Childhood trauma and neurocognition in adults with psychotic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull 45(6):1195–1208

Kurtz MM (2011) Neurocognition as a predictor of response to evidence-based psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia: what is the state of the evidence? Clin Psychol Rev 31(4):663–672

Keefe RS et al (1999) The effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs on neurocognitive impairment in schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull 25(2):201–222

Maltais J-R et al (2015) Correlation between age and MMSE in schizophrenia. Int Psychogeriatr 27(11):1769–1775

Reinharth J et al (2014) Cognitive predictors of violence in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Schizophr Res: Cognit 1(2):101–111

Kerac M, Postels DG, Mallewa M, Jalloh AA, Voskuijl WP, Groce N, Gladstone M, Molyneux E (2014) The interaction of malnutrition and neurologic disability in Africa. In: Seminars in pediatric neurology, vol 21, no 1. WB Saunders, pp 42–49

Bowie CR, Harvey PD (2005) Cognition in schizophrenia: impairments, determinants, and functional importance. Psychiatr Clin North Am 28(3):613–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2005.05.004

Braff DL (1993) Information processing and attention dysfunctions in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 19(2):233–259

Kayman DJ, Goldstein MF (2012) Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Curr Transl Geriatr Gerontol Rep 1(1):45–52

Acknowledgements

Our special thanks goes to the staff of the Department of Psychiatry, Addis Ababa University, who provided valuable comments on different occasions. We also would like to thank Debre Berhan University for sponsoring the primary investigator to conduct this review. Finally, we would like to thank the African Mental Health Research Initiative (AMARI), because this work was supported by the DELTAS Africa Initiative [DEL-15-01] through the first author (YG). The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)’s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust [DEL-15-01] and the UK government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of AAS, NEPAD Agency, WellcomeTrust or the UK government.

Funding

This work was supported by the DELTAS Africa Initiative [DEL-15-01] through the first author (YG). The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)’s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust [DEL-15-01] and the UK government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of AAS, NEPAD Agency, Wellcome Trust or the UK government. The funder has no role in the interpretation of findings and decision for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YG, AA, KH, and MC: conceived and designed the study. YG and AM: involved in screening, extraction, quality assessment and drafting the manuscript. All the authors have read the manuscript and have given their final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gebreegziabhere, Y., Habatmu, K., Mihretu, A. et al. Cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia: an umbrella review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 272, 1139–1155 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01416-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01416-6