Abstract

Objectives

Head and neck cancers (HNCs) represent a significant global health concern due to high morbidity and mortality rates. Despite therapeutic advances, the prognosis for advanced or recurrent cases remains challenging. Nivolumab obtained approval for recurrent or metastatic HNC based on the Phase III CheckMate 141 trial. This study aimed to evaluate the real-world outcomes of nivolumab in patients with non-nasopharyngeal HNC.

Design

In this multicenter retrospective study, we analyzed 124 patients with recurrent or metastatic non-nasopharyngeal HNC who received nivolumab in the second-line setting and beyond. Data were collected from 20 different cancer centers across Turkey. The effectiveness and safety of the treatment and survival outcomes were evaluated.

Results

Nivolumab exhibited favorable clinical responses, yielding an objective response rate of 29.9% and a disease control rate of 55.7%. Safety assessments revealed a generally well-tolerated profile, with no instances of treatment discontinuation or mortality due to side effects. Survival analysis disclosed a median overall survival (OS) of 11.8 (95% CI 8.4–15.2) months. Multivariate analysis revealed that ECOG-PS ≥ 1 (HR: 1.64, p = 0.045), laryngeal location (HR: 0.531, p = 0.024), and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio > 3.5 (HR: 1.97, p = 0.007) were independent predictors of OS.

Conclusions

Nivolumab is an effective and safe treatment option for patients with recurrent or metastatic non-nasopharyngeal HNC in real-world settings. Further studies are needed on factors affecting response to treatment and survival outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) is the sixth most prevalent cancer worldwide and the eighth most common cause of cancer-related death [1,2,3]. It encompasses a diverse group of malignancies arising from the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, nasal cavity, or paranasal sinuses. Despite therapeutic advances, including surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy, the prognosis for patients with advanced or recurrent disease remains challenging [4,5,6]. Twenty to forty percent of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) will experience local/regional recurrence or metastasis following primary treatment [5, 7]. Therefore, there is a critical need for novel therapeutic approaches to improve outcomes in this population.

Recently, immunotherapy has emerged as a promising modality in various malignancies, including HNC [8]. Nivolumab, a programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitor, has demonstrated significant clinical activity and improved survival outcomes in patients with advanced HNSCC [8, 9]. These studies have highlighted the potential of nivolumab to improve survival outcomes and provide durable responses in patients with advanced or recurrent HNC. However, the real-world effectiveness and safety profile of nivolumab in a multicenter setting, specifically in the second-line and subsequent treatment, remain to be fully elucidated [10,11,12].

In this study, we aimed to present the results of a multicenter retrospective analysis focusing on Turkish patients with HNC who received nivolumab as a second-line or subsequent therapy. By assessing real-world data from multiple centers, we assessed the clinical effectiveness and safety profile of nivolumab and survival outcomes in this population.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

The study included ≥ 18-years-old patients with histologically confirmed non-nasopharyngeal recurrent or metastatic, platinum-refractory HNC from 20 different cancer centers across Turkey. The study encompassed patients who had previously received at least one course of systemic therapy in the metastatic context or those who had experienced relapse following local treatments. The eligibility criterion was receiving at least 3 cycles of nivolumab as second or next-line therapy. The demographic characteristics of the patients, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-performance status (ECOG-PS) and neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) at the start of nivolumab therapy, primary tumor locations, histological diagnosis, p16 or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) positivity, and previous treatments were examined retrospectively. Nivolumab was administered as an intravenous perfusion over 30 min, at intervals of 14 or 21 days. Patients were radiologically evaluated every two to four cycles by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. The Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) was employed to assess the treatment response. History and physical examination and blood work including hemoglobin, white blood cells, platelets, liver function tests, creatinine, thyroid stimulating hormone, and cortisol were done at each participating center shortly before each cycle. Toxicity was categorized using the Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE, version 4.03). This study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and was approved by the respective institutional review boards of all participating centers.

Study outcomes

The primary outcomes of the study were the efficacy and safety of nivolumab. Efficacy endpoints included overall response rate (ORR, sum of complete and partial response rates) and disease control rate (DCR, sum of complete and partial response and stable disease rates). Safety assessments focused on the incidence and severity of adverse events. The secondary objective of the study was to reveal survival outcomes and prognostic factors.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as frequency (percent), mean ± standard deviation (SD), or median (minimum–maximum). The χ2 and Exact tests were used to compare the proportions in different categorical groups. The time from the onset of nivolumab to death from any cause was defined as overall survival (OS); to radiological progression or death was defined as progression-free survival (PFS). Survival estimates were calculated with the Kaplan–Meier method. The impact of prognostic variables on OS was investigated through univariate Cox regression analysis. Multivariate analysis was conducted to examine the independent effects of factors that demonstrated significance in univariate analyses and had complete data for all patients. A 5% type-I error level (p < 0.05) was used to infer statistical significance.

Results

Patient characteristics

The mean age of 124 patients (73.4% men) was 59.4 ± 13.7 (range, 20–88) years, and 66 (53.2%) patients were over 60 years of age. Smoking history was present in 76 of the 98 patients whose information was available. ECOG-PS was 0 in 63 (50.8%) patients, 1 in 46 (37.1%) patients, and 2 in 15 (12.1%) patients. The most common primary tumor site was the larynx (34.7%), and the others were the oral cavity (29%), hypopharynx (18.5%), oropharynx (8.1%), paranasal sinus (5.6%), and others (4%), respectively. The histological subtype was squamous cell carcinoma in 97.6% of the patients. Among the examined patients, the p16 positivity rate was 23.6% (13/55), and the PD-L1 positivity rate was 51.5% (17/33). Distant metastasis sites were lung (46%), bone (25.8%), soft tissue (21.8%), liver (16.1%), brain (3.2%) and other organs (8.1%), respectively. Treatments before nivolumab included chemoradiation (70.2%), surgery (50%), adjuvant (38.7%), and induction (24.2%) therapies. The number of treatment lines before nivolumab was 1 in 54 (43.5%) patients, 2 in 35 (28.2%) patients, and ≥ 3 in 35 (28.2%) patients. The median dose of nivolumab was 200 (100–240) mg, and the median number of cycles was 6 (3–80). The cycle interval was 14 days and 21 days in 104 (83.9%) and 20 (16.1%) patients, respectively. Concurrent radiotherapy with nivolumab was administered to 18 (14.5%) patients. At the beginning of nivolumab treatment, the median NLR was 3.6 (0.8–19.2) (Table 1).

Efficacy and safety

The best responses to nivolumab treatment were evaluated in the study. Complete and partial responses were obtained in 8 (6.5%) and 29 (23.4%) patients, respectively. The disease remained stable in 32 (25.8%) patients, but progressed in 55 (44.4%) patients. Herewith, the ORR was 29.9% and DCR was 55.7%. Neither ORR nor DCR was associated with PD-L1 positivity (p = 0.335 and 0.393, respectively, Fig. 1). Nivolumab was generally well tolerated. There was no treatment discontinuation or mortality due to side effects. Grade 1–2 side effects were encountered in a total of 10 (8.1%) patients (5 hypothyroidism, 2 hypophysitis, 1 pneumonitis, 1 hepatotoxicity, and 1 malaise).

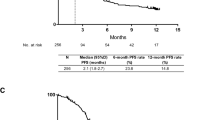

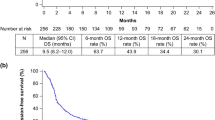

Survival analysis

During a median follow-up period of 7.5 (0.5–66.1) months, the disease progressed in 89 patients and 70 patients died. The median OS was 11.8 (95% CI 8.4–15.2) months, and the median PFS was 3.8 (95% CI 3.1–4.5) months. The 1-year OS and PFS rates were 49.4% (95%CI 39.6–59.2) and 27.4% (95%CI 18.8–36), respectively (Fig. 2). In univariate analyses, age > 60, male gender, smoking, PD-L1 positivity, metastasis sites, previous treatments, number of previous treatment lines, nivolumab dose, cycle interval, and concurrent chemotherapy were not found to be associated with OS (Table 2). ECOG-PS ≥ 1 (p = 0.023) and NLR > 3.5 (p = 0.006) negatively affected OS, while laryngeal location (p = 0.006) and p16 positivity (p = 0.04) were associated with increased OS. The independent effects of factors found to be significant in univariate OS analyzes were examined by multivariate model. P16 positivity was excluded due to an insufficient number of data (55 of 124 patients). Finally, multivariate analysis revealed that ECOG-PS ≥ 1 (HR: 1.64, p = 0.045), laryngeal location of the primary tumor (HR: 0.53, p = 0.024), and NLR > 3.5 (HR: 1.97, p = 0.007) were independent predictors of OS (Fig. 3 a, b, c). The impact of p16 positivity on OS was investigated using a distinct model comprising 55 patients who underwent p16 testing (Table 3). The analysis unveiled that p16 positivity significantly enhanced overall survival, irrespective of ECOG-PS, primary tumor location, and NLR (HR: 0.39, %95CI 0.16–0.98, p = 0.045, Fig. 3 d).

Discussion

In this study, we shared our clinical experience with nivolumab treatment in patients with recurrent or metastatic non-nasopharyngeal HNC in Turkey. Although there are studies in the literature involving patients with nasopharyngeal cancer and HNC receiving immunotherapy [13,14,15], this study focused exclusively on non-nasopharyngeal cancer due to its distinct differences in terms of epidemiology, histology, natural progression, and response to treatment when compared to other HNCs.

Our cohort comprised 124 patients, with a notable male predominance of 73.4%, consistent with the higher incidence of HNC in males [16]. The mean age of 59.4 years, with 53.2% of patients over 60 years old, reflects the wide age distribution of HNC diagnoses, emphasizing the importance of tailored treatments across different age groups [17]. Evaluating the efficacy of nivolumab in this cohort, we observed encouraging responses, with complete and partial responses achieved in 6.5% and 23.4% of patients, respectively. Stable disease was noted in 25.8% of patients. As a result, the ORR to nivolumab treatment reached 29.9%, while the DCR was 55.7%, underscoring the potential clinical benefit of nivolumab in recurrent or metastatic HNC. These results were notably consistent with the Checkmate-141 trial [18]. Furthermore, the effectiveness and safety of nivolumab in this context have been corroborated by various retrospective studies conducted with diverse real-world data, demonstrating an ORR ranging from 13.5% to 29.6% and a median PFS spanning from 3.7 to 6.4 months [19,20,21]. The longer PFS observed in our study may be attributed to the less frequent performance of response evaluations in patients, as opposed to the rigorous monitoring in clinical trials.

Survival analysis provided valuable prognostic insights, with a median OS of 11.8 months. The 1-year OS and PFS rates were 49.4% and 27.4%, respectively, highlighting the need for more effective treatments in recurrent or metastatic HNC. In a Japanese study involving patients with recurrent or metastatic HNSCC, it was observed to be relatively high, with a median OS of 74.1 weeks [22]. In a different study, the median OS was found to be 9.2 months [14]. In the Korean study, the median OS was found to be 11.8 months [23], which is longer than the Checkmate 141 study (7.5 months). The variation in reported survival rates between studies conducted in Asian and Western societies highlights the potential differences in disease progression between these regions. Nevertheless, there is a paucity of data in the literature regarding patients receiving nivolumab for HNC in the Middle Eastern population. However, as deduced from our study and the literature, nivolumab offers a superior survival benefit compared to chemotherapy in patients with recurrent or metastatic HNC. Based on the data in this study and the existing literature, it is apparent that PFS is not a reliable indicator in immunotherapy studies, whereas OS holds greater significance.

Nivolumab demonstrated an overall favorable safety profile in our study. Notably, there were no instances of treatment discontinuation or mortality attributed to side effects. Grade 1–2 side effects were encountered in a total of 8.1% of patients, comprising various manageable adverse events. In the Checkmate 141 clinical trial, grade 3 or 4 adverse events were reported in 13.1% of the nivolumab group. Two treatment-related deaths were reported in the nivolumab group, while treatment discontinuation due to severe side effects has not been documented [18]. The lower reported side effect profile in our study may be attributed to potential underdiagnosis in retrospective real-life data, as opposed to controlled clinical trials. However, in our study, no instances of treatment discontinuation or treatment-related deaths resulting from serious immune-related side effects were observed. These data indicate that nivolumab is a safe option for patients with HNC.

Univariate analyses identified factors associated with OS, including ECOG-PS ≥ 1 and NLR > 3.5, both negatively affecting OS. Conversely, laryngeal location and p16 positivity were associated with increased OS. Multivariate analysis confirmed ECOG-PS ≥ 1, laryngeal location, and NLR > 3.5 as independent predictors of OS in the entire cohort. Furthermore, in a subgroup analysis of 55 patients who underwent p16 testing, p16 positivity emerged as the sole independent factor. The Checkmate-141 study demonstrated a more significant survival benefit in the subgroup with PD-L1 expression ≥ 1 (HR: 0.55, 95% CI 0.36–0.83) compared to the PD-L1 < 1 subgroup (HR: 0.89, 95% CI 0.54–1.45) [18]. In our cohort, PD-L1 status was assessed in a limited subset of 33 patients, revealing positivity in 51.5% (17/33) of cases. Univariate analysis indicated that PD-L1 positivity did not have an impact on survival. Given the incomplete patient examination and the small sample size, different results might have been obtained in a clinical trial. The significance of PD-L1 expression, particularly at the 1% threshold, remains debated. Although higher PD-L1 levels were linked to improved survival in the KEYNOTE-012 study, later research suggests that even patients with lower PD-L1 expression levels may benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors [24]. Therefore, further studies involving a larger patient population are necessary to validate these findings. On the other hand, p16 positivity was identified as a factor positively influencing survival. Consistently, in Checkmate 141 study, the median OS among patients with p16-positive tumors was 9.1 months, whereas it was 7.5 months in the nivolumab group for patients with p16-negative tumors (HR: 0.73, 95% CI 0.42–1.25, p = 0.55) [18]. It is possible that the dynamics of the NLR, reflecting the antitumor immune response during immunotherapy, are directly linked to peripheral treatments and subsequent positive clinical outcomes [25]. NLR serves as a broad-spectrum indicator and can act as a surrogate for the balance between tumor-mediated therapy and antitumor immunity, influencing both cancer progression and overall systemic therapy efficacy [26]. High pretreatment NLR has been correlated with adverse outcomes and may also be associated with inadequate response to immunotherapy [26,27,28]. Similarly, in our study, an NLR score > 3.5 was identified as one of the factors significantly negatively impacting survival (p = 0.007).

Our study shares several limitations common to retrospective studies. It employed an observational design, lacking a control group. Given that data were collected by individual physicians during routine clinical practice, patient medical records may not consistently offer complete, comparable information and may include measurement errors. Clinical response assessment relied on physician evaluation, which was not standardized within this real-world study. Additionally, to ensure a sufficient sample size, we included healthcare centers with substantial HNC patient populations, which might introduce selection bias into our study population.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our multicenter retrospective study in Turkish patients with recurrent or metastatic non-nasopharyngeal HNC receiving nivolumab treatment provides valuable real-world insights. The study underlines the potential of nivolumab as a therapeutic option and the importance of personalized treatment approaches. Despite study limitations, including its retrospective nature and sample size, our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence in support of nivolumab in recurrent or metastatic HNC. Further research endeavors are warranted to validate these observations and advance the care and outcomes of patients with HNC.

Availability of data

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DCR:

-

Disease control rate

- ECOG-PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-performance status

- HNC:

-

Head and neck cancer

- HNSCC:

-

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio

- ORR:

-

Overall response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed death-ligand 1

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68(6):394–424

Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM et al (2017) Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol 3(4):524–548

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2018) Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 68(1):7–30

Chow LQM (2020) Head and Neck Cancer. N Engl J Med 382(1):60–72

Vermorken JB, Specenier P (2010) Optimal treatment for recurrent/metastatic head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol 21(Suppl 7):vii252–vii261

Marur S, Forastiere AA (2008) Head and neck cancer: changing epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 83(4):489–501

Pisani P, Airoldi M, Allais A et al (2020) Metastatic disease in head & neck oncology. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 40(Suppl. 1):S1-s86

Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Fayette J et al (2016) Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 375(19):1856–1867

Cohen EEW, Bell RB, Bifulco CB et al (2019) The Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer consensus statement on immunotherapy for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (HNSCC). J Immunother Cancer 7(1):184

Yasumatsu R, Shimizu Y, Hanai N et al (2022) Outcomes of long-term nivolumab and subsequent chemotherapy in Japanese patients with head and neck cancer: 2-year follow-up from a multicenter real-world study. Int J Clin Oncol 27(1):95–104

Vasiliadou I, Breik O, Baker H et al (2021) Safety and treatment outcomes of nivolumab for the treatment of recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: retrospective multicenter cohort study. Cancers (Basel) 13(6):1413

Matsuki T, Okamoto I, Fushimi C et al (2020) Real-world, long-term outcomes of nivolumab therapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and impact of the magnitude of best overall response: a retrospective multicenter study of 88 patients. Cancers (Basel) 12(11):3427

Wagner SM, Magnes T, Melchardt T et al (2023) Real-world data of palliative first-line checkpoint inhibitor therapy for head and neck cancer. Anticancer Res 43(3):1273–1282

Gogate A, Bennett B, Poonja Z et al (2023) Phase 4 multinational multicenter retrospective and prospective real-world study of nivolumab in recurrent and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancers (Basel) 15(14):3552

Kariya S, Shimizu Y, Hanai N et al (2021) Effectiveness of nivolumab affected by prior cetuximab use and neck dissection in Japanese patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer: results from a retrospective observational study in a real-world setting. Int J Clin Oncol 26(6):1049–1056

Serindere G, Bolgul B, Gursoy D, Hakverdi S, Savas N (2019) Comparison of head and neck cancer distribution in Turkish and Syrian populations. Iran J Public Health 48(10):1810–1816

Guo K, Xiao W, Chen X, Zhao Z, Lin Y, Chen G (2021) Epidemiological trends of head and neck cancer: a population-based study. Biomed Res Int 2021:1738932

Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Fayette J et al (2018) Nivolumab vs investigator’s choice in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: 2-year long-term survival update of CheckMate 141 with analyses by tumor PD-L1 expression. Oral Oncol 81:45–51

Okamoto I, Sato H, Kondo T et al (2019) Efficacy and safety of nivolumab in 100 patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer - a retrospective multicentre study. Acta Otolaryngol 139(10):918–925

Matsuo M, Yasumatsu R, Masuda M et al (2020) Relationship between immune-related adverse events and the long-term outcomes in recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab. Oral Oncol 101:104525

Hori R, Shinohara S, Kojima T et al (2019) Real-world outcomes and prognostic factors in patients receiving nivolumab therapy for recurrent or metastatic head and neck carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 11(9):1317

Otsuki S, Hori R, Shinohara S et al (2022) Real-world 2-year long-term outcomes and prognostic factors in patients receiving nivolumab therapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Auris Nasus Larynx 49(5):834–844

Kim H, Kwon M, Kim B et al (2020) Clinical outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer: real-world data in Korea. BMC Cancer 20(1):727

Vallianou NG, Evangelopoulos A, Kounatidis D et al (2023) Immunotherapy in head and neck cancer: where do we stand? Curr Oncol Rep 25(8):897–912

Hwang M, Canzoniero JV, Rosner S et al (2022) Peripheral blood immune cell dynamics reflect antitumor immune responses and predict clinical response to immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 10(6):e004688

Valero C, Lee M, Hoen D et al (2021) Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mutational burden as biomarkers of tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Commun 12(1):729

Cao D, Xu H, Xu X, Guo T, Ge W (2018) A reliable and feasible way to predict the benefits of Nivolumab in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of 14 retrospective studies. Oncoimmunology 7(11):e1507262

Nakaya A, Kurata T, Yoshioka H et al (2018) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as an early marker of outcomes in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. Int J Clin Oncol 23(4):634–640

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK). The authors received no financial support for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights

All procedures in this study involving human participants followed the institutional research committee’s ethical standards, as well as the principles outlined in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akyildiz, A., Guven, D.C., Koksal, B. et al. Real-world evaluation of nivolumab in patients with non-nasopharyngeal recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer: a retrospective multi-center study by the Turkish Oncology Group (TOG). Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-024-08744-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-024-08744-4